new posts in all blogs

Viewing: Blog Posts Tagged with: Writing Emotion, Most Recent at Top [Help]

Results 1 - 5 of 5

How to use this Page

You are viewing the most recent posts tagged with the words: Writing Emotion in the JacketFlap blog reader. What is a tag? Think of a tag as a keyword or category label. Tags can both help you find posts on JacketFlap.com as well as provide an easy way for you to "remember" and classify posts for later recall. Try adding a tag yourself by clicking "Add a tag" below a post's header. Scroll down through the list of Recent Posts in the left column and click on a post title that sounds interesting. You can view all posts from a specific blog by clicking the Blog name in the right column, or you can click a 'More Posts from this Blog' link in any individual post.

Guest Post by Peter Langella

When I first began writing seriously, I was just telling stories. I wasn’t thinking about plot or structure or the concrete and abstract desires of my characters. Sure, a lot of that found its way into my drafts, but it wasn’t my focus when I brainstormed or sat at the keyboard.

When I first began writing seriously, I was just telling stories. I wasn’t thinking about plot or structure or the concrete and abstract desires of my characters. Sure, a lot of that found its way into my drafts, but it wasn’t my focus when I brainstormed or sat at the keyboard.

That all changed when I become a writing student at Vermont College of Fine Arts. My faculty mentors and talented classmates made me question my intentions in every scene. Were my characters learning, failing, growing, or changing? Was my plot moving forward? Was I creating an emotional arc for my characters that future readers could connect with?

Because of questions like these (among the many other things I learned), I grew exponentially as a writer during my MFA experience. I’m now gaining confidence with my writing voice, and my drafting toolbox is larger and much more accessible.

However, the question I struggle with on a daily basis is the one about character emotions and reader connection. This literally keeps me up at night. Many, many nights. I used to think that I didn’t need to worry about a potential reader. Just be true to your characters, I’d tell myself. Write the story that needs to be written, I’d hear my past professors saying.

Just write the truth, for goodness sake!

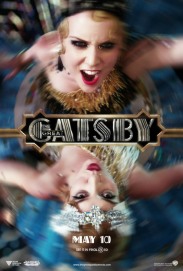

Then I watched Baz Luhrmann’s film adaptation of The Great Gatsby. I was blown away, specifically by his use of modern music in the 1920’s setting. By choosing a soundtrack that features Jay-Z, Jack White, Beyoncé, Florence & the Machine, and many other contemporary artists, Luhrmann isn’t only telling the characters’ stories, he is speaking directly to the audience.

Then I watched Baz Luhrmann’s film adaptation of The Great Gatsby. I was blown away, specifically by his use of modern music in the 1920’s setting. By choosing a soundtrack that features Jay-Z, Jack White, Beyoncé, Florence & the Machine, and many other contemporary artists, Luhrmann isn’t only telling the characters’ stories, he is speaking directly to the audience.

Now, I’m fully aware that Luhrmann’s music choices made most critics cringe, but I think it was extremely innovative, and similar choices can certainly be used by writers to make our books more relatable.

Seriously. I’m not crazy.

For example, during the first huge party that narrator Nick Carraway attends at Gatsby’s mansion, Luhrmann chooses to blare techno behind the visuals with vocals by Fergie and just a tiny hint of horns from the 1920’s. It’s jarring for the viewer, but it works because the character and viewer are experiencing the exact same thing. Nick Carraway has never heard music like this before, and he’s never been to a party so lavish. He’s completely out of his comfort zone. Viewers feel the same way. Most of us have never been to a party like that, either, and we’ve definitely never heard music like that paired with the visuals on the screen. We’re completely out of our comfort zone, too. If Luhrmann simply chose a jazz number new to Long Island that summer, Carraway would probably be feeling the same. He would still be blown away by the newness of the situation. But we wouldn’t be. We’d be thinking about the nice period piece we’re watching with timeless jazz music authentic to the era. We wouldn’t be feeling the exact same thing as the character, and the scene would be much less effective for that reason.

That’s what keeps me up at night. How can I – without the sounds and visuals that Luhrmann has at his disposal – create that exact connection?

Or, at least, how can I get it close?

In my current work-in-progress, one of my main characters is the son of a presidential candidate. Obviously, most people don’t know what it feels like to go through that. Neither do I. But many people know what it feels like to have a detached parent or someone at school who doesn’t like you as much as you like them or a friend who can’t talk for more than two minutes without making reference to some book or movie or TV show they watched recently.

The musicality, so to speak, is what happens in the background. It’s what the story is about, even though a hundred people could outline the plot and not mention these smaller items. These items that (hopefully) create an intense bond between the characters and a potential reader.

When I read Looking for Alaska, I was blown away by the scenes where Pudge and The Captain hang out in their dorm room. Maybe it’s because I went to boarding school, so I could understand and appreciate the rhythm of the monotony. But maybe it was because that’s where the characters figured out who they were. When I think about that book, I don’t think about Alaska Young or any other characters or anything any of the other characters did. I only think about those quiet scenes where nothing and everything happened for me all at the same time.

When I read Looking for Alaska, I was blown away by the scenes where Pudge and The Captain hang out in their dorm room. Maybe it’s because I went to boarding school, so I could understand and appreciate the rhythm of the monotony. But maybe it was because that’s where the characters figured out who they were. When I think about that book, I don’t think about Alaska Young or any other characters or anything any of the other characters did. I only think about those quiet scenes where nothing and everything happened for me all at the same time.

So, whether you’re famous like Baz Luhrmann or John Green, or you’re just someone trying to write their heart out like me, take another look at your draft and ask yourself if there’s any room for musicality in it. Ask yourself if there’s a way for your characters to connect with readers on a profound level, even if it happens in a small or weird way that might not seem to have anything to do with your story. It could be a scene from the roaring 20’s with techno music or a chapter where two friends sit around talking about nothing, but it will probably be something brilliant that only you and your characters can team up to create.

Trust me, when you’re up at night thinking about it, I’ll be up thinking about my stuff, too.

Peter Patrick Langella holds an MFA in Writing for Children and Young Adults from Vermont College of Fine Arts. He lives and writes in Vermont and thinks elevenses should be recognized by his employer.

Peter Patrick Langella holds an MFA in Writing for Children and Young Adults from Vermont College of Fine Arts. He lives and writes in Vermont and thinks elevenses should be recognized by his employer.

Other posts by Peter:

Guest Post by Peter Langella

When I first began writing seriously, I was just telling stories. I wasn’t thinking about plot or structure or the concrete and abstract desires of my characters. Sure, a lot of that found its way into my drafts, but it wasn’t my focus when I brainstormed or sat at the keyboard.

When I first began writing seriously, I was just telling stories. I wasn’t thinking about plot or structure or the concrete and abstract desires of my characters. Sure, a lot of that found its way into my drafts, but it wasn’t my focus when I brainstormed or sat at the keyboard.

That all changed when I become a writing student at Vermont College of Fine Arts. My faculty mentors and talented classmates made me question my intentions in every scene. Were my characters learning, failing, growing, or changing? Was my plot moving forward? Was I creating an emotional arc for my characters that future readers could connect with?

Because of questions like these (among the many other things I learned), I grew exponentially as a writer during my MFA experience. I’m now gaining confidence with my writing voice, and my drafting toolbox is larger and much more accessible.

However, the question I struggle with on a daily basis is the one about character emotions and reader connection. This literally keeps me up at night. Many, many nights. I used to think that I didn’t need to worry about a potential reader. Just be true to your characters, I’d tell myself. Write the story that needs to be written, I’d hear my past professors saying.

Just write the truth, for goodness sake!

Then I watched Baz Luhrmann’s film adaptation of The Great Gatsby. I was blown away, specifically by his use of modern music in the 1920’s setting. By choosing a soundtrack that features Jay-Z, Jack White, Beyoncé, Florence & the Machine, and many other contemporary artists, Luhrmann isn’t only telling the characters’ stories, he is speaking directly to the audience.

Then I watched Baz Luhrmann’s film adaptation of The Great Gatsby. I was blown away, specifically by his use of modern music in the 1920’s setting. By choosing a soundtrack that features Jay-Z, Jack White, Beyoncé, Florence & the Machine, and many other contemporary artists, Luhrmann isn’t only telling the characters’ stories, he is speaking directly to the audience.

Now, I’m fully aware that Luhrmann’s music choices made most critics cringe, but I think it was extremely innovative, and similar choices can certainly be used by writers to make our books more relatable.

Seriously. I’m not crazy.

For example, during the first huge party that narrator Nick Carraway attends at Gatsby’s mansion, Luhrmann chooses to blare techno behind the visuals with vocals by Fergie and just a tiny hint of horns from the 1920’s. It’s jarring for the viewer, but it works because the character and viewer are experiencing the exact same thing. Nick Carraway has never heard music like this before, and he’s never been to a party so lavish. He’s completely out of his comfort zone. Viewers feel the same way. Most of us have never been to a party like that, either, and we’ve definitely never heard music like that paired with the visuals on the screen. We’re completely out of our comfort zone, too. If Luhrmann simply chose a jazz number new to Long Island that summer, Carraway would probably be feeling the same. He would still be blown away by the newness of the situation. But we wouldn’t be. We’d be thinking about the nice period piece we’re watching with timeless jazz music authentic to the era. We wouldn’t be feeling the exact same thing as the character, and the scene would be much less effective for that reason.

That’s what keeps me up at night. How can I – without the sounds and visuals that Luhrmann has at his disposal – create that exact connection?

Or, at least, how can I get it close?

In my current work-in-progress, one of my main characters is the son of a presidential candidate. Obviously, most people don’t know what it feels like to go through that. Neither do I. But many people know what it feels like to have a detached parent or someone at school who doesn’t like you as much as you like them or a friend who can’t talk for more than two minutes without making reference to some book or movie or TV show they watched recently.

The musicality, so to speak, is what happens in the background. It’s what the story is about, even though a hundred people could outline the plot and not mention these smaller items. These items that (hopefully) create an intense bond between the characters and a potential reader.

When I read Looking for Alaska, I was blown away by the scenes where Pudge and The Captain hang out in their dorm room. Maybe it’s because I went to boarding school, so I could understand and appreciate the rhythm of the monotony. But maybe it was because that’s where the characters figured out who they were. When I think about that book, I don’t think about Alaska Young or any other characters or anything any of the other characters did. I only think about those quiet scenes where nothing and everything happened for me all at the same time.

When I read Looking for Alaska, I was blown away by the scenes where Pudge and The Captain hang out in their dorm room. Maybe it’s because I went to boarding school, so I could understand and appreciate the rhythm of the monotony. But maybe it was because that’s where the characters figured out who they were. When I think about that book, I don’t think about Alaska Young or any other characters or anything any of the other characters did. I only think about those quiet scenes where nothing and everything happened for me all at the same time.

So, whether you’re famous like Baz Luhrmann or John Green, or you’re just someone trying to write their heart out like me, take another look at your draft and ask yourself if there’s any room for musicality in it. Ask yourself if there’s a way for your characters to connect with readers on a profound level, even if it happens in a small or weird way that might not seem to have anything to do with your story. It could be a scene from the roaring 20’s with techno music or a chapter where two friends sit around talking about nothing, but it will probably be something brilliant that only you and your characters can team up to create.

Trust me, when you’re up at night thinking about it, I’ll be up thinking about my stuff, too.

Peter Patrick Langella holds an MFA in Writing for Children and Young Adults from Vermont College of Fine Arts. He lives and writes in Vermont and thinks elevenses should be recognized by his employer.

Peter Patrick Langella holds an MFA in Writing for Children and Young Adults from Vermont College of Fine Arts. He lives and writes in Vermont and thinks elevenses should be recognized by his employer.

Other posts by Peter:

The objective correlative is a fantastic technique that you can use to create emotion in your writing. It empowers writers to move away from abstraction (i.e. using direct words like angry, sad, or afraid, which are abstract to the reader) and color a character’s emotion with imagery, metaphor, and meaning.

The objective correlative is a fantastic technique that you can use to create emotion in your writing. It empowers writers to move away from abstraction (i.e. using direct words like angry, sad, or afraid, which are abstract to the reader) and color a character’s emotion with imagery, metaphor, and meaning.

Originally coined as a literary term by T.S. Eliot in his essay on Hamlet, Eliot explains that the objective correlative as:

“…a set of objects, a situation, a chain of events which shall be the formula of that Particular emotion; such that when the external facts, which must terminate in sensory experience, are given, the emotion is immediately evoked” (qtd. in J. A. Cuddon’s Dictionary of Literary Terms, page 647).

I know, that sounds like literary psychobabble, let’s break it down…

Say, your character has experienced a loss and you want to evoke sadness and longing in the reader. Objective correlative is a technique where the character never tells the reader what she is feeling. Instead she evokes that feeling through sensory experiences and description of her environment.

Take a look at this example from Jacqueline Woodson’s novel Beneath a Meth Moon:

Take a look at this example from Jacqueline Woodson’s novel Beneath a Meth Moon:

“I sat up front with Daddy, stared at the flat land as we drove. Big sky that I couldn’t look up into without thinking about M’lady and Mama. Green land moving fast toward us, then passing us by. Farms and fields. Whole stretches with nothing at all” (44).

What does this passage make you feel? What do you know about the narrator and her emotional state?

For me, the description of the flat land and the big sky gives a sense of being small. The fact that the narrator (Laurel) can’t look up into the sky adds an additional layer of feeling. She’s overwhelmed by something large. Additionally, that large object is invisible and everywhere. Laurel then links this image with M’lady and Mama. Do we know what happened to these two people in this passage? Not necessarily, but we can make a guess from the description of the landscape.

In the remaining sentences of the passage, the imagery focuses on green land moving past Laurel. A green field is initially a positive image, relating to good health and growth. But it moves fast and Laurel is unable to hold onto the good things, even if she wanted to. The paragraph ends with the final image of flat land stretching out forever with nothing to offer. Can you feel the desperation, sadness, and a loss of hope in this build-up of images? Nowhere does the narrator mention how she feels. Instead she describes her environment, and the unique way she sees these images, evokes her inner state for the reader. This is the objective correlative at work! It’s also a lot more interesting to read than if the author said: Laurel felt depressed.

I think it’s also important to note that characters are seldom self-aware. As humans, we don’t often think to ourselves: “Man, I feel sad!” We simply experience our emotions and live our lives. We don’t reflect on what those emotions are or why we feel them. We act! We observe. We react. Let objective correlative help you to keep your characters authentic, alive, and in the moment.

Try out the objective correlative for yourself, with this great exercise:

Try out the objective correlative for yourself, with this great exercise:

Write a scene in which a man describes a body of water (i.e. ocean, river, pond, etc.) after having just murdered someone. However, the man can never mention the murder or any of the details related to the murder. Have fun!

Want to know more about Objective Correlative? Read these great articles:

What Is The Objective Correlative

Meaning and Metaphor

The objective correlative is a fantastic technique that you can use to create emotion in your writing. It empowers writers to move away from abstraction (i.e. using direct words like angry, sad, or afraid, which are abstract to the reader) and color a character’s emotion with imagery, metaphor, and meaning.

The objective correlative is a fantastic technique that you can use to create emotion in your writing. It empowers writers to move away from abstraction (i.e. using direct words like angry, sad, or afraid, which are abstract to the reader) and color a character’s emotion with imagery, metaphor, and meaning.

Originally coined as a literary term by T.S. Eliot in his essay on Hamlet, Eliot explains that the objective correlative as:

“…a set of objects, a situation, a chain of events which shall be the formula of that Particular emotion; such that when the external facts, which must terminate in sensory experience, are given, the emotion is immediately evoked” (qtd. in J. A. Cuddon’s Dictionary of Literary Terms, page 647).

I know, that sounds like literary psychobabble, let’s break it down…

Say, your character has experienced a loss and you want to evoke sadness and longing in the reader. Objective correlative is a technique where the character never tells the reader what she is feeling. Instead she evokes that feeling through sensory experiences and description of her environment.

Take a look at this example from Jacqueline Woodson’s novel Beneath a Meth Moon:

Take a look at this example from Jacqueline Woodson’s novel Beneath a Meth Moon:

“I sat up front with Daddy, stared at the flat land as we drove. Big sky that I couldn’t look up into without thinking about M’lady and Mama. Green land moving fast toward us, then passing us by. Farms and fields. Whole stretches with nothing at all” (44).

What does this passage make you feel? What do you know about the narrator and her emotional state?

For me, the description of the flat land and the big sky gives a sense of being small. The fact that the narrator (Laurel) can’t look up into the sky adds an additional layer of feeling. She’s overwhelmed by something large. Additionally, that large object is invisible and everywhere. Laurel then links this image with M’lady and Mama. Do we know what happened to these two people in this passage? Not necessarily, but we can make a guess from the description of the landscape.

In the remaining sentences of the passage, the imagery focuses on green land moving past Laurel. A green field is initially a positive image, relating to good health and growth. But it moves fast and Laurel is unable to hold onto the good things, even if she wanted to. The paragraph ends with the final image of flat land stretching out forever with nothing to offer. Can you feel the desperation, sadness, and a loss of hope in this build-up of images? Nowhere does the narrator mention how she feels. Instead she describes her environment, and the unique way she sees these images, evokes her inner state for the reader. This is the objective correlative at work! It’s also a lot more interesting to read than if the author said: Laurel felt depressed.

I think it’s also important to note that characters are seldom self-aware. As humans, we don’t often think to ourselves: “Man, I feel sad!” We simply experience our emotions and live our lives. We don’t reflect on what those emotions are or why we feel them. We act! We observe. We react. Let objective correlative help you to keep your characters authentic, alive, and in the moment.

Try out the objective correlative for yourself, with this great exercise:

Try out the objective correlative for yourself, with this great exercise:

Write a scene in which a man describes a body of water (i.e. ocean, river, pond, etc.) after having just murdered someone. However, the man can never mention the murder or any of the details related to the murder. Have fun!

Want to know more about Objective Correlative? Read these great articles:

What Is The Objective Correlative

Meaning and Metaphor

By Jeff Schill

I love dialogue.

To me, a story is all about the characters. And I especially enjoy when these characters interact with one other. But at the same time, dialogue can fall flat when it does not resonate or make the reader feel something.

Dialogue is much more than just the words on the page. Dialogue is largely about how we, as writers, express our characters’ emotions and how the reader, in return, responds to these emotions.

Creating Emotion in Dialogue

In 1967 Albert Mehrabian, a professor at Stanford University, specifically looked at emotion and communication. In his study, he concluded that 55% of emotion is communicated through a person’s nonverbal cues: facial expressions, gestures, posture and movement.

Nonverbals

To emphasize how powerful nonverbal behavior can be in dialogue let’s look at a few lines where I took the nonverbal cue away.

- “And a place in Beverly Hills. Next door to your place,” he says.

- “Be there or Be-ware,” she said.

Notice how bland and unemotional these lines are. Now let’s add the nonverbal cue and see how it changes the lines.

Facial Expressions:

- “And a place in Beverly Hills.” She cocks her eyebrow. “Next door to your place,” he says. (178) – Blink and Caution

Movement

- “Be there or Be-ware!” she said, and slammed the phone down. (243) – Dead End in Norvelt.

Notice how in each one of these examples the nonverbal cue adds intensity or emotion to the line. In the first example, the cocked eyebrow gives us a sense of skepticism and in the last sentence the slamming of the phone gives us anger. Think about how using a character’s facial expressions, gestures, movement and posture may compliment or add emotion to the dialogue.

Paraverbal (How we say what we say)

Mehrabian went on to state that 38% of emotion is communicated through a person’s paraverbals: how they say what they say. Look at this example from Polly Horvath’s One Year in Coal Harbor and notice how she emphasizes certain words to increase the emotion of the dialogue.

“Oh really? Well where does he think I went to cooking school?”

“I don’t think he thinks you did. I think he thinks you just, you know, picked it up.”

“PICKED IT UP?” Miss Bowzer’s eyes were afire and her neck was getting blotches of red. Maybe I’d gone too far.

“You know, like, on the street.”

“ON THE STREET? I’ll have him know I went to the Cordon Bleu in Paris for an entire semester!” (42)

Through the use of typography the reader can begin to feel Miss Bowzer’s frustration. Horvath is using the character’s paraverbals to stress the emotion.

Now look at this example from Tim Wynne-Jones’s Blink & Caution and notice how he uses hesitation in the dialogue to create emotion.

“After what happened… after what I did…” She finds her mouth is dry. She remembers her soda, takes a swig.

“I’m listening,” he says.

“After that… what I was talking about… I felt like nothing was real. It was” – and this is new to her, the first time she’s thought of it- “it was as if I were the one who was dead. I killed my brother. But I killed myself, only I didn’t know it. And all this – everything that has happened since then is just…” (223)

The character’s hesitation in this passage shows her struggle and reluctance at opening up to the truth. By emphasizing how she says what she says, Wynne-Jones is heightening the emotion within the dialogue.

Often as a writer we think about our dialogue only through the lens of the words our character use. However, more often than not it is the emotion behind these words that create a reader reaction. We want our dialogue to make the reader feel something; to stir emotion. Challenge yourself to use your character’s nonverbal and paraverbals to create dialogue that resonates with the reader.

*For a discussion on pacing, spacing, metaphors, objective correlatives and the actual words we use to create emotion in dialogue you’ll have to persuade Ingrid to invite me back.

Jeff Schill holds an MFA in Writing for Children and Young Adults from Vermont College of Fine Arts and is a proud member of the Dystropian family. He lives, works and writes in Milwaukee, is deathly afraid of dogs and is completely creeped out by the stains found in library books.

Jeff Schill holds an MFA in Writing for Children and Young Adults from Vermont College of Fine Arts and is a proud member of the Dystropian family. He lives, works and writes in Milwaukee, is deathly afraid of dogs and is completely creeped out by the stains found in library books.

You can read more of Jeff’s work on his blog: http://jeffschill.blogspot.com/

When I first began writing seriously, I was just telling stories. I wasn’t thinking about plot or structure or the concrete and abstract desires of my characters. Sure, a lot of that found its way into my drafts, but it wasn’t my focus when I brainstormed or sat at the keyboard.

When I first began writing seriously, I was just telling stories. I wasn’t thinking about plot or structure or the concrete and abstract desires of my characters. Sure, a lot of that found its way into my drafts, but it wasn’t my focus when I brainstormed or sat at the keyboard. Then I watched Baz Luhrmann’s film adaptation of The Great Gatsby. I was blown away, specifically by his use of modern music in the 1920’s setting. By choosing a soundtrack that features Jay-Z, Jack White, Beyoncé, Florence & the Machine, and many other contemporary artists, Luhrmann isn’t only telling the characters’ stories, he is speaking directly to the audience.

Then I watched Baz Luhrmann’s film adaptation of The Great Gatsby. I was blown away, specifically by his use of modern music in the 1920’s setting. By choosing a soundtrack that features Jay-Z, Jack White, Beyoncé, Florence & the Machine, and many other contemporary artists, Luhrmann isn’t only telling the characters’ stories, he is speaking directly to the audience. When I read Looking for Alaska, I was blown away by the scenes where Pudge and The Captain hang out in their dorm room. Maybe it’s because I went to boarding school, so I could understand and appreciate the rhythm of the monotony. But maybe it was because that’s where the characters figured out who they were. When I think about that book, I don’t think about Alaska Young or any other characters or anything any of the other characters did. I only think about those quiet scenes where nothing and everything happened for me all at the same time.

When I read Looking for Alaska, I was blown away by the scenes where Pudge and The Captain hang out in their dorm room. Maybe it’s because I went to boarding school, so I could understand and appreciate the rhythm of the monotony. But maybe it was because that’s where the characters figured out who they were. When I think about that book, I don’t think about Alaska Young or any other characters or anything any of the other characters did. I only think about those quiet scenes where nothing and everything happened for me all at the same time. Peter Patrick Langella holds an MFA in Writing for Children and Young Adults from Vermont College of Fine Arts. He lives and writes in Vermont and thinks elevenses should be recognized by his employer.

Peter Patrick Langella holds an MFA in Writing for Children and Young Adults from Vermont College of Fine Arts. He lives and writes in Vermont and thinks elevenses should be recognized by his employer.

What a great post! I love the Gatsby movie example–what a powerful way to express an elusive idea. This definitely got me thinking. Thanks, Peter!

This is great! I really enjoy your posts. Innovation and reader connection keep me up at night too!