new posts in all blogs

Viewing: Blog Posts Tagged with: incomes, Most Recent at Top [Help]

Results 1 - 4 of 4

How to use this Page

You are viewing the most recent posts tagged with the words: incomes in the JacketFlap blog reader. What is a tag? Think of a tag as a keyword or category label. Tags can both help you find posts on JacketFlap.com as well as provide an easy way for you to "remember" and classify posts for later recall. Try adding a tag yourself by clicking "Add a tag" below a post's header. Scroll down through the list of Recent Posts in the left column and click on a post title that sounds interesting. You can view all posts from a specific blog by clicking the Blog name in the right column, or you can click a 'More Posts from this Blog' link in any individual post.

By: Maria Donnini,

on 3/6/2014

Blog:

OUPblog

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

earning,

clarendon,

incomes,

*Featured,

payments,

Simon Eliot,

author earnings,

author payment,

Clarendon Press Series,

History of Oxford University Press,

John Feather,

nonfiction authors,

Selborne Commission,

W. Aldis Wright,

aldis,

‘clarendon,

liddell,

Books,

History,

Media,

Oxford University Press,

wright,

British,

19th century,

Add a tag

By Simon Eliot and John Feather

In the 1860s, the introduction of its first named series of education books, the ‘Clarendon Press Series’ (CPS), encouraged Oxford University Press to standardize its payments to authors. Most of them were offered a very generous deal: 50 or 60% of net profits. These payments were made annually and were recorded in the minutes of the Press’ newly-established Finance Committee. The list of payments lengthened every year, as new titles were published and very few were ever allowed to go out of print. Some authors did very well from their association with the Press, but most earned very modest sums. Many of the books in the Clarendon Press Series yielded almost nothing to publisher or author; once we exclude the handful of exceptional cases, typical payments were in the range of £5 to £15 a year.

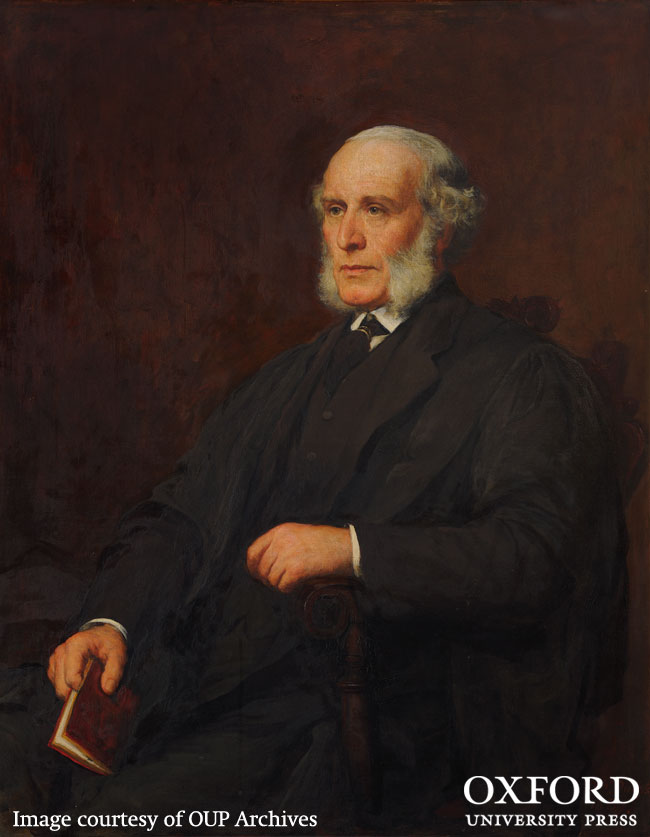

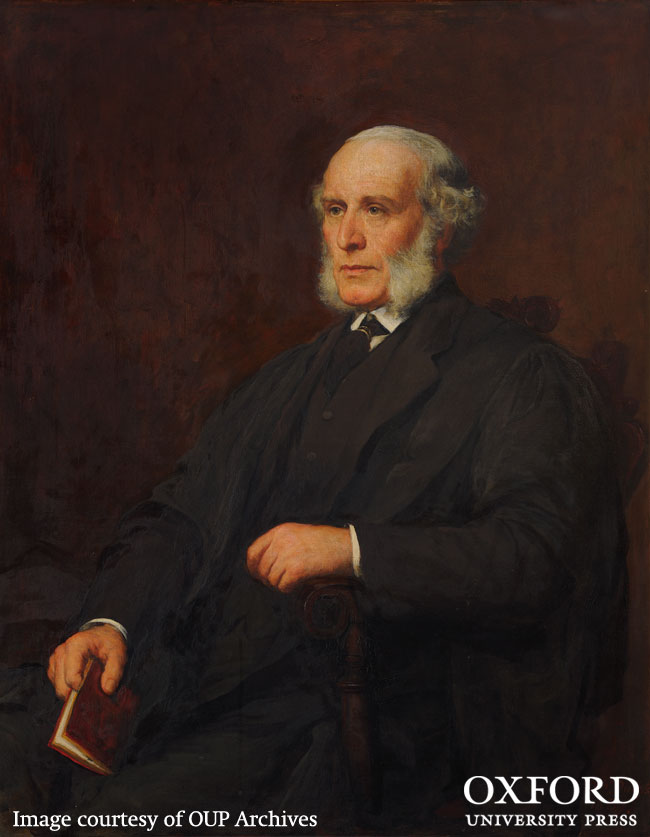

W. Aldis Wright.

The outstanding financial successes of the Clarendon Press Series were the editions of separate plays of Shakespeare intended for school pupils and (increasingly) university students. The first to be published was Macbeth in 1869, but it was the next to appear – Hamlet in 1873 – which became something like a bestseller. In its first year, Hamlet sold 3,380 copies; 20 years and five editions later, 73,140 copies had been accounted for to the editor, W. Aldis Wright (a fellow of Trinity College, Cambridge), who received over the years some £1,400 for this play alone. The whole CPS Shakespeare venture brought Wright an income of about £1,000 a year throughout much of the 1880s. To put this in context, the total of all royalties paid to authors in the late 1880s and early 1890s was about £5000 a year; in some years Wright was taking about 20% of that for his editions of Shakespeare alone.

A broader view of the Press’s payments to its authors on the Learned side can be gained by looking at three sample years: 1875, 1885, and 1895. In November 1875, the Finance Committee minutes listed 99 titles for which authors were being paid annual incomes, the total sum being paid out was £2,216. In November 1885, near the peak of publishing activity in the Clarendon Press Series, the Finance Committee minutes listed 238 titles generating revenue for their authors; they earned £4,740 between them. In November 1895, there were 240 titles leading to payments of £5,076. For most authors, their individual incomes were modest; in 1875, the median income was £7 16s, in 1885 it was £7 18s. However, in 1875 four authors and editors earned more than £100: Liddell and Scott received £372 each (for their Greek Lexicon), Aldis Wright received £220 (for various editions of Shakespeare’s plays), and Bishop Charles Wordsworth £152 (for his Greek Grammar). In 1885, eleven were earning more than £100, including Aldis Wright earning £934, Liddell and Scott each earning £350, Skeat earning £270 (for philological works), and Benjamin Jowett earning £261 (for editions of Plato’s works). In 1895, there were ten, including Aldis Wright with £578, J. B. Allen with £542 (for works on Latin grammar), and Liddell and Scott with £389 each.

These authorial incomes should be set against average academic incomes in Oxford. In the later nineteenth century, although there was much variation, the average annual income for a college fellow would be in the order of £600, usually made up of the fellowship dividend plus the tutorial stipend. In the wake of the Selborne Commission, in the early 1880s a reader would be paid £500, a sum might well be augmented by a fellowship dividend; professorships attracted £900 per annum. It is clear that, although most authors’ incomes were extremely small, the most successful authors, both inside and outside the Clarendon Press Series, were at their height earning a significant addition to their salaries through payments from the Press.

The incomes of the most successful were far in excess of what they would have earned had they sold their copyrights outright. On the other hand, those around the median probably earned less than a lump sum payment would have brought in or, at least, they had to wait longer for it. As a minor compensation to those who were paid small annual sums during this period – though it is unlikely that they would have known it – the purchasing power of the pound was rising between the mid-1860s and the mid-1890s, so their later small payments would have bought them more than their earlier small payments. The pound in a person’s pocket was actually worth more at the end of the nineteenth century than it had been at the beginning.

Simon Eliot is Professor of the History of the Book in the Institute of English Studies, School of Advanced Study, University of London. He is general editor of The History of Oxford University Press, and editor of its Volume II 1780-1896. John Feather, a former President of the Oxford Bibliographical Society, is a Professor at Loughborough University and the author of A History of British Publishing and many other works on the history of books and the book trade. He has contributed to both volumes I and II of The History of Oxford University Press.

With access to extensive archives, The History of Oxford University Press is the first complete scholarly history of the Press, detailing its organization, publications, trade, and international development. Read previous blog posts about the history of Oxford University Press.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only British history articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Image credit: William Aldis Wright (1831-1914), editor, Shakespeare Plays, the Clarendon Press Series (Walter William Ouless, 1887). (The Master and Fellows of Trinity College Cambridge) OUP Archives. Do not reproduce without permission.

The post How much could 19th century nonfiction authors earn? appeared first on OUPblog.

By: Alice,

on 2/4/2013

Blog:

OUPblog

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

George W. Bush,

Current Affairs,

income,

taxpayers,

zelinsky,

Edward Zelinsky,

President Obama,

estate,

incomes,

*Featured,

origins of the ownership society,

Business & Economics,

How The Defined Contribution Paradigm Changed America,

American Taxpayer Relief Act of 2012,

capital gains tax,

high income taxpayers,

income tax law,

tax reductions,

dividends,

gains,

permanently,

Add a tag

By Edward Zelinsky

The American Taxpayer Relief Act of 2012 is widely understood as a victory for President Obama. However, the long-term story is more complicated than this. The Act in large measure confirms in bi-partisan fashion the tax-cutting priorities of George W. Bush.

In the Act, President Obama achieved his proclaimed goal of increasing income taxes on the country’s most affluent taxpayers through higher income tax rates and reduced deductions. The Act creates a new 39.5% income tax bracket for individuals with taxable incomes above $400,000 and for married couples filing jointly with taxable incomes above $450,000. It phases out personal exemptions for individuals with adjusted gross incomes over $250,000 and for married couples with adjusted gross incomes over $300,000. It also reduces itemized deductions for these affluent taxpayers.

For high income taxpayers, the Act increases the maximum capital gains tax rate from 15% to 20%. When combined with the new Medicare tax on investment income, this results in a combined tax of 23.8 % on capital gains for the highest income taxpayers.

It is thus unsurprising that the Act has been heralded as a triumph for Mr. Obama and his vision of a more progressive income tax law.

However, the reality is more complex than this. For the long run, the winner under the Act was Mr. Obama’s predecessor, George W. Bush. The Act, as it gave Mr. Obama some of what he wanted, also made permanent much of what Mr. Bush desired as a matter of tax policy. Indeed, as a result of the Act, federal taxes are in important measure now permanently at the lower levels where President Bush wanted them.

The vast majority of Americans are not affected by the Act’s changes for the highest income taxpayers. For most taxpayers, the Act thus permanently ratifies the lower federal income tax rates championed by Mr. Bush in 2001. Moreover, the Act confirms that corporate dividends will be taxed at lower capital gains rates rather than as ordinary income. True: capital gains rates are now higher for the most affluent of taxpayers as a result of the Act. However, even at these higher rates, taxing dividends as capital gains, rather than as regular income, significantly reduces the tax burden on such dividends.

Consider, moreover, the federal estate tax. When President Bush took office in 2001, the federal estate tax applied to estates over $675,000. That floor was scheduled to increase in stages to $1,000,000. The maximum federal estate tax rate was then 55%.

While President Bush did not succeed in abolishing the federal estate tax, the Act provides that federal estate taxation will only apply to estates over $5,000,000 adjusted for increases in the cost of living. For 2013, an estate must be over $5,250,000 to trigger federal estate taxation. When it applies, the estate tax will be levied at a flat rate of 40%.

In the area of tax policy, President Bush did not achieve all he sought. No president does. If we define success more realistically, the 2012 Act confirms President Bush’s triumph in permanently lowering federal income tax rates for most Americans, reducing the effective tax burden on corporate dividends, and significantly reducing the reach of the federal estate tax.

To some, these tax reductions are welcome restraints on the federal leviathan. To others, the Bush tax reductions, now permanent, regrettably hamper the federal fisc. What cannot be doubted is that the Internal Revenue Code we have today in large measure reflects the tax-cutting priorities of George W. Bush. In adopting the Act, a Democratic President and Senate, along with a Republican House, permanently confirmed much of these tax-reducing priorities.

Edward A. Zelinsky is the Morris and Annie Trachman Professor of Law at the Benjamin N. Cardozo School of Law of Yeshiva University. He is the author of The Origins of the Ownership Society: How The Defined Contribution Paradigm Changed America. His monthly column appears on the OUPblog.

Edward A. Zelinsky is the Morris and Annie Trachman Professor of Law at the Benjamin N. Cardozo School of Law of Yeshiva University. He is the author of The Origins of the Ownership Society: How The Defined Contribution Paradigm Changed America. His monthly column appears on the OUPblog.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only business and economics articles on OUPblog via email or RSS.

The post And the winner is… George W. Bush appeared first on OUPblog.

By: Lauren,

on 11/7/2011

Blog:

OUPblog

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

taxes,

Edward Zelinsky,

Thought Leaders,

Warren Buffett,

surcharge,

income tax,

incomes,

millionaires,

*Featured,

origins of the ownership society,

buffett,

Law & Politics,

Business & Economics,

fica,

buffett’s,

buffett rule,

federal tax rate,

Add a tag

By Edward Zelinsky

Although he had said it before, Warren Buffett struck a nerve with his most recent observation that his effective federal tax rate is lower than or equal to the effective federal tax rates of the other employees who work at Berkshire Hathaway’s Omaha office. Mr. Buffett’s observations have provoked extensive comments both from those supporting his position (e.g., President Obama) and those critical (e.g., the editorial writers of the Wall Street Journal).

In response to Mr. Buffett’s remarks, President Obama has promulgated what he calls “the Buffett Rule,” namely, that those making $1,000,000 or more per year should pay an effective federal tax rate higher than the effective rate paid by moderate income taxpayers. To implement this rule, Senate Majority Leader Harry Reid has proposed a 5.6% federal surtax on annual incomes over $1,000,000. The Congressional Research Service (CRS) has issued a report on the Buffett Rule. Deviating from Mr. Obama’s formulation of the Buffett rule, Mr. Buffett himself has indicated that he only favors higher income taxation for “the ultra rich,” a group which apparently consists of individuals earning substantially more than $1,000,000 annually.

The debate following Mr. Buffett’s comments has been spirited, but, for many, confusing. Here is my effort to clarify the facts and arguments.

1) FICA taxes are the predominant tax burden on most working Americans. As I discussed in last month’s blog, many working Americans pay little or no federal income taxes, but do pay significant FICA taxes to finance Social Security and Medicare. Democrats and Republicans alike have ignored this reality. Democrats prefer to ignore the heavy FICA tax burden on lower income Americans to preclude an honest discussion about the fairness of those taxes to younger Americans, even after considering the Social Security and Medicare benefits younger Americans may receive in the future. Republicans avoid the reality of FICA taxation because it undermines the mantra that half of all Americans pay no federal income tax. That statement is true but incomplete. Working Americans who don’t pay income taxes do pay significant FICA taxes. When Mr. Buffett compares his federal taxes to those paid by his secretary, it is the secretary’s FICA taxation which constitute much of the secretary’s obligation to the federal Treasury.

2) As to the taxation of the affluent, the real issue is the lower rates applicable to capital gains. The CRS estimates that approximately 1/4 of those with annual incomes over $1,000,000 violate the Buffett rule by paying federal taxes at effective rates equal to or lower than the effective tax rates of Americans of modest incomes. Besides the FICA taxes borne by working Americans, this phenomenon is caused by lower federal taxes on capital gains. Today, capital gains (including dividends) are generally taxed at a maximum federal tax rate of 15%. This is essentially the same as the combined employer-employee tax rate which applies under FICA to the first dollar of a working American’s wage income.

3) Millionaires pay higher taxes on their ordinary incomes. Mr. Buffett is evidently one of the millionaires whose income largely consists of lightly-taxed capital gains (including dividends). However, the bulk of those making more than $1,000,000 pay taxes at much higher rates than does Mr. Buffett because they earn ordinary incomes such as salaries and other business profits. These millionaires generally do not violate the Buffett rule since the federal inco

By: Lauren,

on 11/1/2010

Blog:

OUPblog

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

microsoft,

millionaire,

taxes,

Featured,

Finance,

taxpayers,

bill gates,

washington state,

billionaire,

Edward Zelinsky,

gates,

Gates Foundation,

foundation,

U.S. Treasury,

billionaires,

incomes,

millionaires,

exempt,

Law,

Business,

Add a tag

Dear Mr. Gates:

You have, by dint of your intelligence and sincerity, become a major spokesman for wealthy Americans calling for higher taxes. Since the nation’s budgetary problems will only be solved by combining spending reductions with tax increases, this is a compelling claim.

However, the devil, as they say, is in the details. Allow me to call three details to your attention:

1) Microsoft’s tax avoidance. Microsoft has become increasingly adept at parking its profits in low tax foreign jurisdictions, rather than paying U.S. taxes. After analyzing Microsoft’s financial statements, Tax Analysts’ Martin A. Sullivan recently concluded that Microsoft “has dramatically stepped up its efforts to take advantage of lax U.S. transfer pricing rules.” In lay terms, Microsoft is avoiding U.S. taxes by accounting maneuvers which shift its profits to low tax havens.

Of course, Microsoft is not alone in this behavior. However, Microsoft is the source of your family’s wealth and influence. I suggest that you start a campaign to press U.S. corporations to pay U.S. taxes and that you lead with Microsoft as the campaign’s first target.

2) Millionaires and billionaires are different. You are the leading proponent of the plan to establish an income tax in Washington State. The tax will be levied at a rate of 5% on annual incomes over $200,000 ($400,000 for couples). The rate will increase to 9% on annual incomes over $500,000 ($1,000,000 for couples).

Individuals earning these kinds of incomes are undoubtedly affluent. But few of them are software billionaires. Unfortunately, the Washington State levy will tax millionaires and billionaires at the same rates.

Many individuals triggering the first tier of the Washington income tax will be professionals like me. Many of the individuals triggering the higher tax level will be small businessmen and businesswomen. As to this latter group, the Washington tax will be among the nation’s highest. For these people, the tax will impose a noticeable burden and could lead to economic distortions such as a decision to leave Washington for a state with a low or no income tax.

It is neither fair nor efficient for the billionaires of Microsoft to pay the same marginal tax rates as these other taxpayers.

I suggest that you call for a third, substantially higher rate for the Washington State tax to apply to individuals such as you. The resulting revenues would permit a reduction of the rates applying to other, less affluent Washington State taxpayers.

3) The Gates Foundation is a tax shelter. The Gates Foundation does great work of which you and your family can be justifiably proud. But there is one thing the Gates Foundation doesn’t do: pay taxes.

You and your son have both been outspoken proponents of federal estate taxation. However, the resources you and he contribute to the Gates Foundation avoid such taxation. Moreover, the foundation, as a tax-exempt entity, pays no federal income tax.

I understand and applaud the charitable impulse which animates the Gates Foundation. My wife and I have established a private foundation in memory of our son though this fund is, needless to say, much smaller than the Gates Foundation.

It is, nevertheless, problematic to call for others to pay higher estate and income taxes while the Gates Foundation, one of the country’s largest, effectively shelters your and your son’s incomes and estates from the federal fisc.

I urge that the Gates Foundation annually and voluntarily