Check out new artwork from the upcoming Cartoon Saloon film.

The post Cartoon Saloon’s ‘The Breadwinner’ Moves Into Production appeared first on Cartoon Brew.

Add a Comment

Check out new artwork from the upcoming Cartoon Saloon film.

The post Cartoon Saloon’s ‘The Breadwinner’ Moves Into Production appeared first on Cartoon Brew.

Add a Comment

July 1914 was the month that changed the world. On 28 June 1914, Archduke Franz Ferdinand was assassinated, and just five weeks later the Great Powers of Europe were at war. But how did it all happen? Historian Gordon Martel, author of The Month That Changed The World: July 1914, has been blogging regularly for us over the past few weeks, giving us a week-by-week and day-by-day account of the events that led up to the First World War.

Confusion was still widespread on the morning of 2 August 1914. On Saturday Germany and France had joined Austria-Hungary and Russia in announcing their general mobilization; by 7 p.m. Germany appeared to be at war with Russia. Still, the only shots fired in anger consisted of the bombs that the Austrians continued to shower on Belgrade. Sir Edward Grey continued to hope that the German and French armies might agree on a standstill behind their frontiers while Russia and Austria proceeded to negotiate a settlement over Serbia. No one was certain what the British would do – especially not the British.

Shortly after dawn Sunday German troops crossed the frontier into the Grand Duchy of Luxembourg. Trains loaded with soldiers crossed the bridge at Wasserbillig and headed to the city of Luxembourg, the capital of the Grand-Duchy. By 8.30 a.m. German troops occupied the railway station in the city centre. Marie-Adélaïde, the grand duchess, protested directly to the kaiser, demanding an explanation and asking him to respect the country’s rights. The chancellor replied that Germany’s military measures should not be regarded as hostile, but only as steps to protect the railways under German management against an attack by the French; he promised full compensation for any damages suffered.

The neutrality of Luxembourg had been guaranteed by the Powers in the Treaty of London of 1867. The prime minister immediately protested the violation at Berlin, Paris, London, and Brussels. When Paul Cambon received the news in London at 7.42 a.m. he requested a meeting with Sir Edward Grey. The French ambassador brought with him a copy of the 1867 treaty – but Grey took the position that the treaty was a ‘collective instrument’, meaning that if Germany chose to violate it, Britain was released from any obligation to uphold it. Disgusted, Cambon declared that the word ‘honour’ might have ‘to be struck out of the British vocabulary’.

The cabinet was scheduled to meet at 10 Downing Street at 11 a.m. Before it convened Lloyd George held a small meeting of his own at the chancellor’s residence next door with five other members of cabinet. They were untroubled by the German invasion of Luxembourg and agreed that, as a group, they would oppose Britain’s entry into the war in Europe. They might reconsider under certain circumstances, however, ‘such as the invasion wholesale of Belgium’.

When they met the cabinet found it almost impossible to decide under what conditions Britain should intervene. Opinions ranged from opposition to intervention under any circumstances to immediate mobilization of the army in anticipation of despatching the British Expeditionary Force to France. Grey revealed his frustration with Germany and Austria-Hungary: they had chosen to play with the most vital interests of civilization and had declined the numerous attempts he had made to find a way out of the crisis. While appearing to negotiate they had continued their march ‘steadily to war’. But the views of the foreign secretary proved unacceptable to the majority of the cabinet. Asquith believed they were on the brink of a split.

After almost three hours of heated debate the cabinet finally agreed to authorize Grey to give the French a qualified assurance. The British government would not permit the Germans to make the English Channel the base for hostile operations against the French.

While the cabinet was meeting in the afternoon a great anti-war demonstration was beginning only a few hundred yards away in Trafalgar Square. Trade unions organized a series of processions, with thousands of workers marching to meet at Nelson’s column from St George’s circus, the East India Docks, Kentish Town, and Westminster Cathedral. Speeches began around 4 p.m. – by which time 10-15,000 had gathered to hear Keir Hardie and other labour leaders, socialists and peace activists. With rain pouring down, at 5 p.m. a resolution in favour of international peace and for solidarity among the workers of the world ‘to use their industrial and political power in order that the nations shall not be involved in the war’ was put to the crowd and deemed to have carried.

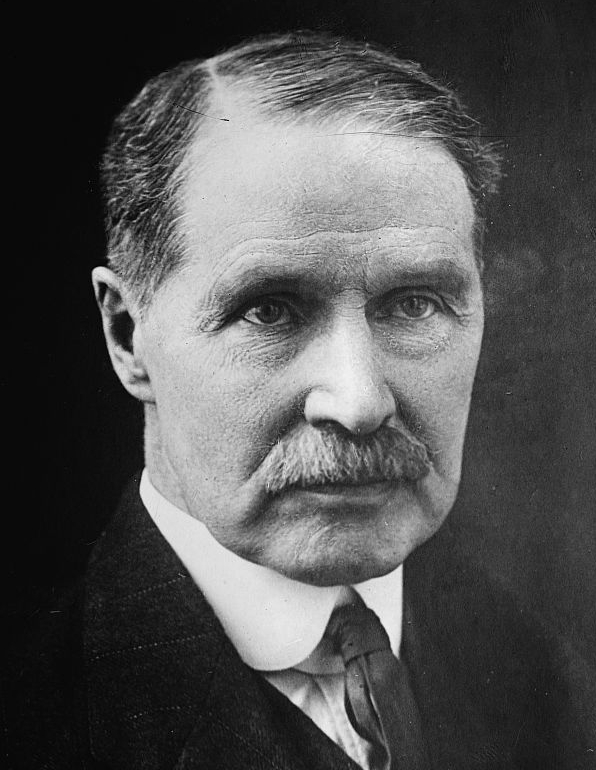

Andrew Bonar Law, British leader of the opposition. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons

The anti-war sentiment, which was still strong among labour groups and socialist organizations in Britain, was rapidly dissipating in France. On Sunday morning the Socialist party announced its intention to defend France in the event of war. The newspaper of the syndicalist CGT declared ‘That the name of the old emperor Franz Joseph be cursed’; it denounced the kaiser ‘and the pangermanists’ as responsible for the war. In Germany three large trade unions did a deal with the government: in exchange for promising not to go on strike, the government promised not to ban them. In Russia, organized opposition to war practically disappeared.

Shortly before dinner that evening the British cabinet met once again to decide whether they were prepared to enter the war. The prime minister had received a promise from the leader of the Unionist opposition, Andrew Bonar Law, that his party would support Britain’s entry into the war. Now, if the anti-war sentiment in cabinet led to the resignation of Sir Edward Grey – and most likely of Asquith, Churchill and several others along with him – there loomed the likelihood of a coalition government being formed that would lead Britain into war anyway.

While the British cabinet were meeting in London they were unaware that the German minister at Brussels was presenting an ultimatum to the Belgian government at 7.00 p.m. The note contained in the envelope claimed that the German government had received reliable information that French forces were preparing to march through Belgian territory in order to attack Germany. Germany feared that Belgium would be unable to resist a French invasion. For the sake of Germany’s self-defence it was essential that it anticipate such an attack, which might necessitate German forces entering Belgian territory. Belgium was given until 7 a.m. the next morning – twelve hours – to respond.

Within the hour the prime minister took the German note to the king. They agreed that Belgium could not agree to the demands. The king called his council of ministers to the palace at 9 p.m. where they discussed the situation until midnight. The council agreed unanimously with the position taken by the king and the prime minister. They recessed for an hour, resuming their meeting at 1 a.m. to draft a reply.

Gordon Martel is a leading authority on war, empire, and diplomacy in the modern age. His numerous publications include studies of the origins of the first and second world wars, modern imperialism, and the nature of diplomacy. A founding editor of The International History Review, he has taught at a number of Canadian universities, and has been a visiting professor or fellow in England, Ireland and Australia. Editor-in-chief of the five-volume Encyclopedia of War, he is also joint editor of the longstanding Seminar Studies in History series. His new book is The Month That Changed The World: July 1914.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only history articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

The post The month that changed the world: Sunday, 2 August 1914 appeared first on OUPblog.

As a regional businessman and a fledgling band manager, Brian Epstein presumed that the Beatles’ record company (EMI’s Parlophone) and Lennon and McCartney’s publisher (Ardmore and Beechwood) would support the record. This presumption would prove false, however, and Epstein would need to draw on all of the resources he could spare if he were to make the disc a success. He began with what he knew from the retail end of the industry and commenced rallying Liverpudlians to write letters to both Radio Luxembourg and the BBC asking them to play “Love Me Do.”

Just as the stations XERF (in Ciudad Acuña, Mexico) and CKLW (in Windsor, Ontario, Canada) were able to broadcast deep into the United States with transmitters many times more powerful than FCC-regulated American stations, a station in the Grand Duchy of Luxembourg carpeted most of Western Europe. Perhaps surprisingly, Radio Luxembourg (broadcast in the Medium Wave band) was British-owned and its English-language service became a primary outlet for UK businesses whose advertising the BBC declined. (The BBC refused to broadcast anything that suggested product promotion.) Radio Luxembourg suffered its sometimes-scratchy signal; but British listeners tuned in every night to embrace the pop music that Aunty Beeb would not play.

British corporations like EMI and London music publishers like Essex Music directly controlled much of the station’s airtime by buying broadcast blocks during which they played pre-recorded programs. Indeed, on Monday 8 October 1962, the Beatles taped an interview at EMI’s headquarters in London, which Radio Luxembourg broadcast along with their recording of “Love Me Do” on Friday 12 October. (George Harrison later recalled the thrill of first hearing himself on that radio broadcast.) The Liverpool letters solicited by Epstein that arrived in Luxembourg eventually arrived at EMI in London where the manager hoped they would catch corporate attention and result in better domestic support for the Beatles and their releases.

Tony Barrow, whom Epstein had originally contacted at Decca Records in his quest to get the Beatles a recording contract, began work for NEMS (North End Music Stores) as the Beatles’ publicist. (He could hardly have imagined how his job description would evolve from soliciting the press’s attention to holding them at arm’s length.) As a reviewer and a liner-note writer, Barrow had often worked from press materials prepared by agents and managers. These releases could vary significantly in kind and quality, but among them, Barrow thought that the press kits from Leslie Perrin’s office (which had represented London’s infamous Raymond’s Revue Bar, among others) were particularly effective. Notably, a color-coded press kit walked readers through a client’s story, which made a reviewer’s tasks easier. Barrow appropriated this format in his preparations for promoting the Beatles.

The role of the press agent involved finding the right people to contact and, for that, Barrow needed names, addresses, and phone numbers. Coincidentally, he knew someone who had recently left Decca’s press office. The Beatles’ new agent presumed that the individual would have taken a copy of the company’s mailing list and, after a casual meal, they reached a mutually beneficial agreement. Brian Epstein’s new part-time press manager walked away with a cache of contacts.

Barrow began by introducing the Beatles to London’s music press, escorting the Liverpudlians from the Denmark Street offices of New Musical Express to Fleet Street’s Melody Maker. They were willing to go almost anywhere to meet anyone with access to print or broadcast media. For example, on 9 October 1962 (the day after taping the Radio Luxembourg program), they visited the offices of Record Mirror so that writers there could see how different they were from other entertainers and to hopefully experience some of the charm that had swayed George Martin.

The mixed results both encouraged the band and its manager, and disappointed them. Alan Smith, writing in the New Musical Express (26 October 1962), briefly introduced the band, highlighting how Lennon and McCartney had written their “hit.” However, if you were the Beatles searching the papers for even the briefest mention (which they did weekly), you found little.

Brian Epstein in a 1967 interview would justifiably take credit for some of the band’s early success, citing his diligence and perseverance. The slow climb of “Love Me Do” up the charts would be his vindication. By December 1962, despite setbacks, the single increased sales and nudged into the top twenty on the most respected (if selectively read) chart. They were poised for something and they were sure ‘twas for success.

Gordon Thompson is Professor of Music at Skidmore College. His book, Please Please Me: Sixties British Pop, Inside Out, offers an insider’s view of the British pop-music recording industry. Check out Gordon Thompson’s posts on The Beatles and other music here.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only music articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

The post Selling the Beatles, 1962 appeared first on OUPblog.

A funny thing has happened: as hand-drawn studio-produced animated features have all but disappeared from the American animation scene, European and Asian studios are enjoying a mini-renaissance of drawn feature films. The latest example is Ernest et Célestine, adapted from a French children’s book series about the unlikely friendship between a gruff bear with artistic ambitions and an intelligent mouse who doesn’t want to become a dentist. The clip above gives a taste of the film’s breezy visual style that mixes broken-line characters with watercolor-style backgrounds.

Directors are Benjamin Renner, Stéphane Aubier, Vincent Patar, the latter two of whom directed the recent stop-motion feature A Town Called Panic. The 80-minute feature is a co-production between France (Les Armateurs, Maybe Movies, Studiocanal France), Belgium (La Parti) and Luxembourg (Mélusine Productions). Ernest et Célestine will have its world premiere this week at the Directors’ Fortnight, which takes place alongside the Cannes Film Festival.

Another extended film clip as well as a video showing the paperless production pipeline can be viewed after the jump. It’s all in French, but don’t let that stop you from taking a peek.

Cartoon Brew |

Permalink |

No comment |

Post tags: Belgium, Benjamin Renner, Ernest et Célestine, France, Luxembourg, Stéphane Aubier, Vincent Patar