new posts in all blogs

Viewing: Blog Posts Tagged with: trauma, Most Recent at Top [Help]

Results 1 - 7 of 7

How to use this Page

You are viewing the most recent posts tagged with the words: trauma in the JacketFlap blog reader. What is a tag? Think of a tag as a keyword or category label. Tags can both help you find posts on JacketFlap.com as well as provide an easy way for you to "remember" and classify posts for later recall. Try adding a tag yourself by clicking "Add a tag" below a post's header. Scroll down through the list of Recent Posts in the left column and click on a post title that sounds interesting. You can view all posts from a specific blog by clicking the Blog name in the right column, or you can click a 'More Posts from this Blog' link in any individual post.

By: Stacy A. Nyikos,

on 12/3/2014

Blog:

Stacy A. Nyikos

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

YA,

POV,

Vermont,

trauma,

Meg Wolitzer,

Richard Flanagan,

The Narrow Road to the Deep North,

Belzhar,

Man Booker Award,

Add a tag

Belzhar

Meg Wolitzer

YA

In the spirit of the cold winter months' clamor for a good book to curl up with, I present

Belzhar. I had the great pleasure of listening to Meg Wolitzer speak at BEA in May. She is an author of predominantly adult books who's tried her hand at YA and delivered a strong, new voice to enjoy.

Belzhar is the story of Jam who has basically given up on living after she loses her boyfriend. She stops functioning at school and becomes so depressed her parents and therapist send her to The Wooden Barn, a school for teens struggling with traumatic issues in Vermont. There, Jam is enrolled in a special English class that changes her life. Not only does she meet a new boy but also, at the same time, gets to communicate with the boy she's lost in a world unlike any other. Jam makes friends, rebuilds her life, but cannot move forward until she not only faces but relives the trauma that imploded her old life.

Woltizer's writing is strong, her characters both flawed and endearing, and her alternate reality within reality a great hook that entices the reader throughout the story.

There is an interesting trend, almost rule, within YA that the story is written in present tense. This is to make the reader feel closer to the events happening, and to mimic how very much teenagers are affected and live in the "now". It has made me wonder how exportable present tense storytelling is. I've used it in a picture book, just to try it out, to get a feel for the effect of tense. In a way, present tense makes even the past seem very present. It speeds up action and imbues what is happening with novelty, urgency and unpreditability. There's no telling how the story can end, especially if it is in first person POV. I just ran across a chapter of present tense in an adult novel,

The Narrow Road to the Deep North by Richard Flanagan (Man Booker Winner 2014). The story up until that moment had been told in simple past, then suddenly, present tense appears. It was a jarring, blast of air that pulled me out of the observer's position and into the narrative. I straightened and listened more closely. This had to be important. What a difference a tense can make.

For more great books to balance out the hustle and bustle of the end of the year, check out

Barrie Summy's site. Happy reading and a wonderful new year!

By: DanP,

on 7/27/2014

Blog:

OUPblog

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

surgery,

trauma,

anaesthesia,

broken bones,

*Featured,

oxford journals,

Science & Medicine,

Health & Medicine,

resuscitation,

x-ray,

anaesthetists,

radiology,

BJA,

british journal of anaesthesia,

Simon Howell,

trauma care,

trauma centres,

trauma medicine,

howell,

health,

Journals,

Medical Mondays,

hospitals,

NHS,

Add a tag

By Simon Howell

Major trauma impacts on the lives of young and old alike. Most of us know or are aware of somebody who has suffered serious injury. In the United Kingdom over five-thousand people die from trauma each year. It is the most common cause of death in people under forty. Many of the fifteen-thousand people who survive major trauma suffer life-changing injuries and some will never fully recover and require life-long care. Globally it is estimated that injuries are responsible for sixteen-thousand deaths per day together with a large burden of people left with permanent disability. These sombre statistics are driving a revolution in trauma care.

A key aspect of the changes in trauma management in the United Kingdom and around the world is the organisation of networks to provide trauma care. People who have been seriously hurt, for example in a road traffic accident, may have suffered a head injury, injuries to the heart and lungs, abdominal trauma, broken limbs, and serious loss of skin and muscle. The care of these injuries may require specialist surgery including neurosurgery, cardiothoracic surgery, general (abdominal and pelvic) surgery, orthopaedic surgery, and plastic surgery. These must be supported by high quality anaesthetic, intensive care, radiological services and laboratory services. Few hospitals are able to provide all of the services in one location. It therefore makes sense for the most seriously injured patients to be transported not to the nearest hospital but to the hospital best equipped to provide the care that they need. Many trauma services around the world now operate on this principle and from 2010 these arrangements have been established in England. Hospitals are designated to one of three tiers: major trauma centres, trauma units, and local emergency hospitals. The most seriously injured patients are triaged to bypass trauma units and local emergency hospitals and are transported directly to major trauma centres. While this is a new system and some major trauma centres in England have only “gone live” in the past two years, it has already had an impact on trauma outcomes, with monitoring by the Trauma Audit and Research Network (TARN) indicating a 19% improvement in survival after major trauma in England.

Not only have there been advances in the organisation of trauma services, but there have also been advances in the immediate clinical management of trauma. In many cases it is appropriate to undertake “early definitive surgery/early total care” – that is, definitive repair of long bone fractures within twenty-four hours of injury. However, patients who have suffered major trauma often have severe physiological and biochemical derangements by the time they arrive at hospital. The concepts of damage control surgery and damage control resuscitation have emerged for the management of these patients. In this approach resuscitation and surgery are directed towards stopping haemorrhage, performing essential life-saving surgery, and stabilising and correcting the patient’s physiological state. This may require periods of surgery followed by intervals for the administration of blood and clotting factors and time for physiological recovery before further surgery is undertaken. The decision as to whether to undertake early definitive care or to institute a damage control strategy can be complex and is made by senior clinicians working together to formulate an overview of the state of the patient.

Modern radiology and clinical imaging has helped to revolutionise modern trauma management. There is increasing evidence to suggest that early CT scanning may improve outcome in the most unstable patients by identifying life-threatening injuries and directing treatment. When a source of bleeding is identified it may be treated surgically, but in many cases interventional radiology with the placement of glue or metal coils into blood vessels to stop the bleeding offers an alternative and less invasive solution.

The evolution of the trauma team is at the core of modern trauma management. Advances in resuscitation, surgery, and imaging have undoubtedly moved trauma care forward. However, the care of the unstable, seriously injured patient is a major challenge. Transporting someone who is suffering serious bleeding to and from the CT scanner requires excellent teamwork; parallel working so that several tasks are carried out at the same time requires coordination and leadership; making the decision between damage control and definitive surgery requires effective joint decision-making. The emergence of modern trauma care has been matched by the development of the modern trauma team and of specialists dedicated to the care of seriously injured patients. It is to this, above all, that the increasing numbers of survivors from serious trauma owe their lives.

Dr Simon Howell is on the Board of the British Journal of Anaesthesia (BJA) and is the Editor of this year’s Postgraduate Educational Issue: Advances in Trauma Care. This issue contains a series of reviews that give an overview of the revolution in trauma care. The reviews expand on a number of presentations that were given at a two-day meeting on trauma care organised by the Royal College of Anaesthetists in the Spring of 2014. They visit aspects of the trauma patient’s journey from the moment of injury to care in the field, on to triage, and arrival in a trauma centre finally to resuscitation and surgical care.

Founded in 1923, one year after the first anaesthetic journal was published by the International Anaesthesia Research Society, the British Journal of Anaesthesia remains the oldest and largest independent journal of anaesthesia. It became the Journal of The College of Anaesthetists in 1990. The College was granted a Royal Charter in 1992. Since April 2013, the BJA has also been the official Journal of the College of Anaesthetists of Ireland and members of both colleges now have online and print access. Although there are links between BJA and both colleges, the Journal retains editorial independence.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via

email or

RSS.

Subscribe to only health and medicine articles on the OUPblog via

email or

RSS.

Image credit: Female doctor looking at x-ray photo, © s-dmit, via iStock Photo.

The post A revolution in trauma patient care appeared first on OUPblog.

By: Alice,

on 4/20/2014

Blog:

OUPblog

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

PTSD,

*Featured,

Stigma,

oxford journals,

Oral History Review,

Psychology & Neuroscience,

Carolyn Lunsford Mears,

Columbine High School shooting,

trauma recovery,

History,

Journals,

trauma,

columbine,

Oral History,

Add a tag

By Carolyn Lunsford Mears, Ph.D.

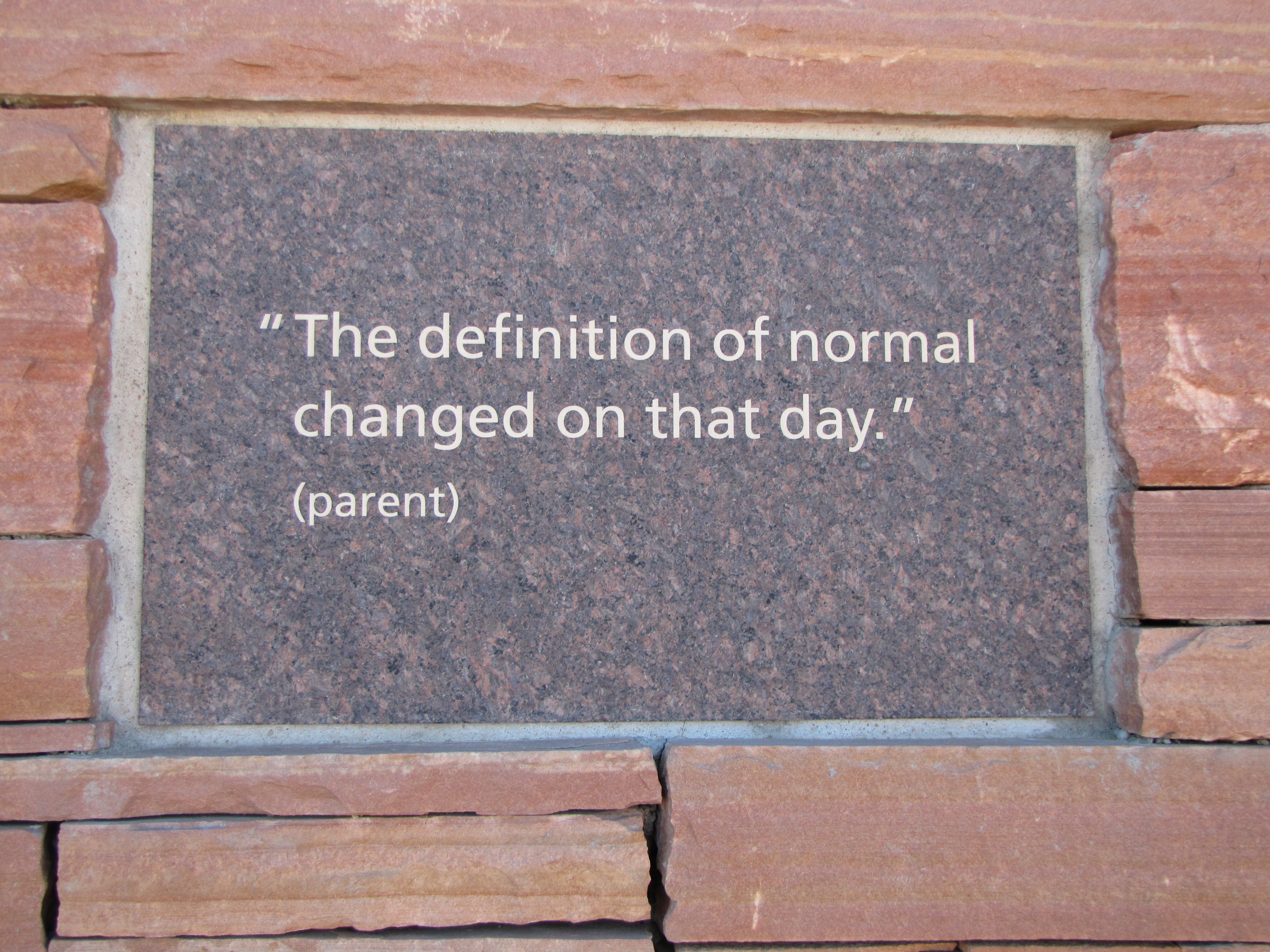

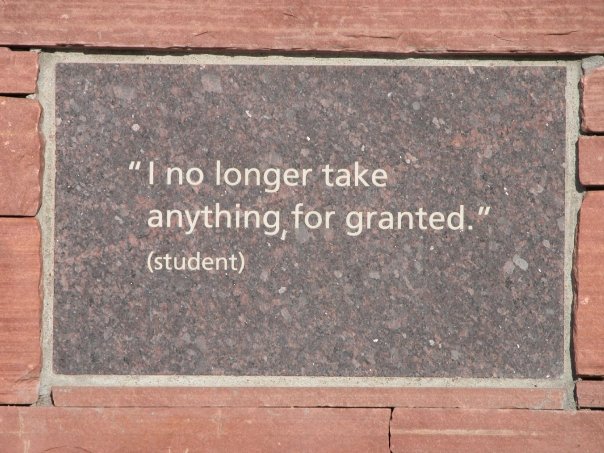

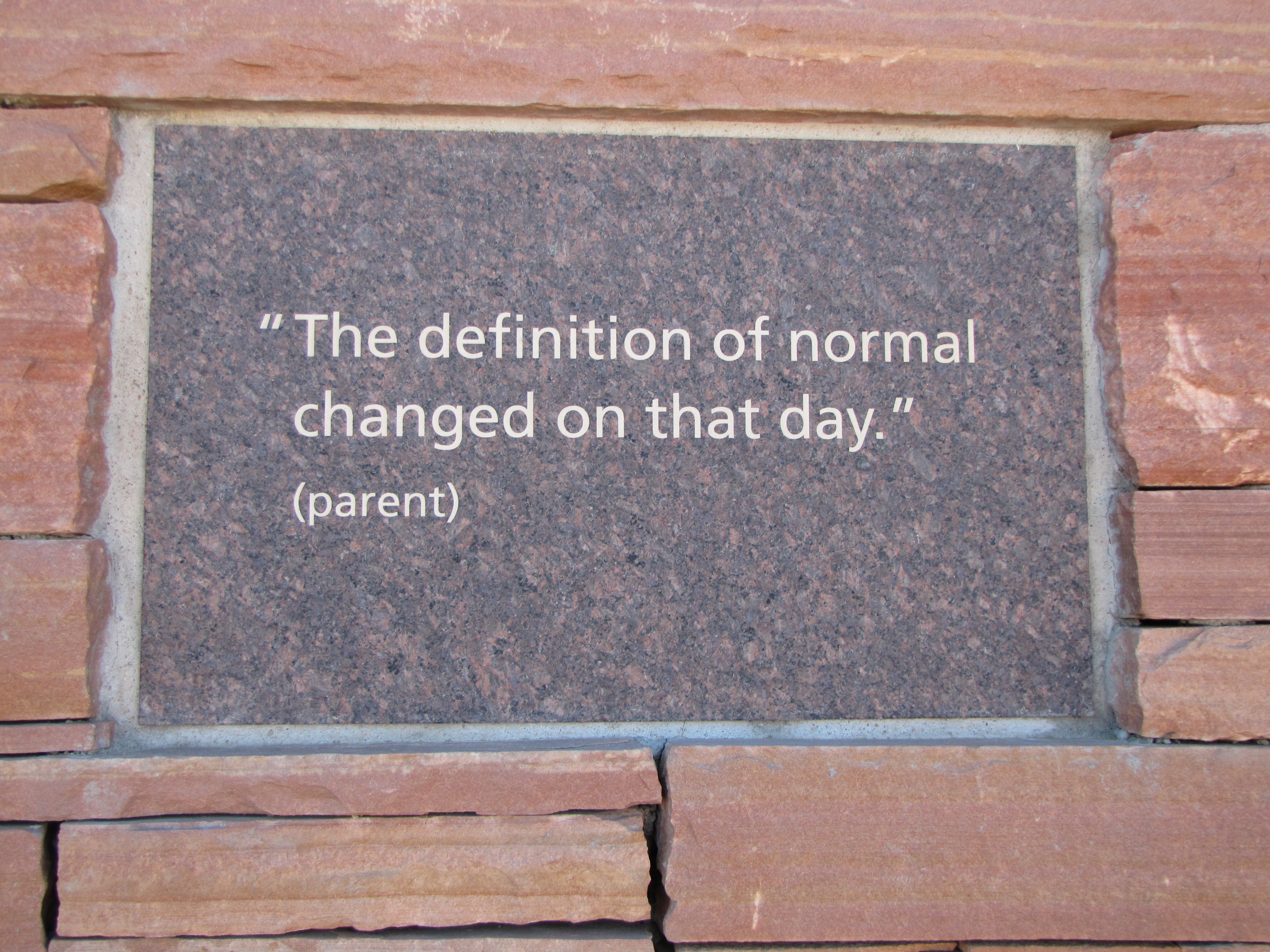

Fifteen years ago, 20 April 1999, it happened in my community… at my son’s school. Two heavily armed seniors launched a deadly attack on fellow students, teachers, and staff at Columbine High School in Jefferson County, Colorado.

As the event played out live on broadcast TV, millions around the globe watched in horror as emergency responders evacuated survivors and transported the wounded. At first, a quiet sort of disbelief mixed with shock and anguish descended upon us. Hours later, when the final tally was released – 15 dead, 26 injured – the reality of the tragedy brought the entire community to its knees.

The Columbine shootings became a benchmark event for school violence in the United States. I thought surely this was the turning point; nothing like this would ever happen again. Yet, barely a month later, Conyers, Georgia was added to the list of communities devastated by a shooting. At an alarming rate more towns and neighborhoods join the list, which now includes shootings in theaters, youth camps, shopping malls, and churches.

In 1999, trauma counseling primarily addressed PTSD (post-traumatic stress disorder) among veterans and victims of domestic violence, abuse, or sexual assault. Few strategies addressed wholesale community trauma. Even less was available to help parents manage the day-to-day challenges of parenting traumatized teens or to advise traumatized educators on teaching students who had witnessed murder in their own school. My response to the situation was to learn as much as I could about what helps people recover from the crushing shock and grief that follows catastrophe, which led me to doctoral research and a continuing focus on trauma as a human experience.

Mass shootings like at Columbine, Sandy Hook, and Utøya, Norway are only one type of trauma we may face. Life has risk, and even the best planning doesn’t ensure invulnerability. Random events happen… accidents, sudden death of a loved one, natural disaster, assault; the list seems endless. Thankfully, effective approaches for promoting recovery are becoming more widely known.

Whenever a tragic event grabs headlines and non-stop media coverage, generous offers support and resources start flooding in. For personal traumas, the situation is different; survivors often suffer in silence as they try to find a way to a livable future alone.

Research that offers insight into trauma’s effects can help us better understand the challenges people face. Efforts to promote public awareness of trauma and recovery offer a genuine benefit. Many are unaware that trauma is a natural human condition, a biologic response to an experience in which the victim feels powerless and overwhelmed in the face of life-threatening or life-changing circumstance.

The human brain is charged with survival, and traumatic response is its attempt to learn from a threatening situation in order to survive threat in the future. Humans try to make sense of their world, and when everything turns to chaos, the brain struggles to learn to identify future risks and to regain a feeling of competence and comfort in the everyday. Behaviors associated with traumatic stress include hypervigilence; extreme sensitivity to smells, sights, and sounds connected to the event; flashbacks; anxiety; anger; depression; and memory problems.

The good news is that even in the face of such challenge, people can successfully integrate their trauma-experience into their own personal history and reclaim their life with a renewed sense of purpose. Victims and their families find that this process takes time and sensitivity. For some, caring friends, family, clergy, and social resources are enough. Others, not everyone, may develop clinical PTSD that best responds to professional counseling. Unfortunately, some may try to “just forget about it” and “get back to the way things used to be,” thereby short-circuiting the process of real recovery. Unresolved trauma can take a high toll on relationships and quality of life.

Trauma’s effect on our lives, as individuals and as communities, may be more widespread than commonly realized. It isn’t a problem faced only by the military; it is not uncommon among civilians. Estimates are that in the United States about 6 out of every 10 men (60%) and 5 of every 10 women (50%) experience at least one traumatic event in their life. For men, it is likely an accident, physical assault, combat, disaster, or witnessing death or injury. For women, the risk is more likely domestic violence, sexual assault, or abuse. A 2004 study reported by the National Child Traumatic Stress Network found that over 50% of children had experienced a traumatic event.

A sense of shame and perceived stigma from needing psychological counseling may keep people from seeking help. Perhaps with education to increase understanding of trauma, more will realize that traumatic response is not a sign of weakness or defect. Instead, it can be a sign of a healthy, normal attempt to reclaim a sense of well-being and safety.

Life after tragedy can bring a deeper sense of purpose and heightened appreciation for living. A former Columbine student I had first interviewed for Reclaiming School in the Aftermath of Trauma: Advice Based on Experience and again later for another study said,

I used to think I was a totally different person after Columbine. That there is no way I could have emerged without being radically altered. And trust me, I was. But what I realize now is that at my core, at my very center, there continues the essence of who I was before, and maybe more importantly, who I was meant to be.

Outcomes such as this are possible. People are slowly recognizing trauma as a critical health issue, not only in the United States but worldwide. Public dialogue can reduce the stigma and isolation felt in trauma’s aftermath. Increased recognition of the occurrence of trauma among civilians and the military, combined with greater awareness of trauma as a natural response, can make a profound difference in the lives of millions. That’s a goal that deserves attention.

Carolyn Lunsford Mears, Ph.D., is a founder of Sandy Hook-Columbine Cooperative, a non-profit foundation dedicated to trauma recovery and resilient communities. She is an award-winning author, speaker, and researcher. She is the author of “A Columbine Study: Giving Voice, Hearing Meaning.” (available to read for free for a limited time) in the Oral History Review. Her 2012 anthology, Reclaiming School in the Aftermath of Trauma, won a prestigious Colorado Book of the Year Award, given by the Colorado affiliate of the National Endowment for the Humanities. She is a Fellow of the Royal Society of the Arts, alliance member of the National Centre for Therapeutic Care, Fellow of the Planned Environment Therapy Trust, and Board of Directors member for the I Love You Guys Foundation, and adjunct faculty at the University of Denver.

The Oral History Review, published by the Oral History Association, is the U.S. journal of record for the theory and practice of oral history. Its primary mission is to explore the nature and significance of oral history and advance understanding of the field among scholars, educators, practitioners, and the general public. Follow them on Twitter at @oralhistreview, like them on Facebook, add them to your circles on Google Plus, follow them on Tumblr, listen to them on Soundcloud, or follow the latest OUPblog posts via email or RSS to preview, learn, connect, discover, and study oral history.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only history articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Image credit: All images of the Columbine Memorial courtesy of Carolyn Lunsford Mears. Do not reproduce without permission.

The post Trauma happens, so what can we do about it? appeared first on OUPblog.

By: Alice,

on 12/22/2012

Blog:

OUPblog

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

Science & Medicine,

newtown,

Sandy Hook Elementary School,

newtown connecticut,

traumatized,

School-Based Professionals,

Supporting and Educating Traumatized Students,

Robert Hull,

teachers,

Psychology,

violence,

educators,

trauma,

hull,

traumatic,

*Featured,

Add a tag

By Robert Hull

As parents, children, and communities struggle to come to terms with the events in Newtown last week, it is important for educators and parents to be aware of just how deeply children can be affected by violence.

Community violence is very different from other sources of trauma that children witness or experience. Most trauma impacts individual students or small groups, whereas the violence that was experienced in Newtown affected the local community and the entire nation. The lack of warning and the unexpected nature of these kinds of events, combined with the seemingly random nature of the attack, contribute to a change in individuals’ personal views of the world, and their ideas about how safe they and their loved ones actually are. The world comes to seem more dangerous, people less trustworthy.

Exposure to trauma can impact several areas of children’s functioning. Teachers may notice that students who have experienced trauma appear to be shut down, bored, and/or hyperactive and impulsive. Interpersonal skills might be impacted, which can lead to social withdrawal, isolation, or overly aggressive behavior. Students might appear confused or easily frustrated. In addition they might have difficulty understanding and following directions, making decisions, and generating ideas or solving problems.

Family members and educators are often at a loss in how to support students following an event such as what happened in Newtown. The following are guidelines on helping students exposed to community violence:

- Teachers and family members should attempt to maintain the routines and high expectations of students. This directly communicates to children that they can succeed in the face of traumatic events.

- Reinforcing safety is essential following unpredictable violence. Remind children that the school is a safe place and that adults are available to provide assistance.

- Do not force children to talk. This can lead to withdrawal and downplaying the impact. A neutral conversation opening can be stated in this way: “You haven’t seemed yourself today. Would you like to share how you are feeling?”

- Teachers can model coping mechanisms such as deep breathing, relaxation and demonstrating empathy.

- Being flexible is a must following traumatic events. Teachers should allow students to turn in work late or to postpone testing.

- Educators should increase communication with parents in order to provide support that recognizes a specific child’s vulnerabilities.

There are several websites that can provide additional information on supporting students who have been exposed to violence. These include:

Robert Hull is an award-winning school psychologist with over 25 years of experience working in some of the most challenging of educational settings, and was for many years the facilitator of school psychology for the Maryland State Department of Education. Currently he teaches at the University of Missouri. He is the co-editor, with Eric Rossen, of Supporting and Educating Traumatized Students: A Guide for School-Based Professionals.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only psychology articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

The post Resources to help traumatized children appeared first on OUPblog.

By: Alice,

on 12/21/2012

Blog:

OUPblog

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

Education,

students,

schools,

Psychology,

trauma,

sensitive,

Social Sciences,

*Featured,

Science & Medicine,

Eric Rossen,

national tragedy,

newton connecticut,

sandy hook elementary,

School-Based Professionals,

Supporting and Educating Traumatized Students,

rossen,

Add a tag

By Eric Rossen

In the wake of another national tragedy, it is more apparent than ever that our schools must embrace a stronger role in supporting the mental health of our youth by developing trauma-sensitive schools. The mass shooting in Newtown, Connecticut that killed several staff and 20 elementary school students came less than two months after Hurricane Sandy, a storm that brought devastation and displacement to tens of thousands of people in the Northeast. Both events offer stark reminders of the acute stress our students may face when experiencing cataclysmic events. However, even in the absence of such tragedies, many of our nation’s children are in chronic distress.

Despite our collective efforts, youth continue to have adverse and traumatic experiences, such as chronic child maltreatment, domestic and community violence, homelessness, natural disasters, parental substance abuse, death of a loved one, and the list goes on. These experiences can significantly undermine the ability to learn, form relationships, and manage emotions and behavior; all critical components of succeeding in school and in life. To improve our country’s education system, we must first address these barriers to progress; and schools remain the most logical place to do it.

As a school psychologist, I have had the privilege of working with students, parents, and fellow educators to help students learn, develop, and grow in a healthy environment. I have also had the challenge of identifying the mental health problems that impede learning where all too often, the initial question is, “What’s wrong with you?” rather than “What happened to you?” or “How can we help?” Some believe that schools are in the business of educating, not mental health. On the contrary, supporting student mental health is a pre-requisite to learning, not an afterthought.

Interestingly, while only a fraction of kids who need mental health care actually receive it, 70-80% of those that do receive it get it at school. Schools often have a cadre of health and mental health supports available. For example, in the aftermath of Hurricane Sandy, the NYC Department of Education mobilized their staff with an all hands on deck approach. However, even with the most talented and ambitious group of mental health professionals in a school system, it’s unlikely that they can provide the full range of mental health supports to every student in need. A main challenge is first identifying students in need when a stressor is not as obvious as a hurricane or a school shooting. Moreover, some symptoms of childhood trauma may not fully manifest until adolescence, at a time where some may view that behavior as an unrelated outcome of that early experience.

Trauma-sensitive classrooms and schools provide an environment where all adults in the building have an awareness and sensitivity to the potential impact of trauma and adverse experiences on students’ lives. The initial thinking behind low academic performance or bad behavior is not automatically that the student is willfully disobedient, unmotivated, and unintelligent. Trauma-sensitive schools are places where all youth feel safe, connected, and supported — not just the youth who don’t need mental health care or those that need it most. Trauma-sensitive schools augment and supplement the herculean efforts of the school-based mental health professionals and in a sense, provide a continuous and universal mental health intervention system.

Creating trauma-sensitive schools requires a great deal of commitment. First, we know that most, if not all, teacher preparation programs don’t include training to prepare teachers to identify, teach, and support traumatized students. This is a problem, particularly given the demands on teacher preparation programs, and teachers themselves. The duties of a teacher are added on with regularity, and rarely removed. Therefore, we must infuse some content on the impacts of trauma and mental health on learning throughout teacher preparation and professional development programs.

Second, we must leverage the existing mental health professionals that exist in schools, including school psychologists, school counselors, school social workers, school nurses, and other school-based mental health providers. Utilizing them more effectively could include more regular consultation with teachers and administrators on developing trauma-sensitive strategies and perspectives. These individuals can also provide in-services to staff at no additional cost. Meeting this demand also means properly funding enough positions to provide these services along with the intensive direct services to students in need.

Finally, this requires a culture change — often more easily said than done. Luckily, some groups have emerged as leaders in creating trauma-sensitive schools, including the Massachusetts Department of Elementary and Secondary Education and the State of Washington Office of the Superintendant of Public Education. Much can be learned from the efforts of these pioneer systems.

Many of our kids are in distress, and our schools remain our frontline opportunity to support them.

Eric Rossen is the co-editor of Supporting and Educating Traumatized Students: A Guide for School-Based Professionals with Robert Hull. Eric Rossen, Ph.D., is a nationally certified school psychologist and licensed psychologist in Maryland. He currently serves as Director of Professional Development and Standards at the National Association of School Psychologists. Robert Hull, Ed.S., MHS, is a school psychologist in Prince George’s County Public Schools, Maryland, serves on the faculty at the University of Missouri, and holds a position as adjunct faculty at Goucher College.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only psychology articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

The post The case for creating trauma-sensitive schools appeared first on OUPblog.

By: Alice,

on 12/17/2012

Blog:

OUPblog

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

Clinical interviews,

How many more questions,

newtown connecticut,

Young Medically Ill Children,

Brenda Bursch,

explaining,

bursch,

traumatized,

children,

mental health,

parents,

Psychology,

calm,

understanding,

trauma,

shooting,

Techniques,

coping,

PTSD,

brenda,

distress,

*Featured,

Science & Medicine,

Health & Medicine,

Add a tag

By Brenda Bursch

Children look to their parents to help them understand the inexplicable. They look to their parents to assuage worries and fears. They depend on their parents to protect them. What can parents do to help their children cope with mass tragedy, such as occurred this week with the shooting at Sandy Hook Elementary School in Newtown, Connecticut?

The first thing that parents can do is to calm themselves. Remember that your children will react to your fear and distress. It will be reassuring to them to see that you are calm and not afraid to discuss the event with them.

Next, parents can consider limiting their children’s exposure to media coverage and to adult discussions of the shooting. Young children may have particular difficulty understanding what they see on news stories and what they overhear from adult discussions. They may also have difficulty assessing their own level of safety.

It can be helpful for parents to check in with their children in order to learn about their thoughts and emotional reactions to the shooting. After carefully listening to their children, parents can then determine if it is necessary to correct distressing misunderstandings, answer questions, validate feelings of anger or sadness, and remind their children about how their family members and others, including police officers, help to keep them safe.

Most children will not be traumatized by their media exposure to the shooting, but they may have questions or concerns. Some children will be fearful about returning to school or have other signs of distress, but will adjust with the support and reassurances provided by parents and others. Children who are especially sensitive, those who have a tendency to worry, those with little emotional support, and those who have been previously traumatized, may be more vulnerable.

Trauma symptoms among children vary, but include talking about the event, distress when reminded of the trauma, nightmares, new separation anxiety or clinginess, new fears, sleep disturbance, physical symptoms (such as stomachaches), and more irritability or tantrums. Children may regress, that is, soothe or express themselves in ways they did when they were younger. For example, they might want to sleep with parents or they may wet the bed. Parents might notice an increase in behavioral problems or a decrease in school functioning. If these symptoms don’t improve in the coming weeks, such children may benefit from professional assistance.

Children are reassured by calm and supportive adults, by their normal routines, and by age-appropriate information when they have questions or misconceptions. For those children with ongoing signs of trauma, effective treatments are available. For additional information, parents can access information from the National Child Traumatic Stress Network website.

Brenda Bursch, PhD is a pediatric psychologist and Professor of Psychiatry & Biobehavioral Science, and Pediatrics at the David Geffen School of Medicine at UCLA. She is co-author of “How Many More Questions?” : Techniques for Clinical Interviews of Young Medically Ill Children.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only psychology articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

The post How to help your children cope with unexpected tragedy appeared first on OUPblog.

...COLOR waiting to bud!

With spring still weeks away, and my yard still covered in its snowy white blanket, I just started imagining all of the lovely colors still sleeping. Soon the snow will be gone (but not before giving a hefty dose tonight!) and we will be graced with all of those beautiful hues from underground!

With spring still weeks away, and my yard still covered in its snowy white blanket, I just started imagining all of the lovely colors still sleeping. Soon the snow will be gone (but not before giving a hefty dose tonight!) and we will be graced with all of those beautiful hues from underground!

By the way, thanks for letting me join all of you here. Please feel free to visit me at my blog & website! I'd appreciate any feedback as I am still new to the world of freelancing! Thanks.