Another book for Black History Month. Title: the First Step, How One Girl Put Segregation on Trial Written by: Susan E. Goodman illustrated by: E. B. Lewis Published by: Bloomsbury, 2015 Genre: historical fiction, 40 pages Themes: segregation, discrimination in education, Boston, Sarah C Roberts, African Americans Ages: 7-11 Opening: Sarah Roberts was four … Continue reading

Add a CommentViewing: Blog Posts Tagged with: 19th century, Most Recent at Top [Help]

Results 1 - 25 of 27

Blog: Miss Marple's Musings (Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags: Historical fiction, Boston, 19th century, Segregation, E B White, African Americans, Perfect Picture Book Friday, PPBF, discrimination in education, How One Girl Put Segregation on Trial, Roberts v Boston, Sarah C Roberts, Susa E Goodman, the First Step, Add a tag

Blog: OUPblog (Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags: Arts & Humanities, 19th Century Novelists, Anthony Trollope Between Britain and Ireland, John McCourt, Writing The Frontier, Books, Literature, Novels, ireland, Irish Literature, 19th century, anthony trollope, english literature, *Featured, 19th century literature, Trollope, Add a tag

Nathaniel Hawthorne famously commented that Anthony Trollope’s quintessentially English novels were written on the "strength of beef and through the inspiration of ale … these books are just as English as a beef-steak.” In like mode, Irish critic Stephen Gwynn said Trollope was “as English as John Bull.” But unlike the other great Victorian English writers, Trollope became Trollope by leaving his homeland and making his life across the water in Ireland, and achieving there his first successes there in both his post office and his literary careers.

The post Anthony Trollope: an Irish writer appeared first on OUPblog.

Blog: OUPblog (Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags: Clive Dewey, Indus River, Limits of Western Technological Superiority in South Asia, Steamboats, Steamboats on the Indus, steamships, Books, History, Technology, India, Asia, transportation, 19th century, *Featured, Punjab, british empire, Add a tag

Congratulations on your new posting in the Punjab. Rather than riding eight-hours-a-day on horseback, suffering motion-sickness on a camel’s heaving back, or breaking your back sitting on hard wooden boards in a mail-cart, you’ll be travelling on the Bombay Government Flotilla, one of four flotillas that carry thousands of Europeans and Indians up and down the Indus.

While you may question the expenditure of a government flotilla, we assure you it’s a lot simpler than loading a squadron onto a small fleet of country boats, with indifferent crews, in varying states of repair, which might never reach their destinations. On board we’ll keeping the regiment together arriving as it started out — in one piece and maintaining proper discipline in transit.

So what can you expect on this exciting journey?

1. Expect sun and swelter. Everything you touch will be red hot. You won’t be able to go below in the daytime, but the thin awnings on deck will do little to relieve you in the 115 degree heat. Many soldiers ask whether they should sleep with a berth next to a furnace or choose a wall of heat on deck. With dry winds that come down from the ‘burnt-up hills’, laden with fine sand, everything and everyone will be covered in a layer of fine grey grit. And don’t forget the sand-flies — they bite hard.

2. Expect an uproarious time. Remember that you’re travelling on white man’s mastery of nature, so don’t expect to be the most important thing afloat. Your accommodation will be conveniently crushed between the machinery of furnaces, boilers, pistons, transmission, and paddle-wheels. Passengers trapped in close proximity to the machinery enthuse about the clamour of pistons ‘working up to four or five hundred horse-power’, the splash of paddle-wheels beating the river-water into foam, and the deafening hurricanes when engineers blow off the boiler’s steam ‘half-a-dozen times a day’. And if you’re lucky enough to have the wind blowing in your direction, look forward to being choked by the smoke, singed by the sparks, and splattered by smuts from the funnels.

3. Expect to get intimate with your fellow passengers. When moving to a theatre of war, you’ll be squashed together on the decks ‘like pigs at a market in a pen at night’. Your comrades may jostle to get enough space to lie down; the top of a hatch is a prize reserved for the best bare-knuckle fighter. Never mind about a restless colleague, you’ll be packed so tight in the gaps between the baggage, that once you’re settled down it’ll be impossible to move until the morning.

4. Expect cool nights with fresh dew. As you lay on deck with only a thin cotton awning over your head, gather round the funnel to get a little warmth. Be sure to hang on to your guttery [very thin duvet stuffed with raw cotton] as there will be no great-coats among the soldiers. Not to worry, the women and children suffer most.

5. Expect to be out of your element and out of sorts. Feeling exposed? Living on the open decks for weeks on end in the winter will reduce your resistance to all common Indian diseases. Should you be lucky enough to get an attack fever and dysentery, you’ll lay stretched upon the hard planking without anything under or over you. The sepoys’ conditions, as one would expect, are the best of all. It will be impossible to cross the deck without walking on sick and dying invalids. If they die in the night, they will be ‘instantly thrown overboard’. And after the steamer arrives in the delta, the survivors are off-loaded into sea-going ships destined for Bombay.

6. Expect unbelievable meals. Passengers praise our ‘coarse and unpalatable’ food. Everyone from the boat captains to the cooks have their special arrangements with prices too high for poorer travellers and meals ‘so indifferent’ that passengers who had paid for them refuse to eat them. Even the water is undrinkable! Perhaps your whole regiment will be reduced to foraging in the villages along the banks. Sheep and cows can be bought for a few rupees; Muslim butchers slaughter them; and you can enjoy broiling away till midnight.

7. Expect a tranquil environment. It takes a month or more to get up the whole navigable length of the Indus and they’ll be nothing to see on long stretches of the rivers, except ‘a vast dreary expanse’ of desert stretching out to the horizon, or an endless belt of tamarisk trees running along the low, muddy banks. Many villages are miles from the river to escape the floods, so it’s possible to sail all day without seeing another human being. Throughout the journey you’ll receive small stimulations from a native boat spreading its sail to taking pot shots at the largest living creatures to hand. Never mind the cost of the cartridges: simply steal rounds from the pouches of sick sepoys.

8. Expect a friendly drink or two. Fed up with watching the ‘dreary wilderness’ floating slowly past? Drink yourself stupid. As a hundred soldiers boarded the Meanee en route to the siege of Multan, one of them – delirious from drink – ‘slipped from the men who led him and fell overboard’, a second died of delirium tremens during the voyage, and a third ‘was expected to do so’. En route they ‘lost three or four in the river from drowning’. Worried the military authorities will restrict the sale of alcohol on the boats? Buy country liquor from the villagers – it has roughly the same side-effects.

9. Expect genuine thrills. The most intense excitement on a voyage on the Indus is the occasional shipwreck. Test your phlegm, and proof of national identity. Charles Stewart dismissed the danger of drowning with the utmost nonchalance on his sinking vessel. The really serious inconvenience was the interruption to his meals. React with that much aplomb, and we’ll know you’re British.

10. Expect to see people working together in new ways. Watch every latent animosity in race relations come to the surface. British captains beat Indian pilots every time a boat runs aground; engineers beat the lascars feeding logs into the furnaces if the steam pressure falls; and soldiers beat the cooks if they make a mess of the grub. Passengers straight from England are often shocked.

Remember, in an alien and often threatening environment, it’s worth paying a premium for the reassurance of a European-style cocoon: a steam-hotel, albeit a poor one, gliding along the river while the guests sit on the decks.

Headline image credit: Indus Sunset by Ahmed Sajjad Zaidi. CC BY-SA 2.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

The post What to expect on your 19th century Indus river steamer journey appeared first on OUPblog.

Blog: An Awfully Big Blog Adventure (Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags: writing, sleep, modern design, bronte, 19th century, Joan Lennon, Add a tag

I've just finished reading a wonderful blog by Penny Dolan over on The History Girls, about a series of connections that lead her from a randomly-chosen book from her shelves, right through a whole string of 19th century names, fictional characters and relationships, all linked by a wooden-legged chap called W.E. Henley. Which made me think of Charlotte Bronte. Recently, she's been my W.E. Henley.

It started with a Facebook post - which sent me to the Harvard Library online site where they have been working on restoring the tiny books Charlotte and Branwell Bronte made when they were children - which led to my own History Girl post Tiny Bronte Books. (Please, if you go to have a look, scroll down to the bottom and watch the Brontesaurus video - you won't regret it.)

I'm in the midst of editing an anthology of East Perthshire writers called Place Settings and was delighted to read in one of the entries the author's interest in the Brontes, and how "... every night, the sisters paraded round the table reading aloud from their day's writings."

Then I got involved in a project run by 26, the writers' collective, in which writers were paired with design studios taking part in this year's London Design Show, and asked to write a response to one of their objects. I was given Dare Studio who were putting forward, among other lovely things, a new design - the Bronte Alcove.

The alcove is meant to be a private space within public places, blocking out the surrounding bustle and noise. Which made me think of bonnets. Which led me back to the internet, which led me, by way of images of hats, to the passage below, written by Elizabeth Gaskell on her visit to Charlotte at the parsonage:

I asked her whether she had ever taken opium, as the description given of its effects in Villette was so exactly like what I had experienced, - vivid and exaggerated presence of objects, of which the outlines were indistinct, or lost in golden mist, etc. She replied, that she had never, to her knowledge, taken a grain of it in any shape, but that she had followed the process she always adopted when she had to describe anything which had not fallen within her own experience; she had thought intently on it for many and many a night before falling to sleep, - wondering what it was like, or how it would be, - till at length, sometimes after the progress of her story had been arrested at this one point for weeks, she wakened up in the morning with all clear before her, as if she had in reality gone through the experience, and then could describe it, word for word, as it had happened. I cannot account for this psychologically; I only am sure that it was so, because she said it.

Which led me to wonder ... my own practice has always been to try not to think about work when I'm courting sleep. And I have rarely, if ever walked round my table of an evening, reading aloud from my day's work. But have I been losing out here? Do you do as Charlotte did? I would be most interested to know.

Meantime, I wait for the next popping up of my very own W.E. Henley.

Blog: The Fourth Musketeer (Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags: immigrants, 19th century, Add a tag

Recommended for ages 8-12

In this mash-up of fairy tale and historical fiction set in mid-19th century Norway, 14-year old Astri is sold by her aunt to a horrible (and lecherous) goat-herder to serve as his servant and more. Astri manages to not only escape but also rescue her younger sister, so that they can try to get to America, where her father has emigrated. With the goatman in pursuit, they must travel west of the moon, and east of the sun in this masterful story in which a 19th century immigrant's story is seamlessly mixed with Norwegian folklore and mythology. The novel features a terrific feisty, no-nonsense heroine very loosely based on the author's own ancestors.

Blog: The Fourth Musketeer (Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags: adventure, 19th century, women's history, picture-book, Add a tag

Recommended for ages 7-12.

In this picture book for older readers. Tracey Fern tells the little-known story of Eleanor Prentiss, an extraordinary woman who not only navigated a clipper ship but also set a record for the fastest time from New York to San Francisco, navigating around Cape Horn in a record-breaking 89 days, 21 hours.

If you're an avid movie-goer like I am, you may have seen the two major films this year set at sea, Captain Phillips and All is Lost. Such movies always make me think about the "olden days," when sailors navigated by the stars and a sextant. Doesn't it seem incredible? Even more incredible (but true) is the life of Eleanor Prentiss, born the daughter of a sea captain in 1814 and taught everything about ships, including navigation, by her father, perhaps because he had no sons. Certainly this education was highly unusual for a 19th century girl. The sea was in Ellen's blood, and, not surprisingly, she married a sea captain, who took her along on his merchant ships as her navigator.

When Ellen's husband was given command of a new, super-fast clipper ship, Ellen seized the opportunity to get as quickly as possible from New York to the tip of South America to San Francisco and the Gold Rush. Speed was of the essence for those looking for riches in the gold fields of California. The book portrays the considerable dangers of the voyage, including a period when the ship was becalmed (no wind, no movement!) and also the perilous stormy waters of the Cape. Fern does a terrific job of capturing the excitement of the journey, and Ellen's triumph when she sets a world record for the fastest time for this 15,000 mile voyage. The book is greatly enhanced by the beautiful water-color paintings of Caldecott-winning artist Emily Arnold McCully. The seascapes, and particularly the scenes of storms, are particularly effective. Back matter includes an author's note with further historical information, and suggestions for further reading, both books and websites, a glossary, and end pages which show a map of the Flying Cloud's 1851 Voyage.

Highly recommended for Women's History Month and for those looking for stories of strong, heroic women and girls!

Blog: OUPblog (Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags: earning, clarendon, incomes, *Featured, payments, Simon Eliot, author earnings, author payment, Clarendon Press Series, History of Oxford University Press, John Feather, nonfiction authors, Selborne Commission, W. Aldis Wright, aldis, ‘clarendon, liddell, Books, History, Media, Oxford University Press, wright, British, 19th century, Add a tag

By Simon Eliot and John Feather

In the 1860s, the introduction of its first named series of education books, the ‘Clarendon Press Series’ (CPS), encouraged Oxford University Press to standardize its payments to authors. Most of them were offered a very generous deal: 50 or 60% of net profits. These payments were made annually and were recorded in the minutes of the Press’ newly-established Finance Committee. The list of payments lengthened every year, as new titles were published and very few were ever allowed to go out of print. Some authors did very well from their association with the Press, but most earned very modest sums. Many of the books in the Clarendon Press Series yielded almost nothing to publisher or author; once we exclude the handful of exceptional cases, typical payments were in the range of £5 to £15 a year.

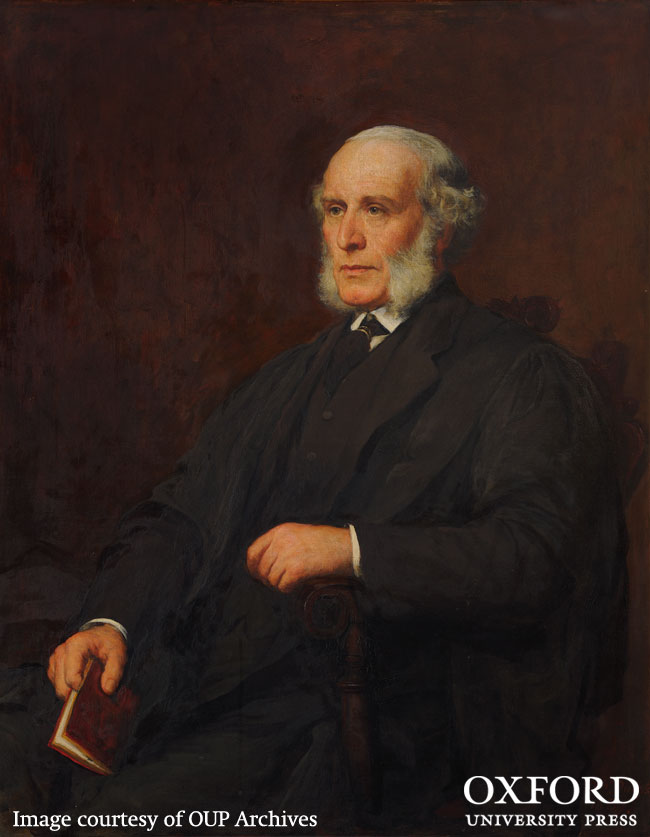

W. Aldis Wright.

The outstanding financial successes of the Clarendon Press Series were the editions of separate plays of Shakespeare intended for school pupils and (increasingly) university students. The first to be published was Macbeth in 1869, but it was the next to appear – Hamlet in 1873 – which became something like a bestseller. In its first year, Hamlet sold 3,380 copies; 20 years and five editions later, 73,140 copies had been accounted for to the editor, W. Aldis Wright (a fellow of Trinity College, Cambridge), who received over the years some £1,400 for this play alone. The whole CPS Shakespeare venture brought Wright an income of about £1,000 a year throughout much of the 1880s. To put this in context, the total of all royalties paid to authors in the late 1880s and early 1890s was about £5000 a year; in some years Wright was taking about 20% of that for his editions of Shakespeare alone.

A broader view of the Press’s payments to its authors on the Learned side can be gained by looking at three sample years: 1875, 1885, and 1895. In November 1875, the Finance Committee minutes listed 99 titles for which authors were being paid annual incomes, the total sum being paid out was £2,216. In November 1885, near the peak of publishing activity in the Clarendon Press Series, the Finance Committee minutes listed 238 titles generating revenue for their authors; they earned £4,740 between them. In November 1895, there were 240 titles leading to payments of £5,076. For most authors, their individual incomes were modest; in 1875, the median income was £7 16s, in 1885 it was £7 18s. However, in 1875 four authors and editors earned more than £100: Liddell and Scott received £372 each (for their Greek Lexicon), Aldis Wright received £220 (for various editions of Shakespeare’s plays), and Bishop Charles Wordsworth £152 (for his Greek Grammar). In 1885, eleven were earning more than £100, including Aldis Wright earning £934, Liddell and Scott each earning £350, Skeat earning £270 (for philological works), and Benjamin Jowett earning £261 (for editions of Plato’s works). In 1895, there were ten, including Aldis Wright with £578, J. B. Allen with £542 (for works on Latin grammar), and Liddell and Scott with £389 each.

These authorial incomes should be set against average academic incomes in Oxford. In the later nineteenth century, although there was much variation, the average annual income for a college fellow would be in the order of £600, usually made up of the fellowship dividend plus the tutorial stipend. In the wake of the Selborne Commission, in the early 1880s a reader would be paid £500, a sum might well be augmented by a fellowship dividend; professorships attracted £900 per annum. It is clear that, although most authors’ incomes were extremely small, the most successful authors, both inside and outside the Clarendon Press Series, were at their height earning a significant addition to their salaries through payments from the Press.

The incomes of the most successful were far in excess of what they would have earned had they sold their copyrights outright. On the other hand, those around the median probably earned less than a lump sum payment would have brought in or, at least, they had to wait longer for it. As a minor compensation to those who were paid small annual sums during this period – though it is unlikely that they would have known it – the purchasing power of the pound was rising between the mid-1860s and the mid-1890s, so their later small payments would have bought them more than their earlier small payments. The pound in a person’s pocket was actually worth more at the end of the nineteenth century than it had been at the beginning.

Simon Eliot is Professor of the History of the Book in the Institute of English Studies, School of Advanced Study, University of London. He is general editor of The History of Oxford University Press, and editor of its Volume II 1780-1896. John Feather, a former President of the Oxford Bibliographical Society, is a Professor at Loughborough University and the author of A History of British Publishing and many other works on the history of books and the book trade. He has contributed to both volumes I and II of The History of Oxford University Press.

With access to extensive archives, The History of Oxford University Press is the first complete scholarly history of the Press, detailing its organization, publications, trade, and international development. Read previous blog posts about the history of Oxford University Press.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only British history articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Image credit: William Aldis Wright (1831-1914), editor, Shakespeare Plays, the Clarendon Press Series (Walter William Ouless, 1887). (The Master and Fellows of Trinity College Cambridge) OUP Archives. Do not reproduce without permission.

The post How much could 19th century nonfiction authors earn? appeared first on OUPblog.

Blog: The Fourth Musketeer (Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags: biography, 19th century, women's history, Add a tag

Blog: The Fourth Musketeer (Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags: young adult, England, 19th century, women's history, Add a tag

Release date: January 1, 2013

Recommended for ages 10 and up.

Carolyn Meyer's series The Young Royals has examined the youth of many of history's most prominent royal female figures, including Queen Elizabeth I, Marie Antoinette, and Cleopatra. It's perhaps inevitable that she would turn her attention to the most important female queen of the 19th century, a figure so prominent she gave her name to an entire historical period, Queen Victoria. The book spans from 1827, when Victoria was eight years old, to 1843, by which time Victoria was a young queen with three children.

Meyer tells her story through diary entries based on Victoria's own diaries, which she began keeping at the age of thirteen. (Note: in 2012, the entire contents of these diaries were made available online). T As Meyer explains in an afterword, these diary entries were written in the knowledge that they would be read, at first by her mother and governess, and later by historians. Meyer uses her imagination (and research of course) to describe what Victoria is really feeling, but incorporates many of Victoria's stylistic quirks, such as an affection for writing in all capitals or underlining dramatically, to give the feel of her actual diaries.

I really enjoyed this novel, and felt it did a terrific job of capturing Victoria's strong personality and opinions, both as a young girl and as an adult. We learn many details of Victoria's daily life, from her strained relationship with her mother and her advisor, Sir John, to her attachment to Dash, her mother's King Charles Spaniel. Even when you're a privileged princess, you don't necessarily get your way, and Victoria's wishes are often thwarted by her mother or court intrigue. Even when she becomes queen, her struggles with her mother are not over, although Victoria takes control of many aspects of her court, including her personal household. In addition to dealing with all the intrigues of court life, Meyer also takes us into Victoria's confidence as she is wooed by and eventually weds her cousin Albert, the love of her life. Even with Albert, however, there were inevitable conflicts, as the young couple tried to adjust to their different roles--queen, sovereign, wife, and mother, and prince consort, husband, and father.

An afterword provides additional information on the rest of Victoria's life and other historical notes, as well as a bibliography and a list of related websites to visit.

Those who read this novel should certainly get a copy of the DVD of The Young Victoria, the beautifully realized 2009 film starring an elegant Emily Blunt as the young monarch. Another appealing novel for young readers with the young Victoria as a prominent character is Prisoners in the Palace by Michaela Maccoll (Chronicle, 2010).

Disclosure: advance copy provided by publisher.

Blog: The Fourth Musketeer (Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags: immigrants, middle grades, 19th century, 1900-1940, Add a tag

Recommended for ages 9 and up.

Author Gwenyth Swain brings stories of Ellis Island vividly to life through text and photographs in the beautifully rendered Hope and Tears: Ellis Island Voices. She uses poetry, monologues, and dialogues combined with a selection of archival photographs to help us imagine Ellis Island at various stages of its existence, beginning in the late 1500's with a poem by a native Lenni Lenape boy.

Prose introductions provide background on each period of Ellis Island's history, from the processing of its first immigrant in 1892 to its busiest period in the early 20th century and beyond. In moving free verse, Swain chronicles all aspects of Ellis Island's life, from the arrivals, complete with their hopes and dreams, to the dreaded inspections, in which families could be separated and detained in hospital's on the island or even sent back if they were deemed "likely to become public charges." She doesn't forget the various workers on the island, from the nurses and aid workers to the clerks, cooks, and Salvation Army volunteers, who are pictured handing out doughnuts to hungry immigrants.

In the 1920's, when Congress put limits on immigration, Ellis Island became a place mostly used for deportation rather than immigration, and eventually was abandoned after 1954. But in the preparation for the nation's bicentennial, interest in Ellis Island as an important historical landmark surged, and in 1990, after many years of renovation and fundraising, the island reopened as an immigration museum. Additional poems mark this more recent period of Ellis Island's history as well, ending with a poem from a National Park Service employee, who remarks about the many visitors:

...maybe they feel what I feel./The sense that,/after all these years,/spirits live here,/along with all their hopes and tears.This book would be perfect for a class performance as part of a unit on family history and immigration. There are many parts for boys and girls and only simple costumes--or no costumes at all--would be required.

Back matter includes source notes, a bibliography which includes websites, films, books, articles, and interviews, an index, and suggestions for going further in exploring the themes of this book. Swain's website will also offer an extensive teacher's guide (available soon).

Blog: The Fourth Musketeer (Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags: 19th century, Jewish history, France, time travel, Add a tag

Recommended for ages 9-14.

Author-illustrator Marissa Moss has two excellent new historical fiction novels for young people out this fall: Mira's Diary: Lost in Paris and A Soldier's Secret. Today I will be reviewing the first of these, and a review of the Civil War historical thriller A Soldier's Secret will be coming next week in my blog.

In Mira's Diary, Moss creates a time travel story melding the exciting artistic world of 19th century Paris with the shocking political intrigue and anti-Semitism of the infamous Dreyfus affair. Although the Dreyfus affair is well known to those interested in French history, it's certainly not a topic most young people in the U.S. will be at all familiar with, and I applaud Moss for choosing to set her story around this important tale of corruption and scapegoats.

Our story begins when young Mira receives a strange postcard of a gargoyle from Notre Dame in Paris from her mother, who has been missing without any explanation for many months. Not only is the black and white postcard very old-fashioned looking, so is the faded French stamp. And "who sends postcards anymore?," wonders Mira.

With the postcard their only clue, Mira, her father, and her 16-year old brother take off to Paris, hoping to find her mother. They check into a quaint hotel in the Marais, Paris' historic Jewish quarter, before going off to explore the famous cathedral. Mira can't help looking everywhere for her mother, but it's not until she touches a gargoyle on the top gallery of the cathedral that she realizes she's been looking in the wrong century! Magically transported to April, 1881, Mira not only befriends a good-looking young man who turns out to be an assistant to the famous French artist Degas, she also finds herself embroiled in the Dreyfus affair, a political scandal that involved the French army and virulent anti-Semitism in the French military and society at large. Mira spots her mother several times, and receives several mysterious and secret notes from her. It's clear that her mother is in danger, and Mira must step up to try to keep Dreyfus, a Jewish army officer, from being unjustly punished as a traitor.

This novel manages to mix very serious topics such as prejudice and anti-Semitism with an up-close look at late 19th century Parisian artistic life, letting us visit Giverny, Montmartre, the Impressionists Exhibition, and Parisian salons populated by famous artists such as Degas, Monet, Seurat, and Mary Cassatt. Moss even throws in a hint of romance between Mira and Degas' handsome young assistant Claude. Although readers will learn a lot about history and art through this book, they will also be entertained by the suspenseful story featuring a likable heroine who finds herself in a difficult--and certainly unusual--situation.

In the manner of her Amelia's Notebook series and her historical journals, Moss gives this new book the feel of a real journal or diary, from the cover with its mock journal binding to the charming small pencil sketches distributed liberally throughout the novel and the endpapers decorated with Mira's notes to herself, a map of France, and French vocabulary.

An extensive author's note provides a detailed explanation of the complexities of the Dreyfus affair (geared for tween readers) and the military corruption and anti-Semitism it exposed in 19th century Paris. Moss also provides brief notes on Paris in the late 19th century, the impressionist art movement, and author Emile Zola, who wrote the famous "J'accuse" newspaper article in favor of Dreyfus. A bibliography lists other resources and books consulted by the author.

Blog: The Fourth Musketeer (Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags: young adult, France, 19th century, Add a tag

Recommended for ages 12 and up.

Susanne Dunlap is a favorite author of mine for YA historical fiction with a romantic flair, books that will realistically appeal much more to girls than to boys. This is her fourth YA title (she has also written historical fiction aimed more at adults) and the first set in France.

In this new novel, Eliza, the young daughter of future U.S. President James Monroe, is in France with her mother, where she is left behind in a chic boarding school just outside the city that's run by a former courtier to Marie Antoinette, Madame Campan. The school is attended by France's finest young ladies, including Caroline Bonaparte, the youngest sister of the up-and-coming French general, as well as Hortense Beauharnais, the daughter of Napoleon's wife, Josephine. The book is set in the turbulent year 1799, the year in which Napoleon overthrew the French Directory and took power for himself as First Counsel, leading of course to his eventually crowning himself Emperor (although not in the course of this novel).

The book alternates between four different narrators: Eliza, Hortense, Caroline, and Madeleine, the mixed-race--and of course entirely unsuitable--daughter of a cruel, drug-addicted Paris actress. Eliza quickly picks up on the bad blood between Hortense and Caroline at school, wondering what role she will play in the school's hierarchy of students. All the girls seem much more concerned with their love lives than any studying, not too surprising since their primary curriculum seems to be learning how to talk prettily to young gentlemen, including the lads from the nearby boys' school who sometimes visit for training exercises. But the school's far from boring. There seems to be plenty of intrigue, with Caroline whisking innocent young Eliza off to a clandestine party in Paris when they're supposed to be asleep in bed. All the girls develop crushes on the wrong sort of man--Hortense on a music teacher, Caroline on a general that her brother doesn't want her involved with, and both Eliza and Madeleine, the actress' daughter, on Hortense's handsome brother, Eugene. Will anyone wind up with the man of their dreams? You'll have to read on to the shocking ending to find out.

And in the middle of all of this romantic drama, there's a political drama behind the scenes, a possible coup, one that the girls are determined to witness, even dressing up as soldiers to sneak off and see what's going on. Not to mention Eliza's trying to come to terms with her racial attitudes from growing up with slaves on a Southern plantation.

Although I greatly enjoyed The Academie, I can't say it's my favorite of Dunlap's novels. I found it occasionally confusing switching back and forth between the different narratives, and I found it hard to suspend my disbelief at some of the girls' dangerous antics, which seemed a bit far fetched for young girls in this setting.

An author's note explains that while all three of her main characters (Eliza, Hortense, and Caroline) indeed attended the same boarding school, they were probably not all three there at the same time and the author admits to taking some liberties with the actual timeline in structuring her story. Nonetheless, the real Eliza and Hortense remained friends and Eliza even intended Napoleon's coronation as emperor in 1804. And the rivalry between Napoleon's family and Josephine and her children is a well-established historical fact.

This novel

Blog: The Fourth Musketeer (Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags: 19th century, African-American history, Add a tag

Recommended for ages 8-12.

Another excellent choice for Black History Month, this historical fiction novel for middle-grade readers, takes a little known race riot and coup d'etat that occurred in Wilmington, North Carolina, in 1898 as the inspiration for creating a compelling story of eleven-year old Moses and the destruction of the middle-class African-American community in which he lived.

It's just one generation after the end of slavery--Moses' own grandmother, Boo Nanny, was born a slave, but in the years since Emancipation, Moses' family has risen into the middle class. His father is college-educated, works for the local black newspaper, and is also a town alderman. When the editor of the black newspaper writes an editorial in which he suggests that it's no worse for a black man to be intimate with a white woman than for a white man to be intimate with a black woman, "big trouble's a-brewing" in Wilmington. Will Moses and his family escape the ensuing violence that erupts?

Creating a compelling voice for young Moses, author Barbara Wright has created a moving and shocking story about the Jim Crow South that received well deserved star reviews from Kirkus, Publisher's Weekly, School Library Journal, and Horn Book. You can read an excerpt at her website. Her website also offers resources for teachers, including a teacher's guide from Random House. This book is a must-have for school and pubic libraries!

Blog: The Fourth Musketeer (Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags: young adult, 19th century, Add a tag

Recommended for ages 10 and up.

Unfortunately I've never read Dee Brown's iconic Bury My Heart at Wounded Knee, the best-selling history of the American West from the point of view of the Native Americans that was first published in 1971. In this new book written for younger readers, Dwight Jon Zimmerman has adapted Brown's 500+ page book for a younger audience, adroitly simplifying but not "dumbing down" the complex and interwoven stories of the different Indian tribes in the original by concentrating on the Great Sioux Nation. As Zimmerman explains in his preface, the Sioux's epic fight against the white man represents the struggle of all the Indian nations in many ways, and includes the stories of some of the most famous warrior chiefs in Indian history, among them Sitting Bull and Crazy Horse, as well as some of the most famous battles and events.

Zimmerman condenses and abridges Brown's work to concentrate on the Sioux' story, but also adds a first chapter providing background on the Sioux people as well as an epilogue discussing what has happened to the Sioux since the infamous massacre at Wounded Knee in 1890, and their attempts through the U.S. courts in modern times to get their sacred lands, the Black Hills, returned to them.

I must comment that I found this an incredibly difficult book to read; not because of complicated vocabulary or poorly written narrative, but because of the tragic nature of the material. In fact, the book made me think about how many narratives of the Holocaust I have read, and yet how this tale of the white man's betrayal again and again of the Native Americans was so hard for me to digest. That's perhaps a topic for another blog post, but even in stories (whether fiction or non-fiction) of the Holocaust there's a few good people who tried to rescue Jews or otherwise help them, whereas it doesn't seem like any of the white people appreciated the Indians' culture and lifestyle at the end of the 19th century. Undoubtedly there must have been some more forward looking whites, but where were they? Putting the Indian children into boarding schools to train them to be "white", it seems.

This narrative starts in the years leading up to the Civil War, in which the Sioux of Minnesota agreed in treaties to surrender nearly all their land, thus having to learn to farm like white men and depending on annuities from the government, and covers the story of the Indian Wars that ensued over the next thirty years. Over and over again the Sioux were betrayed by the U.S. government, who would appear to negotiate treaties in good faith that they seemed to have no intention of keeping. The narrative is magnificently illustrated with many full page photographs of various Sioux chiefs as well as American leaders, maps, as well as historic paintings and lithographs. Zimmerman allows the Sioux leaders to tell their own stories, continuing Dee Brown's practice of including ample primary source materials (primarily oral histories).

Zimmerman concludes his narrative with the incredibly powerful quote that seems to sum up everything that happened to the Native population of this country from the time the white man first landed:

"They made us many promises, more than I can remember, but they never kept but one; they promised to take our land, and they took it." --Red Cloud

This book includes abundant backmatter, including a timeline of Sioux history from 1851 to 1909, a glossary, information on the Sioux calendar, recommended reading, suggested websites, and an

Blog: The Fourth Musketeer (Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags: mystery, immigrants, 19th century, Add a tag

Recommended for ages 10-14.

Avi, Newbery award-winning author of more than 60 novels for children and teens, turns once again to historical fiction in his newest novel, set in 1893 New York City. His hero, thirteen-year old Maks, makes a bit of money as a newsboy to help his impoverished immigrant family on the lower East Side. When his older sister, Emma, who works as a maid at the swank Waldorf-Astoria hotel, is falsely accused of theft and imprisoned in the city prison ominously called the Tombs, Maks teams up with a homeless girl, Willa, to try to clear his sister's name and free her from jail. At the same time, he has to avoid landing in the clutches of the Plug Ugly gang, whose boss is trying to take control of all the newsies. Confronted with a mystery whodunit, Maks enlists the help of a dying lawyer to find the true culprit of the theft at the hotel.

Avi knows how to spin a convincing tale, and this book is no exception. In his afterword, he notes that the book is his attempt to "catch a small bit of how New York City kids lived at the end of the nineteenth century." He's particularly adept at evoking the sounds, smells, and look of tenement life in New York, with its mix of poor immigrants from many nations. This poverty contrasts with the swank brand-new Waldorf Astoria, where Maks winds up working under cover to try to clear his sister's name. Avi uses a very colloquial voice to tell the story, with the narrator speaking directly to the reader. While I understand the use of a strong point of view, I was irritated by the way he tries to evoke the dialect of the time, with plenty of dropped letters, i.e. "'cause' instead of "because", 'bout' instead of "about," 'em' instead of "them," etc.

Avi includes an Author's Note with historical details about the period, as well as suggestions for further reading and viewing.

City of Orphans is definitely worth reading, and will be enjoyed by young people who like a historical mystery, but it would not be one of my favorites among Avi's works.

Blog: The Fourth Musketeer (Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags: adventure, frontier, 19th century, picture-book, Add a tag

Recommended for ages 5-10.

This stunning new picture book, written by Donna Jo Napoli and majestically illustrated by Jim Madsen, tells the story of the Lewis and Clark expedition from the point of view of its youngest participant, baby Jean Baptiste, son of Sacagawea. Strapped onto his mother's back in a cradle board, the baby comments on the various sights and sounds of the expedition. The narrative is written in free verse. Here is an example from the book's opening:

"Rolled in rabbit hide/I am tucked snug/in a cradle pack/in the whipping cold/of new spring./Roar, roar! Grizzlies stand tall in my dreams."

The vibrantly colored two page illustrations effectively capture the grandeur of the American wilderness that is all around the expedition's participants. Jean Baptiste observes eagles, cougars, grizzlies, salmon, elk, birds, and other wildlife that were abundant at the time, as the group makes its way to the Pacific and then back to their home.

An author's note provides some historical context on the journey tiny Jean Baptiste and Sacagawea embarked upon from Fort Mandan, North Dakota to the Pacific and back again. While this book does not give young readers a complete picture of the Lewis and Clark expedition, it would make an excellent class read-aloud or supplement for home schoolers studying Lewis and Clark, allowing students to imagine the journey from an unusual point of view. The illustrations are also wonderfully evocative of another time and place in American history, a time when the frontier was vast and the country ripe for exploration.

For another point of view on the Lewis and Clark Expedition, elementary students might try my favorite book about the expedition, New Found Land by Allan Wolf (Candlewick, 2004), which tells then story from the point of view of 13 different participants, including Lewis' dog, Seaman. Other historical novels worth consideration are The Captain's Dog: My Journey with the Lewis & Clark Tribe, by Roland Smith (Sandpiper, 2008); Kathryn Lasky's The Journal of Augustus Pelletier: The Lewis and Clark Expedition, 1804 (My Name is America) (Scholastic, 2000),

Blog: The Fourth Musketeer (Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags: young adult, paranormal, England, 19th century, Add a tag

Recommended for ages 12 and up.

Violet doesn’t believe in ghosts--how could she after her exposure to all the tricks of her mother’s medium trade? So no one is more astonished than Violet when, at the first of her mother’s seances at Lord Jasper’s estate, she sees a girl in the shadows, dripping water. Here’s Harvey’s creepy description of Violet’s first ghost sighting:

Blog: The Fourth Musketeer (Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags: young adult, paranormal, debut author, frontier, 19th century, Add a tag

With The Revenant, which hits bookstores today, debut author Sonia Gensler has crafted a historical fiction/paranormal romance page turner perfect for teen summer reading. Our heroine is seventeen year old Willie--a self-described liar and a cheat. Desperate to avoid having to return home to help her mother take care of her young half-brothers, she fakes educational credentials to get hired as an English teacher at the Cherokee Female Seminary in Indian Territory.

0 Comments on Book Review: The Revenant, by Sonia Gensler (Alfred A. Knopf Books, 2011) as of 1/1/1900

Blog: The Fourth Musketeer (Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags: middle grades, frontier, 19th century, Add a tag

Recommended for ages 8-12.

Jennifer Holm's 1999 novel Our Only May Amelia (which received a Newbery Honor in 2000) is one of my all-time favorite historical novels for kids, and I was eager to read the sequel which has just been released this spring. If you haven't read the first book, May Amelia is the only girl in a large family of Finn immigrants living in a remote area of Washington State around 1900. Amelia fits into the tradition of feisty tomboy frontier girls like Laura Ingalls, and her first story both made me laugh and made me sob (no spoilers, for those who haven't read it).

While the sequel doesn't quite pack the emotional wallop of the first book, I greatly enjoyed this book as well. In fact, I felt like I was visiting an old friend whom I hadn't seen in quite some time, one I was glad to catch up with. How to describe 12-year old May Amelia? Holm opens the book with the following description: "My brother Wilbert tells me I'm like the grain of sand in an oyster. Someday I will be a Pearl, but I will nag and irritate the poor oyster and everyone else until then." Her Pappa tells her "he would rather have one boy than a dozen May Amelias because Girls Are Useless." She lives in the middle of nowhere with no girls to keep her company, and she's always being teased by her seven older brothers. Her father not only runs the family farm but also works at a nearby logging camp for extra cash.

When a quick-talking stranger comes to town, May Amelia finally proves useful to interpret for her father from English to Finnish. The stranger's looking for investors to develop the land around the Nasel river, and assures Pappa he has powerful supporters. Pappa would have to mortgage the farm, but is this a once in a lifetime opportunity to bring the family out of poverty and into prosperity? And will May Amelia finally demonstrate to her father that she has "sisu", or guts?

This story is based on the author's own family history, in particular that of her great-grandfather, who settled on the Nasel River in 1871. But it is young May Amelia who's the star of this funny but also moving tale of the Western frontier. She's one of those characters who stays with you long after you've finished her story. I'd love to see Jennifer Holm continue with more stories about May Amelia as she grows up. But I hope we won't have to wait twelve years for the next installment!

For more great books for tweens, check out Green Bean Teen Queen's weekly meme, Tween Tuesday.

Blog: The Fourth Musketeer (Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags: young adult, Africa, 19th century, Add a tag

I am delighted to participate in Tundra Books' blog tour for a moving new novel for young people set during South Africa's Boer War, Stones for My Father. Written by novelist Trilby Kent, who was born in Canada but currently lives in London, this book is her second published novel for young people.

One of the reasons I enjoy historical fiction so much is that it can take you to a place and time you've never experienced. In this case the backdrop for the story is the Boer War, which was disastrous for the British, who are driving the Boers from their farms. We experience this chaotic time through the eyes of Corlie Roux, a skinny young girl living with her stern mother and younger siblings in the Transvaal. Most of the Afrikaner men and young boys are off fighting the British, but Corlie's father is already in the graveyard, having died of consumption. Corlie's only friend seems to be Sipho, an African boy who is her matie, or playmate, and who teaches her the ways of the bush, telling stories together and fishing and tracking animals with her.

But when she and Sipho see the English "khakis" nearby, Corlie and her family flee to the laager, groups of Boers hiding out in the bush. On their journey, Corlie watches helplessly by as she sees their family farm burned by the British. While foraging for food, Corlie and her brother meet a kind Canadian soldier--a Khaki, but one who provides them with some precious meat. They finally meet up with the laager after a trek of many days across the veld, but their safe haven is short lived. Soon discovered by British soldiers, Corlie and all the others are forced to surrender, then sent to a "voluntary refugee camp," which more resembles an internment camp, where the conditions are harsh indeed, with scarce food, water, or other resources for the thousands of women and children imprisoned there. Corlie and her family are "undesirables"--those whose menfolk were still fighting the British, and were given the lowest rations. Soon the children are "numb with boredom," and worse yet, are falling ill to typhoid and other diseases brought on by malnutrition and unsanitary conditions at the camp. Corlie's soon fighting for her life, and her self-worth, discovering a secret about her father that we could only guess at as we read her story, and a secret that reunites her with the kind Canadian whose destiny becomes intertwined with Corlie's.

Kent does a wonderful job evoking the African bush, with "days...so hot that even raindrops would sizzle as they hit the dry earth." She also captures very effectively the inhumanity of war, with the hardships it creates on ordinary civilians, particularly innocent women and children, in her depiction of the "refugee camp." The book includes a very brief epilogue with some historical information; for U.S. readers, most of whom have no familiarity with this period in history, some additional background might have been helpful. I would have enjoyed seeing something more detailed to set this story in better historical context.

Blog: The Fourth Musketeer (Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags: young adult, frontier, 19th century, women's history, Add a tag

Release date: April 4, 2011

Recommended for ages 12 and up.

Debut novelist Carole Estby Dagg was inspired by her own family history to write the delightful new young adult historical novel, The Year We Were Famous. Based on the true story of the author's great-aunt and great-grandmother, this adventure-filled novel set at the time of the suffragist movement tells the tale of 17-year old Clara Estby and her mother, Helga, who decide to walk clear across the United States from the small Norwegian-American farming community of Mica Creek, Washington to New York City--some 4,000 miles--to save their family farm from foreclosure. Helga, a dedicated suffragist, also wanted to prove that women deserved the vote, because a woman was resourceful enough to make it across the country on her own, without a man's help. All this, in an era when most women never went more than a few miles from their home.

The story, told in the first person by Clara, opens with Clara, the eldest of eight children, having returned from high school in Spokane to her family's farm in Mica Creek. While brainstorming about ways to raise money to save their farm, her mother comes up with her idea of walking across the country, and begins seeking sponsors. At her pa's suggestion, Clara agrees to go along on an adventure that she can't begin to imagine: "This would be my year abroad, my year to turn the old Clara into someone bold, someone with newfound talents, strengths, and purpose in life." And when a New York publisher offers them $10,000 if they complete the trip by November 30, 1896, they are on their way, equipped with calling cards, a letter from the mayor of Spokane attesting to their moral character, work boots, canteens, oil-skin ponchos, tooth powder and toothbrushes, two journals and six pencils, a second-hand satchel, and a compass given to Clara by Erick, the boy who's sweet on her--but no change of clothes!

Needless to say, Clara and her mother have no shortage of adventures on the way, as they follow the train tracks East, including encounters with Native Americans, outlaws, handsome journalists, and even the President-Elect and First Lady of the United States, not to mention blizzards, flash flood, lava fields, heat, thirst, and a sprained ankle. Will they make it to New York on time to collect their prize and save the farm? You'll have to read this to find out. I, for one, had a hard time putting this book down.

Author Dagg does an outstanding job bringing the voices of her intrepid ancestors to life; she extensively researched the lives of Victorian women in order to "get inside Great-Aunt Clara's head." Teens are likely to identify with Clara's personality clashes with her mother, as well as her dreams of a life more exciting than being a farmer's wife in rural Mica Creek and her struggle between family obligations and becoming independent.

An excellent website for the book offers more information on historical context and discussion themes; this would be a particularly appropriate title for a mother-daughter book club, and although the protagonist is seventeen, the book would be perfectly appropriate for readers as young as ten.

Blog: The Fourth Musketeer (Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags: young adult, mystery, England, 19th century, Add a tag

Recommended for 10 and up.

Sherlock Holmes is one of the most beloved fictional characters ever created, and the original Arthur Conan Doyle stories remain popular, as do many spin-offs in both books and film for adults and young people. A new series by British writer Andrew Lane imagines Sherlock as a fourteen-year old boy solving his first murder mysteries. The first volume in this series, Death Cloud, starts off a bit slowly but soon turns into an intriguing murder mystery.

Andrew Lane writes that his intention with this series is "to find out what Sherlock was like before Arthur Conan Doyle first introduced him to the world. What sort of teenager was he? Where did he go to school, and who were his friends? Where and when did he learn the skills that he displayed later in life – the logical mind, the boxing and sword-fighting, the love of music and of playing the violin? What did he study at university? When (if ever) did he travel abroad? What scared him and who, if anyone, did he love?" Arthur Conan Doyle, notes Lane, gave away little about Sherlock's youth in his published short stories and novels, except a few hints here and there, therefore giving Lane considerable creative license to create the early years for this beloved character.

Set in 1868, when our hero is fourteen, our novel opens with Sherlock at boarding school. But instead of going home for his summer vacation, he finds out from his brother Mycroft that their father has been posted to India, their mother is "unwell," and Sherlock will have to spend the summer with his peculiar aunt and uncle--who he's never even met--in Hampshire. The only bright note seems to be that the food is better than at school.

But things won't be boring for long, as Sherlock makes friends with a local boy, Matty, who's been witness to a strange mysterious smoke and a dead body covered in boils. Has the plague come back? Matty serves as a younger version of Watson in this story, assisting Sherlock with his investigations. Sherlock is also helped by his American tutor and his feisty and independent daughter Virginia, Sherlock is soon involved with fire, kidnapping, espionage, and murder. Will his powers of deduction help him solve his first murder, while uncovering an evil plot to bring down the British Empire? (this seems more James Bond to me than Sherlock Holmes, but perhaps that's just a contemporary perspective!)

I should disclose that I have not read any of the original Sherlock Holmes stories, but that may be the case as well with the intended audience for this series, teens and tweens. This new series is not the first about Holmes to be aimed at teen readers, but is the first such series endorsed by the Arthur Conan Doyle estate. (A different series for teens,the award-winning The Boy Sherlock Holmes, by Shane Peacock, was first published in 2007 by Canadian publisher Tundra Press and has four volumes to date. I have not read any of the titles in that series but it would be interesting to compare and contrast how both authors imagine Sherlock as a youth). And then of course we have the acclaimed Enola Holmes mystery series by Nancy Springer, concentrating on Sherlocks' much-younger sister, Enola, a talented detective in her own right.&n

Blog: The Fourth Musketeer (Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags: adventure, young adult, 19th century, women's history, Add a tag

Recommended for ages 12 and up.

Release date: April 12, 2011

Susanne Dunlap is fast becoming one of my favorite YA historical fiction authors; her third novel for teens, In the Shadow of the Lamp, follows the adventures of 16-year Molly Fraser, as she joins the nurses traveling with Florence Nightingale to the far-off Crimean war. As the novel opens, Molly loses her job as a chambermaid in one of London's aristocratic mansions when she is unjustly accused of stealing. With no letter of reference, there are few respectable options open to her for employment. Although she is too young and inexperienced to gain employment as one of Miss Nightingale's corps of nurses, by her wits she manages to sneak aboard their ship. When she is found out, the very imposing and strict Miss Nightingale is impressed by Molly's determination to redeem herself and decides to give her a chance to be trained on the job. She warns her that at the first sign of familiarity with any man, she'll be sent packing!

But somehow we know romance will be in Molly's future (this is a YA novel, after all). And not only one handsome young man is after her, but two: Will with the kind eyes, the valet who follows Molly by enlisting in the British army; and Dr. Maclean, a Scottish doctor at the hospital who Molly is intensely attracted to. And Molly finds friendship, too, with another young nurse, Emma. Molly begins to earn the respect of the other nurses when she helps take care of all the ones suffering from seasickness during the ocean voyage to Turkey. Soon they land, and she is amazed by the sights, sounds, and smells of Scutari, where they arrive shortly after the famous charge of the Light Brigade has produced hundreds of casualties, soon to arrive by ship. But when the nurses arrive at the hospital, it's Molly's cleaning and mending experience that comes in handy--the place is filthy, filled with giant rats and lice,with overflowing latrines and piles of mending and washing to be done.

Dunlap makes sure to share some of Nightingale's philosophy of nursing, which was not just to do with giving medicine and bandages. As strange as it seems to us now, her message was revolutionary at the time: provide the sick and wounded with fresh air, warmth, and food, so that their bodies would heal. She soon whips the hospital in Scutari into shape, securing supplies such as beds, fresh straw for mattresses, linens, even curtains to shield the patients from each other when the doctors were performing surgeries. We see her through Molly's eyes, visiting the wards at night with her famous lamp, making sure the men were safe.

Can Molly make something of herself as a nurse? Will she be able to handle the hard work, the horrible sights and smells of the hospital, and Miss Nightingale's strict rules of behavior?

Once again Susanne Dunlap has created an incredibly sympathetic character as her protagonist. Young Molly is far from perfect but is the type of young woman you'd want on your side in a difficult situation--like being at a battlefield hospital far from home. This book combines romance, adventure, and history with an appealing plot and characters with teen appeal. A great pick for public or school libraries!

Blog: The Fourth Musketeer (Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags: middle grades, 19th century, Add a tag

Recommended for ages 10 and up.

Release date: February 15, 2011

Author Anna Myers' newest historical novel for children is a dark tale indeed, opening with a creepy graveyard scene in which young Robby and his Da steal a corpse from a freshly made grave. The theft is described in great detail, as poor Robby has to get into the grave with the corpse in order to help his father remove the body. As long as they leave the clothes and any valuables, no crime was considered to have been committed. The body, that of a young girl, is then sold to the medical school, where Robby meets Dr. Bell, the head surgeon. Robby is disgusted by this work, but his father insists Robby help him, threatening otherwise to take Robby's mother along.

Robby's mother runs a boarding house in 19th century Philadelphia, with only one lodger, the kind but very elderly Miss Stone. But it appears their luck might be changing when an important-looking man, William Burke, shows up with his young daughter Martha to rent rooms. Robby's intuition tells him that something about Burke is sinister, and when he follows him to see what he's up to, he discovers Burke is a professional gambler. But there's more to Burke than gambling, and soon he gets Robby's Da involved in his schemes. Now Robby doesn't have to go robbing graves during the night anymore, and indeed he gets a small job working for Dr. Bell at the medical school. But there's a truly evil project going on right under Robby's nose: one that results in several murders carried out right in the boarding house! Can Robby expose Burke's evil-doing without leading his own father straight to the executioner?

An author's note explains how this book was partly inspired by the infamous case of Burke and Hare, who committed a series of gruesome murders in a Scotland boarding house in order to sell the bodies to medical schools. The publicity about this case led to a law passed in Great Britain making it a crime to take bodies and at the same time providing that unclaimed bodies be given for medical school use. Grave robbing was prevalent in the United States as well.

Although the publisher recommends this book for ages 8-12, I would suggest the book for middle schoolers (10-14) because of the very dark nature of the content. The story itself is well paced and exciting, and could be a good choice for reluctant readers looking for a historical title, particularly those who like "scary stories." Robby is an appealing character who tries to do what's right, even at the expense of his own family. The book does play to the stereotype of the long-suffering Irish mother and the drunk, abusive Irish father. Robby's mother makes excuses for the father's behavior, telling Robby not to hate his father, but rather to feel sorry for him and to pray for him. She tells her son that she can't leave his father, but Robby can when he's old enough. While this may offend out 21st century sensibilities, many women indeed were trapped in unhappy marriages during this time, with no feasible way out, especially since their husband controlled all the property.

Disclosure: Review copy provided by publisher. Display Comments Add a Comment

Blog: The Fourth Musketeer (Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags: adventure, 19th century, Add a tag

Recommended for ages 10 and up.

Benjamin has a happy life in 19th century Baltimore in his affluent family, with his own pony, and no worries other than planning a picnic with his pretty neighbor Jane. That is, until he is grabbed with a group of German immigrants and forced to work as part of the crew on the Ella Dawn, a decrepit oyster boat. The Captain, who rarely surfaces, is a cruel drunk, and the first mate, Plum, runs the ship with a heavy hand. They dub Ben "Little Gentleman" and laugh when he tells them his father is a wealthy lawyer.

Little did Ben know that the delicious oysters he and his family enjoyed at the holidays were likely to have been caught by a half-starved man or boy coerced into working on the oyster barges. The work was considered so awful that no one would do it for wages, so the men are locked into the hold each night until the oyster season is over. Although on the barge Ben no longer goes to school, he gets an education in life that he could never have imagined at home in Baltimore.

Conly writes in detail about the hard life the men on the barges faced, with long hours of backbreaking work and constant hunger. Yet in spite of the hard work and awful conditions, Ben develops a love of the sea, and his family and luxurious lifestyle seem only a distant memory. Will he be able to escape his bondage and return to his family? Or does he no longer want the conventional life of a lawyer that his family had planned for him?

Fans of adventure stories like Avi's The True Confessions of Charlotte Doyle are sure to enjoy this fast-paced, exciting tale of murder and adventure on the high seas. It's also a coming-of-age tale as Ben struggles to understand what his path in life should be. At 164 pages, this is a quick read that should appeal to reluctant readers as well as any young people looking for an action-filled adventure story.

View Next 1 Posts

Thank you, Margo. I love it when my books connect with readers--and librarians.