new posts in all blogs

Viewing: Blog Posts Tagged with: inflation, Most Recent at Top [Help]

Results 1 - 6 of 6

How to use this Page

You are viewing the most recent posts tagged with the words: inflation in the JacketFlap blog reader. What is a tag? Think of a tag as a keyword or category label. Tags can both help you find posts on JacketFlap.com as well as provide an easy way for you to "remember" and classify posts for later recall. Try adding a tag yourself by clicking "Add a tag" below a post's header. Scroll down through the list of Recent Posts in the left column and click on a post title that sounds interesting. You can view all posts from a specific blog by clicking the Blog name in the right column, or you can click a 'More Posts from this Blog' link in any individual post.

By: KatherineS,

on 10/7/2016

Blog:

OUPblog

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

statistics,

Data,

Mathematics,

numbers,

physics,

Very Short Introductions,

temperature,

mass,

measurement,

inflation,

*Featured,

Physics & Chemistry,

Science & Medicine,

Health & Medicine,

David J. Hand,

Measurement: A Very Short Introduction,

VSI 500,

measuring instruments,

pragmatic measurement,

representational measurement,

scientific measurement,

Add a tag

My first degree was in mathematics, where I specialised in mathematical physics. That meant studying notions of mass, weight, length, time, and so on. After that, I took a master’s and a PhD in statistics. Those eventually led to me spending 11 years working at the Institute of Psychiatry in London, where the central disciplines were medicine and psychology. Like physics, both medicine and psychology are based on measurements.

The post Measuring up appeared first on OUPblog.

By: Yasmin Coonjah,

on 1/6/2016

Blog:

OUPblog

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

exchange rates,

2016,

interest rates,

energy markets,

economic trends,

economic statistics,

brexit,

oil prices,

monetary policies,

oil market,

Books,

charts,

economy,

US Elections,

inflation,

euro,

david cameron,

*Featured,

Business & Economics,

US economy,

Federal Reserve,

European Central Bank,

Economic Policy with Richard S. Grossman,

unemployment data,

Add a tag

Economists are better at history than forecasting. This explains why financial journalists sound remarkably intelligent explaining yesterday’s stock market activity and, well, less so when predicting tomorrow’s market movements. And why I concentrate on economic and financial history. Since 2015 is now in the history books, this is a good time to summarize a few main economic trends of the preceding year.

The post Economic trends of 2015 appeared first on OUPblog.

By: Yasmin Coonjah,

on 12/9/2015

Blog:

OUPblog

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

Books,

recession,

economic crisis,

GDP,

President Obama,

inflation,

*Featured,

Business & Economics,

Federal Reserve,

Economic Policy with Richard S. Grossman,

FOMC,

interest rates,

Federal Open Market Committee,

Federal Reserve policy,

Federal Reserve System,

financial crisis 2008,

Great Recession,

inflation hawks,

Janet Yellen,

Stanley Fischer,

US recession,

Add a tag

Seven years ago this month the federal funds rate—a key short-term interest rate set by the Federal Reserve—was lowered below 0.25%. It has remained there ever since.Lowering the fed funds rate to rock-bottom levels did not come as a surprise. The sub-prime mortgage crisis led to a severe economic contraction, the Great Recession, and Federal Reserve policy makers used low interest rates—among other tools—in an effort to revive the economy.

The post Birdwatching at the Federal Reserve appeared first on OUPblog.

By: DanP,

on 8/27/2014

Blog:

OUPblog

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

Books,

debt,

economy,

Europe,

inflation,

economists,

*Featured,

Business & Economics,

debt crisis,

old europe,

European economy,

brian pinto,

exchange rates,

how does my country grow?,

new europe,

state owned enterprises,

Add a tag

Bliss was it in that dawn to be alive

But to be young was very heaven!

– William Wordsworth on the French Revolution

I was not that young when New Europe’s transition began in 1989, but I was there: in Poland at the start of the 1990s and in Russia during its 1998 crisis and after, in both cases as the resident economist for the World Bank. This year is the 25th anniversary of New Europe’s transition and the sixth year of Old Europe’s growth-cum-sovereign debt crisis. Old Europe can learn from New Europe: first, about getting government debt dynamics under control if you want growth. Second, about implementing the policy trio of hard budgets, competition and competitive real exchange rates to keep debt dynamics under control and get growth. The contrasting experiences of Poland and Russia underline these lessons (Andrei Shleifer’s take on the transition lessons can be found here).

Poland started with a big bang in 1990, but ran into political roadblocks on the privatization of large state enterprises. It achieved single-digit inflation only in 1998. Between 1995 and 1998, Russia did the opposite. By early 1998, privatization was done and single-digit inflation achieved. But while Poland started growing in 1992 and has one of the most enviable growth records in Europe, Russia suffered a huge crisis in August 1998 after which it was forced to adopt the same policy agenda as Poland.

The first difference is that Poland quickly established fiscal discipline and capitalized on the debt reduction it received from the Paris and London Clubs to get government debt dynamics under control. Russia lost control over its government debt dynamics even as the central bank obsessively squeezed inflation out.

The second difference is that Poland instantly hardened budgets by slashing subsidies to state-owned enterprises (SOEs) and subsequently restricting bank lending to loss-making SOEs. It summarily increased competition by liberalizing imports, but was careful to avoid a large real appreciation by devaluing the zloty 17 months after the big bang, and then moving to a flexible exchange rate. The first two elements of this micropolicy trio, hard budgets and competition, forced SOEs to raise efficiency even before privatization. The third, competitive real exchange rates, gave them breathing space. Indeed, SOEs were in the forefront of the economic recovery which began in late 1992, ensuring that debt dynamics would remain sustainable. This does not mean privatization was irrelevant: SOE managers were anticipating it and expecting to benefit from it; but the immediate spur was definitely the micropolicy trio.

In contrast, Russia’s privatized manufacturing companies were coddled by budgetary subsidies and large subsidies implicit in the noncash settlements for taxes and energy payments that sprouted as real interest rates rose to astronomical levels. Persistent fiscal deficits and low credibility pushed nominal interest rates sky high even as the exchange rate was fixed in 1995 to bring inflation down. The resulting soft budgets, high real interest rates and real appreciation made asset stripping easier than restructuring enterprises, killing growth. Tax shortfalls became endemic, forcing increasingly expensive borrowing that placed government debt on an explosive trajectory and made the August 1998 devaluation, default and debt restructuring inevitable. But this shut the country out of the capital markets, at last hardening budgets. The real exchange rate depreciated massively, leading to a 5% rebound in real GDP in 1999 (against initial expectations of a huge contraction) as moribund firms became competitive and domestic demand switched from imports to domestic products. This policy mix was maintained after oil prices recovered in 2000, ensuring sustainable debt dynamics.

Old Europe, especially the periphery, can learn a lot from the above. Take Italy. By 2013, its real exchange rate had appreciated over 3% relative to 2007, while real GDP had contracted over 8%. The government’s debt-to-GDP ratio increased by 30 percentage points (and is projected to climb to 135% by the end of this year), while youth unemployment went from 20% to 40% over the same period! Italy has no control over the nominal exchange rate and lowering indebtedness through fiscal austerity will worsen already weak growth prospects. Indeed, Italy has slipped back into recession in spite of interest rates at multi-century lows and forbearance on fiscal austerity.

The counter argument is that indebtedness and competitiveness don’t look that bad for the Eurozone as a whole. However, this argument is vacuous without debt mutualisation, a fiscal union and a banking union with a common fiscal backstop, the latter to prevent individual sovereigns, such as Ireland and Spain, from having to shoulder the costs of fixing their troubled banks; the recent costly bailout of Banco Espirito Santo by Portugal is a timely reminder. Besides, Germany has to be willing to cross-subsidize the periphery. Even then, this would only be a start. As a recent IMF report warns, the Eurozone is at risk of stagnation from insufficient demand (linked to excessive debt), a weak and fragmented banking system and stalled structural reform required for increasing competition and raising productivity. Debtor countries are hamstrung by insufficient relative price adjustment (read “insufficient real depreciation”).

The corrective agenda for the Eurozone has much in common with the “debt restructuring-cum-micro policy trio” agenda emerging from the Polish and Russian transition experience. The question is whether the Eurozone can have meaningful growth prospects based on banking and structural reform without an upfront debt restructuring. The answer from New Europe’s experience is “No.” Debt restructuring will result in a temporary loss of confidence and possibly even a recession; but it will also lead to a large real depreciation and harden budgets, spurring governments to complete structural reform, thereby laying the foundation for a brighter future. The key is not the debt restructuring, but whether government behaviour changes credibly for the better following it. As the IMF report observes, progress “may be prone to reform fatigue” with the rally in financial markets. In other words, the all-time lows in interest rates set in train by ECB President Draghi’s July 2012 pledge to do whatever it takes to save the euro is fuelling procrastination even as indebtedness grows and growth prospects dim. Rising US interest rates as the recovery there takes hold and the growing geopolitical risk over Ukraine, which will hurt the Eurozone more than the US, only worsen the picture. The Eurozone has a stark choice: take the pain now or live with a stagnant future, meaning its youth have fewer jobs today and more debt to pay off tomorrow.

The post What can old Europe learn from new Europe’s transition? appeared first on OUPblog.

By: DanP,

on 7/2/2014

Blog:

OUPblog

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

Business & Economics,

eurozone,

liberal party,

Richard S. Grossman,

Irish Potato Famine,

Economic Policy with Richard S. Grossman,

Nine Economic Disasters,

corn laws,

euro crisis,

john russell,

potato famine,

robert peel,

Books,

History,

Economics,

Current Affairs,

economy,

Europe,

famine,

inflation,

irish famine,

Editor's Picks,

*Featured,

currency,

Add a tag

By Richard S. Grossman

What do the Irish famine and the euro crisis have in common?

The famine, which afflicted Ireland during 1845-1852, was a humanitarian tragedy of massive proportions. It left roughly one million people—or about 12 percent of Ireland’s population—dead and led an even larger number to emigrate.

The euro crisis, which erupted during the autumn of 2009, has resulted in a virtual standstill in economic growth throughout the Eurozone in the years since then. The crisis has resulted in widespread discontent in countries undergoing severe austerity and in those where taxpayers feel burdened by the fiscal irresponsibility of their Eurozone partners.

Despite these widely differing circumstances, these crises have an important element in common: both were caused by economic policies that were motivated by ideology rather than cold hard economic analysis.

The Irish famine came about when the infestation of a fungus, Phythophthora infestans, led to the decimation of the potato crop. Because the Irish relied so heavily on potatoes for food, this had a devastating effect on the population.

At the time of the famine, Ireland was part of the United Kingdom. Britain’s Conservative government of the time, led by Prime Minister Sir Robert Peel, swiftly undertook several measures aimed at alleviating the crisis, including arranging a large shipment of grain from the United States in order to offer temporary relief to those starving in Ireland.

More importantly, Peel engineered a repeal of the Corn Laws, a set of tariffs that kept grain prices high. Because the Corn Laws benefitted Britain’s landed aristocracy—an important constituency of the Conservative Party, Peel soon lost his job and was replaced as prime minister by the Liberal Party’s Lord John Russell.

Russell and his Liberal Party colleagues were committed to an ideology that opposed any and all government intervention in markets. Although the Liberals had supported the repeal of the Corn Laws, they opposed any other measures that might have alleviated the crisis. Writing of Peel’s decision to import grain, Russell wrote: “It must be thoroughly understood that we cannot feed the people. It was a cruel delusion to pretend to do so.”

Contemporaries and historians have judged Russell’s blind adherence to economic orthodoxy harshly. One of the many coroner’s inquests that followed a famine death recommended that a charge of willful murder be brought against Russell for his refusal to intervene in the famine.

The euro was similarly the result of an ideologically based policy that was not supported by economic analysis.

In the aftermath of two world wars, many statesmen called for closer political and economic ties within Europe, including Winston Churchill, French premiers Edouard Herriot and Aristide Briand, and German statesmen Gustav Stresemann and Konrad Adenauer.

The post-World War II response to this desire for greater European unity was the European Coal and Steel Community, the European Economic Community, and eventually, the European Union each of which brought increasingly closer economic ties between member countries.

By the 1990s, European leaders had decided that the time was right for a monetary union and, with the Treaty of Maastricht (1993), committed themselves to the establishment of the euro by the end of the decade.

The leap from greater trade and commercial integration to a monetary union was based on ideological, rather than economic reasoning. Economists warned that Europe did not constitute an “optimal currency area,” suggesting that such a currency union would not be successful. The late German-American economist Rüdiger Dornbusch classified American economists as falling into one of three camps when it came to the euro: “It can’t happen. It’s a bad idea. It won’t last.”

The historical experience also suggested that monetary unions that precede political unions, such as the Latin Monetary Union (1865-1927) and the Scandinavian Monetary Union (1873-1914), were bound to fail, while those that came after political union, such as those in the United States in 18th century, Germany and Italy in the 19th century, and Germany in the 20th century were more likely to succeed. The various European Monetary System arrangements in the 1970s, none of which lasted very long, also provided evidence that European monetary unification was not likely to be smooth.

Concluding that it was a mistake to adopt the euro in the 1990s is, of course, not the same thing as recommending that the euro should be abandoned in 2014. German taxpayers have every reason to resent the cost of supporting their economically weaker—and frequently financially irresponsible—neighbors. However, Germany’s prosperity rests in large measure on its position as Europe’s most prolific exporter. Should Germany find itself outside the euro-zone, using a new, more expensive German mark, German prosperity would be endangered.

What we can say about the response to the Irish Famine and the decision to adopt the euro is that they were made for ideological, rather than economic reasons. These—and other episodes during the last 200 years—show that economic policy should never be made on the basis of economic ideology, but only on the basis of cold, hard economic analysis.

Richard S. Grossman is a Professor of economics at Wesleyan University in Connecticut, USA and a visiting scholar at Harvard University’s Institute for Quantitative Social Science. His most recent book is WRONG: Nine Economic Policy Disasters and What We Can Learn from Them. His homepage is RichardSGrossman.com, he blogs at UnsettledAccount.com, and you can follow him on Twitter at @RSGrossman. You can also read his previous OUPblog posts.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only business and economics articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Image credits: (1) Irish potato famine, Bridget O’Donnel. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons. (2) Sir Robert Peel, portrait. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

The post The danger of ideology appeared first on OUPblog.

By: Alice,

on 6/4/2014

Blog:

OUPblog

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

Books,

Current Affairs,

unemployment,

inflation,

Wrong,

*Featured,

Business & Economics,

Richard S. Grossman,

Economic Policy with Richard S. Grossman,

economic indicators,

jobs report,

Nine Economic Disasters,

unemployment data,

unrate,

grossman,

statistic,

Add a tag

By Richard S. Grossman

For the past half dozen years or so, the first Friday of the month has brought fear and dread to large portions of the United States. This heightened anxiety has nothing to do with the phases of the moon, the expiration of multiple financial derivatives, or concerns about not having a date for the weekend. No, at 8:30 am (Eastern Time) on the first Friday of each month, the US Bureau of Labor Statistics releases the unemployment data for the previous month.

The release of the unemployment data sets off a media frenzy, as pundits speculate on the winners and losers. What do the numbers foreshadow for the economy? Have we put the Great Recession behind us? How will Wall Street receive the news? And, perhaps most importantly, how does it affect the Administration’s popularity?

There are plenty of reasons why unemployment should be the “marquee” economic statistic. Unlike other important economic indicators, such as GDP, exports, and new housing starts, the human cost of unemployment is inescapable. On an aggregate level, every tenth of a percent increase in the unemployment rate represents about an additional 200,000 people out of work. It is a lot tougher to conjure up a picture of a 1.2 percent decline in GDP.

On the personal level, when unemployment touches our family, friends, and neighbors, it is hard to ignore.

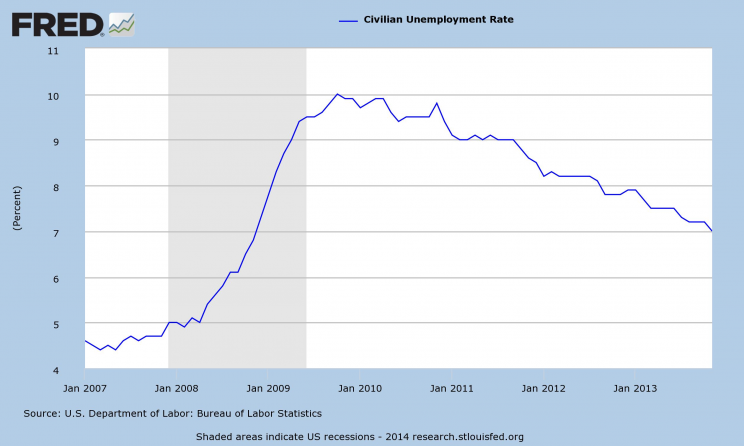

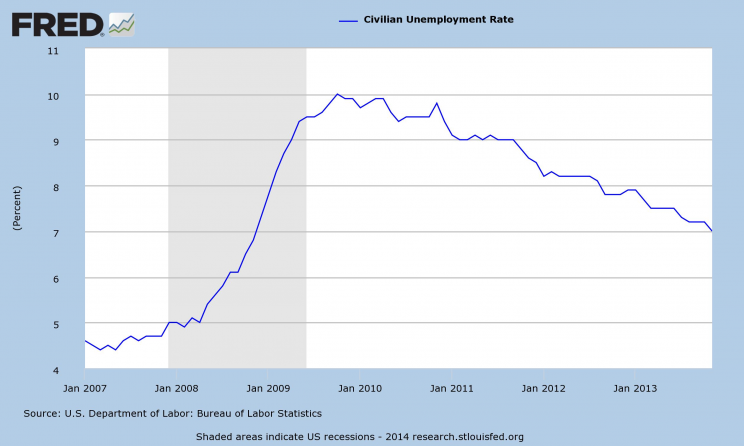

The unemployment rate has been at the center of a monthly drama since the beginning of the Great Recession. As the economy worsened, the unemployment rate surged upward until it hit 10% of the workforce in October 2009, its highest rate in more than 25 years.

Data Source: FRED, Federal Reserve Economic Data, Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis: Civilian Unemployment Rate (UNRATE); US Department of Labor: Bureau of Labor Statistics; accessed 19 May 2014.

With each uptick in unemployment, political analysts wondered out loud if the bad news spelled the failure of the Obama presidency…or the lengthening of the odds against his chances at a second term. For the Administration’s part, the chair of the President’s Council of Economic Advisors typically puts out a statement by 9:30 am on the day of the release, putting the best spin possible on the unemployment data.

Although the unemployment numbers have been and will remain an important economic indicator, in recent months their importance is being overshadowed by another statistic: inflation. There are a couple of reasons for this.

First, even though the unemployment rate has fallen consistently since November 2010, when it was 9.8%, until April 2014, when it was 6.3%, it is clear that the economy has not fully recovered from the Great Recession. Wage growth is anemic; there are still an alarming number of discouraged workers (who are no longer counted as unemployed because they have given up looking for work); and GDP growth is sluggish.

Second, despite the continuing weakness in the economy, lower unemployment has raised concerns that that the economy is overheating. Declining unemployment combined with several years of monetary stimulus via quantitative easing and other unconventional methods has led to concerns that inflation may emerge at any moment.

So far, there is little evidence that we are experiencing a sharp upturn in inflation. Nonetheless, concern that emerging inflation will force the Fed to undertake contractionary monetary policy which, in turn, may have adverse effects for both the high flying stock market and the still low flying economy, are now gaining ground.

Don’t expect the unemployment rate to sink into obscurity anytime soon. It has always been an important indicator of the health of the economy and will remain so. Just be prepared for a second media frenzy around the middle of each month—when the inflation indices are released.

Richard S. Grossman is Professor of Economics at Wesleyan University and a Visiting Scholar at the Institute for Quantitative Social Science at Harvard University. He is the author of WRONG: Nine Economic Policy Disasters and What We Can Learn from Them and Unsettled Account: The Evolution of Banking in the Industrialized World since 1800. His homepage is RichardSGrossman.com, he blogs at UnsettledAccount.com, and you can follow him on Twitter at @RSGrossman. You can also read his previous OUPblog posts.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only business and economics articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

The post Changing focus appeared first on OUPblog.