History and poetry hardly seem obvious bed-fellows – a historian is tasked with discovering the truth about the past, whereas, as Aristotle said, ‘a poet’s job is to describe not what has happened, but the kind of thing that might’. But for the Romans, the connections between them were deep: historia . . . proxima poetis (‘history is closest to the poets’), as Quintilian remarked in the first century AD. What did he mean by that?

The post A history of the poetry of history appeared first on OUPblog.

Roman literature often derived from Greek sources, but took Greek models and made them its own. It includes some of the best known classical authors such as Ovid and Virgil, as well as a Roman emperor who found time to write down his philosophical reflections.

Saint Augustine’s Confessions by Saint Augustine

Augustine was a gifted teacher who abandoned his secular career and eventually became bishop of Hippo. His Confessions are a remarkable record of his wrestlings to accept his faith, his struggles to overcome sexual desire and renounce marriage and ambition. His final moment of conversion in a Milan garden is deeply moving.

On Obligations by Cicero

The great Roman statesman Cicero lived at the center of power. He was an advocate and orator as well as philosopher, who met his death bravely at the hands of Mark Antony’s executioners. On Obligations was written after the assassination of Julius Caesar to provide principles of behavior for aspiring politicians. Exploring as it does the tensions between honorable conduct and expediency in public life, it should be recommended reading for all public servants.

The Rise of Rome by Livy

The Roman historian Livy wrote a massive history of Rome in 142 books, of which only 35 survive in their entirety. In the first five books, translated here, he covers the period from Rome’s beginnings to her first major defeat, by the Gauls, in 390 BC. Among the many stories he includes are Romulus and Remus, the rape of Lucretia, Horatius at the bridge, and Cincinnatus called from his farm to save the state.

On the Nature of the Universe by Lucretius

Lucretius lived during the collapse of the Roman republic, and his poem De rerum natura sets out to relieve men of a fear of death. He argues that the world and everything in it are governed by the laws of nature, not by the gods, and the soul cannot be punished after death because it is mortal, and dies with the body. The book is an astonishing mix of scientific treatise, moral tract, and wonderful poetry.

Meditations by Marcus Aurelius

Roman emperor Marcus Aurelius was probably on military campaign in Germany when he wrote his philosophical reflections in a private notebook. Drawing on Stoic teachings, particularly those of Epictetus, Marcus tried to summarize the principles by which he led his life, to help to make sense of death and to look for moral significance in the natural world. Intimate writings, they bring us close to the personality of the emperor, who is often disillusioned with his own status, and with human life in general.

Metamorphoses by Ovid

The Metamorphoses is a wonderful collection of legendary stories and myth, often involving transformation, beginning with the transformation of Chaos into an ordered universe. In witty and elegant verse Ovid narrates the stories of Echo and Narcissus, Pyramus and Thisbe, Perseus and Andromeda, the rape of Proserpine, Orpheus and Eurydice, and many more.

Agricola and Germany by Tacitus

Tacitus is perhaps best known for the Histories and the Annals, an account of life under emperors Tiberius, Claudius and Nero. The shorter Agricola and Germany consist of a life of his father-in-law, who completed the conquest of Britain, and an account of Rome’s most dangerous enemies, the Germans. They are fascinating accounts of the two countries and their people, the northern ‘barbarians’. Later, German nationalists attempted to appropriate Germania in support of National Socialist racial ideas.

Georgics by Virgil

The Georgics is a poem of celebration for the land and the farmer’s life. Virgil doesn’t romanticize, rather he describes the setbacks as well as the rewards of working the land, and provides memorable descriptions of vine and olive cultivation, raising crops, and bee-keeping. It is both a practical agricultural manual and allegory, and brings the ancient rural world vividly to life.

Aeneid by Virgil

The story of Aeneas’ seven-year journey from the ruins of Troy to Italy, where he becomes the founding ancestor of Rome, is a narrative on an epic scale. Not only do Aeneas and his companions have to contend with the natural elements, they are at the whim of the gods and goddesses who hamper and assist them. It tells of Aeneas’ love affair with Dido of Carthage and of Aeneas’ encounters with the Harpies and the Cumaean Sibyl, and his adventures in the Underworld.

Heading image: Roman Virgil Folio. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.

The post A reading list of Roman classics appeared first on OUPblog.

By Jessica H. Clark

Just east of downtown Tallahassee, Florida, there is a small city park known as “Old Fort.” It contains precisely that – a square of softly eroding earthworks (all that’s left of the fort) along with a few benches placed benignly in the shade of nearby oak and pine trees. The historical marker in the park offers some explanation:

“This earth work located on ground once part of the plantation of E.A. Houston…who commanded the Confederate artillery at the Battle of Natural Bridge, is a silent witness of the efforts of the citizens of Tallahassee to protect the capitol of Florida from capture when threatened by federal troops under General John Newton. Newton’s force landed at St. Marks light house [sic] and advanced up the east side of the St. Marks River, only to be decisively repulsed at Natural Bridge on March 6, 1865, by a hurriedly assembled Confederate force commanded by General Sam Jones, which included a company of cadets from the West Florida Seminary, now Florida State University.”

Civil War marker in Old Fort Park, Tallahassee, Florida. Photo by Jessica H. Clark. Used with permission.

So the marker claims the park as a victory monument of sorts. It was here in 1865 that soldiers of the army of the Confederate States of America waited for an invading force that never came. The interpretive marker is genteel and uncommitted, allowing for assumed knowledge on the part of its reader to complete the story it would rather not to tell. So in some ways, the work of remembering our Civil War is not unlike dinner at Downton Abbey — words need not match their meanings to be perfectly well understood, if understood differently, by those who hear them.

The Romans knew that remembering was never that simple. The Roman historian Tacitus wrote a wonderful piece describing events in the year 69 or 70 C.E., which illustrates what we risk when we try to make the ground bear witness to a convenient past. According to Tacitus’s account, a man named Julius Civilis was leading a rebellion against Roman occupation east of the Rhine. He attacked two Roman legions and forced them back to their camp at Vetera (modern Xanten), and eventually convinced them, after a lengthy siege, to surrender in exchange for their lives. However, several of Civilis’s allies broke the truce and ambushed the retreating Romans, killing many and driving the rest back to Vetera. Civilis and his men finished off these unarmed Romans and burned the camp to the ground.

Table-top model of Roman Xanten (Castra Vetera), Archäologischer Park Xanten. Photo by Аlexej Potupin via Wikimedia Commons.

Not long afterwards, as Civilis and his men prepared for another battle at Vetera, Tacitus describes him giving a speech to his men in which he “[calls] the site of the battle a ‘witness to valor’” and that “they stood on footprints of glory, walking on the ashes and bones of legions.” But Civilis errs; having flooded the original battle site to disadvantage the Roman legions, Civilis knows that his speech does not match reality. A poor student of history, he is too eager in his facile assumptions of the relationship between physical remains and the memory of war.

The sense of physical connection is important, though, and so in place of real ashes beneath their feet, he gives his men the next best thing. He asks them to imagine the bones of their enemies, just as their commander imagines that their bloody indiscipline could be monumentalized into a glorious victory. Tacitus creates a striking metaphor for civil war commemoration: imaginary monuments invoking false memories, inspiring fictive reinterpretations of a better past that never was.

This, of course, never does anyone any good. Civilis was bound to fail because he did not learn from his mistakes, and did not learn from them because he chose, instead, to tell a story where they had no place.

Thus can the lies we tell ourselves about our wars exact a higher price, in the long term, than the conflicts themselves. This isn’t just ancient news, either; as recently as 2000, the US Congress asked the Department of the Interior to “compile a report on the status of our interpretation of battlefield sites.” The National Park Service conducted an investigation and concluded that it was time to “develop a new paradigm” for the national commemoration of the American Civil War. The report sets forth, as an exemplar, Harpers Ferry, Virginia, where (what is often seen as) a pro-slavery monument was restored but matched by an interpretive plaque commemorating, effectively, the ways in which the stories we tell now are different from those we have told in the past.

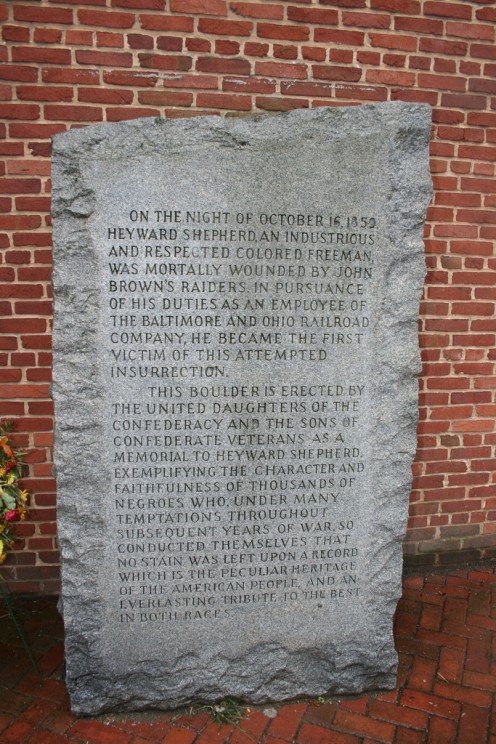

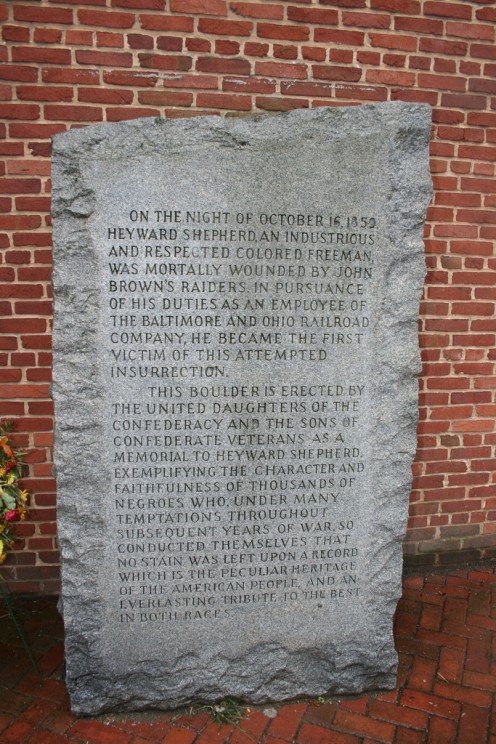

This monument in Harpers Ferry, West Virginia, which commemorates free black man Heyward Shepherd — killed during John Brown’s raid in 1859 — for his “faithfulness” to the Confederacy, has been the subject of debate for several decades. CC BY-NC 2.0, photo by Slave2TehTink via Flickr.

The pairing of monument and plaque, unsurprisingly, caused enormous controversy. And what it underscores is, I think, one of Tacitus’s points for the preservation of civil society: the very aspects of the past that threaten our foundational illusions are the ones that have the most to offer our future.

The marker at the Old Fort in Tallahassee calls the earthwork a “silent witness,” an idea also deployed with great force in Eric Bogle’s 1976 World War I song “No Man’s Land”:

But here in this graveyard that’s still No Man’s Land

The countless white crosses in mute witness stand

To man’s blind indifference to his fellow man

And a whole generation that was butchered and damned.

In March of 2014, President Obama spoke at Flanders Field American Cemetery. While some parts of his remarks were deeply moving, at one point he invoked the hundreds of thousands of dead who lay beneath that ground: “Belgian and American, French and Canadian, British and Australian, and so many others…while they didn’t always share a common language, the soldiers who manned the trenches were united by something larger — a willingness to fight, and die, for the freedom that we enjoy as their heirs.”

Robert Vonnoh (American, 1858-1933), “Coquelicots” (“Poppies”), 1890; retitled in 1919 as “Flanders – Where Soldiers Sleep and Poppies Grow.” Butler Institute of American Art, photo from Exhibition Catalogue Americans in Paris, Metropolitan Museum via Wikimedia Commons.

Those soldiers presumably would have died for freedom, as would the “so many others” (better known to history as Germans), had they been called to do so — but the First World War was not about that. We make false witness of the past and then wonder why it does not teach our children the truth; and while we may take some comfort from our consistency, Tacitus and the Park Service should remind us that we can do better.

Jessica H. Clark is Assistant Professor of Classics at Florida State University and the author of the book Triumph in Defeat: Military Loss and the Roman Republic.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only classics and archaeology articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

The post Wars and the lies we tell about them appeared first on OUPblog.