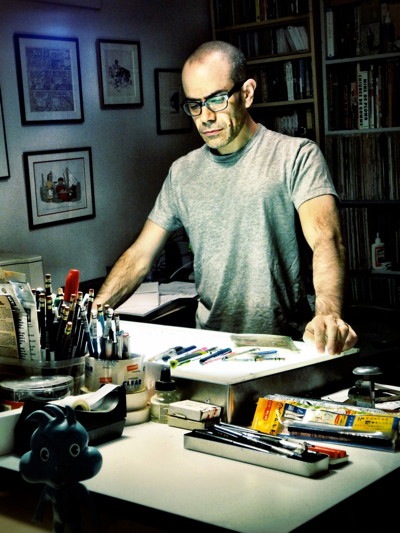

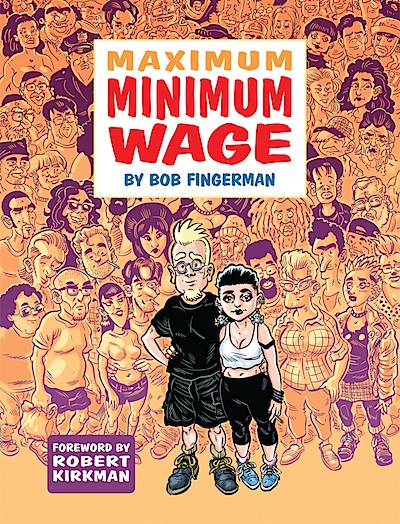

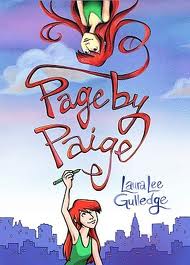

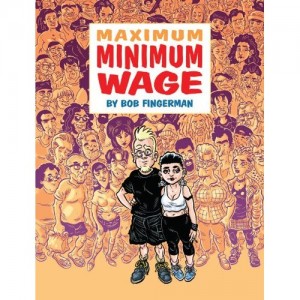

[Just out this week, Bob Fingerman's Maximum Minimum Wage is a grungy, uncomfrotably honest look at life in the playground known as New York City. It follows a young couple, Rob and Sylvia, as they try to survive crazy friends, cheapskate bosses and apartment hell—long before Friends and Girls, this is how it went down. Loosely based on elements of Fingerman's own life, the story has a long, somewhat complicated publishing history—it previously published by Fantagraphics in several formats—but all you need to know is that this is THE final version of the story thus far, as Fingerman originally intended it. The new book from Image includes a pin-up gallery—by artists from Mike Mignola to Gilbert Hernandez—and many extras and oversized pages for a handsome edition.

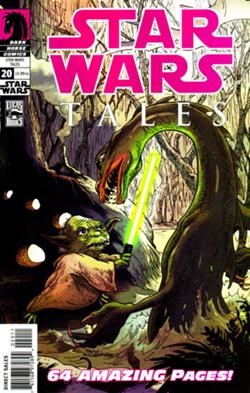

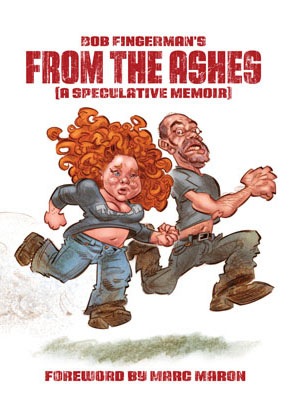

Fingerman has forged a busy, eclectic career, working on everything from an early stint on the Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles to Star Wars to Archie to the more recent post-apocalyptic saga From the Ashes. He's also branched out with two novels, Bottomfeeder and Pariah. I was eager to quiz Fingerman on some aspects of career building, as he's managed to survive in the business on a mix of creator owned and WFH work long before it become fashionable.

Disclaimer: as you may guess from the somewhat loose structure of the following interview, Fingerman and I have been friends for a long time. In fact if you squint real hard in Maximum Minimum Wage you might see an earlier version of me appearing in a few panels. It was great catching up with him and talking about the history of the book.]

The Beat: I was hoping to reread the whole book before this interview, but it is amazingly dense, Bob. This is a book you read night after night with a bookmark and set on your nightstand.

Fingerman: I’ve been accused of being dense many times.

The Beat: There have been a lot of different versions of Minimum Wage and you’ve tinkered with it quite a bit. You actually redrew the whole first chapter at one point, right?

Fingerman: Yes, for the previous incarnation of this thing, Beg the Question but it wasn’t so much redrawing the first chapter. I didn’t include it at all in Beg the Question—because the art style was just too different, so I kind of condensed it. So I took some stuff from Minimum Wage Book One” reworked it and redrew it and rewrote it and so forth and so on. But yes. I was actually toying with calling this the OCD edition because I can’t help myself. Michele [Fingerman’s wife] actually forbade me from going in and retouching it. And I said, “Oh, don’t worry, I’ll just do 10 panels.” And then I ended up probably reworking about 50 pages, redrawing some completely. I rewrote a bunch of the dialogue, too.

The Beat: So those who really want to get OCD about it themselves can sit down with the original issues and the previous collection, and see what tinkers you made.

Fingerman: Yes, if somebody besides me really wanted to make him or herself nuts, they would get out the original issues, they’d get out every edition of this and find all the changes.

The Beat: Well this is the internet, so someone will do it. I will say, it looks great. It’s a beautiful, beautiful volume.

Fingerman: When I look at Beg the Question now I get eye strain reading it because the type is like 2-point type. It’s nice to be able to actually read this thing and look at the art. I put all that work into the detail and then it was so plugged up. Now I think it looks the way it always should have looked.

The Beat: It looks fantastic. With all the tinkering that you have done over the years, let me ask you: do you think that’s primarily artistic in nature or is it maybe a psychological need to get the past correct? I mean, it is based on your life—not autobiographical, but it takes elements of your life, correct?

Fingerman: Yes. For some reason everyone has adopted the prefixed semi for autobiographical. I always prefer quasi-autobiographical as a word. I think quasi is more fun to say and I also think in some ways it seems more accurate. But in terms of tinkering, I don’t think it had anything to do with getting the past right. It’s more a matter of making it look the way I want to look. I hate to pull quotes from my own introduction but one point which I think I did need to make is when you’re a perfectionist there’s a difference between knowing you’ll never achieve perfection and not trying. I know I’ll never achieve perfection in anything I do but it’s not going to stop me from trying. So, I was dubbing what I have been doing with this Lucas-ing, only I hope my results are better.

The Beat: [Laughter] Lucas-ing. Yes.

Fingerman: Because I totally understand that compulsion.

The Beat: I guess it was probably nearly 15 years ago that you and I first talked about this book, and I think you told me that the theme was that love doesn’t last. Is that accurate?

Fingerman: It could be. I don’t know what I said 15 years ago. But to me, what always made this story interesting—because I don’t think of it as a romance comic by any means but maybe it’s an anti-romance comic—to me the theme is is that sometimes people are together that shouldn’t be together. And it doesn’t make either person a bad person. This is not a hero and villain situation. It’s just sometimes couples just shouldn’t be couples, and I think that’s what this is about. It’s about two people who actually do love each other but they’re not really their best mate.

The Beat: Do you think that Rob and Sylvia’s relationship is a failure?

Fingerman: You know, they give it a go. I don’t know if giving it a go is a failure.

The Beat: Looking at the book now I am totally struck by how it has life in the 90s captured in a perfect lens. But it just seems so distant. Life before the internet was like life before the car or the light bulb. I guess it’s like the light bulb because people would sit around with candles, then they just sat around watching TV or talking to each other instead of farting around on the internet. It’s crazy.

Fingerman: Ludicrous.

The Beat: I know! Do you have any thoughts on that? [Laughing]

Fingerman: Well, for years, but particularly lately, I’ve been thinking that I really do want to pitch this thing as a TV series, and part of that thought process is do you update it or do you make it a period piece? And to me, making it a period piece is quite stupid. That adds a lot of expense for no particularly good reason. But there are definitely things that would need updating in a very major way, and they’re all tech things because tech has changed our lives so radically. I don’t mean to sound like an old fuddy-duddy, although I just used the phrase fuddy-duddy, [Laughter] which I think accomplishes that. Anyway, oh you kids. But when you see young people now interacting they are generally not making eye contact. They’re looking at their devices. In the book, you’ve got people using things like pay phones, and nobody really has a computer. It’s addressed at the very beginning because it’s just starting to encroach just ever so slightly into their world that Rob doesn’t turn in like his column in an electronic format. He’s still actually writing these things, which you know maybe is even wrong for the time period it’s set in. Because it’s really set in the mid-nineties.

The Beat: Well, we had AOL then.

Fingerman: Yes, Rob’s just a bit of a Luddite, the character. But that would definitely change. But I mean there are certain things in there that I don’t even know how they’re done anymore. There’s a chapter of him running around trying to find work and the fact that he’s going from magazine to magazine is already dated because nobody uses illustration anymore. And he’s also running around with a portfolio and I don’t think anyone does that anymore.

The Beat: No, I don’t think they do. They all have Tumblr and Pinterest.

Fingerman: I don’t know how they get in touch with art directors.

The Beat: Well, I don’t think there are any art directors any more.You mentioned that you would love to do this as a TV series. You have done multimedia stuff, because it seems that’s what everybody in comics is doing these days. But you wrote two novels. Is it fair to call them horror novels?

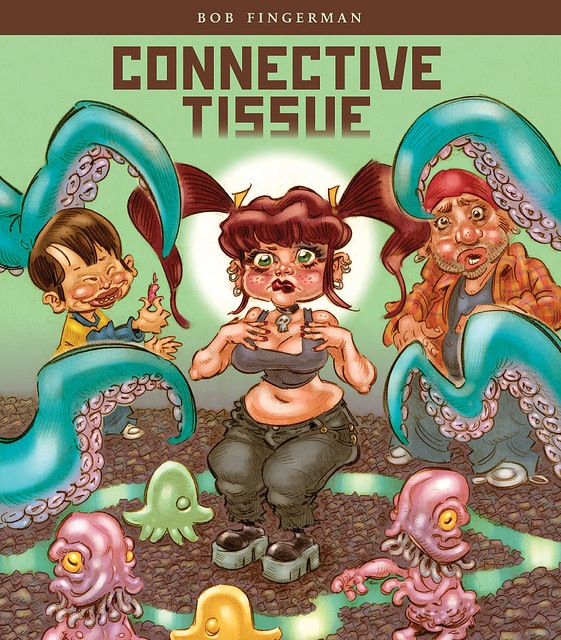

Fingerman: It’s fair. I don’t know if it’s accurate, but it’s fair. That’s not on you, that’s on the nature of how I do things. They’re both definitely genre books. When I started writing I started hearing terms I never heard before, like “dark fantasy” was a term I had never heard before. And I think that’s what some editor actually called Bottomfeeder. [Fingerman’s first novel, published by Dark Horse’s M Press imprint.]

The Beat: Bottomfeeder is about vampires, right? So now it might be “paranormal romance.” It might have actually shifted genres.

Fingerman: [Laughing] Except, there’s no romance in it. Both novels were me doing what I like to do, which is play with genre toys, but in my own way. I don’t think they were spine chillers. They’re certainly not that kind of thing. But I think they’re character based novels with horror trappings.

The Beat: Did you enjoy it? Was it a rewarding experience writing them?

Fingerman: Oh, I loved writing them and I’d love to write more. And I’ve got sequels for both of them. Actually, whenever I write anything I don’t think sequel. I’m just writing a self-contained thing. But like a lot of people, you get embroiled in your own thing and by the time you’re done and some months go by—or in the case of my things, a year—you think hey, wait a minute. That would be a good sequel. So I have things I would love to do. I actually did want Pariah to be a trilogy, but Tor had other plans.

The Beat: Well, you know, everybody’s doing it different ways now. You’re putting out Maximum Minimum Wage via Image, which is sort of self-publishing on many levels. What made you think that this was the route that you wanted to go? The Image route where you are controlling everything but you’re probably taking a little bit more of the risk. It’s not a money guarantee by any stretch of the imagination, especially with a beautiful but spendy book like Maximum Minimum Wage.

Fingerman: That’s true, yes. I have no idea how this will pan out in terms of seeing any money. I hope I will. But yes, it’s definitely not a guarantee. I just wanted it out. Doing this book became an idea that took hold. And Robert Kirkman, being in a position to make something like this happen with ease, it just kind of worked out that way. I sent Robert an email saying here’s what I want to do and within a few hours he wrote back and he said, “as a fan I want this, too. I will make it happen.” And it was just like that. But I think one of the main attractive points about doing it with Image, because I know Fantagraphics – well I don’t know, but I assume – if I had pitched the same thing to them, Fantagraphics would have said yes. But the wheels move a lot slower. And I really wanted to get something out. The last book of mine that came out was the mass market paperback of Pariah, my second novel. And that was in 2011. So 2012 was the first year of my career where nothing came out. And I thought that’s no good. It’s never for lack of trying. I’m always working on stuff. But again, the market’s different, and Minimum Wage, my tinkering aside, was ready to go, and Image moves at a much faster rate. I think it was like seven months from pitch to it being out.

The Beat: Yes. That’s kind of unheard of in the publishing world.

Fingerman: Exactly, exactly. And that’s one of the things I detest about mainstream publishing in particular, the glacial pace at which it moves, because it seems so pointless. For me, part of what I always would rationalize before, when I was more naïve, was, “Oh well, if they’re buying a book now and it’s coming out 18 months later, surely in that 18 months part of it’s going to be strategizing a marketing plan and promotions.” And then you see they do fuck all. [MacDonald laughs] So it’s like, why did you need 18 months to do nothing?

The Beat: Yes, I’ve learned that same thing in my own time in the book business actually.

Fingerman: Yes. So it’s ludicrous. They should just pound these things out unless they are really going to do a marketing blitz. I think that’s one of the reasons why publishing is the dinosaur it is, is because it moves like a fucking dinosaur.

The Beat: Interesting. Well, comic sales are up despite everything.

Fingerman: I’m not talking about comics. I’m talking about mainstream book publishing.

The Beat: But I think in comics, they’re just a lot more responsive to the marketplace for exactly the reason you just said.

Fingerman: Oh yes, exactly.

The Beat: I never actually heard anyone put it in those terms but I think that has something to do with it. I was looking forward to talking to you, because oflate there has been a lot of talking about DC artist Jerry Ordway and career options. You are probably from the first generation that came up in a world where you didn’t have to work for the Big Two. There were a lot of other options and you obviously took advantage of those, although you have worked for I know DC on occasion.

Fingerman: I’ve worked for all of them. I’ve worked for Marvel, DC, Archie you name it.

The Beat: Right. So you forged a fairly broad-based career. How do you see career planning now? There’s a lot of angst going around about “where will my retirement come from,” and “how do you forge a career after a certain point?” It seems right now there’s this vast influx of incredibly talented younger cartoonists who really aren’t even worrying about getting paid. They’re just getting their stuff out there. And then there’s kind of the Indy comics world where maybe they get to buy a sandwich once in a while off of their comics. And then there are people like you—I think you’ve gotten into comics with more of an expectation, even though you are in a dual-income household, that this was something you were doing for a living, this was something you were going to make money at.

Fingerman: Yes, boy, what a nice dream that was. Well, it’s interesting. I listen to that Marc Maron podcast, WTF. And I’m trying to think if it was his show. But some other comedian was quoting Chris Rock, and Chris Rock was talking about how if you can just build an audience of about 5,000 people, you’ll do all right. Maybe it was Louis C.K. And it had to do with that kind of niche thing. If you can just get 5,000 dedicated fans who will buy what you do, you can survive. I think that’s different than it was, and there’s also all these things like crowd sourcing. I’ve been thinking about Kickstarter for something. My first reaction to Kickstarter was kind of a knee-jerk negative one because I just thought oh, it’s public begging. But you see how legit it’s become, and you see how not just the project, but the people who are using Kickstarter—David Fincher is doing a Kickstarter. There are a lot of pretty big name people doing Kickstarters because I think everyone at this point in every creative field, publishing, moviemaking, music, whatever, is entirely sick of the status quo. In a way, it’s a very nerve-wracking time. But it’s also kind of an exciting time because there are opportunities now to pursue your folly outside the system, and basically inside a new system.

The Beat: We had a pre-interview lunch, and I said why don’t you put your comics on the web, and I think you said, “I hate web comics.”

Fingerman: I never read them.

The Beat: But with that in mind, even you can’t deny that the web is the main mechanism of promotion now for anything.

Fingerman: That’s true.

The Beat: So how do you see yourself moving forward in that way?

Fingerman: In little baby steps. Just the last couple of weeks, like actually today, my tech woes have to do with trying to update my website and update content and stuff like that. So I’m more than cognizant of the web and how it needs to be completely integrated into everything you do if you want to stay relevant. I think one of the problems for some of the other more dinosaur age people I know is they put up a website as a kind of capitulation to modern times, and then they never update it. You look at their website, I’m exaggerating here, but they might have animated GIFs of kittens hugging a heart and you think “What did you do? Get that in 1991?” And they’re like, “Oh yes, it’s great isn’t it?” If there’s an artist with an online portfolio and they haven’t updated in years, they might as well not have a website. I definitely am trying to direct traffic to my website. It’s more and more a priority. And there is content. I’ve been doing this sort of mutant-of-the-day thing since January, basically as an art exercise. But even there, in my head, because I always think to that next stage it’s like, well yes, I’ll do enough of these and then I can put out a book of them.

The Beat: While I was cleaning up recently, I actually found a little book of sketches that you had done back in the day. And then I sent it to the Library of Congress! You’ve talked about continuing Minimum Wage because the story is not finished.

Fingerman: Yes. I had my reasons for stopping doing it, but working on preparing this project put me back in that universe. It made me realize I want to start it up again.

The Beat: You would not at this point consider serializing it on the web?

Fingerman: I’d prefer not to.

The Beat: What is your reticence over it? Not that it’s the wrong decision, I’m just fascinated.

Fingerman: Nor is it a decision carved in stone. The idea of just spending—because you know my work, it’s labor intensive work—and the idea of just saying well, okay, I just spent six weeks or whatever drawing this chapter. Here, it’s free. As a person who lives in a world and has expenses, that bugs me. I’m fine with giving away samples for free. But the idea of giving the whole thing away for free rubs me the wrong way. It’s likely that if I started doing this as a regular serial book again, I figure 24-page chapters, if I gave away six or eight pages of each one online I’d think well that should be enough to whet someone’s appetite. But if they want the whole thing, why buy the cow when they’re giving away the milk for free? That’s kind of how I feel about the whole web comics and the web content thing. Why would I ever pay for it if I got it for free?

The Beat: You’ve talked about how Minimum Wage is set in a painfully real world and a lot of your other work is kind of, I guess people might paint you a little bit as a horror cartoonist, although I don’t think that’s entirely accurate. But you have done a lot of material in the zombie, apocalypse, vampire genres. Do you see yourself doing more of that in the future?

Fingerman: I hope so. I love genre stuff. For me, the most fun thing—and again that’s the way I like to play with that stuff—the most fun thing is to take these extraordinary creatures, genre creatures, or extraordinary settings, and then ground them. That’s how I like to play with it. I don’t think I could ever write big sweeping space operas or anything like that. I would have no interest in that. The one Star Wars comic I ever did was not only about the Jawas, but it was kind of a little satirical thing about a consumer advocate Jawa. But yes, basically any of the book pitches that I have in mind or out there now, they’re all genre stuff. You know me well enough to know that the post-apocalyptic setting is one I never seem to lose my taste for and I very much would like to do a big sprawling post-apocalyptic thing.

The Beat: Why do you think that is? Why do you love the post-apocalyptic world so much?

Fingerman: Well, for one thing chaotic stuff is fun to look at and fun to draw, and entropy to me is a particularly enjoyable thing. You show me a building that’s in disrepair covered in ivy and I’ll show you something that I think is beautiful. For me that’s the apocalypse, at least the apocalypse aesthetic. But also to me, it’s that lack of societal restraints. It’s this kind of forced freedom and forced reinvention. So that’s always going to be fun to think about.

The Beat: You did a book which I really loved which was From the Ashes in which you and your wife Michele were surviving in that post-apocalyptic world.

Fingerman: Yes, that was a book that has its highs and its lows. Obviously you have to have conflict. I didn’t make it a particularly happy realm, but there are definitely happy moments. Actually, thinking of everything I’ve ever done, that’s probably the most optimistic book I’ve ever done although it’s apocalyptic. That book has a truly happy ending, probably the happiest, sweetest ending of anything I’ve ever done.

The Beat: I just wrote something on The Beat the other day about The Walking Dead. Obviously you’re not alone in your love of post-apocalyptic fiction. But I am constantly amazed by how popular that show is. It’s the highest rated cable show of all times. Why do you think that is? I mean for the reason you just mentioned, but anything else about it?

Fingerman: That’s hard to say because the answer is obviously not a simple one because you can’t say it’s the best drama ever done for cable. I think Walking Dead is a great show. I love it. But I mean, why is it more popular than Justified? I don’t know. It clearly caught people’s fancy in a big way. Is it just because zombies are hot? That can’t be it. It’s a good soap opera, but that can’t be it because there are other good soap operas. I think people do love the grungy moments and there are plenty of those. Certainly there is a lot more evisceration and decapitation than probably any other show including Game of Thrones. So yes, it’s one of those lightning in a bottle things.

The Beat: One of the things I noted about it is that there’s no happy ending in sight. It isn’t even like Zombieland or 28 Days Later or From the Ashes where you turn the last page and you’re like okay, that ended. Walking Dead goes on and on and on. I think it’s that utter hopelessness of the situation, that there is no happy ending that you’re waiting for.

Fingerman: That is a very interesting thing. The zombie book that I wrote, Pariah, as I said I wanted it to be the first of a trilogy. So obviously I had in mind that it was going to continue and so forth. But to me it’s fascinating, because whenever you’ve written a zombie thing—and I have written several at this point—whenever you write those, inevitably somebody asks what would you do in the zombie apocalypse? And I always say, “I’d blow my fucking brains out.” Because what kind of life is that? That is the absolute least fun apocalypse you could imagine. I’m going to be a filthy, dirty person, hiding from people that want to eat me, oh, and that’s my life. That’s it. That’s all there is. Maybe I catch up on my reading. You’re Burgess Meredith in Time Enough At Last mixed with somebody who’s going to be eaten.

I don’t know. My father always said to me – and my dad’s seen a lot of rough times, he’s been around the world, World War II vet, blah, blah, blah – and he said the number one thing that we’re hard-wired for is survival. That survival instinct is even deeper than the one to procreate. And I guess all of these post-apocalyptic stories really are sort of putting money where their mouth is to that notion. That no matter how dire the situation, people are going to want to survive and some people maybe who are wired a little different than me would say oh, they are the ultimate evidence of how optimistic humans are. But I don’t know how much optimism there is on Walking Dead. It’s more just like let’s just stay alive to stay alive. Like the having the baby on that—you know me when it comes to babies, I think they’re a terrible idea under any circumstances. But in the apocalypse, it just seems ludicrous. It’s like, why the hell would you have a baby? What are you doing?

The Beat: Yes, in every episode of The Walking Dead, you’re not sure that a human race is going to continue. And I think that’s a pretty powerful theme. Well anyway, enough about wonderful Robert Kirkman’s work is. What’s he really like? [Laughing]

Fingerman: A wonderful smell of cinnamon about him.

The Beat: Maximum Minimum Wage is out now—any final thoughts on what you hope people get out of this tome?

Fingerman: I just hope they get a lot of entertainment out of it. I hope the people who already had it will enjoy this volume for its tweaks. It just looks so much nicer big. It makes a difference.

Great interview from one of comics great cartoonists.

I’ve been following Fingerman’s work for so long. I loved Zombieworld, White Like She and Skinheads in Love (search it out), but Minimum Wage was just another level. Growing up in NJ and NYC it just spoke to me on so many levels. Who hasn’t done the late night WhiteCastle runs?? haha. I have the collected Fantagraphics books and regular issues and still got this. That’s how great this book is. If you are on the fence and this interview still hasn’t sold you…do yourself a favor buy this book. Fingerman has a very unique voice and is a solid cartoonist.

Look forward to what comes next. If you ever need an artist look me up. haha.

peace,

Herc

Great interview!!! I love Bob’s work and I will be buying this new(version of the)book! He is one of the all time, best cartoonists ever. His writing and art and sense of character is awe-inspiring and I can’t wait to re-read this wonderful piece of work.

Minimum Wage has always been one of the unsung gems in comics – it’s wonderful to see it and Bob get the attention they deserve.

Will buying a third version of this make me happy to see (what I’m now told again is) the definitive edition, or will it bum me out for having to have bothered buying the previous two?

I totally understand Jacob, but this version is a large book. It’s an Oversized HC. I too own all the versions. I wish he didn’t change so many of the “love making” scenes though. haha. I still have the comics for that. If you have the Beg the Question HC it seems to be similar in content to that, but with the original GN that started it updated. The FC art section is awesome too.

peace,

Herc