For four centuries Britain was an integral part of the Roman Empire, a political system stretching from Turkey to Portugal and from the Red Sea to the Tyne and beyond. Britain's involvement with Rome started long before its Conquest, and it continued to be a part of the Roman world for some time after the final break with Roman rule. But how much do you know about this important period of British history?

The post How much do you know about Roman Britain? [quiz] appeared first on OUPblog.

The following is extracted from Taken at the Flood: The Roman Conquest of Greece, by Robin Waterfield. This is the story of the Roman conquest of classical Greece – a tale of brutality, determination, and the birth of an empire.

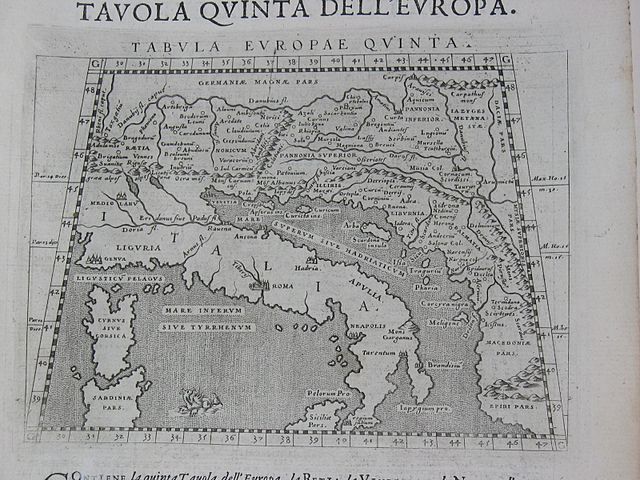

The region known as Illyris (Albania and Dalmatia, in today’s terms) was regarded at the time as a barbarian place, only semi-civilized by contact with its Greek and Macedonian neighbours. It was occupied by a number of different tribes, linked by a common culture and language (a cousin of Thracian). From time to time, one of these tribes gained a degree of dominance over some or most of the rest, but never over all of them at once. Contact with the Greek world had led to a degree of urbanization, especially in the south and along the coast, but the region still essentially consisted of many minor tribal dynasts with networks of loyalty. At the time in question, the Ardiaei were the leading tribe, and in the 230s their king, Agron, had forged a kind of union, the chief plank of which was alliances with other local magnates from central Illyris, such as Demetrius, Greek lord of the wealthy island of Pharos, and Scerdilaidas, chief of the Illyrian Labeatae.

In the late 230s, the Illyrians’ Greek neighbors to the south, the confederacy of Epirote tribes and communities, descended into chaos following the republican overthrow of a by-then hated monarchy. Agron seized the opportunity. Following a significant victory over the Aetolians in 231—they had been hired by Demetrius II of Macedon to relieve the siege of Medion, a town belonging to his allies, the Acarnanians—the Illyrians, confi dent that they could stand up to any of their neighbors, expanded their operations. The next year, they raided as far south as the Peloponnesian coastline, but, more importantly, they seized the northern Epirote town of Phoenice.

The capture of Phoenice, the strongest and wealthiest city in Epirus, and then its successful defense against a determined Epirote attempt at recovery, were morale-boosting victories, but the practical consequences were uppermost in Agron’s mind. Phoenice was not just an excellent lookout point; it was also close to the main north–south route from Illyris into Epirus. More immediately, the town commanded its own fertile (though rather boggy) alluvial valleys, and access to the sea at Onchesmus. There was another harbor not far south, at Buthrotum (modern Butrint, one of the best archaeological sites in Europe), but for a ship traveling north up the coast, Onchesmus was the last good harbor until Oricum, eighty kilometers (fifty miles) further on, a day’s sailing or possibly two. And, even apart from the necessity of havens in bad weather, ancient ships had to be beached frequently, to forage for food and water (warships, especially, had room for little in the way of supplies), to dry out the insides of the ships (no pumps in those days), and to kill the teredo “worm” (a kind of boring mollusk). Phoenice was a valuable prize.

Agron died a short while later, reputedly from pleurisy contracted after the over-enthusiastic celebration of his victories. He was succeeded by his son Pinnes—or rather, by his wife Teuta, who became regent for the boy. Teuta inherited a critical situation. Following the loss of Phoenice, the Epirotes had joined the Aetolian–Achaean alliance, and their new allies dispatched an army north as soon as they could. Th e Illyrian army under Scerdilaidas moved south to confront them, numbering perhaps ten thousand men. The two armies met not far north of Passaron (modern Ioannina).

The fate of the northwest coastline of Greece hung in the balance. But before battle was joined, the Illyrian forces were recalled by Teuta to deal with a rebellion by one of the tribes of her confederacy (we do not know which), who had called in help from the Dardanians. Th e Dardanian tribes occupied the region north of Macedon and northeast of Illyris (modern Kosovo, mainly), and not infrequently carried out cross-border raids in considerable force, with several tribes uniting for a profi table campaign. Scerdilaidas withdrew back north, plundering as he went, and made a deal with the Epirote authorities whereby he kept all the booty from Phoenice and received a handsome ransom for returning the city, relatively undamaged, to the league.

The Dardanian threat evaporated, and in 230 Teuta turned to the island of Issa, a neighbor of Pharos. Th is was a natural extension for her: Issa (modern Vis), along with Corcyra (Corfu) and Pharos (Hvar), was one of the great commercial islands of this coastline, wealthy from its own products, and as a result of convenience of its harbors for the Adriatic trade in timber and other commodities; in fact, at ten hectares, Issa town was the largest Greek settlement in Dalmatia. Teuta already had Pharos and its dependency, Black Corcyra (Korč ula); if she could take Issa and Corcyra, her revenue would be greatly increased and she would become a major player in the region. Teuta put Issa town under siege; in those days, each island generally had only one large town, the main port, and so to take the town was to take the island.

When the campaigning season of 229 arrived, Tueta (who still had Issa under siege) launched a major expedition. Her forces first attacked Epidamnus, a Greek trading city on the Illyrian coast, with an excellent harbor and command of the most important eastward route towards Macedon, the road the Romans began to develop a century later as the Via Egnatia. Th e attack was thwarted by the desperate bravery of the Epidamnians, but the Illyrians sailed off and joined up with the rest of their fleet, which had Corcyra town under siege. The people of Corcyra, Epidamnus, and Apollonia (another Greek colony, eighty kilometers [fifty miles] down the coast from Epidamnus, and certain to be the next target) naturally sought help from the Aetolians and Achaeans, who had already demonstrated their hostility toward the Illyrians, and the Greek allies raised a small fl eet and sent it to relieve Corcyra. But the Illyrians had supplemented their usual fleet of small, fast lemboi with some larger warships loaned by the Acarnanians, who were pleased to thank them for raising the siege of Medion. Battle was joined off Paxoi, and it was another victory for the Illyrians.

In addition to having translated numerous Greek classics, including works by Plato, Aristotle, Herodotus, Xenophon, Polybius, and Plutarch, Robin Waterfield is the author of Why Socrates Died: Dispelling the Myths, Xenophon’s Retreat: Greece, Persia and the End of the Golden Age, Athens: A History, Dividing the Spoils: the War for Alexander the Great’s Empire and Taken at the Flood: The Roman Conquest of Greece. He lives in the far south of Greece on a small olive farm.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only history articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

The post The Illyrian bid for legitimacy appeared first on OUPblog.

By George Garnett

The Norman Conquest of England, recently examined in Rob Bartlett’s television series, offers some striking parallels. The term is jargon, of a type beloved by politicians, because it attempts to foreclose on reflection and debate. The manner of the ‘change’ – by armed force – is veiled, and the agent unspecified, even though both are always obvious. Less obvious is why a particular ‘regime’ requires ‘change’ by foreign military intervention. In the case of Iraq, our own regime has tried and tried again to make the requirement obvious to us, and perhaps also to itself. One such attempt was so ‘sexed up’ that it will go down in history as the ‘dodgy dossier’.

Going back almost a millennium, we find evidence for a similarly sophisticated attempt on the part of a foreign power to justify the replacement of this country’s regime. There are, of course, many differences, in particular Duke William’s claim that he was dutifully suppressing Harold II’s brief, tyrannical usurpation, and, in his own person, restoring the true heir to Edward the Confessor. As such, the official Norman line, embodied in Domesday Book, was that English legitimacy had been restored. Old England continued, and not even under new management. In this respect, the recent forceful change of regime in Iraq was quite different. There, a pretence has been made of imposing a novel and utterly foreign system of government, on the assumption that it is the sole, universally valid type. But in terms of the elaborate efforts made to justify Duke William’s actions, to provide legal cover for endorsement by the eleventh-century equivalent of the UN – the papal curia –, the parallels in tendentious legal scrupulosity are uncanny. We tend to think of medieval rulers, and the clerics who worked and wrote for them, as crude, simple types, unconcerned with diplomatic niceties. Nothing could be further from the truth.

Our distance from 1066 makes it easier to evaluate the results of this particular regime change. The mantra of continuity with Old England, epitomised in a ubiquitous acronym for the status quo in the ‘time’ of King Edward, in turn provided cover for the systematic removal of the English aristocracy, and a transformation in the terms on which their French replacements held their new English lands. This was elite ethnic cleansing. By seizing control of England’s past, the Normans transformed its future, and reconstructed it in their own image – all the while proclaiming that nothing had changed. Harold II was soon airbrushed out of history. By the time Domesday Book was produced, at the end of the Conqueror’s reign, Harold II had never been king. Every major English church had been or was soon to be demolished and rebuilt in the new continental style. Fifty years after the Conquest, England had been rendered almost unrecognisable, and all in the name of a regime change founded on the premise that there had been no change of regime.

Justification and reality were revealingly juxtaposed in York on Christmas Day 1069, on the third anniversary of William’s coronation. In response to English rebellion in the North, he had laid the region waste. Finally, his troops had even torched York Minster. William then arranged for his regalia to be sent up to York, so that he could solemnly display his regality in the burnt out shell of the church. In Iraq thus far the conquest seems to have been much less successful, and therefore the antithesis between the theory and the brutal facts of regime change has not (yet) been as sharply delineated.

George Garnett is Tutorial Fellow in M

Below we have excerpted part of the introduction from the 40th anniversary edition of Robert Conquest’s The Great Terror: A Reassessment. This book, the definitive work on Stalin’s purges, provides an eloquent chronicle of one of humanity’s most tragic events. Robert Conquest is the author of some thirty books of history, biography, poetry, fiction, and criticism. He is a fellow of the Royal Society of Literature, the British Academy, and the American Academy of Art and Sciences. He is at present a research fellow at the Hoover Institution, Stanford University.

Robert Conquest’s The Great Terror: A Reassessment. This book, the definitive work on Stalin’s purges, provides an eloquent chronicle of one of humanity’s most tragic events. Robert Conquest is the author of some thirty books of history, biography, poetry, fiction, and criticism. He is a fellow of the Royal Society of Literature, the British Academy, and the American Academy of Art and Sciences. He is at present a research fellow at the Hoover Institution, Stanford University.

The Great Terror of 1936 to 1938 did not come out of the blue. Like any other historical phenomenon, it had its roots in the past. It would no doubt be misleading to argue that it followed inevitably from the nature of Soviet society and of the Communist Party. It was itself a means of enforcing violent change upon that society and that party. But all the same, it could not have been launched excpet against the extraordinarily idiosyncratic background of Bolshevik rule; and its special characteristics, some of them hardly credible to foreign minds, derive from a specific tradition. The dominating ideas of the Stalin period, the evolution of the oppostionists, the very confession in the great show trials, can hardly be followed without considering not so mch the whole Soviet past as the development of the Party, the consolidation of the dictatorship, the movements of faction, the rise of individuals, and the emergence of extreme economic politics.

After his first stroke on 26 May 1922, Lenin, cut off to a certain degree from the immediacies of political life, contemplated the unexpected defects which had arisen in the revolution he had made.

He had already remarked, to he delegates to the Party’s Xth Congress in March 1921, “We have failed to convince the broad masses.” He had felt obliged to excuse the low quality of many Party members: ‘No profound and popular movement in all history has taken place without its share of filth, without adventurers and rogues, without boastful and noisy elements…A ruling party inevitably attracts careerists.” He had noted that the Soviet State had “many bureaucratic deformities,” speaking of “that same Russian apparatus…borrowed from Tsardom and only just covered with a Soviet veneer.” And just before his stroke he had noted “the prevalence of personal spite and malice” in the committees charged with purging the Party.

Soon after his recovery from this first stroke, he was remarking, “We are living in a sea of ilegality,” and observing, “The Communist kernal lacks general culture”, the culture of the middle classes in Russia was “inconsiderable, wretched, but in any case greater than that of our responsible Communists.” In the autumn he was criticizing carelessness and parasitism, and invented special phrases for the boasts and lies of the Communists: “Com-boasts and Com-lies.”

In his absence, his subordinates were acting more unacceptably than ever. His criticisms had hithero been occasional reservations uttered in the intervals of busy political and governmental activity. Now they became his main preoccupation. He found that Stalin, to whom as General Secretary he had entrusted the Party machine in 1921, was hounding the Party in Georgia. Stalin’s emissary, Ordzhonkidze, had even struck the Georgian Communist leader Kabanidze. Lenin favored a policy of concilation in Georgia, where the population was solidy anti-Bolshevik and had only just lost its independence to a Red Army assault. He took strong issue with Stalin.

It was at this time that he wrote his “Testament.” In it he made it clear that in his view Stalin was, after Trotsky, “the most able” leader of the Central Committee; and he criticized him, not as he did Trotsky (for “too far-reaching self-confidence and a disposition to be too much attracted by the purely administrative side of affairs”), but only for having “concentrated an enormous power in his hands” which he was uncertain Stalin would always know how to use with “sufficient caution.” A few days later, after Stalin had used obscene language and made threats to Lenin’s wife, Krupskaya, in connection with Lenin’s intervention in the Georgian affair, Lenin added a postscript to the Testament recommending Stalin’s removal from the General Secretaryship on the gournds of his rudeness and capriciousness- as being incompatible, however, only with that particular office. On the whole, the reservations made about Trotsky must seem more serious when it comes to politics proper, and his “ability” to be an administrative executant rather more than a potential leader in his own right. It is only fair to add that it was to Trotsky that Lenin turned in support in his last attempts to influence policy; but Trotsky failed to carry out Lenin’s wishes.

The Testament was concerned to avoid a split between Trotsky and Stalin. The solution proposed- an increase in the size of the Central Committee- was futile. In his last articles Lenin went on attack “bureaucratic misrule and willfulness,” spole of the condition of the State machine as “repugnant,” and concluded gloomily, “We lack sufficienct civilization to enable us to pass straight on to Socialism although we have the political requisities.”

“The political requisities…”- but these were precisely the activity of the Party and governmental leadership which he was condemming in practice. Over the past years he had personally launched the system of rule by a centralized Party against- if necessary- all other social forces. He had creaded the Bolsheviks, the new type of party, centralized and discilpline, in the first palce. He had preserved its identity in 1917, when before his arrival from exile the Bolshevik leaders had aligned themselves on a course of conciliation with the rest of the Revolution. There seems little doubt that without him, the Social Democrats would have reunited and would have taken the normal position of such a movement in the State. Instead, he had kept the Bolsheviks intact, and then sought and won sole power- again against much resistance from his own followers…

…In destroying the Deomcratic tendency within the Communist Party, Lenin in effect threw the game to the manipulators of the Party machine. Henceforward, the appartus was to be first the most powerful and later the only force within the Party. The answer to the question “Who will rule Russia?” became simply “Who will win a faction fight confined to a narrow section of the leadership?” Candidates for power had already shown their hands. As Lenin lay in the twilight of the long decline from his last stroke, striving to correct all this, they were already at grips in the first round of the struggle which was to culminate in the Great Purge.

ShareThis