Those who argue that lame-duck presidents should not nominate justices to the Supreme Court have forgotten or ignored the most consequential appointment in the Court's -- and the nation's -- history: President John Adams's 1801 appointment of John Marshall as the nation's fourth Chief Justice.

The post John Marshall, the lame-duck appointment to Chief Justice appeared first on OUPblog.

New Bench …

Three-judge SC bench to hear Yakub Memons plea today – Livemint

The curative writ petition filed by the 1993 Bombay blasts convict Yakub Memon will now be considered by a three-judge bench of the Supreme Court on Wednesday.

The decision was taken by the chief justice of India (CJI) H.L.

Dattu after a two-judge bench of justices Anil R. Dave and Kurian Joseph gave a split verdict on Tuesday.

Senior counsel Raju Ramachandran, appearing on Memon’s behalf, mentioned the matter before a five-judge bench headed by Dattu.

“I will constitute a bench,” Dattu said when the matter was presented before him but he refused to stay the execution.

Dave said the matter should be heard immediately, preferably on Wednesday, given the urgency of the issue. Read more…

The post New Bench appeared first on Monica Gupta.

By Dennis Baron

The Supreme Court is using dictionaries to interpret the Constitution. Both conservative justices, who believe the Constitution means today exactly what the Framers meant in the 18th century, and liberal ones, who see the Constitution as a living, breathing document changing with the times, are turning to dictionaries more than ever to interpret our laws: a new report shows that the justices have looked up almost 300 words or phrases in the past decade. Earlier this month, according to the New York Times, Chief Justice Roberts consulted five dictionaries for a single case.

Even though judicial dictionary look-ups are on the rise, the Court has never commented on how or why dictionary definitions play a role in Constitutional decisions. That’s further complicated by the fact that dictionaries aren’t designed to be legal authorities, or even authorities on language, though many people, including the justices of the Supreme Court, think of them that way. What dictionaries are, instead, are records of how some speakers and writers have used words. Dictionaries don’t include all the words there are, and except for an occasional usage note, they don’t tell us what to do with the words they do record. Although we often say, “The dictionary says…,” there are many dictionaries, and they don’t always agree.

As for the justices, they aren’t just looking up technical terms like battery, lien, and prima facie, words which any lawyer should know by heart. They’re also checking ordinary words like also, if, now, and even ambiguous. One of the words Chief Justice Roberts looked up last week in a patent case was of. These are words whose meanings even the average person might consider beyond dispute.

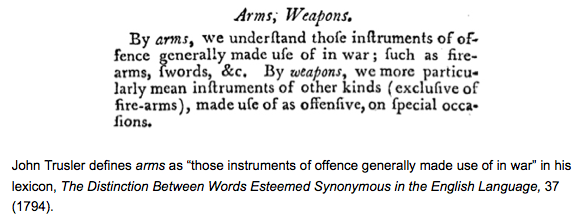

Sometimes dictionary definitions inform landmark decisions. In Washington, DC, v. Heller (2008), the case in which the high Court decided the meaning of the Second Amendment right to keep and bear arms, both Justice Scalia and Justice Stevens checked the dictionary definition of arms. Along with the dictionaries of Samuel Johnson and Noah Webster, Justice Scalia cited Timothy Cunningham’s New and Complete Law Dictionary (1771), where arms is defined as “any thing that a man wears for his defence, or takes into his hands, or useth in wrath to cast at or strike another” (variations on this definition occur in English legal texts going back to the 16th century). And Justice Stevens cited both Samuel Johnson’s definition of arms as “weapons of offence, or armour of defence” (1755) and John Trusler’s “by arms, we understand those instruments of offence generally made use of in war; such as firearms, swords, &c.” (1794).

The much less publicized case of Barnhart v. Peabody Coal Co. (2003) turned in part on the meaning of a single word, shall. In this case the justices all agreed that the word shall in one particular section of the federal Coal Act functions as a command. What they disagreed about was just how much latitude the use of shall permits.

In Peabody Coal the Court’s majority decided that s