new posts in all blogs

Viewing: Blog Posts Tagged with: Susan Price, Most Recent at Top [Help]

Results 1 - 6 of 6

How to use this Page

You are viewing the most recent posts tagged with the words: Susan Price in the JacketFlap blog reader. What is a tag? Think of a tag as a keyword or category label. Tags can both help you find posts on JacketFlap.com as well as provide an easy way for you to "remember" and classify posts for later recall. Try adding a tag yourself by clicking "Add a tag" below a post's header. Scroll down through the list of Recent Posts in the left column and click on a post title that sounds interesting. You can view all posts from a specific blog by clicking the Blog name in the right column, or you can click a 'More Posts from this Blog' link in any individual post.

By: Barbara Fisher,

on 10/18/2014

Blog:

March House Books Blog

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

Books,

Enid Blyton,

Susan Price,

Angela Brazil,

Compton Mackenzie,

Frances Cowen,

Pat Smythe,

Patricia Leitch,

W. E. Johns,

Add a tag

I'm beginning to wonder if my perfect job isn't the job for me. Don’t get me wrong I love every minute of it, but it hardly pays the bills. It’s my own fault. I spend more time reading than cataloguing but how can I resist when so many beautiful books pass through my hands. I somehow have to limit the number I read, after all I am supposed to be listing them for sale, not keeping them for my own pleasure.

In How to Read a Novel (Profile Books, 2006), John Sutherland, suggests one trick for intelligent book browsing: turn to page 69 and read it. If you like what you read there, read the whole book. Sutherland in fact credits Marshall McLuhan, guru-author of Guttenberg Galaxy: The Making of Typographical Man (University of Toronto Press, 1962) as the originator of this test.

With that in mind, I've picked eight random paragraphs from page 69 of eight books recently catalogued. I've no idea what to expect, but here goes;

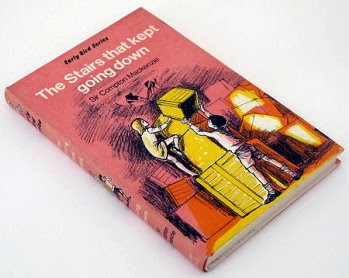

Compton Mackenzie The stairs that kept going down; Have you ever had a nightmare when you were being chased through a dark passage by something or somebody, and when your knees kept getting more and more jellified? If you have you will know what William and Winifred were feeling like when they made their way back along the dark bricked passage, trying to run on tip toes and trying not even to breathe too loudly. And this was not a nightmare from which they would wake up, frightened of course, but still in the safety of their own beds. This was real, horribly, hopelessly, hauntingly real.

Capt. W. E. Johns Biggles in the cruise of the Condor; They strolled a few yards farther on, and suddenly Biggles paused in his stride and nudged Smyth in the ribs. Just beyond the jail was an open yard filled with wooden cases and several piles of dried palm fronds, which were evidently used as packing for the stacks of adobe bricks that stood at the far end of the yard. Biggles eyed it reflectively, and then, followed by Smythe, crossed over to it. A flimsy fence with a gate, which they quickly ascertained was locked, separated the yard from the road. He turned as a car pulled up a short distance away and a man alighted, lit a cigarette, and then disappeared into a private house. Biggles strolled idly towards the car, his eyes running over it swiftly. It was a Ford, and he noted the spare tin of petrol fastened to the running-board.

They stared up into the trees, amazed to see green leaves waving above them. Then they turned their heads and saw one another. In a flash they remembered everything. “Couldn’t think where I was,” said Jack, and sat up. “Oh, Kiki, it’s you on my middle, is it? Do get off. Here, have some sunflower seeds and keep quiet, or you’ll wake the girls.” He put his hand in his pocket and took out some of the flat seeds that Kiki loved. She flew up to the bough above, cracking two in her beak. The boys began to talk quietly, so as not to disturb the girls, who were still sleeping peacefully.

Patricia Leitch Highland Pony Trek; “To be quite frank with you,” the Colonel said, “I’d rather see my land barred to everyone. It’s high time this maniac was caught and brought to justice. Been going on for a year now. A sheep here and a sheep there. All the time suspicion growing, innocent men being accused and ill feeling all round.”

Pat Smythe The Three Jays on holiday: From Avignon to the University town of Aix en Provence, the children gamely fought a losing battle against going to sleep. Darcy covered the last lap of the journey in record time, as he wanted to see a flying friend of his who lived in Aix and perhaps get him to have dinner with them. Jane, was encouraging his use of a few French words, in fact the four of them had a competition as to who could make the most French sounding sentence.

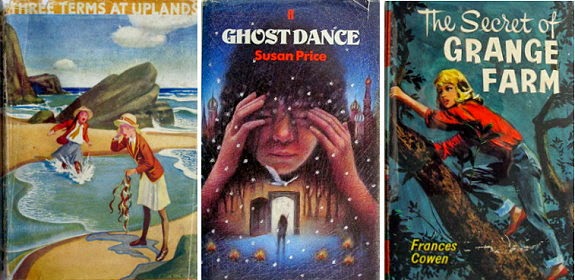

Angela Brazil Three terms at Uplands: Time wore away, and at last came the eventful day when the two male members of the family started for the north. Claire, having waved a farewell to their taxi from the gate, returned to the house feeling decidedly flat. There seemed nothing particular to do. Her own packing was finished. She wandered about during the morning, and after dinner she decided to go and say good-bye to Honor Marshall, a girl who lived in a road near. She found her friend seated in a summer-house in the garden, and began to expatiate upon her own prospects at Uplands.

Susan Price Ghost dance; The wind had dropped and it was a silent land she skimmed over, but with her shaman’s training she heard every sound there was: the hiss of her skies on the snow, the whining of the wind in the trees and the sharp knock of one branch against another, the sudden scream of a fox. She moved always towards the south, which she knew from the stars. Once, when the stars were covered, she asked the way of a blue fox, calling out, “Elder sister – which way to the city, the Czar’s city in the South?”

Frances Cowen The secret of Grange Farm; Now for the quarry. She stood in the road taking her bearings. It lay, she remembered, due east from the farm but only about ten minutes’ walk through the fields. In fact the quarry was on their land, and, in the old forgotten days, when Napoleon had threatened our shores, the owners of the farm had made quite an income out of it. Nicky had taken her there and helped her down to the old workings, chipped off part of the chalk, and shown her the fossils embedded in it. She decided to by-pass the farm, and to cross the fields, and so down to the cup-like valley which formed the quarry. Presently she found it so dark that she had to use her torch to find the little track she only just remembered, but, even as she did so, a faint flow showed in the sky as the moon rose slowly beyond scudding clouds.

So there you have it, some of the language is a little old fashioned, but I still want to read them all! How about you, if you’re not convinced, why not try a similar experiment, I would love to hear how you get on…

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Just before I go – do you remember the

Lottie Holiday Adventure StoryWriting Competition as featured on my blog in August? Four-year-old Evie from Perth, Western Australia wrote a quirky and adventurous tale about the discovery of a T-Rex dinosaur bone. The story was selected ahead of other entrants from countries including the USA, UK, Australia and UAE, and wins Evie a selection of ten books from the Lottie Pinterest folder ‘

Great Books for Girls’ (that boys can read too!), in addition to exclusive new Lottie products before they hit the shelves. Well done Evie!

One last thing, while I was looking around the Internet for clues about how others decide on their next read I came across this little pearl of wisdom written by

Nancy Pearl (sorry I couldn’t resist the pun!) – “One of my strongest beliefs is that no one should ever finish a book they’re not enjoying. Reading should be a joy. So, you can all apply my Rule of Fifty to your reading list. Give a book fifty pages if you’re under fifty years old. If you don’t like it, give it away, return it, whatever and then read something else. If you’re over fifty, subtract your age from 100 and that’s how many pages you should read …"

You know what that means, right? When you turn one hundred, you can judge a book by its cover.

Or, HOW TO PUT IT INTO BOOK WORDS.

As promised, I have cudgelled the brains over my student's question: How do you know what parts to rewrite? How do you know what words to change?

There are, I've concluded, two levels to rewriting: the big and the small.

The big takes in the whole of the book or story – never mind this or that word, does the whole thing work?

The small concentrates on words, sentences, paragraphs at most.

So, to begin small...

One of the most useful pieces of advice I ever came across was: Read your work aloud. It's a good idea to train yourself to hear a voice speaking the words in your head, even if you're reading or writing silently. This helps you to 'hear' the rhythms and stresses even as you invent the words - but it doesn't replace reading aloud.

Feeling your lips, tongue and throat shaping the words you've written, and hearing them, forces you to concentrate on every syllable, on rhythms, and on the sense. Reading by eye alone, you can skim through sentences, and even whole paragraphs if you're a very fluent reader (as writers tend to be). You can miss the small details of sound.

But words are, ultimately, meant to be spoken, not read. Poetry, as a poet once told me, is rhythm, not rhyme – and rhythm is sound.

But, when I rewrite, what am I listening for? How do I know which words to change?

Well, I consider if my words are easy to say, and pleasing to hear. The twelfth Leith Policeman dismisseth us. Beware of such jaw-breakers. What the eye reads easily may be a clog to the tongue – and I want that talking-book deal. So if I catch myself writing a tongue-twister, I rewrite it.

I'm on the listen-out for repeated sounds that jar. 'My keel coursed cruel care-halls - ' The Anglo-Saxons were keen on alliteration, and if consciously done for effect, it can be wonderful. But if I've repeated sounds through carelessness, and it's spoiling the rhythmn or sound, I change the wording

Are the words I've chosen the best ones for the job I wanted them to do? English is crammed with words that are close in meaning, but have their own nuances, weights, textures and colours. 'Amble' has a clumsier and more endearing sound than 'stroll'. 'Lope' is quite different from either. 'Smirk' has very different connotations from 'smile' or 'giggle'. Is there another word that's a closer fit for my meaning? That means the same, but has a better sound or stress for that sentence? Or has a sound that better fits the sense?

Do the sentences have a good natural rhythm? Reading them aloud makes this obvious. Am I running out of breath before reaching the end of the sentence, or the next natural pause? Does the sentence have the natural swing of speech's rise and fall? When I read it aloud, does the stress fall on the most important words – the words I really want people to hear? If the answers are 'no', then shorten the sentence, or divide it into two; change the word order, or find other words.

But having said all this about making a sentence easy to read, sometimes I want to make a sentence clumsy or difficult. If I'm describing drudgery, then I want the words I use to be slow, awkward, clumsy, tired. I might want the sound and rhythmn of my words to reflect the sleek quickness, the harshness or the cold of their sense. If what I've written doesn't do that, I try to find words that do.

A frequent consideration is whether the phrase I've used is a cliché – a phrase too over-used and stale to make the reader stop and think about the sense. It isn't easy to avoid cliches, and I am certainly guilty of using them often. For one thing, they're often true – as white as snow, as cold as ice. But I am honour bound to try. So I give the brains another pummel, and see if I can come up with something fresher.

Finally, I check if I mean what I've said. Words can get away from you. A friend of mine, a teacher, once read in a pupil's exercise book: 'I was lying on the settee watching the telly eating peanuts.' She wrote in the margin: 'My telly prefers chocolate.' But it's all too easy, in a moment of carelessness, to mangle your grammar, and say something you never meant to say. So I watch out for this kind of slip and – rewrite it.

Enough for one posting. I don't imagine for a moment that I've said all there is to say on this subject, but something like this goes through my head when I'm rewriting. I'd welcome any additions and expansions – even corrections.

But I hope I've gone some way towards answering my student's question: 'When you rewrite, how do you know what words to change?'

In my next post, you lucky people, I'll consider the book or story as a whole. Unless someone else wants to do it?

.jpg?picon=1806)

By:

Susan Price,

on 2/6/2009

Blog:

An Awfully Big Blog Adventure

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

teaching,

Thomas Hardy,

Rewriting,

Susan Price,

Ghost Drum,

creative writing groups,

rewrites,

Jordan,

ghost-writer,

Tess of the D'Urburvilles,

Creative Writing Classes,

Add a tag

When I was a child, our house was littered with drawings, on used, opened-out envelopes, or old wallpaper, and even drawing-pads. My brother drew dinosaurs or battles (and battling dinosaurs), my sister drew swimming seals or people, and my father's drawings were usually of aeroplanes or birds.

They all had one thing in common: there would be repeated attempts at the drawings. My Dad, for instance, would do a sketch of the whole plane, and then, underneath, another drawing of its undercarriage, and another of its wings. He hadn't been happy with the first drawing, so he practiced the bits he felt needed improving. Turn the paper over, and there would be another, larger, better drawing of the whole plane.

These sketches taught me something without my ever realising I'd learned anything at all - 'You won't get things right the first time, so repeat them until you do'.

My own drawings were usually of people. As a child, I drew far more than I wrote; in my early teens, I drew and wrote about equally. After my first book was accepted, when I was sixteen, writing took over from drawing (and I haven't seriously drawn anything for about thirty years now). But the lesson that I never knew I'd learned moved with me from drawing to writing. If I wasn't happy with something I'd written, I rewrote it – and if I still wasn't happy, I rewrote it again, and again, many times if need be, until I thought I couldn't improve it any more.

I didn't think I was doing anything noteworthy. Rewriting was part and parcel of writing. It was just what you did; as much a part of writing as using a pen.

Years passed, and, in the way of impoverished writers, I started teaching Creative Writing. But between you and me, gentle reader, I was puzzled as to what 'Creative Writing' was exactly. And even more puzzled as to what I could teach my students. If I had ever stopped to think about what I did when I wrote a book, I couldn't remember doing it.

I consulted a few 'How to Write' books, to find out what those authors told their students, and it was enlightening. “Oh, I do that! Who'd have thought it?” I resolved only to steal those 'creative writing' tips that I could honestly say I used myself. (So you'll hear only a perfunctory mention in my classes about keeping notebooks, or meditating, or doing ten minutes of 'automatic writing' every morning.) My classes were about setting scenes, writing dialogue, building plots. It never occurred to me to tell anyone to rewrite, because to me rewriting was writing. I didn't think anyone would need to be told that.

Slowly, over weeks, it became apparent to me that the idea of rewriting had never, ever occurred to many – not just a few, but many – of my students. A lot of them seemed to think it was cheating. A real writer, they seemed to think – Thomas Hardy, let's say – just sat down and wrote Tess of the D'Urbervilles straight off, from beginning to end, never blotting a word; and then he packed it off to his publishers who printed it without asking for a single change. That's the kind of genius he was. That's the way a real writer works.

If my students wrote a story, and found themselves dissatisfied with it, they concluded that it was another failure, put it away, and tried to forget about it. The next thing they wrote, that might be perfect.

“Couldn't you,” I suggested nervously, not at all sure I was on firm ground here, “couldn't you rewrite it?”

They were astonished. But they'd finished it! And it wasn't any good. What was the point of wasting more time on it?

“But nothing I've ever written,” I said, “was much good in its first draft. But if I like the idea – if there are bits that are good – I rewrite it, and improve it. I've rewritten some things dozens of times over. I rewrote the whole of GHOST DRUM six or seven times, and I rewrote the ending many more times than that.”

Some of the class were quite excited by this revolutionary idea. Others were as plainly horrified, reminding me of a little girl in Year 4 of a school I once visited. Her story was so good, I told her, that she should rewrite it. The look she gave me would have reduced a lesser writer to a pair of smouldering boots.

But having belatedly realised that rewriting was actually a tool of the writer's trade that I'd never before suspected I was using, I became evangelistic about it. “Rewrite!” I cried to each new intake of students. “You must rewrite!”

And then one of my students stopped me in my tracks by asking, “But how do I know what parts I have to rewrite? How do I know which words I should change?”

Well – er – quite. Obviously, these are the technical complexities Jordan was referring to when she spoke of her ghost writer 'putting it into book words'. When a writer, like wot I am, takes the raw first draft and puts it into book words, what exactly is it I are doing?

I hadn't a clue. Look, I only write the stuff – I don't waste my time thinking about it, any more than a ditch-digger thinks much about ditch-digging. She just heaves another shovel-ful of mud.

But there were my students, waiting for an answer. So I gave thinking about it a try. And boy, did my brain hurt...

To be continued....

Some of you might be thinking… well isn’t that what any writer does? You animate your characters and make them speak! But this was an entirely different form of animation for me. It didn’t really involve words but sounds and it was the character/object that did all the work… not me… and it all happened in a few Digital Story-telling and Animation workshops at the Victoria & Albert Museum.

Armed with cameras we went to find prospective ‘clients/actors’ amongst the exhibitions. Many of my co-workshoppers were researchers with special interests and chose serious subjects like statues, tiles, pottery and fabric designs. But I suppose a little bit of laziness in me chose the first gallery up from the Sackler Design Centre where we were working – the 20th Century Gallery, where I found objects that already seemed to be people – a few chairs, an Alessi cork-screw, and down below in the Fashion Gallery some shoes. And they immediately began talking to each other in my head.

The joy of working on a Mac in iMovie is that you can take these very inanimate objects and imbue them with life. Make them not only speak but move! I was the ultimate puppeteer. What power! So armed with scissors, crayons, card, paper and glue (the comments on

Susan Price's Secret(ish) Love blog proved how beguiling all these objects can be!) I gave life to the Drum Armchair designed by Cecil Beaton in 1935.

With 18th century red-tasselled, silk boots kicking and arms taking up the drumstick motive on the back of the chair, he became the alter-ego of Punch forever imprisoned without legs, in his blue-striped, canvas stage on the beach. For a moment my newly animated chair with a fanfare of bugles and drums (no tiaras and ermine though – this wasn’t yesterday’s Queen’s Speech), and with animated arms creeping up his legs like caterpillars to the sound of marching feet, seemed more vital and vibrant and real than any character I’d written about in a book. (And if I wasn't too worried about crashing the bigblogadventure site, might have added the entire animation with much leg kicking, drumming and fanfare as well, to this blog.)

Hmmm? A new career? Should I take up animation instead of writing? A very amateurish film of 1 minute took I don’t know how many hours and hours of work and a total of 720 stop-frames to come alive. So now I’m trying to do the maths… how many hours and words does it take to make a character more or less alive in a book?

(Great to meet a fellow-blogger Lucy, at the Soc of Authors AGM with your new book,

Hoot-cat Hill. And

Nicky Browne, yes, agreed, I’m also losing the plot. Through this Animation Course I’ve now added another few layers to a desk that like yours, remains permanently something of an archaeological dig! I'm also spending an inordinate amount of time for someone who should be writing, playing animation not just with Punch's alter-ego but my own... pure escapism!)

At nineteen, using some of the vast profits from my second book, 'Twopence A Tub', I replaced my old cast-iron typewriter with a new, plastic one. It was baby-blue, I remember, and I could carry it in one hand. In truth it was a toy, intended for children, and I used to be asked how I could work on such a tiny thing. I never had problem with it (apart from the enraging task of changing ribbons, but that went with the territory in those days). It was an enormous relief not to have to practice weight-lifting every time I had to put it away.

At nineteen, using some of the vast profits from my second book, 'Twopence A Tub', I replaced my old cast-iron typewriter with a new, plastic one. It was baby-blue, I remember, and I could carry it in one hand. In truth it was a toy, intended for children, and I used to be asked how I could work on such a tiny thing. I never had problem with it (apart from the enraging task of changing ribbons, but that went with the territory in those days). It was an enormous relief not to have to practice weight-lifting every time I had to put it away.

I used the baby-blue for several years, but then decided to splash out on something for grown-ups. I bought a big, electric brute, but we never got on. Whenever I paused to think, it buzzed at me impatiently. I resented the buzzing. And I still had to change its ribbons.

It was about this time that a friend said to me, "Come upstairs and see my Amstrad..."

The Amstrad was an unlovely thing, but I was smitten as soon as saw how fast it printed off a page. At that time I wrote my books by hand, or pounded them out on a typewriter. The result was a heap of loose pages, full of crossings-out, rewrites, mistakes, notes to self. There would be mysterious signs - stars, arrows and loops - reminding me to hunt down the inserts written on yet other bits of paper. Before I could submit a book I had to turn this heap of jottings into a 'good copy'. It used to take me months.

I repeat, months. Just to copy out what I'd already written. Every single day, the first page I typed was so full of mistakes that it had to be redone. I would muddle the sequence of page-numbers and have to retype them. I had to estimate the word-number, which I hated almost as much as changing ribbons.

When I saw how you could skip about on the Amstrad's screen, changing words, shifting paragraphs, altering names, I was astounded. Find and replace! Spell-check! Word-count! A printer that didn't need a ribbon! I was ecstatic. And when I saw that it could print out a lengthy document in a morning, I had to have one.

But disillusionment always sets in. The first Amstrads never reminded you to save. Many a time I spent all day working on something, then switched off the machine and lost it all. I soon learned to save compulsively, every few words, a habit that's still with me.

The Amstrad printer could also be a trial. If you forgot to put the bale bar down (the bar that held the paper against the cylinder), the printer wouldn't work. It was easy to miss this small detail, and spend hours trouble-shooting, cajoling, phoning friends for help... Unlike modern computers, the Amstrad didn't tell you what was wrong, it didn't offer any hints or suggestions. The printer just sat there smugly, refusing to do the one thing it was made to do. It several times induced in me the kind of rage the early Plantagenet kings were famous for, when they rolled on the floor, foamed at the mouth and bit the rushes. If I'd had rushes, I would have bitten them.

You were also supposed to be able to leave the printer to do its thing, while you went and did something else, but in fact, you dared not leave it for a moment, because it used tractor-feed paper, and it always jammed. Even when you stood over it, watching, it frequently got out of sync and printed over the page perforations. Then there was nothing to do but stop the printer and start again.

Despite all this, I never, ever hankered to return to the typewriter, or pen and ink. I get quite irritated with writers who claim they could never sully their inspired creativity with vulgar technology, and that computers encourage sloppy writing. I think that's quite wrong. I think they encourage fierce editing rewriting and cutting, because they make it so easy. You don't have to retype and renumber pages because you decided to cut one out.

The solution to the Amstrad's drawbacks was to get a better computer, which I did, as soon as I could afford it. I'm writing this post on a laptop (much to my cat's indignation. He's sitting by me, glaring at the laptop, which is in his place. Occasionally he tries to climb on top of it). This light little laptop will check spelling, count words, print in different fonts and sizes, allow me to consult a thesaurus, and point out grammatical mistakes (though I never take any notice).

It connects to the internet, so if I need to check some fact, I log-on and Google. I can plug it into a printer which not only prints much faster than the Amstrad ever did, and never jams, but also faxes, scans and photo-copies. I don't even need to print very often, as I can submit my work by e-mail.

I can play music from the laptop's memory and load up my zen-stone for the gym. I can upload photographs from my digital camera and, minutes later, edit them on screen, and upload them to this blog. I can update my Tom-Tom, which guides me to schools on visits, and brings me home again.

I have more equipment and computer power on my lap than NASA used to put men on the moon. And I shall never have to change a typewriter ribbon again.

I remember my first, cast-iron typewriter with affection, but go back to it? You couldn't pay me enough.

.jpg?picon=1806)

By:

Susan Price,

on 8/7/2008

Blog:

An Awfully Big Blog Adventure

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

publisher,

Battle,

vikings,

Saxon,

Susan Price,

Saxons,

Feasting The Wolf,

1066,

Viking Age,

commissioned book,

Stamford Bridge,

Add a tag

I'm away with the Vikings again...

I'm away with the Vikings again...

My recent book, 'Feasting The Wolf' was set against the background of the Great Danish Army's invasion of England in the 9th Century. I'd hardly finished it before a publisher who shall be nameless (until the contract's signed) asked if I'd write for them 'a book for boys, set in the Dark Ages, full of adventure and violence.'

I need the money, so at once set about constructing a book. Colleagues have blogged recently about the joys of beginning a new book. By contrast, this is about the graft of working up a commissioned book to a brief.

'The Dark Ages' could mean anything from the 6th Century and King Arthur to the 8th and the Vikings, but it was always going to be Vikings, because I already know a lot about them.

I needed an idea, so I dredged up the plot of a book I'd written years ago and which had never been published. And I used my partner as a sounding board because he was once a boy, and so might have a better idea than me about what boys enjoy. How about, I suggested, a Viking trying to win enough gold to persuade the father of his sweetheart to let him marry her?

Yuck! Anything to do with weddings or kissing or girls was not on!

Okay, so how about our hero sees a beautiful sword for sale, but the swordsmith won't sell it, so he steals it, and -

"That makes him a thief!" said my partner, shocked.

Yes, and? Vikings were known, occasionally, to take without permission.

But no, no, no, I didn't understand. Heroes of boys' adventures cannot be thieves. They must be honourable and clean-living and right-thinking. This hero sounded less like a Viking every second. I wasn't getting anywhere.

In the end it was my brother (also once a boy) who said during one of our pub conversations, "Base it around the Battle of Stamford Bridge."

Well, that battle was right at the end of the Viking Age - literally, as the Viking Age can be defined as 'from early 8th Century to 1066'. Also, I usually avoid pinning any of my historicals to a definite date as arguing with historians can be so tiresome, I find. And Stamford Bridge, like the Battle of Hastings, has 'the one memorable date in English history'.

Still, I thought it was worth looking into, and started researching the battle. Before long I was fascinated and committed. Stamford Bridge it was going to be.

It was the battle fought in Yorkshire about twenty days before the Battle of Hastings, and for a story-teller, it has lots to offer. An invading Viking army numbering thousands. Impossible, heroic forced marches. Five thousand Vikings fighting to the death under the hot Yorkshire sun (really) without armour. Hardship, courage, heartache. Thank you, bro.

I invented and named my heroes, sketched out the story, and e-mailed it to my agent, so she could flog it. Instead, she flung it back. Too much history, she said, and not enough story. And expunge all mention of the Saxon hero wanting to be a monk! Christianity was the biggest turn-off! And there was I, thinking I was reflecting the way of that age, when Christianity was still fresh and vital.

But the main thing, with a commissioned book, is to sell it - so back to the laptop. History and Christianity out, story in. And my agent was, as usual, right. The story is coming to life as I get closer to the characters and ruthlessly cut the history. Can't wait to get to those five thousand hot, sweaty, doomed Vikings...

Read the rest of this post

Still, a writer like John Banville or Iris Murdoch demands attention (and rewards it). They write some sentences that I have to read three and four times to understand, but when I do, they become things of beauty. I know you're not advocating writing to the lowest common denominator, but I think that's the lesson many people take from writing instruction. Hemingway is dead!

John Banville and Iris Murdoch can be savoured by readers who have progressed to that level of appreciation. For children's writers to turn some words over once or twice, to listen to their cadence, to simplify, to shorten sentences, to opt for another word as Susan suggests, is to enrich the imagination and to recognise that our readers are very, very newly arrived at the art of reading on their own. I find myself still changing words and passages as I read to a class because of clunky, clumsy writing. Pity the book's already in print by then!

John Banville and Iris Murdoch can be savoured by readers who have progressed to that level of appreciation. For children's writers to turn some words over once or twice, to listen to their cadence, to simplify, to shorten sentences, to opt for another word as Susan suggests, is to enrich the imagination and to recognise that our readers are very, very newly arrived at the art of reading on their own. I find myself still changing words and passages as I read to a class because of clunky, clumsy writing. Pity the book's already in print by then!

oops! Sorry! This seems overly emphatic. My apologies must have pressed something twice.

Dianne, I make a definite distinction here between children's and YA novels. Think, for example, of the wonderful and not particularly accessible - yet eminently appropriate - diction of MT Anderson's Octavian Nothing. How sad it would be if he'd made all his sentences easy to read!

So glad you stressed the importance of reading aloud, Susan. You are absolutely right that language is there to be spoken aloud,and that this is the most powerful and direct way to communicate work to an audienece. Damn, but even sections of "Finnegans Wake" make sense when they're spoken.

Susan - your advice to 'read your work aloud' is, I think, incredibly valuable. Sometimes in the heat of writing (not just at first draft either) I can write long, convoluted sentences that need so much cut out of them it makes me cringe. Reading aloud clarifies things for me.

Dianne - when you said: 'I find myself still changing words and passages as I read to a class because of clunky, clumsy writing. Pity the book's already in print by then!' it made me snort with recognition. I thought it was just me!