new posts in all blogs

Viewing: Blog Posts Tagged with: UNH, Most Recent at Top [Help]

Results 1 - 4 of 4

How to use this Page

You are viewing the most recent posts tagged with the words: UNH in the JacketFlap blog reader. What is a tag? Think of a tag as a keyword or category label. Tags can both help you find posts on JacketFlap.com as well as provide an easy way for you to "remember" and classify posts for later recall. Try adding a tag yourself by clicking "Add a tag" below a post's header. Scroll down through the list of Recent Posts in the left column and click on a post title that sounds interesting. You can view all posts from a specific blog by clicking the Blog name in the right column, or you can click a 'More Posts from this Blog' link in any individual post.

.jpg?picon=160)

By: Matthew Cheney,

on 9/13/2015

Blog:

The Mumpsimus

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

William Plomer,

UNH,

Vera Brittain,

Elizabeth Bowen,

John Lehmann,

Winifred Holtby,

Writers,

PhD,

Christopher Isherwood,

Woolf,

Add a tag

The new school year has started, which means I've officially ended the work I did for a summer research fellowship from the

University of New Hampshire Graduate School, although there are still a few loose ends I hope to finish in the coming days and weeks. I've alluded to that work previously, but since it's mostly finished, I thought it might be useful to chronicle some of it here, in case it is of interest to anyone else. (Parts of this are based on my official report, which is why it's a little formal.)

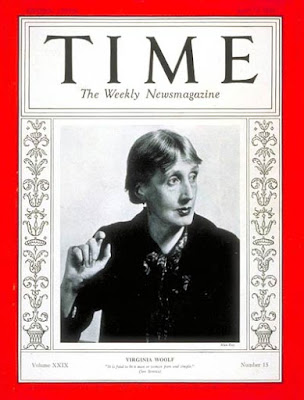

I spent the summer studying the literary context of Virginia Woolf’s writings in the 1930s. The major result of this was that I developed

a spreadsheet to chronicle her reading from 1930-1938 (the period during which she conceived and wrote her novel

The Years and her book-length essay

Three Guineas), a tool which from the beginning I intended to share with other scholars and readers, and

so created with Google Sheets so that it can easily be viewed, updated, downloaded, etc. It's not quite done: I haven't finished adding information from Woolf's letters from 1936-1938, and there's one big chunk of reading notebook information (mostly background material for

Three Guineas) that still needs to be added, but there's a plenty there.

Originally, I expected (and hoped) that I would spend a lot of time working with periodical sources, but within a few weeks this proved both impractical and unnecessary to my overall goals. The major literary review in England during this period was the

Times Literary Supplement (TLS), but working with the TLS historical database proved difficult because there is no way to access whole issues easily, since every article is a separate PDF. If you know what you’re looking for, or can search by title or author, you can find what you need; but if you want to browse through issues, the database is cumbersome and unwieldy. Further, I had not realized the scale of material — the TLS was published weekly, and most reviews were 800-1,000 words, so they were able to publish about 2,000 reviews each year. Just collecting the titles, authors, and reviewers of every review would create a document the length of a hefty novel. The other periodical of particular interest is the

New Statesman & Nation (earlier titled

New Statesman & Athenaeum), which Leonard Woolf had been an editor of, and to which he contributed many reviews and essays. Dartmouth College has a complete set of the

New Statesman in all its forms, but copies are in storage, must be requested days in advance, and cannot leave the library.

All of this work could be done, of course, but I determined that it would not be a good use of my time, because much more could be discovered through Woolf’s diaries, letters, and reading notebooks, supplemented by the diaries, letters, and biographies of other writers. (As well as Luedeking and Edmonds’

bibliography of Leonard Woolf, which includes summaries of all of his

NS&N writings — perfectly adequate for my work.)

And so I began work on the spreadsheet. Though I chronicled all of Woolf’s references to her reading from 1930-1938, my own interest was primarily in what contemporary writers she was reading, and how that reading may have affected her conception and structure of

The Years and, to a lesser extent,

Three Guineas (to a lesser extent because her references in that book itself are more explicit, her purpose clearer). As I began the work, I feared I was on another fruitless path. During the first years of the 1930s, Woolf was reading primarily so as to write the literary essays in

The Common Reader, 2nd Series, which contains little about contemporary writing, and from the essays themselves we know what she was reading.

But then in 1933 I struck gold with this entry from 2 September 1933:

I am reading with extreme greed a book by Vera Britain [sic], called The Testament of Youth. Not that I much like her. A stringy metallic mind, with I suppose, the sort of taste I should dislike in real life. But her story, told in detail, without reserve, of the war, & how she lost lover & brother, & dabbled her hands in entrails, & was forever seeing the dead, & eating scraps, & sitting five on one WC, runs rapidly, vividly across my eyes. A very good book of its sort. The new sort, the hard anguished sort, that the young write; that I could never write. (Diary 4, 177)

Vera Brittain’s Testament of Youth was published in 1933, and was one of the bestselling books of the year. It remains in print, and

a film of it was in US theatres this summer. What struck me in Woolf’s response to it was that she called it a book “I could never write” — and she did so just as

The Years was finding its ultimate form in her mind, and only months before she started to write the sections concerned with World War One. What also struck me was that her response to

Testament of Youth was in some ways similar to her infamous response to Joyce’s

Ulysses, a book she thought vulgar and a bit too obsessed with bodily functions, but which also clearly fascinated and

influenced her.

One of the things that occurred to me after reading Woolf’s note on

Testament of Youth was that

The Years is among her most physically vivid novels. Sarah Crangle

has said of it: “

The Years is a culminating point in Woolf ’s representation of the abject, as she incessantly foregrounds the body and its productions” (9). The September 2 diary entry shows that Woolf was highly aware of this foregrounding in Vera Brittain’s (very popular) book, and her framing of herself as part of an older generation and someone unable to write in such a way may have worked as a kind of challenge to herself.

I then sought out

Testament of Youth and read it (all 650 pages) with Woolf in mind. What qualities of this book caused it to run so rapidly across her eyes? She herself wrote in a letter to her friend Ethel Smyth on September 6: “Vera Brittain has written a book which kept me out of bed till I'd read it. Why?” (

Letters 5, 223). I asked

Why? myself quite a bit as I began reading

Testament, because the first 150 pages or so are not anything a contemporary reader is likely to find gripping. And yet reading with Woolf in mind made it quite clear: The first section of

Testament is all about Vera Brittain’s attempt to get into Oxford, and Woolf herself had been denied (because of her gender) the university education her brothers received, a fact that bothered her throughout her life. The ins and outs of Oxford entrance exams may not be scintillating reading for most people, but for a woman who had never even been able to consider taking those exams, and yet dearly yearned for an educational experience of the sort men were allowed,

Testament provides a vivid vicarious experience. The central part of the book, about Brittain’s experience as a nurse during the war, also provided vicarious experience for Woolf, whose own experience of the war was far less immediate. Woolf lost some friends and distant relations in the war (most notably the poet

Rupert Brooke, with whom she was friendly and may have had some romantic feelings for), but did not experience anything like the trauma that Brittain did: the loss of all of her closest male friends, including her fiancé and her brother. Nor did Woolf see mutilated bodies and corpses, as Brittain did.

Woolf and Brittain were very much aware of each other — Brittain, in fact, makes passing mention to

A Room of One’s Own in

Testament of Youth — and

the first book-length study of Woolf in English was written by Brittain’s great friend

Winifred Holtby (an important character in the latter part of

Testament; after Holtby’s death in 1935, Brittain wrote a biography of her titled

Testament of Friendship, which Woolf thought presented too flat a view of Holtby, a person she seems to have come to respect, though she didn’t much like Holtby’s writing). There is, though, very little scholarship on Woolf, Brittain, and Holtby together, perhaps because Brittain and Holtby seem like such different writers from Woolf in that they were much more committed to a kind of social realism that Woolf abjured. There's a lot of work still remaining to be done on the three writers together. Not only is

Testament of Youth a book that can be brought into conversation with

The Years, but Brittain’s novel

Honourable Estate, published one year before

The Years, has numerous similarities in its scope and goals to

The Years, though it seems almost impossible that it had any direct influence, since it was published when Woolf was doing final revisions of

The Years and she didn’t much like Brittain’s writing, so was unlikely to have read the book (I’ve certainly found no evidence that she did).

In the course of this research, I soon discovered that UNH’s own emerita professor Jean Kennard published a book in 1989 titled

Vera Brittain and Winifred Holtby: A Working Partnership, the first (and still only) scholarly study of the two writers together. I read the book avidly, as I had taken a seminar on Virginia Woolf with Prof. Kennard in the spring of 1998 at UNH as an undergraduate, and I owe much of my love of Woolf to that seminar. The book looks closely at each authors’ writings and proposes that their friendship was a kind of lesbian relationship, an idea that has been somewhat controversial (Deborah Gorham’s

study of Brittain offers a nuanced response).

In addition to exploring the connections and resonances between Woolf, Brittain, and Holtby, I looked at three writers of the younger generation whom Woolf knew personally and paid close attention to:

John Lehmann,

William Plomer, and

Christopher Isherwood. Lehmann worked for the Woolfs at their Hogarth Press in the early thirties, left for a while, then returned and took a more prominent role, buying out Virginia Woolf’s share of the press in the late 1930s. Lehmann and the Woolfs had an often contentious relationship, as he was very interested in the work of younger writers, particularly poets, and Virginia Woolf especially had more mixed feelings about the directions that writers such as

W.H. Auden and

Stephen Spender were going in. Woolf wrote a relatively long letter to Spender on 25 June 1935 about his recent collection of criticism,

The Destructive Element, in which she positions her own aesthetics both in sympathy and tension with Spender’s, particularly Spender’s perspective on

D.H. Lawrence.

Spender’s defense of Lawrence helps explain some of Virginia Woolf’s resistance to the younger writer’s aesthetic. One of the insights that my work this summer provided (at least to me) was the extent to which Woolf thought about, and was bothered by, Lawrence, who died in March 1930. (In 1931, Woolf wrote "Notes on D.H. Lawrence", primarily about

Sons and Lovers.) She had complex feelings about Lawrence’s writing — disgust, frustration, and annoyance mixed with fascination. She often said she hadn’t read much of Lawrence’s work, but from the amount of references she makes to it, and the number of critical studies and memoirs about Lawrence that she read and commented on, I don’t think her protestations of not having read much of Lawrence are quite accurate — she was clearly familiar with all his major novels, and I suspect that in her letters she downplayed this familiarity as a hedge against the strong feelings of correspondents who thought Lawrence to be among the greatest British novelists of the age. Lawrence’s work was very much on Woolf’s mind in the first years of the 1930s, and it therefore seems likely to me that

The Years was also conceived as a kind of response to

The Rainbow and

Women in Love in particular. But that's more hunch than anything, and this is a topic for more study.

John Lehmann introduced Christopher Isherwood to the Woolfs, and encouraged them to publish his second novel,

The Memorial, which they did. In 1935, they also published his first Berlin novel,

Mr. Norris Changes Trains (in the US,

The Last of Mr. Norris), then in 1937 his novella

Sally Bowles and in 1939 the interlinked stories of

Goodbye to Berlin (later to be adapted as the play

I Am a Camera and the musical

Cabaret). Isherwood’s experience of Berlin in the 1930s was of particular interest to the Woolfs, who themselves (with some trepidation, given the fact that Leonard was Jewish) traveled through Germany briefly in 193

5 to see the extent of the spread of Nazism.

William Plomer was a writer the Woolfs published in 1926, and who became close friends with Lehmann, Isherwood, Auden, and Spender. Plomer was born to British parents in South Africa, attended schools in England, then returned to Johannesburg, where he finished college and then worked as a farmhand and then with his family at a trading post in Zulu lands. It was there that he wrote

Turbott Wolfe, based partly on his experience at the trading post and partly on his friendships among painters and artists in Johannesburg. He was only 20 years old when he sent it to the Woolfs, and they printed it soon after

Mrs. Dalloway. Leonard was particularly interested in African politics and anti-imperialism, and the novel’s theme of racial mixing as a solution to the tensions between races in South Africa was iconoclastic and proved controversial. Plomer left South Africa and spent time in Japan, experiences which informed his later novel (also published by the Woolfs)

Sado, a story that included homosexual overtones. (Like Lehmann, Isherwood, Auden, and Spender, Plomer was gay, though less openly and comfortably so than his friends.) Plomer would publish a number of books with the Woolfs, including some well-received volumes of poetry, but eventually moved to publish his fiction and autobiographies with Jonathan Cape, where he was an editorial reader (and convinced Cape to publish the first novel of his friend Ian Fleming,

Casino Royale — a very young Fleming, in fact, had written Plomer a fan letter after

reading Turbott Wolfe, the two became friends when Fleming was a journalist in the 1930s, and eventually Fleming dedicated

Goldfinger to Plomer).

Plomer became a more frequent member of the Woolf’s social circle than any other young writer that I’ve noticed, and Virginia Woolf seems to have felt almost motherly toward him. Aesthetically, he was far less threatening than the other young men of the Auden generation, and though his novels can easily be read through a queer frame, he was more circumspect about the topic than his peers.

As the summer wound down and I continued to work through Woolf’s diaries and letters, I became curious about the place of

Elizabeth Bowen’s work in her life. Woolf and Bowen were friends, and Bowen’s work shows many Woolfian qualities, but Woolf made very few conclusive statements about Bowen’s novels that I have been able to find so far — mostly, she acknowledge Bowen sending her each new novel, and always said she would read it soon, but I have only found definite evidence that she read one,

The House in Paris, which is set soon after World War I and, like

Mrs. Dalloway, takes place over the course of a single day. Like the connections and resonances between Woolf, Brittain, and Holtby, the relationship between the works of Woolf and Bowen seems to be ripe for further study.

But the summer has ended, and my studies must now move toward my Ph.D. qualifying exams, so the British writers of the 1930s, as fascinating as they were, must move now to the background as I widen my view toward everything there is to say and know about modernism, postcolonial studies, and queer studies...

Read the rest of this post

There are lots of reasons that the

University of New Hampshire, where I'm currently working toward a

Ph.D. in Literature, should be in the news. It's a great school, with oodles of marvelous faculty and students doing all sorts of interesting things. Like any large institution, it's got its problems (I personally think the

English Department is underappreciated by the Powers That Be, and that the university as a whole is not paying nearly enough attention to the wonderful programs that don't fall under that godawful acronym-of-the-moment

STEM, but of course I'm biased...) Whatever the problems, though, I've been very happy at the university, and I'm proud to be associated with it.

But Donald Trump and Fox News or somebody discovered a guide to inclusive language gathering dust in a corner of the UNH website and decided that this was worth denouncing as loudly as possible, and from there

it spread all over the world. The UNH administration, of course, quickly distanced themselves from the web page and then today it was taken down. I expect they're being honest when they say they didn't know about the page. Most people didn't know about the page. The website has long been rhizomatic, and for a while just finding the academic calendar was a challenge because it was hidden in a forest of other stuff.

I, however,

did know about the page. In fact, I used it with my students and until today had a link to it on my

Proofreading Guidelines sheet. It led to some interesting conversations with students, so I found it a valuable teaching tool. I thought some of the recommendations in the guidelines were excellent and some were badly worded and some just seemed silly to me, like something more appropriate to an

Onion article. ("People of advanced age" supposedly being way better than any other term for our elders reads like a banal parody of political correctness. Also, never ever ever ever call me a "person of advanced age" when I become old. Indeed, I would like to be known as an

old fart. If I manage to achieve elderliness — and it is, seriously, a great accomplishment, as my amazing, 93-year-old grandmother [who calls herself "an old lady"] would, I hope, agree — if I somehow achieve that, then I will insist on being known as an old fart. But if you would rather be called a person of advanced age rather than a senior or an elder or an old fart, then I will respect your wishes.)

The extremity of the guide was actually why I found it useful pedagogically. Inevitably, the students would find some of the ideas ridiculous, alienating, and even angering. That makes for good class discussion. In at least one class, we actually talked about the section that got Donald Trump and Fox and apparently everybody else so upset — the recommendation to be careful with the term "American". Typically, students responded to that recommendation with the same incredulity and incomprehension that Trump et al. did. Understandably so. We're surrounded by the idea that the word "American" equals "United States", and in much usage it does. I sometimes use it that way myself. It's difficult not to. But I also remember a Canadian acquaintance when I was in college saying, in response to my usage, "You know, the U.S. isn't the whole of North America. You just think you are." Ouch. And then when I was in Mexico for a summer of language study, at least one of our teachers made fun of us for saying something like, "Oh, no, I'm not from Mexico, I'm from America!"

We don't have another good noun/adjective for the country (United Statesian is so cumbersome!), and the Canadians can say Canadian and the Mexicans can say Mexican and so we kind of just fall back on

American. And have for centuries. So it goes. But it's worth being aware that some people don't like it, because then as a writer or speaker you can try to be sensitive to this dislike, if being sensitive to what people dislike is important to you.

This and other recommendations in the guidelines lead to valuable discussion with students because such discussion helps us think more clearly about words and language. The guide had some helpful guidance about other things that people might take offense to, whether the gentle, somewhat mocking offense of my Canadian acquaintance and Mexican teachers, or more serious, deeper offense over more serious, deeper issues.

It all comes down to the two things that govern so many writing tasks: purpose and audience. (When I'm teaching First-Year Composition, I always tell them on the first day that by the end of the course they'll be very tired of hearing the words

purpose and

audience.) If your purpose is to reach as wide an audience as possible, then it's best to try to avoid inadvertently offending that audience. Just ask anybody in PR or marketing who didn't realize their brilliant idea would alienate a big, or at least vocal, section of the audience for whatever they were supposed to sell. Ultimately, you can't avoid offending everybody — indeed, it's hardly desireable, as some people probably deserve to be offended — but what offends different people (and why) is useful knowledge, I think. In any case, it's much better to be offensive when you're trying to be offensive than when you're not trying to be and discover much to your surprise, embarrassment, and perhaps horror, that you actually are. (As we used to say [before we were people of advanced age]: been there, done that.)

Advice about inclusive language is similar to advice I give about grammar and spelling errors. All of my students should know by the time they've had me as a teacher that the prohibitions against such things as splitting infinitives or ending sentences with prepositions or starting sentences with conjunctions or any number of other silly rules are just that: silly. They often lead to bad writing, and their usefulness is questionable at best. However, I think every writer should know and understand all the old and generally silly prohibitions. Why? Because you will, at some point in your life, encounter someone who really, deeply cares. And you should be able to explain yourself, because the person who really, deeply cares might be somebody you want to impress or convince about something.

In fact, that's why I give my students my long and probably very boring proofreading guide. I want them to impress me, and I don't want my pet peeves about language and usage to get in the way. (No matter how anti-hierarchical we all might want to be, ultimately I'm the guy responsible for my students' grades, and so it's in their best interests to know what my pet peeves are.) They can dismiss my pet peeves as silly or irrelevant if they want, but they can't say they don't know what they are. Indeed, if I say to a student, "Why did you use 'he/she' when my proofreading guidelines specifically say I would prefer for you not to use that construction in my class," and they respond with a thoughtful answer, I may not be convinced by their logic, but I will be impressed that they gave it thought; if, on the other hand, they respond, "Oh, I didn't read that, even though you said it was important and could affect our grade," then I will not be impressed, and my not being impressed may not be a good thing for their grade. Such is life.

But really my purpose here was just to say that despite all the horrible things said about that poor little language guide, I will miss it. True, it shouldn't have looked so official if it were not (I, too, thought it was pretty official, though clearly it was not binding and was little read). The UNH statement is wrong, though, when it says, "Speech guides or codes have no place at any American university." I don't like the idea of speech codes much, either, because

speech codes sounds punitive and authoritarian, but

guides — well, I like guides. Guides can be useful, especially if you're feeling lost. As a university, we're a big place full of people who come from all over the country and the world, people who have vastly different experiences, people who use language in all sorts of different ways and have all sorts of different feelings about the languages we use. It can be helpful to know that somebody might consider something offensive that I've never even given a second thought to, and helpful to know why that is, so that I can assess how much effort I want to put into rethinking my own language use. The guide to inclusive language had its flaws, certainly, but it was a useful jumping off point for conversation and education. I'll continue to have similar conversations with students (my own proofreading guide has plenty in it to talk about and debate), and will continue to think such conversations are not about somehow curtailing speech, but are in fact about freeing it by empowering speakers to be more aware of what they say and how the words they use affect other people.

It appears that next year I won't be teaching any first-year composition classes at UNH, which will put on hold an experiment I began this past term with FYC. (I'm teaching Literary Analysis this fall and probably a survey course in the spring.) I'll record here some thoughts on that experiment, both for my own future use and in case they are of use or interest to anyone else...

First, I should note the structure of

the first-year writing classes at UNH requires teachers to assign 3 essays (an analytical essay, research essay, and personal essay) and take students through a process of drafting and revising each of those essays. Beyond that, for the most part, teachers are free to design their classes as they choose. (Graduate instructors such as I follow a more prescribed syllabus for our first term, after which we are as free as any other instructor.)

In my first term, I taught the course in the most straightforward, familiar way, and did not give it any sort of theme. The goal of the course is to teach skills more than content, as much as the two can be separated, and I wanted to see what would happen if I gave the students a lot of leeway in what they wrote their papers about. I should have known better. (Seriously, the first thing I ever published about teaching was

a reflection for English Journal on my first year of teaching, and the basic message of it was: the blank slate is death! But I am incapable of learning from past experience, it seems...) The students wrote pretty flat, boring, stilted essays where they attempted rhetorical analysis, they wrote slightly better but mostly not particularly exciting research essays, and they wrote some really interesting personal essays. I found assessing and responding to their writing, even some of the best writing, challenging though because it was all over the place in its purposes and audiences, and my conferences and draft responses to students who wrote about subjects I knew something about were, I thought, pretty different from my responses to students who wrote about things I knew little or nothing about.

As a graduate instructor, I was required to take a course in Teaching College Composition, and for the final research project,

I investigated the use of film analysis in FYC classes (we had to make a Weebly site as part of the course, and I found it a convenient place to park my research). I started out skeptical of the value of film analysis in a comp course, but ended up liking the idea quite a bit, and decided to try an experiment the next term: How little could I change the basic syllabus and yet give the course a film/media/pop culture theme?

The result was

this syllabus. I tried to change as little of the structure and language of my first term as I could, because I really wanted to see if I could stick closely to the skill-based concept of the course while also giving it more focus.

The results were mixed. The most successful parts of the course were the ones that were most completely redesigned. Indeed, I had put most of my energy into reconceiving the analysis essay as an analysis of a single film scene, and it went from being the worst assignment in the course to the best. The research papers were worse this term and the personal essays were roughly the same, perhaps a bit weaker, though that may have been the result of the different mix of students (second term comp is very different from first term: a lot of people taking the course in the second term are ones who actively avoided it before).

I was impressed with the overall quality of work in the scene analyses (the guidelines are on the

syllabus under "Essay #1: Analysis of a Film Scene"), despite many students struggling with it in their first draft. They mostly struggled against the strict definition of a film scene, because they couldn't imagine how they could analyze such a small thing. That's one of the reasons the assignment worked so well: it pushed them into the position of having no choice but to do close analysis, and they learned a lot by working through their frustration. We spent a class talking about how to use images from the films as evidence within the analysis, and how that can often give us new ideas about what to analyze. This turned out to be a valuable technique for many of the students. The final drafts were, on the whole, specific, focused, and thoughtful.

The research papers ended up being disappointing, especially following the triumph of the analytical essays. Though the students did a great job focusing their scene analyses, they weren't able to transfer what they had learned about specificity and focus to the research essays, and I'd put too much faith in their ability to do this. Despite my telling them over and over again that their topics were too broad, only a couple of students were able to find appropriately narrow topics. I liked using

The Craft of Research as a guide to the unit — it's clear and practical, with lots of step-by-step guidelines, and the students found it useful overall, I think, but even following its guidelines, they weren't able to get their topics narrow enough to be able to write papers that weren't full of vagueness, generality, and ridiculously banal statements.

I've talked with colleagues and friends a lot about this, and have come to a few conclusions and ideas for adjustment. First, the next time I teach the course, I'm going to change the name of the assignment. A number of people in the department don't call it

the research essay but rather

a persuasive essay. That makes good sense not because it's a more accurate label, but because it moves it away from the ossified idea of "research" that many students bring with them from high school. The sorts of research we want them to do in college are somewhat different from the sorts of research we ask them to do in high school, but in their first year of college (and maybe later), they work from what they know. Or, rather, from what they think they know. And that's the problem. They succeeded with the analytical essay because they had no frame of reference for the assignment itself, and so they kept going back to the guidelines and kept asking me for more clarity. That was a good thing, a good process. They kept having to measure their writing against the guidelines in a way that they didn't for the research essay, because most of the students already had an idea of what a "research paper" should look like. In fact, one of the best ones I got was by a student who said he'd never had to write a research paper before in his life, and had felt really lost through a lot of it. Some of the worst ones I got were from students who said they'd done such work before.

Second, I'm going to be more strict with topics. In my desire to give the students as much freedom for creativity as possible, I kept definitions of popular culture loose, and let them write about almost anything they wanted. This defeated a lot of the purpose of having a theme. Next time, I will define the realms very specifically. This, too, may help circumvent some of the sense of having done this sort of thing before and knowing how it's done, since none of the students in the course had had to actually research popular culture before. Narrowing down the definition of popular culture for the course will allow me to be more specific in what I tell them about how to research, what resources are useful, etc., and will give them some practice in research within a discipline.

Ideally, the university would require a separate course just on research, perhaps a course within the student's major, or at least within their college (e.g. the College of Liberal Arts, the business college, etc.). Research involves so much more than just writing a paper that it's extremely difficult to cover it even superficially within the short amount of time of a composition course. But we try.

The personal essays weren't terrible, but I again betrayed the theme and often let students stretch the idea of popular culture beyond reason, to their detriment. Because my tendencies at heart are those of an anarchist, I bristle against having any sorts of guidelines for assignments, and feel guilty for imposing them on students. But the realities of a 15-week course that requires multiple drafts of 3 papers really do make it better to have pretty strict thematic guidelines. Or so it seems to me right now. I need to cultivate a better selection of model essays, too, ones that are much more specifically about film, media, and pop culture.

Which brings me to the main textbook,

Signs of Life in the USA. Overall, I like the book, but I'm also not rousingly enthusiastic about it. Partly, that's the fault of the type of experiment I did here. If I were to design the course more to fit the book, rather than try to fit the book into a course for which it was only partly suitable, I would have, I expect, both a better course and a better use of the textbook. This is especially an issue with

Signs of Life because it has a very specific approach, one emphasizing semiotics, and I almost completely ignored that element of the book. To fit the book into a course that is not at least partially about semiotic analysis is to get much less from the textbook than it has to offer. Nonetheless, we made great use of some of the material on analysis of images.

Signs of Life is quite weak on the research side of things. I was able to supplement well with

The Craft of Research, but it would be nice to have more fully and obviously researched essays in it. There's a ton of great research on media and film analysis, and much more could be brought in. By the time I realized this, I just didn't have time myself to dig up stuff that would be useful models for my students. Next time, I certainly will.

Frankly, unless the next edition of

Signs of Life is less specifically about semiotics, I probably won't use it. There's enough excellent material available online and through the databases the university library subscribes to for us really not to have to use a textbook like that at all. I just need the time to gather the material and organize it. That's the value of a textbook for this course, really: to give the teacher a framework to work from and something to fall back on.

While I was teaching this past term, a friend of mine who's in the Composition & Rhetoric Ph.D. program was writing a paper on teachers' uses of popular culture in comp classes, and specifically on the ways that pop culture can be useful or detrimental to a multicultural classroom, and she asked me a bunch of useful questions about how I was approaching the course. Another friend of ours, who is just finishing up her Comp & Rhet Ph.D. and now teaching at a Massachusetts school with a pretty diverse and often low-income population, joined the discussion and offered a very interesting take on

Signs of Life: that it's a difficult book to use with diverse populations, particularly populations with a lot of class diversity. Her school, in fact, has dropped use of the book altogether.

At UNH, we really can assume that most of our students have a lot of experience with things like video games, streaming movies, social media, smart phones. (I had one student write a paper in which in his first draft he asserted that all kids in the US have video game consoles in their houses!) But if I consider using

Signs of Life again, I'll certainly want to put it through a much tighter evaluative lens, specifically thinking about what its materials assume and expect of students' access to media. I really haven't come to a conclusion about that except that. I do know, though, that it would certainly be nice if the book included essays by writers of significantly less privileged class backgrounds — Dorothy Allison's

"A Question of Class" would be a good place to start...

Which reminds me that one of the interesting questions my friend asked was about my use of LGBTQ texts in class, since I have already, apparently, become known for this in the department. (Probably because I spoke up in Teaching College Comp against the use of the "his/her" construction, one I see as setting up a false binary between men and women and erasing the spectrum of gender identities.) I'll end these reflections, then, with some of the material from my reply that seems worth keeping:

I haven't really gone out of my way in 401 to use LGBTQ texts, though I have in other classes. But they're certainly there. Both terms in 401, I've used David Sedaris, and in both pieces ("Now We Are Five" and "Six to Eight Black Men") he mentions his boyfriend, Hugh. One day at the beginning of the personal essay unit this term, I read aloud to the class an essay by Gwendolyn Ann Smith, founder of the Trans Day of Remembrance, called "We're All Someone's Freak" from the book Gender Outlaws edited by S. Bear Bergman and Kate Bornstein. It's a really fun, accessible essay that serves all sorts of purposes, from showing that "normal" is a power construction, that trans identity is not monolithic, and that people are complex. I completely stumbled on using it when I was desperate for a simple introductory activity that wouldn't last more than 10 minutes, and I think I'll probably make it a more formal part of future 401 classes I teach. We didn't discuss the issues in the piece, though I could tell that some of the students were immediately uncomfortable the minute I read the first sentence and they heard the word "transgender". I directed their attention toward the idea of everybody being somebody's freak, which was the idea I wanted them to think about for their personal essays as they considered point of view: basically, whose freak are you, and why? There wasn't time to get into the material as trans-specific material. Most students lack the vocabulary to talk about trans stuff, so it takes some preparation, but it's worthwhile, and because I think this essay is useful, I'll probably figure out a way to do that preparation in the future. I often used GLAAD's media reference guides on transgender issues, especially the glossary, which gives good, succinct definitions and also a great explanation of terms that are problematic and terms that are outright derogatory.

In the past, I've used all sorts of LGBTQ texts. I try to build something into every course, even if it's just something short, in the same way that I try to get somewhat of a gender balance among the authors and to include material from people of various ethnicities, races, nationalities, backgrounds. (Nothing makes the limits of 15 weeks more apparent!) I do it partly for all the basic reasons any liberal-minded person would, but also because one of the big, sometimes unconscious, motivations for me as a teacher is that I want to be a teacher I would have benefitted from having when I was a student. I think I've built up for myself over the years a pretty good apparatus to overcome initial, atavistic instincts and to wade through the swamp of toxic discourse we all inhabit. I hope to help students do some of the work to do the same. Certainly, I want to make my classroom a comfortable place for all types of people, all types of background, and I hope my students can see themselves reflected in at least some of what we do ... but I also want to make sure that people who have somewhat similar backgrounds to mine don't only see themselves. The world's much more interesting and marvelous that way.

Posting has been nonexistent here for a bit because not only is it the start of a new school year (a time when posting is always light here), but, as I've mentioned before, I'm also now beginning the

PhD in Literature program at the University of New Hampshire. This not only involves lots of time in classes, time teaching

First-Year Writing, and time doing homework and class prep, but I'm also driving over 300 miles a week commuting to and from campus. And of course there are also the inevitable writing projects — currently, I'm writing an introduction for a new translation from the Japanese of a very interesting novel (more on that later, I'm sure), a couple of book reviews and review-essays and essay-essays, a couple of short stories, and the always very slowly progressing book manuscript on 1980s action movies. And I've got a couple video essays I want to make in the next month or so. And I'm editing a short film I shot this summer. And, well, naturally, blogging is not really at the forefront of my mind right now. But it is there, somewhere, in amidst everything else in that rattletrap of a mind.

|

| Me & my pal Jacques |

I've been wondering, too, what exactly to write about the whole PhD thing. For instance, the first question that occurs to people when I say I'm doing this thing at my advanced age:

For god's sake WHY? My answer is simple and honest: They're giving me health insurance and a teaching stipend, which is actually a step up for me, since the stipend is a few hundred dollars more than I made teaching as an adjunct, and now I won't have to pay for my own health insurance. So I actually make more money now as a graduate student than I did as a college teacher. (Welcome to the topsy-turvy world of higher ed!) And I only have to teach one class per term and I get to take classes where I get to read a lot and write a lot and talk about, you know, litritcher. What's not to like? Of course, I know as well as anybody that the last thing the world wants is another lit PhD, and there are no jobs, and even if there are jobs the tenure track is disappearing rapidly and adjunctification is the name of the game in higher ed, and all that jazz. I know. Boy, do I know! It's entirely possible and even likely that I will never get a full-time job on the tenure track. But I honestly don't even know if I

want a full-time job on the tenure track, or if I want to stay in college teaching at all. I'm very conflicted about that. But I'm not conflicted about the stuff I really do love: I love the research, I love academic conversations, I love reading complex and difficult stuff. And for a little while, that's what I'll get to do. I'm not going into any financial debt to do it, so I figure it's about as good a plan as anything else. I'm still open to marrying a successful investment banker, winning the lottery, and/or discovering I'm the lost heir of a billionaire. But this will do for now.

The other thing I wonder about is how much I should write about the progress of my classes and research. For now, I'm not really going to write a lot about it. This term, I'm only able to take one literature class because I also have to take a course on teaching college composition. I can't pretend to enjoy that part of this. All the Composition & Rhetoric people are lovely and brilliant, but I am very much not a Comp/Rhet person. Really, I think I've got more affinity for mechanical engineering than I do Comp/Rhet. I'm glad there are people out there doing it, because it can really be noble work, but I don't know of another field in the discipline of English about which I am less interested, so surviving 30+ hours of it during orientation and now 3 hours/week of it for class, plus teaching the First Year Writing course, is nearly enough to make me rush home and do math problems for fun.

The literature class I have this term is on trauma theory, which I didn't even know was a thing until fairly recently. I've generally avoided psychological approaches to literature, and so this is an interesting foray outside my comfort zone. I would be deeply, deeply surprised if it makes me more fond of psychological approaches to literature than I have been in the past, but it's a provocative class and I think I will at least get a good paper on Coetzee's

In the Heart of the Country out of it. We'll see. First, I have to survive reading Freud, a writer I sometimes find really quite hilarious, but other people apparently take him seriously and therefore don't appreciate my giggles. (Pause for a passage from Deleuze & Guattari's

A Thousand Plateaus, as translated by Brian Massumi: "That day, the Wolf-Man rose from the couch particularly tired. He knew that Freud had a genius for brushing up against the truth and passing it by, then filling the void with associations. He knew that Freud knew nothing about wolves, or anuses for that matter. The only thing Freud understood was what a dog is, and a dog's tail. It wasn't enough. It wouldn't be enough.")

What I'm most enjoying, honestly, is having access to a nice big library every day. I love Plymouth State's

Lamson Library beyond all others, because it was my savior as a child and then over the last five years I've been able to cajole and harangue the librarians into buying lots of books and movies that were of vital interest to me, so the collection now bears quite a bit of my imprint. But Plymouth doesn't have the resources of UNH, and so I already have piles of books on all sorts of different subjects checked out, because I easily get bibliographic whims — for instance, a sudden desire to read all of

Donna Haraway. Many of my happiest hours working on my master's at Dartmouth were spent in the

library there, a library I still return to at least a few times a year.

Is it any surprise, then, that I'm doing a PhD? The only surprise is that it took me this long to get organized enough to do it. After all, I'm really not fit for any other sort of endeavor!