new posts in all blogs

Viewing: Blog Posts Tagged with: how to create, Most Recent at Top [Help]

Results 1 - 14 of 14

How to use this Page

You are viewing the most recent posts tagged with the words: how to create in the JacketFlap blog reader. What is a tag? Think of a tag as a keyword or category label. Tags can both help you find posts on JacketFlap.com as well as provide an easy way for you to "remember" and classify posts for later recall. Try adding a tag yourself by clicking "Add a tag" below a post's header. Scroll down through the list of Recent Posts in the left column and click on a post title that sounds interesting. You can view all posts from a specific blog by clicking the Blog name in the right column, or you can click a 'More Posts from this Blog' link in any individual post.

By:

Darcy Pattison,

on 11/6/2013

Blog:

Darcy Pattison's Revision Notes

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

revise,

dramatic,

stream of consciousness,

monologue,

how to create,

omniscience,

story,

novel,

point of view,

character,

Characters,

characterization,

Add a tag

Now available!

How does an author take a reader deeply into a character’s POV? By using direct interior monologue and a stream of consciousness techniques.

This is part 3 of a 3-part series on Point of View: Techniques for Getting Inside a Character’s Head. Read the whole series.

Outside

Outside/Inside

Inside

Going Inside a Character’s Head, Heart and Emotions

Omniscience.Jauss says, “In direct interior monologue, the character’s thoughts are not just ‘reflected,’ they are presented directly, without altering person or tense. As a result, the external narrator disappears, if only for a moment, and the character takes over as ‘narrator.’” (p. 51)

Omniscience.Jauss says, “In direct interior monologue, the character’s thoughts are not just ‘reflected,’ they are presented directly, without altering person or tense. As a result, the external narrator disappears, if only for a moment, and the character takes over as ‘narrator.’” (p. 51)

Here, “. . . the narrator is not consciously narrating.” In much of IVAN, he is consciously narrating the story. Sometimes, it might be hard to distinguish the difference because the character and narrator are the same, and it’s written in present tense (except when he is telling about the background of each animal). This closeness of the character and narrator is one reason to choose first-person, present tense. But there are still times when it is clear that IVAN is narrating his story.

But there also times when that narrator’s role is absent. In the “nine thousand eight hundred and seventy-six days” chapter, Ivan is worried about what Mack will do after the small elephant Ruby hits Mack with her trunk:

“Mack groans. He stumbles to his feet and hobbles off toward his office. Ruby watches him leave. I can’t read her expression. Is she afraid? Relieved? Proud?”

The last three questions remove the narrator-Ivan and give us what Ivan is thinking at the moment. The direct interior monologue gives the reader direct access to the character. With a third person narrator, those rhetorical questions might be indirect interior monologue; but here, because of the first person narration, it feels like direct interior monologue.

Or, in the “click” chapter, Ivan is about to be moved to a zoo:

The door to my cage is propped open. I can’t stop staring at it.

My door. Open.

The first two sentences still feel like a narrator is reporting. But “My door. Open.” feels like direct access to Ivan’s thought at that precise moment. He’s not looking back and reporting, but this is direct access to his thoughts.

A last technique for diving straight into a character’s head is stream-of-consciousness. Jauss says, “. . . unlike direct interior monologue, it presents those thoughts as they exist before the character’s mind has ‘edited’ them or arranged them into complete sentences.” (P. 54)

When Ivan is finally in a new home at a local zoo, he is allowed to venture outside for the first time. The “outside at last” chapter is stream-of-consciousness.

Sky.

Grass.

Tree.

Ant.

Stick.

Bird. . . .

Mine.

Mine.

Mine.

What the reader feels here is Ivan’s wonder at the great outdoors. It’s a direct expression of Ivan’s joy in being outside after decades of being caged. We are one with this great beast and it gives the reader joy to be there.

Or look at the “romance” chapter, where Ivan is courting another gorilla.

A final note: Sometimes, an author breaks the “fourth wall,” the “imaginary wall that separates us from the actors,” and speaks directly to the reader. This is technically a switch from 1st person POV to 2nd person POV. But it is very effective in IVAN in the second chapter, “names.” Here, Ivan acknowledges that you—the reader—are outside his cage, watching him. It was a stunning moment for me, as I read the story.

“I suppose you think gorillas can’t understand you. Of course, you also probably think we can’t walk upright.

Try knuckle walking for an hour. You tell me: which way is more fun?”

Do stories and novels have to stay in one point of view throughout an entire scene or chapter? No. Not if you are thinking about point of view as a technique to draw the reader close to a character or shove the reader away. You can push and pull as you need. You can push the reader a little way outside to protect his/her emotions from a distressing scene. Or you can pull them into the character’s head to create empathy or hatred. You can manipulate the reader and his/her emotions. It’s a different way of thinking about point of view. For me, it’s an important distinction because my stories have often gotten characterization comments such as , “I just don’t feel connected to the characters enough.” I think a mastery of Outside, Outside/Inside, and Inside point of view techniques holds a key to a stronger story.

In the end, it’s not about the labels we apply to this section or that section of a story. These techniques can blur, especially in a story like IVAN, written in first person, present tense. Instead, it’s about the reader identifying with the character in a deep enough way to be moved by the story. These techniques–such a different way to think about point of view!–are refreshing because they give us a way to gain control of another part of our story. These are what make novels better than movies. I’ve heard that many script-writers have trouble making the transition to novels and this is the precise place where the difficulty occurs. Unlike movies, novels go into a character’s head, heart and mind. And these point of view techniques are your road map to the reader’s head, heart and mind.

This has been part 1 of a 3-part series on Point of View: Techniques for Getting Inside a Character’s Head. Tomorrow, will be Inside: Deeply Inside a Character’s Head. Read the whole series

Outside

Outside/Inside

Inside

By:

Darcy Pattison,

on 11/5/2013

Blog:

Darcy Pattison's Revision Notes

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

story,

novel,

point of view,

character,

Characters,

characterization,

revise,

dramatic,

stream of consciousness,

monologue,

how to create,

omniscience,

Add a tag

Now available!

Partially Inside a Character’s Head: OUTSIDE AND INSIDE POV

How deeply does a story take the reader into the head of a character. Many discussions of point of view skim over the idea that POV can related to how close a reader is to a reader. But David Jauss says there are two points of view that allow narrators to be both inside and outside a character: omniscience and indirect interior monologue.

This is part 2 of a 3-part series on Point of View: Techniques for Getting Inside a Character’s Head. Here are links to parts 2 and 3.

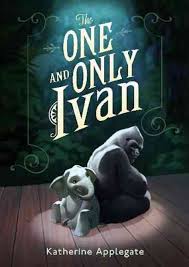

These posts are inspired by an essay by David Jauss, professor at the University of Arkansas-Little Rock, in his book, On Writing Fiction: Rethinking Conventional Wisdom About Craft. I am using Ivan, the One and Only, by Katherine Applegate, winner of the 2012 Newbery Award as the mentor text for the discussion.

Omniscience. Traditionally, “limited omniscience” means that the narrator is inside the head of only one character; “regular omniscience” means the narrator is inside the head of more than one character.

Omniscience. Traditionally, “limited omniscience” means that the narrator is inside the head of only one character; “regular omniscience” means the narrator is inside the head of more than one character.

I love Jauss’s comment: “I don’t believe dividing omniscience into ‘limited’ and regular’ tells us anything remotely useful. The technique in both cases is identical; it’s merely applied to a different number of characters.”

He spends time proving that regular omniscience never enters into the heart and mind of every character in a novel. A glance at Tolstoy’s WAR AND PEACE, with its myriad of characters is enough to convince me of this truth.

Rather, Jauss says the difference that matters here is that the omniscient POV uses the narrator’s language. This distinguishes it from indirect interior monologues, where the thoughts are given in the character’s language. This is a very different question about POV: is this story told in the narrator’s language or the character’s language?

In IVAN, this is an interesting distinction because Ivan is the narrator of this story; it’s told in his voice. But as a narrator, there are times when he drops into omniscient POV. In the “artists” chapter, Ivan reports:

“Mack soon realized that people will pay for a picture made by a gorilla, even if they don’t know what it is. Now I draw every day.”

Ivan tells the reader what Mack is thinking (“soon realized”) and even what those who purchase his art are thinking (“even if they don’t know what it is”). Then, he pulls back into a dramatic reporting of his daily actions. Notice, too, that he makes this switch from dramatic POV to omniscient POV within the space of one sentence. And the omniscient POV dips into two places in that sentence, too.

Because Mack is Ivan’s caretaker and has caused much of Ivan’s troubles, the reader needs to know something of Mack’s character. This inside/outside level is enough, though. The author has decided that a deep interior view of Mack’s life isn’t the focus of the story. It’s enough to get glimpses of his motivation by doing just a little ways into his head.

Indirect Interior Monologue

Another technique for the narrator and reader to be both inside and outside a character is indirect interior monologue. Here, Jauss says that the narrator “translates the character’s thoughts and feelings into his own language. “ (p. 45) The character’s interior thoughts aren’t given directly and verbatim. This is a subtle distinction, but an important one.

Interior indirect monologue usually involves two things: changing the tense of a person’s thoughts; and changing the person of the thought from first to third. This signals that the narrator is outside the character, reflecting upon the character’s thoughts or actions.

They are all waiting for the train. (dramatic)

They were all waiting reasonably for the train. (Inside, indirect interior monologue)

The word “reasonably” puts this into the head of the narrator, who is making a judgment call, interpreting the dramatic action.

Interior indirect monologue most often seen with a third-person narrator reflecting another character’s thoughts. But in Ivan, we have a first-person narrator. Applegate stays strictly inside Ivan’s head, except for a few passages where Ivan reports indirectly on another character’s thoughts. Because the passages are already in present tense, she doesn’t have that tense change to rely on.

Here’s a passage that could have been indirect interior monologue but Applegate won’t quite go there. Stella is an elephant in a cage close to Ivan.

“Slowly Stella makes her way up the rest of the ramp. It groans under her weight and I can tell how much she is hurting by the awkward way she moves.”

By adding “I can tell. . .” it stays firmly inside Ivan’s head. He tells us that this is true only because Ivan makes an observation. The story doesn’t dip into the interior of the other characters.

But there are tiny places where the interior dialogue peeks through. This from the “bad guys” chapter. Bob is Ivan’s dog friend; Not-Tag is a stuffed animal; and Mack is Ivan’s owner.

“Bob slips under Not-Tag. He prefers to keep a low profile around Mack.”

Ivan can only know that Bob “prefers” something, when he, as the narrator, dips into Bob’s thoughts.

But indirect interior monologue is also used by a first person narrator to report his/her prior thoughts. When the first person narrator tells a story about what happened in his past, he is both the actor in the story and the narrator of the story. Ivan tells the story of his capture by humans over the course of several short chapters. It begins in the “what they did” chapter:

“We were clinging to our mother, my sister and I, when the humans killed her.”

While Ivan’s story is most present tense, this is past tense because Ivan is reporting on prior events. Even here Applegate refuses to slip into interior indirect monologue. Instead, she just presents the facts in a dramatic manner and lets the reader imagine what Ivan felt. It’s interesting that withholding Ivan’s thoughts here evoke such an emotional response in the reader.

On the other hand, in “the grunt” chapter, Ivan tells about his family. Again, he is the narrator telling about a past event when he was a main character of the event:

“Oh, how I loved to play tag with my sister!”

This could be called direct interior thought, but because he’s narrating a past event, it’s indirect interior thought. Otherwise, he would say, “Oh, how I love to play tag with my sister!”

Or from the “vine” chapter, where Ivan talks about his thoughts after being captured by humans:

“Somehow I knew that in order to live, I had to let my old life die. But sister could not let go of our home. It held her like a vine, stretching across the miles, comforting, strangling.

We were still in our crate when she looked at me without seeing, and I knew that the vine had finally snapped.”

If this was direct interior, it would be:

“Somehow I know that in order to live, I must let my old life die.”

Applegate could have chosen to stay inside Ivan, but here, she pulls back so the reader isn’t fully inside this emotionally disturbing moment. She uses indirect interior monologue, instead of direct.

As Jauss says about a different passage, but it applies here, “This example also illustrates the extremely important but rarely acknowledged fact that narrators often shift point of view not only within a story or novel but also within a single paragraph.” (p.50)

This has been proclaimed a mistake in writing point of view, but Jauss says it’s a normal technique. We dip into Mack’s point of view, but then pull back to a dramatic statement about what Ivan is doing.

Indirect interior monologue often includes “rhetorical questions, exclamations, sentence fragments and associational leaps as well as diction appropriate to the character rather than the narrator. “ (p. 49) In one of my novels, I used a lot of rhetorical questions as a way to get into the character’s head and an editor complained about it. Now, that I know why I was using it (as a way to manipulate how close the reader was to the character), I could go back and use a variety of techniques. Knowledge of fiction techniques is freeing! Tomorrow, we’ll look at how to go deeply into a character’s head, heart and emotions.

This is part 1 of a 3-part series on Point of View: Techniques for Getting Inside a Character’s Head. Join us tomorrow for the final part of the series, Inside: Going Deep into a Character’s Head.

This has been part 2 of a 3-part series on Point of View: Techniques for Getting Inside a Character’s Head. Tomorrow, will be Inside: Deeply Inside a Character’s Head. Read the whole series.

Outside

Outside/Inside

Inside

By:

Darcy Pattison,

on 4/24/2013

Blog:

Darcy Pattison's Revision Notes

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

how to create,

fiction,

novel,

point of view,

creative writing,

character,

characters,

attitude,

prompts,

Add a tag

2013 GradeReading.NET Summer Reading Lists

Keep your students reading all summer! The lists for 2nd, 3rd and 4th, include 10 recommended fiction titles and 10 recommended nonfiction titles. Printed double-sided, these one-page flyers are perfect to hand out to students, teachers, or parents. Great for PTA meetings, have on hand in the library, or to send home with students for the summer. FREE Pdf or infographic jpeg.

See the Summer Lists Now!

You know you should try writing your story in first v. third point of view, but for some reason, you put it off. Why? Because you’ve gotten a first draft of a scene or chapter and you just want to keep going.

It’s exactly the feeling that elementary school children have: “Why do I have to revise?”

Your answer is straightforward: because you are a professional writer. Revising will help you write a book.

You must find the right way to tell this story. I often say that the purpose of a first draft is to find the story, but the purpose of all other drafts is to figure out the best way to TELL that story. Pros experiment, play, explore.

Here are some explorations of character that you can complete in an hour. Just set a time for 5-10 minutes and write something on each of these. If the prompt reveals nothing, drop it. But if it strikes a chord—keep going!

- 1st v. 3rd. Write a scene using first person point of view and then rewrite it using third. If you want to play with present tense, feel free. Play!

- Attitude. Choose a scene and look to see what attitude your main character has. Maybe, s/he comes in arrogant, sad, discouraged, or excited. At the top of your page/file, write the opposite attitude and write the scene again, working to make the character’s opposite attitude work.

- Setting. Choose a scene and change the setting. If it’s in the kitchen, send your characters on a picnic. If it’s set on a spaceship, move the story to a cruise ship on the Mediterranean.

- Write a Letter. Give your main character a reason to write a letter to someone. It could be written to a family member or to a Congressman. Let your character vent, rant and cry on paper.

- Put something in your character’s hand. Put a physical object in your character’s hand. Perhaps a mother goes into a grown son’s room and picks up his old baseball glove and sits in a rocking chair and oils the glove and remembers something important about her son. Or, a grandmother is in the kitchen and getting ready to cook and pulls out an iron skillet. Write a couple paragraphs or a scene putting the object in the forefront.

- Cubing is a way of exploring a topic by looking at it from different angles. I’ve chosen just four ways, but you can think of others.

- Describe. Using the character’s voice (your choice of POV, tense, etc) describe something important in your story. Repeat with a different POV, tense, etc. if you have time.

- Compare. Using the character’s voice, compare something in your story. Maybe you want to compare what the character thinks about his/her current situation with where s/he was ten days ago. Or compare two characters. Or compare today’s supper with yesterday’s supper. Any type of comparison that makes sense for your story is grist for this mill.

- Associate. When your character thinks of roses, what does s/he think? This prompt asks you to enter your character’s point of view and make some associations. While most of your writing in a scene should be pointed, there are places where you can slow down and give the reader a glimpse of how the character’s mind works. When faced with X, s/he thinks of Y or Z.

- Analyze. What will your character do next? Stop and let him/her analyze what has just happened, thinking about the ramifications of the actions or conversations. If s/he goes this direction, what will it mean for the rest of the story? What is an alternate direction and why should s/he choose that alternate? Analyze, then let the character decide on a plan of attack for the next section of the story.

Take the time to explore your story and your storytelling choices early in your drafting process. It will probably mean fewer drafts—and a stronger story. Great trade-offs for a mere hour of work.

Follow our Pinterest Boards

I learned that Sit-Coms just spit it out. On one episode of Everybody Loves Raymond, Raymond’s brother Robert comes over to take the kids to the zoo. Raymond realizes that the kids might even like Uncle Robert more than him. Robert actually spits it out: You’re not a good father.

Of course, in a sit-com, all you’ve got is the dialogue. Like movies, you can’t get in the characters’ heads, you only have dialogue and actions to make a point. Robert clearly expresses his opinion of Raymond’s parenting skills–in the dialogue.

Raymond, of course, retaliates and tells Robert that he needs to get a life.

Fast forward to the end: Raymond has had a successful (sorta) day at the zoo with the kids and comes home to find Robert in the hot tub with two hot chicks.

Robert: Looks like you are a good father.

Raymond: Looks like you got a life. I’d get in that hot tub with you, but I didn’t come prepared.

Robert: That’s OK, you can use my swim trunks, they are over there. (Beat. That means wait for the audience to get the joke and laugh and appreciate it.) Just kidding.

I learned that the emotional content in a sit-com is laid bare. Characters actually say what the theme of the story is. Here, it’s a two-fold question: Is Raymond a good father? Does Robert have a life outside his duties as uncle? The important moments along the character’s emotional arc are so obvious. And isn’t that nice for the writer? We don’t have to imply, infer, implicate. Just spit it out.

As a novelist, I know that I have more tools than a scriptwriter, so I can put some of the characters’ tensions, fears, and pains into interior dialogue, narrative sections and can use sensory details to fully flesh out a scene and create the right mood. But I’ve added a new tool: Just spit it out.

Timing is crucial. Above, I had the aside about the BEAT, the pause for the audience to get the joke. Sit-coms work because the actors and actresses have superb timing. One book on acting in sit-coms emphasizes the importance of the actor/actress following EXACTLY the script, especially in terms of punctuation. Where should the character hesitate, pause, speed up, scream, whisper–in short, the scriptwriter is allowed to direct the pacing and delivery of the dialogue.

I’ve taken a new look at my punctuation this week, with an eye to pacing the delivery of dialogue. Am I using silences, pauses, hesitations, stuttering, speeding up, etc. to create an extra layer of meaning, to make jokes work, or to characterize?

I am working on a series proposal and have been asked for a list of characters. Wow, what a lot you can learn from a list.

- Name them all. First, I created a list that just names the characters. It’s interesting to see the variety (or lack thereof) in just the names. For children’s books, I am careful to avoid using the cliched names and to include some names that could represent ethnic groups (of course, being careful not to be cliched with that, either). Did you notice the huge variety of names of competitors in the 2012 London Olympics? I was inspired to push past the usual when naming characters. Try some of these girl names: Soulmaz, Reem, Shaza, Mouni, Layes, Tomomi, and Aminata. Boy names: Alaaeldin, Arnaldo, Amir, Kanat, Raidel, Georgias, Kieron, and Idrissa.

- Write a paragraph about main characters. My next task was to write a paragraph or two about each of the main characters. One check of effective characterization that I like to use if to read ONLY the first five pages, turn over page five and write everything I know about a character from those pages (and ONLY those pages). That was telling! Of course, for this summary, I could add things from later, too. But I will go back and revisit those early pages to sharpen the characterization.

- Minor characters. These characters need to be individuals, too, and I found that I am weak sometimes on this level, too. I need to make sure that each one has a quirky trait, identifiable physical characteristic or unusual way of talking. For example, Freddy has the unusual skill of being able to cram 30 french fries into his mouth at one time. I need to give him a full mouth each time he tries to talk. Indeed, a couple of the minor characters were only a name–not a real character. It’s OK to have placeholders, but before I send this out again, I’ll flesh them out a tiny bit more, at least give them a character tag.

- Types of characters. This is a story set in a school, so I also looked at the type of characters I used. There are students, parents and teachers. Oops! I forgot to create a principal of the school! S/he can be a minor character, but s/he probably needs to be there in some capacity.

What characters have you inadvertently omitted?

I’ve written before about the importance of using strong body language for your characters. The September, 2011 Cosmopolitan magazine, featured an article by Mina Azodi on “Cool Mind Tricks that can Give you an Edge.” Really, she’s talking recent research on body language. Here are some extra body language tips to consider.

Give your character a pair of sunglasses. The classic gambit of hiding behind a pair of shades actually frees a person to do and say anything. With inhibitions lowered, look out. It often translates into selfish or hedonistic behavior.

Your character sits with one arm on a chair rest and the other draped along the chair’s back. Add an ankle crossed over the opposite knee. What do you have? Confidence. Only a confident character can pull off such an open, casual and yet commanding position.

Your character nods yes. Angela and Judd are about to explode at each other. What can prevent the relationship from self-destruction? A simple nod of the head tricks a person into being more agreeable, and stops the escalation of an argument. Bring the characters to the brink, then pause and let one of them do a simple head nod to turn the scene toward a resolution.

Your character washes his/her hands with soap. When Pilate washed his hands of Jesus death on the cross, he was practicing this body language technique. Studies show that when you make a decision, you are less likely to second-guess that decision if you wash your hands. Did Angela just lie to Judd? She’ll feel less guilty if she washes her hands. Even an antibacterial wipe works! So, after that argument when Angela just lied, send her to the kitchen to think about the relationship and let her wash away her worries.

Your character picks up and holds a heavy object, like a paperweight. Is your character considering something important, about to make a decision? People tend to give their opinion more weight when they are holding something like a heavy clipboard. In the midst of decision making, send Judd down to lift weights. It will make him more serious and it’s likely the decision will be a better one.

Your character presses up on the underside of a desktop or a table with his/her fingertips. Pressing up brings flexes the arm muscles you use to bring things closer to your body, which translates into more openness and creativity. Angela’s more likely to creatively solve a problem when she presses up with her fingertips. However, the opposite is also true: pressing down makes a person feel less accepting and more closed off. Press up and Angela gets creative about a problem; press down and she sulks.

Your female character hugs a guy. Angela hugs Judd and–what happens? When women smell a man’s hair or skin, they instantly feel more relaxed. She doesn’t need that glass of wine, she just needs a quick hug and whiff. And it doesn’t have to be a flame that she hugs, just a brother or father will do.

Your character takes a few steps backward. Stepping backwards seems to send your brain into problem-solving mode and you’ll be more likely to answer test questions with accuracy and speed. Angela and Judd fighting again (yes, fiction needs lots of conflict!)? This time, Judd takes a couple steps backward, away from Angela, which lets him see the big picture better and understand the correct next step for their relationship. In the end, it may send him into Angela’s arms, but he’s got to step backwards first in order to solve the problem.

Doodle! Wow, I am so glad to see this one because I always doodle. Turns out that doodling can actually increase your memory by about 30%. Scientists speculate that the drawings engage the area of the brain which might otherwise be used for daydreaming and zoning out. Keep part of your brain busy, so the rest can pay attention–nice.

Your character leans his/her upper body forward. Angela and Judd are discussing the possibility of getting married (I know, they argue so much, I am worried about them making it, too.) Scientists say that if you lean forward, it helps you visualize the future more vividly, so you’ll have an easier time planning. Angela leans forward and visualizes Prince Charming; Judd leans forward and Angela becomes the woman of his dreams. Together, leaning toward each other across the table, they might just imagine a future that will work.

Why X Heads are Better than I

guest post by Katy Duffield

We all know that writing is rewriting. As much as we’d like for it to be otherwise, early drafts just aren’t ready for prime time. It is imperative that we reread and cut, revise and rearrange, polish and restructure, and cut even more until our manuscripts are as strong as they can be. One of the best ways I’ve found to assist in the quest for the strongest possible manuscript is my writing group—or, in my case, my writing groups. If you know me, you know that I’m a strong proponent of the “two heads are better than one” theory. And even more “heads” are better still. And that’s just what writing groups can offer.

I Love These Gals!

I am a member of an online writing group that has been in existence for eight years. We originally met on author Verla Kay’s Children’s Writers Discussion Board—affectionately known as the “Blue Boards” (http://www.verlakay.com/boards/index.php). This particular group meets only online, through a dedicated Yahoo listserv group, and our writing runs the gamut: rhyming and non-rhyming picture books, middle grade and young adult novels (including verse novels), nonfiction, magazine writing, teacher’s guides and so on. And just as our writing varies, so do our geographical locations; we reside in Canada, Virginia, California, Missouri, Arkansas, and even Brazil.

When the group first formed, we followed a rotating schedule where one or two members would submit a story, chapter, or other piece of writing each week for the others to critique. Our schedule is less rigid now, as we currently submit only on an as-needed basis, but setting up a particular rotation can be a good idea. Just knowing that you have someone anxiously awaiting a new piece of work or a revision when your turn rolls around is a great incentive to keep writing. And the online format is wonderful because you can read and critique on your own schedule.

Back Row (l to r): Cassandra Reigel Whetstone, Sara Lewis Holmes, Anne Marie Pace, Alma Fullerton, DeAnn O'Toole, Loree Burns, Katy Duffield, Kristy Dempsey, Linda Urban. Front row: Kathy Erskine, Tanya Seale

Over the years, this particular group has morphed and changed. We’re no longer simply critique partners; we’re close friends. We no longer simply share our writing; we share our families, our worries, our joys and heartbreaks—we share our lives. We’ve been known to generate more than a thousand messages in a month! At this point, it’s as much a

support group as it is a critique group. It’s amazing to be a part of a like-minded group of people who understand the importance of celebrating the small victories and who understand the agonies that can be a big part of this business. I have no doubt that I have been richly blessed to find such an amazing group of women. A couple of years ago, we finally had the opportunity to meet in person at Boyd’s Mills for a Highlights Founder’s Retreat (where we happily added five new and wo

In our continuing quest to write 750 words per day for a month, today we will look at unlikeable main characters.

Which One is Unlovable? The Eye of the Beholder

Here’s the thing: readers need to LIKE your character. Why else would they spend hours walking in their shoes? But what if your character is in mental anguish, or like to hurt puppies, or is a jerk to every girl he dates? How do you get the reader on your side?

Donald Maass, in How to Write the Breakout Novel, says to make this type character self-aware. They know what they are doing is wrong, they acknowledge it. They take the sting out of the behavior by telling the reader they understand it is unacceptable. Nevertheless, they must do it. And of course, you’ll then add in the reasons why this behavior is reasonable.

The date jerk was dumped when he was 13 and has never gotten over it.

The guy in anguish is grieving over the loss of his family to a drunk driver. The guy who hurts puppies–oh, that’s a hard one! How WOULD you justify that? Oh, isn’t that the story, OF MICE AND MEN?

A second way to turn a jerk into a lovable character is to have someone demonstrate that they do indeed love him or her. Scarlett O’Hara is jealous, conniving and a drama queen. But the family’s nanny still loves her. Because the nanny loves her, we feel more tender toward Scarlett.

Today, write about an unlovable character.

- They must say, do and think awful things.

- Then, soften the character by having someone do a loving act toward them.

- Soften the character farther by having him or her acknowledge the errors of his or her ways.

Think like a writer: make me want to read about that unlovable character.

| |

NEW EBOOK

Available on

|

For more info, see

writeapicturebook.com

By:

Darcy Pattison,

on 8/23/2011

Blog:

Darcy Pattison's Revision Notes

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

character,

characters,

characterization,

mad,

anger,

emotion,

flat,

how to create,

round,

big actions,

Add a tag

Character Emotions MUST Spill Out into Big Actions

Characters, even supporting characters, should be bigger than life. No flat characters. Fiction demands round, “fleshed-out” characters. I’m working on a revision and I know this. Yet, when a friend read my revision, her response was that I needed big actions for my characters.

In the revision, I had noticed that the supporting character (Father) didn’t have much reaction to the main character (Laurel). I revised, adding in actions. But the actions were small: fist clenched, raising eyebrow, turning away.

Nothing wrong with those actions if Matt Damon was doing them on the big screen. There, the small actions would mean more. But think of him as Bourne and you’ll remember the BIG actions.

Revise for Emotions that Spill Out into Action

Revised: now, Father picks up a blanket and shakes it, snapping it up and down. He throws it onto a bed and when it falls off, he wads it up and throws it at the wall. It’s not the huge actions of an action-thriller, but in the context of the current scene, these are big actions. (Make sure you keep everything relative and in context!)

Even supporting characters need big actions. So, why didn’t I use them before? I think it’s because I’m a very restrained person myself. I keep a tight rein on emotions, not letting them spill out into big actions. That means for my characters, I need to push them to build emotions so strong that they MUST spill over into big actions.

And yes, the revision is much stronger. My early readers report that the Father is starting to come alive. Hello, Dad!

How Does Your Character Change?

You know your character must change somehow over the course of your novel. But how? And more than that, how do you sync the changes with the external plot? The middle of a novel can suffer from the dreaded “sagging middle” and it’s mainly because you don’t have a firm handle on the character’s inner arc and how it meshes with external events.

I’ve found three approaches to the inner arc, each trying to laying out how the character changes. While these overlap a lot, there are differences in how the emotional changes are approached.

Hero’s Journey: Quest for Inner Change

In the Hero’s Journey, laid out so well in Christopher Vogler’s book, The Writer’s Journey, a character receives a Call to Adventure that takes him/her out of the normal and ordinary world into a world where they must quest for something. One of the key moments in this paradigm is the Inmost Cave where the character faces his deepest fears.

In the Hero’s Journey, laid out so well in Christopher Vogler’s book, The Writer’s Journey, a character receives a Call to Adventure that takes him/her out of the normal and ordinary world into a world where they must quest for something. One of the key moments in this paradigm is the Inmost Cave where the character faces his deepest fears.

Melanie as an Example

So, we’ve got Melanie who wants more than anything else to get her mother’s approval, but can’t because her mom’s a chef and Melanie can’t cook worth a flip.

In the Hero’s Journey, Melanie might get a Call to Adventure: a challenge to create the world’s largest hot fudge sundae. Her darkest moment will come when she realizes Mom think’s she’s real goof-up and she’s not up to the task. Of course, she wants to give up, but somehow manages to rally (perhaps, recruiting friends to help, learning to make a sundae, etc.) and create something that makes Mom proud.

Iron Sharpens Iron – Friendships

As iron sharpens iron, so one man sharpens another. Proverbs 27:17

In this paradigm, two characters cross paths in Act 1 and usually hate each other, but Act 2 throws them into a situation where they must act together. Here, the characters’ strengths and weaknesses work to create change. It’s an up and down battle of learning to trust each other and ultimately find some sort of love, whether it’s platonic, romantic or maternal. Key moments are the midpoint when they totally lose faith in one another and a re-commitment to each other as they move from Act 2 to Act 3. Act 1 and 3 focus on the external story, while Act 2 follows how the friendship affects the characters.

For more on this paradigm, read, Emotional Structure: Creating the Story Beneath the Plot by Peter Dunne.

Back to Melanie:

Melanie agrees to participate in the Biggest Sundae Ever contest, but as the contest starts she’s assigned a dunce to work with, Phillip RunnyNose. They clash immediately and have different ideas on how to create the required masterpiece: Melanie wants total creative control, while Phillip wants to just take pictures of the masterpiece. During their practice run–about the middle of act 2–Phillip leaves the ice cream out to soften up, but it melts, ruining the prac

When you write kids’ books, there’s often a parent component. Duh. Kids have parents. So what?

Get Rid of Adults

One recommendation for dealing with parents is to get rid of them. Send them out of town for work; get rid of at least one parent through death, divorce or neglect; stick them in the background and barely mention them. There’s good reason to suggest getting rid of parents. After all, a main character MUST solve his/her own problems and a well-meaning parent could ruin your story.

Family Stories

But what if this is a family story? As I said last week, I’m reading through Please Understand Me II: Temperament, Character, Intelligence, a book about the Briggs-Meyers types of personalities and Chapter 8 was an amazing revelation. It’s about Parenting!

But what if this is a family story? As I said last week, I’m reading through Please Understand Me II: Temperament, Character, Intelligence, a book about the Briggs-Meyers types of personalities and Chapter 8 was an amazing revelation. It’s about Parenting!

Personality Type as a Child. It goes through an explanation of how a basic personality type would be played out as a child. An Idealist Child (NF, including INFT, INFP, ENFT, ENFP) would be soulful, emotional and self-examining.

Personality Type as a Parent. Likewise, the parenting style of the different types is explained. An Artisan Parent (SP, including ISPN, ESPN, ISPT, ESPT) has a hands-off style, letting kids learn lessons on their own.

Combination of Parent-Child. What happens when one personality style is in charge of another, like in the parent-child relationship? They might clash, or they might bring out the best in each other. For example an Artisan Parent (SP) and an Idealist (NF) kid is explained like this:

Although they can have some trouble understanding each other, Artisan parents can be valuable models for their Idealist children. NF kids tend to get lost in abstraction and a self-absorbed search for meanings and portents , and the SP’s warm embrace of immediacy can be an important lesson for them. p.277

You may not want to be so strict in figuring out what personality type the parents and kids actually are (though it does help with character development). But it’s interesting reading through the different types of interaction between kids/parents. Of course, this is the “nature” part of the equation and you’ll want to add the “nurture” part through your story.

Personally, I try to get rid of parents. I agree that’s best. But sometimes–often, for me–the story is partly ABOUT that parent-child relationship. Especially for middle grade novels, parents and a kid’s relationship to them is extremely important. In those cases, this is a good resource for figuring out where the conflicts might lie and how to exploit the conflict for an exciting story.

Develop Your Character Inside and Outside

I’m working on a revision of an older story and am finding that my character is flat, lacking emotion.

Here’s what should happen: action, reaction, thought and/or emotion.

Here’s what is happening: action, reaction.

Of course, there’s lots of variation and times when either might be appropriate. But overwhelming, I’m finding that I try to imply the emotion by the reaction, but it’s not always working.

There’s this tension in writing between Telling and Show-don’t-Tell.

Telling

The tendency is to tell: he was upset.

The tendency is to tell: he was upset.

This type storytelling was popular before the invention of the modern novel, when storytellers created as much by their own voice and body language as anything.

The storytelling mode allows you to tell something and leave it at that. Listeners expected little else.

Show-don’t-Tell.

But with the novel, we are able to delve deeply into a characters thoughts, emotions, psyche. That’s why novels will never be replaced by film, because you can’t go deeply inside a character in any other way. Telling may still be used in bits and pieces, to summarize unimportant parts of the story.

But now, we expect thought and emotions to be forefront. Even more than that, though, we expect novels to be full of action and for that action to demonstrate the emotion/thought, so there isn’t so much telling going on.

Novels, then, go deeper into story by delving into the thought and emotions of a character; but also, by demonstrating those thoughts and emotions with concrete actions. It’s the concrete actions that create the Show-don’t-tell parts of storytelling.

Full Zoom: Inside and Outside

One way to think about it is that a scene is where the “narrative camera of words” zooms in. You get the full sensory details of the story situation and full details of character emotions/thoughts. In other words, the inside and outside of the story are in full zoom.

For sensory details, you must fully imagine being the character in this situation and what they would see, hear, smell, touch and taste. For emotions, we should know intimately what s/he is going through.

For me, it’s not Show-don’t-Tell; instead, I like Show-then-tell-some.

Mini-Conflicts Help Characters Stand Out

For my WIP, I’m spending the week fleshing out characters.

I”ve written about characters many times.

Here’s a Character Checklist, and 15 Days to a Stronger Character, and many other posts on character.

At this stage in character development, I’m mostly concerned with creating an interesting mix. For this story, there’s a crowd of characters which could get confusing for the reader unless each character is, well, a character! Unique. Compelling.

They must be different in at least these ways:

Description. I need a wide variety from fat to anorexic, tall to short, white to black, and young to old. Beyond that, there are so many variations! Hair can be wild or tame, big or missing.

Eyebrows fascinate me: drawn on or so hairy that they grow together in the middle.

Teeth: laser white, yellow, rotten, dentures, cracked, gaps.

Speech: With a background in speech pathology, I pay attention to this one for sure. I try not to put stuttering in too much (which means I never allow myself to do that for fear of doing it too much). Accents are a way to distinguish someone. Dialects are fascinating to study, for example the difference between Bostonians and New Orleans residents.

Movement: Those teens who sag&bag, walk with one hand on their waist band, hitching up the shorts/pants every other step. (Watch Pants on the Ground – the man who inspired a surge in the belt market.) Something like that, tied to the unique clothing style is what I’m looking for.

Create Mini-Conflicts

Of course, there are other ways, but you get the idea. What I’m especially looking for is the interaction between characters and their descriptions. For example, if there’s a sag&bag teen, there needs to be another character who despises that type of dress; and of course, those two characters need to come into direct conflict.

I’m matching up the characters for mini-conflicts like this. They won’t be the main plot, but will add comic relief, extra bits of tension, and variety to the novel. Doing this at this early stage will build in more potential, more material to work with as I start the first draft.

How do you make your characters stand out?

PR Notes Question of the Week

If you didn’t see Sunday’s post, I’ve asked a question about book promotion: If you had $1000 to spend on book promotion, how would you spend it? I’d love to hear a wide variety of responses this week. Please comment here.

4 Stages of Character Development

When you write a first draft, there are really two novels at that point. There’s the one on the paper and there’s the one in your head and they are not the same.

I know this. But I’m experiencing it again as I’m working through this revision. In order to put on paper what is in my head, I’ve had to pay attention to feedback.

Blurry Characters

http://www.flickr.com/photos/hugovk/217155496/ My first feedback told me that my characters weren’t understood. Readers didn’t understand motivations or relationships. I worked on that by checking each scene to make sure the characters were active and the scenes goals were clear. Sometimes, I found that my main character was just an observer and had to give him a more active role. But usually, this did little to help.

Confusing Characters. The second round of feedback told me the same thing: my readers were confused. Here’s the problem: I thought that readers would understand relationships from implications in the text. But that was making them work too hard; they lost confidence in my storytelling. I realized that I had to lay it all out there, in other words, put it on the page.

Now, this does NOT mean that I put in the whole kitchen sink. No. I didn’t want to overwhelm readers with backstory. But naming a relationship was OK: “she’s my almost-adoptive-mother.” The reader still doesn’t know all of what that “almost” means but at least there’s now a frame of reference.

For the secondary character, I added a tiny bit of flashback, only 3-4 lines. It’s active, unusual, with good segues in and out of it. I almost want to take it out, because I don’t like backstory in the first chapter. But I think it’s crucial for the reader to understand the nature of what this character faces.

Deeper Characters. Finally, this third time around, my reader says my characters are deeper, motivations are clear and I’ve created great sympathy for the characters’ plight. Now, I’m just inconsistent.

Inconsistent Characters. My job on the next pass was to make sure the characters’ voices stayed consistent, the characters didn’t do or say anything that was out of character for their age or situation, and that the story itself remained consistent in tone and voice.

Exactly What I Envisioned. Well, almost, anyway. Nothing is set in stone yet, but I’m pretty pleased with how these characters are behaving right now. Pleased enough to move on and not bother my readers with this section again, but wait until there’s a whole revised novel to read.

Do your characters progress through similar stages? Blurry, confusing, deeper, inconsistent, exactly what I envisioned. Notice what was needed at each point: feedback. I only knew how well I was doing by checking in with a reader. Sometimes, especially in the early chapters, I need several rounds of feedback with my readers to make sure I’m making the needed changes. Now, with these chapters as my benchmark, I’m hoping to progress without so much feedback.

How would you describe your character’s progression through drafts? What feeds your revision cycle?

Related posts: - Opening Chapters

- Listen

- Character Bait

|

Omniscience.Jauss says, “In direct interior monologue, the character’s thoughts are not just ‘reflected,’ they are presented directly, without altering person or tense. As a result, the external narrator disappears, if only for a moment, and the character takes over as ‘narrator.’” (p. 51)

Omniscience.Jauss says, “In direct interior monologue, the character’s thoughts are not just ‘reflected,’ they are presented directly, without altering person or tense. As a result, the external narrator disappears, if only for a moment, and the character takes over as ‘narrator.’” (p. 51)

Keep your students reading all summer! The lists for 2nd, 3rd and 4th, include 10 recommended fiction titles and 10 recommended nonfiction titles. Printed double-sided, these one-page flyers are perfect to hand out to students, teachers, or parents. Great for PTA meetings, have on hand in the library, or to send home with students for the summer. FREE Pdf or infographic jpeg.

Keep your students reading all summer! The lists for 2nd, 3rd and 4th, include 10 recommended fiction titles and 10 recommended nonfiction titles. Printed double-sided, these one-page flyers are perfect to hand out to students, teachers, or parents. Great for PTA meetings, have on hand in the library, or to send home with students for the summer. FREE Pdf or infographic jpeg.