By Mary Pleiss

When I was a little girl, the witches I knew came from fairy tales. They were old, ugly, and mean–life ruiners who cast evil spells with no provocation. My young friends and I ran into the problem of the witch in our play. We didn’t want to meet a witch in a dark forest or a bright one, even if that forest was the pair of trees in our backyard. Certainly none of us wanted to be the witch. But we knew we had to have a witch. Witches made things happen, provided scary, shivery tension, and gave the good characters something to fight against and overcome.

When I was a little girl, the witches I knew came from fairy tales. They were old, ugly, and mean–life ruiners who cast evil spells with no provocation. My young friends and I ran into the problem of the witch in our play. We didn’t want to meet a witch in a dark forest or a bright one, even if that forest was the pair of trees in our backyard. Certainly none of us wanted to be the witch. But we knew we had to have a witch. Witches made things happen, provided scary, shivery tension, and gave the good characters something to fight against and overcome.

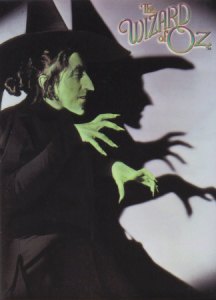

We often solved this problem by keeping the witch offscreen; we called out plot points detailing the unseen, unheard witch’s actions: “Now the witch is casting her spell. If you get to the swing set, you’re safe!” or, “You stepped into the witch’s clover patch–you’re trapped!” We could imagine the witch without casting her because we’d read stories and seen movies (mostly Disney movies and of course The Wizard of Oz). We knew witches well enough to weave them into our play without having to face the fact that we all had it in ourselves to be witches.

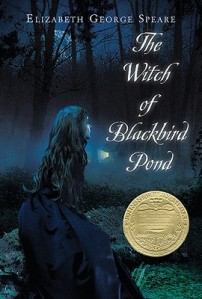

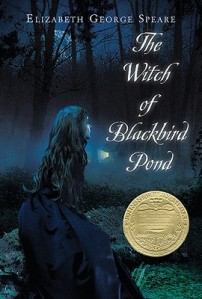

In sixth grade, I read Elizabeth George Speare’s The Witch of Blackbird Pond, and I started thinking about witches in a different way. What made the people of Wethersfield believe Hannah Tupper and Kit Tyler were witches, when any reader could see they weren’t magical or evil–just a little bit different? Why did their neighbors feel the need to banish or imprison them? If Hannah and Kit weren’t really evil, what did that say about the fairy tale witches I’d always feared and hated?

In sixth grade, I read Elizabeth George Speare’s The Witch of Blackbird Pond, and I started thinking about witches in a different way. What made the people of Wethersfield believe Hannah Tupper and Kit Tyler were witches, when any reader could see they weren’t magical or evil–just a little bit different? Why did their neighbors feel the need to banish or imprison them? If Hannah and Kit weren’t really evil, what did that say about the fairy tale witches I’d always feared and hated?

The witches in our fiction today are very different from those in fairy tales, and it turns out that even the Wicked Witch of the West has more complexity than I realized when I was growing up. I knew her from the movie, but reading the books as an adult, and learning more about the history of the Oz books in particular and witches–and those who were accused of witchcraft–in western culture has witches in a new light. L. Frank Baum was heavily influenced by his mother-in-law, Matilda Gage, who was an historian and feminist who promoted influential theories about women who were called witches in history. Baum had those theories in mind when he populated Oz with witches who were more dimensional than what had come before; they had backstories and motivations, and while some of them were evil, just as many were good.

Since Baum, of course, a number of children’s and YA writers have included witches–and women accused of witchcraft–in their stories. Whether bad, good, or somewhere in between, those witches have developed into characters with more depth and complexity than even Baum could have imagined. As societal attitudes about the roles of girls and women have evolved, fictional characterizations of witches have changed, and we can’t get away with taking the problematic witch offscreen or making her a one-dimensional villain. Now, when we write about witches, we work to make them as dimensional as all of our other characters, and our problem becomes the same as that we face with most other characters: how do we bring the witch to life?

Here are some suggestions and questions you can ask yourself if you’re including witchy characters in your fiction:

Consider doing some research into historical witches and witchcraft trials. You might find an angle or a detail no one’s ever written about before.

If your witches really do practice magic, is their power individual or communal, or some combination of both? Is magic learned or innate? Can you make witchcraft/magic a source of conflict, rather than a crutch that relieves it?

Does your character need to make choices about her “witchiness”—whether it’s to become a witch, to fully use or curtail her own power, or to educate herself about her power? Against or for whom she will use her power? Will she embrace her power right away, or resist it?

These are, of course, just a start to creating fully realized witch characters, but they’re a way to turn the witch into an integral part of your story, rather than a flat stereotype. Give your readers more to think about when you write witches, so that kids who play pretend will argue over who gets to be the witch, rather than relegating her to an offscreen ghost.

Mary Pleiss: Though some might say all the hours Mary Pleiss spent haunting the library and disappearing into book worlds hinted at her future in writing for middle grade and young adult readers, she confesses that at the time she just thought it was a good way to escape her noisy family (she loves them, really, but six siblings can be a bit much at times). She is a curriculum development specialist, teacher, and recent graduate of Vermont College of Fine Arts, with an MFA in Writing for Children and Young Adults.

Mary Pleiss: Though some might say all the hours Mary Pleiss spent haunting the library and disappearing into book worlds hinted at her future in writing for middle grade and young adult readers, she confesses that at the time she just thought it was a good way to escape her noisy family (she loves them, really, but six siblings can be a bit much at times). She is a curriculum development specialist, teacher, and recent graduate of Vermont College of Fine Arts, with an MFA in Writing for Children and Young Adults.

Follow Mary on Twitter: @MKPleiss

This blog post was brought to you as part of the March Dystropian Madness blog series.

By Mary Pleiss

When I was a little girl, the witches I knew came from fairy tales. They were old, ugly, and mean–life ruiners who cast evil spells with no provocation. My young friends and I ran into the problem of the witch in our play. We didn’t want to meet a witch in a dark forest or a bright one, even if that forest was the pair of trees in our backyard. Certainly none of us wanted to be the witch. But we knew we had to have a witch. Witches made things happen, provided scary, shivery tension, and gave the good characters something to fight against and overcome.

When I was a little girl, the witches I knew came from fairy tales. They were old, ugly, and mean–life ruiners who cast evil spells with no provocation. My young friends and I ran into the problem of the witch in our play. We didn’t want to meet a witch in a dark forest or a bright one, even if that forest was the pair of trees in our backyard. Certainly none of us wanted to be the witch. But we knew we had to have a witch. Witches made things happen, provided scary, shivery tension, and gave the good characters something to fight against and overcome.

We often solved this problem by keeping the witch offscreen; we called out plot points detailing the unseen, unheard witch’s actions: “Now the witch is casting her spell. If you get to the swing set, you’re safe!” or, “You stepped into the witch’s clover patch–you’re trapped!” We could imagine the witch without casting her because we’d read stories and seen movies (mostly Disney movies and of course The Wizard of Oz). We knew witches well enough to weave them into our play without having to face the fact that we all had it in ourselves to be witches.

In sixth grade, I read Elizabeth George Speare’s The Witch of Blackbird Pond, and I started thinking about witches in a different way. What made the people of Wethersfield believe Hannah Tupper and Kit Tyler were witches, when any reader could see they weren’t magical or evil–just a little bit different? Why did their neighbors feel the need to banish or imprison them? If Hannah and Kit weren’t really evil, what did that say about the fairy tale witches I’d always feared and hated?

In sixth grade, I read Elizabeth George Speare’s The Witch of Blackbird Pond, and I started thinking about witches in a different way. What made the people of Wethersfield believe Hannah Tupper and Kit Tyler were witches, when any reader could see they weren’t magical or evil–just a little bit different? Why did their neighbors feel the need to banish or imprison them? If Hannah and Kit weren’t really evil, what did that say about the fairy tale witches I’d always feared and hated?

The witches in our fiction today are very different from those in fairy tales, and it turns out that even the Wicked Witch of the West has more complexity than I realized when I was growing up. I knew her from the movie, but reading the books as an adult, and learning more about the history of the Oz books in particular and witches–and those who were accused of witchcraft–in western culture has witches in a new light. L. Frank Baum was heavily influenced by his mother-in-law, Matilda Gage, who was an historian and feminist who promoted influential theories about women who were called witches in history. Baum had those theories in mind when he populated Oz with witches who were more dimensional than what had come before; they had backstories and motivations, and while some of them were evil, just as many were good.

Since Baum, of course, a number of children’s and YA writers have included witches–and women accused of witchcraft–in their stories. Whether bad, good, or somewhere in between, those witches have developed into characters with more depth and complexity than even Baum could have imagined. As societal attitudes about the roles of girls and women have evolved, fictional characterizations of witches have changed, and we can’t get away with taking the problematic witch offscreen or making her a one-dimensional villain. Now, when we write about witches, we work to make them as dimensional as all of our other characters, and our problem becomes the same as that we face with most other characters: how do we bring the witch to life?

Here are some suggestions and questions you can ask yourself if you’re including witchy characters in your fiction:

Consider doing some research into historical witches and witchcraft trials. You might find an angle or a detail no one’s ever written about before.

If your witches really do practice magic, is their power individual or communal, or some combination of both? Is magic learned or innate? Can you make witchcraft/magic a source of conflict, rather than a crutch that relieves it?

Does your character need to make choices about her “witchiness”—whether it’s to become a witch, to fully use or curtail her own power, or to educate herself about her power? Against or for whom she will use her power? Will she embrace her power right away, or resist it?

These are, of course, just a start to creating fully realized witch characters, but they’re a way to turn the witch into an integral part of your story, rather than a flat stereotype. Give your readers more to think about when you write witches, so that kids who play pretend will argue over who gets to be the witch, rather than relegating her to an offscreen ghost.

Mary Pleiss: Though some might say all the hours Mary Pleiss spent haunting the library and disappearing into book worlds hinted at her future in writing for middle grade and young adult readers, she confesses that at the time she just thought it was a good way to escape her noisy family (she loves them, really, but six siblings can be a bit much at times). She is a curriculum development specialist, teacher, and recent graduate of Vermont College of Fine Arts, with an MFA in Writing for Children and Young Adults.

Mary Pleiss: Though some might say all the hours Mary Pleiss spent haunting the library and disappearing into book worlds hinted at her future in writing for middle grade and young adult readers, she confesses that at the time she just thought it was a good way to escape her noisy family (she loves them, really, but six siblings can be a bit much at times). She is a curriculum development specialist, teacher, and recent graduate of Vermont College of Fine Arts, with an MFA in Writing for Children and Young Adults.

Follow Mary on Twitter: @MKPleiss

This blog post was brought to you as part of the March Dystropian Madness blog series.

When I was a little girl, the witches I knew came from fairy tales. They were old, ugly, and mean–life ruiners who cast evil spells with no provocation. My young friends and I ran into the problem of the witch in our play. We didn’t want to meet a witch in a dark forest or a bright one, even if that forest was the pair of trees in our backyard. Certainly none of us wanted to be the witch. But we knew we had to have a witch. Witches made things happen, provided scary, shivery tension, and gave the good characters something to fight against and overcome.

When I was a little girl, the witches I knew came from fairy tales. They were old, ugly, and mean–life ruiners who cast evil spells with no provocation. My young friends and I ran into the problem of the witch in our play. We didn’t want to meet a witch in a dark forest or a bright one, even if that forest was the pair of trees in our backyard. Certainly none of us wanted to be the witch. But we knew we had to have a witch. Witches made things happen, provided scary, shivery tension, and gave the good characters something to fight against and overcome. In sixth grade, I read Elizabeth George Speare’s The Witch of Blackbird Pond, and I started thinking about witches in a different way. What made the people of Wethersfield believe Hannah Tupper and Kit Tyler were witches, when any reader could see they weren’t magical or evil–just a little bit different? Why did their neighbors feel the need to banish or imprison them? If Hannah and Kit weren’t really evil, what did that say about the fairy tale witches I’d always feared and hated?

In sixth grade, I read Elizabeth George Speare’s The Witch of Blackbird Pond, and I started thinking about witches in a different way. What made the people of Wethersfield believe Hannah Tupper and Kit Tyler were witches, when any reader could see they weren’t magical or evil–just a little bit different? Why did their neighbors feel the need to banish or imprison them? If Hannah and Kit weren’t really evil, what did that say about the fairy tale witches I’d always feared and hated? Mary Pleiss: Though some might say all the hours Mary Pleiss spent haunting the library and disappearing into book worlds hinted at her future in writing for middle grade and young adult readers, she confesses that at the time she just thought it was a good way to escape her noisy family (she loves them, really, but six siblings can be a bit much at times). She is a curriculum development specialist, teacher, and recent graduate of Vermont College of Fine Arts, with an MFA in Writing for Children and Young Adults.

Mary Pleiss: Though some might say all the hours Mary Pleiss spent haunting the library and disappearing into book worlds hinted at her future in writing for middle grade and young adult readers, she confesses that at the time she just thought it was a good way to escape her noisy family (she loves them, really, but six siblings can be a bit much at times). She is a curriculum development specialist, teacher, and recent graduate of Vermont College of Fine Arts, with an MFA in Writing for Children and Young Adults.

Reblogged this on Wild About Words and commented:

Mary Pleiss is talking about witches, fairy tales, and stereotyping on Ingrid’s blog. Check it out.

Mary, great post! I just saw the movie Oz, and am wondering on your take on the three witches in that movie. Is this a case of “we’ve come a long way, baby” or “two steps back”?

Hi, L. Marie–I haven’t seen Oz, and to be honest, it’s because the trailer worried me. It looked to me as though they were taking this world whose original creator deliberately created well-rounded female characters with power and agency, and using it to tell a story about them giving up that power to a male outsider who’s supposed to “save” them and find himself in the process–in other words, making a story that had been about women all about the guy. It looked like a step back to me–but as I said, I can’t truly judge until I’ve seen it.

What did you think about it? I’d really love to get some opinions from thoughtful viewers!

Mary, the movie is mostly eye candy. Wonderful colors, dazzling scenery. While I can understand the desire to showcase the wizard’s arrival in Oz, basically your assessment is correct. It also involves women at odds with each other over a man–a definite step back. They act, but their actions are a curdled form of agency. I don’t think you have to make a character weak in order to show another character’s strengths. But imho, the movie shows the witches to be weak to make the “wizard” appear strong.

I haven’t seen the new OZ movie, but I love this discussion. Off to the movie theater…