new posts in all blogs

Viewing: Blog Posts Tagged with: Charlie Butler, Most Recent at Top [Help]

Results 1 - 20 of 20

How to use this Page

You are viewing the most recent posts tagged with the words: Charlie Butler in the JacketFlap blog reader. What is a tag? Think of a tag as a keyword or category label. Tags can both help you find posts on JacketFlap.com as well as provide an easy way for you to "remember" and classify posts for later recall. Try adding a tag yourself by clicking "Add a tag" below a post's header. Scroll down through the list of Recent Posts in the left column and click on a post title that sounds interesting. You can view all posts from a specific blog by clicking the Blog name in the right column, or you can click a 'More Posts from this Blog' link in any individual post.

Someone whose posts always make me stop and think, Charlie - who now writes and posts as Cathy Butler - clearly gave a lot of us food for thought with this, our fourth most viewed post, on how privilege comes in many forms, and can shape both our writing and our world-views without our realising:

Number 3 will be here at 4.00!

There’s been much talk about e-books lately. Wherever you look, authors are publishing their out-of-print backlists and unplaced books on Kindle and other platforms. Agents and publishers, rowsed from their e-slumber, are trying to catch up, wondering what is a fair percentage for e-book rights - or what they can get away with (which is the same thing, so my free-market friends tell me). According to a powerful post written last month by Kristin Kathryn Rusch, we are witnessing a paradigmatic shift in the way that people think about publishing, and about books themselves. Who needs publishers when the internet lies trembling at our fingertips? In the age of the DIY download, need books ever go out of print again? On the other hand, with no quality control mechanism, some fear that e-literature is destined to be no more than a new recipe for spam.

These aren’t questions I feel qualified to answer, but they were in my mind when I visited Hay-on-Wye with my son the other day. As most UK readers of this blog will know, Hay is a small town on the border of Wales and England, just at the northern tip of the Black Mountains. It is also the home of more than twenty second-hand bookshops, the largest concentration in the UK by far. We were only making a day trip, nothing like long enough to plumb its treasures, but we still made some great discoveries, and it would be a poor soul who could visit Hay without doing so. To be tired of Hay is to be tired of life – or at least of reading.

All the same, when I find a wonderful book that’s been forgotten by all but the cognoscenti (who hug their enthusiasms to their chests like so many racing tips), and especially if that book is going cheap, I feel melancholy as well as triumphant. For Hay is, as well as a great shopping experience, a vast Necropolis. It is a graveyard of out-of-print books – and those of us who stalk its chambers, ripping the jewels from bony necks and fingers, cannot help but feel like tomb raiders – and not in a sexy, Lara Croft kind of way. If we are writers, a trip to Hay is also a plangent reminder of our own mortality, and – perhaps worse! – that of our books. Occasionally I meet one of my own offspring, staring back at me from the dusty shelves like a memento mori. “Buy me!” it seems to beg, in mute appeal. I generally oblige.

We all have our unjustly-forgotten writers, and Hay is a good place to find them. Whatever happened to Nina Beachcroft, for example? Her first three books, Well Met by Witchlight (1972), Cold Christmas and Under the Enchanter (both 1974) are a wonderful debut set, showing mastery of a variety of fantasy genres, from comic supernatural

Occasionally people ask me which aspect of my writing I’m most proud of. Is it the flawless characterization? The wonderfully-observed descriptive passages? The dialogue that tangoes off the page? The plots, as artfully constructed as the Daedalian labyrinth? Or some alchemic combination of all the above?

Oddly enough, the stroke I remember with the greatest pride is one that passes most readers by. It occurs in my first published book, The Darkling. The Darkling was published in 1997 (in the same month as Harry Potter and the Philosopher’s Stone, as I like to remind people with a gloomy starward shaking of the fist), but was written some years earlier, and it was in 1992 that I had to face up to the tricky problem of what to call Jamie’s pet gecko.

Jamie was the younger brother of my heroine and narrator, Petra McCoy. His own part in the story is relatively minor, and that of his pet lizard smaller still, but it needed a name, and I knew that (given Jamie’s character) its name was likely to celebrate a Manchester United leftwinger. But which one? At the time, two young players were making headlines for United in that position, both alike in crossing and scoring power, both given to gecko-ish bursts of furious pace. One was Lee Sharpe, who had made the No. 11 shirt his own during the 1990-91 season, notably by scoring a hat-trick against Arsenal in the League Cup. At 21, Sharpe was a talented player who clearly had a long and illustrious career ahead of him. The other contender was even younger, but his coltish legs were bringing him up fast on the rails. This was the teenaged Ryan Giggs.

The choice mattered, because I wanted (as far as possible) to future-proof my book. Future-proofing is a perennial challenge for children’s writers, who generally try as hard as any Nivea ad to fight the signs of aging. Technology (Dial-up internet? Puhleeze!); clothes (Ray-Bans? Really?); bands and film stars (Kurt Cobain? River Phoenix? You’ve got to be kidding me!); and slang (Could I be any more 1990s?) – all are familiar adversaries. There are several ways around them, more or less effective. For many years children in books could be fitted out in blue jeans in the justified confidence that denim would always be in fashion – or at least not jarringly out. You could invent your own slang or song lyrics. Or you could take the route I did, and bet on longevity.

I almost called that gecko Sharpe instead of Giggs, I really did. Had I had done so, perhaps Lee Sharpe’s career might have prospered. In the event, following this proof of my lack of faith, it went into a fairly precipitous decline, hastened by illness and injury. Sharpe soon moved from Manchester United to Leeds, then on to Bradford, Grimsby an

I’m not especially generous to charity, but I have a few conscience-lubricating direct debits that go off every month to selected causes. Sometimes, mind, I look at my little list and wonder about my priorities. Next to the cancer charity, and the fund to bring clean water to African villages, the longest-standing of these payments – my monthly contribution to the Woodland Trust – may seem rather trivial. After all, keeping a few broadleaf trees alive isn't quite as morally urgent as stopping a child from contracting cholera, is it?

Indeed not – but neither is morality as a zero-sum game, despite the tendentious arguments of policitians (“Wouldn't you rather we closed your local library than stopped homecare for the elderly? Do you hate old people that much?”). That is a false choice, because understanding and valuing what connects us to nature and to our own history is part of what makes us capable of caring about the other things too. Britain is, historically, an island of forests, and although frighteningly little remains of its ancient woodland, a visceral memory and sense of its importance persists amongst even the most urban of town dwellers. The wild wood, as Alan Garner once put it, is "always at the back of our consciousness. It’s in our dreams and nightmares and fairy tales and folk tales."

It's sometimes said that you can judge a country by the way it treats its prisoners. In children's books, woods and trees can act as a similar touchstone. In C. S. Lewis's The Last Battle, for example, we know things have got really bad when the trees are felled on the order of the False Aslan; while Saruman's willingness to cut down trees to feed his furnaces in The Lord of the Rings is a sure sign of his depravity. By contrast, a love of trees betokens health and moral soundness, whether they grow in Milne's Hundred-Acre Wood, a locus amoenus subject to seasons and weather but never to calendars, clocks or the other impedimenta of downtrodden adulthood; or in the hardier worlds created by Arthur Ransome and BB, whose children find both shelter and challenge under the shade of the greenwood, as Robin Hood did before them. Underlying all these, nestling in the leaf litter, lie our memories of the fairy-tale woods with their witches, wolves and wandering children. Their long roots wind in and out of our dreams, as ineluctably as those of Yggdrassil.

When my father died, I paid the Woodland Trust to protect an acre of woodland in perpetuity. Dad’s patch of earth is in a small wood near Winchester, not far (to bring in a gratuitous children’s literature reference) from the grave of Charlotte Yonge. One autumn day, a few months after his death, our family dedicated his acre by scattering his ashes there, in the furze of a small clearing. The ashes blew about a little (‘Don’t sneeze your grandfather!’ I warned my daughter), but I thi

I know from the experience of having written about Acknowledgements elsewhere that most people who read this post are going to disagree with me. So I’ll say it up front: this is just my personal preference, I’m not judging anyone, and I’m happy to contemplate the possibility that I may even be, yes, wrong. Nevertheless, I can’t help clinging to the feeling that I may also be a bit right.

I don’t much care for Acknowledgements pages in novels.

There, I’ve said it.

If I seem a little nervous, it’s because when I mentioned this in another forum some time ago, I was surprised by the visceral ferocity of the reaction. More than one person accused me of wanting to ban the things (which I certainly don’t). Another devoutly hoped that I was joking. Yet another declared my preference “bizarre”. Altogether there was something defensive about the comments I received, as if I were somehow sneering at people who like Acknowledgements.

It’s easy to forget that Acknowledgements pages haven’t always been around, so quickly have they become entr

Immigration is a hot political topic at the moment, both here and in the States. In the wake of

recent immigration laws in Arizona, which many see as legitimizing racial profiling, the image above gained a certain notoriety. It's shocking because Dora the Explorer, the inquisitive Latina created by Nickelodeon, lives in a world that is not only geographically imprecise (is she Mexican? American? South American? Her makers are careful not to say), but blissfully free of violence, or even significant conflict. For all her exploring, Dora will never have to scale a 14-foot metal fence on the north shore of the Rio Grande. To put her face on a mug shot is thus a grimly-effective way of saying, "

This is what 'Homeland Security'

really means." Dora may seem out of place here; but she also reminds us that a good many of the immigrants, refugees and displaced persons in the world are children.

The poster works, in fact, by crossing another kind of border - the border between Dora's safe world and the decidedly dangerous one inhabited by many of her viewers. No one goes to

Dora the Explorer looking for life at its seamiest; for many, indeed, her adventures may offer welcome escape. This isn't, however, to make a case for children as innocents whose minds must never be intruded upon by real-life unpleasantnesses. Children's books have frequently taken on difficult topics - and novels such as Gaye Hicyilmaz's

Smiling for Strangers, to name just one, deal realistically with the hardship and prejudice faced by children who find themselves living as illegal immigrants.

However, the republic of children's literature has many provinces. Elsewhere, particularly in the regions of the fantastic, different rules have tended to apply. Many fantasy stories involve long quests and journeys between different lands and even worlds; but these journeys are seldom conceived in terms of immigration, legal or otherwise. Did Lucy Pevensie obtain a visa to enter Narnia? I'm afraid not, even if her brother Edmund got official permission to send for the rest of the family. ("You let one Son of Adam in, and before you know it they're running the country!") Similarly, Frodo Baggins spent a long time finding ways to sneak into Mordor, a very determined immigrant indeed. The Black Gate would have put even the Department of Homeland Security to shame; but Sauron is unlikely to have seen it in quite those terms.

Closer to our own world, Paddington Bear's adventures often involve minor brushes with officialdom, but on his initial journey from Peru to England an absence of immigration papers doesn't seem to have been a problem. A simple luggage label was sufficient; or perhaps he just gave the immigration officer a Hard Stare? Then again, perhaps Peruvian immigration just wasn't such an issue in 1958. The past, after all, is another country.

4 Comments on Please Look After this Bear - Charlie Butler, last added: 6/29/2010

4 Comments on Please Look After this Bear - Charlie Butler, last added: 6/29/2010

Exhibit A: One of the more annoying adverts I've seen on buses in the Bristol area was paid for by my own university. A few years ago, they tried to attract students with the slogan "Real life starts here!" The implication, I suppose, being that childhood is merely a kind of marking time, a training on the (literal) nursery slopes for real - that is, adult - life.

Exhibit B: an official sign spotted recently affixed to a local lamppost: "Do not feed the seagulls. They annoy people and children."

As a children's writer, what is one to make of it all? That children are but half-formed adults, and childhood meaningful only in so far as it points the way to better things ahead? What could be more calculated to make one march down the street shouting "Children are human beings too!"? This attitude affects children's writers as well, who are notoriously grouchy at being asked when they are going to start writing "real" books - that is, books for real people - that is, for adults.

Prompted by all this, I've been thinking about the ways children's books portray the transition from childhood to adulthood, and I've come up with one of my trademark taxonomies:

1) Avoid it! This subdivides into two categories:

a) The School of Death. From Helen Burns to Leslie Burke, there are heroes and heroines (the latter rather more than the former) who have cheated adulthood by dying before it could get its clammy grey hands on them.

b) Supernatural Solutions. Peter Pan is the obvious example here. But of course, he is a slightly tragic figure, who can stay a child only at the cost of forgetting people and events, and by being excluded for ever from the embrace of a mother. I might mention Pippi Longstocking, too, who at the end of Pippi in the South Seas gives herself, Tommy and Annika a pill that should keep them children for ever. Alas, for jaded adult readers this is clearly a case of whistling to keep her spirits up. The book closes with Pippi blowing out the single candle that sits on the table before her, and we all know what that means.

2) Accept it as a painful necessity.

So, what’s taboo in children’s books these days? Not sex – at least, not to anything like the same extent as it used to be. Bogeys and farts are virtually de rigeur on some shelves of the bookshop. Even death – which, having been a regular feature of Victorian children’s books was hustled from sight when I was growing up, in both books and life – has more recently been treated with full-frontal honesty in children’s books for all ages, from John Burningham’s Granpa and Katherine Paterson’s Bridge to Terabithia to Michael Rosen’s The Sad Book. What’s left? Drugs? Check. Homelessness? Check. War? The Holocaust? Check. Check. Emotional, sexual and physical abuse? Check, check, check. Very little seems to be out of bounds.

What about party politics? They hardly ever appear in children’s books - but maybe it’s because children find them dull rather than because they’re taboo as such? Oliver Postgate famously marked the General Election of October 1974 with an appropriate episode of The Clangers, but I’m not sure it was as thrilling a coup for his young viewers as it was fun for the grown-ups. William Brown once took part in an election too, designating himself a Conservative – but again, more for the amusement of Crompton’s adult readers than William’s own contemporaries. (I don’t remember the name of the story, though – can anyone help?) Budget Tuesdays, when men in suits sat discussing Income Tax and the IMF right where children’s afternoon television ought to have been, were an annual bane of my childhood during the channel-starved 1970s. The idea of having to read about such things too – and for fun! – would have appalled me.

It's not that politics in a wider sense have no place. There are plenty of books for children (both fiction and non-fiction) that deal, and in quite “messagey” ways, with the politics of the environment, or nuclear war, or race relations. They do get read, and few people seem to object to their existence very fiercely – but I suspect that would change should they declare any explicit alignment with a political party. That does appear to be taboo.

I well remember the outrage from parents when one of my primary school teachers – a keen Liberal, whom we will call Mrs H – “accidentally” scattered political leaflets on all our desks in the run up to that same 1974 election. I think she escaped serious trouble (it was a world with fewer disciplinary procedures than now, and more quiet words) but words were definitely said. I’m glad she got away with it, especially as she later taught me to use an air rifle – a source of much innocent pleasure. But for goodness' sake, what possessed you to do such a thing, Mrs H?

MRSA looks like a ball. Bacilli look like a rod. You can tell the difference between them using 100x magnification – the ‘Edu Science Microscope Set’ at Toys’R’Us for £9.99 will do the job very well (if you buy one, with the straightest face in the world, I recommend looking at your sperm: it’s quite a soulful moment).

This passage is taken from Ben Goldacre’s fascinating, important but occasionally smug book, Bad Science (page 282, to be precise). I quote it here merely as the most recent example I happen to have noticed of a widespread phenomenon – the assumption by writers that their readers are, in every way that matters, rather like them. Here, Goldacre is clearly addressing an audience of adult, fertile men – much like Ben Goldacre, in fact, though less well informed about microbiology. Women, children, and vasectomy veterans amongst others will not be in a position to carry out his suggested experiment, and if Goldacre had stopped to think for a moment I like to imagine that he would have realised this, and edited his sentence. However, he didn’t stop – he didn’t have to stop – and neither his editor nor anyone else involved in the book’s production seems to have brought it to his attention. Perhaps they were all men too?

Now let's look at another book. Malorie Blackman’s Noughts and Crosses is set in a world in which white people are considered inferior to blacks. At one point her (white) hero Callum has to put on a sticking plaster. But all the sticking plasters in this world are brown, to match the skin colour of the dominant group. It’s a neat way of bringing to the attention of Blackman’s white readers the fact that, in our own world, the situation is exactly reversed, with plasters coloured pink to match the skins of white people. But how many white people have noticed this

I recently embarked on a two-year adventure that will take me, in Dan Brown style, from end to end of Europe (with a brief foray into Asia) in search of the answer to the age-old question: “What are the differences in the ways that children’s literature is taught to 8-11-year-olds in Spain, the UK, Iceland and Turkey?”

Okay, it’s not quite the Da Vinci code, but it’s still important! It’s easy to become myopically focused on one’s own situation and history, after all. In England and Wales we debate the National Curriculum and Literacy Hour, and complain about literature being taught in snippets rather than whole books. What has happened to reading aloud in class for the sheer pleasure of it, we ask? Where do books fit into the wider curriculum? Are they simply springboards to discussion of “issues”? Are they viewed as ways of inculcating social values – and, if so, whose? Which subjects are out of bounds, and why? Who chooses the books? Why do we read so little in translation? What do the children themselves think about it all?

I and my colleagues will be surveying both teachers and pupils in the four countries to find the answers to some of these questions – and one result, we hope, will be a sharing of ideas that will in a small way help invigorate teaching across the board. So far I’ve only been to Murcia in Spain, but in a couple of weeks I’ll be off to northern Iceland and the University of Akureyri to plan our next move (why didn’t we schedule that trip for midsummer? Why?). Ankara is slated for later in the year.

One difference I noticed right away in Spanish bookshops, by the way, was in the way they display books. Think of the colourful, not to say garish, stands of books in the children’s section of your local Waterstones, with dump bins, covers facing outwards, and each publication striving to be as different from the rest as possible. Then look at the Spanish equivalent, above. The colours of the jackets denote neither publisher nor genre, I’m told, but age-banding - which in this country remains a highly-controversial topic. It all looks very dull to me, but several people have told me that as children they'd have preferred their shelves to have that kind of neat uniformity. So, who's missing a trick, the Spanish or the Brits? Chacun à son goût, I guess.

One of the most exciting things to happen to me as a writer, apart from getting published in the first place, was hearing that my first book had been sold for publication in another country. In fact, The Darkling sold in two, which while hardly spectacular was still very pleasing. In Danish it appeared as Skyggen Masker (which means, I think, “Shadow Masks”). Being a monoglot I can’t comment on how well the translation was done, although a Danish friend of mine claims to have enjoyed the result. Either way, I was not involved in the process at all, and that seems to be fairly typical for translations into foreign languages.

On the other hand, I was involved in translating The Darkling into American English for the US edition – very much so. I was quite surprised how many changes were requested or required by my American publisher. Most of these were minor. Changing “paper round” to “paper route”, for example, caused me few qualms, and there were scores of “translations” into American at that level of inconsequence. But there were trickier issues, too. One central scene was set at a Bonfire Night firework display. Could I change the setting to something more familiar to US children, they asked? Er, not really. Or at least add a few lines to explain Guy Fawkes to a US readership? Oh, okay, then. I added a few lines.

And what about money? Would it be all right to change “50p” to “a dollar”? No, it wouldn’t! But why not, I asked myself? Admittedly, it would be odd for my English heroine to be using American currency, but not that much odder than having her tell her story in American English, surely? I’m not certain I ever sorted this out satisfactorily in my own mind. My rule of thumb, in so far as I had one, was to keep to a minimum those occasions when readers would be forced to notice my word choice, rather than the story that the words were there to tell. I wasn’t very happy about that, though: after all, as a writer I rather like readers to notice my word choices – and to admire them!

I recalled this experience the other day, after hearing from a colleague about the long-running battle in Translation Studies (yes, it is an academic subject) between “domesticators” and “foreignizers”. In brief, domesticating translators are happy to change texts to make them familiar and easily comprehensible to their audience, leaving readers with as little work to do as possible. Publishers of children’s books are domesticators by instinct – as too are Hollywood producers, with their long record of taking books set in Britain and relocating them to California, and the like. Foreignizing translators, by contrast, want their readers to be aware of the alien nature of what they’re reading, and to appreciate it. Part of the pleasure of reading a book from another culture lies precisely in learning about that culture and the ways in which it differs from one’s own, they argue. Publishers, unsurprisingly, tend to consider this a risky commercial strategy, unless the foreignness takes the form of a cliché that is itself familiar. Harry Potter’s Britishness was acceptable, and could even be turned into a selling point, because it played into a set of ideas about Britain that were already current in popular American culture. (On the other hand, some early readers of Harry Potter and the Sorcerer’s Stone were bemused to read that Harry was wearing a jumper – which in US-ese is a sleeveless dress. In later editions I believe this was changed to “sweater”.)

Publishers will perhaps claim that their domesticating approach makes commercial sense, and that readers who relish the alien will always be in a small minority. I’d love to counter that they’re wrong, that they’ve sadly underestimated the curiosity and open-mindedness of US children – but since I have no evidence other than a general-belief-cum-pious-hope that people will be open-minded if their minds haven’t already been glued shut, I can’t say it with absolute conviction.

What I do feel I can grump about unreservedly are those clumsy translations that seem stuck in mid-Atlantic – in which children talk about baseball but deal in pounds and pence, or take a Greyhound bus to Scotland. Such books (no names, no pack-drill) are not authentically foreign, since they depict a place that has never existed, but they’re no more comfortingly domestic than Frankenstein’s monster.

Of course, all this happens in the reverse direction, too – with American books ineptly rendered for the British market. But my impression is that British publishers expect children here to be fairly familiar with American life anyway. And with good reason: on UK television, for example, there are far more television dramas set in American high schools than in British secondary schools. But that’s a rant for another day.

I recently took a fun, online test – one of those things people do when they’re meant to be working – and discovered that I have really bad facial recognition, or, to give it its fancy name, prosopagnosia. Actually, I’ve always known this, but gilding the knowledge with a Greek polysyllable makes it feel much more respectable. Apart from giving me a ready excuse in various embarrassing social settings (“I thought I knew you from somewhere, but then I have so many nieces. It’s the old prosopagnosia playing me up again.”) it explains a difficulty I’ve often had in writing.

In short, I’m just not very good at describing people. I do usually have a sense of whether they’re old or young, tall or short, fat or thin, and will happily say so. I know whether they’re smiling or frowning, and anything that’s directly relevant to the plot I will duly mention. But the acute observation of physical idiosyncrasies, the play of changes across a face, the significance of a hairstyle, none of these comes easily to me. My first-draft descriptions turn into catalogues, blue-tacked onto the action, and it takes a lot of work to integrate them – which usually means, in practice, discarding 90% of what I’d originally written. Maybe that’s not a bad thing: the most effective parts of a book are often written between the lines, after all. However, I still envy people who can (or so it appears) conjure up a person’s history and character through their physiognomy with a few bold Raphaelesque strokes, or hold our attention as they show, à la Sherlock Holmes, how much information can be read in the face, clothes and body language.

Since I’ve got started, let the ABBA records show that I’m equally useless at recognizing flowers (I can do roses, dandelions, buttercups, tulips, daffodils, and er, that’s it) and makes of car (Mini, Robin Reliant and Citroen 2CV are okay, and maybe a Renault Scenic, but that’s only because I drive one). If you found yourself acting as getaway driver for an armed robbery at a florist’s, I would be your ideal witness. Luckily I do know how to look things up in books, though.

Hmm. I don’t seem to have done a great job on selling myself as a writer, today. Perhaps next time I’ll make a list of my good qualities! At least I’ve never been tempted to write a Mary Sue character. I mention that only as a way of pointing you to this fun, online test...

Well, that taught me a lesson. Last weekend I was co-organizing a three-day conference about one of my favourite children’s authors, Diana Wynne Jones. There were 74 people there, from a total of 14 countries. Even for someone with the multitasking skills of a six-armed goddess this would have been a hefty undertaking, and for your poor correspondent it was daunting indeed, though there were considerably more than six capable arms and legs devoted to the conference’s service. I’m glad to say that it went as smoothly as such an undertaking ever can, but by Sunday evening I was pretty pooped.

Then, on Monday morning, my partner and I headed off to another conference in west Wales (this time organized by someone else) where I was to give a paper on the Romans in Britain as represented in children’s books. That was fun too, and included appearances by Michael Cadnum and Caroline Lawrence amongst the assorted scholars. (ABBA's own Lucy Coats would have been there too, but was indisposed - hope you're feeling better, Lucy!). But so much concentrated networking, listening, thinking and socializing have left me a little bleary-brained - and somehow it slipped my mind that I was meant to be posting a blog here on Monday. I totally missed the ABBA birthday party, too! Mea culpa. It was only ever going to be a breathless piece about how hard it is to fit the writing life in with the day-job life, sometimes, but in fact I seemed to have demonstrated that rather than talked about it. So you can think of my post’s non-appearance as a piece of post-modern performance art, right?

Yeah, right. Now, back to the writing pad...

Is it possible to convey the particular essence of a writer’s style – its unique flavour? That’s no easy task, but luckily for reviewers and blurb writers in a hurry, there’s a convenient shortcut, which is to suggest that a book be seen as the literary lovechild of two others. Philip Reeves’ Here Lies Arthur, for example, might be described as “Morte D’Arthur crossed with House of Cards”, while Animal Farm would entice new readers under the banner of “Charlotte’s Web meets The Lord of the Flies!” If you don’t like the idea of these Frankensteinian creations, or are simply squeamish at the thought of beloved classics making the beast with two backs, an alternative is draw on the vocabulary of mind-altering drugs, as in “Coraline is like Alice Through the Looking Glass on speed!”

This way of putting things makes life easier for the reviewer, and can be a service to the reader too, to whom it says, in effect, “You liked Author Y, why not give Author X a go?”

Well, that’s fine, but what does it say about the writers themselves? Writers tend to be ambivalent about the whole notion of influence. Of course, all writers have influences, and most will admit to them. I was delighted when reviewers said that some of my books were reminiscent of Alan Garner. Garner was (and is) a hero of mine, and someone whose influence on me has been palpable. What better model could one take? At the same time, I didn’t want to be seen as just an Alan Garner knock-off. I wanted to be recognized for my own voice. So my pleasure in such acts of recognition was never entirely free of chin-jutting rebelliousness. This quasi-Oedipal anxiety is of course exactly what Harold Bloom’s classic, The Anxiety of Influence, is all about.

Besides, we live in an age that fetishizes originality and novelty. Nothing could be more complimentary than to be described as a “A unique talent”, “A fresh voice”, or “A writer who shows as little respect for convention as a hyperactive toddler at a society wedding.” In that sense, to be compared to anyone is a little galling. Thus, J. K. Rowling (remember her?) caused some irritation with her refusal to admit that her work was steeped in the tropes of children’s fantasy literature, presumably because she feared that to do so would diminish her achievement. In fact, much of her work only makes sense in the context of those tropes.

What would I recommend to the hapless blurb writer, torn between praising a book in terms of other books and praising it for being one-of-a-kind? If I had to pick a cliché, I think I would go for “In the tradition of...” It’s a phrase that settles the matter equitably, paying due regard to the fact that writing comes from somewhere, without closing off the possibility that it may be going somewhere else. So, blurb writers of the future, remember the phrase: “This is a highly original book in the general tradition of Alan Garner.”

Alternatively, just go with “The Bible crossed with Shakespeare... on speed!”

One of the most interesting innovations within children’s literature in Britain in the last decade has been the introduction of the post of Children’s Laureate. The idea, I understand, was hatched in a conversation between Michael Morpurgo and Ted Hughes, then Poet Laureate (and a fine children’s writer to boot). The role of the Poet Laureate, who is appointed by the monarch, goes back a little further, to the reign of Charles II and John Dryden – or possibly Charles I and Ben Jonson, depending how you count it. Jonson, typically, arranged to be paid with a butt of sherry (that’s 700 bottles!), and this tradition continues today. No such luck for the Children’s Laureate – though there’s a useful cheque that goes with the job. And – well, at least the Children’s Laureate isn’t required to praise the efforts of the latest member of the royal family who thinks that writing a picture book is Easy, or to write mellifluous verses on the occasion of some blue-blooded sprog’s first day at school. Humility has its advantages.

The Children’s Laureate post rotates biennially, and there have been five so far: Quentin Blake (1999-2001), Anne Fine (2001-2003), Michael Morpurgo (2003-2005), Jacqueline Wilson (2005-7) and Michael Rosen (2007-2009). I think that represents a pretty good mix of genres and age ranges, though they’ve each approached the job quite differently. But what is that job? Mostly, I think, to keep the profile of children’s books as high as possible, in a world where they’re often neglected or seen as something ‘less’ than books for adults, where the National Curriculum has led to a culture of teaching snippets rather than whole books, where libraries are a soft target in any round of spending cuts, and where children face a range of alternative digital allurements. That sounds very negative, but it’s not all a rearguard action. The Laureate should also be a positive example of what it means to be a children’s writer, and all the holders so far have a great track record of producing books that are both popular with children and highly respected by their peers. Ambassadorship, campaigning and getting your views across are all important, but personally I hope that whoever gets the job this time round won’t stop writing for the duration.

Why am I writing about this? No, no – I’m not on the shortlist, don’t worry! But I do have the honour of being one of the panel that will choose the next Laureate, from a shortlist supplied by children and adults across the country. Right now I’m reading furiously (and delightedly), and in due course I’ll be travelling to a Secret Location for the meeting. I believe the announcement won’t be made officially until June, so there will be a period of bursting-to-say ahead of me, for we panellists have sworn an oath of secrecy. For the one who gabs, the Big Red Scissor Man awaits.

Wish me luck, ABBA readers!

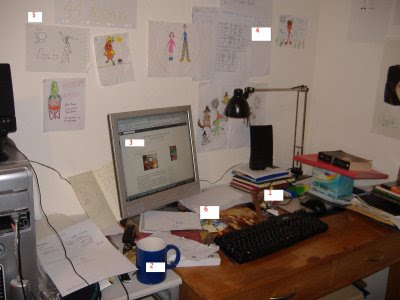

That Adele Geras! Yesterday she uploaded a wonderfully tidy desk picture, and I felt jealous (I suspect I'm not the only one), and ashamed of the depths of disorder to which my own desk - and, by extension, I - had fallen. If the desktop is the window of the soul, then mine is located somewhere round about Dante's fifth circle, and falling.

By way of catharsis - or self-flagellation - let me offer you this alternative vision, taken the minute I'd read Adele's post. Here are some of the features of interest:

1) My pearwood recorder. Like the second Doctor Who, I find playing the recorder a very useful aid to thought. My trusty descant seldom leaves my desk, unless to dance round the room with me in an ungainly pas de deux. Some of my best ideas have come to me as I tooted out a bit of Dowland.

2) The coffee cup. Of course there's always a coffee cup...

3) Reading the Awfully Big Blog Adventure is a terrible displacement activity. Actually, has anyone ever done a book of Displacement Activities? Surely a publisher might be interested - and writers are world's experts on the subject. I could edit an anthology, perhaps, and call it Thieves of Time. Hmm, perhaps I'll spend half an hour making a list of things to go in it...

*half an hour later*

4) This is the timetable for my

day job, which tells me what I should be teaching, week by week. (What, you didn't think I financed my millionaire lifestyle just by writing for children, did you?)

5) Children's art - which doesn't get replaced as often as it ought. I see that some of these were written for my 44th birthday, which was... a while ago, now. Unfortunately I can't have a desk by a window, or the procrastination would never stop. I could happily pass a day watching raindrops nudge each other down the pane.

6) I've been consulting an atlas of modern history - which, in this context, means after 1483. I've only just realized, having read a little about the Kingdom of Naples, why half the people in The Tempest have Spanish names, despite coming from Italy. Am I the only one ever to have wondered about that? If not, am I the only one to wonder for approximately thirty years before bothering to look it up? Now that's procrastination!

What you don't see here, of course, is space for a longhand notebook. That's because I write my first drafts in cafes, on sofas, and in really comfortable chairs, not at the desk. So really this isn't a writing desk after all, just the plain vanilla variety. I'm very fond of it, though. It says nothing very good about me or the unhealthy chaos of my brain, but hey - this thing of darkness I acknowledge mine.

When I was at school, one of my favourite fantasies was that of being a telepath. I loved being able to carry on secret conversations in my head during school lessons, while seeming to have my nose in a maths book. And, since nothing is lonelier than being the only telepath in the world, I created a group of people to be telepathic with – inspired no doubt by stories where this really happened, such as John Wyndham’s The Chrysalids and ITV’s The Tomorrow People.

Being able to speak with other people effortlessly across great distances was appealing in itself, but the fact that it was a secret and exclusive ability was just as important. This was brought home to me a few months ago, when I was watching a DVD of The Tomorrow People. In one scene, a Tomorrow Person was exploring the enemy hideout, but was simultaneously in telepathic contact with his friends back in TP headquarters. Watching this, it suddenly hit me that what had been a magical skill in the 1970s had now been rendered commonplace and dull – because, well, everyone has a mobile, don’t they? And what is telepathy but a swish hands-free mobile with unlimited credit? I could barely watch it after that.

But why? What led to my disenchantment? A few explanations occur to me.

Simple snobbery. As hinted above, it may be that magic keeps its allure only when it’s the preserve of the few – and when it’s a secret. It seems to be standard practice that children in books who discover they have supernatural powers will decide that it's necessary to keep it from the mugg– er, ordinary people. Sometimes the excuses they give for doing so are flimsy in the extreme. Do they really believe they would be a) experimented on by the government or b) put on display in a travelling circus, if people discovered their precious ability to turn into shrews, or make balsa wood taste of cheese? Not for a minute: they just want to be in a Sekrit Club.

Habituation. I still feel a thrill every time I take off in an aeroplane, and can’t understand people who profess themselves bored at the prospect of living out one of mankind's most ancient dreams. But apparently it does happen. Maybe I’m more vulnerable to this in the area of mobile technology?

The puncturing of the mystery. I'm no techie, but if I put my mind to it I could probably get quite close to understanding how mobile phones work. Does knowing that there’s a scientific explanation detract from the glamour? Shouldn’t it rather add to it – being evidence that even the most commonplace things, like gravity and electrons, can add up to something pretty darned marvellous?

I don’t know how far any of these explanations really hit the mark; but another of my regular daydreams is quite useful here. In this one I imagine what would happen should I be plonked down in, say, Restoration London. These daydreams usually start off quite well, with people being amazed and impressed by my tales of computers, televisions and the like, and Oohing at the luminous hands on my wristwatch. However, I soon find that I’m quite unable to explain how any of these inventions actually work. I usually end up testifying to a committee of the Royal Society and making a pretty poor fist of it: “Er, well, there’s this stuff called electricity, see, and it flows down the wire – no, Sir Christopher, not like water down a pipe, more like – well, anyway, it comes out as pictures...”

Robert Hooke in particular is not impressed.

It’s much more satisfactory to have someone from the past – Shakespeare, perhaps, or Isaac Newton – find themselves stuck in my present, and to act as a tour guide. That way I can bask in the reflected glory of several centuries of technological innovation. Not only that, by being seen through their eyes it even regains something of the lustre lost through familiarity. You should see Newton’s reaction (equal and opposite) to the sensation of taking off in a Ryanair flight to Dublin! Best of all, if he comes at me with one of those awkward questions about how exactly jet engines are put together, I have my answer ready and waiting.

“Google it, Sir Isaac,” I tell him loftily. “Just google it.”

In my last post I wrote about some literary coincidences. However, I forgot to mention the strangest one that ever happened to me – an omission I intend to make good now. There is no moral to this story, but it still makes me blink whenever I think what the chances are of this happening.

After my father Thomas died a few years I started going through his papers: writers are nosy like that. Amongst them was a small book, Nearly a Hundred Years Ago, written by his great aunt, Annie Robina Butler. Annie Robina was a children’s writer, and founder of the Children’s Medical Mission, with many titles such as Little Kathleen, or Sunny Memories of a Child-Worker (1890) to her name. This book, though, was a privately printed memoir of her own father, also Thomas, who at the time she wrote it in 1907 had just died, in his nineties. As a young man Thomas had lived at 6 Cheyne Walk in Chelsea, where his father and grandfather had run a classical school (Isambard Kingdom Brunel had been amongst the pupils). That was where Annie had spent her childhood too, until the age of 13, and her book had plentiful details of what it was like to grow up in the house’s lofty, oak-panelled splendour in the 1840s and '50s.

Annie Robina’s book was a fascinating find for me, of course, full of family information, paintings and photographs, and strange excursions. But the truly weird part of this story comes a few weeks later. I was at a lunch for Scattered Authors, and found myself sitting next to Linda Newbery. We chatted, and she told me about a set of books she was writing with Adele Geras and Ann Turnbull, known as the Historical House series. All the stories were to be set in the same London house at different periods of history – each with a young girl as the main character. “Where exactly in London is the house going to be?” I asked her. She told me it was to be in Chelsea, and that although they’d made up a street name, Chelsea Walk, it was very firmly based on Cheyne Walk. The hairs on my neck started to prickle. “Do you happen to remember the house number?”

Of course, it was number 6 – the same house my family had occupied from around 1783 to 1854, and which Annie Robina had described in the memoir I’d just read.

What are the chances?

Naturally I wanted to know if any of the Historical House books were set at the time my family had lived there. I got pretty close: Adele Geras’s Lizzie’s Wish was set in 1857, just three years after the Butlers had left. (In real life, Thomas Butler had sold the house to the Chapel Royal Choir School.) Lizzie’s Wish is an engaging story, which tells of young Lizzie Frazer’s time in the rather grand and formal house of her London relatives, where she offsets loneliness by nursing a wish to plant a walnut tree from her country home. Lizzie and Annie Robina would, in fact, have been almost the same age.

It was fascinating, laying the childhoods of the fictional Lizzie and the real-life Annie side by side. Their lives were very different, even if they lived in the same house at more or less the same time. In the fictional 1850s lonely Lizzie longs to stand on the Chelsea Embankment and watch the shipping. In Annie’s real-life childhood there was no Embankment yet. When the Thames flooded, as it occasionally did, she and the other children reacted with “extreme delight”, and “ran on improvised bridges and sailed their paper boats down the long passages, and fancied themselves in Venice.” (“But Annie Robina,” I cry, “the Thames in your period is a running sewer! Have you no fear of the cholera?” Alas, the miasma theory of cholera transmission is still in vogue, and no one is listening.) In the fictional 6 Chelsea Walk, the ambition of one of Lizzie’s cousins to become a nurse á la Florence Nightingale is at first squished by her class-conscious grandmother. In the real 6 Cheyne Walk Annie’s sister became a medical missionary, dying in Kashmir, and was regarded by her family virtually as a martyr. In the fictional 1850s, Lizzie’s longing to plant her tree is discouraged by her snobbish cousin, who says that London people prefer their flowers in paintings, samplers and vases. In reality, when the classical school failed in the 1820s Thomas Butler and his brother turned the school playground into a lush garden, which was the delight of Annie’s generation. The soil was poor, she admits, and she spent much of her time digging up bricks from the demolished baths of Dr Dominicetti, a hydropath who’d owned the house in the eighteenth century;* but she’s as lyrical as any fictional heroine when she remembers the “hedges of cabbage roses and thicket of many-tinted lilacs”, the wallflower that “sowed itself in the mellow brickwork boundaries, and stonecrop that ran over the wall”, the “jessamine, southernwood, and lavender that breathed their sweetness through the walks.” Immense sunflowers and peonies, double dahlias, Aaron’s rod, giant rhubarb and cat’s head apple trees were amongst the other treasures there.

In general, and with the significant exception of religion (but that’s another story), Victorian reality seems to have been a good deal more unbuttoned and informal, and altogether less – how shall I put it? - Victorian than Victorian fiction, at least in this case. Perhaps there is a moral there, after all?

But – 6 Cheyne Walk, 6 Chelsea Walk. Mirror worlds of fact and fiction. I ask again – what are the chances?

* Dr Dominicetti was scoffed at by Samuel Johnson, but I think he was ahead of his time. How much would you pay for a weekend at a place like this today? “On the right side of the garden, and communicating with the house, was erected an elegant brick building, a hundred feet long, and sixteen wide; in which were the baths and fumigating stones; adjoining to which were four sweating bed-chambers, to be directed to any degree of heat, and the water of the bath, and vaporous effluvia of the stove impregnated with such herbs and plants as might be most efficacious to the case.” An Historical and Topographical Description of Chelsea and Its Environs, Thomas Faulkner, 1810.

As all maths geeks know, the world is divided into 10 kinds of people... those who understand binary code, and those who don’t. As a matter of fact, human beings love dividing things into groups. We’re a classifying species: homo taxonomicus – all librarians at heart. When it comes to books, there are of course many ways to divvy them up beyond the Dewey Decimal System, and sometimes it’s fun to see where one’s own preferences lie. Happy endings versus sad? Realism versus fantasy? Contemporary versus historical? Long versus short? First versus third person narration?

Now, what about convex versus concave books? Not come across that distinction? That’s because I just made it up - but I'd love to know what you think. The way I see it, a concave book is one that reflects light onto itself. It’s a book that takes a particular setting, containing a limited number of people, and explores them thoroughly. It may choose to disrupt this group, perhaps by the device of a Stranger Coming to Town, but the book is all about looking deeper, finding out more, seeing how surface appearances may be deceptive. Concave books thrive in almost all genres. Emma is a concave book. So are Shane, Lord of the Flies, Animal Farm, The Midwich Cuckoos and Murder on the Orient Express. Villages, islands, ships, and other isolated locales are the classic concave settings, and once the plot arrives there it tends not to leave. Concave plots also lend themselves to metaphorical or even allegorical meanings (as with Golding and Orwell). The village is the world writ small.

Convex books, by contrast, reach beyond themselves, reflecting light outwards. Books involving journeys, quests, world-shaking historical events, books conveying a sense of the bustling, multi-faceted nature of life, books that scintillate off to the horizon, are convex books. Great Expectations; War and Peace; The Odyssey; Bonfire of the Vanities; Tom Jones all qualify. They imply the world metonymically (if you like figures of speech).

Some of my favourite books appear in both lists. Thinking it over, however, I realise that all my own books have been concave, to a greater or lesser degree. Perhaps that’s just the way my mind works – although I’d love to think I could write a good convex book too, if I really tried. Can I train myself to do it? I’ve had a book in my head and in notebooks for years now – a convex book, too – which just hasn’t managed to get written, and I’m worried it's because of my ingrained concavity. As to where that comes from, my partner has suggested that a writer’s own life experience may be a factor. If you grow up in a city, you catch glimpses of a hundred new faces every time you walk down the street, and (if you’re that kind of writer) you may wonder about all the stories those faces suggest, stories that weave in and out of each other and off to the edge of the page. If, like me, you grow up in a small town, you see the same faces over and over again – and you wonder what’s going on behind the apparent sameness. The city impresses with its razzle and dazzle; but for us concavers inspiration is more likely to come from a twitching curtain suddenly let fall.

By: Rebecca,

on 2/26/2008

Blog:

OUPblog

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

ben,

A-Featured,

Ben's Place of the Week,

dirt,

haiti,

sisal,

foodstuff,

oupblog,

Geography,

“authentic”,

tofu,

hinche,

trucked,

keene,

Serial Blogging,

maps,

Add a tag

Hinche, Haiti

Coordinates: 19 9 N 72 1 W

Population: 23,599 (2003 est.)

People travel for many reasons, but a chance to sample local or “authentic” cuisine often weighs heavily in the decision-making process. In my own peregrinations I’ve sampled stir-fried insects in Thailand, whale carpaccio in Norway, and stink tofu in Taiwan: all things that are harder to come by in the U. S. of A. An uncommon foodstuff that I haven’t tried however, can be purchased for next to nothing in the impoverished Caribbean nation of Haiti. (more…)

Share This

Someone whose posts always make me stop and think, Charlie - who now writes and posts as Cathy Butler - clearly gave a lot of us food for thought with this, our fourth most viewed post, on how privilege comes in many forms, and can shape both our writing and our world-views without our realising:

Someone whose posts always make me stop and think, Charlie - who now writes and posts as Cathy Butler - clearly gave a lot of us food for thought with this, our fourth most viewed post, on how privilege comes in many forms, and can shape both our writing and our world-views without our realising:

Best trekking agency in nepal

www.nepalholidaystrek.com