The new school year has started, which means I've officially ended the work I did for a summer research fellowship from the

University of New Hampshire Graduate School, although there are still a few loose ends I hope to finish in the coming days and weeks. I've alluded to that work previously, but since it's mostly finished, I thought it might be useful to chronicle some of it here, in case it is of interest to anyone else. (Parts of this are based on my official report, which is why it's a little formal.)

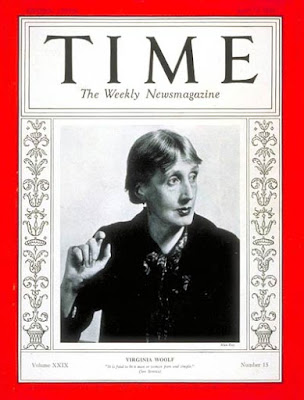

I spent the summer studying the literary context of Virginia Woolf’s writings in the 1930s. The major result of this was that I developed

a spreadsheet to chronicle her reading from 1930-1938 (the period during which she conceived and wrote her novel

The Years and her book-length essay

Three Guineas), a tool which from the beginning I intended to share with other scholars and readers, and

so created with Google Sheets so that it can easily be viewed, updated, downloaded, etc. It's not quite done: I haven't finished adding information from Woolf's letters from 1936-1938, and there's one big chunk of reading notebook information (mostly background material for

Three Guineas) that still needs to be added, but there's a plenty there.

Originally, I expected (and hoped) that I would spend a lot of time working with periodical sources, but within a few weeks this proved both impractical and unnecessary to my overall goals. The major literary review in England during this period was the

Times Literary Supplement (TLS), but working with the TLS historical database proved difficult because there is no way to access whole issues easily, since every article is a separate PDF. If you know what you’re looking for, or can search by title or author, you can find what you need; but if you want to browse through issues, the database is cumbersome and unwieldy. Further, I had not realized the scale of material — the TLS was published weekly, and most reviews were 800-1,000 words, so they were able to publish about 2,000 reviews each year. Just collecting the titles, authors, and reviewers of every review would create a document the length of a hefty novel. The other periodical of particular interest is the

New Statesman & Nation (earlier titled

New Statesman & Athenaeum), which Leonard Woolf had been an editor of, and to which he contributed many reviews and essays. Dartmouth College has a complete set of the

New Statesman in all its forms, but copies are in storage, must be requested days in advance, and cannot leave the library.

All of this work could be done, of course, but I determined that it would not be a good use of my time, because much more could be discovered through Woolf’s diaries, letters, and reading notebooks, supplemented by the diaries, letters, and biographies of other writers. (As well as Luedeking and Edmonds’

bibliography of Leonard Woolf, which includes summaries of all of his

NS&N writings — perfectly adequate for my work.)

And so I began work on the spreadsheet. Though I chronicled all of Woolf’s references to her reading from 1930-1938, my own interest was primarily in what contemporary writers she was reading, and how that reading may have affected her conception and structure of

The Years and, to a lesser extent,

Three Guineas (to a lesser extent because her references in that book itself are more explicit, her purpose clearer). As I began the work, I feared I was on another fruitless path. During the first years of the 1930s, Woolf was reading primarily so as to write the literary essays in

The Common Reader, 2nd Series, which contains little about contemporary writing, and from the essays themselves we know what she was reading.

But then in 1933 I struck gold with this entry from 2 September 1933:

I am reading with extreme greed a book by Vera Britain [sic], called The Testament of Youth. Not that I much like her. A stringy metallic mind, with I suppose, the sort of taste I should dislike in real life. But her story, told in detail, without reserve, of the war, & how she lost lover & brother, & dabbled her hands in entrails, & was forever seeing the dead, & eating scraps, & sitting five on one WC, runs rapidly, vividly across my eyes. A very good book of its sort. The new sort, the hard anguished sort, that the young write; that I could never write. (Diary 4, 177)

Vera Brittain’s Testament of Youth was published in 1933, and was one of the bestselling books of the year. It remains in print, and

a film of it was in US theatres this summer. What struck me in Woolf’s response to it was that she called it a book “I could never write” — and she did so just as

The Years was finding its ultimate form in her mind, and only months before she started to write the sections concerned with World War One. What also struck me was that her response to

Testament of Youth was in some ways similar to her infamous response to Joyce’s

Ulysses, a book she thought vulgar and a bit too obsessed with bodily functions, but which also clearly fascinated and

influenced her.

One of the things that occurred to me after reading Woolf’s note on

Testament of Youth was that

The Years is among her most physically vivid novels. Sarah Crangle

has said of it: “

The Years is a culminating point in Woolf ’s representation of the abject, as she incessantly foregrounds the body and its productions” (9). The September 2 diary entry shows that Woolf was highly aware of this foregrounding in Vera Brittain’s (very popular) book, and her framing of herself as part of an older generation and someone unable to write in such a way may have worked as a kind of challenge to herself.

I then sought out

Testament of Youth and read it (all 650 pages) with Woolf in mind. What qualities of this book caused it to run so rapidly across her eyes? She herself wrote in a letter to her friend Ethel Smyth on September 6: “Vera Brittain has written a book which kept me out of bed till I'd read it. Why?” (

Letters 5, 223). I asked

Why? myself quite a bit as I began reading

Testament, because the first 150 pages or so are not anything a contemporary reader is likely to find gripping. And yet reading with Woolf in mind made it quite clear: The first section of

Testament is all about Vera Brittain’s attempt to get into Oxford, and Woolf herself had been denied (because of her gender) the university education her brothers received, a fact that bothered her throughout her life. The ins and outs of Oxford entrance exams may not be scintillating reading for most people, but for a woman who had never even been able to consider taking those exams, and yet dearly yearned for an educational experience of the sort men were allowed,

Testament provides a vivid vicarious experience. The central part of the book, about Brittain’s experience as a nurse during the war, also provided vicarious experience for Woolf, whose own experience of the war was far less immediate. Woolf lost some friends and distant relations in the war (most notably the poet

Rupert Brooke, with whom she was friendly and may have had some romantic feelings for), but did not experience anything like the trauma that Brittain did: the loss of all of her closest male friends, including her fiancé and her brother. Nor did Woolf see mutilated bodies and corpses, as Brittain did.

Woolf and Brittain were very much aware of each other — Brittain, in fact, makes passing mention to

A Room of One’s Own in

Testament of Youth — and

the first book-length study of Woolf in English was written by Brittain’s great friend

Winifred Holtby (an important character in the latter part of

Testament; after Holtby’s death in 1935, Brittain wrote a biography of her titled

Testament of Friendship, which Woolf thought presented too flat a view of Holtby, a person she seems to have come to respect, though she didn’t much like Holtby’s writing). There is, though, very little scholarship on Woolf, Brittain, and Holtby together, perhaps because Brittain and Holtby seem like such different writers from Woolf in that they were much more committed to a kind of social realism that Woolf abjured. There's a lot of work still remaining to be done on the three writers together. Not only is

Testament of Youth a book that can be brought into conversation with

The Years, but Brittain’s novel

Honourable Estate, published one year before

The Years, has numerous similarities in its scope and goals to

The Years, though it seems almost impossible that it had any direct influence, since it was published when Woolf was doing final revisions of

The Years and she didn’t much like Brittain’s writing, so was unlikely to have read the book (I’ve certainly found no evidence that she did).

In the course of this research, I soon discovered that UNH’s own emerita professor Jean Kennard published a book in 1989 titled

Vera Brittain and Winifred Holtby: A Working Partnership, the first (and still only) scholarly study of the two writers together. I read the book avidly, as I had taken a seminar on Virginia Woolf with Prof. Kennard in the spring of 1998 at UNH as an undergraduate, and I owe much of my love of Woolf to that seminar. The book looks closely at each authors’ writings and proposes that their friendship was a kind of lesbian relationship, an idea that has been somewhat controversial (Deborah Gorham’s

study of Brittain offers a nuanced response).

In addition to exploring the connections and resonances between Woolf, Brittain, and Holtby, I looked at three writers of the younger generation whom Woolf knew personally and paid close attention to:

John Lehmann,

William Plomer, and

Christopher Isherwood. Lehmann worked for the Woolfs at their Hogarth Press in the early thirties, left for a while, then returned and took a more prominent role, buying out Virginia Woolf’s share of the press in the late 1930s. Lehmann and the Woolfs had an often contentious relationship, as he was very interested in the work of younger writers, particularly poets, and Virginia Woolf especially had more mixed feelings about the directions that writers such as

W.H. Auden and

Stephen Spender were going in. Woolf wrote a relatively long letter to Spender on 25 June 1935 about his recent collection of criticism,

The Destructive Element, in which she positions her own aesthetics both in sympathy and tension with Spender’s, particularly Spender’s perspective on

D.H. Lawrence.

Spender’s defense of Lawrence helps explain some of Virginia Woolf’s resistance to the younger writer’s aesthetic. One of the insights that my work this summer provided (at least to me) was the extent to which Woolf thought about, and was bothered by, Lawrence, who died in March 1930. (In 1931, Woolf wrote "Notes on D.H. Lawrence", primarily about

Sons and Lovers.) She had complex feelings about Lawrence’s writing — disgust, frustration, and annoyance mixed with fascination. She often said she hadn’t read much of Lawrence’s work, but from the amount of references she makes to it, and the number of critical studies and memoirs about Lawrence that she read and commented on, I don’t think her protestations of not having read much of Lawrence are quite accurate — she was clearly familiar with all his major novels, and I suspect that in her letters she downplayed this familiarity as a hedge against the strong feelings of correspondents who thought Lawrence to be among the greatest British novelists of the age. Lawrence’s work was very much on Woolf’s mind in the first years of the 1930s, and it therefore seems likely to me that

The Years was also conceived as a kind of response to

The Rainbow and

Women in Love in particular. But that's more hunch than anything, and this is a topic for more study.

John Lehmann introduced Christopher Isherwood to the Woolfs, and encouraged them to publish his second novel,

The Memorial, which they did. In 1935, they also published his first Berlin novel,

Mr. Norris Changes Trains (in the US,

The Last of Mr. Norris), then in 1937 his novella

Sally Bowles and in 1939 the interlinked stories of

Goodbye to Berlin (later to be adapted as the play

I Am a Camera and the musical

Cabaret). Isherwood’s experience of Berlin in the 1930s was of particular interest to the Woolfs, who themselves (with some trepidation, given the fact that Leonard was Jewish) traveled through Germany briefly in 193

5 to see the extent of the spread of Nazism.

William Plomer was a writer the Woolfs published in 1926, and who became close friends with Lehmann, Isherwood, Auden, and Spender. Plomer was born to British parents in South Africa, attended schools in England, then returned to Johannesburg, where he finished college and then worked as a farmhand and then with his family at a trading post in Zulu lands. It was there that he wrote

Turbott Wolfe, based partly on his experience at the trading post and partly on his friendships among painters and artists in Johannesburg. He was only 20 years old when he sent it to the Woolfs, and they printed it soon after

Mrs. Dalloway. Leonard was particularly interested in African politics and anti-imperialism, and the novel’s theme of racial mixing as a solution to the tensions between races in South Africa was iconoclastic and proved controversial. Plomer left South Africa and spent time in Japan, experiences which informed his later novel (also published by the Woolfs)

Sado, a story that included homosexual overtones. (Like Lehmann, Isherwood, Auden, and Spender, Plomer was gay, though less openly and comfortably so than his friends.) Plomer would publish a number of books with the Woolfs, including some well-received volumes of poetry, but eventually moved to publish his fiction and autobiographies with Jonathan Cape, where he was an editorial reader (and convinced Cape to publish the first novel of his friend Ian Fleming,

Casino Royale — a very young Fleming, in fact, had written Plomer a fan letter after

reading Turbott Wolfe, the two became friends when Fleming was a journalist in the 1930s, and eventually Fleming dedicated

Goldfinger to Plomer).

Plomer became a more frequent member of the Woolf’s social circle than any other young writer that I’ve noticed, and Virginia Woolf seems to have felt almost motherly toward him. Aesthetically, he was far less threatening than the other young men of the Auden generation, and though his novels can easily be read through a queer frame, he was more circumspect about the topic than his peers.

As the summer wound down and I continued to work through Woolf’s diaries and letters, I became curious about the place of

Elizabeth Bowen’s work in her life. Woolf and Bowen were friends, and Bowen’s work shows many Woolfian qualities, but Woolf made very few conclusive statements about Bowen’s novels that I have been able to find so far — mostly, she acknowledge Bowen sending her each new novel, and always said she would read it soon, but I have only found definite evidence that she read one,

The House in Paris, which is set soon after World War I and, like

Mrs. Dalloway, takes place over the course of a single day. Like the connections and resonances between Woolf, Brittain, and Holtby, the relationship between the works of Woolf and Bowen seems to be ripe for further study.

But the summer has ended, and my studies must now move toward my Ph.D. qualifying exams, so the British writers of the 1930s, as fascinating as they were, must move now to the background as I widen my view toward everything there is to say and know about modernism, postcolonial studies, and queer studies...

Read the rest of this post

The universe has conspired to turn my research work this summer into mass culture — while I've been toiling away on a fellowship that has me investigating Virginia Woolf's reading in the 1930s and the literary culture of the decade, the mini-series

Life in Squares, about the Bloomsbury group and Woolf's family, played on the BBC and the film

Testament of Youth, based on Vera Brittain's 1933 memoir of her experiences during World War One, played in cinemas.

I've now seen both and have mixed feelings about them, though I enjoyed watching each.

Life in Squares offers some good acting and excellent production design, though it never really adds up to much;

Testament of Youth is powerful and well constructed, even as it falls into some clichés of the WWI movie genre, and it's well worth seeing for its lead performance.

The two productions got me thinking about what we want from biographical movies and tv shows, how we evaluate them, and how they're almost always destined to fail. (Of course, "what we want" is a rhetorical flourish, a bit of fiction that would more accurately be expressed as "what I think, on reflection, that I want, at least now, and what I imagine, which is to say guess, what somebody other than myself might want". For the sake of brevity, I shall continue occasionally to use the phrase "what we want".)

Testament of Youth is easier to discuss in this context, partly because it's a single feature film based (mostly) on one text and not a three-part mini-series depicting the lives of people about whom there are shelves and shelves of books. Though the filmmakers clearly read some of the biographies of Vera Brittain, as well as her diaries, and occasionally incorporate (or at least allude to) some of this material, the structure of the film of

Testament of Youth is pretty much the structure of the book, even though the screenplay takes some massive liberties. (I expect the

1979 mini-series was able to be more faithful, since it had more time, but I haven't gotten around to watching it

on YouTube, which is pretty much the only place it seems still to be available, never having been released on DVD.)

For any 2-hour movie of Brittain's memoir, massive liberties are unavoidable, and overall I think the filmmakers found good choices for ways to streamline an unwieldy text — 650 pages or so, with countless characters who constantly bounce from one locale to another.

I should admit here that I don't much like Brittain's book. Some of the war parts are compelling, and it's certainly important as a historical document, but it seems to me at least twice as long as it needs to be, and Brittain simplified the main characters to such an extent that I find it hard to care about any of them. For instance, when Roland, the great love of her life, dies, it's all supposed to be terribly sad and devastating and I just thought, "Finally! No more of that insipid pining and those godawful letters back and forth and that hideous poetry!" (Which is not to say that I wanted more of the slog of the first 100+ pages of the book with all the details of Oxford University's entrance exams.) Someone could create an abridgement of

Testament of Youth, maybe reducing the book to 150 or 200 pages, and it would be vastly more interesting and compelling, because there really is some excellent material buried amidst it all. Concision was not among Brittain's writerly skills.

I am not the right reader for

Testament of Youth, however. None of us are, really. The book became a bestseller for a number of reasons, but one of them was that readers could fill in its thin parts with their own memories, experiences, and griefs. What the film of

Testament of Youth achieves is to evoke some semblance of the emotion that was, I expect, present in the book for its first readers, most of whom would have had memories of the war years, and many of whom would have suffered similar losses as those described by Brittain — losses both of loved ones and of a certain, more innocent, worldview.

The deaths in the film were, for me at least, far more powerful than the deaths in the book. One reason is the change in medium: the move from the words on a page to actors embodying roles. Deaths in books can be hugely powerful, of course (see

A Little Life for a recent example), but Brittain's ability as a writer was not up to the task, at least in a way that would transfer beyond the experiences of people for whom the First World War was still an event that had defined important portions of their lives. The characters in the film are less idealized than in the book, more human. The screenplay by Juliette Towhidi creates situations, moments, and dialogue that allow the characters to live a bit more than they do in Brittain's narrative, where the characters are more asserted by the writer than dramatized. The acting by the men is generally good, and Taron Egerton is especially effective as Brittain's brother Edward. (Kit Harrington struggles a bit in the role of Roland, but it's a nearly impossible role, since its primary requirement is for the actor to make poetic mooning somehow alluring.) But I think the real reason this film of

Testament of Youth ultimately succeeds at evoking some emotion and making us care about what we watch is that

Alicia Vikander is a truly extraordinary actor. Her portrayal of Brittain manages to convey the important overall arc of the character: from naive, idealistic girl to war-hardened woman shattered not only by the events of the war but also by the deaths of all the men she most loved.

Life in Squares might have been saved by its performances as well, given the talent of the actors in the show, but they never get a chance to do much. Writer Amanda Coe tries hard to give focus to the story she wants to tell, but she was unfortunately undone by the limitations of time — three episodes of not quite an hour in length is simply too little for what Coe and the other filmmakers attempt, and the result is mostly thin and unaffecting. Coe does some great things with the material, but there's just not much for the actors to work with, because the scenes move forward so quickly that there's no chance to build up anything. It's a real waste, unfortunately, because the lead actors in the first two episodes, James Norton (as Duncan Grant) and Phoebe Fox (as Vanessa Bell), capture some of the energy, attraction, and personality of young Bloomsbury in ways I've never seen before. The mise-en-scene is important, too, and marvelously rendered, giving a sense of the physical world through careful attention to the detail of sets, props, and, especially, costumes. But it's a mise-en-scene in service to ... well, not much.

For anyone who doesn't know the intricacies of the personal relationships among the "Bloomsberries",

Life in Squares must be terribly confusing, especially given the choice to have two sets of actors play the main characters: a younger group and an older one, with the older group seen in quick flashbacks in the first two episodes, then dominant in the third, which is set in the 1930s. (The BBC has

a helpful guide to the characters on their website.) With so many people coming and going through the show, and only a handful of characters given more than a few lines, it's difficult even for a knowledgeable viewer to know who is who.

The best decision the show makes is to focus primarily on

Vanessa Bell, a fascinating person who has too often been invisible in the pop culture shadow of her sister, Virginia Woolf, but who was really much more at the core of the Bloomsbury group than either Virginia or Leonard Woolf. Her life also exemplified the ideals and aspirations of the group — she was an artist, had an open marriage to

Clive Bell (with whom she had two children), and had a child with

Duncan Grant, who preferred sex with men but for whom Vanessa was about as close as a person can get to what might be thought of as a soul mate. Their lives included mistakes, prejudices, jealousies, and great grief, but nonetheless seem to me to have been quite beautiful.

The problem

Life in Squares fails to solve is the problem of showing entire lives over a long period of time. This was a problem Virginia Woolf knew well, and tackled again and again in her novels. But the problem of narrative time in a movie is very different from the problem of narrative time in a novel, because cinema's relationship to time is different from that of prose narratives, as lots of filmmakers and film theorists have known (Deleuze's

second Cinema book is subtitled "The Time-Image"). This is one of the big perils of biopics, since they seek to show the progression of a life, and yet cinema is usually at its best when taking a more focused, less expansive view. Some wonderful films have covered entire lives —

Citizen Kane comes to mind, as does

32 Short Films About Glenn Gould — but most history-minded movies that take on such a large expanse end up feeling thin, especially if they try to tell the story in a fairly conventional way, as

Life in Squares does. (For comparison:

The Imitation Game can thrive in its

utterly conventional, audience-pleasing form because its narrative is relentlessly straightforward and the history is simplified to fit the linear movement of the plot and the characters' desires.

Life in Squares doesn't simplify the historical figures or events nearly so much, but it also doesn't find a form that fits what it seeks to depict.)

Actually, the problem for

Life in Squares is that it can't decide quite what approach it wants to take — will it be fragmentary and impressionistic, or will it try to string events together in a more linear structure? Linear becomes impossible because there's just so much material, and thus the show has to skip over all sorts of things, but it still retains an urge for linearity that sinks it. (How much better it would have been to, for instance, show us just three days in the lives of the characters. Or to take a page from

Four Weddings and a Funeral and base it on the weddings of Vanessa, Virginia, and Angelica and the days of the deaths of of Thoby Stephen, Lytton Strachey, Julian Bell, and Virginia. Or base it on particular art works. Or ... well, there are any number of possibilities.) Coe structures the story around the love lives of the characters, but there's too much else that she wants to throw in, and it all ends up a muddle that, sadly, too often domesticates people who, in reality, very much did not want to be domesticated.

What's worse,

Life in Squares ultimately fails to show anything much of what's important about Vanessa Bell, Duncan Grant, and the people around them — their contributions to culture. We see paintings around, we see the artists working now and then, and there are a few brief moments when we hear talk of books (Woolf's first novel,

The Voyage Out, is, if I remember correctly, the only one we actually see, though there's some brief mention of

The Years being a bestseller in the third episode). If not for the significant contributions to art, literature, and politics (hello there

John Maynard Keynes, who gets maybe three lines in the whole show), these would not be especially noteworthy people, nor would there be much historical record of them. But more importantly, it's impossible to think of these people

without their contributions to art, literature, and politics, because they lived for art, literature, and politics. (Well, Vanessa Bell and Duncan Grant were less politically inclined than many of the others, but that's relative — the first biography of Leonard Woolf, for instance, was

a political study.)

Life in Squares does an admirable job of showing the truly radical sexual politics of the group, but it subordinates everything else to the personal relationships, which of course makes for easier drama, even if that drama is, as here, unfulfilling. But what it looks like and feels like and sounds like to devote your life to the things the Bloomsbury Group devoted their life to ... that isn't really here in a meaningful way.

(Is there a movie about a writer that gives a real sense of the writing life? Nothing comes immediately to mind. For artists, yes —

Mr. Turner, Vincent & Theo — but the making of art is itself visual action.

Carrington, which could almost be

Life in Squares Episode 2.5, was better because it focused very closely on its two protagonists and allowed Lytton Strachey to talk to Carrington about books and Carrington to work on, and discuss, her art. It's still pretty flat as a movie, but it's earnest and Jonathan Pryce and Emma Thompson are quite good in their roles.)

Which brings me back to the original question: What do we want from biopics? Why was I excited to see a new film of

Testament of Youth and a mini-series about the Bloomsbury Group? Why, even now, given all I've said especially about

Life in Squares, am I glad these exist?

Partly, there's a sense of validation. It's a powerful feeling when mass culture recognizes the perhaps strange or esoteric thing you yourself obsess over. I watched the first episode of

Life in Squares with a friend who only knows Virginia Woolf's name because he's seen her books around my house. He was bored by the show, but seemed amused by my ability to expound on the various relationships and histories of the characters flitting across the screen (and indistinguishable to him) — and in that moment, suddenly all of the work I've done this summer (not to mention the past twenty years of sometimes casually, sometimes obsessively reading in and around Woolf and her circle) felt somehow less ... hermetic.

This, I could say,

is something the wider world cares about, too, at least a little, at least superficially, at least...

It's possible that

Life in Squares was a more fulfilling experience for me than for most viewers who know less about the characters and era. Not only could I figure out who was who, but I could also fill in the blanks that the show didn't have time or ability to dramatize. In that way, the show was, for me, pointillistic: my mind's eye filled in the space between the dots and extrapolated form from the individual moments of color.

Knowledge of the book of

Testament of Youth is not necessarily helpful for the movie, because the film takes so many (mostly necessary) liberties that it's likely the knowledgeable viewer will become distracted by thinking about where the book and movie diverge. Both

Testament and

Life in Squares suffer from common problems of biopics, particularly name-dropping and random, obligatory cameos. Characters in

Life in Squares constantly have to say each other's names because there are so many of them and they're all so quickly dealt with. Large historical moments must of course be alluded to in dialogue. And then important people must at least show up — there's a pointless moment with

Vita Sackville-West in

Life in Squares, for instance, and the presence of

Winifred Holtby in

Testament of Youth is only explicable because Holtby was so important in Brittain's life; but she gets so little time in the movie that she feels like she's been airdropped in at the last moment, and the portentousness of her announcing herself is never really dealt with. This brings me back, as ever, to the wonder that is

Mr. Turner — director/writer Mike Leigh in that film and in his other historical movie,

Topsy Turvy, avoids this sort of thing, because he knows that a movie is not a history book, and that what matters is not so much who people are as what they do and how they behave with each other.

What do we want to be accurate in our biopics ... and why? Does it matter if three minor characters are melded into one? Does it matter if chronologies are rearranged or simplified? Does it matter if people are put into places where they never were? "Well, it depends..." you say. Depends on what, though? I want to say that it depends on the ultimate goal, the effect, the meaning.

For me, the only changes that feel like betrayals are ones that distort the personality of characters I care about. Both

Testament of Youth and

Life in Squares do pretty well on that count, which is why, for all my grumbling, I was overall able to enjoy them and feel not great animosity toward them. I wish that the makers of each had been more imaginative, certainly —

Life in Squares needed more imagination in order to come alive and feel vital, while

Testament falls into too many clichés of the WWI story (plenty of which are directly from Brittain's text, which is why circumventing them requires significant imagination) and adds a couple of credibility-straining coincidences (particularly with Edward in France). If the Vera Brittain of the movie is a bit less naive and jingoistic at first than the real Vera Brittain was as a girl and the textual Vera Brittain is in the book, there is still a strong sense of her development in the film and, especially, in Vikander's performance, which begins with idealistic energy and ends with something far more profound.

In the end, I suppose what I want from biopics is a sense of the ordinary moments of extraordinary lives and the emotional realities of worlds gone by. This is something that drama in general can give us, and that cinema can give us especially well, with the camera-eye's ability to zoom and focus and linger and look. I got a sense of all that now and then in

Life in Squares, especially when it calmed down and didn't try to squeeze so much in — I got a sense (imaginary, of course, but real in the way only the imaginary can be) of why everybody who ever met him seems to have fallen in love with Duncan Grant, and why Vanessa Bell was such a bedrock of the group, and what, in some way, it maybe felt like to wander those rooms and landscapes when they were not museums but just the places these people lived.

Testament of Youth offers a bit more, and also shows some other virtues of the historical or biographical film — it enlivened the material for me, and I returned to the book with a certain new appreciation, a new ability to find my way into it, to care about it and to imagine how its first readers cared about it.

The cinema fell upon its prey with immense rapacity, and to this moment largely subsists upon the body of its unfortunate victim. But the results are disastrous to both. The alliance is unnatural. Eye and brain are torn asunder ruthlessly as they try vainly to work in couples. The eye says: 'Here is Anna Karenina.' A voluptuous lady in black velvet wearing pearls comes before us. But the brain says: 'That is no more Anna Karenina than it is Queen Victoria.' For the brain knows Anna almost entirely by the inside of her mind -- her charm, her passion, her despair. All the emphasis is laid by the cinema upon her teeth, her pearls, and her velvet. Then 'Anna falls in love with Vronsky' -- that is to say, the lady in black velvet falls into the arms of a gentleman in uniform, and they kiss with enormous succulence, great deliberation, and infinite gesticulation on a sofa in an extremely well-appointed library, while a gardener incidentally mows the lawn. So we lurch and lumber through the most famous novels of the world. So we spell them out in words of one syllable written, too, in the scrawl of an illiterate schoolboy. A kiss is love. A broken cup is jealousy. A grin is happiness. Death is a hearse. None of these things has the least connection with the novel that Tolstoy wrote, and it is only when we give up trying to connect the pictures with the book that we guess from some accidental scene -- like the gardener mowing the lawn -- what the cinema might do if is were left to its own devices.

—Virginia Woolf, "The Cinema", 1926

|

| Vanessa Bell by Duncan Grant |