After reading the reviews on Little House on the Prairie by Laura Ingalls Wilder on Debbie Reese’s blog and the Oyate organization’s website, I thought it was time for me to revisit the book I loved as a child. Would I agree with them that my daughter should not read this book when we study this time period in American history? Should LHOP be removed from library shelves and schools?

Can I put aside my emotional ties to the book and look at it through new eyes? I set about to thoroughly critique and assess every mention of Indians.

I wasn’t sure if I could. I did read this book over and over and over as a child while knowing that one of the branches of my family tree is Native American. I grew up with remorse in my heart for what had happened to the American Indian in the United States. I am still disgusted at what happens to the American Indian now and I have always taught my children that we should, quite simply, be terribly ashamed of what our European ancestors did to the Native American. There is no way out of that truth. So did my reading of Little House on the Prairie influence me as a child to see the American Indian in a negative light? No.

It did influence me to understand that the Ingalls family was wrong for moving onto Osage land. It does bother me enormously that on the Little House in the Prairie historic site website, they present a shameful mistruth that Pa did not know he was moving onto Osage land. He sure did and the book says he did on page 316. The site goes on to say that it was too bad Pa didn’t know the government was going to remove the Indians six months after he left. He could’ve settled the land.

Little House in the Prairie is set in 1868. Pa, Ma, Mary, Laura and Baby Carrie are moving west out of the Big Woods of Wisconsin because Pa wants to move to Indian country where only Indians live. They pile in their covered wagon and head to Kansas.

Why? Pa thinks it is too crowded in the Big Woods, he wants to be around more wild animals, in the West the land is level, there are no trees and the grass grows thick and high - pasture as far as the eye can see and most importantly, there are no settlers. Pa promises Laura that she will see a papoose - a little, brown Indian baby.

The obstacles begin to be thrown in the Ingalls’s path. God letting them know that they were not in His Will, in my opinion.

Pa crosses a creek where he is only guessing it is the ford and he makes Jack swim, even when Laura asks for the dog to be allowed in the wagon. Pa is not so nice. The creek supposedly rises too fast and they are all nearly lost in the rushing water. Jack the brindle bull dog is gone. Pa says, “What we’ll do in a wild country without a good watchdog I don’t know.”

I think Pa was impulsive and thoughtless — serious character deficiencies. He moves his family of girls to American Indians’ land from a place of family and community, he crosses the creek in the wrong spot and tries to explain it away as a sudden rising and he loses the dog. What the heck was he thinking?

But in one of my still favorite scenes, Jack finds the family and Pa almost shoots him, thinking the dog is a wolf. The family is camping where there is no evidence of anyone living there; they are 40 miles from Independence.

Laura describes the prairie as teeming with life. Enormous blue sky and birds galore. Wild animals and wild flowers and such beauty as she can hardly believe. Every breath she takes seems to take in the abundance of the prairie. And I love how Ma made order in the midst of the wild. She washed the bedding and clothing right in the middle of the wagon; the girls are always clean, hair brushed and done, the meals cooked. Ma’s compulsiveness to Pa’s impulsiveness.

Ma answers Laura’s questions about the Indians on pages 46 to 47. She tells the girls the Indians won’t hurt them but that she just doesn’t like them. She doesn’t want to see them. Laura confronts her, why did their family move there then? Ma says she doesn’t know if they’re in Indian country or not and that the government may have already opened the land to settlement, they don’t know. This seems to fluster Ma and she gets back to housework.

Pa has decided to build the cabin near the Verdigris River, according to the Little House website, this is about 13 miles southwest of Independence. Laura finds an old walking trail.

Pa answers Laura that she would only see an Indian if he wanted her to see him. He had seen Indians in New York as a boy and Laura tells us that she knows the Indians are “wild men with red skins.”

Then we find out how tough Ma is. A big log falls on her as she is helping Pa build their cabin. She sprains her ankle, but wants no fuss over her. In Chapter 6, she asks Pa why they haven’t seen any Indians. He doesn’t know, he’s seen their camp sites, maybe they’re on a hunting trip. They joke together that Ma could wash clothes in the creek like the Indian women do and Ma says they could cut a hole in the roof to let smoke out and have a fire on the floor like the Indians do. Yet, Ma cooks outside. Pa and Ma justify their sins against the Indians by assuming an air of superiority over them.

It is difficult to get an accurate reading as to Pa’s real beliefs about the American Indians. His words often seem to contradict his actions. But sometimes, his actions support his words. Did he think that he could just live among the Indians? What was he really running away from back in Wisconsin? What had he promised Ma behind closed doors about life in Indian Territory?

When Pa goes out riding in Chapter 7, he does not take his gun as they have plenty of meat EVEN THOUGH he knows the Indians are nearby and they may be in armed hunting parties. Jack acts anxious while Pa is gone and it does not really worry Ma except that she keeps her eyes open. Pa had met other white settlers, some of whom had only seen Indians. On this trip, Pa finds an ill white family and gets them help. He also encounters a pack of fifty wolves, and the wolves do not attack him. Furthermore, Pa does not shoot any of the wolves after he makes it back home and the wolves have circled the cabin. Pa is an unusual man for his time. Often in literature, wolves are depicted as monster-like animals that attack and kill and must be killed. Who is this Pa really that he would ride around without a gun and not shoot any of those wolves around his cabin?

Pa locks the stable, “Where there are deer, there will be wolves, and where there are horses, there will be horse-thieves.” But the family still hasn’t seen any Indians and the Indian camps in the bluffs are deserted. Ma says Laura yells like an Indian and is getting as brown as one, Mary and Pa also and she doesn’t understand why Laura still wants to see an Indian. Laura is tired of waiting to see them.

Finally, in Chapter 11 we meet the Indians. Pa goes hunting and Jack is chained to the stable. The girls are told not to let him loose. The girls stay by Jack. He growls. Two “naked, wild men” are coming down the Indian trail. They are “tall, thin, fierce-looking”, “brownish-red”, have a “tuft of hair”, their eyes are black and glittering like snake eyes, “terrible men” Laura says. The girls are frightened.

And here we have writing at its finest. One of the most difficult tasks a writer faces is to stay true to the voice of the character. Wilder uses the voice of a six-year-old white girl raised by her parents to view American Indians as dangerous. Would she describe them any other way? They were dangerous if you were somewhere you shouldn’t have been.

And that is the crux of the underlying tone of this book, in my opinion. The Ingalls family knew they were doing something wrong and the entire story is flavored in a dichotomous justification and sense of guilt for that wrong.

The Indians go in the house with Ma and baby Carrie and Laura faces her fears and goes in the house. There is a “horribly bad smell” from the skunk skins they wear on their leather thongs and Wilder gives a detailed description of their appearance. She does overuse “black glittering eyes” but I found over usage with other phrases. Remember she could not click on find on a word processor. Or I should say, her daughter Rose could not.

The Indians eat Ma’s cornbread that she serves them, they take all Pa’s tobacco, but they DO NOT harm the family. This is an important point to make. Throughout the story, the Indians never once harm the white family nor any other white families the Ingalls’ know. Doesn’t this contradict what Ma and Laura had expected? Does it contradict what happens in so many other stories about American Indians written in 1935? I know that Dwight Eisenhower often read pulp Westerns to relax. How did those depict American Indians? Could Laura and Rose have been forward thinking? I would appreciate hearing about any exhaustive reviews of the depiction of Native Americans in literature at the time LHOP was written.

And what about that these Indians did not know enough to prepare the skunk skins correctly? A quote from Laura, “Persons appear to us according to the light we throw upon them from our own mind.” Whether the depictions of two Indians lacking in a particular skill are cast from Laura’s mind or her daughter Rose’s, (as she put the finishing touches on Laura’s narrative) we will never know. The depiction does bring to the reader’s mind the sharp differences between the Native culture and the European culture. The inaccuracy, as it appears, is unfortunate in a book published in 1935. Just fifteen years after women won the right to vote and three decades before the civil rights movement. I could not locate any sources as to whether or not the Osage Indians even wore skunk skins.

An inaccuracy of this magnitude is inexcusable in contemporary children’s literature.

Pa gets very angry with the girls when he finds out they considered loosening Jack. “Bad trouble” would’ve happened “And that’s not all.”

Pa makes a locked cupboard to protect their food stores and then he goes on to save a neighbor from death due to gas poisoning at the bottom of the Ingalls’ water well, despite Ma’s protests, and the risk to his own life. So, Pa is like all of us. Sometimes he commits heroic acts and sometimes, based upon his personal beliefs, he does not.

In the “Indian Camp”, Chapter 14, Pa wonders where the Indians have gone, and he takes the girls to see their camp in the heat of summer. Along the way, he stops Jack from killing rabbits as they have enough meat already. Pa reads the tracks at the camp and the girls collect pretty glass beads. Pa did NOT take his gun.

In chapter 15, Laura meets an African-American man for the first time in her life and she describes all of his differences in as much detail as she did with the Indians. Dr. Tan was on his way to Independence, from doctoring the Osage, when he came upon Pa’s house and finds the family sickened with malaria. Jack begged him to come in. He stays for one and half days until Mrs. Scott, the neighbor comes to care for them.

In the next chapter, the chimney catches fire while Pa is hunting. Laura pulls Mary and Carrie in a rocking chair away from the fire. Looks like they are having a lot of problems living on Osage land. Wilder was a lifelong Christian and relaying the extent of their many problems while living where they shouldn’t have been was a conscious decision. Yes, they face tragedies in the other books, but Laura left the two years out of her books when her little brother died. She chose which problems to relay to the reader.

When Pa goes to town for four days, and this length of travel is consistently relayed throughout (including when they left for good), Mrs. Scott comes to visit with Ma. And while Laura is grateful to Mrs. Scott for nursing her and her family, she obviously doesn’t like her.

Mrs. Scott is a racist bigot. She rails against the Indians. She worries about trouble with them, as she should. The Indians would never do anything with the land except to roam around like wild animals - the land belongs to folks that’ll farm it - despite the treaties - that’s common sense and justice. Mrs. Scott goes on to say, “The only good Indian was a dead Indian.” The thought of them makes her blood run cold and she starts to recall the Minnesota massacre but Ma stops her. The Minnesota massacre occurred in 1862.

Mr. Edwards stops by and warns Ma that Indians are camping in the shelter of the bluffs and he offers to stay overnight in the stable. But, Ma is a toughie and she sends Edwards home. Laura worries about Pa crossing the creek bottoms where the “wild men” are.

It rains during this trip for Pa and on the way home, he must continuously break the frozen mud out of the wagon wheel spokes. The terrible wind slows the horses. Pa comes home though with eight squares of window glass in perfect condition.

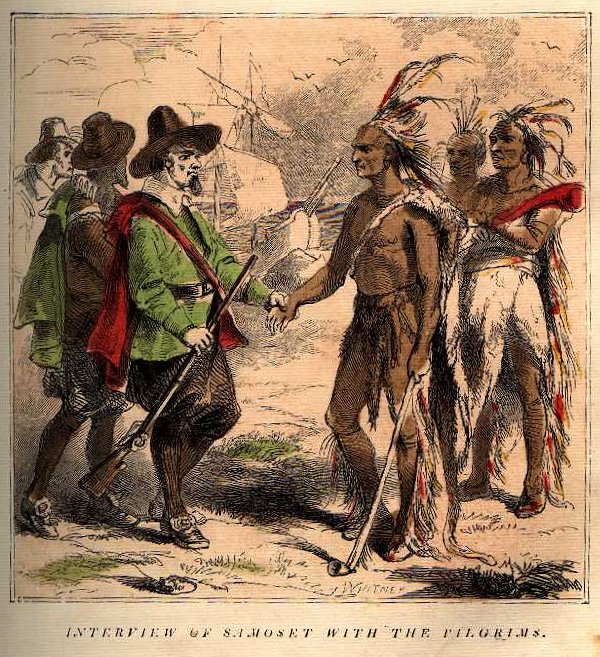

In Chapter 18, “The Tall Indian”, Indians ride by the house on the path — straight and tall, black eyes glittering, “scalplocks wound with colored string”. Pa wouldn’t have built the house so close to a well-traveled road, if he’d known. Another thoughtless mistake. Jack hates Indians and Ma doesn’t blame him, “Indians are getting so thick around here that I can’t look up without seeing one!” she claims. An Indian stands in the doorway and says, “How!” They hadn’t heard him approach. “They couldn’t take their eyes from that Indian. He was so still that the beautiful eagle-feathers in his scalplock didn’t stir. Only his bare chest and the leanness under his ribs moved to his breathing. He wore fringed leather leggings, and his moccasins were covered with beads.” This is the man the story later identifies as Soldat du Chêne, and he is dressed in his culture’s attire.

Pa and the man squat by the fire and Ma serves them dinner. Pa gives him tobacco for his pipe but he cannot understand him. He guesses the Indian is Osage, that he spoke French and he says he was not “common trash”. Ma wishes everyone would keep to themselves and Pa says not to worry, they are friendly. Pa seems to continuously defend them throughout the story.

Months later while Pa is out hunting and trapping, two dirty scowling, mean Indians come to the house, take all the cornbread, the tobacco and Pa’s bundle of furs for trade. One of the Indians makes the other one drop the fur bundle and leave it. Pa says, “All is well that ended well.” Laura asks where the Indians go and her parents tell her that Indians go west because the government makes them. On page 237, Pa says, “When white settlers come into a country, the Indians have to move on. The government is going to move these Indians farther west, any time now. That’s why we’re here, Laura. White people are going to settle this country, and we get the best land because we get here first and take our pick. Now do you understand?” Laura answers yes, but …

I think this story was Laura’s attempts to try and come to that understanding. Why did Pa move them there? Wasn’t it wrong even when all the other white people said it wasn’t? Children are different about assessing right and wrong. It isn’t as easy for them to justify greed and moral injustice. How do we in the 21st century grapple with what our white ancestors did to settle the land we know now as the United States?

Pa has a scary but harmless encounter with a panther. This whole place he has moved them to is dangerous. They almost don’t get any presents from Santa Claus because it is so dangerous - the creek is roaring with rushing water and no one can cross it.

In Chapter 21, “Indian Jamboree”, Pa is gone again for five days taking his fur trade to Independence. The Indians are making a lot of noise, something like an ax chopping, dog barking and a wild and fierce song (but not angry) and it gets louder and louder and faster and it frightens them. Pa returns with goods from town and he tells Ma that the Indians have been complaining to Washington and the white settlers will have to leave Indian territory. But Pa doesn’t believe it; they always make the Indians leave. Even the newspaper says the territory will open soon to settlers. Pa has a very good understanding of the government’s treatment of the American Indian. General William H. Harrison barged his way onto Treaty secured Shawnee land and wiped out the Prophet’s Town in 1811.

In the “Prairie Fire”, Chapter 22, Indians are everywhere now, some friendly, some surly and cross, and the Ingalls give them what they want. Pa and Ma must fight a raging prairie fire with wet sacks and a controlled fire in a furrow. It is a harrowing experience. The fire never reached the Indian camps and Mr. Edwards and Mr. Scott stop by after and raise suspicions the Indians set the fire. Pa doesn’t believe it; the Indians set fires to make the green grass grow and travel easier.

Mr. Edwards doesn’t like all the Indians. Mr. Scott says they’re coming together in the jamboree means “devilment”. “The only good Indian is a dead Indian,” says Mr. Scott. Pa says, “He didn’t know about that. He figured the Indians would be as peaceable as anybody else if let alone. They had moved west so many times that naturally they hated white folks. But an Indian ought to have sense to know when he was licked.” The soldiers at nearby forts will stop any trouble and the Indians are really congregating for the big spring buffalo hunt. Half a dozen tribes who often fought each other were making peace for the hunt. “It’s not likely they’ll start on the warpath against us.”

On page 285, Mr. Scott responded to Pa, “Well, maybe you’re right about it, Ingalls.” He’ll be glad to tell Mrs. Scott what Pa said as she can’t stop thinking about the Minnesota massacre.

Isn’t Pa full of contradictions?

More and more Indians begin to congregate in Chapter 23, “Indian War-Cry”, and the Ingalls hide inside as they hear the “savage” voices shouting. Pa makes a bunch of bullets. Indians stop coming to the house. The prairie feels unsafe, queer, and as if something is watching Laura now. But Laura had already imparted a feeling of danger to us throughout the story. Is everything coming to a head? Laura is afraid of the Indians and Pa spends every waking second with his gun out the window, watching. Pa tells her, “Don’t be afraid” but the warrior yells are worse than wolves howling.

The Osage who spoke French goes galloping by on a black pony during this nightmarish five nights of “wild, fast yipping yells” and days of silence. Ma hopes that the Indians will fight each other. Then, it is over. The Indians split apart and begin to leave. After it is quiet for two nights, Pa takes his gun and scouts along the creek. All the Indians except the Osage have left.

On page 300, Pa meets an Osage in the woods and the Osage tells Pa that all the Indians except the Osage wanted to kill the whites who were on Indian lands. But Soldat du Chêne, the man on the black pony, stopped them. He told the other tribes that the Osage would kill them if they attacked the whites. The other tribes didn’t dare fight the Osage. “That’s one good Indian!” Pa says. He adds that he didn’t believe the only good Indian was a dead one.

Laura invented the character of Soldat du Chêne. He was a contemporary of Tecumseh’s, his portrait done in 1805/1806.

Stephanie Vavra has written a booklet on who really was the Osage Indian that Laura had met:

http://www.amazon.com/Who-Really-Saved-Laura-Ingalls/dp/0971278504

The Indian that stopped the other Indians from attacking and killing white settlers was a good Indian. Much as Tecumseh is credited with stopping massacres of captives in battles the Shawnee won. Tecumseh felt the red men would never grow as a nation of stature if they continued to kill men, women and children captured in war. The people who followed Tecumseh admired and respected this change in approach.

Killing women and children and defenseless men no matter their ethnicity or race or religion is wrong. Even George Armstrong Custer knew this. It is what makes the story of what happened to the native peoples of America so horrific.

In Chapter 24, “Indians Ride Away”, Pa strikes Jack for the first time ever when he growls at Soldat as the Osage passes by the little house on the prairie, dressed the same but wrapped in a blanket. Pa salutes Soldat, the Osage’s face “fierce, still, brown” and “proud”, but Soldat does not acknowledge Pa. “Savage warriors” and “little naked brown Indians” on pretty ponies and all of the people follow Soldat down the trail.

Laura has a “naughty wish” to be an Indian, but “of course she did not really mean it”; she just wanted to be naked, riding on a pony. This uncomfortable scene continues, Laura asks Pa to get her one of those little Indian babies, as if they are objects. Pa reproaches her, but she continues to beg. When Pa tells her the Indian woman wants her baby, Laura cries. Ma says, “Why do you want an Indian baby, of all things!”

But the reader is only left to conjecture what was going on in six-year-old Laura’s mind. My daughter, when younger, sometimes would ask for a baby that she saw. She’d say something like, “Can we get one of those?” Sometimes they were little brown or black or yellow babies and one of her favorite doll babies was an African-American cabbage patch doll. It bothered my racist grandmother enormously when I purchased the doll for my daughter.

On page 311, after many, many Indians went west and they are all gone, Laura writes, “And nothing was left but silence and emptiness. All the world seemed very quiet and lonely.” The family cannot eat and Ma feels “let down”. Pa goes out to plow. Sadness permeates the scene. There is no justification for the white settler’s claims. They got what they wanted but they cannot escape the sin of that greed.

“After the Indians had gone, a great peace had settled on the prairie,” writes Wilder in the next chapter. It seems the family has rectified in their minds what has happened. Everything begins to grow again, it is spring and soon they will live like kings.

And then Mr. Scott and Mr. Edwards pay Pa a visit, bearing disturbing news. On page 316, Pa exclaims, “I’ll not stay here to be taken away by the soldiers like an outlaw! If some blasted politicians in Washington hadn’t sent out word it’d be all right to settle here, I’d never have been three miles over the line into Indian territory.”

And it is for this passage that I believe the book has merit as a supplemental curriculum aid in the study of American history. Somehow, we must explain to our children how this all happened. And Pa explains it in one passage.

Dwight D. Eisenhower writes in his memoir At Ease that one person can change history. That historical events are often an accumulation of small acts done by individuals. Just as the Holocaust could have been prevented if the German citizens, each one on their own, stood up and stopped Hitler, so we can safely say, that Pa’s attitude, and those of Mr. Scott and Mr. Edwards, toward the American Indian, resulted in the Native Americans forced removal from their tribal lands. Each white settler who thought he could plop down on someone else’s land, under the protection of the American government, was guilty. Each white man who voted in Presidents and other leaders who advocated the removal of the American Indian, was guilty.

A good teacher will really explore the entire issue of the Native American’s story using this book. A neglectful teacher will have his/her students read this book and romanticize it.

Pa and Ma and Laura and Mary and Carrie leave their house, with more than they brought, and even the horses are eager to go. Pa tells a captain in Independence about the stranded settlers they saw on their way, ensuring they get help. No one of us is molded incapable of doing both good and evil.

My stories are written from a place of grappling with unanswered questions. I am trying to draw conclusions to issues I’ve faced or issues that disturb me through the working out of the story. I see Wilder attempting this in LHOP, and bringing to it her own opinions, beliefs and feelings.

Maria Tallchief married the great choreographer George Balanchine in 1946 and he developed many roles for her. She also received the Kennedy Center Honors in 1996.

Maria Tallchief married the great choreographer George Balanchine in 1946 and he developed many roles for her. She also received the Kennedy Center Honors in 1996.

May the stories we tell always be a joy and encouragement to those who hear them. God has given us the ability to be creative and reflect His creativity. May we use that to His glory.

Good stuff.

~Luke