new posts in all blogs

Viewing: Blog Posts Tagged with: Bernstein, Most Recent at Top [Help]

Results 1 - 4 of 4

How to use this Page

You are viewing the most recent posts tagged with the words: Bernstein in the JacketFlap blog reader. What is a tag? Think of a tag as a keyword or category label. Tags can both help you find posts on JacketFlap.com as well as provide an easy way for you to "remember" and classify posts for later recall. Try adding a tag yourself by clicking "Add a tag" below a post's header. Scroll down through the list of Recent Posts in the left column and click on a post title that sounds interesting. You can view all posts from a specific blog by clicking the Blog name in the right column, or you can click a 'More Posts from this Blog' link in any individual post.

By: Alice,

on 8/12/2014

Blog:

OUPblog

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

Books,

Music,

Berkshires,

Gilbert and Sullivan,

bernstein,

Leonard Bernstein,

*Featured,

Theatre & Dance,

Carmen,

Arts & Leisure,

Adolph Green,

Betty Comden,

Bernstein Meets Broadway,

Carol J. Oja,

Collaborative Art in a Time of War,

Camp Onota,

Jerome Robbins,

Jewish summer camp,

onota,

elderly—recalled,

bernstein’s,

Add a tag

By Carol J. Oja

Rising to prominence at lightning speed during World War II, Leonard Bernstein quickly became one of the most famous musicians of all time, gaining notice as a conductor and composer of both classical works and musical theater. One day he was a recent Harvard graduate, struggling to earn a living in the music world. The next, he was on the front page of the New York Times for his stunning debut with the New York Philharmonic in November 1943. At twenty-five, Bernstein was the newly appointed assistant conductor of the orchestra, and he stepped in at the last minute to replace the eminent maestro Bruno Walter in a concert that was broadcast over the radio.

At the same time – and with the same blistering pace — Bernstein had two high-profile premieres in the theater: the ballet Fancy Free in April 1944, and the Broadway musical On the Town in December that same year. For both, he collaborated with the young choreographer Jerome Robbins, and the two men later became mega-famous for West Side Story in 1957. Added to that, the writers of the book and lyrics for On the Town were Bernstein’s close friends Betty Comden and Adolph Green, whose major celebrity came with the screenplay for Singin’ in the Rain in 1952.

So 1944 was a key year for Bernstein in the theater. Yet he already had considerable experience with theatrical productions, albeit with neighborhood kids in the Jewish community of Sharon, Massachusetts, south of Boston, where his parents had a summer home, and as a counselor at a Jewish summer camp in the Berkshires.

Some of these productions were charmingly outrageous, including a staging of Carmen in Sharon during the summer of 1934, when Bernstein was fifteen. Together with his male friend Dana Schnittken, Bernstein organized local teens in presenting an adaptation of Carmen in Yiddish, with the performers in drag. “Together we wrote a highly localized joke version of a highly abbreviated Carmen in drag, using just the hit tunes,” Bernstein later recalled in an interview with the BBC. “Dana played Micaela in a wig supplied by my father’s Hair Company—I’ll never forget his blonde tresses—and I sang Carmen in a red wig and a black mantilla and in a series of chiffon dresses borrowed from various neighbors on Lake Avenue, through which my underwear was showing. Don José was played by the love of my life, Beatrice Gordon. The bullfighter was played by a lady called Rose Schwartz.” Bernstein’s father, who was an immigrant to the United States, owned the Samuel J. Bernstein Hair Company in Boston, which not only prospered mightily during the Great Depression but also provided wigs for his son’s theatrical exploits.

The young Leonard’s summer performances also involved rollicking productions of operettas by Gilbert and Sullivan. In the summer of 1935, he directed The Mikado in Sharon. Bernstein sang the role of Nanki-Poo, and his eleven-year-old sister Shirley was Yum-Yum. Decades later, friends of Bernstein who were involved in that production—by then quite elderly—recalled going with the cast to a nearby Howard Johnson’s Restaurant to celebrate. After eating a hearty meal, they stole the silverware! Being upright young citizens, they quickly returned it.

In the summer of 1936, Bernstein and his buddies produced H.M.S. Pinafore. “I think the bane of my family’s existence was Gilbert and Sullivan, whose scores my sister Shirley and I would howl through from cover to cover,” Bernstein later reminisced to The Book of Knowledge.

As a culmination of this youthful activity, Bernstein produced The Pirates of Penzance during the summer of 1937, while he worked as the music counselor at Camp Onota in the Berkshires. His future collaborator Adolph Green was a visitor at the camp, and Green took the role of the Pirate King.

A photograph in the voluminous Bernstein Collection at the Library of Congress vividly evokes Bernstein’s experience at Camp Onota. There, the youthful Lenny stands next to a bandstand, conducting a rhythm band of even younger campers. This is clearly not a stage production. But there he is – an aspiring conductor, honing his craft in the balmy days of summer.

As it turned out, Bernstein’s transition from teenage artistic adventures to mature commercial success—from camp T-shirts to tux and tails—took place in a blink.

Carol J. Oja is William Powell Mason Professor of Music and American Studies at Harvard University. She is author of Bernstein Meets Broadway: Collaborative Art in a Time of War and Making Music Modern: New York in the 1920s (2000), winner of the Irving Lowens Book Award from the Society for American Music.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only music articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

The post The teenage exploits of a future celebrity appeared first on OUPblog.

By: Alice,

on 7/24/2014

Blog:

OUPblog

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

Books,

Music,

bernstein,

billie holiday,

Leonard Bernstein,

*Featured,

Theatre & Dance,

Arts & Leisure,

stuff”,

Bernstein Meets Broadway,

Carol J. Oja,

Collaborative Art in a Time of War,

Add a tag

When Leonard Bernstein first arrived in New York, he was unknown, much like the artists he worked with at the time, who would also gain international recognition. Bernstein Meets Broadway: Collaborative Art in a Time of War looks at the early days of Bernstein’s career during World War II, and is centered around the debut in 1944 of the Broadway musical On the Town and the ballet Fancy Free. This excerpt from the book describes the opening night of Fancy Free.

When the curtain rose on the first production of Fancy Free, the audience at the old Metropolitan Opera House did not hear a pit orchestra, which would have followed a long-established norm in ballet. Rather, a recorded vocal blues wafted from the stage. Those attending must have been caught by surprise, as they were drawn into a contemporary sound world. The song was “Big Stuff,” with music and lyrics by Bernstein. It had been conceived with the African American jazz singer Billie Holiday in mind, even though it ended up being recorded for the production by Bernstein’s sister, Shirley. At that early point in Bernstein’s career, he lacked the cultural and fiscal capital to hire anyone as famous as Holiday. The melody and piano accompaniment for “Big Stuff” contained bent notes and lilting rhythms basic to urban blues, and the lyrics summoned up the blues as an animate force, following a standard rhetorical mode for the genre:

So you cry, “What’s it about, Baby?”

You ask why the blues had to go and pick you.

Talk of going “down to the shore” vaguely referred to the sailors of Fancy Free, as the lyrics became sexually explicit:

So you go down to the shore, kid stuff.

Don’t you know there’s honey in store for you, Big Stuff?

Let’s take a ride in my gravy train;

The door’s open wide,

Come in from out of the rain.

“Big Stuff” spoke to youth in the audience by alluding to contemporary popular culture. It boldly injected an African American commercial idiom into a predominantly white high-art performance sphere, and its raunchiness enhanced the sexual provocations of Fancy Free. “Big Stuff” also blurred distinctions between acoustic and recorded sound. It marked Bernstein as a crossover composer, with the talent to write a pop song and the temerity to unveil it within a high-art context.

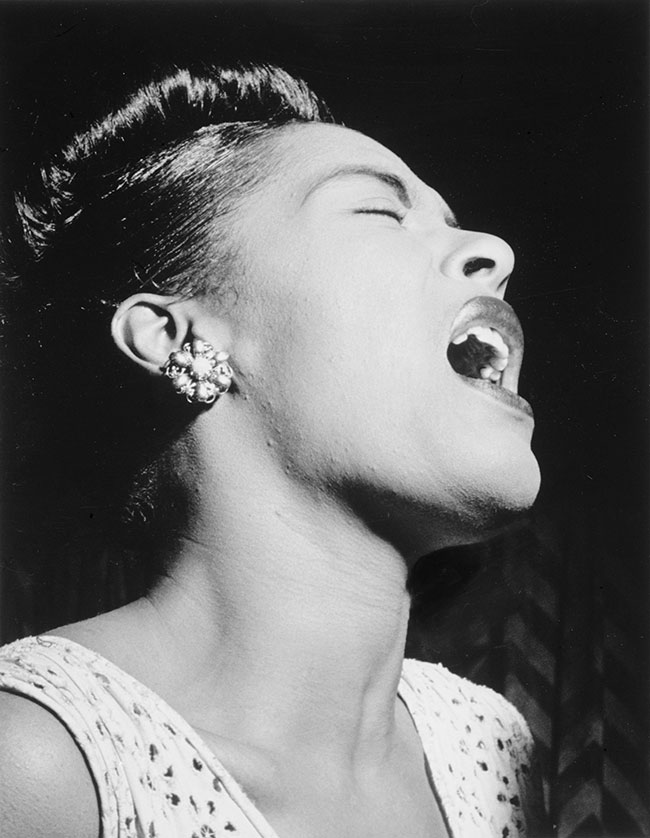

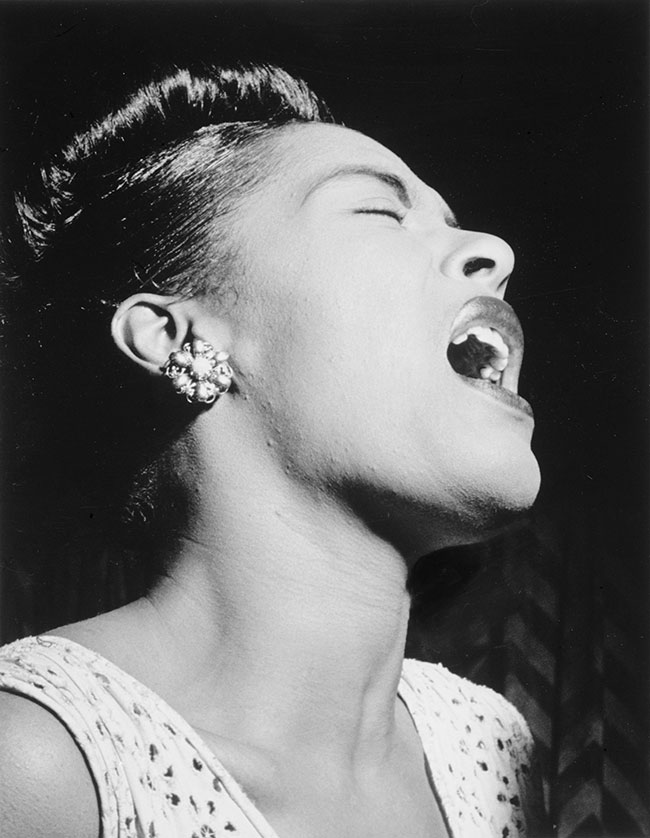

Billie Holiday by William P. Gottlieb, c. February 1947. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

Billie Holiday was “one of [Bernstein’s] idols,” according to Humphrey Burton. He admired her brilliance as a performer, and he was also sympathetic to her progressive politics. In 1939, Holiday first recorded “Strange Fruit,” a song about a lynching that became one of her signatures. With biracial and left-leaning roots, “Strange Fruit” was written by the white teacher and social activist Abel Meeropol. Holiday performed “Strange Fruit” nightly at Café Society, a club that enforced a progressive desegregationist agenda both onstage and in the audience. Those performances marked “the beginning of the civil rights movement,” recalled the famed record producer Ahmet Ertegun (founder of Atlantic Records). Barney Josephson, who ran Café Society, famously declared, “I wanted a club where blacks and whites worked together behind the footlights and sat together out front.”

Bernstein had experience on both sides of Café Society’s footlights. In the early 1940s, he performed there occasionally with The Revuers, and he played excerpts from The Cradle Will Rock in at least one evening session with Marc Blitzstein. Bernstein also hung out at the club with friends, including Judy Tuvim, Betty Comden, and Adolph Green, listening to the jazz pianist Teddy Wilson and boogie-woogie pianists Pete Johnson and Albert Ammons. Thus Bernstein had ample opportunities to witness the intentional “blurring of cultural categories, genres, and ethnic groups” that historian David Stowe has called the “dominant theme” of Café Society.

Robbins also had an affinity for the work of Billie Holiday. In the summer of 1940, he choreographed Holiday’s recording of “Strange Fruit” and performed it with the dancer Anita Alvarez at Camp Tamiment. “Strange Fruit was one of the most dramatic and heart-breaking dances I have ever seen—a masterpiece,” remembered Dorothy Bird, a dancer there that summer.

As a result of these experiences, the music of Billie Holiday had crossed the paths of both Robbins and Bernstein before “Big Stuff” opened their first ballet. While Billie Holiday’s voice was not heard the evening of Fancy Free’s premiere, only seven months passed before she recorded “Big Stuff” with the Toots Camarata Orchestra on November 8, 1944. The fact that Holiday made this recording so soon after the premiere of Fancy Free bore witness to the rapid rise of Bernstein’s clout within the music industry. Over the next two years, Holiday made six more recordings of “Big Stuff,” and when Bernstein issued the first recording of Fancy Free with the Ballet Theatre Orchestra in 1946, Holiday’s rendition of “Big Stuff” opened the disc. Both she and Bernstein recorded for the Decca label. Holiday recorded her final three takes of “Big Stuff” for Decca on March 13, 1946, and that label released Fancy Free the same year.

Musically, “Big Stuff” links closely to the worlds of George Gershwin and Harold Arlen, whose songs drew on African American idioms. Like some of the most beloved songs by these composers — whether Arlen’s “Stormy Weather” of 1933 or Gershwin’s “Summertime” of 1935 from Porgy and Bess – “Big Stuff” used a standard thirty-two-bar song form. With a tempo indication of “slow & blue,” “Big Stuff” has a lilting one-bar riff in the bass, a classic formulation for a jazzbased popular song of the day. The riff retains its shape throughout, as is also typical, while its internal pitch structure shifts in relation to the harmonic motion. Both the accompaniment and melody are drenched with signifiers of the blues, especially with chromatically altered third, fourth, sixth, and seventh scale degrees, and the overall downward motion of the melody is also characteristic of the blues, with a weighted sense of being ultimately earthbound.

Carol J. Oja is William Powell Mason Professor of Music and American Studies at Harvard University. She is author of Bernstein Meets Broadway: Collaborative Art in a Time of War and Making Music Modern: New York in the 1920s (2000), winner of the Irving Lowens Book Award from the Society for American Music.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to onyl music articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

The post Echoes of Billie Holiday in Fancy Free appeared first on OUPblog.

By: Rebecca,

on 5/28/2009

Blog:

OUPblog

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

Nixon,

Bernstein,

Phelps,

Frankel,

Hersh,

watergate,

Woodward,

New York Times,

Politics,

Current Events,

American History,

Smith,

A-Featured,

A-Editor's Picks,

Media,

Washington Post,

Gray,

Add a tag

Donald Ritchie, author of Reporting from Washington: The History of the Washington Press Corps, Our Constitution, and The Congress of the United States: A Student Companion, looks at The New York Times decision not to break the Watergate story. Ritchie, who has been Associate Historian of the United States Senate for more than three decades, reveals that it was a series of mistakes, not just one, that led to The Washington Post breaking the story. Ritchie’s book, Reporting from Washington, was also ahead of the pack, identifying Deep Throat as being in the FBI months before Mark Felt confessed.

Watergate is back in the news thanks to the recent confessions of a former New York Times reporter, Robert M. Smith, and his Washington bureau editor, Robert H. Phelps, about how they failed to report a hot tip on the Nixon administration’s involvement in the cover-up. Preparing to leave the paper in August 1972, to attend law school, Smith held a farewell lunch with acting FBI director L. Patrick Gray, who revealed that his agents had found evidence of “dirty tricks” being employed by the Nixon reelection campaign, leading to the top levels. Smith reported this to Phelps, but he was leaving on a month-long vacation and let the story drop. The rest of the media has relished reporting on how the Times let the political story of the century slip away.

Of course, the rest of the media–with the notable exception of the Washington Post– fumbled the Watergate scandal as well. Even at the Post, the story was almost the exclusive property of two green reporters from the Metro section. Those who covered the national news dismissed the idea of presidential involvement in the Watergate burglary as being highly implausible. Washington correspondents may not have liked Richard Nixon, but they respected his intelligence and held it inconceivable that he would jeopardize his presidency by bugging his faltering opposition.

Without detracting from Bob Woodward and Carl Bernstein’s assiduous reporting, we know now that their chief inside information was coming from the FBI’s deputy director, W. Mark Felt. He systematically leaked in order to prevent the White House from derailing the FBI’s investigation. The insights Felt provided the Post kept the story alive for months.

When the Watergate burglars were arraigned, it was initially seen as a local police story. Since the New York Times’ Washington bureau only covered federal courts, the Times buried a short report deep inside the next day’s paper, while the Washington Post put it on the front page. Max Frankel, the Times’ Washington bureau chief, discouraged his correspondents from pursing Watergate. “Not even my most cynical view of Nixon had allowed for his stupid behavior,” Frankel later lamented. It went on that way for the rest of 1972, with the Post running story after story, and the rest of the media sharing the Times’ reluctance. Further clouding the Washington bureau’s judgment was its condescending attitude toward the Washington Post, which the New Yorkers regarded as little more than a provincial paper in a government town–a step or two above Albany. Despite Woodward and Bernstein’s prodigious output during the summer of 1972, Frankel insisted that their reporting failed to measure up to his standards of reporting. Small wonder, then, that Robert Smith’s tip never made it into the “paper of record.”

The New York Times finally got a handle on Watergate when it hired the investigative reporter Seymour Hersh. In January 1973, Hersh scooped even Woodward and Bernstein by documenting how White House hush money had gone to the Watergate burglars. Reporters for other papers were developing their own leads and the rest of the pack piled on top. Ever since then–right up to the current revelations–Washington reporters have puzzled over why they missed the Watergate story for so long. The White House press corps came in for the harshest criticism, accused by former press secretary Bill Moyers of being “sheep with short attention spans.” But White House reporters, dependent on White House sources, were no more likely to uncover White House scandals than police reporters were to expose police graft. It took a couple of young, ambitious, local news reporters to think the unthinkable.

By: Rebecca,

on 11/24/2008

Blog:

OUPblog

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

Health,

A-Featured,

Harvard,

Medical Mondays,

drugs,

artemisinin,

Bernstein,

Chivian,

ethnobotany,

quinine,

Sustaining Life,

wormwood,

Add a tag

Eric Chivian, MD, is the founder and Director of the Center for Health and the Global Environment at Harvard Medical School. In 1980, he co-founded, with three other Harvard faculty members, International Physicians for the Prevention of Nuclear War, which won the 1985 Nobel Peace Prize. Aaron Bernstein, MD has been affiliated with the Center for Health and the Global Environment since 2001 and is currently a resident in the Boston Combined Residency in Pediatrics. Together they wrote Sustaining Life: How Human Health Depends on Biodiversity which presents a comprehensive review of how human medicines, biomedical research, the emergence and spread of infectious diseases, and the production of food all depend on biodiversity. In the excerpt below the authors look at how traditional medicine has led to some of our most important modern drugs.

Ethnobotany, that is, the scientific study of the use of plants by native cultures, including their use as medicines, can be said to have begun with Carl Linnaeus, who in the 1730s published Flora Lapponica, his detailed account of plant use by the Lappish, or Sami, people, living north of the Arctic Circle. These observations, like many made since then that draw on knowledge of the natural world gathered over many generations by indigenous peoples, have contributed significantly to the practice of medicine today.

The history of two modern pharmaceuticals—quinine and artemisinin serve to illustrate our enormous debt to traditional medical healers.

Quinine

The isolation of the antimalarial drug quinine from the bark of cinchona trees (e.g., Cinchona officialinis) was accomplished by the French chemists Pierre- Joseph Pelletier and Joseph-Bienaimé Caventou in 1820. The bark had long been used by indigenous peoples in the Amazon region for the treatment of fevers. Spanish  Jesuit missionaries, after the conquest of the Inca Empire in Peru in the late sixteenth and early seventeenth century, learned of this use from the natives and found that the bark was effective in preventing and treating malaria. They brought this knowledge, along with the bark, back to Europe, where it became widely used and was often referred to as “Peruvian bark.” With quinine as the model, chemists subsequently synthesized the antimalarial drugs chloroquine and mefloquine, and they have continued to modify the basic structure of quinine to produce even more effective agents, such as the new antimalarial bulaquine.

Jesuit missionaries, after the conquest of the Inca Empire in Peru in the late sixteenth and early seventeenth century, learned of this use from the natives and found that the bark was effective in preventing and treating malaria. They brought this knowledge, along with the bark, back to Europe, where it became widely used and was often referred to as “Peruvian bark.” With quinine as the model, chemists subsequently synthesized the antimalarial drugs chloroquine and mefloquine, and they have continued to modify the basic structure of quinine to produce even more effective agents, such as the new antimalarial bulaquine.

Artemisinin

The Sweet Wormwood plant (Artemesia annua) was also used as a treatment for fevers in China for more than 2,000 years (it is called qing hao in Chinese), but it was not until 1972 that the active compound artemisinin (qing hao su, which means the active principle of qing hao) was extracted and later identified as a potent antimalarial drug by Chinese scientists. This effort was part of a systematic examination at that time of indigenous plants in China as sources of new medicines. More soluble derivatives, artemether, artether, and artemotil, have been developed in recent years. These medicines, in combination with other antimalarials such as mefloquine, have proved highly effective in treating malaria, particularly the most deadly form caused by Plasmodium falciparum (see chapter 7 for a further discussion of malaria), which has become increasingly resistant to the first-line treatments chloroquine and sulfadoxine-pyrimethamine—in Asia, South and Central America, and Africa. Given that malaria, despite intensive efforts by the world community, continues to kill between one and three million people each year, approximately three-fourths of whom are African children, and to cripple economies around the world, the importance of artemisinin and other effective antimalarials cannot be overstated.

Another possible use of artemisinin is in the treatment of cancer. Its antimalarial activity is thought to be due to its interaction with iron, present in very high concentrations in the malarial parasite. Since some cancer cells, particularly leukemia cells, also have high iron concentrations, they may also be killed by artemisinin, as has been demonstrated in some initial studies with cancer cells in tissue culture. The potential of artemisinin and its derivatives as cancer chemotherapeutic agents is being actively investigated in a variety of anticancer screens.

The combination of a high demand for artemisinin-based antimalarials and limited commercial-scale production of Artemesia annua (in only a few locales in China and Vietnam) has left artemisinin-based therapies in short supply. The World Health Organization has stepped in to develop a plan to bolster production.

One possible solution to the supply problem may come from biotechnology. Scientists in California have recently produced the base structure of the chemical artemisinin in the bacterium Escherichia coli, and in yeast (Saccharomyces cerevisiae), by transferring the necessary genes from Artemisia annua into these microbes. For E. coli or yeast to become a viable source for artemisinin, the base structure would need to be modified, and the entire process would have to be scaled up to achieve commercial production levels.

Traditional medicine, as practiced by indigenous people today, relies on its own version of “clinical trials,” where natural products continue to be used only if they have been shown to be effective. These trials may take place over very long periods of time, sometimes over hundreds of years by generations of healers, and they lead to a vast and detailed knowledge of the medicinal properties of many natural substances. That is why many believe there is such enormous potential for finding new medicines among those used by traditional healers.

But there are also problems in using these leads for drug discovery. For one, there is the problem of diagnosis. In the absence of diagnostic tools such as blood tests, X-rays, MRIs, and invasive techniques such as surgery, traditional healers must rely largely on a patient’s history, on the physical exam, and on the external manifestations of disease, all of which can be unreliable. Superstition may also prevent accurate diagnosis and, along with the placebo effect, cloud objective evaluation of the success of treatment. Furthermore, some diseases, for example, those involving the elderly, such as Alzheimer’s and most cancers, may be rare in some indigenous populations where life expectancy is short. Finally, knowledge may or may not have been faithfully transcribed from one generation to the next. Traditional medical practices in several parts of Asia, including China, Japan, Korea, and India, have been recorded in great detail over the centuries in written texts, in contrast to those in some other parts of the world, such as among South American Indians, where the passage of knowledge has been primarily by oral means. While these oral traditions may reflect very careful trials and observations, they are prone to errors as a result of unreliable transmission and anecdotal reports.

Nevertheless, indigenous healers have been critically important in the discovery of many new drugs. One study demonstrated that of 119 drugs (derived from some ninety plant species) currently in use in one or more countries, almost three-quarters were discovered by extracting the active chemicals from plants used in traditional medicines.

Tragically, traditional healers now face a double threat—both from the loss of biodiversity that depletes the natural sources that make up their pharmacopoeia, and from encroachment by the outside world that may wipe out their cultures. In the first three-quarters of the twentieth century, more than ninety tribes have become “extinct” in Brazil alone. Scientists are racing to record the secrets these native healers hold before they and the plants and other species they use are gone.

Aaron Bernstein’s recent article in the Journal of the American Medical Association (http://jama.ama-assn.org/) is also very illuminating.

FezNJ