new posts in all blogs

Viewing: Blog Posts Tagged with: Pub year: 2015, Most Recent at Top [Help]

Results 1 - 21 of 21

How to use this Page

You are viewing the most recent posts tagged with the words: Pub year: 2015 in the JacketFlap blog reader. What is a tag? Think of a tag as a keyword or category label. Tags can both help you find posts on JacketFlap.com as well as provide an easy way for you to "remember" and classify posts for later recall. Try adding a tag yourself by clicking "Add a tag" below a post's header. Scroll down through the list of Recent Posts in the left column and click on a post title that sounds interesting. You can view all posts from a specific blog by clicking the Blog name in the right column, or you can click a 'More Posts from this Blog' link in any individual post.

E. K. Johnson's Prairie Fire is the sequel to The Story of Owen. Both are works of fantasy for young adults that are also described as alternative histories. Here's the synopsis for The Story of Owen:

"Listen! For I sing of Owen Thorskard: valiant of heart, hopeless at algebra, last in a long line of legendary dragon slayers. Though he had few years and was not built for football, he stood between the town of Trondheim and creatures that threatened its survival. There have always been dragons. As far back as history is told, men and women have fought them, loyally defending their villages. Dragon slaying was a proud tradition. But dragons and humans have one thing in common: an insatiable appetite for fossil fuels. From the moment Henry Ford hired his first dragon slayer, no small town was safe. Dragon slayers flocked to cities, leaving more remote areas unprotected. Such was Trondheim's fate until Owen Thorskard arrived. At sixteen, with dragons advancing and his grades plummeting, Owen faced impossible odds—armed only with a sword, his legacy, and the classmate who agreed to be his bard.

Listen! I am Siobhan McQuaid. I alone know the story of Owen, the story that changes everything. Listen!"

Henry Ford hiring dragon slayers! Cool? I don't know because I didn't read

The Story of Owen. I did, however, read the sequel,

Prairie Fire. Here's the synopsis for it:

Every dragon slayer owes the Oil Watch a period of service, and young Owen was no exception. What made him different was that he did not enlist alone. His two closest friends stood with him shoulder to shoulder. Steeled by success and hope, the three were confident in their plan. But the arc of history is long and hardened by dragon fire. Try as they might, Owen and his friends could not twist it to their will. Not all the way. Not all together. The sequel to the critically acclaimed The Story of Owen.

Prairie Fire is primarily about Owen and Siobhan (who tells the story). Their assignment as dragon slayers is to guard Fort Calgary. As I started to read, I saw a lot of place names specific to First Nations but... no people who are First Nations (that comes later).

Early in the book, there's a reference to Manitoulin, a place that (I think) was destroyed in

The Story of Owen. I read "Manitoulin" and right away wondered if that is a Native place. The answer? Yes. According to the Wikwemikong

website, Manitoulin is home to one of the ten largest First Nations communities in Canada. I understand--of course--that in stories like

Prairie Fire, writers can write what they wish--including wiping out existing places--but when the writer is not Native, and one of the places being wiped out is Native, it too closely parallels recent and ongoing displacements and violence done to Indigenous peoples. As such, I object.

We learn a bit more about Manitoulin when we get to the chapter, The Story of Manitoulin(ish) (p. 55):

Once upon a time, there was a beautiful island where three Great Lakes met. Named for a god, it could well have been the home of one: rolling green hills and big enough that it was dotted by small blue lakes of its own. It was the biggest freshwater island in the world, and Canada was proud to call it ours.

Named for a god? I don't think so. From what I'm learning, it means something like 'home of the ancestors.' I also wondered, as I read that line, who named it Manitoulin? Canadians? Canadians who are "proud to call it ours"? Another big pause for me. I doubt that First Nations people reading

Prairie Fire would be ok with that line.

In

Prairie Fire, we learn that the island, situated between the US and Canada, is inhabitable due to American capitalism (p. 55):

Two whole generations of Canadians grew up, never having set foot on that pristine sand, never staying in those quaint hotels, and never learning to swim in those sheltered bays, but always there was hope that we would someday return.

Hmmm. That sounds to me like White people who are lamenting loss of pristine sand and quaint hotels. Again, no Native people. Kind of shouts privilege, to me. Another place named is Chilliwack, home to the Sto Lo people, but no Sto Lo people are in

Prairie Fire. The chapter, Totem Poles, is unsettling, too. These poles are at Fort Calgary. Siobhan and Owen get there, via train. As they traveled, Siobhan worried that they'd be attacked by dragons (p. 69):

There are any number of American movies about dragon slayers fighting dragons from the tops of trains, but I was quite happy not to be reenacting one. We made it all the way to Manitoba before we even saw a dragon out the window, and it was far enough away that we didn’t have to worry about it.

That reminded me of westerns in which Indians are attacking the trains, and while I don't think Johnston intended us to equate dragons with Indians, I kind of can't help but make that connection when I read that passage. Anyway, as the train nears Fort Calgary, they see a row of metal teeth that stretch up into the air (p. 71):

The metal teeth were the tops of stylized totem poles, taller than the California Redwoods on which they were modeled, and thrusting jagged steel into the bright prairie sunset. Though most of the poles were around the wall of the fort, they were also scattered throughout the city itself, to prevent the dragons from dive-bombing any of the buildings.

One of the dragon slayers thinks they are beautiful, but another says (p. 71):

“They’re probably covered with bird crap up close,” Parker pointed out.

Totem poles hold deep significance to the tribes who create them. I haven't studied Parker as a character, and it may be that he's an unpleasant sort who we readers are expected to dislike, but still... Was that "bird crap" line necessary? And why are totem poles cast as tools of defense in the first place? It reminds me of the United States Armed Services use of names of Native Nations and imagery for weapons of war (examples include the Apache attack helicopter and the tomahawk cruise missile). They--like mascot names--are supposedly conveying some sort of honor, but with victory over a foe the goal, are these honorable things to do?

The book goes on and on like that...

In Disposable Civilians, we read about a dragon called the Athabascan Longtail.

Athabascan's are Native, too. And then there's the chapter called The Story of the Dragon Chinook. For those who don't know, Chinook is also the name of a First Nation. In

Prairie Fire, the Chinook dragons are especially vicious. Their attacks are preceded by smoke. There's more railroad trains in this part of the story. To get railroad tracks laid, the government brings Chinese workers to Canada, "paying them just enough that they might forget about the dragons in the sky" (p. 124). And yes, those Chinese workers are amongst those disposable civilians.

In the Haida Welcome chapter (Owen and Siobhan are visiting Port Edward, on the coast), we get to know a character named Peter and his family. They are Haida. They play drums made of dragon's hearts. There's a stage where they dance. The stage has a row of waist high totem poles (p. 221):

These were wooden poles, traditional and fierce looking, each with painted white teeth inside a grinning mouth and an odd crest upon each head.

Owen, Siobhan, and the others gathered there watch the dancers on stage move in ways that suggest they're in a canoe. Siobhan remembers that the Haida are a sea-going nation. The person in front is their dragon slayer. She throws a rope with a large ring on its end to a dragon. On the fourth throw she catches it, the song and dance change, and the dragon is brought to the totem poles where it lies down, defeated. Owen wonders aloud if the dragon had drowned, and Peter laughs, telling him (p. 222):

“No,” Peter said. “The orcas took care of it.” “The whales?” Owen said. “They’re not called Slayer Whales for nothing,” Peter reminded him.

That part of the story makes me uneasy. What Johnston has done is create what she presents as a Native ceremony or dance. It reminds me of what Rosanne Parry did in

Written In Stone. After that dance part, I quit reading

Prairie Fire. Though I can see why it appeals to fans of stories like this, the erasure of Native peoples, the weaponizing of Native artifacts, and the creation of Native story are serious problems. I cannot recommend

Prairie Fire.

I've never used "absolutely disgusted" in a title before today. There are vile things in the world. Some of them are subtly vile, which makes them dangerous because you aren't aware of what is going into your head and heart.

Some things, like Catherynne M. Valente's Six-Gun Snow White are gratuitously vile. As a Native woman, it is very hard to read it in light of my knowledge of the violence inflicted on Native girls and women--today. Here's the synopsis:

A plain-spoken, appealing narrator relates the history of her parents--a Nevada silver baron who forced the Crow people to give up one of their most beautiful daughters, Gun That Sings, in marriage to him. With her mother s death in childbirth, so begins a heroine s tale equal parts heartbreak and strength. This girl has been born into a world with no place for a half-native, half-white child. After being hidden for years, a very wicked stepmother finally gifts her with the name Snow White, referring to the pale skin she will never have. Filled with fascinating glimpses through the fabled looking glass and a close-up look at hard living in the gritty gun-slinging West, readers will be enchanted by this story at once familiar and entirely new.

There is no redeeming Valente's words. There is nothing she could write, as the book proceeds, that will undo what she says in the first half. I quit.

I don't think this is meant to be a young adult novel but I've seen a colleague in children's literature describe it as "fantastic" which is why I decided I ought to see what it is about. As the synopsis indicates, it is a retelling of Snow White. It was first published in 2013 by Subterranean Press as a signed limited edition (1000 signed and numbered hardcover copies), but is being republished in 2015. This time around, the publisher is Saga Press.

Obviously, I don't recommend it. I've never read anything Valente wrote before. I asked, online, if this is typical of her work, and the reply so far is no. So why did she do this? Why would anyone do this?

Six Gun Snow White is not fantastic. It is not brilliant. It is grotesque. It is so disgusting that I will not sully my blog with actual quotes from the book.

- Valente uses animal-like depictions to describe the main character's genitals. Yes, you read that right, her genitals. Animal-like characteristics are often used in children's literature but none, that I recall, that are anything like these. In children's books, you'll find things like Indians who "gnaw" on bones or have "steely patience, like a wolf waiting." Such descriptions dehumanize us.

- Valente has the stepmother bathe the main character in a milk bath to make her skin lighter in tone, but to do the inside parts of her she shoves the main character's head underneath, which echoes the intents of the boarding schools established in the 1800s. A guiding philosophy was 'kill the Indian/save the man' and the idea of the "civilizing" curriculum was to "hold them under until they are thoroughly soaked in the white man's ways."

- Valente shows the main character and her mother (her mother was Crow) being lusted after, abused, beaten, and violated by white men. This is especially troubling, given the violence and lack of investigation of that violence that we see in the US and Canada.

I suppose all of that is so over-the-top to make a point of some kind, but that point need not be made in the first place. As the title for this post says, I am absolutely disgusted by what I see in

Six Gun Snow White.

Well, I did my annual visit to Barnes and Noble to see what they had on the Thanksgiving shelf. Never a pleasant outing, I hasten to add, but one that I do each year, hoping that there won't be any new books where characters do a Thanksgiving reenactment or play of some kind.

Out this year is Just a Special Thanksgiving by Mercer Mayer. I'll say up front that I do not recommend it. Here's the synopsis:

Little Critter® has charmed readers for over forty years.

Now he is going to have a Thanksgiving he'll never forget! From the school play to a surprise dinner for all of Critterville, celebrate along with Little Critter and his family as they give thanks this holiday. Starring Mercer Mayer's classic, loveable character, this brand-new 8x8 storybook is perfect for story time and includes a sheet of stickers!

If you just look at the cover, you don't see anybody in feathers. You might think they're doing a "just be thankful" kind of story, but nope.

One of the first pages shows Critter and his buddies at school, getting ready for the play.

When it is time for the play, Critter (playing the part of a turkey), freezes and the others look on, worried:

Later, everyone goes to the parade, where Critter ends up on a float:

Pretty awful, start to finish, and I gotta say, too, that I'm disappointed. Though I haven't read a Critter book in a long long time, I do have fond memories of them. I dove into research spaces and see that a colleague, Michelle Abate, has an article about Critter in a 2015 issue of Bookbird. I'm going to see if I can get a copy of it. Course, her article won't have anything about Just a Special Thanksgiving in it, but I'm interested in a researcher's perspective on the series.

Oh, and here's a photo of the display:

I didn't look at each book. Some are familiar from years past, like Pete the Cat in which Pete is shown as Squanto. And there's some messed up images in the Curious George book, too. And Pinkalicious.

If I was buying? I'd get that one on the bottom row: The Great Thanksgiving Escape by Mark Fearing. It is hilarious. That page where the kids run into "the great wall of butts" is priceless! I know my sister's grandson would love that part.

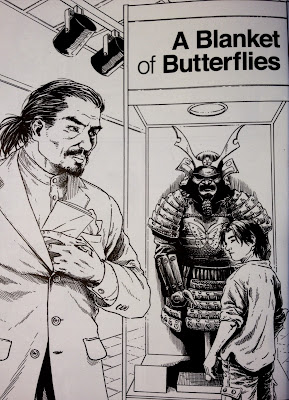

Check out the cover for Richard Van Camp's A Blanket of Butterflies:

Gorgeous, isn't it?

A Blanket of Butterflies, illustrated by Scott B. Henderson, is new this year (2015) from Highwater Press, an imprint of Portage & Main Press in Canada. That sword? It is a key piece of this story.

When you open the cover, here's the first page:

As the story opens, Sonny is at the

Northern Life Museum in Fort Smith, Northwest Territory. He's looking at a samurai suit of armor when he notices a man who is also looking at it. The man's name is Shinobu. See the paper he's pulling from his coat? He's at the museum with a specific purpose: to pick up that suit. It belongs to his family. The museum staff worked to identify who it belongs to, and then got in touch with Shinobu's family.

I gotta say--I love how Van Camp's story gets going--and here's why. So many things in museums are there due to theft and exploitation. Grave robbing of Native graves is rampant. Native protests led Congress to take action. In 1990, Congress wrote the Native American Graves Protection and Repatriation Act to help tribal peoples reclaim remains and artifacts (see the

FAQ). That law, and

A Blanket of Butterflies, is all about dignity and humanity, for all peoples.

Back to the story...

There's something missing from the display. A sword. Shinobu learns where it is and sets out to get it, but Sonny knows where it is, too, and he also knows that it is risky for Shinobu to go there alone. Sonny follows him, and strikes up a conversation, noting that Shinobu has a butterfly tattoo on his hand. Things don't go well. Shinobu gets hurt...

Yesterday (Friday, November 14) I listened to

Acimowin on CJSR, an independent radio station in Edmondton, Canada. The guest? Richard Van Camp. I listened to him talk about

A Blanket of Butterflies and wish you could have heard him, too. There's a grandma in this story. She's the hero. Hearing him talk about her... awesome.

Get a copy of

A Blanket of Butterflies for your library or classroom, or for your own young readers. I really like it and highly recommend it.

And--check out that weekly radio show,

Acimowin, too, on Friday mornings. You can listen online. One of the best things people who write, review, edit, or publish children's and young adult literature can do, is listen to Native voices. Learn who we are, and what we care about. It'll help you do a better job at writing, or reviewing, or editing, or selecting, or... deselecting! Acimowin is hosted by Jojo, who tweets from @acimowin. I laughed out loud more than once, listening to the banter between these First Nations people... (Note: the radio show is not for young kids.) Love the graphics for the show!

Earlier this year, The Case for Loving: The Fight for Interracial Marriage, by Selina Alko, illustrated by Alko and Sean Qualls, was published by Arthur A. Levine Books. It got starred reviews from Kirkus and Publisher's Weekly. The reviewer at Horn Book gave it a (2), which means the review was printed in The Horn Book Magazine.

The review from The New York Times and my review, were mixed, and as I'll describe later, may be the reasons revisions were made to the second printing of the book.

Let's start with the synopsis for The Case for Loving:

For most children these days it would come as a great shock to know that before 1967, they could not marry a person of a race different from their own. That was the year that the Supreme Court issued its decision in Loving v. Virginia.

This is the story of one brave family: Mildred Loving, Richard Perry Loving, and their three children. It is the story of how Mildred and Richard fell in love, and got married in Washington, D.C. But when they moved back to their hometown in Virginia, they were arrested (in dramatic fashion) for violating that state's laws against interracial marriage. The Lovings refused to allow their children to get the message that their parents' love was wrong and so they fought the unfair law, taking their case all the way to the Supreme Court - and won!

On Feb 6, 2015,

The New York Times reviewer, Katheryn Russell-Brown, wrote:

Alko’s calm, fluid writing complements the simplicity of the Lovings’ wish — to be allowed to marry. Some of the wording, though, strikes a sour note. “Richard Loving was a good, caring man; he didn’t see differences,” she writes, suggesting, implausibly, that he did not notice Mildred’s race. After Mildred is identified as part black, part Cherokee, we are told that her race was less evident than her small size — that town folks mostly saw “how thin she was.” This language of colorblindness is at odds with a story about race. In fact, this story presents a wonderful chance to address the fact that noticing race is normal. It is treating people better or worse on the basis of that observation that is a problem.

And on March 18, 2015, I wrote a long review, focusing on Mildred Jeter's identity. I concluded with this:

In The Case for Loving, Alko uses "part African-American, part Cherokee" but I suspect Jeter's family would object to what Alko said. As the 2004 interview indicates, Mildred Jeter Loving considered herself to be Rappahannock. Her family identifies as Rappahannock and denies any Black heritage. This, Coleman writes, may be due to politics within the Rappahannock tribe. A 1995 amendment to its articles of incorporation states that stated (p. 166):

“Applicants possessing any Negro blood will not be admitted to membership. Any member marrying into the Negro race will automatically be admonished from membership in the Tribe.”

I'm not impugning Jeter or her family. It seems to me Mildred Jeter Loving was caught in some of the ugliest racial politics in the country. As I read Coleman's chapter and turn to the rest of her book, I am unsettled by that racial politics. In the final pages of the chapter, Coleman writes (p. 175):

"Of course, Mildred had a right to self-identify as she wished and to have that right respected by others. Nevertheless, viewed within the historical context of Virginia in general and Central Point in particular, ironically, “the couple that rocked courts” may have inadvertently had more in common with their opponents than they realized. Mildred’s Indian identity as inscribed on her marriage certificate and her marriage to Richard, a White man, appears to have been more of an endorsement of the tenets of racial purity rather than a validation of White/ Black intermarriage as many have supposed."

Turning back to The Case for Loving, I pick it up and read it again, mentally replacing Cherokee with Rappahannock and holding all this racial politics in my head. It makes a difference.

At this moment, I don't know what it means for this picture book. One could argue that it provides children with an important story about history, but I can also imagine children looking back on it as they grow up and thinking that they were misinformed--not deliberately--but by those twists and turns in racial politics in the United States of America.

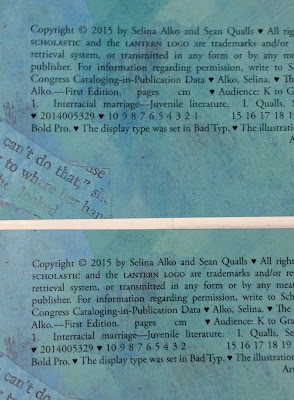

Fast forward to last week (November 4, 2015), when I learned that changes were made to

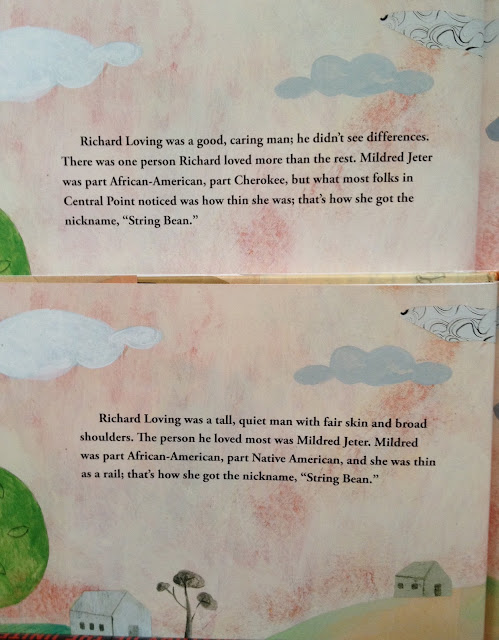

The Case for Loving in its second printing. Here's a photo of the copyright page for the two books. Look at the second line from the bottom in the top image. See the string of numbers that starts at 10 and goes on down to 1? That string is data. The lowest numeral in the string is 1, which tells us that the book with the 1 is the original. Now look at the second line from the bottom in the bottom image. See the string of numbers ends with numeral 2? That tells us that is the 2nd printing.

I learned about the second printing by watching Daniel Jose Older's video,

Full Panel: Lens of Diversity: It is Not All in What You See. Sean Qualls, illustrator of

The Case for Loving was also on that panel, which was slated as an opportunity to talk about Rudine Sims Bishop's idea of literature as windows, mirrors, and doors, framed around Sophie Blackall's art for the New York public transit system. The moderator and panel organizer, Susannah Richards, said that she saw people using social media to say that they thought they say themselves in Blackall's art. (To read more about the discussions of Blackall's picture book,

A Fine Dessert, see

Not recommended: A Fine Dessert.)

At approximately the 34:00 minute mark in Older's video, Richards began to speak about

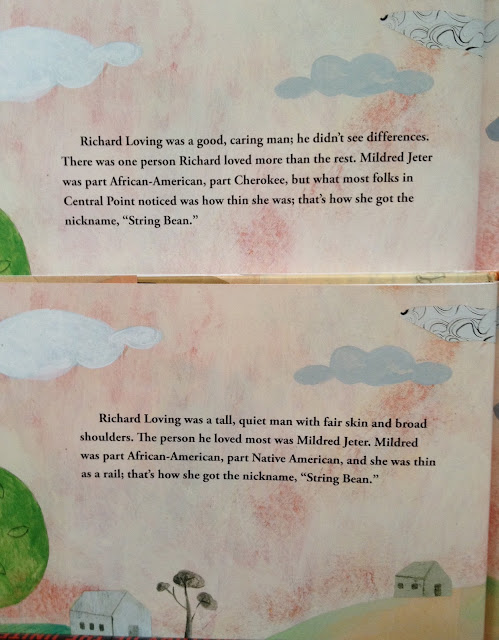

The Case for Loving and how Qualls and Alko addressed concerns about the book. Richards had a power point slide ready comparing a page in the original book with a page in the revised edition. It is similar to the one I have here (in her slide, she has the revised version at the top and the original on the bottom):

Qualls said "So, part of what happened is... There is a page with a description of Mildred and Richard." Qualls then read the revised page and the original one, too: "Richard was a tall quiet man with fair skin and broad shoulders. The person he loved most was Mildred Jeter. Mildred was part African-American, part Native American, and she was thin as a rail; that's how she got the nickname, String Bean. Richard Loving was a good, caring man; he didn't see differences. There was one person Richard loved more than the rest. Mildred Jeter was part African-American, part Cherokee, but what most folks in Central Point noticed was how thin she was; that's how she got the nickname, "String Bean."

|

| Reese's photo of original (on top) and revised (on bottom) page in THE CASE FOR LOVING |

For now, I'm going to step away from the video and Quall's remarks in order to compare the original lines on the page with the revised ones:

(1)

Original: Richard Loving was a good, caring man; he didn't see differences.

Revision: Richard Loving was a tall, quiet man with fair skin and broad shoulders.

See that change? "he didn't see differences" is gone. This, I think, is the result of Russell-Brown (of the

Times) saying that him not seeing difference was implausible, especially since this book is about race.

(2)

Original: There was one person Richard loved more than the rest.

Revision: The person he loved most was Mildred Jeter.

I don't know what that sentence was changed, and welcome your thoughts on it.

(3)

Original: Mildred Jeter was part African-American, part Cherokee...

Revision: Mildred was part African-American, part Native American...

In my review back in March, I said it was wrong to describe her as being part Cherokee, because on the application for a marriage license (dated May 24, 1958), she stated she was Indian. I assume the change to "Native American" rather than "Indian" was done because the person(s) weighing in on the change thought that "Indian" was pejorative. It can be, depending on how it is used, but I use it in the name of my site and it is used by national associations, too, like the National Congress of American Indians or the National Indian Education Association or the American Indian Library Association.

I think it would have been better to use Indian--and nothing else--because that is what Jeter used. "Native American" didn't come into use until the 1970s, as indicated at the Bureau of Indian Affairs website and other sources I checked. In order to tell this story as determined by the Supreme Court case, Alko and Qualls had to include "part African American" because that is the basis on which the case went to the Supreme Court in the first place. I'll say more about all of this below.

(4)

Original: ...but what most folks in Central Point noticed was how thin she was;

Revision: ...and she was thin as a rail;

I think this change is similar to (1). People do notice race.

(5)

Original: ...that's how she got the nickname, "String Bean."

Revision: ...that's how she got the nickname, "String Bean."

No change there, which is fine.

~~~~~~~~~

Now I want to return to the video, and look more closely at (3) -- how Alko and Qualls describe Jeter.

After reading aloud the original and revised passage, Qualls paused. The moderator, Susannah Richards, stepped in. Here's a transcript:

Richards: "Research is complicated, and in researching this particular book, and looking... And even having some of my law friends look at it, they were like 'well some things say she was Cherokee and some things say she was wasn't, some things say her birth certificate said this,' and... There was just a lot of information out there."

Qualls: "Right. And I think that Deborah..."

Richards: "Debbie Reese."

Qualls: "Debbie Reese..."

Richards: "Who many of you may follow on her blog."

Qualls: "Really brought issue with the Cherokee description of Mildred, and, I have spoken to at least some family members and no one really seems to know whether she was Cherokee or Rappahannock. And I think there are some... Debbie Reese may have said, or somewhere I read, that Mildred claimed not to have any African American heritage. But then I've also read that the Rappahannock Nation is less likely to recognize someone as Rappahannock if they claim to have any African American heritage. We're also talking about the 1950s and 1960s where it may have been convenient for someone to claim that they had no African American heritage. James Brown, of all people, claimed he was part Japanese, part Native American, and had no African American heritage. So, it is extremely loaded, and yeah, you know, I really don't know what to say about it. And, it comes down to ones intention, and you know, in trying to represent diversity, and the fact is, no one really knows what her back ground was. I believe that she was part African American. My gut tells me that. She looks that way, she feels that way when I see her, when I see videos of her. So, yeah, that became a little bit of a controversy and was very disturbing to my wife, who is Canadian in origin, and the fact that you're Australian, you know, its very interesting. There are two people that I know that include and have always included African Americans in their art, and without question, that's really important, I think.

Qualls is right, of course. I did raise a question about them identifying Jeter as Cherokee.

I'm curious about his next comment, that he has spoken to family members who say that no one really knows whether she was Cherokee or Rappahannock. In my review, I quoted Coleman's 2004 interview of Jeter, in which she said "I am not Black. I have no Black ancestry. I am Indian-Rappahannock." I didn't include this passage (below) but am including it now--not as a deliberate attempt to argue with Qualls--but because I am committed to helping people understand Native nationhood and how Native people speak of their identity. Coleman writes (p. 173):

The American Indian identity is strong within the Loving family as demonstrated by Mildred’s grandson, Marc Fortune, the son of her daughter Peggy Loving Fortune. When Mildred Loving’s son, Donald, died unexpectedly on August 31, 2000, Marc, according to one attendee, arrived at his uncle’s funeral dressed in native regalia and performed a “traditional Rappahannock” ritual in honor of his deceased uncle. In fact, all of the Loving children are identified as Indian on their marriage licenses. During an interview on April 10, 2011, Peggy Loving stated that she is “full Indian.” This was also the testimony of her uncle, Lewis Jeter, Mildred’s brother who stated during an interview on July, 20, 2011, that the family was Indian and not Black. Echoing his sister’s words he stated, “We have no Black ancestry that I know of.”

Based on all I've read and many conversations with people who do not understand the significance of saying you're a member or citizen of a specific tribe, here's what I think is going on.

In watching videos of Jeter, Qualls said that he believes Jeter was part African American. In the video, he said "She looks that way, she feels that way when I see her, when I see videos of her." He is basing that, I believe, on her

physical appearance rather than on her own words about her citizenship in the Rappahannock Nation. Qualls is conflating a racial identity with a political one.

I'm not critical of Qualls for thinking that way. I think most Americans would think and say the same thing he did. That is because Native Nationhood is not taught in schools. It should be, and it should be part of children's books, too, because our membership or citizenship in our nations is a fact of who we are. Indeed, it is the most significant characteristic of who we are, collectively. It is why our ancestors made treaties with leaders of other nations. It is why we, today, have jurisdiction of our homelands.

All across the U.S., there are peoples of varying physical appearance who are citizens of a Native nation. My paternal grandfather is white. He was not a tribal member. My dad and my uncle are tribal members. Myself and my siblings, though we range in appearance (I have the darkest hair and skin tone amongst us), are all tribal members. On the federal census, we say we're tribal members and we specify our nation as Nambe Pueblo. Our political identity is a Native one. Because of our grandfather, some of us look like we're mixed bloods, because we are, but when asked, we say we are tribal members, and we say that, too, on the U.S. census documents. We were raised at Nambe and we participate in a range of tribally-specific activities, from ceremonies to civic functions such as community work days and elections. What we look like, physically, is not important.

In short, the revision regarding Jeter's identity is based on a physical description rather than a political one. My speculation: the author, illustrator, and their editor do not know enough about Native nationhood to understand why that distinction matters.

Now let's take a look at the content of the reviews.

The reviewers at

School Library Journal, Kirkus echoed the book, saying that Mildred was African American and Cherokee. The reviewer at

Publisher's Weekly did not say anything about her identity. Horn Book's reviewer said "Richard Loving (white) and Mildred Jeter (black) fell in love and married..." Not surprisingly, then, that the Horn Book reviewer tagged it with "African Americans" as a subject, and not Native American, but I'm curious why they ignored her Native identity? Did they choose to view the Loving case as one about interracial marriage between a White man and Black woman--as the Loving's lawyers did? Perhaps.

In Older's video, he says that there are some stories that he wouldn't touch. I think the Loving case is one that is more complicated than a picture book for young children can do justice to. Here's key points, from my point of view:

In the 1950s, Mildred Jeter said she was Indian. We don't know if she said that out of a desire to avoid being discriminated against, or if she said that because she was already living her life as one in which she firmly identified as being Indian. Either way, it is what she said about who she was on the application for a marriage license.

In the 1960s, because Mildred Jeter and Richard Loving's marriage violated miscegenation laws, their case went before the Supreme Court of the United States. To most effectively present their case, the emphasis was on her being Black.

In the 2000s, Jeter and her children said they are Indian, and specified Rappahannock as their nation.

In the 2000s, Alko and Qualls met and fell in love.

In the 2010s, Alko and Qualls worked together on a picture book about the Lovings. In the author's note for

The Case for Loving, Alko said that she's a white Jewish woman from Canada, and that Sean is an African American man from New Jersey. She said that much of her work is about inclusion and diversity and that it is difficult for her to imagine that just decades ago, couples like theirs were told by their governments, that their love was not lawful. For years, Alko writes, she and Qualls had thought about illustrating a book together.

The Case for Loving is that book.

I think it is fair to say that the love they have for each other was a key factor in the work they did on

The Case for Loving, but who they are is not who the Lovings were. That fact meant they could not--and can not--see Mildred for who she is.

My husband and I are also a couple in an interracial marriage. He's White; I'm Native. If we were an author/illustrator couple working in children's books and wanted to do a story about the Lovings, we'd enter it from a different place of knowing. We both know the importance of Native nationhood and the significance of Nambe's status as a sovereign nation. He didn't know much about Native people until he started teaching at Santa Fe Indian School, where we met in 1988 when I started teaching there. What we do not have is a lived experience or knowledge of the life of Mildred Jeter as she lived her life in the 1950s in Virginia. We'd be doing a lot of research in order to do justice to who she was.

At the end of his remarks (in the video) about

The Case for Loving, Qualls said that it comes down to intentions, and that his wife and Sophie Blackall are very careful to include diversity in their work. He said he thinks it is important. I don't think anyone would disagree with that statement. Diversity is important. But, as his other remarks indicate, he's since learned how complicated the discussion of Jeter's identity were, then and now, too. They've revised that page in the book but as you may surmise, I think the revision is still a problem.

I like the art very much and think it is important for young children to know about the Lovings and families in which the parents are of two different demographics. I'll give some thought to how it could be revised so that it sets the record straight, and I welcome your thoughts (and do always let me know--as usual--about typos or parts of what I've said that lack clarity or are confusing).

Pick up a copy of

That the Blood Stay Pure: African Americans, Native Americans, and the Predicament of Race and Identity in Virginia, published in 2013 by Indiana University Press. Read the chapter on the Lovings, and read Alko and Qualls and see what you think. Can it be revised again? How?

The main character in

Whistle is a familiar one. Readers met him before. When Richard Van Camp's

The Lesser Blessed opens, it is the first day of school. Larry, the protagonist is cautious as he makes his way through the building, thinking "I'm Indian and I gotta watch it" (p. 2). One of the people he has to be cautious about is Darcy McMannus. Larry describes Darcy as the "most feared bully in town" (p. 19).

Van Camp's

Whistle is about Darcy--but he's not at school anymore. He's in a detention facility and writing letters to Brody, a character he beat up. The letters to Brody are part of a restorative justice framework for working with youth. I found that I needed time as I read

Whistle. Time to think about Darcy. He felt so real, and people with troubles like his require me to slow down and think about young people.

I highly recommend

Whistle for young adults. Published by Pearson as one of the titles in its

Well Aware series, you can

write to Van Camp and get it directly from him.

(My apologies! I'm behind on writing reviews of the depth that I prefer. Rather than wait, I'm uploading my recommendations and hope to come back later with a more in-depth look.)

Due out from Tradewind Books in Canada in 2015 is Tara White's

Where I Belong. The main character is Carrie, a teen with black hair and dark skin who was adopted by a white couple.

Here's the synopsis:

This moving novel of self-discovery and awareness takes place during the Oka crisis in the summer of 1990. Adopted as an infant, Carrie has always felt out of place somehow. Recurring dreams haunt her, warning that someone close to her will be badly hurt. When she finds out that her birth father is Mohawk, living in Kahnawake, Quebec, she makes the journey and finally achieves a sense of home and belonging.

One of the huge holes in children's and young adult literature are stories about Native activism. I had high hopes for this book, especially from a Mohawk writer, but the writing did not strike me as that of someone who is an insider. The dreams throughout the story put it in a space that felt exotic rather than organic, and later in the story, a Native elder is in crisis, and a white doctor (Carrie's mother is a doctor) saves her life. For me, that is the white savior trope. Not recommended.

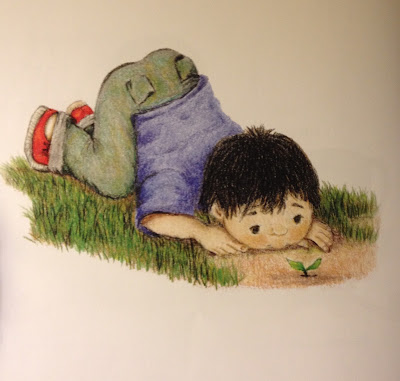

I am happy to recommend The Apple Tree by Sandy Tharpe-Thee and Marlena Campbell Hodson. Published this year by Road Runner Press, the story is about Cherokee boy who plants an apple seed in his backyard.

Here's the cover:

Here's the little boy:

And here's the facing page for the one of the little boy:

I like this anthropomorphized story very much and think it is an excellent book all on its own, and would also be terrific for read-aloud sessions when introducing kids to stories about planting, or patience, or... apples!

When the apple tree sprouts and is a few inches high, the little boy puts a sign by it so that people will see it and not accidentally step on it. That reminds me of my grandmother. She did something similar. To protect a new cedar tree that sprouted near a roadside on the reservation, she make a ring of stones around it so people wouldn't run over it. The apple tree in Tharp-Thee's story grows, as does the boy, and eventually the tree produces apples.

When you read it, make sure you show kids the Cherokee words, and show them the Cherokee Nation's website, too. Help your students know all they can about the Cherokee people. Published in 2015 by The Road Runner Press. The author, Sandy Tharpe-Thee, is a tribal librarian and received the

White House Champion of Change award for her work. She is an enrolled member of the Cherokee Nation.

This is one of those posts people are gonna object to because it is one of the "one liners" -- which means that the book has nothing to do with Native people, but there is a line in it that I am pointing out.

It is "one line" to some, but to Native people or anyone who pays attention to ways that Native people are depicted in children's and young adult literature, those "one lines" add up to a very long list in which we are misrepresented.

Here's the synopsis for Laura Amy Schlitz's The Hired Girl, a 2015 book published by Candlewick (for grades 7 and up):

Fourteen-year-old Joan Skraggs, just like the heroines in her beloved novels, yearns for real life and true love. But what hope is there for adventure, beauty, or art on a hardscrabble farm in Pennsylvania where the work never ends? Over the summer of 1911, Joan pours her heart out into her diary as she seeks a new, better life for herself—because maybe, just maybe, a hired girl cleaning and cooking for six dollars a week can become what a farm girl could only dream of—a woman with a future. Newbery Medalist Laura Amy Schlitz relates Joan’s journey from the muck of the chicken coop to the comforts of a society household in Baltimore (Electricity! Carpet sweepers! Sending out the laundry!), taking readers on an exploration of feminism and housework; religion and literature; love and loyalty; cats, hats, and bunions.

Set in Pennsylvania in 1911,

The Hired Girl has six starred reviews. It is currently listed at Amazon as the #1 bestseller in historical fiction for teens and young adults. Impressive. Hopefully, Schlitz and her editor will revisit the part of the book where a woman tells Joan "You, I think, are not Jewish." Joan responds:

"No, ma'am," I said. I was as taken aback as if she'd asked me if I was an Indian. It seemed to me--I mean, it doesn't now, but it did then--as though Jewish people were like Indians: people from long ago; people in books. I know there are Indians out West, but they're civilized now, and wear ordinary clothes. In the same way, I guess I knew there were still Jews, but I never expected to meet any.

Let's look closely at what Joan said.

The word 'are' in "I know there

are Indians out West..." is in italics. I like that, because I often speak/write of the importance of tense. Most people use past tense when speaking or writing about Native peoples, but we're still here.

But then, Joan thinks "they're civilized now." Does that mean Joan buys into the idea of the primitive Indian who became "civilized" by contact with White people? Do the "ordinary clothes" they wear mean they're civilized?

I'm pretty sure people are going to say that--in asking those two questions--I'm not leaving room for people to do well, or try well, in their writing about Native people.

The fact is, this book is already succeeding and so are ones I've written about before. This post* isn't going to hurt it, but if it does give people (who read AICL) the opportunity to think about words they use in their own writing, that is a plus for all of us.

Native peoples in the U.S. were living in well-ordered societies when Europeans came here. We weren't primitive. Indeed, European heads of state recognized the Native Nations as nations of people. That's why there are treaties. Heads of state, then and now, meet with other heads of state in diplomatic negotiations. Saying "well, Joan didn't know that" is a cop out. She could have known it. Plenty of people did! She's a fictional character. She can know whatever Schlitz wants her to know.

__________

*Replaced "My lone voice" with "This post" in hopes that I'll find other writing that points to this particular passage.

Two years ago I read--and recommended--Kamik: An Inuit Puppy Story, a delightful story about a puppy named Kamik and his owner, a young Inuit boy named Jake. In it, Jake is trying to train Kamik, but--Kamik is a pup--and Jake is frustrated with the pup's antics. Jake's grandfather is in the story, too, and tells him about sled dogs, imparting Inuit knowledge as he does.

Today, I'm happy to recommend another story about Kamik and Jake. The author of Kamik: An Inuit Puppy Story is Donald Uluadluak. This time around, the writer is Matilda Sulurayok. Like Uluadluak, Sulurayok is an Inuit elder.

As the story opens, the first snow of the season has fallen. Jake thinks that, perhaps, he can start training Kamik to be a sled dog, but Kamik just wants to play with the other dogs. Of course, Jake is not liking that at all! Anaanatsiaq (it means grandmother) sees all this going down. She reminisces about her childhood, telling Jake how her dad taught her to train sled dog pups--by playing with them:

In her storytelling of those memories, Anaanatsiaq is teaching Jake. Then she fastens a small bundle on Kamik and suggests Jake take Kamik out, away from the other dogs, for a picnic. They set off walking.

After awhile, Jake opens the picnic bundle. Inside, he finds things to eat, but he also finds a sealskin and a harness.

Playtime training, then, is off and running!

Things get tense, though, when Kamik takes off after a rabbit in the midst of a darkening sky, and Jake realizes he hasn't taught him the command to stop. The rabbit, as you can see, gets away.

Jake is scared, but in the end, Kamik gets him home, where he learns a bit more about sled dogs and their sense of smell.

Through Kamik, Jake, and his grandparents, kids learn about Inuit life, and they learn some Inuit words, too. A strength of both these books is the engaging, yet matter-of-fact, manner in which elders pass knowledge down to kids. Nothing exotic, and nothing romanticized, either.

I highly recommend

Kamik's First Sled, published in 2015 by Inhabit Media.

When I get a book written by a Native person, my heart soars with delight.

In the mail yesterday, I got a copy of Robbie Robertson's Hiawatha and the Peacemaker.

For now, I'm focusing on the words. To start, I flipped to the back pages and read the two-page Author's Note, in which Robertson tells us that he was nine years old when he was told the story of Hiawatha and the Peacemaker. Here's the last paragraph in Robertson's note. When I read it, my delight grew:

Some years later in school, we were studying Henry Wadsworth Longfellow's poem about Hiawatha. I think I was the only one in the class who knew that Longfellow got Hiawatha mixed up with another Indian. I knew his poem was not about the real Hiawatha, whom I had learned about years ago, that day in the longhouse. I didn't say anything. I kept the truth to myself.. till now.

Robertson has done us all a huge service. Teachers and librarians everywhere can ditch all those books with "gitchee gumee" in them. With

Hiawatha and the Peacemaker, young people can--as Robertson said--learn about the real Hiawatha. And, given that Robertson includes the fact that Peacemaker had a speech impediment, I think people within the special needs community will find Robertson's book an invaluable addition to their shelves.

I would love to be at the American Library Association's annual conference next week. At the closing session on Tuesday, June 30th, Robertson and Shannon will have a conversation with Sari Feldman, the incoming president of the association:

Before I sign off on this post (I'll be back with a more in-depth look at the book later), do make sure you get a copy of Sebastian Robertson's biography of his dad:

Rock and Roll Highway: The Robbie Robertson Story! It is terrific.

Earlier this year, I did an analysis of the Native content in Adam Rex's The True Meaning of Smekday. I found the ways that Rex used Native characters and history to be troubling. Some see his parallels to colonization of Natives peoples as having great merit, but the story he tells has a happy ending. The colonizers (aliens called Gorgs from another solar system) do not succeed in their occupation of Earth. They are driven away.

Some people also think Rex cleverly addressed stereotypes in the way that he developed "the Chief" in that story, but I disagree, especially given many things he raised and did not address, like the drunken Indian stereotype.

And some people think that we can overlook all the problems with Native content because there are so few books with biracial protagonists. I disagree with that, too. Why throw one marginalized group under the bus for the sake of another?! That seems twisted and perverse to me.

One of the what-not-to-do cautions in the creation of characters of marginalized populations is "do not kill that character." In The True Meaning of Smekday, Rex killed "the Chief."

In Smek for President, Rex commits another what-not-to-do: use a Native character as a spiritual guide. That character? "The Chief." He died in the first book.

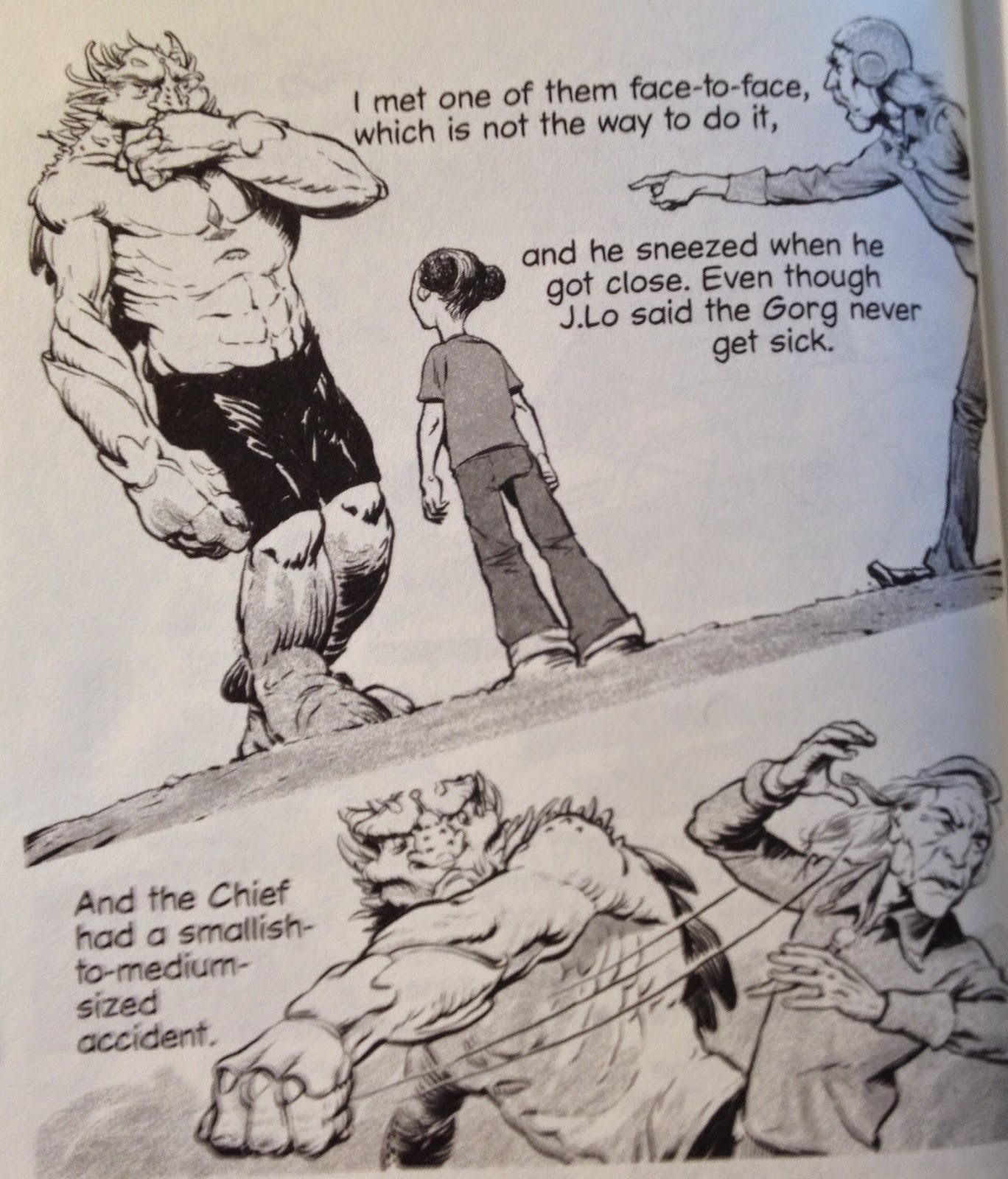

Smek for President opens with a series of cartoon panels that tell us what happened in The True Meaning of Smekday. Amongst the panels are these two. In the first one, we're reminded about "this guy everyone called Chief Shouting Bear."

Back in

The True Meaning of Smekday, we learned that his name is actually Frank, but Tip (the protagonist in both books) just calls him "the Chief." She likes him--there's no doubt about that--but persists in using the dehumanizing "the Chief" throughout the book.

In the first book, Tip had a run-in with a Gorg. That run-in is depicted in the next panel in

Smek for President:

See "the Chief" in the top panel, approaching that Gorg and Tip? He told that Gorg to leave Tip alone. As you see, the Gorg punched "the Chief" (accident is not the right word for what happened!), knocking him out. Tip and J.Lo (he's a Boov) took him to an apartment to get help. That's when Vicky (another character) asks if he'd been drinking.

Towards the end of

The True Meaning of Smekday, "the Chief" dies.

But he appears again and again in

Smek for President...

On page 25, Tip and J.Lo are in their spaceship, flying to New Boovworld and looking out the window at Saturn. Tip thinks back to the time that "the Chief" took her and J.Lo to look at Saturn through a telescope. Here's that part (p. 25-26):

"My people called it Seetin," said the Chief. "Until the white man stole it from us and renamed it."

I turned away from the eyepiece and frowned at the Chief. "Until... what? How can that be true?"

The Chief was smirking. "It isn't. I'm just messing with you."

And now, as we skimmed over the planet's icy rings, I said to J.Lo, "I wish the Chief could have seen this."

He'd died over a year ago, at the age of ninety-four--just a few months after the Boov had left Earth.

That passage is another good example of the author taking one step forward and then two steps backward. By that, I mean that it is good to bring up the idea that Native lands were stolen and renamed, but the "just messing with you" (the humor) kind of nullifies the idea being raised at all. It may even cause readers to wonder what part of "the Chief's" remarks is not true. That his people had a different name for Saturn? That white people didn't really steal Indians?

Tip and J.Lo land their spaceship on New Boovworld. On page 74, Tip is inside an office. She hides by climbing into a chute that drops her in a garbage pit:

Back when the Chief was alive, he and I had all kinds of long talks. Arguments, sometimes. So I don't want you to think I'm schizophrenic or anything, but I occasionally imagine the Chief and I are having one of those talks when I need a little company. And I needed a little company.

"Hey, Stupidlegs," said the Chief.

"Hey, Chief," I answered, smiling. And I opened my eyes. He was to my left, standing lightly on the surface of the trash.

I know people will think it is nice that Tip would imagine an Indian person as the one she'd turn to when she's in need of company, but it is like that far too often!

People love Indian mascots. Indians were so brave, so courageous! Never mind that the mascot itself is a stereotype---we real Native people are told we should feel honored by mascots!

People love Indian spirits, too. Remember "Ghost Hawk" -- the character Susan Cooper created? He started out as Little Hawk but gets killed part way through the story. He stays in the story, however, as a ghost or spirit that teaches the white protagonist all kinds of things.

People love Indians that remind them of days long past, when the land was pristine. Remember

Brother Eagle Sister Sky by Susan Jeffers? A white family laments deforestation and plants trees. Throughout the book, there are ghost-like Indians here and there.

People love scary Indian ghosts, too. All those stories where a house is built on an old Indian burial ground! Those angry Indian spirits do all kinds of bad things. Earlier this year I read a Nancy Drew and the Clue Crew story where Nancy was sure an angry Indian spirit was up to no good. And how about that angry Indian in the Thanksgiving episode of Buffy the Vampire Killer?

My point is that this trope is tiresome. If you see a review that notes this problematic aspect of

Smek for President, do let me know!

Joseph Marshall III is an enrolled member of the Sicangu Lakota (Rosebud Sioux) tribe. Born and raised on the Rosebud Sioux reservation, he is the author of several books about Lakota people. Last year, I read his The Journey of Crazy Horse: A Lakota History. I highly recommend it. In 2011, Marshall's book was selected for the One Book South Dakota project. Over 2400 Native high school students in South Dakota were given a copy of it. How cool is that? (Answer: very cool, indeed!)

Yesterday, I finished his

In the Footsteps of Crazy Horse. First thing I'll say? Get it. Order it now. It won't hit the bookstores till later this year, but pre-order it for your own kids and your library. Like

The Journey of Crazy Horse, it provides insights and stories that you don't get from academic historians.

To my knowledge, there is nothing like it for kids. Some of the reasons I'm keen on it?

First, it is set in the present day on the

Rosebud Sioux reservation. Regular readers of AICL know that I think it is vitally important that kids read books about Native people, set in the present day. Such books provide Native kids with characters that reflect our existence as people of the present day, and they help non-Native kids know that--contrary to what they may think--we weren't "all killed off" by each other, by White people, or by disease, either.

Second, the protagonist, Jimmy McClean, is an eleven-year old Lakota boy with blue eyes and light brown hair. Blue eyes? Light brown hair?! Yes. His dad's dad was White. Those blue eyes and light brown hair mean he gets teased by Lakota kids and White ones, too.

Third, it is a road trip book! I love road trips. Don't you? In this one, his grandfather (his mom's dad) takes him, more or less, in the footsteps of Crazy Horse. Along the way, he learns a lot about Crazy Horse, who--like Jimmy--had light brown hair. When his grandfather is in storytelling mode, giving him information about Crazy Horse, the text is in italics.

Fourth, Jimmy's mom is a Head Start teacher! That is way cool. My little brother and my little sister went to Head Start! When I was in high school, I'd cut school and volunteer at the Head Start whenever I could. But you know what? I can't think of a single book I've read in which one of the characters is a head start teacher, but for goodness sake! Head Start is a big deal! It is reality for millions of people. We should have books with moms or dads who work at Head Start!

Fifth, Jimmy's grandfather imparts a lot of historical information as they drive. At one point, Grandpa Nyles asks him if he's heard of the Oregon Trail. Jimmy says yes, and his grandpa says (p. 29):

"Before it was called the Oregon Trail, it was known by the Lakota and other tribes as Shell River Road. And before that, it was a trail used by animals, like buffalo. It's an old, old trail."

I love that information! It tells readers that Native peoples were here first, and we had names for this and that place.

Sixth, they visit a monument. His grandpa tells him that the Lakota people call it the Battle of the Hundred in the Hands, and that others call it the Fetterman Battle or the Fetterman Massacre. They read the inscription on the monument. See the last line? It reads "There were no survivors." That is not true, his grandpa tells him. Hundreds of Lakota and Northern Cheyenne survived that battle. It is a valuable lesson, for all of us, about perspective, words, who puts them on monuments, why those particular ones are chosen, etc.

Last reason I'll share for now is that Marshall doesn't soft pedal wartime atrocities. Through his grandfather, Jimmy learns about mutilations done by soldiers, and by Lakota people, too. It isn't done in a gratuitous way. It is honest and straightforward, and, his grandfather says "it's a bad thing no matter who does it."

The history learned by reading

In the Footsteps of Crazy Horse and the growth Jimmy experiences as he spends time on that road trip with his grandfather make it invaluable.

In the Footsteps of Crazy Horse, with illustrations by Jim Yellowhawk, is coming out in November from Amulet Books (an imprint of Abrams). Pitched at elementary/middle grade readers, I highly recommend it.

New this year (2015) is Richard Van Camp's graphic novel, The Blue Raven. Illustrated by Steven Keewatin Sanderson, the story is about a stolen bicycle, and, healing. Here's the cover:

The bike, named Blue Raven, belongs to a kid named Benji. He comes out of the library (how cool is that?) and his bike is gone (not cool!). Trevor, the older brother of a kid in his class, sees Benji and offers to help him find the bike.

This isn't just any bike (no bike is, really), but this one? Benji's dad gave it to him when he moved out of their house.

When Benji was born, his dad called him Tatso because his eyes were the same blue color as a baby raven's eyes. Tatso is a

Tlicho word. It means Blue Raven. And--it is the name his dad called the bike, too.

As you might imagine, it is very special to Benji.

We learn all that--and more--as Benji and Trevor drive around on Trevor's four-wheeler, looking for the bike. Trevor is Metis, but wasn't raised with Native traditions in the same way that Benji was. Indeed, there is a moment when Trevor mocks Benji. Confident in what he knows and bolstered by memories of time with members of the community, Benji counters Trevor, who is taken aback and a bit snarky. By the end of this short graphic novel, though, Trevor is with Benji at a gathering where Trevor is invited to dance and the two have agreed to keep looking for the Blue Raven.

Steven Keewatin Sanderson's illustrations are terrific! From anger over his bike being stolen, to the tears Benji sheds in the flashback parts of the story, to the community scenes at the drum dance, they are a perfect match for Van Camp's story. Keep an eye out for his work!

The Blue Raven, published in 2015 by Pearson, is part of its Well Aware series and sold as a package. However, it can be

purchased directly from Richard Van Camp at his site. I highly recommend it.

Anytime someone writes a book--yes, even a work of fiction--that gets basic facts about Native people wrong, it is going to get a 'not recommended' from me.

It doesn't matter, to me, how well-written the story might be and it doesn't matter if the book itself has a protagonist or a cast of characters that are from a marginalized group or groups. Nobody in a marginalized group should be expected to endure the misrepresentation of their own people for the sake of another group. And, all readers who walk away with this misrepresentation as "knowledge" are not well served, either.

So, let's take a look at Hunters of Chaos. The synopsis, from Simon and Schuster:

Four girls at a southwestern boarding school discover they have amazing feline powers and must unite to stop an ancient evil in this riveting adventure.

Ana’s average, suburban life is turned upside down when she’s offered a place at the exclusive boarding school in New Mexico that both of her late parents attended. As she struggles to navigate the wealthy cliques of her new school, mysterious things begin to occur: sudden power failures, terrible storms, and even an earthquake!

Ana soon learns that she and three other girls—with Chinese, Navajo, and Egyptian heritages—harbor connections to priceless objects in the school’s museum, and the museum’s curator, Ms.Benitez, is adamant that the girls understand their ancestry.

It turns out that the school sits on top of a mysterious temple, the ancient meeting place of the dangerous Brotherhood of Chaos. And when one of the priceless museum objects is shattered, the girls find out exactly why their heritage is so important: they have the power to turn into wild cats! Now in their powerful forms of jaguar, tiger, puma, and lion they must work together to fight the chaos spirits unleashed in the ensuing battle…and uncover the terrifying plans of those who would reconvene the Brotherhood of Chaos.

Intriguing? Yes. But... Soon after Ana arrives at the school, there's an earthquake that exposes the mysterious temple. Skipping ahead (for the moment), we learn that the school is (p. 110):

"...yards away from a thriving Native American community, descendants of the Anasazi people..."

For now, I am focusing on the word "Anasazi." For a very long time, that Navajo word was used to describe the people who lived in the cliff houses in New Mexico, Colorado, Arizona, and Utah. The word is no longer in use. Today, "Ancestral Pueblo People" is the phrase people use, because it is the right one to use.

Mesa Verde,

Bandelier,

Chaco Canyon and others are part of the National Park Service. If you click on those links, you'll see they use "ancestral Pueblo/Pueblo People" rather than "Anasazi."

For a long time, literature associated with those sites said that the "Anasazi" people who lived there had vanished. They didn't. Like any people, anywhere in the world, they moved to other locations when conditions changed. In recognition of that fact, the National Park Service and other government sites stopped using Anasazi and started using Ancestral Pueblo People instead. Another good example is the Bureau of Land Management's page,

Who were the Ancestral Pueblo People (Anasazi?).

The massive amounts of literature that used "Anasazi" is probably why Velasquez used it in her book. I wish she had actually looked up the sites I linked to... she'd have avoided the problems in

Hunters of Chaos. In

Hunters of Chaos, Doli is Navajo. Back on page 53 (after they've learned about the temple), Lin (she's the Chinese character) and Doli have an argument. Lin has an expensive purse. Doli makes a sarcastic remark about it, and Lin tells her she's just jealous because she's poor and therefore doesn't belong at the school. Doli says (p. 53):

"I don't belong here?" [...] "You must have been asleep during assembly today. That temple back there means I'm the only one who belongs here."

"Oh, give me a break," Lin said, then sucked her teeth and flicked her hand dismissively. "I was wide awake during Dr. Hottie's speech, and he said the temple was Anasazi, not Navajo."

Doli, completely unfazed, sighed as if she were tired of explaining the obvious. "The Anasazi were an ancient people who lived on this land. In other words, they were my ancestors. Anasazi literally means 'ancient ones' in Navajo."

So. Doli is Navajo. Some people say Anasazi means "ancient ones" and some say it means "enemy people." Whether it meant ancient ones or enemy people, the key thing is that it definitely did not refer to Navajo people. Interestingly, there is a place in the book where we read that Anasazi means ancient pueblo peoples. At that point in the book, the kids have organized an exhibit to show people what the school's museum has--including artifacts from that temple.

Among the people who come to the exhibit is a family from Doli's reservation (the community that thrives a few yards away from the school). A woman speaks to Doli in Navajo. Ana asks her what the woman said. Here's from page 129:

"She said she was glad she could come. They heard about the temple and are excited about it. She didn't think that the ancient Pueblo peoples were active here, so they are very interested in seeing what was found."

See that "ancient Pueblo peoples"? Does the woman think it is her Navajo ancestors?

The confusion between Navajo and Pueblo is a big deal. We're talking about two distinct nations of people.

There are other problems. On page 64, the anthropologist (Dr. Logan) says that Ancient Egyptians, the Ashanti people of West Africa, and the Anasazi worshipped cats. That's the first I ever heard of that said about Pueblo people!

And when Doli starts talking about shape shifting, she doesn't sound like she really grew up there (p. 158):

"Navajo folklore is full of stories about shape-shifters, but I'm not even sure the people on the reservation would believe me."

When the girls first shape shift, Doli says (p. 169):

"I'm glad it happened that way, and not how the Navajo legends say people usually become shape-shifters." [...] "They perform all kinds of evil rites to get the power. I'm talking witchcraft and murder."

When they try to shift later on purpose, they chant Navajo words that Doli taught them. And on page 240, Doli says a few words in Navajo that, she tells us, is a saying amongst her people that means "When you see a rattlesnake poised to strike, strike first." Is that a Navajo saying? I see it attributed to Franklin Delano Roosevelt, but I also find it on a bunch of "Indian proverbs" page, with it being attributed to Navajos. I'll keep digging on that saying. Maybe it IS a Navajo one.

Velasquez is working on a sequel to this book.

I hope this confusion between two nations does not continue. Published in 2015 by Simon and Schuster, I cannot recommend

Hunters of Chaos.

Last year I read Daniel Jose Older's excellent essay in Slate. Titled "Diversity is Not Enough: Race, Power, Publishing," it was shared widely in my social media networks. I started following him on Twitter, and learned that he had a young adult book in the works. By then I'd already read Salsa Nocturna and loved it. His is the kind of writing that stays in your head and heart.

I've now read his young adult novel, Shadowshaper, and am writing about it here. Older is not Native, and his book is not one that would be categorized as a book about Native peoples. There are, however, significant overlaps in Indigenous peoples. There are parallels in our histories and our current day politics.

Here's the cover:

The girl on that cover is Sierra, the protagonist in Older's riveting story. She paints murals. Here's the synopsis:

Sierra Santiago planned an easy summer of making art and hanging out with her friends. But then a corpse crashes the first party of the season. Her stroke-ridden grandfather starts apologizing over and over. And when the murals in her neighborhood begin to weep real tears... Well, something more sinister than the usual Brooklyn ruckus is going on.

With the help of a fellow artist named Robbie, Sierra discovers shadowshaping, a thrilling magic that infuses ancestral spirits into paintings, music, and stories. But someone is killing the shadowshapers one by one -- and the killer believes Sierra is hiding their greatest secret. Now she must unravel her family's past, take down the killer in the present, and save the future of shadowshaping for generations to come.

That synopsis uses the word "magic." Older uses "spiritual magic" at his

site. I understand the need to use that word (magic) but am also apprehensive about it being used in the context of Indigenous peoples and people of color. Our ways are labeled with words like superstitious or mystical--words that aren't generally used to describe, say, miracles done by those who are canonized as saints. It is the same thing, right? Whether Catholics or Latinas or Native peoples, beliefs deserve the same respect and reverence.

For anyone with beliefs in powers greater than themselves, there are things that happen that are just the norm. They're not mystical or otherworldly. They are just there, part of the fabric of life.

Anyway--that's what I feel as I read

Shadowshaper. The shadowshaping? It blew me away. I love those parts of the book. We could call them magical, but for me, they are that fabric of life that is the norm for Sierra's family and community. When she starts to learn about it, she doesn't freak out. She tries to figure it out.

She does some research that takes her to an archive, which eventually leads her to a guy named Jonathan Wick who wants that shadowshaping power for his own ends.

That archive, that guy, that taking? It points to one of the overlaps I had in mind as I read

Shadowshaper. Native peoples in the U.S. have been dealing with this sort of thing for a long time. Someone is curious about us and starts to pry into our ways, seeking to know things not meant for him, things that he does not understand but is so intoxicated by, that he has to have it for himself. It happened in the 1800s; it happens today.

But let's come back to Sierra. She's Puerto Rican. When she starts her research in the library at Columbia University, she meets a woman named Nydia who wants to start a people's library in Harlem that will be filled with people's stories. Pretty cool, don't you think? Nydia works there, learning all she can to start that people's library. Amongst the things she has is a folder on Wick. She tells Sierra (p. 50):

He was a big anthro dude, specifically the spiritual systems of different cultures, yeah? But people said he got too involved, didn't know how to draw a line between himself and his -- she crooked two fingers in the air and rolled her eyes -- "subjects. But if you ask me, that whole subject-anthropologist dividing line is pretty messed up anyway."

Sierra asks her to elaborate. Nydia says it would take hours to really explain it but in short (p. 51),

"Who gets to study and who gets studied, and why? Who makes the decisions, you know?"

I can't think of a work of fiction in which I read those questions--straight up--in the way that Older gives them to us. Those are the big questions in and out of universities. We ask those questions in children's and young adult literature, and Native Nations have been dealing with them for a very, very long time. I love seeing these questions in Older's book and wonder what teen readers will take away from them? What will teachers do with them? Those questions throw doors wide open. They invite readers to begin that crucial journey of looking critically at power.

Older doesn't shy away from other power dynamics elsewhere in the book. Sierra's brother, Juan, knew about shadowshaping before she did because their abuelo told him about it. When Sierra asks Juan why she wasn't told, too, he says (p. 110):

"I dunno." Juan shrugged. "You know Abuelo was all into his old-school machismo crap."

Power dynamics across generations and gender are tough to deal with, but Older puts it out there for his readers to wrangle with. I like that, and the way he handles Sierra's aunt, Rosa, who doesn't want Sierra to date Robbie because his skin is darker than hers. Sierra says (p. 151):

"I don't wanna hear what you're saying. I don't care about your stupid neighborhood gossip or your damn opinions about everyone around you and how dark they are or how kinky their hair is. You ever look in the mirror, Tia?"

"You ever look at those old family albums Mom keeps around?" Sierra went on. "We ain't white. And you shaming everyone and looking down your nose because you can't even look in the mirror isn't gonna change that. And neither is me marrying someone paler than me. And I'm glad. I love my hair. I love my skin."

I love Sierra's passion, her voice, her love of self, and I think that part of

Shadowshaper is going to resonate a lot with teens who are dealing with family members who carry similar attitudes.

Now, I'll point to the Native content of

Shadowshaper.

As I noted earlier, Sierra is Puerto Rican. That island was home to Indigenous people long before Columbus went there, all those hundreds of years ago. At one point in the story, Sierra notices the tattoo on Robbie's arm. He asks her if she wants to see the rest of it. She does, so he pulls his shirt off (p. 125):

It was miraculous work. A sullen-faced man with a bald head and tattoos stood on a mountaintop that curved around Robbie's lower back toward his belly. The man was ripped, and various axes and cudgels dangled off his many belts and sashes.

"Why they always gotta draw Indians lookin' so serious? Don't they smile?"

Did you notice the tense of her last question? She asks, in the present, not the past. There's more (p. 126):

"That's a Taino, Sierra."

"What? But you're Haitian. I thought Tainos were my peeps."

"Nah, Haiti had 'em too. Has 'em. You know..."

"I didn't know."

That exchange is priceless. In the matter-of-fact conversation between Robbie and Sierra, Older guides readers from the broad (Indian) to the specific (Taino) and goes on to give even more information (that Taino's are in Haiti, too).

But there's more (p. 126)!

Across from the Taino, a Zulu warrior-looking guy stood at attention, surrounded by the lights of Brooklyn. He held a massive shield in one hand and a spear in the other. He looked positively ready to kill a man. "I see you got the angry African in there," Sierra said.

"I don't know what tribe my people came from, so it came out kinda generic."

It is good to see a character acknowledge lack of knowing! It invites readers to think about all that we do not know about our ancestry, and what we think we know, too... How we know it, what we do with what we know...

What I've focused on here are the bits that wrap around and through Older's wonderful story. Bits that are the warm, rich, dark, brilliant fabric of life. Mainstream review journals are giving

Shadowshaper starred reviews for the story he gives us. My starred review is for those bits. They matter and they speak directly to people who don't often see our lives reflected in the books we read. I highly recommend

Shadowshaper. Published in 2015 by Arthur A. Levine Books, it is exceptional in a great many ways.

Willa Strayhorn's The Way We Bared Our Souls opens with a deeply problematic scene. The characters in the story are inside a "ceremonial kiva" (p. 1). Chronologically, this scene is from the last part of the story Strayhorn tells.

Told from the viewpoint of Consuelo (called Lo for short), an "Anglo, not Hispanic" (p. 11) character, she is in this "ceremonial kiva" with three others. Missing is Kaya, "the girl who felt no pain" (p. 1).

Kaya, we learn later, is "Pueblo on her mom's side and Navajo on her dad's" (p. 66). Of course, she's got high cheekbones. She's not in that opening scene, because by the end of the story she's dead.

These teens go to Santa Fe High School, in Santa Fe, New Mexico. I'm from Nambe Pueblo, about 30 miles north of Santa Fe. It is where we went, as teens, to see a movie, eat out, etc. There's a lot of things in the novel that don't jib with the Santa Fe that I know, like the part where Consuelo sees the school mascot at a party (Santa Fe High's mascot is a demon, not a buffalo) and the part where Consuelo and Ellen are at the train depot and Ellen talks about wanting to hop a train to parts unknown (there's been no train service like that in Santa Fe for a very, very long time; the only train in recent times is the Railrunner, which is a commuter train that runs from Santa Fe to Albuquerque). There's other things, too, that yank me out of the story, but I want to focus on what Strayhorn does with Native culture.

They're in this kiva because of Consuelo. A week prior to that opening scene, she'd been to the doctor. Her likely diagnosis was multiple sclerosis. Understandably upset, she's gone for a drive. A coyote runs out in front of her car. She pulls over and is approached by a guy with "silky dark hair" named Jay. There's some chitchat and then (p. 28):

"What happened to your blood, dear?" he said.

And

"You're unwell, he said. You're... afflicted. Is it your blood, sweetheart?"

She tells him it is her brain (I cringed when I read "dear" and "sweetheart"). He can sense her pain and suffering and tells her that her (p. 29):

"...essential well-being is much deeper than the burden your body carries. You do not have to be tyrannized by your disease."

See that word, "burden"? Jay is going to suggest that Consuelo invite four friends to go through a healing ritual that will heal her energy and release her from her burden. The "powerful medicine" in this ritual "can eliminate your pain and disease and teach you to accept everything fate throws your way. With joy" (p. 33).

Of course, she agrees, and invites four kids from school to do it with her.