new posts in all blogs

Viewing: Blog Posts Tagged with: new_voice_2015, Most Recent at Top [Help]

Results 1 - 21 of 21

How to use this Page

You are viewing the most recent posts tagged with the words: new_voice_2015 in the JacketFlap blog reader. What is a tag? Think of a tag as a keyword or category label. Tags can both help you find posts on JacketFlap.com as well as provide an easy way for you to "remember" and classify posts for later recall. Try adding a tag yourself by clicking "Add a tag" below a post's header. Scroll down through the list of Recent Posts in the left column and click on a post title that sounds interesting. You can view all posts from a specific blog by clicking the Blog name in the right column, or you can click a 'More Posts from this Blog' link in any individual post.

By

Susan Thogerson Maasfor

Cynthia Leitich Smith's

CynsationsWhy do we write middle grade and young adult books? Perhaps we love to play with words. Or we admire the honesty and realness of kids—and never quite grew up ourselves.

These reasons also apply to those of religious faith, but we have an added motive—to inspire children, deepen their faith, or help them live a better life. These ideas can be part of both religious and mainstream market books.

Writing faith themes in children’s literature can be fulfilling and fun. My first middle grade novel—

Picture Imperfect, published by Ashberry Lane—came out in 2015.

Writing this book (and prior failed attempts) taught me a few things about writing middle grade fiction from a faith perspective.

1. Choose an appropriate theme. People of faith believe life has meaning and God speaks through our circumstances. Naturally, we want to express the truth, as we see it, through our stories. But keep it kid-appropriate. (Forgiveness and loving others are great, fire and brimstone not so much.)

As a child, I loved reading books that inspired me and gave me hope. Now I love writing those books. In Picture Imperfect, my young protagonist, JJ, faces many challenges, including an annoying live-in aunt, a runaway cat, and her great-grandmother’s death. But she grows and finds God through the challenges.

2. Put story first.Concepts of faith and moral values should emerge organically from the story. Nobody—least of all a child—wants to have a message hammered into them. And forcing a theme onto a story rarely works. I’ve tried it—that book never sold.

Picture Imperfect started out being about a girl discovering faith through her beloved great-grandmother. As I wrote, that element remained, but the focus shifted to JJ finding her place in the family.

|

| Susan & middle grade author Angela Ruth Strong, 2015 Oregon Christian Writers’ summer coaching conference |

3. Don’t preach. Show, don’t tell is the Golden Rule of writing, and it applies equally to faith-based writing. Let the characters’ experiences and interactions demonstrate the underlying concept. While hints of it may appear in conversation, keep it light. Children would rather discover meaning for themselves than have some wise character explain it.

Picture Imperfect does have a “mentor” character with the occasional pithy saying, but the character's life, more than her words, helps JJ discover the importance of faith.

|

| Susan's book launch with critique partner Sandy Zaugg |

4. Use symbolism and metaphor. The Chronicles of Narnia by C.S. Lewis (1949-1954) is a clearly Christian series, yet never mentions God. In Picture Imperfect, the stained-glass windows of a small church illustrate the protagonist’s longing for God. These tools must be used carefully, of course. An allegory heavy with symbolism may turn off readers. But a gentle touch can add depth.

|

| Not Back to School Day (Portland)* |

5. Portray all faiths positively. Faith themes can work in both the religious and general markets, although emphasis will differ. Even nonreligious books can add diversity by including children of different faiths, whose religion is a normal part of their lives.

A final thoughtBelievers, there’s no need to force spiritual themes into your stories. Your faith will naturally come out in whatever you write.

Cynsational Notes

Susan Thogerson Maas grew up on five green Oregon acres, coming to love the plants, birds, and wild critters of the woods—who often find their way into her writing. She has written part-time for 30 years, selling devotionals, homeschooling and personal experience articles, Sunday school curriculum, and children’s stories.

Picture Imperfect is her first published middle grade novel. She is currently working on another middle grade novel, along with a nature-based homeschool unit study.

Susan chose to publish with

Ashberry Lane, a small Christian publisher, due to the supportive, caring environment it offers. The mother-daughter publishing team works closely with the authors, and the authors work together to promote each other’s writing. In today’s publishing world, most authors end up doing much of their own marketing, but Ashberry Lane’s family atmosphere provides both physical help and spiritual encouragement.

*with Christian Tarabochia, Sherrie Ashcraft.

|

| Ashberry Lane family (Aug. 2014): from left: Sherrie Ashcraft (publisher), authors Sam Hall, Angela & Jim Strong, Bonnie Leon, Susan Maas, Camille Eide; cover designer-board member Nicole Miller & editor Christina Tarabochia |

By:

Cynthia Leitich Smith,

on 2/16/2016

Blog:

cynsations

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

fantasy,

Texas author,

Austin SCBWI,

giveaway,

Jill Santopolo,

Debbie Gonzales,

new_voice_2015,

Paige Britt,

Marietta B. Zacker,

Add a tag

By

Cynthia Leitich Smithfor

CynsationsPaige Brittis the first-time author of

The Lost Track of Time, illustrated by Lee White (Scholastic, 2015). From the promotional copy:

A magical fantasy, an allegorical cautionary tale, a feast of language, a celebration of creativity--this dazzling debut novel is poised to become a story for the ages.

Penelope is running out of time.

She dreams of being a writer, but how can she pursue her passion when her mother schedules every minute of her life? And how will she ever prove that writing is worthwhile if her mother keeps telling her to "get busy " and "be more productive"?

Then one day, Penelope discovers a hole in her schedule--an entire day completely unplanned --and she mysteriously falls into it. What follows is a mesmerizing journey through the Realm of Possibility where Penelope sets out to find and free the Great Moodler, the one person who may have the answers she seeks. Along the way, she must face an army of Clockworkers, battle the evil Chronos, take a daring Flight of Fancy, and save herself from the grip of time.

Brimming with clever language and masterful wordplay, The Lost Track of Time is a high-stakes adventure that will take you to a place where nothing is impossible and every minute doesn't count--people do. Was there one writing workshop or conference that led to an "ah-ha!" moment in your craft? What happened, and how did it help you? |

| Jill Santopolo |

I absolutely do have a most memorable workshop! It was actually one you gave in 2008 with

Jill Santopolo, author and editor at Philomel Books. Even though it was over seven years ago, I’ve never forgotten it.

The workshop was organized by the

Austin SCBWI and hosted by

Debbie Gonzales, who was regional advisor at the time.

To register, you had to submit three pages of a work-in-progress. A few weeks before the event, everyone received a packet with copies of all the three-page submissions. Then during the workshop, you and Jill went through each submission and discussed it with the entire group.

You were both kind and encouraging, but also very honest. Jill told us that editors were looking for a reason to say “no” when they read a manuscript. Together you discussed each submission and pointed out the potential “no’s.” Meandering openings, overly long backstory, and hazy plot lines were the most common mistakes.

Even though what you had to say was tough, it was clear you were invested in everyone’s success. You wanted to turn those no’s into yes’s.

Here’s the funny thing. I didn’t even submit my three pages. I registered too late to be a part of the critique, but I went to the workshop anyway. And I’m so glad I did! After the workshop I went home, re-read my three pages, and guess what? They were meandering, “explain-y,” and vague. But because of your input, I could see it. And if I could see it, I could fix it.

|

| Cynthia Leitich Smith & Debbie Gonzales |

The Lost Track of Time opens with an alarm clock going off, “Beep. Beep. Beep. Beep.” It’s 6 a.m. and even though it’s summer vacation, the main character, Penelope, has to get up and get busy. Right from the start, you know that the central conflict in the story is time.

I did that because of what I learned from you and Jill.

After I fixed my first chapter, I submitted it to two conferences and had sit-down conversations with agents at both. The first agent asked for thirty more pages and the second one,

Marietta B. Zacker, signed me. There is absolutely no way that would have happened if I hadn’t gone to that workshop. I’ve always wanted to tell you and Jill how much you helped me!

As a fantasy writer, going in, did you have a sense of how events/themes in your novel might parallel or speak to events/issues in our real world? Or did this evolve over the course of many drafts?From the beginning, I knew The Lost Track of Time was intimately connected to real-world issues. When I started writing it, I was working for an internet startup. I was constantly on the clock, from morning until night and over the weekends, trying to make the company a success. Everyone was fighting for more time—but no matter what we did, there was never enough. And what time we did have, had to be spent

Constantly! Achieving! Results! Not surprisingly, The Lost Track of Time is about a girl who likes to do nothing. Doing nothing seemed to me like a radical and counter-cultural act. I’m not talking about the nothing where you lie around flipping through TV channels because you’re too exhausted to engage in life.

I’m talking about moodling.

I learned about moodling from

Brenda Ueland in her book,

If You Want to Write. She writes:

“The imagination needs moodling–long, inefficient, happy idling, dawdling and puttering.”

I agree. When you moodle, you’re quiet, still, and (horrors!) unproductive. You let your mind wander until it becomes calm and curious and open. It’s a space of quiet contemplation and intense creativity.

During this busy time in my life, I had no time for quiet contemplation. But when I discovered Brenda Ueland’s words, I suddenly felt I had permission to sit, stare out the window, and moodle. Not only did I have permission, it was imperative that I do so if I wanted to let my own ideas and stories to “develop and gently shine.”

Ueland’s encouragement that everyone moodle touched me so deeply that she inspired a character in my book. She’s the Great Moodler and Penelope fights the tyranny of Chronos and his Clockworkers to save her from banishment in the Realm of Possibility.

As Penelope faces each trial with both imagination and courage, she moves from being an insecure, apologetic daydreamer to a great moodler in her own right.

Research shows a marked decline in U.S. children’s creativity, due to a lack of unstructured free time to play and, I would say, to moodle.

This is terrible news! Not just because creativity is wonderful and life-giving, but because it’s the best predictor we have of a child’s future success, not just in the realms of art and literature, but in the world of business, science, and technology, too.

I’m not sure if you can teach creativity, but I do think you can encourage it. And that’s what I wanted to do in The Lost Track of Time.

I wanted to hold up moodlers as heroes.

Not because they can wield a sword, but because they dare, like Penelope, to enter the Realm of Possibility—to live in the present, to be creative and contemplative, and to believe anything is possible.

|

| Paige's desk |

Cynsational GiveawayEnter to win one of two signed copies of

The Lost Track of Time by

Paige Britt, illustrated by Lee White (Scholastic, 2015). Author sponsored. Eligible territory: U.S.

a Rafflecopter giveaway

By

Cynthia Leitich Smithfor

CynsationsChristine Hayes is the first-time author of

Mothman's Curse, illustrated by

James K. Hindle (Roaring Brook, 2015). From the promotional copy:

Josie may live in the most haunted town in America, but the only strange thing she ever sees is the parade of oddball customers that comes through her family’s auction house each week. But when she and her brothers discover a Polaroid camera that prints pictures of the ghost of local recluse John Goodrich, they are drawn into a mystery dating back over a hundred years. A desperate spirit, cursed jewelry, natural disasters, and the horrible specter of Mothman all weave in and out of the puzzle that Josie must solve to break the curse and save her own life.How do you psyche yourself up to write, to keep writing, and to do the revision necessary to bring your manuscript to a competitive level? What, for you, are the special challenges in achieving this goal? What techniques have worked best and why?I so envy writers who are able to follow a set routine. That would be the ideal. I’d love to be more productive, more disciplined! But the truth is, while I try to spend time every day writing or revising, I often end up staring at the computer screen, reworking the same passage over and over, or finding jobs to do around the house that could easily wait.

If I go several days without any forward writing progress—and to me that can include blogging or marketing efforts—then I become anxious and unsettled.

|

| Christine's work space |

I find I have to set small, measurable goals and break big projects up into bite-size pieces to fool myself into not feeling overwhelmed. I’ll mark a deadline on the calendar, then work backward to determine how much I have to get done each day. Even imaginary deadlines can be valuable motivators!

Then I try to follow through in unconventional ways, mixing up my routine from day to day. I’ll work a few days at home at the kitchen table, another day sitting in the car at the park, another at a local café. On a few occasions when I was facing critical deadlines, I checked into a hotel to sharpen my focus and cut down on distractions.

For first drafts, I get the most done with a notebook and pen, writing things out by hand. Later, as I type what I’ve written, I’m able to self-edit, adding or cutting as needed. It’s an effective way to shape the story early on.

For the next round of revisions I often print out a chapter at a time and use a red pen to mark it up. Sometimes there are only a few usable sentences left per page once the ink dries. It’s tough to watch the word count shrink, but satisfying to see those few sentences that are able to withstand a more intense level of scrutiny.

As far as making a manuscript competitive—polished, professional—I think it’s a dichotomy. You can’t compare your work to others, because you will always feel like you fall short.

|

| Christine's pottery collection |

I love the quote, “Comparison is the thief of joy.” I see this with my kids all the time. If I were to give them each a cupcake, they’d be happy for a minute or two, but they would inevitably notice that a sibling has more frosting or less frosting or a better color of frosting or whatever. As adults, we never quite grow out of this.

At the same time, you should be reading every day—books both in and out of your genre, news articles, magazines, something. Not to compare, but to fill your mind with words of all kinds, drinking in what’s beautifully done, learning lessons from work that’s perhaps less polished, clichéd, poorly paced, etc.

Set a high standard for yourself. Maybe six months ago you wrote something and said, “This is my best work.” But then you write something new and when you revisit your earlier work you realize that you’ve grown as a writer. It’s a beautiful and amazing process.

I struggle with procrastination and self-doubt. I also tend to overthink, to tinker with passages too much, but at some point I have to stop fussing and just let go. The gauge for me is feeling like it’s the best I can produce in that moment in time, until my agent or editor gently points out the many ways a piece can be improved!

As a paranormal writer, what first attracted you to that literary tradition? Have you been a long-time paranormal reader? Did a particular book or books inspire you?I’ve been fascinated with the paranormal since grade school. As a young teen, I would check out stacks of ghost story anthologies from the library. I had mostly given up on kids’ novels at that point. I found it so disappointing when I would choose a book that seemed like it was about a ghostly mystery, only to discover that the “ghost” was a fake, dreamed up by the bad guy to hide some evil plot. I craved books that celebrated the unexplained.

One book I do remember falling in love with was

A Wrinkle in Time by

Madeleine L’Engle (FSG, 1963). Though not precisely a paranormal story, it was full of wonder and possibility.

I had the same teacher, Mrs. Tapscott, for both fourth and fifth grades. She read to us every day, and one of the books she read was A Wrinkle in Time. She had this sweet southern voice, and she had no patience for kids who thought they were too cool to listen during reading time.

She also read

The Hobbit by

J.R.R. Tolkien (George Allen & Unwin, 1937),

The Cay by

Theodore Taylor (Avon, 1969), and My Side of the Mountain by

Jean Craighead George (Dutton, 1959). She was an incredible lady.

I also remember seeing

commercials for a series of Time Life books called Mysteries of the Unknown. I wanted so badly to own every volume. A few years ago I found one at a garage sale for a dollar. Of course I snapped it right up! Isn’t it funny, the things we carry with us from childhood?

Outside of books, one specific influence that stands out in my memory is the show

“In Search Of,” hosted by

Leonard Nimoy in the late 70s/early 80s. Each week they would explore an aspect of the unexplained: the Bermuda Triangle, aliens, Bigfoot, the Loch Ness Monster. I ate it up.

Then, of course, were the slumber parties where we watched movies like

"Psycho" and

"The Lady in White." It was delicious, that shared feeling of fear: hiding behind our pillows, imagining footsteps outside the window—because in fact we were perfectly safe. We were seeing new facets of the world, exploring what it meant to be brave.

I think spooky books are appealing because they offer adventure, escape—a vicarious experience in a parallel world. They allow kids to view fear through a lens that hopefully makes their real-world problems a little less scary, a little easier to face.

These days I love

"M Night Shyamalan" movies and the show

"Supernatural." I even watch the occasional episode of

"Ghost Hunters." My husband teases me about my “creepy side.” But I’ve never enjoyed slasher movies or anything gory, especially zombies. They give me nightmares!

It’s probably why I write middle grade. I love a good scare, but nothing graphic. I think what you don’t show can be even scarier than spelling out the grisly details. The movie

"The Village" comes to mind here. It wasn’t well-received by critics, but it created an almost tangible atmosphere on the screen. It had gorgeous, enticing cinematography, a washed-out color palette with hints of red (“the bad color”), and an epic soundtrack. I thought it was beautifully done.

I’m also fascinated by old things and abandoned places. Every broken-down barn or rusting piece of junk tells a story. You can almost feel the history there as you imagine the ghosts that might be lingering. It’s my go-to source for inspiration.

By

Cynthia Leitich Smithfor

CynsationsDanica Davidson, welcome back to Cynsations and congratulations on the release of Attack on the Overworld(Skyhorse, 2015)! What inspired you to choose the particular point of view--first, second, third, omniscient (or some alternating combination) featured in your novel? Usually I don't decide what point-of-view I want to use, because the story comes to me with the point of view already intact, if that makes sense.

My new book, Attack on the Overworld, is a sequel to

Escape from the Overworld (

author interview), and both times the story "came to me" in first person.

I'd just sold a manga book to Skyhorse Publishing and was pitching a YA series with my agent when Skyhorse asked if I could come up with a pitch for a Minecraft book.

I came up with a proposal for a fictional middle grade novel pretty quickly, because Stevie, the main character of the books, came to me pretty quickly. I didn't know his name was Stevie yet, but he was a kid living in the Minecraft world and I could picture him and I could start hearing his voice running in my head, telling his story.

I was a little hesitant at first to write it in first person, because when I took a look at the other Minecraft books out there, they all seemed to be in third person. I was bucking the trend. I tried thinking about Stevie's adventures in third person, to see if I could shift, and then the words wouldn't come. Stevie had made it pretty clear he wanted me to tell this from his point of

view.

So how was I going to write as if I were an eleven-year-old boy, even though I wasn't eleven or a boy?

Well, that's the fun of it. Like actors taking on different roles, I often like to write from the point of view of people I'm not. To help me "get in character," I read my writings from when I was eleven and other books aimed for the same age group.

With the first book, Escape from the Overworld, Stevie introduced himself pretty quickly, but I was still getting to know him. For the sequel, he was like a friend and it was easier to bring out his voice.

As a fantasy writer, going in, did you have a sense of how events/themes in your novel might parallel or speak to events/issues in our real world? Or did this evolve over the course of many drafts?I think fantasy can be a great way to creatively look at real issues in a new light. In Escape from the Overworld, the characters deal with feelings of insecurity and bullying from schoolmates. In the sequel, Attack on the Overworld, I decided I wanted to take on cyberbullying.

The setup is that Maison, an eleven-year-old girl who lives in our world, accidentally creates a portal to the Minecraft world with her computer. This is how she meets Stevie and he gets to visit our world.

But in the sequel, cyberbullies hack into Maison's computer and get to the portal. They let themselves into the Minecraft world, turn it into eternal night (this is when the monsters come out during the game) and unleash zombies on the village. Soon the village is overrun and Stevie and Maison are the only ones in the area who haven't been turned into zombies.

A realistic take on cyberbullying? Well, no. But through this creative way of talking about it, I can show how devastating cyberbullying can feel. It also lets the different characters (including the cyberbullies) talk about how cyberbullying affects them. The cyberbullies, one in particular, talk about why they first started bullying people online, and once they can understand the driving force, they can take steps to change. The book also shows how kids who are cyberbullied can stand up for themselves and go to adults for help.

A lot of the articles I've read on cyberbullying have repeated the same information and don't really have any emotion to them, because they're reporting. By giving characters these issues, I think it makes it more emotional and I hope it gets people more able to talk about cyberbullying.

Because I'm a public figure working online, I've been cyberbullied. Then I've read articles about people who have been so badly cyberbullied and so hurt by it that it's messed up their lives. This is not something we should be ignoring or dismissing.

Coincidentally, the YA series I'm shopping around is also a fantasy that takes on real life issues that teens face . . . hopefully this is something I can soon be sharing with readers as well!

By

Cynthia Leitich Smithfor

CynsationsLaurie Wallmark is the first-author of

Ada Byron Lovelace and the Thinking Machine (Creston, 2015). From the promotional copy:

Ada Lovelace, the daughter of the famous romantic poet, Lord Byron, develops her creativity through science and math. When she meets Charles Babbage, the inventor of the first mechanical computer, Ada understands the machine better than anyone else and writes the world's first computer program in order to demonstrate its capabilities. Could you describe both your pre-and-post contract revision process? What did you learn along the way? How did you feel at each stage? What advice do you have for other writers on the subject of revision?Like everyone else, I did many, many revisions before I thought the manuscript ready to submit. In June 2013, I had a manuscript critique at the New Jersey

SCBWI conference with Ginger Harris of the

Liza Royce Agency. She and her partner, Liza Fleissig, both thought the manuscript showed promise and would be of interest to Marissa Moss of

Creston Books.

|

| 1,000 lucy paper cranes |

I did a revision for them, and then they sent it to Creston Books. Marissa like the story enough to send me a revise and resubmit letter—four times!

It was at this point that I began to lose hope. Would she ever think Ada’s story good enough to acquire?

Apparently she would, since at that point, Marissa offered a contract. But the revisions didn’t stop there. I did about ten more before she thought the text was ready to pass on to the illustrator,

April Chu.

Of course, not all ten were major revisions, but every word had to be just right, since a picture book has so few of them.

The biggest thing I learned along the way is that no matter how good you think your manuscript is, it can always be made better. The second was a good editor is invaluable.

My biggest advice to other writers is to be open to changes.

No, you don’t have to take every suggestion offered, but you need to seriously consider each one. Remember, this takes time.

As a nonfiction writer, what first inspired you to take on your topic? What about it fascinated you? Why did you want to offer more information about it to young readers?I love STEM (science, technology, engineering, math) and wanted to share this love with young readers—not just with geeks like me, but with all children, no matter how STEM-phobic they may be.

Many children say they hate STEM or worse, they’re bad at it. As a society, we need to turn this perception around. Children are growing up in a high-tech world and need to feel comfortable in it.

But the question for me was, how could I make STEM interesting and fun for children through my writing while avoiding the dreaded “issues” book?

I realized a picture book biography is an ideal medium to introduce STEM concepts and facts to young readers. Instead of only offering STEM content through dry, boring textbooks, teachers could use picture book biographies to immerse children in the subject matter. They could enjoy a story while learning STEM along the way. I think of this as guerilla teaching.

Once I decided I’d write a biography, I had to choose a person to profile. I’m drawn to writing about strong, under-appreciated women in STEM. I feel it’s important for all children, not just girls, to realize the many extraordinary contributions of women in STEM. Ada was the world’s first computer programmer, yet few people have heard of her. And she did this in the 1800s!

In addition to showcasing a woman in STEM, I wanted to portray a person who had faced challenges in her life. Ada suffered from an assortment of health problems. As a child, a case of measles left her blind and paralyzed. Her sight soon returned, but Ada was bedridden for three years.

|

| Laurie in third grade. |

Many children have challenges of their own to overcome. Seeing how Ada succeeded in spite of her lifelong health problems might help them realize they can too.

When people hear I’ve written a picture book about Ada Byron Lovelace, often their first question is “Who’s that?” It makes me sad to realize most people have never heard of such an important person in STEM. Is this because she was a woman?

Because of Ada’s accomplishments and her overcoming of obstacles, I knew I had to write about her in my first picture book biography.

Additionally, in a previous career, I was a programmer, and I now teach computer science. How could I not write about Ada Byron Lovelace, the world’s first computer programmer? Without a doubt, I had to share her story.

|

| Wall of gear shapes from book launch! |

Cynsational GiveawayEnter to win one of two signed copies of

Ada Byron Lovelace and the Thinking Machine by

Laurie Wallmark (Creston, 2015). Author sponsored. Eligibility: U.S. only.

a Rafflecopter giveaway

By

Cynthia Leitich Smithfor

CynsationsK.C. Maguire is the first-time author of

Inside the Palisade (Lodestone, 2015). From the promotional copy:

Omega has grown up surrounded by women – literally.

Inside the palisade, women fall in love, marry and raise daughters, relying on an artificial insemination process known as the Procedure. But something goes horribly wrong.

One day, Omega comes face to face with a mythical monster – a man – within the society’s walls. Men had been eradicated long ago to protect women from the threat of violence. But this boy is not what Omega has been led to believe. And he needs her help.

She soon finds herself embroiled in a manhunt headed by a vigilante Protector, Commander Theta.

When she falls into Theta’s clutches, Omega realizes that there’s more to the banishment of men, and to her own past, than she’s ever known. Ultimately, she is forced to make a choice between betraying the lost boy and betraying her society, a decision complicated by the realization that she has more in common with him than she cares to admit, and the fact that she is developing feelings for him.Could you tell us about your writing community – your critique group or partner or other sources of emotional and/or professional support.Because I’ve moved around a lot for my day job in recent years, it’s been a challenge to find a writing community that works for me. Lately, one of the most important sources of support and inspiration has been the amazing

VCFA community. I’ve managed to find a network of friends, colleagues, and beta readers who are always there for questions, comments, reads, and general support.

I’m predominantly a YA writer, so I’ve also found writing groups through the regional branches of

SCBWI in cities where I’ve lived. I have two amazing groups of writing friends in Houston, TX, one of which is an SCBWI critique group that meets weekly and provides as much friendship and support as thoughtful critiquing. It’s a wonderful mixture of picture book, middle grade, and young adult writers who experiment with different genres and are always willing to read something new. The other is a marketing support group where we experiment with different approaches to cross-promotions of our work whether traditionally, independently, or self-published.

|

| HarperTeen, 2016 |

As I’m currently living in Ohio, I’ve also been lucky enough to find some wonderful writing friends in the Midwest. North East Ohio is a great place for YA writers many of whom are extremely generous with their time and thoughts. Particular shout-outs here to

Cinda Williams Chima and

Rebecca Barnhouse!

It’s always a blessing to find new people who “get” your work and your process, and it’s wonderful when you can develop a shorthand way of critiquing with people who are familiar enough with your writing tics to be able to go for the jugular (in a good way) and shake you out of bad habits without pulling their punches. Sometimes people who try to be too kind are not actually doing you a favor. A strong critique partner will be prepared to tell you honestly what you’re doing wrong.

Professional support, friendship, and critiquing are one of the best ways to “pay it forward” in a field like fiction-writing that can feel incredibly isolating and emotional from time to time. Everyone has their good days and their bad days, and it’s important to be available to others and share around the goodwill on your own good days, because someone else is always sure to need to feel the love!

As a science fiction writer, what first attracted you to that literary tradition? Have you been a long-time sci-fi reader?Other than

"Star Wars," "Star Trek" and

"Doctor Who" (the original series as well as the reboot), I wasn’t a huge sci-fi fan growing up. I certainly didn’t read sci-fi books. That felt like the dominion of the “male” complement in my family.

It was when I started writing that I became attracted to the genre and began to read anything I could get my hands on both in the YA and adult sci-fi areas. I spent several years reading everything from the more “classic” canon (

Asimov,

Philip K. Dick,

Heinlein,

Bradbury, Willis, etc) to some of the more recent writers (

Nalo Hopkinson,

N.K. Jemison,

Ann Aguirre,

Karen Lord,

John Scalzi).

Margaret Atwood

Margaret Atwood has also written some amazing dystopias in recent years, not to mention her classic

The Handmaid’s Tale (McClelland and Stewart, 1985). While many agents and editors talk about the death of the YA dystopian craze since the

Hunger Games and

Divergent frenzy seems to be playing out, I still feel that dystopian narratives have a lot to tell us.

Emily St. John Mandel’s recent take on a dystopic future after a plague has killed off most of the earth’s population

(Station Eleven) is a powerful contemporary musing on the nature of humanity, using a dystopian society in new and unexpected ways to achieve that end.

One of the things I like best about sci-fi is that it’s one of the most effective ways to ask foundational “what if” questions about human nature. Sci-fi writers can pick an element of our world and change it to ask “what would happen if [fill in the blank].”

For example, what would happen if …

a) society was divided into factions based on personality types?

b) criminals were released into the public with their skin stained different colors to denote their crimes?

c) technology became so advanced that we could no longer tell humans apart from androids?

d) the earth become so polluted or over-populated that humans needed to find a new home?

* Bonus points for naming at least one book/story that matches each of these descriptions. Suggested answers below.The sky is not even a limit with sci-fi. Not only are these kinds of stories fun and engaging (if written well), but they also raise issues about who we are at the most fundamental level.

Taking as an example the popular conceit of humans colonizing another planet, not only can this narrative device play a “what if” role about the future, but it also may give us insights about the past.

What have humans actually done in the past when expanding their territories on earth and encroaching on lands inhabited by others, human and/or non-human?

Ray Bradbury plays this idea out on many levels in

The Martian Chronicles, where the colonization of Mars and the Martian-human relationships can stand in for a variety of events that have already taken place within the confines of our own planet.

In my debut sci-fi novel for YA readers,

Inside the Palisade, I pose the question: What would happen if men had been banned from society and women reproduced through an artificial insemination procedure using stored genetic material?

|

| K.C. named Omega/Meg after her daughter (shown at the writing desk). |

In this all-female society men have been demonized (literally referred to as “demen”) as the cause of a great apocalypse that has brought humanity to the brink of extinction. Teen protagonist (Omega/Meg) comes across a young man who has been hidden within the walls of the city, and he isn’t what she expected. She is forced to question everything she’s been told about the differences between men and women and ultimately learns the truth about why the men were blamed for everything that went wrong.

The men here stand in for the “other.” Because Caucasian men are typically not thought of as an oppressed group in a western society, the set-up is a non-threatening lens through which to confront issues of “difference.” The device can invite readers to think about oppression or victimization of others hopefully without the narrative seeming overly preachy or judgmental. It takes a weird situation that would likely never happen in real life (my “what if”), and use it to encourage readers to think about why we dislike or fear people who are different, why we sometimes think of others as “less than” ourselves.

Good sci-fi gives us the opportunity to turn a real world problem on its head, or at least look at it through a new prism, so we can encourage readers to think about it from a new perspective while telling an engaging and unusual tale in the process. I love all genres and am a very eclectic reader, but I have a special place in my heart for sci-fi because of the amazing perspectives it can bring to us all.

* (a) Divergent by Veronica Roth; (b) When She Woke by Hillary Jordan; (c) Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep? by Philip K. Dick; (d) The Martian Chronicles by Ray Bradbury.

|

| Writer cats on the job, so to speak. |

Cynsational GiveawayEnter to win one of three signed copies of

Inside the Palisade by

K.C. Maguire (Lodestone, 2015). Author sponsored. Eligibility: international.

a Rafflecopter giveaway

By

Cynthia Leitich Smithfor

CynsationsLaura A. Woollett is the first-time author of

Big Top Burning: The True Story of an Arsonist, a Missing Girl, and The Greatest Show On Earth (Chicago Review Press, June 1, 2015). From the promtional copy:

Big Top Burning investigates the 1944 Hartford circus fire and invites readers to take part in a critical evaluation of the evidence

The fire broke out at 2:40 p.m. Thousands of men, women, and children were crowded under Ringling Brothers and Barnum & Bailey’s big top watching the Flying Wallendas begin their death-defying high-wire act. Suddenly someone screamed “Fire!” and the panic began. By 2:50 the tent had burned to the ground. Not everyone had made it out alive.

With primary source documents and survivor interviews, Big Top Burning recounts the true story of the 1944 Hartford circus fire—one of the worst fire disasters in U.S. history. Its remarkable characters include Robert Segee, a 15-year-old circus roustabout and known pyromaniac, and the Cook children, Donald, Eleanor, and Edward, who were in the audience when the circus tent caught fire. Guiding readers through the investigations of the mysteries that make this moment in history so fascinating, this book asks: Was the unidentified body of a little girl nicknamed “Little Miss 1565” Eleanor Cook? Was the fire itself an act of arson—and did Robert Segee set it? Big Top Burning combines a gripping disaster story, an ongoing detective and forensics saga, and World War II–era American history, inviting middle-grades readers to take part in a critical evaluation of the evidence and draw their own conclusions.How did you approach the research process for your story? What resources did you turn to? What roadblocks did you run into? How did you overcome them? What was your greatest coup, and how did it inform your manuscript? |

| Laura at the circus |

When I wrote the first draft of Big Top Burning, a nonfiction account of the 1944 Hartford circus fire, I had only dipped a toe into the giant pool of research that was to inform the final book.

I began the project in graduate school as an independent study in writing nonfiction for young people. That summer, I researched and wrote the entire first draft!

Of course, this was before I was married, before I owned a house, and before I had a child. My research consisted of reading the three (at the time) nonfiction books for adults on the subject, and reading every newspaper article on the fire from 1944 to date that I could find – mostly from the

"Hartford Courant" and the now defunct "Hartford Times."

The best thing I did was to interview a few survivors of the fire. They’d been children at the time and were so gracious in sharing the stories of their narrow escapes.

The interviews were gold. However, the newspaper articles, while primary sources, often held inaccurate information. The disaster happened quickly, and as reporters rushed to get information to the public, all sorts of false information found its way into their stories. And the adult books were secondary sources. I needed to form my own conclusions about the tragedy and the mysteries that surrounded it.

Then in 2009, I won the

SCBWI Work In Progress grant for nonfiction, and that gave me the inspiration to keep going and to dig deeper. I used the money to travel to Hartford where I discovered the extensive circus fire archives at the

Connecticut State Library. I spent several weekends at the library, diving into boxes of police records and witness statements, looking at crime scene photos, and even listening to a tape-recorded interview with the suspected arsonist, Robert Segee.

I’d be immersed for five hours at a time, and when I left I was exhausted, hungry (no food allowed in the archives area), and feeling victorious every time. I truly felt like a detective, collecting the clues to form a complete picture of the events that happened at the circus that day. Thank goodness for the librarians who collected and cataloged boxes and boxes of materials on the circus fire. It’s really due to them that authors like me are able to write such complete accounts of the tragedy.

As I continued to revise and send my manuscript to various agents and publishers, I interviewed more survivors. Interestingly, they seemed to appear wherever I went.

At the

Boston Public Library, a gentleman who saw my research materials spread out on a table stopped to tell me his tale of survival. When my father was recovering from heart surgery at

Hartford Hospital, he discovered his roommate was a survivor. My high school chemistry teacher (who always told us to keep our backpacks out of the aisles) shows up in one of the photos in my book. And I was able to interview my fifth grade teacher, who had been in the hospital having his tonsils out when they brought the first burn victims in.

I feel honored to be entrusted with their stories and proud to have written a book that will pass on the story of the Hartford circus fire to future generations.

|

| Memorial to the Hartford circus fire victims, built on the former circus grounds. The bronze medallion indicates the location of the center pole of the big top tent. |

How did you go about identifying your editor? Did you meet him/her at a conference? Did you read an interview with him/her? Were you impressed by books he/she has edited?When I sent out my manuscript on submission, I had done my research. (I’m a member of

SCBWI after all!) I began by querying agents who represented nonfiction authors, and I looked specifically at those who had worked with narrative nonfiction for older readers. I got some great feedback but no takers.

I turned to querying editors directly, trying all my contacts through writer friends and through SCBWI. Still lots of lovely rejections.

But I had my eyes open. I snoop in the backs of books to find out the names of the author’s agent and editors, which are often listed in the acknowledgements. I read quite a few blogs about writing and books for kids and always make note of agents or editors who publish work similar to mine, or work I think I’d like to write in the future.

It was on Cynsations that I found

a New Voices post by editor Susan Signe Morrison, who with author Joan Wehlen Morrison, wrote Home Front Girl (Chicago Review Press, 2012), a diary of everyday life of an American girl growing up in the years leading up to WWII.

Because the book was for an older audience, nonfiction, and about the same era as mine, I thought I’d query her acquiring editor,

Lisa Reardon at Chicago Review Press.

Two months after my query, Lisa sent me an offer letter.

After this experience I truly believe that if you write a good book, you will find a home for it—you just have to keep your eyes open and stay persistent. I wrote the first draft of Big Top Burning in the summer of 2005 and just a mere ten years later, I’m incredibly proud of its debut in 2015!

Cynsational NotesFor more information on the Hartford circus fire, visit

circus fire historian, Mike Skidgell.

By

Cynthia Leitich Smithfor

CynsationsStephanie Lyons is the first-time author of

Dating Down (Flux, 2015). From the promotional copy:

At Café Hex, Samantha Henderson can imagine being the person she really wants to be. It’s her place to daydream about going to art school and getting away from her politician father. It’s her place to imagine opening herself up to a new kind of connection, away from her family and the drama of high school.

Enter X—the boy she refuses to name. He’s older, edgy, bohemian . . . in short, everything she thinks she needs. Her family and friends try to warn her that there may be more to him than she sees, but still she stays with X, even as his chaos threatens to consume them both.

Told in waves of poetry—whispering, crashing—Dating Down is a portrait of exhilaration and pain and the kind of desire that drives a girl to risk everything.In writing your story, did you ever find yourself concerned with how to best approach "edgy" behavior on the part of your characters? If so, what were your thoughts, and what did you conclude? Why do you think your decision was the right one?I did struggle with how much to tell. My story is about a girl who spirals downward while in a bad relationship. It’s odd because—as far as the drugs and partying—I didn’t feel I needed to censor. But the sex, well, that was the part I wrote around for many edits until finally realizing it just wouldn’t be honest if I didn’t go there. So I did. And it hasn’t been a problem out in the real world with readers.

I guess my new mantra is anytime I take off my seventeen-year-old hat and put on my writer’s hat, I’m doing a disservice to the story.

As someone with a MFA in Writing for Children (and Young Adults), how did your education help you advance in your craft? What advice do you have for other MFA students/graduates in making the transition between school and publishing as a business?My MFA made all the difference. I was a sponge while I was at

Vermont College of Fine Arts. Time there is an endless source of creative inspiration and information: The lectures and discussions. Talking about books. Why you did or didn’t like a particular one. Turning something in on a monthly basis and knowing someone’s on the other side ready to read it and help you make it better.

All these things gave me “aha” moments. And the people I met were super talented and supportive. I didn’t just gain a degree, I gained lifelong writing friends.

As for advice for other MFA students making the transition, I’d definitely say, know that when you’re creating something that is the creative process. Once you create it and turn it over to an agent or editor that is the business process.

The creative process is personal. The business process isn’t. Learn to separate the two and you will have a much easier time.

|

| Ruby is a vital part of the creative process. |

By

Cynthia Leitich Smithfor

CynsationsMaggie Lehrman is the first-time author of

The Cost of All Things (Balzer + Bray/HarperCollins, 2015). From the promotional copy:

What would you pay to cure your heartbreak?

Banish your sadness?

Transform your looks?

The right spell can fix anything…

When Ari’s boyfriend Win dies, she gets a spell to erase all memory of him. But spells come at a cost, and this one sets off a chain of events that reveal the hidden — and sometimes dangerous — connections between Ari, her friends, and the boyfriend she can no longer remember.

Told from four different points of view, this original and affecting novel weaves past and present in a suspenseful narrative that unveils the truth behind a terrible tragedy. Part love story, part mystery, part high-stakes drama, The Cost of All Things is the debut of an extraordinary new talent.What inspired you to choose the particular point of view featured in your novel? What considerations came into play? Did you try the story from a different point of view at some point? If so, what made you change your mind?When I started writing The Cost of All Things (way before it had a title, even), the only thing I knew was that Ari had chosen to forget her boyfriend Win, who had died. I wrote nearly a hundred pages from just her point of view as she attempted to navigate the world without part of her memory.

Then I started my final semester at

Vermont College of Fine Arts with

Tim Wynne-Jones as my advisor.

Tim took a look at this 100 pages and got very concerned. How could I convey anything about Win, about Ari herself, if she doesn't actually remember him? How is the reader supposed to understand this world or connect to the characters?

I knew Tim was right, but I didn't know what to do about it. Switch to an omniscient third person? Start the story earlier?

Give up, cry, take a nap?

So I put the story aside for a year as I worked on other things, and when I came back to it, I started thinking about the other people in this world, and how they would be affected by Win's death.

Partly just for me, I wrote in other voices, basically starting the story over from the beginning. And as the other characters' wants and needs came into focus, I knew their stories were an important part of Ari's, even though she might not know it (yet). The interconnectedness of these characters became a driving force of the book. How does one person's actions affect the others? What do they uncover, the closer they get?

At an early point, there were as many as seven or eight points of view. But I fairly quickly narrowed it down to the four in the book: Ari, Markos, Kay, and Win, all in first person.

I've read interviews with

Jandy Nelson where she talked about how she wrote the absolutely brilliant

I'll Give You the Sun (Dial, 2014), which has two first-person narrators: she drafted straight through with one voice, and then straight through with the other, interspersing them later.

I couldn't do exactly that, as these four stories were meant to ping off of each other and loop around, but I did find myself going on a run of three-to-four Markos chapters in a row, and then catching up with a handful of Ari or Kay chapters, and then a whole mess of Win scenes. (Win was easier to write straight through because his chapters were all, by necessity, flashbacks.)

This meant I had a big jumble of scenes and plots in no particular order, which led to a lot of sorting and finessing after the first couple of drafts. Hence the Big Plot Wall, or what was affectionately known in my apartment as the Serial Killer Wall, named after the obsessive charts you see on TV in the homes of serial killers and those who hunt them.

|

| The Big Plot Wall |

Each of the four characters' stories are so personal, and they're each so blinded by their own perspective (at least in the beginning) that first person always made the most sense to me. They deal with pain in different ways, which I found I could express in first directly -- as well as show how much of the story was about who knew what secrets when.

As a fantasy writer, going in, did you have a sense of how events/themes in your novel might parallel or speak to events/issues in our real world? Or did this evolve over the course of many drafts?My glimpse of this world began very small, with Ari and the spell she chose to take to forget Win.

I like to understand the characters before I do any larger-scale thinking about themes, or I can get bogged down with expressing ideas instead of exploring human behavior.

I completely understood why one girl would choose to eliminate the source of her pain -- isn't there something we all wish we could forget? -- and that moment of empathy made me want to know more about Ari and what happened to her. And so I had to dig in to the glimpse and expand it beyond Ari.

If Ari can take this spell, what else is true about this world? How does the magic work? What are its costs?

Once I started thinking about those questions -- how spells were made and taken and paid for, what the consequences would be, who took spells and why -- I started to see the types of parallels you could make to the real world: spells were shortcuts, a way to avoid moments or situations that might be difficult or painful. They gave you what you wanted, but what you wanted isn't always what you needed. There were parallels to performance-enhancing and recreational drugs, cheating, plastic surgery, and more.

This is not to say that using spells was always a bad idea; like in the real world with medical decisions or pain relievers or other important means of self-care, sometimes a spell could be a healthy choice. Hekame (what I called the practice of magic in this world) wasn't good or bad on its own, but could be used for good or bad based on the decisions of the characters. And it always has consequences.

As a side note, for a fascinating and very different way of looking at some of the same questions, especially when it comes to memory, I'd check out the excellent

More Happy Than Not by

Adam Silvera (Soho Teen, 2015). Part of the reason I love fantasy/science fiction (as it is in Adam's case) is that writers can answer similar questions in totally different ways.

I've always been fascinated by the way fantasy heightens and reflects the real world.

Ursula K. LeGuin said that fantasy stories "work the way music does: they short-circuit verbal reasoning, and go straight to the thoughts that lie too deep to utter."

Hekame was a way for me to talk about choices and consequences, things we in the real world have to face constantly, without having to name each of the parallels. There's room for the reader to fill in their own experience and intuition.

Cynsational GiveawayEnter to win a signed copy of

The Cost of All Things by

Maggie Lehrman (Balzer + Bray/HarperCollins, 2015). Author sponsored. Eligibility: continental U.S.

a Rafflecopter giveaway

By

Erin Hagar &

Joanna Gorham For

Cynthia Leitich Smith's

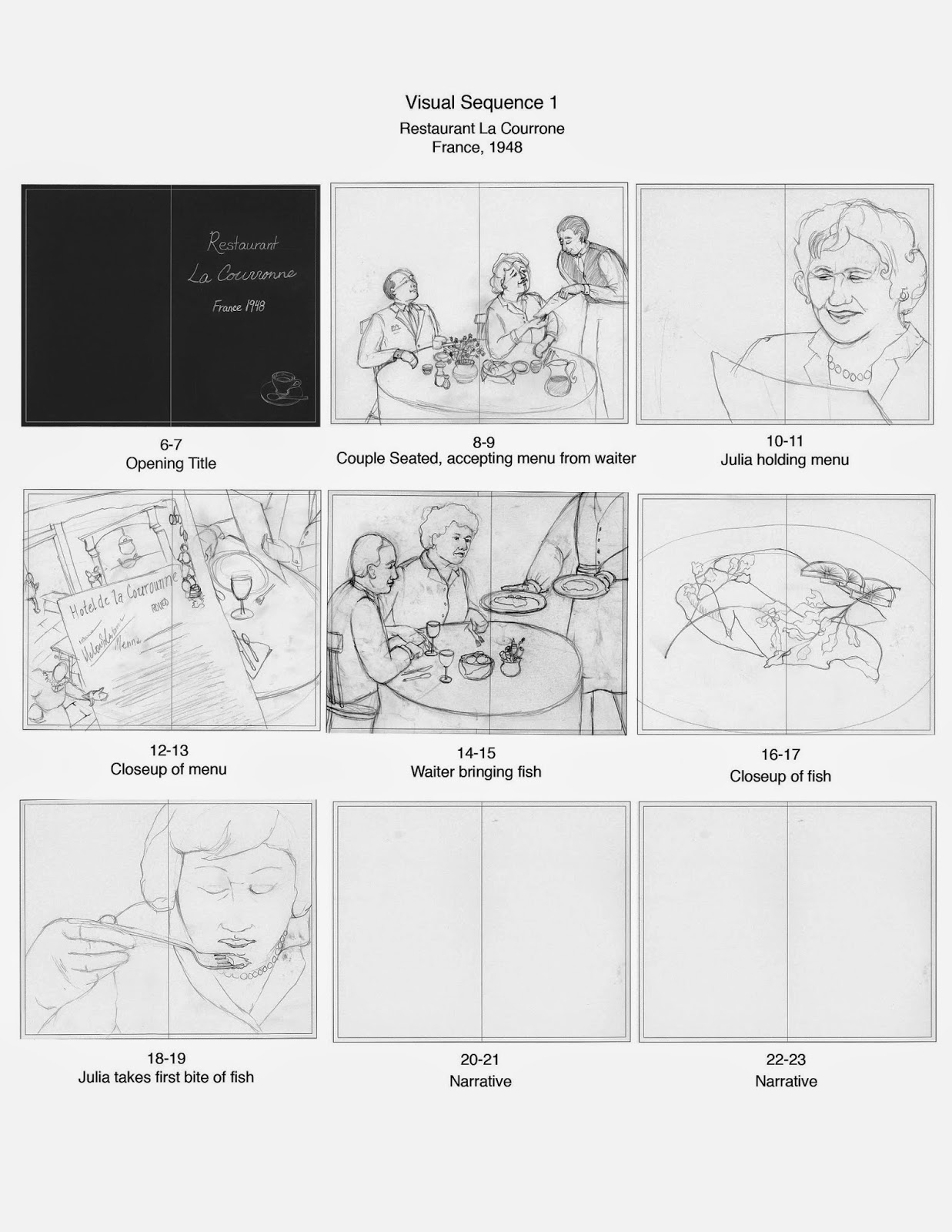

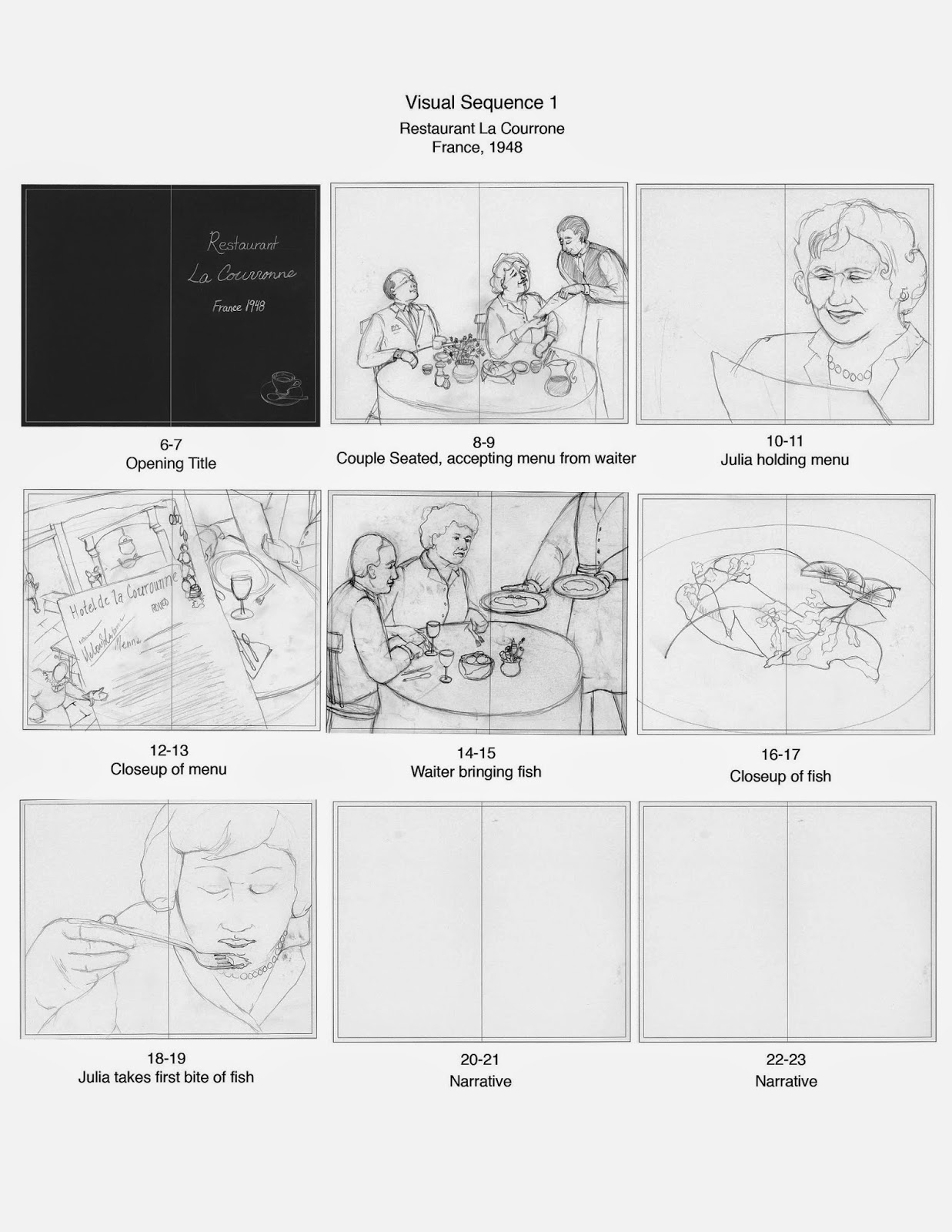

CynsationsJulia Child: An Extraordinary Life in Words and Pictures is by

Erin Hagar and illustrated by

Joanna Gorham (Duopress, 2015). From the promotional copy:

Julia Child knew how to have fun, and she also knew how to whip up a delightful meal.

After traveling around the world working for the U.S. government, Julia found her calling in the kitchen and devoted her life to learning, perfecting, and sharing the art of French cuisine.

This delicious, illustrated middle-grade biography is a portrait of the remarkable woman, author, and TV personality who captured our hearts with her sparkling personality. “Bon appétit!” What about Julia's life most resonated with you?EH: Julia didn’t find her true passion until she was almost forty. She worked hard at all the other jobs she had, but it took a long time to find the job that didn’t feel like work. I worry that today’s kids are pressured to excel at such a young age. I hope Julia’s experience speaks to them, as well.

JG: To achieve all that Julia did, she had to have courage, creativity and the willpower to withstand failure if things didn’t go as planned. I hope I can have the same strength that she showed throughout her life.

|

| Julia Child, First Bite by Joanna Gorham, reproduced with permission. |

How was this process different from other projects you've worked on?EH: I also write (but don’t illustrate) picture books. Folks like me are supposed to stay the heck out of the illustration process so the illustrator can add his or her creative genius to the work.

With this book, I was asked to help to map out what the visual sequences would include and provide visual information from my research. At first, I felt very hesitant about this, but that’s what the project and the timeline demanded. The beauty of the illustrations, however, is all Joanna. I don’t take one ounce of credit for that.

|

| storyboard |

JG: When I illustrate magazine articles, I’m looking to show details about the character that tell the viewer more than what’s in the text, while capturing one moment in time. In the Julia book, the chapters show an evolution of Julia’s life.

What were some of the biggest revisions you made?EH: Cutting, cutting and more cutting. I don’t remember most of what was cut (which means the edits were absolutely necessary) except for this one thing: There’s a long, convoluted, and funny story about how Julia flunked her final exam from Le Cordon Bleu. Word count got the best of us, so I’ll save it for school visits, I guess!

JG: Showing Julia change over the years and making sure she still looked like the same person was a challenge. I didn’t want to exaggerate her age to get the point across that she was aging, but she couldn’t look like she was thirty throughout the book. I painted and repainted her face a lot.

What was the most challenging aspect of this project?EH: Describing the cultural landscape of the 1950’s and '60’s in a child-friendly way was tough for me. Today, there’s a broader conversation about food and cooking than there was back then.

Also, kids today can watch an entire channel devoted to food and cooking. There were only three national channels during Julia’s time.

JG: The timeline, for sure.

After I finished an illustration, I sent it to the art director, who reviewed it with the Erin and the publisher, sent it back for revisions, and then it was sent it to the designer to include in the book.

My job was to try my best to keep up with the schedule.

What is your favorite illustration in the book?EH: The cover of the book really knocks my socks off, but the illustration of Julia holding her cookbook for the first time is my favorite.

This is my first book, so I can totally relate to the mix of emotions Joanna captured so beautifully.

JG: Julia’s recreated kitchen in the Smithsonian. Her own kitchen was such a personal part of her. Cooking wasn’t just a job, but a passion she took home after work.

The little girl is so excited to experience the intimate setting where Julia shared so much of herself with thousands of museum guests.

Cynsational NotesErin Hagar writes fiction and nonfiction for children and teens. She is a member of the

Society of Children’s Book Writers and Illustrators and holds an

MFA in Writing for Children and Young Adults from Vermont College of Fine Arts. She lives in Baltimore with her husband and two children. She has not yet trussed a chicken, but makes a mean molasses cookie. This is her first book.

As a child

Joanna Gorham traveled all over the world. She found a love for food, exploring, and storytelling. Now she tells her own stories through her watercolors in children’s books and family magazines. She recently won two of

Applied Arts Magazine’s Young Blood Awards, for the brightest up-and-coming talent. You can find her painting in a little red cottage on an island in the Pacific Northwest.

By

Cynthia Leitich Smithfor

CynsationsDanica Davidson is the first-time author of

Escape from the Overworld (Skyhorse, 2015). From the promotional copy:

Eleven-year-old Stevie, who comes from a long line of Steves, doesn't feel as if he fits in the Minecraft world. His father is great at building and fighting off zombies, but Stevie struggles in these areas. One day, when Stevie is alone in the field trying to build something new that will impress his dad, he discovers a portal into a new world.

Stevie steps out of a computer screen and into the room of eleven-year-old Maison, a sixth-grade girl who loves to build and create, but who is bullied and made an outcast by her classmates for not indulging in activities deemed "cool." Stevie is shocked by how different this world is, and Maison takes him under her wing and teaches him all about her world. The two become friends, and Maison brings Stevie to school with her.

Stevie is horrified to see there are zombies in the school He realizes that when he opened the portal, this allowed zombies to also enter the new world. More and more creatures are slipping out by the second, wreaking havoc on a world that has no idea how to handle zombies, creepers, giant spiders, and the like. Stevie and Maison must put their heads together and use their combined talents in order to push the zombies back into Minecraft, where they belong. As Stevie and Maison's worlds become more combined, their adventure becomes even more frightening than they could have imagined.When and where do you write? Why does that time and space work for you?I’ve always loved writing — I still have stories I dictated to my parents when I was three, or little notebooks I wrote in when I was so small I had to follow my mom around and ask her how to spell each word.

This continued on throughout the years, with me starting to write multiple novels in middle school. I like to write in a private area, usually with music playing. The music varies depending on the type of scene or book I’m writing.

For my book Escape from the Overworld, I got the contract before I’d written the book and the publisher wanted a quick turnaround of about six weeks.

There was definitely a moment of, “Six weeks – what have I gotten myself into?” But then I made myself plan.

Working as a journalist has taught me that you sit down and you write your project; if breaking news is happening, your editor is not going to care if the Muse isn’t inspiring you that day.

I’d turned in a synopsis for the book, which is what led to the contract, so I spent the next week figuring out in my head the details of the scenes. The main characters are eleven, so I reread some writings I did at eleven to help me get back in the voice. The week after that, I made myself write at least 2,000 words at day on the manuscript before taking any breaks. I wrote more on the weekend or if the words were flowing extra well that day.

In one week, I had my rough draft of about 20,000 words. I gave it to some friends to help me edit (warning them it was called a rough draft for a reason), and waited till I got their edits back before I returned to the manuscript. Once I got their thoughts, I started my revisions and I made my deadline.

There were a number of things that were important to me while writing. I know some people might be quick to dismiss it as, “Oh, it’s just a Minecraft book,” but I wanted it to be more than that.

Since I notice a lot of Minecraft books (or even just adventure books in general) are male-dominated, I made sure my protagonists are male and female and on equal footing. I take on issues like bullying and the fears of going to a new school. I made the shop class teacher female, because I know many people would unconsciously picture a shop class teacher as being male. Both the main characters are from single-parent households, since I wanted to show that’s normal for many kids and nothing to be ashamed of.

As a result of my bullying and girl-power angles, the book has been included in an anti-bullying, girl-empowerment program called

Saving Our Cinderellas that aims to inspire young girls of color in cities around the country. I want the book to be fun — I end almost every chapter with a cliffhanger for a reason — but I also hope it can inspire young readers and touch them emotionally as well. It's my goal to write all different types of books for all different ages.

As someone with a full-time day job, how do you manage to also carve out time to write and build a publishing career? What advice do you have for other writers trying to do the same?This is kind of a trick question for me, because writing is my full-time day job, but it’s journalism.

Hear me out.

My fantasy was to publish novels and become a professional writer that way, but as many writers know, that’s easier said than done. When I was in high school, I had to start earning my own money because of financial and family issues. Like many a naive young writer, I submitted stories to

"The New Yorker" and other such prestigious places. And like many a naive young writer, I have some fabulous rejection letters from the "The New Yorker" and other such prestigious places.

I realized that wasn’t going to work, so I started out smaller, writing for local newspapers. Once you’ve published things professionally, other places will take you more seriously. I would take samples of my published work and send them to bigger and bigger places.

|

| Porthos |

My interest in anime and manga had me writing about the subject for local papers, and then I used that to get me in

Anime Insider, which led to

Booklist,

Publishers Weekly,

CNN,

The Onion,

Los Angeles Times and other places. (I know this sounds really quick, but I can tell you it actually took years, and I got many rejections in the meantime.)

I even found opportunities to write the English adaptation of Japanese graphic novels for the publishing company

Digital Manga Publishing.

At first I was working other part-time jobs to supplement my income, but within a few years I became a full-time writer. Every single day I wrote articles and sent out more submissions.

I began to be known as an expert on manga and graphic novels, and this led me to writing for MTV, which at the time had me reporting on superhero comics being made into movies. I love writing for

MTV News, and now I cover social justice issues for them, which means I write about things like philanthropy, activism and advocacy with causes that matter to young people. I was part of a small group of MTV writers to receive a Webby Honor for Best Youth Writing.

All of this helped me hone my craft, get my name out there, and pay the bills.

When I got my agent not long ago, he was very impressed to see a twenty-something who’d sold more than a couple thousand articles to big-name places.

Then while he was shopping around a YA series of mine, Skyhorse Publishing approached me, wanting a manga art guide. Of course I was thrilled and grateful! Next they asked me if I could write some sort of Minecraft book, which led me to pitch Escape from the Overworld. The manga book will be out soon, and I just finished my rough draft for my sequel to Escape from the Overworld, which has the planned title Attack on the Overworld.

I still haven’t been in "The New Yorker," but that’s okay.

By

Cynthia Leitich Smithfor

CynsationsReem Faruqi is the first-time author of

Lailah’s Lunchbox, illustrated by

Lea Lyon (Tilbury House, 2015). From the promotional copy:

Lailah is in a new school in a new country, thousands of miles from her old home, and missing her old friends. When Ramadan begins, she is excited that she is finally old enough to participate in the fasting but worried that her classmates won't understand why she doesn't join them in the lunchroom. Lailah solves her problem with help from the school librarian and her teacher and in doing so learns that she can make new friends who respect her beliefs. This gentle, moving story from first-time author Reem Faruqi comes to life in Lea Lyon's vibrant illustrations. Lyon uses decorative arabesque borders on intermittent spreads to contrast the ordered patterns of Islamic observances with the unbounded rhythms of American school days. As someone who's the primary caregiver of children, how do you manage to also carve out time to write and build a publishing career? What advice do you have for other writers trying to do the same?Trying to write and mothering young children can be very tricky! I have a two-year-old and four-year-old and have learned that you get better at working through interruptions. When I’m writing, I’m usually receiving interruptions from my children to take them to the bathroom, for another snack … the list goes on!

When my four-year-old is at school, I have my interruptions cut in half with just my two-year-old's needs. That's when I feel I get the most writing done.

I do try to write sometimes at night when the children are asleep and find it semi-successful. I find I work best during daylight. I love natural light and find it conducive to working and getting my ideas flowing.

At night, it is easy to feel tired after a busy day!

When I quit teaching to stay home with my children, I wrote a lot of children's manuscripts when my first child was a baby. She slept a lot during the day so I enjoyed getting that time to write.

Those stories didn't make it in the publishing world, but through them I now found a stronger voice that works for me.

|

| "Writing" her name with Webdings |

I do think it's important though to rest when your children are resting as that time is precious and when your mind is rested, it is easier to write. Sometimes whole stories will pop in my head when I am doing something random like getting my children ready for bed. It's as if I can visualize the story, the words, the illustrations, but sometimes when I sit down at the computer, it is frustrating when that story disappears! But if it's a good story, I believe it will resurface.

The title for my story, Lailah's Lunchbox, popped into my head when I was cooking: I thought it would be fun to write a Ramadan story about a child who "forgot" their lunchbox every day during Ramadan. I wrote the title on a sticky note and put it away for some time before coming back to it.

For those trying to write and raise children, I would tell them there is no such thing as having it all! You may have a great manuscript you’re working on but you will be eating left-overs for dinner for the third day in a row and children that need a bath! Or you may be itching to write a story, but find yourself caught up in bathing children, cooking food, laundry, dropping and picking up children from school, etc!

Something has got to give way when you write. Sometimes I may be caught up in a story and look around at my house and children and think What Happened?!

|

| This happened when I was writing once! |

At those times, find reassurance in your words that you have just worked on and know that because of entropy, your house will continue to keep getting dirty. Putting your words out there takes work and in due time your work will pay off!

Could you tell us the story of "the call" or "the email" when you found out that your book had sold? How did you react? How did you celebrate?I got a flurry of emails until the "Yes" email!

I made a list of six agents and six publishers to send Lailah’s Lunchbox to. I mailed the manuscripts on May 30 and tried to distract myself with other things. On June 16, I received an email with the subject ‘Your Manuscript’ in my inbox. That was enough to make my insides leap!

The email was from Fran Hodgkins, the Director of Editorial Design at Tilbury House, saying I had sent my manuscript to their old mailing address and that it had been re-routed to their new address.

|

| This is the wrong address for Tilbury House! |

Fran said she enjoyed reading it and was sharing it with the co-publishers, Jon Eaton and Tris Coburn, as well as Audrey Maynard, the editor. She went on to say my story was a unique take on Ramadan and she was glad I thought of it. She wanted to know if I had received a response from any other publishers as yet.

I wrote back saying I hadn’t heard a response yet and then went on to forward the email to my aunt who was the person who had encouraged me to send in Lailah’s Lunchbox. She was just as excited as I was!

I checked my email a lot that week but no response. A week later I followed up with Fran asking if she had any response from her co-publishers to which she responded that they were meeting the next day to discuss my story.

I didn’t hear anything from them the next two days. Then on June 24, Tilbury House Publishers followed me on Twitter (

@ReemFaruqi). At this point, I started to get more hopeful.

I couldn’t wait anymore so emailed Fran to see if there was any updated to which I got the yes email on June 26:

I was going to wait and have our children's book editor call you, but I'll take this opportunity to say that we really like your manuscript and would like to publish it.

I'm CCing Audrey on this email, as she is the one who'll be working with you closely and our publisher, Tris Coburn, will be in touch to talk terms.

If that all sounds good to you, let me know....

I then took the next 20 minutes to celebrate. I couldn’t believe that I finally got a Yes!

My two-year-old had just gone down for a nap so I couldn’t tell her and I had to celebrate semi-quietly. My husband was teaching so couldn’t phone him up to tell him. My four-year-old was at school so couldn’t tell her either.

So I just jumped around for a minute before calling my aunt who was just as excited as I was, and then my mother who knew when I told her to “Guess What?” that I’d gotten a book deal offer! I wanted to email Fran back with a hundred exclamation marks saying:

THIS SOUNDS AMAZING!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!

But once I’d composed myself, I wrote:

Hi Fran,

Thanks for the quick reply. I couldn't wait long enough for the editor to call me. Yes, this sounds amazing and I so excited!

Looking forward to talking with Tris Coburn.

Reem

Within the next few days, I spoke with the publisher Mr. Tris Coburn and Ms. Audrey Maynard, the children’s book editor. It felt surreal to be talking to people whose names I had admired.

That night I went over to my mother’s house and we had a cozy family dinner to celebrate!

|

| Editing time! |

By

Cynthia Leitich Smithfor

CynsationsSarah McGuire is the first-time author of

Valiant (Egmont/Lerner, 2015). From the promotional copy:

Reggen still sings about the champion, the brave tailor. This is the story that is true.

Saville despises the velvets and silks that her father prizes far more than he’s ever loved her. Yet when he’s struck ill she’ll do anything to survive–even dressing as a boy and begging a commission to sew for the king.

But piecing together a fine coat is far simpler than unknotting court gossip about an army of giants, led by a man who cannot be defeated, marching toward Reggen to seize the throne. Saville knows giants are just stories, and no man is immortal.

Then she meets them, two scouts as tall as trees. After she tricks them into leaving, tales of the daring tailor’s triumph quickly spin into impossible feats of giant-slaying. And stories won’t deter the Duke and his larger-than-life army.

Now only a courageous and clever tailor girl can see beyond the rumors to save the kingdom again.

Perfect for fans of Shannon Hale and Gail Carson Levine, Valiant richly reimagines "The Brave Little Tailor," transforming it into a story of understanding, identity, and fighting to protect those you love most.Was there one writing workshop or conference that led to an "ah-ha!" moment in your craft? What happened, and how did it help you?I think it came in stages for me. I was one of the lucky writers included in the

Nevada SCBWI Mentor Program.

Harold Underdown chose me as one of his mentees, and for six months, we worked though my novel. I think my biggest takeaway was tackling the middle of the novel and keeping it from sagging.

Even though I had to slide that novel, under the metaphorical bed, I had a much better understanding of story structure. And I used it in Valiant, making sure I had a tent pole of tension to hold up the center of the story.

My next jump was in a

Highlights Workshop with

Patti Gauch. She taught (among other things) about going far enough emotionally, about reaching a transcendent moment of fear or hope or joy. She taught me to watch for those places in the story that already meant something to me. I learned to circle back to those places and dive into the emotion of that moment.

I think as writers, we're afraid of our emotion in a scene seeming cheesy or overwrought. And from that place of fear, we keep our emotion on a tight rein. I would have said I was being subtle, but the truth was that I was scared– scared of purple prose and people laughing at over the top scenes. When I was afraid, and didn't go far enough, my writing came across as insincere or insubstantial.

And ... here's the secret: it was. I was too scared to reveal the substance of that emotion. I was too afraid to be truly sincere. My fear of emotional triviality actually made my writing trivial.

But now I'm all better.

Ha.