By Jim Cullen

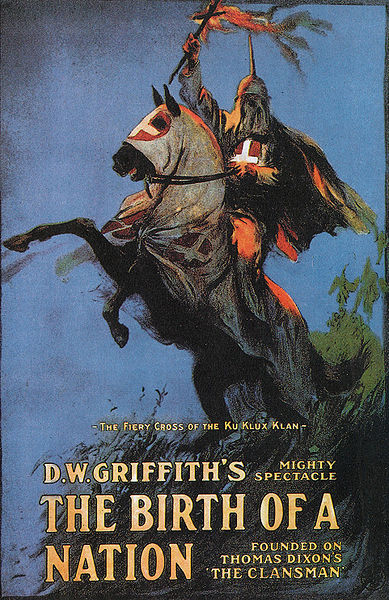

Today represents a red letter day — and a black mark – for US cultural history. Exactly 98 years ago, D.W. Griffith’s Birth of a Nation premiered in Los Angeles. American cinema has been decisively shaped, and shadowed, by the massive legacy of this film.

D.W. Griffith (1875-1948) was one of the more contradictory artists the United States has produced. Deeply Victorian in his social outlook, he was nevertheless on the leading edge of modernity in his aesthetics. A committed moralist in his cinematic ideology, he was also a shameless huckster in promoting his movies. And a self-avowed pacifist, he produced a piece of work that incited violence and celebrated the most damaging insurrection in American history.

D.W. Griffith (1875-1948) was one of the more contradictory artists the United States has produced. Deeply Victorian in his social outlook, he was nevertheless on the leading edge of modernity in his aesthetics. A committed moralist in his cinematic ideology, he was also a shameless huckster in promoting his movies. And a self-avowed pacifist, he produced a piece of work that incited violence and celebrated the most damaging insurrection in American history.

The source material for Birth of a Nation came from two novels, The Leopard’s Spots: A Romance of the White Man’s Burden (1902) and The Clansman: An Historical Romance of the Ku Klux Klan (1905), both written by Griffith’s Johns Hopkins classmate, Thomas Dixon. Dixon drew on the common-sense version of history he imbibed from his unreconstructed Confederate forebears. According to this master narrative, the Civil War was as a gallant but failed bid for independence, followed by vindictive Yankee occupation and eventual redemption secured with the help of organizations like the Klan.

But Dixon’s fiction, and the subsequent screenplay (by Griffith and Frank E. Woods), was a literal and figurative romance of reconciliation. The movie dramatizes the relationships between two (related) families, the Camerons of South Carolina and the Stonemans of Pennsylvania. The evil patriarch of the latter is Austin Stoneman, a Congressman with a limp very obviously patterned on the real-life Thaddeus Stevens. In the aftermath of the Civil War, Stevens comes, Carpetbagger-style, and uses a brutish black minion, Silas Lynch(!), whose horrifying sexual machinations focused, ironically and naturally, on Stoneman’s own daughter are only arrested by at the last minute, thanks to the arrival of the Klan in a dramatic finale that has lost none of its excitement even in an age of computer-generated imagery.

Historians agree that Griffith, a former actor who directed hundreds of short films in the years preceding Birth of a Nation, was not a cinematic pioneer along the lines of Edwin S. Porter, whose 1903 proto-Western The Great Train Robbery virtually invented modern visual grammar. Instead, Griffith’s genius was three-fold. First, he absorbed and codified a series of techniques, among them close-ups, fadeouts, and long shots, into a distinctive visual signature. Second, he boldly made Birth of a Nation on an unprecedented scale in terms of length, the size of the production, and his ambition to re-create past events (“history with lightning,” in the words of another classmate, Woodrow Wilson, who screened the film at the White House). Finally, in the way the movie was financed, released and promoted, Griffith transformed what had been a disreputable working-class medium and staked its power as a source of genuine artistic achievement. Even now, it’s hard not to be awed by the intensity of Griffith’s recreation of Civil War battles or his re-enactments of events like the assassination of Abraham Lincoln.

But Birth of a Nation was a source of instant controversy. Griffith may have thought he was simply projecting common sense, but a broad national audience, some of which had lived through the Civil War, did not necessarily agree. The film’s release also coincided with the beginnings of African American political mobilization. As Melvyn Stokes shows in his elegant 2009 book D.W. Griffith’s Birth of a Nation, the film’s promoters and its critics alike found the controversy surrounding it curiously symbiotic, as moviegoers flocked to see what the fuss was about and the fledgling National Association for the Advancement of Colored People used the film’s notoriety to build its membership ranks.

Birth of a Nation never escaped from the original shadows that clouded its reception. Later films like Gone with the Wind (1939), which shared much of its political outlook, nevertheless went to great lengths to sidestep controversy. (The Klan is only alluded to as “a political meeting” rather than depicted the way it was in Margaret Mitchell’s 1936 novel.) Today Birth is largely an academic curio, typically viewed in settings where its racism looms over any aesthetic or other assessment.

In a number of respects, Steven Spielberg’s new film Lincoln is a repudiation of Griffith. In Birth, Lincoln is a martyr whose gentle approach to his adversaries is tragically severed with his death. But in Lincoln he’s the determined champion of emancipation, willing to prosecute the war fully until freedom is secure. The Stevens character of Lincoln, played by Tommy Lee Jones, is not quite the hero. But his radical abolitionism is at least respected, and the very thing that tarred him in Birth — having a secret black mistress — here becomes a badge of honor. Rarely do the rhythms of history oscillate so sharply. Griffith would no doubt be bemused. But he could take such satisfaction in the way his work has reverberated across time.

For Jim Cullen’s selection of films all history and film buffs should see, watch his video syllabus.

Click here to view the embedded video.

Jim Cullen teaches history at the Ethical Culture Fieldston School in New York City. He is the author of Sensing the Past: Hollywood Stars and Historical Visions (December 2012), The American Dream: A Short History of an Idea that Shaped a Nation, and other books. Cullen is also a book review editor at the History News Network. Read his previous OUPblog posts.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only TV and film articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Image credit: Birth of a Nation film poster, 1915, public domain in Wikimedia Commons.

The post The strange career of Birth of a Nation appeared first on OUPblog.

Tonto Fielding was slighted by the Oscar Committee this year when his silent film, “The Treasonist,” was overlooked in favor of “The Artist.”

In fact, it is clear that I started the silent film revival, since I had been raising funds for my film’s production for the past twenty years. Clearly, it was my idea first. The Oscar committee informed me that my little film was turned down, because it had already been rejected at every film festival I had submitted it to, reciting some stupid rule about redundancy.

A young Napoleon Bonaparte, who is also played by Tonto Fielding, is portrayed as a poor and pretentious social climber, who narrowly escapes an adulterous scandal by declaring that it was done in the defense of Julia of Corsica.

Obviously, what was lost on the Academy, was that my portrayal was based on the traditions of abstract mime, where on the surface it appears that there is no central plot or character. This allows the audience to creatively formulate its own idea on the subject. Also lost on them, was the artistic inclusion of performing cows, dancing horses, geese, camels, llama's and happy dogs. This represented that the gossipers were completely without honor, and that everybody is flawed. Goodness does not depend on formal propriety and external sentimentalism, but lies deep within.

I guess I’ll have to go straight to DVD on this one, pending funding.

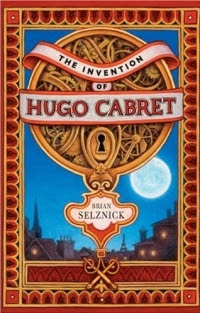

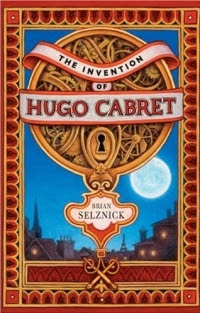

The Invention of Hugo Cabret

Author/Illustrator: Brian Selznick

Publisher: Scholastic

ISBN-10: 0439813786

ISBN-13: 978-0439813785

One word. MASTERPIECE!

The Invention of Hugo Cabret is an incredible book, the like of which I have never seen before. It’s a decadent visual treat as well as a gripping and wonderful story. It falls into its own category of part graphic novel, part novel, part cinema, part picture book with the occasional still of silent movies thrown into the mix.

The Invention of Hugo Cabret is the story of a young boy who lives in a train station in 1930’s Paris. His father, a clockmaker, died in a museum fire under mysterious circumstances and Hugo went to live with his drunken uncle, who had a job setting all the giant clocks in the station. Months ago, Hugo's uncle went out drinking and never came back. Frightened that he would be discovered and taken to an orphanage, Hugo has continued his uncle's job, allowing the paychecks to pile up living by stealing food from the various vendors in the train station.

He also steals mechanical parts from a toymaker. Hugo found an automaton in the ashes of the museum fire that killed his father and is determined to bring it to life, thinking that somehow, someway it will bring his father back since his father was quite obsessed with it before he died. Hugo gets caught stealing a toy mouse and becomes involved with the mysterious toymaker and his ward Isabel. The plot gets more and more intricate as it goes along and the mystery deepens until its marvelous ending. The great storytelling in this book doesn’t just rely on the pictures or artwork, rather each both text and art blend together to tell you an amazing tale. Each compliments the other and each balances each other out.

Each page takes you deeper into the mystery, tells more about the history of silent film and of one of its pioneer’s Georges Melies and his 1902 masterpiece, A Trip to the Moon. Selznick gives quite a bit of history of both automata and Georges Melies and gets the reader wanting more. Luckily, he includes lists of places to find out more as an appendix to the book. The book is huge and may be a little daunting for children or adults when they first see the size of it, but push, shove, do whatever you have to do to get them to open that first page because then, you’re hooked.

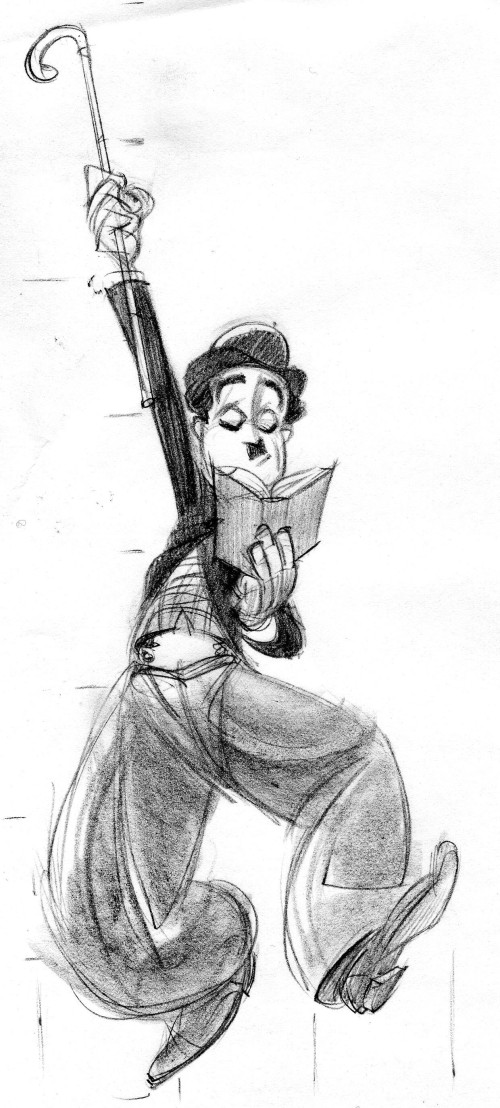

The book reminds me of a comic or a flipbook in that it has quite long sections of black and white sequential art telling the story without text. The illustrations in that art are gorgeous. They’re all done in these amazing pencil drawings that look like charcoal sketches and the detail is sublime.

The faces, especially the eyes are mesmerizing in their depth, beauty and seem stunningly lifelike yet with the haunting quality of a dream. The silent movie stills along with archival photographs of the era contribute to the dreamlike, silent film feels of the book. I loved how pages mimicked the pan of a camera and how drawings are set on black background to get that feel of old photographs or stills. It’s pure wonderful genius!

For more info on the book look here.

Word has it that book has been optioned by Warner Brothers and that Martin Scorcese has potentially signed on to direct the film.

I've been curious about this ever since I heard Scorsese had signed on to direct it ... It does indeed like a masterpiece, so I'm gonna see if it's at my local library .. thanks for the heads up!