When Leonard Bernstein first arrived in New York, he was unknown, much like the artists he worked with at the time, who would also gain international recognition. Bernstein Meets Broadway: Collaborative Art in a Time of War looks at the early days of Bernstein’s career during World War II, and is centered around the debut in 1944 of the Broadway musical On the Town and the ballet Fancy Free. This excerpt from the book describes the opening night of Fancy Free.

When the curtain rose on the first production of Fancy Free, the audience at the old Metropolitan Opera House did not hear a pit orchestra, which would have followed a long-established norm in ballet. Rather, a recorded vocal blues wafted from the stage. Those attending must have been caught by surprise, as they were drawn into a contemporary sound world. The song was “Big Stuff,” with music and lyrics by Bernstein. It had been conceived with the African American jazz singer Billie Holiday in mind, even though it ended up being recorded for the production by Bernstein’s sister, Shirley. At that early point in Bernstein’s career, he lacked the cultural and fiscal capital to hire anyone as famous as Holiday. The melody and piano accompaniment for “Big Stuff” contained bent notes and lilting rhythms basic to urban blues, and the lyrics summoned up the blues as an animate force, following a standard rhetorical mode for the genre:

So you cry, “What’s it about, Baby?”

You ask why the blues had to go and pick you.

Talk of going “down to the shore” vaguely referred to the sailors of Fancy Free, as the lyrics became sexually explicit:

So you go down to the shore, kid stuff.

Don’t you know there’s honey in store for you, Big Stuff?

Let’s take a ride in my gravy train;

The door’s open wide,

Come in from out of the rain.

“Big Stuff” spoke to youth in the audience by alluding to contemporary popular culture. It boldly injected an African American commercial idiom into a predominantly white high-art performance sphere, and its raunchiness enhanced the sexual provocations of Fancy Free. “Big Stuff” also blurred distinctions between acoustic and recorded sound. It marked Bernstein as a crossover composer, with the talent to write a pop song and the temerity to unveil it within a high-art context.

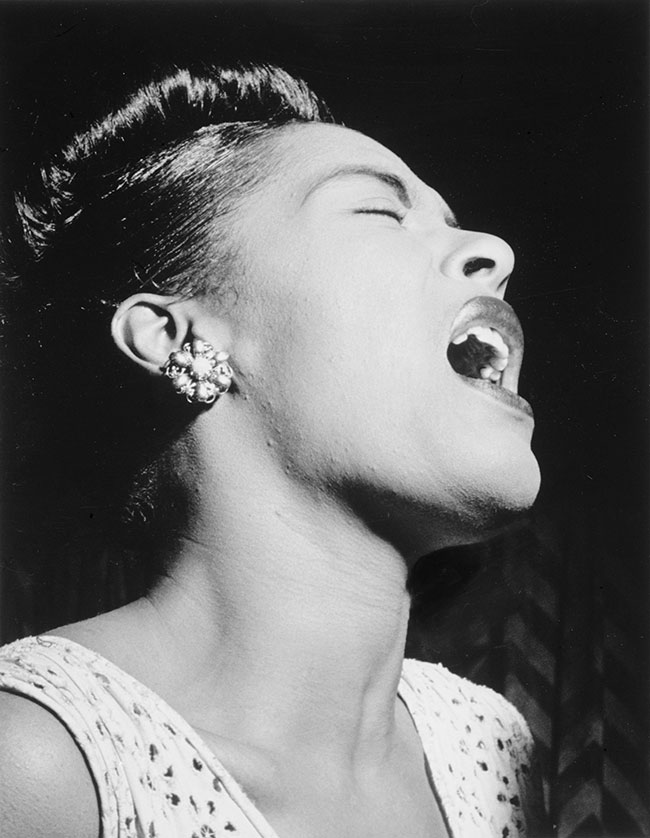

Billie Holiday by William P. Gottlieb, c. February 1947. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

Billie Holiday was “one of [Bernstein’s] idols,” according to Humphrey Burton. He admired her brilliance as a performer, and he was also sympathetic to her progressive politics. In 1939, Holiday first recorded “Strange Fruit,” a song about a lynching that became one of her signatures. With biracial and left-leaning roots, “Strange Fruit” was written by the white teacher and social activist Abel Meeropol. Holiday performed “Strange Fruit” nightly at Café Society, a club that enforced a progressive desegregationist agenda both onstage and in the audience. Those performances marked “the beginning of the civil rights movement,” recalled the famed record producer Ahmet Ertegun (founder of Atlantic Records). Barney Josephson, who ran Café Society, famously declared, “I wanted a club where blacks and whites worked together behind the footlights and sat together out front.”

Bernstein had experience on both sides of Café Society’s footlights. In the early 1940s, he performed there occasionally with The Revuers, and he played excerpts from The Cradle Will Rock in at least one evening session with Marc Blitzstein. Bernstein also hung out at the club with friends, including Judy Tuvim, Betty Comden, and Adolph Green, listening to the jazz pianist Teddy Wilson and boogie-woogie pianists Pete Johnson and Albert Ammons. Thus Bernstein had ample opportunities to witness the intentional “blurring of cultural categories, genres, and ethnic groups” that historian David Stowe has called the “dominant theme” of Café Society.

Robbins also had an affinity for the work of Billie Holiday. In the summer of 1940, he choreographed Holiday’s recording of “Strange Fruit” and performed it with the dancer Anita Alvarez at Camp Tamiment. “Strange Fruit was one of the most dramatic and heart-breaking dances I have ever seen—a masterpiece,” remembered Dorothy Bird, a dancer there that summer.

As a result of these experiences, the music of Billie Holiday had crossed the paths of both Robbins and Bernstein before “Big Stuff” opened their first ballet. While Billie Holiday’s voice was not heard the evening of Fancy Free’s premiere, only seven months passed before she recorded “Big Stuff” with the Toots Camarata Orchestra on November 8, 1944. The fact that Holiday made this recording so soon after the premiere of Fancy Free bore witness to the rapid rise of Bernstein’s clout within the music industry. Over the next two years, Holiday made six more recordings of “Big Stuff,” and when Bernstein issued the first recording of Fancy Free with the Ballet Theatre Orchestra in 1946, Holiday’s rendition of “Big Stuff” opened the disc. Both she and Bernstein recorded for the Decca label. Holiday recorded her final three takes of “Big Stuff” for Decca on March 13, 1946, and that label released Fancy Free the same year.

Musically, “Big Stuff” links closely to the worlds of George Gershwin and Harold Arlen, whose songs drew on African American idioms. Like some of the most beloved songs by these composers — whether Arlen’s “Stormy Weather” of 1933 or Gershwin’s “Summertime” of 1935 from Porgy and Bess – “Big Stuff” used a standard thirty-two-bar song form. With a tempo indication of “slow & blue,” “Big Stuff” has a lilting one-bar riff in the bass, a classic formulation for a jazzbased popular song of the day. The riff retains its shape throughout, as is also typical, while its internal pitch structure shifts in relation to the harmonic motion. Both the accompaniment and melody are drenched with signifiers of the blues, especially with chromatically altered third, fourth, sixth, and seventh scale degrees, and the overall downward motion of the melody is also characteristic of the blues, with a weighted sense of being ultimately earthbound.

Carol J. Oja is William Powell Mason Professor of Music and American Studies at Harvard University. She is author of Bernstein Meets Broadway: Collaborative Art in a Time of War and Making Music Modern: New York in the 1920s (2000), winner of the Irving Lowens Book Award from the Society for American Music.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to onyl music articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

The post Echoes of Billie Holiday in Fancy Free appeared first on OUPblog.