By Elijah Siegler

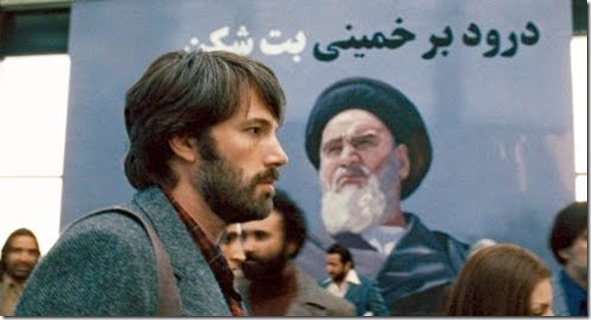

Last night at the Oscars, the Academy awarded a golden statuette to a film about a flawed hero who we the audience empathize with, who departs their normal life, enters a strange world, but returns triumphantly. Did I just describe Best Picture Winner Argo?

Yes, but also best animated short winner, Paperman, best animated feature winner, Brave, and best live action short winner, Curfew.

So whether the hero is a CIA operative, an besotted office worker, an Scottish princess or a suicidal man, and whether the journey is to revolutionary Iran, to a world of sentient paper airplanes, to a dark forest, or to a magical bowling alley, these films, and it’s safe to say, most of their fellow nominees, have spiritually uplifting themes, and generally follow a pattern of a mythic journey to redemption. (Indeed as my colleague’s S. Brent Plate pointed out, religion permeates all nine best picture nominees and the ceremonies themselves.)

Academy members, and audiences in general, like and expect movies to be heroic journeys of redemption. One 2012 film, Cosmopolis, is about a journey that’s anything but heroic and redemptive. Indeed, the film, based on a short novel by Don DeLillo, charts a billionaire’s limo ride across Manhattan to get a haircut as ironic, pointless and even destructive. Unsurprisingly, Cosmopolis received precisely zero Oscar nominations. Now, I’m not here to argue that this film was better than any of the nine nominated films.

One reason that the film’s director and screenwriter, David Cronenberg, despite being widely regarded as one of the world’s best living filmmakers, has never been nominated for, let alone won, an Academy Award, is because all his films explicitly reject themes of “redemption” and “spiritual uplift.”

Cronenberg is known not only an originator of the body horror subgenre (Shivers, Rabid, The Brood), and for adapting difficult works of literature (Naked Lunch, Crash, Cosmopolis), but for being one of the few filmmakers who explicitly identifies as atheist, and whose work ignores all religious themes. Cronenberg’s public atheism is all the more notable considering his association with horror, a genre often analyzed as fundamentally religious. Think about all the horror films that include one of more of the following: the dead displaced, satanic cults, covens, possession, exorcism, ghosts, and curses. Or think how often religious symbols a church or a crucifix, become sites of terror. So it is significant that none of Cronenberg’s films have any religious or supernatural elements. And this is not coincidence, but his conscious choice. More succinctly, he told me when I interviewed him at his home in Toronto, he does not “want to promote supernatural thinking.”

More significantly, both his earlier horror films and his later more literary films eschew the thematic underpinning virtually every Hollywood film ever: the battle between good and evil. Cronenberg’s films do not provide the visual and aural clues that conventional Hollywood cinema uses to denote good and evil. His heroes are not particularly altruistic or, indeed, heroic. The protagonists of several of his films [SPOILER ALERT], including Videodrome, The Fly and Dead Ringers die—but their deaths are neither redemptive nor sacrificial, nor do they result in any kind of triumphant return, symbolic or otherwise.

Many of his films do not have traditional villains. Even his seemingly conventional antagonists, from the sex parasites in Shivers to the multinational corporation Spectacular Optical in Videodrome to Naked Lunch’s Dr. Benway, are sinister and scary, but function as necessary agents of change.

When Cronenberg does use religious imagery to suggest evil, it is neither supernatural nor transcendent. Rather, his religious imagery evokes authoritarian institutions. Dead Ringers, based on a true story of twin gynecologists’ descent into madness and addiction, includes examination scenes set in the Mantle Clinic, their medical practice. The clinic functions as a kind of quasi-religious institution and the scenes are terrifying (even though this is not at all a traditional horror film), inasmuch as they show the power that doctors have over patients, and that men have over women (see Image).

In both his personal philosophy and his films, David Cronenberg sees no need for transcendence, or for the fulfillment of the hero’s quest, or for cosmic reward and punishment. And yet his films wrestle with the same questions of meaning that our favorite “religious” films do (questions of sex and death, power and desire, family and society, identity and transformation) but that do so in a uniquely nonreligious way. The Oscars may never give Cronenberg his due, but anyone interested in religion, film and their relationship, needs to.

Elijah Siegler is an Associate Professor of Religious Studies at the College of Charleston. His article “David Cronenberg: The secular auteur as critic of religion” was recently published in the Journal of the American Academy of Religion.

The Journal of the American Academy of Religion is generally considered to be the top academic journal in the field of religious studies. This international quarterly journal publishes top scholarly articles that cover the full range of world religious traditions together with provocative studies of the methodologies by which these traditions are explored.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only television and film articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

The post Do the Oscars snub films without redemptive messages? appeared first on OUPblog.