By Steven A. Cook As Cairo's citizens drove along the Autostrad [last] week, they were greeted with four enormous billboards featuring pictures of Turkish Prime Minister Recep Tayyip Erdogan. With Turkish and Egyptian flags, the signs bore the message, "With United Hands for the Future." Erdogan's visit marks a bold development in Turkey's leadership in the region. The hero's welcome he received at the airport reinforced the popular perception: Turkey is a positive force, uniquely positioned to guide the Middle East's ongoing transformation.

Viewing: Blog Posts Tagged with: mubarak, Most Recent at Top [Help]

Results 1 - 5 of 5

Blog: OUPblog (Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags: Middle East, Turkey, Revolution, *Featured, mubarak, gaddafi, qaddafi, dictator, Law & Politics, steven a. cook, the struggle for egypt, Recep Tayyip Erdogan, erdogan, Add a tag

Blog: OUPblog (Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags: Arab, brotherhood, david cameron, Muslim Brotherhood, *Featured, mubarak, Geneive Abdo, mecca and main street, no god but god, sharia, abdo, egypt’s, wasat, geneive, Law, Religion, Politics, elections, Current Events, Middle East, Islam, Egypt, muslim, Add a tag

By Geneive Abdo

Over the past several weeks, leaders of Egypt’s Muslim Brotherhood have placed on public display the lessons they have learned as Egypt’s officially banned but most influential social and political movement by trying to pre-empt alarmist declarations that the country is now headed for an Iran-style theocracy.

Members of the venerable Brotherhood, founded in 1928 by an Egyptian school teacher to revitalize Islam and oppose British colonial rule, have so far stated no plans to run a candidate in the next presidential election, and they surprised many by their halting participation in the transitional government, after the fall of President Hosni Mubarak. They also have made it clear that they have no desire to seek a majority in the Egyptian parliament, when free elections are held, as promised by Egypt’s current military rulers. In fact, the Brotherhood has voiced its commitment to work with all groups within the opposition – including the secular-leaning youth who inspired the revolution – without demanding a leading role for itself.

These gestures have produced two reactions from Western governments and other international actors heavily invested in Egypt’s future: Some simply see this as evidence that there is no reason to fear the Brotherhood will become a dominant force in the next government.

Others view the Brotherhood’s public declarations with skepticism, saying the promises are designed simply to head off any anxiety over the future influence and scope of the religious-based movement. For example, British Minister David Cameron, who last week became the first foreign leader to visit Egypt after Mubarak’s downfall, refused to meet Brotherhood leaders, saying he wanted the people to see there are political alternatives to “extreme” Islamist opposition. Such simplistic characterization of the Muslim Brotherhood simply echoes Mubarak’s long-term tactic to scare the West into supporting his authoritarian rule as the best alternative to Islamic extremism.

But the future on the horizon for the Brotherhood lies most likely somewhere between these divergent views. Now that Egyptians have freed themselves from decades of restraint and fear, a liberalized party system will logically follow, reflecting the values, aspirations and religious beliefs of Egyptian society as a whole.

What the outside world seems to have missed during the many decades since the Brotherhood was banned is the fact that the movement has never been a political and social force somehow detached from Egyptian society. Rather, the widespread popularity of the movement – which is fragmented along generational lines – can be best explained by the extent to which it reflects the views of a vast swathe of Egyptians.

The Brotherhood has waited patiently for society to evolve beyond the Free Officers movement of former President Gamal Abdel Nasser. Beginning in the early 1990s, it was clear that Islamization was taking hold in Egypt. In my book, No God But God: Egypt and the Triumph of Islam, which documented the societal transformation from a secular to more religious Egypt during the 1990s, I made it clear that the Brotherhood was on the rise. This was in part responsible for the Brotherhood’s strong showing in parliamentary elections in 2005, when they ran candidates as independents because Egyptian law prohibits religiously-based parties to run candidates in elections.

The question now is wh

Blog: OUPblog (Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags: Cuba, internet, Technology, Politics, Current Events, facebook, Media, Middle East, twitter, Egypt, Revolution, Dennis Baron, cairo, A Better Pencil, *Featured, mubarak, Ben Ali, Add a tag

By Dennis Baron

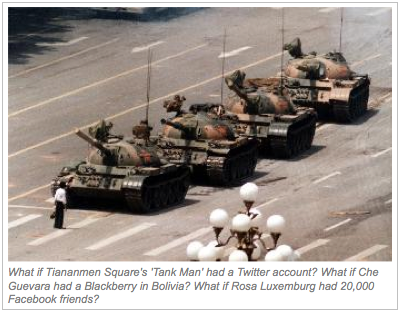

Western observers have been celebrating the role of Twitter, Facebook, smartphones, and the internet in general in facilitating the overthrow of President Hosni Mubarak in Egypt last week. An Egyptian Google employee, imprisoned for rallying the opposition on Facebook, even became for a time a hero of the insurgency. The Twitter Revolution was similarly credited with fostering the earlier ousting of Tunisia’s Ben Ali, and supporting Iran’s green protests last year, and it’s been instrumental in other outbreaks of resistance in a variety of totalitarian states across the globe. If only Twitter had been around for Tiananmen Square, enthusiasts retweeted one another. Not bad for a site that started as a way to tell your friends what you had for breakfast.

But skeptics point out that the crowds in Cairo’s Tahrir Square continued to grow during the five days that the Mubarak government shut down the internet; that only nineteen percent of Tunisians have online access; that while the Iran protests may have been tweeted round the world, there were few Twitter users actually in-country; and that although Americans can’t seem to survive without the constant stimulus of digital multitasking, much of the rest of the world barely notices when the cable is down, being preoccupied instead with raising literacy rates, fighting famine and disease, and finding clean water, not to mention a source of electricity that works for more than an hour every day or two.

But skeptics point out that the crowds in Cairo’s Tahrir Square continued to grow during the five days that the Mubarak government shut down the internet; that only nineteen percent of Tunisians have online access; that while the Iran protests may have been tweeted round the world, there were few Twitter users actually in-country; and that although Americans can’t seem to survive without the constant stimulus of digital multitasking, much of the rest of the world barely notices when the cable is down, being preoccupied instead with raising literacy rates, fighting famine and disease, and finding clean water, not to mention a source of electricity that works for more than an hour every day or two.

It’s true that the internet connects people, and it’s become an unbeatable source of information—the Egyptian revolution was up on Wikipedia faster than you could say Wolf Blitzer. The telephone also connected and informed faster than anything before it, and before the telephone the printing press was the agent of rapid-fire change. All these technologies can foment revolution, but they can also be used to suppress dissent.

You don’t have to master the laws of physics to observe that for every revolutionary manifesto there’s an equal and opposite volley of government propaganda. For every eye-opening book there’s an index librorum prohibitorum—an official do-not-read list—or worse yet, a bonfire. For every phone tree organizing a protest rally there’s a warrantless wiretap waiting to throw the rally-goers in jail. And for every revolutionary internet site there’s a firewall, or in the case of Egypt, a switch that shuts it all down. Cuba is a country well-known for blocking digital access, but responding to events in Egypt and the small but scary collection of island bloggers, El Lider’s government is sponsoring a dot gov rebuttal, a cadre of official counterbloggers spreading the party line to the still small number of Cubans able to get online—about ten percent can access the official government-controlled ’net—or get a cell phone signal in their ’55 Chevys.

You don’t have to master the laws of physics to observe that for every revolutionary manifesto there’s an equal and opposite volley of government propaganda. For every eye-opening book there’s an index librorum prohibitorum—an official do-not-read list—or worse yet, a bonfire. For every phone tree organizing a protest rally there’s a warrantless wiretap waiting to throw the rally-goers in jail. And for every revolutionary internet site there’s a firewall, or in the case of Egypt, a switch that shuts it all down. Cuba is a country well-known for blocking digital access, but responding to events in Egypt and the small but scary collection of island bloggers, El Lider’s government is sponsoring a dot gov rebuttal, a cadre of official counterbloggers spreading the party line to the still small number of Cubans able to get online—about ten percent can access the official government-controlled ’net—or get a cell phone signal in their ’55 Chevys.

All new means of communication bring with them an irrepressible excitement as they expand literacy and open up new knowledge, but in certain quarters they also spark fear and distrust. At the very least, civil and religious authorities start insisting on an imprimatur—literally, a permission to print—to license communication and censor content, channeling it al

Blog: OUPblog (Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags: Politics, Middle East, Egypt, Revolution, federalist papers, cairo, Elvin Lim, anti-intellectual presidency, *Featured, Hosni Mubarak, mubarak, hosni, Publius, 1787, democracy, Add a tag

By Elvin Lim

As the situation continues to unfold in Egypt, and as the White House continues to walk a fine line between support for democracy and support for a new regime which may not be as pro-American as Hosni Mubarak’s was, Publius, the author of the Federalist Papers may lend us some wisdom.

It may surprise some people, but Publius was no fan of democracy. “Democracies have ever been spectacles of turbulence and contention,” Publius wrote in Number 10. The mob cannot rule, though the mob may delegate power to those who can. And that was the genius of 1787 – a full decade after the American revolution, it bears repeating. Revolutions are negative acts where old worlds are shattered; founding, on the other hand, is a positive act, where a new world is created. Egypt has had her fair share of revolutions, and it is high time for a founding that will make a future revolution unnecessary.

But who should the supporters at Tahrir Square anoint to be the leader of a new Egypt? Enlightened statesmen will not always be at the helm, Publius warned us. The irony of this weekend’s hagiographic celebration of Ronald Reagan’s 100th birthday is that the Framers of the US Constitution had hoped to create a system so that we did not have to wait for virtuous men any more, as the history of a capricious world had only done before. Egypt will become a republic when she no longer awaits a Nasser or a Sadat or a Mubarak. Even ElBaradei should not be mistaken for a messiah.

How would Publius have handled the Muslim Brotherhood? Certainly not by banning it, as Hosni Mubarak did. Instead, Publius would have proposed that Egypt bring as many political and religious groups as possible to the negotiating table, and let ambition counteract ambition. “A religious sect may degenerate into a political faction in a part of the Confederacy,” Publius wrote, “but the variety of sects dispersed over the entire face of it must secure the national councils against any danger from that source.” If the Muslim Brotherhood supports suppression, then the solution to it is not more suppression, but to engulf it with groups who support liberty.

Finally, Publius’ greatest innovation arguably laid in the fact that he proposed an entirely new constitution, not a mere amendment to the Articles of Confederation, as was the charge of the Continental Congress in 1787. Vice-president Omar Suleiman is apparently now overseeing a committee to oversee amendments to the Constitution, focusing in particular on provisions that would allow the Opposition to run for the Egyptian presidency. This is not a good idea because the Egyptian constitution needs more than piecemeal change. In particular, even the Opposition has been co-opted into believing that Egypt’s problems could be solved by having the right person assume control of the presidency. But the problem lies not just in the manner by which the president is selected, but in the size of the office. Publius stated it well in Number 51, “In framing a government which is to be administered by men over men, the great difficulty lies in this: you must first enable the government to control the governed; and in the next place

Blog: OUPblog (Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags: Politics, Middle East, Egypt, caption, Revolution, ciaro, riots, placards, cairo, mubarak, american university in cairo, Neil Hewison, Tahrir Square, tahrir, aucp, protesters, square, Current Events, *Featured, Add a tag

When the demonstrations began in Cairo last week, communication with the staff at our newest distribution partner, American University in Cairo Press was immediately disrupted. As most of our readers know, the Egyptian government suspended internet and cell phone service in Cairo, and the only way the AUCP representative in New York could contact the home office was via a spotty land line connection. Fortunately, we’ve since learned that all AUCP staff are safe and sound, and communication has improved somewhat in recent days. But as you’ll see from AUCP editorial director Neil Hewison’s harrowing account below, the Press itself – which is situated close to Tahrir Square – was directly affected by the unrest. We continue to wish our colleagues in Cairo well, and hope to have periodic updates from Neil in the days ahead.

We are all fine. Many dramatic events over the last few days. Particularly disturbing was the battle for the Interior Ministry just up the road from my house, which went on for eight hours on Saturday: we heard and watched the police firing tear gas and live fire (including automatic weapons) and the protesters ducking into back alleys to make and throw Molotov cocktails. Also very disturbing the violent clashes that are happening right now on Tahrir Square, while the army stand and watch.

I’ve been out each morning since Sunday, seen the destruction, the tanks on the streets, the neighborhood watch groups armed with sticks and knives, the civilians directing traffic rather more efficiently than the police ever did, and the protesters in Tahrir Square of all social hues, well organized, with their own food, drink, garbage, and security services in place, and with some very imaginative, witty placards: “Just go! My arms ache!” – held up by a 10-year old boy, “Talk to him in Hebrew, he might understand.” One man cradled a cat that carried its own mini-placard in English: “No Mubarak.” Another man sported a banner with the crescent and the cross and the simple statement “I am Egyptian.” They renamed the square Martyrs’ Square and painted the name in giant letters on the tarmac for the constantly circling helicopter to see. They set up a display of placards discarded as people went home at night, all set out on the pavement under the sign “Revolution Museum.”

Our AUC Press offices were trashed on Friday. The police had broken into the AUC to use the roof of our wing to fire on protesters at the junction of Sheikh Rihan and Qasr al-Aini (we found empty CS canisters and shotgun cartridges up there). And persons unknown ransacked our rooms. Drawers and files emptied, windows broken, cupboards and computers smashed. But it could have been much worse. Meanwhile, the violence may get worse before it gets better.

I’m well stocked with food and water, and there’s a good gang of neighborhood lads downstairs with makeshift weapons to keep our b