By Marjorie Senechal

It was eerie, a gift from the grave. But I thank serendipity, not spooks. The gift, it turns out, was given forty years ago. When Dorothy Wrinch cleared out her office in the Smith College Science Center, she left her books for the library, her burgeoning notebooks and contentious correspondence for the archives, and three boxes of crystal models and model parts for me. But I was on sabbatical, and whoever stashed the boxes in the basement never told me. They’d be there still had a young colleague not gone rummaging for something else last fall and found them, “For Mrs. Senechal” pencilled on the top. And so they reached me at last. Forty years ago, I would have treasured these models as she had. But what can I do with them now?

Bring them to Montreal for show-and-tell? Crystallographers from all over the world are gathering there for their triennial Congress. The year 2014 is a special anniversary. On the eve World War I, an undergraduate at the University of Cambridge, William Lawrence Bragg, walking along the river behind his college, found the Rosetta Stone of the solid state. The then-recent discovery that crystals scatter x-rays had solved for the x: the mysterious rays are waves, like light. Bragg turned this around, deciphering the structures of simple crystals from the patterns in their scattered rays. Today’s textbooks trace the path from his work on table salt and diamond to the double helix, modern drug design, and the highest of high-tech materials. We forget that the path was neither easy nor straight. The boxes of chipped and scattered model parts Wrinch left me bear witness to the early years, when scientists argued over whether salt is really the 3-D atomic checkerboard Bragg said it was, whether proteins are chains or rings as Wrinch said they were, and how to interpret the diffraction patterns of mind-bogglingly complicated crystals.

But the boxes are bulky and too heavy for airlines that charge by the ounce. So what should I do with them? I’m deeply touched by the gift; I won’t throw them out. But if they were ever user-friendly, they aren’t anymore. It’s hard to fit the rods into the balls, and the paint on the balls is flaking. And who needs real models now, when we have vivid, interactive computer graphics on our iPads? (Let’s get that one out of the way: real models are still working tools for me and I’m not alone.) No, it’s not their aged parts, it’s their aged ideas that make these models obsolete.

Figure 1. A ball from the box of model parts that Dorothy Wrinch left for me.

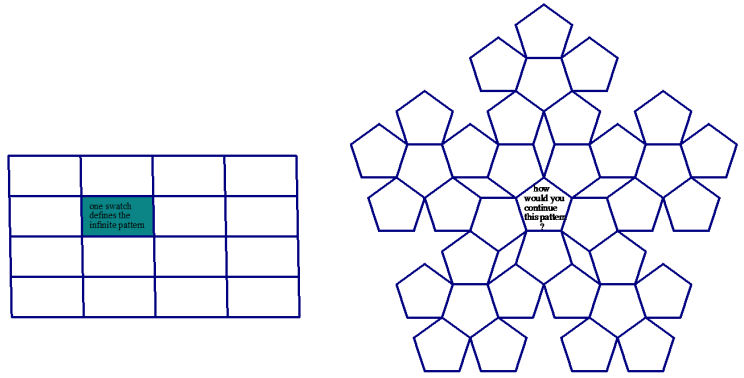

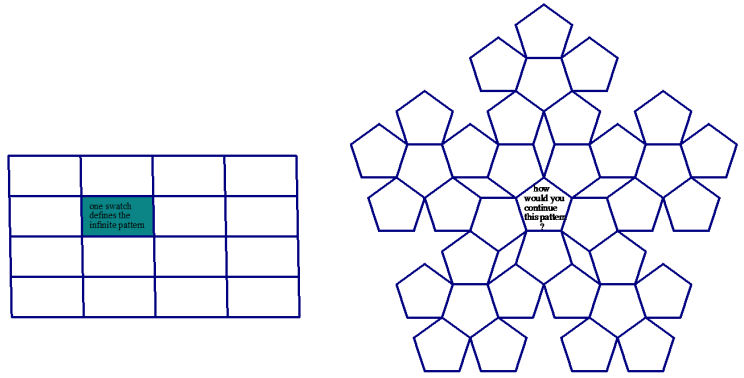

One book Wrinch didn’t leave for the library was a massive, gilded tome called Grammar of Ornament. It’s a cornerstone of the decorative arts, a veritable catalogue of rectangular swatches of floor, wall, and ceiling patterns created by people in all times and places. She loved this book because ornaments are like 2-D crystals. This analogy was crystallography’s chief paradigm, questioned by no one: the atoms in crystals repeat periodically in space. If you know one swatch (crystallographers call it a unit cell), you know the whole thing. A Grammar of Crystals would be a catalogue of swatches of 3-D atomic patterns. But that was then. Swatches are to modern crystallography as Pythagoras’s whole-number ratios are to √2 and pi. They’re still useful, but they’re not the whole story. The world of crystals, like the world of numbers, turns out to be bigger than anyone imagined.

Look closely at Wrinch’s wooden balls (Figure 1). The holes are drilled at the corners of squares, and at the centers of those squares, and at the centers of their edges. Six squares make a cube; if you picked up a ball and turned it around, you’d see the cubic pattern. With balls like these and rods to connect them, you can build 3-D swatches that stack like bricks to fill space. And that’s all you can build. But as the last century drew to a close, this paradigm crumbled. There are crystals, we now know, whose atomic patterns don’t repeat like ornaments. They spring surprises at every turn (Figure 2).

Figure 2. Left: To create this pattern, just fit the swatches together. Right: How would you extend this swatchless pattern?

Aperiodic crystals have opened a new chapter; what will its paradigms be? At this still-early stage, we conjecture, argue, explore the new terrain from every angle. It’s fitting, and telling, that the Montreal Congress will be a double celebration. If ever a scientific discovery changed the world, x-ray crystallography did. But, paradoxically, the Congress will give its plums and prizes this year to the scientists who consigned its paradigm to history’s basement and sent us back to basics.

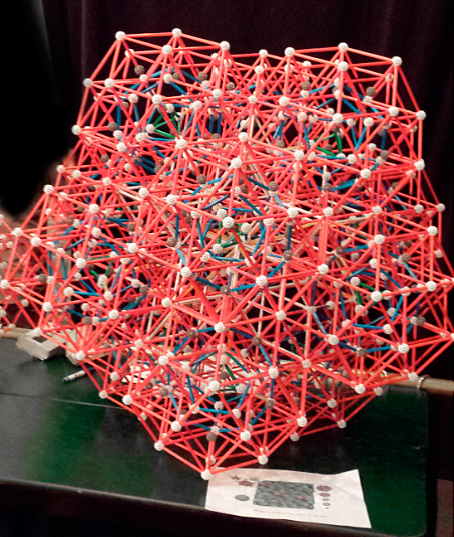

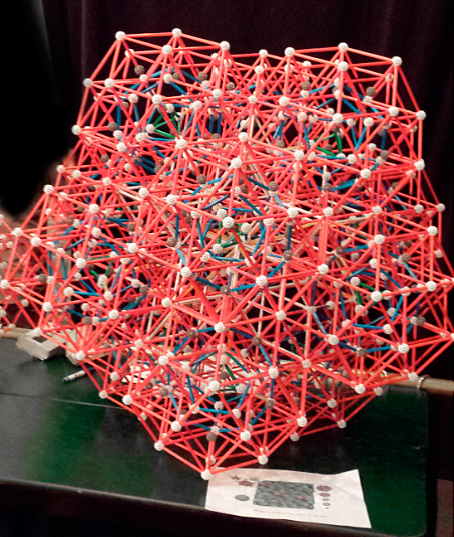

Figure 3. Compare the flexibility of this modern Zome Tool connector with its rigid ancestor in Figure 1.

Figure 4. A model of an actual non-repeating crystal structure made with Zome Tools by my students at the Park City Mathematics Institute, July 2014. Though aperiodic, this pattern of atoms can be extended in space.

I’ll put Wrinch’s models back in storage. She wouldn’t mind. “A science which hesitates to forget its founders is lost,” Alfred North Whitehead declared in 1916. A mature science, he explained, reconfigures itself as a logical structure from which the arguments and passions that built it are erased. Dorothy, then a student of his colleague Bertrand Russell, took the logical structure of science as a challenge. Later, when she ventured into less abstract realms, their reconfiguration was her mission. She would be delighted, I think, that so much of crystallography is automated today, and that the Grammar of Crystals is a databank. She would be delighted by new vistas to be reconfigured with modern models. And she would be delighted that crystallographers are still arguing.

Marjorie Senechal is the Louise Wolff Kahn Professor Emerita in Mathematics and History of Science and Technology, Smith College, and Co-Editor of The Mathematical Intelligencer. She is author of I Died for Beauty: Dorothy Wrinch and the Cultures of Science. She will be attending the International Union Of Crystallography Congress in Montreal 5-12 August 2014.

Chemistry Giveaway! In time for the 2014 American Chemical Society fall meeting and in honor of the publication of The Oxford Handbook of Food Fermentations, edited by Charles W. Bamforth and Robert E. Ward, Oxford University Press is running a paired giveaway with this new handbook and Charles Bamforth’s other must-read book, the third edition of Beer. The sweepstakes ends on Thursday, August 14th at 5:30 p.m. EST.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only physics and chemistry articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Image Credit: Photos by Marjorie Senechal.

The post Boxes and paradoxes appeared first on OUPblog.

By Marjorie Senechal

“March 8 is Women’s Day, a legal holiday,” I wrote to my mother from Moscow. “This is one of the many cute cards that is on sale now, all with flowers somewhere on them. We hope March 8 finds you well and happy, and enjoying an early spring! Alas, here it is -30° C again.”

I spent the 1978-79 academic year working in Moscow in the Soviet Academy of Science’s Institute of Crystallography. I’d been corresponding with a scientist there for several years and when I heard about the exchange program between our nations’ respective Academies, I applied for it. Friends were horrified. The Cold War was raging, and Afghanistan rumbled in the background. But scientists understand each other, just like generals do. I flew to Moscow, family in tow, early in October. The first snow had fallen the night before; women in wool headscarves were sweeping the airport runways with birch brooms.

None of us spoke Russian well when we arrived; this was immersion. We lived on the fourteenth floor of an Academy-owned apartment building with no laundry facilities and an unreliable elevator. It was a cold winter even by Russian standards, plunging to -40° on the C and F scales (they cross there). On weekdays, my daughters and I trudged through the snow to the broad Leninsky Prospect. The five-story brick Institute sat on the near side, and the girls went to Soviet public schools on the far side, behind a large department store. The underpass was a thriving illegal free-market where pensioners sold hard-to-find items like phone books, mushrooms, and used toys. Nearing the schools, we ran the ever-watchful Grandmother Gauntlet. In this country of working mothers, bundled bescarved grandmothers shopped, cooked, herded their charges, and bossed everyone in sight: Put on your hat! Button up your children!

At the Institute, I was supposed to be escorted to my office every day, but after a few months the guards waved me on. I couldn’t stray in any case: the doors along the corridors were always closed. Was I politically untouchable?

But the office was a friendly place. I shared it with three crystallographers: Valentina, Marina, and the professor I’d come to work with. We exchanged language lessons and took tea breaks together. Colleagues stopped by, some to talk shop, some for a haircut (Marina ran a business on the side). Scientists understand each other. My work took new directions.

I also tried to work with a professor from Moscow State University. He was admired in the west and I had listed him as a contact on my application. But this was one scientist I never understood. He arrived late for our appointments at the Institute without excuses or apologies. I was, I soon surmised, to write papers for him, not with him. I held my tongue, as I thought befits a guest, until the February afternoon he showed up two weeks late. Suddenly the spirit of the grandmothers possessed me. “How dare you!” I yelled in Russian. “Get out of here and don’t come back!” “Take some Valium” Valentina whispered; wherever had she found it? But she was as proud as she was worried. The next morning I was untouchable no more: doors opened wide and people greeted me cheerily, “Hi! How’s it going?”

International Women’s Day, with roots in suffrage, labor, and the Russian Revolution, became a national holiday in Russia in 1918, and is still one today. In 1979, the cute postcards and flowers looked more like Mother’s Day cards, but men still gave gifts to the women they worked with. On 7 March I was fêted, along with the Institute’s female scientists, lab technicians, librarians, office staff, and custodians. I still have the large copper medal, unprofessionally engraved in the Institute lab. “8 марта” — 8 March — it says on one side, the lab initials and the year on the other. The once-pink ribbon loops through a hole at the top. Maybe they gave medals to all of us, or maybe I earned it for throwing the professor out of the Institute.

Women’s Day medal, courtesy of Marjorie Senechal.

I’ve returned to Russia many times; I’ve witnessed the changes. Science is changing too; my host, the Academy of Sciences founded by Peter the Great in 1724, may not reach its 300th birthday. But my friends are coping somehow, and I still feel at home there. A few years ago I flew to Moscow in the dead of winter for Russia’s gala nanotechnology kickoff. A young woman met me at the now-ultra-modern airport. She wore smart boots, jeans, and a parka to die for. “Put your hat on!” she barked in English as she led me to the van. “Zip up your jacket!”

Marjorie Senechal is the Louise Wolff Kahn Professor Emerita in Mathematics and History of Science and Technology, Smith College, and Co-Editor of The Mathematical Intelligencer. She is author of I Died for Beauty: Dorothy Wrinch and the Cultures of Science.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only physics and chemistry articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

The post 8 марта 1979: Women’s Day in the Soviet Union appeared first on OUPblog.

Remembered today for her much publicized feud with Linus Pauling over the shape of proteins, known as “the cyclol controversy,” Dorothy Wrinch made essential contributions to the fields of Darwinism, probability and statistics, quantum mechanics, x-ray diffraction, and computer science. The first women to receive a doctor of science degree from Oxford University, her understanding of the science of crystals and the ever-changing notion of symmetry has been fundamental to science.

We sat down with Marjorie Senechal, author of I Died for Beauty: Dorothy Wrinch and the Cultures of Science, to explore the life of this brilliant and controversial figure.

Who was Dorothy Wrinch?

Dorothy Wrinch was a British mathematician and a student of Bertrand Russell. An exuberant, exasperating personality, she knew no boundaries, academic or otherwise. She sowed fertile seeds in many fields of science — philosophy, mathematics, seismology, probability, genetics, protein chemistry, crystallography.

What is she remembered for?

Unfortunately, she’s mainly remembered for her battle with the chemist Linus Pauling. Dorothy proposed the first-ever model for protein architecture, provoking a world-class controversy in scientific circles. Linus led her opponents; few noticed that his arguments were as wrong as her model was.

Why did he attack her research and career with such ferocity?

In those days before scientific imaging, scientists imagined. Outsized personalities, fierce ambitions, and cultural misunderstandings also played a role. And gender bias: Dorothy didn’t know her place. She didn’t suffer critics gratefully, or fools gladly. On a deeper level, the fight was philosophical. Imagination and experiment, beauty and truth are entangled inseparably, then and now.

Linus won two Nobel prizes. What became of Dorothy?

Dorothy, a single mother, came to the United States with her daughter at the beginning of World War II, and eventually settled in Massachusetts; she taught at Smith College for many years and wrote scientific books and papers. But her career never recovered. I wrote this book to find out why.

Marjorie Senechal is the Louise Wolff Kahn Professor Emerita in Mathematics and History of Science and Technology, Smith College, and Co-Editor of The Mathematical Intelligencer. She is the author of I Died for Beauty: Dorothy Wrinch and the Cultures of Science.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only science and medicine articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

The post Who was Dorothy Wrinch? appeared first on OUPblog.