Happy Leap Day! I was joking with Bookman this morning that anything we do today will have no consequences since the day doesn’t really exist. Now that I think about it though, I wonder if consequences just take longer, like they catch up with you in four years on the next Leap Day? Can you imagine gorging on chocolate and then in four years suddenly not be able to button your pants? Ha! It’s kind of funny but also not.

There is a great article at Popular Mechanics of all places about How the Humble Index Card Foresaw the Internet. Did you know the index card was invented by Carl Linnaeus? He came up with the brilliant idea while working on his taxonomies.

Waldo relaxing on top of my card cat-alog

Then during the French Revolution, French libraries began using index cards to catalog their collections. Of course Melvil Dewey then ran with the idea and used index cards to create a card catalog system that served us well for a very long time. I used to love browsing card catalogs. I am really lucky to have some old cabinets in my house. I use them for storing seed packets, knitting needles, sock yarn, fountain pen ink, hair clips and other odds and ends. I love my card catalog so much!

In 1895 two crazy Belgians set out to create their own “search engine” by using an even more detailed system than Dewey’s and millions of index cards that filled 15,ooo catalog drawers. One of the pair, Paul Otlet, wrote a book about the project in 1935 called Monde in which he envisioned all the information one day being digitized because the card database was essentially unsustainable at large scales.

And now we have the internet, a ginormous collection of databases and indices, a card catalog of unimaginable proportions. When you consider the internet as something that evolved from index cards it really boggles the mind.

I love, love, love index cards even though I hardly use them any longer. I love them so much I want to have a reason to use them but computers are so darn handy these days I go digital before I consider analog. But I keep a stash ready for when a project comes up that begs to be organized on index cards rather than my computer. One of these days there will be something and Bookman will come home to find the living room floor covered in cards and me happily shuffling them around while humming a happy song.

Filed under:

Technology Tagged:

card catalogs,

Carl Linnaeus,

index cards rock,

Melvil Dewey,

Paul Otlet

As soon as humanity began its quest for knowledge, people have also attempted to organize that knowledge. From the invention of writing to the abacus, from medieval manuscripts to modern paperbacks, from microfiche to the Internet, our attempt to understand the world — and catalog it in an orderly fashion with dictionaries, encyclopedias, libraries, and databases — has evolved with new technologies. One man on the quest for order was innovator, idealist, and scientist Paul Otlet, who is the subject of the new book Cataloging the World. We spoke to author Alex Wright about his research process, Paul Otlet’s foresight into the future of global information networks, and Otlet’s place in the history of science and technology.

What most surprised you when researching Paul Otlet?

Paul Otlet was a source of continual surprise to me. I went into this project with a decent understanding of his achievements as an information scientist (or “documentalist,” as he would have said), but I didn’t fully grasp the full scope of his ambitions. For example, his commitment to progressive social causes, his involvement in the creation of the League of Nations, or his decades-long dream of building a vast World City to serve as the political and intellectual hub of a new post-national world order. His ambitions went well beyond the problem of organizing information. Ultimately, he dreamed of reorganizing the entire world.

What misconceptions exist regarding Paul Otlet and the story of the creation of the World Wide Web itself?

It’s temptingly easy to overstate Otlet’s importance. Despite his remarkable foresight about the possibilities of networks, he did not “invent” the World Wide Web. That credit rightly goes to Tim Berners-Lee and his partner (another oft-overlooked Belgian) Robert Cailliau. While Otlet’s most visionary work describes a global network of “electric telescopes” displaying text, graphics, audio, and video files retrieved from all over the world, he never actually built such a system. Nor did the framework he proposed involve any form of machine computation. Nonetheless, Otlet’s ideas anticipated the eventual development of hypertext information retrieval systems. And while there is no direct paper trail linking him to the acknowledged forebears of the Web (like Vannevar Bush, Douglas Engelbart, and Ted Nelson), there is tantalizing circumstantial evidence that Otlet’s ideas were clearly “in the air” and influencing an increasingly public dialogue about the problem of information overload – the same cultural petri dish in which the post-war Anglo-American vision of a global information network began to emerge.

What was the most challenging part of your research?

The sheer size of Otlet’s archives–over 1,000 boxes of papers, journals, and rough notes, much of it handwritten and difficult to decipher–presented a formidable challenge in trying to determine where to focus my research efforts. Fortunately the staff of the Mundaneum in Mons, Belgium, supported me every step of the way, helping me wade through the material and directing my attention towards his most salient work. Otlet’s adolescent diaries posed a particularly thorny challenge. On the one hand they offer a fascinating portrait of a bright but tormented teenager who by age 15 was already dreaming of organizing the world’s information. But his handwriting is all but illegible for long stretches. Even an accomplished French translator like my dear friend (and fellow Oxford author) Mary Ann Caws, struggled to help me decipher his nineteenth-century Wallonian adolescent chicken scratch. Chapter Two wouldn’t have been the same without her!

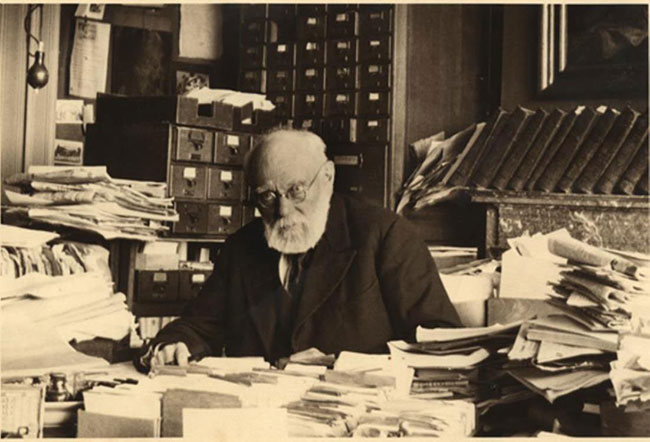

Photograph of Paul Otlet, circa 1939. Reproduced with permission of the Mundaneum, Mons, Belgium.

How do you hope this new knowledge of Otlet will influence the ways in which people view the Internet and information sites like Wikipedia?

I hope that it can cast at least a sliver of fresh light on our understanding of the evolution of networked information spaces. For all its similarities to the web, Otlet’s vision differed dramatically in several key respects, and points to several provocative roads not taken. Most importantly, he envisioned his web as a highly structured environment, with a complex semantic markup called the Universal Decimal Classification. An Otletian version of Wikipedia would almost certainly involve a more hierarchical and interlinked presentation of concepts (as opposed to the flat and relatively shallow structure of the current Wikipedia). Otlet’s work offers us something much more akin in spirit to the Semantic Web or Linked Data initiative: a powerful, tightly controlled system intended to help people make sense of complex information spaces.

Can you explain more about Otlet’s idea of “electronic telescopes” – whether they were feasible/possible, and to what extent they led to the creation of networks (as opposed to foreshadowing them)?

One early reviewer of the manuscript took issue with my characterization of Otlet’s “electric telescopes” as a kind of computer, but I’ll stand by that characterization. While the device he described may not fit the dictionary definition of a computer as a “programmable electronic device” – Otlet never wrote about programming per se – I would take the Wittgensteinian position that a word is defined by its use. By that standard, Otlet’s “electric telescope” constitutes what most of us would likely describe as a computer: a connected device for retrieving information over a network. As to whether it was technically feasible – that’s a trickier question. Otlet certainly never built one, but he was writing at a time when the television was first starting to look like a viable technology. Couple that with the emergence of radio, telephone, and telegraphs – not to mention new storage technologies like microfilm and even rudimentary fax machines – and the notion of an electric telescope may not seem so far-fetched after all.

What sorts of innovations would might have emerged from the Mundaneum – the institution at the center of Otlet’s “World City” – had it not been destroyed by the Nazis?

While the Nazi invasion signalled the death knell for Otlet’s project, it’s worth noting that the Belgian government had largely withdrawn its support a few years earlier. By 1940 many people already saw Otlet as a relic of another time, an old man harboring implausible dreams of international peace and Universal Truth. But Otlet and a smaller but committed team of staff soldiered on, undeterred, cataloging the vast collection that remained intact behind closed doors in Brussels’ Parc du Cinquantenaire. When the Nazis came, they cleared out the contents of the Palais Mondial, destroying over 70 tons worth of material, and making room for an exhibition of Third Reich art. Otlet’s productive career effectively came to an end, and he died a few years later in 1944.

It’s impossible to say quite how things might have turned out differently. But one notable difference between Otlet’s web and today’s version is the near-total absence of private enterprise – a vision that stands in stark contrast to today’s Internet, dominated as it is by a handful of powerful corporations.

Otlet’s Brussels headquarters stood almost right across the street from the present-day office of another outfit trying to organize and catalog the world’s information: Google.

Alex Wright is a professor of interaction design at the School of Visual Arts and a regular contributor to The New York Times. He is the author of Cataloging the World: Paul Otlet and the Birth of the Information Age and Glut: Mastering Information through the Ages.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only technology articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

The post Paul Otlet, Google, Wikipedia, and cataloging the world appeared first on OUPblog.