new posts in all blogs

Viewing: Blog Posts Tagged with: Alternative Plots, Most Recent at Top [Help]

Results 1 - 7 of 7

How to use this Page

You are viewing the most recent posts tagged with the words: Alternative Plots in the JacketFlap blog reader. What is a tag? Think of a tag as a keyword or category label. Tags can both help you find posts on JacketFlap.com as well as provide an easy way for you to "remember" and classify posts for later recall. Try adding a tag yourself by clicking "Add a tag" below a post's header. Scroll down through the list of Recent Posts in the left column and click on a post title that sounds interesting. You can view all posts from a specific blog by clicking the Blog name in the right column, or you can click a 'More Posts from this Blog' link in any individual post.

By: Ingrid Sundberg,

on 8/8/2013

Blog:

Ingrid's Notes

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

Writing Craft,

Structure,

Story Structure,

Plot Structure,

Novel Structure,

Three Act Structure,

The Hero's Journey,

Story Design,

Organic Architecture,

Alternative Plots,

Alternative Structures,

Designing Principle,

Classical Design,

Add a tag

I want to thank everyone for reading my Organic Architecture Series! I realize this was a long series with lots of posts. The following are the links to all the different articles. Feel free to bookmark this page for easy reference!

I want to thank everyone for reading my Organic Architecture Series! I realize this was a long series with lots of posts. The following are the links to all the different articles. Feel free to bookmark this page for easy reference!

Happy plotting, structuring, and designing, everyone!

Organic Architecture Series:

Classic Design and Arch Plot:

Alternative Plots:

Alternative Structures:

Designing Principle:

Full Bibliography for this Series:

Alderson, Martha. The Plot Whisperer: Secrets of Story Structure Any Writer Can Master. New York: Adams Media, 2011.

Anderson, Tobin. “Theories of Plot and Narrative.” Faculty Lecture. Vermont College of Fine Arts, Montpelier, VT. July 2008.

Bayerl, Katie. “Must We All Be Heroes? Crafting Alternatives to the Hero’s Journey in YA Fiction.” Critical Thesis. Vermont College of Fine Arts, 2009.

Bayerl, Katie. “Must We All Be Heroes? Crafting Alternatives to the Hero’s Journey in YA Fiction.” Graduate Lecture. Vermont College of Fine Arts, Montepelier, VT. July 2009.

Bechard, Margaret. “How I Learned to Stop Worrying and Love Plot.” Faculty Lecture. Vermont College of Fine Arts, Montpelier, VT. Jan 2008.

Berg, Charles Ramirez. “A Taxonomy of Alternative Plots in Recent Films: Classifying the ‘Tarantino Effect.’” Film Criticism, Vol. 31, Issue 1-2, 5-57, 22 Sept 2006. Ebsco Host. Web. 6 May 2011.

Burroway, Janet. Writing Fiction: A Guide to Narative Craft. 8th Edition. New York: Longman, 2011.

Campbell, Joseph. The Hero with a Thousand Faces. Second Edition. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1968.

Campbell, Patty. “The Sand in the Oyster: Vetting the Verse Novel.” The Horn Book Magazine. Sept.-Oct.2004: 611-616.

Capetta, Amy Rose. “Can’t Fight This Feeling: Figuring out Catharsis and the Right One for Your Story.” Graduate Lecture. Vermont College of Fine Arts, Montepelier, VT. Jan 2012.

Carver, Renee. “Cumulative Tales Primary Lesson Plan.” Primary School. 9 Mar. 2009. Web. 31 Aug 2012.

Chapman, Harvey. “Not Your Typical Plot Diagram.” Novel Writing Help. 2008-2012. Web. 6 Oct. 2012.

Chea, Stephenson. “What’s the Difference Between Plot and Structure.” Associated Content. 16 Feb. 2010. Web. 7 May 2011.

Doan, Lisa. “Plot Structure: The Same Old Story Since Time Began?” Critical Essay. Vermont College of Fine Arts, 2006.

Field, Syd. Screenplay: The Foundations of Screenwriting. Revised ed. New York: Delta, 2005.

Fletcher, Susan. “Structure as Genesis.” Faculty Lecture. Vermont College of Fine Arts, Montpelier, VT. July 2012.

Forster, E.M. Aspects of the Novel. New York: Harcourt Inc., 1927.

Gardner, John. The Art of Fiction. New York: Vintage Books, 1983.

Gulino, Paul. Screenwriting: The Sequence Approach. New York: Continuum, 2004.

Hauge, Michael. Writing Screenplays That Sell. New York: Collins Reference, 2001.

Hawes, Louise. “Desire Is the Cause of All Plot.” Faculty Lecture. Vermont College of Fine Arts, Montpelier, VT. July 2008.

Kalmar, Daphne. “The Short Story Cycle: A Sculptural Aesthetic.” Critical Thesis, Vermont College of Fine Arts, 2009.

Kaufman, Charlie. “Charlie Kaufman: BAFTA Screenwriting Lecture Transcript.” BAFTA Guru. British Academy of Film and Television Arts. 30 Sept. 2011. Web. 18 Aug. 2012.

Larios, Julie. “Once or Twice Upon a Time or Two: Thoughts on Revisionist Fairy Tales.” Faculty Lecture. Vermont College of Fine Arts, Montpelier, VT. Jan 2010.

Layne, Ron and Rick Lewis. “Plot, Theme, the Narrative Arc, and Narrative Patterns.” English and Humanities Department. Sandhill Community College. 11 Sept, 2009. Web. 7 May 2011.

Lefer, Diane. “Breaking the Rules of Story Structure.” Words Overflown by Stars. Ed. David Jauss, Cincinnati: Writer’s Digest Books, 2009. 62-69.

Marks, Dara. Inside Story: The Power of the Transformational Arc. Ojai: Three Mountain Press, 2007. McKee, Robert. Story: Substance, Structure, Style and the Principles of Screenwriting. New York: IT Books, 1997.

McManus, Barbara F. Tools for Analyzing Prose Fiction. College of New Rochelle, Oct. 1998. Web. 11 Sept. 2012.

Schmidt, Victoria Lynn. Story Structure Architect. Cincinnati: Writer’s Digest Books, 2005.

Sibson, Laura. “Structure Serving Story: A Discussion of Alternating Narrators in Today’s Fiction.” Graduate Lecture. Vermont College of Fine Arts, Montpelier, VT. July 2012.

Snyder, Blake. Save the Cat: The Last Book on Screenwriting You’ll Ever Need. Studio City: Michael Wiese Productions, 2005.

Tanaka, Shelley. “Books from Away: Considering Children’s Writers from Around the World.” Faculty Lecture. Vermont College of Fine Arts, Montpelier, VT. Jan 2010.

Tobias, Ron. Twenty Master Plots: And How to Build Them. Cincinnati: Writer’s Digest Books, 1993.

Truby, John. The Anatomy of Story: 22 Steps to Becoming a Master Story- teller. New York: Faber and Faber Inc., 2007.

TV Tropes. Three Act Structure. TV Tropes Foundation, 26 Dec. 2011. Web. 11. Sept. 2012.

Vogler, Christopher. The Writer’s Journey: Mythic Structure for Writers. 2nd Edition. Studio City: Michael Wiese Productions, 1998.

Williams, Stanley D. The Moral Premise. Studio City: Michael Wiese Productions, 2006.

By: Ingrid Sundberg,

on 8/8/2013

Blog:

Ingrid's Notes

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

Writing Craft,

Structure,

Story Structure,

Plot Structure,

Novel Structure,

Three Act Structure,

The Hero's Journey,

Story Design,

Organic Architecture,

Alternative Plots,

Alternative Structures,

Designing Principle,

Classical Design,

Add a tag

I want to thank everyone for reading my Organic Architecture Series! I realize this was a long series with lots of posts. The following are the links to all the different articles. Feel free to bookmark this page for easy reference!

I want to thank everyone for reading my Organic Architecture Series! I realize this was a long series with lots of posts. The following are the links to all the different articles. Feel free to bookmark this page for easy reference!

Happy plotting, structuring, and designing, everyone!

Organic Architecture Series:

Classic Design and Arch Plot:

Alternative Plots:

Alternative Structures:

Designing Principle:

Full Bibliography for this Series:

Alderson, Martha. The Plot Whisperer: Secrets of Story Structure Any Writer Can Master. New York: Adams Media, 2011.

Anderson, Tobin. “Theories of Plot and Narrative.” Faculty Lecture. Vermont College of Fine Arts, Montpelier, VT. July 2008.

Bayerl, Katie. “Must We All Be Heroes? Crafting Alternatives to the Hero’s Journey in YA Fiction.” Critical Thesis. Vermont College of Fine Arts, 2009.

Bayerl, Katie. “Must We All Be Heroes? Crafting Alternatives to the Hero’s Journey in YA Fiction.” Graduate Lecture. Vermont College of Fine Arts, Montepelier, VT. July 2009.

Bechard, Margaret. “How I Learned to Stop Worrying and Love Plot.” Faculty Lecture. Vermont College of Fine Arts, Montpelier, VT. Jan 2008.

Berg, Charles Ramirez. “A Taxonomy of Alternative Plots in Recent Films: Classifying the ‘Tarantino Effect.’” Film Criticism, Vol. 31, Issue 1-2, 5-57, 22 Sept 2006. Ebsco Host. Web. 6 May 2011.

Burroway, Janet. Writing Fiction: A Guide to Narative Craft. 8th Edition. New York: Longman, 2011.

Campbell, Joseph. The Hero with a Thousand Faces. Second Edition. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1968.

Campbell, Patty. “The Sand in the Oyster: Vetting the Verse Novel.” The Horn Book Magazine. Sept.-Oct.2004: 611-616.

Capetta, Amy Rose. “Can’t Fight This Feeling: Figuring out Catharsis and the Right One for Your Story.” Graduate Lecture. Vermont College of Fine Arts, Montepelier, VT. Jan 2012.

Carver, Renee. “Cumulative Tales Primary Lesson Plan.” Primary School. 9 Mar. 2009. Web. 31 Aug 2012.

Chapman, Harvey. “Not Your Typical Plot Diagram.” Novel Writing Help. 2008-2012. Web. 6 Oct. 2012.

Chea, Stephenson. “What’s the Difference Between Plot and Structure.” Associated Content. 16 Feb. 2010. Web. 7 May 2011.

Doan, Lisa. “Plot Structure: The Same Old Story Since Time Began?” Critical Essay. Vermont College of Fine Arts, 2006.

Field, Syd. Screenplay: The Foundations of Screenwriting. Revised ed. New York: Delta, 2005.

Fletcher, Susan. “Structure as Genesis.” Faculty Lecture. Vermont College of Fine Arts, Montpelier, VT. July 2012.

Forster, E.M. Aspects of the Novel. New York: Harcourt Inc., 1927.

Gardner, John. The Art of Fiction. New York: Vintage Books, 1983.

Gulino, Paul. Screenwriting: The Sequence Approach. New York: Continuum, 2004.

Hauge, Michael. Writing Screenplays That Sell. New York: Collins Reference, 2001.

Hawes, Louise. “Desire Is the Cause of All Plot.” Faculty Lecture. Vermont College of Fine Arts, Montpelier, VT. July 2008.

Kalmar, Daphne. “The Short Story Cycle: A Sculptural Aesthetic.” Critical Thesis, Vermont College of Fine Arts, 2009.

Kaufman, Charlie. “Charlie Kaufman: BAFTA Screenwriting Lecture Transcript.” BAFTA Guru. British Academy of Film and Television Arts. 30 Sept. 2011. Web. 18 Aug. 2012.

Larios, Julie. “Once or Twice Upon a Time or Two: Thoughts on Revisionist Fairy Tales.” Faculty Lecture. Vermont College of Fine Arts, Montpelier, VT. Jan 2010.

Layne, Ron and Rick Lewis. “Plot, Theme, the Narrative Arc, and Narrative Patterns.” English and Humanities Department. Sandhill Community College. 11 Sept, 2009. Web. 7 May 2011.

Lefer, Diane. “Breaking the Rules of Story Structure.” Words Overflown by Stars. Ed. David Jauss, Cincinnati: Writer’s Digest Books, 2009. 62-69.

Marks, Dara. Inside Story: The Power of the Transformational Arc. Ojai: Three Mountain Press, 2007. McKee, Robert. Story: Substance, Structure, Style and the Principles of Screenwriting. New York: IT Books, 1997.

McManus, Barbara F. Tools for Analyzing Prose Fiction. College of New Rochelle, Oct. 1998. Web. 11 Sept. 2012.

Schmidt, Victoria Lynn. Story Structure Architect. Cincinnati: Writer’s Digest Books, 2005.

Sibson, Laura. “Structure Serving Story: A Discussion of Alternating Narrators in Today’s Fiction.” Graduate Lecture. Vermont College of Fine Arts, Montpelier, VT. July 2012.

Snyder, Blake. Save the Cat: The Last Book on Screenwriting You’ll Ever Need. Studio City: Michael Wiese Productions, 2005.

Tanaka, Shelley. “Books from Away: Considering Children’s Writers from Around the World.” Faculty Lecture. Vermont College of Fine Arts, Montpelier, VT. Jan 2010.

Tobias, Ron. Twenty Master Plots: And How to Build Them. Cincinnati: Writer’s Digest Books, 1993.

Truby, John. The Anatomy of Story: 22 Steps to Becoming a Master Story- teller. New York: Faber and Faber Inc., 2007.

TV Tropes. Three Act Structure. TV Tropes Foundation, 26 Dec. 2011. Web. 11. Sept. 2012.

Vogler, Christopher. The Writer’s Journey: Mythic Structure for Writers. 2nd Edition. Studio City: Michael Wiese Productions, 1998.

Williams, Stanley D. The Moral Premise. Studio City: Michael Wiese Productions, 2006.

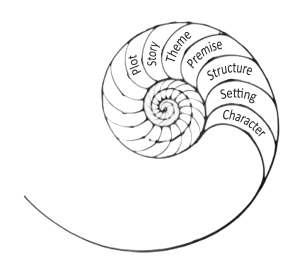

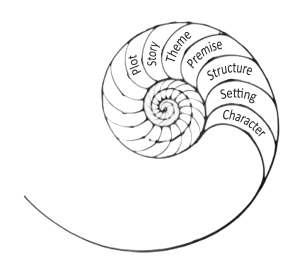

I’m my previous posts I’ve given you a pandora’s box of alternative plots (Alt. Plots Part 1 and Alt. Plots Part 2) as well as alternative structures (Alt. Structures Part 1 and Alt. Structures Part 2). And we ought to take classic design, the hero’s journey, and three act structure and throw them in that box as well.

But how do we use these?

How do we incorporate them into our writing process in a way that is organic? How do we make sure they come naturally from the story itself without becoming a dead-in-the-water template?

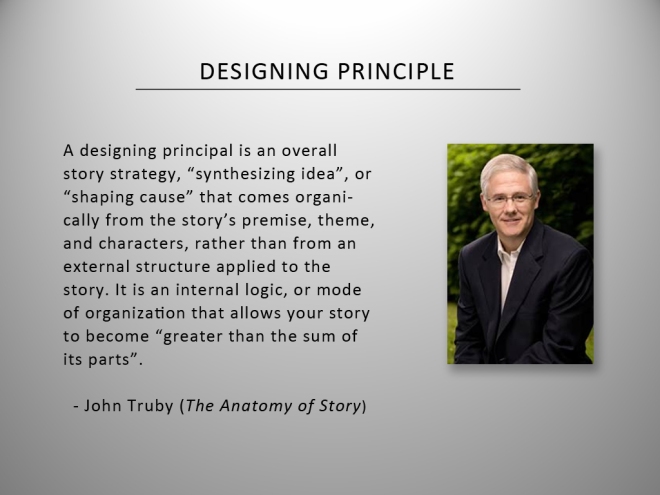

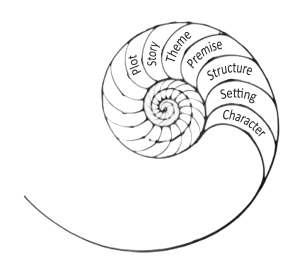

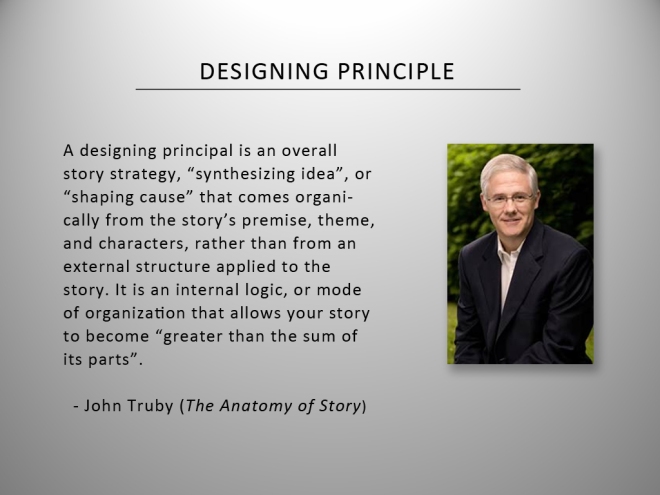

John Truby suggests that the best way to do this not through an external structure, but to look inside the work for an inherent designing principal. Truby is a little abstract in his definition of a designing principal, so here’s my cobbled-together version from what he says in the Anatomy of Story:

Does that sound like a bunch of writerly-MFA-mumbo jumbo? Let me give you some examples to help us understand the concept.

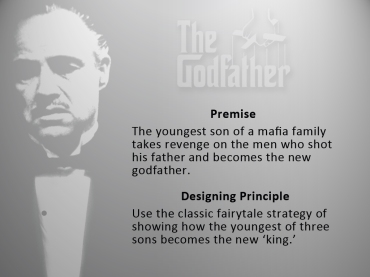

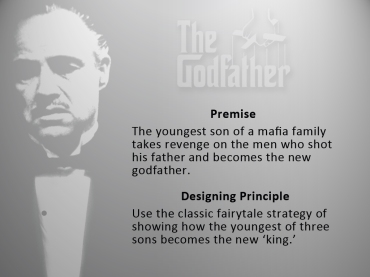

In the film The Godfather, the premise is: The youngest son of a Mafia family takes revenge on the men who shot his father and becomes the new Godfather. The idea of a designing principal is to find something that derives from that premise and those characters which adds a new layer of meaning, giving the story its originality, and acts as a guide for the writing process.

According to Truby, the designing principal of The Godfather is: “Use the classic fairy tale strategy of showing how the youngest of three sons becomes the new ‘king.’” With this underlying design the story is no longer generically about the mafia or revenge. Through the use of a fairy tale trope the story becomes elevated to one of legend. The fairy tale offers the writer a basic scaffolding for plot structure and there’s opportunity for thematic comparisons between the original story and its re-telling.

According to Truby, the designing principal of The Godfather is: “Use the classic fairy tale strategy of showing how the youngest of three sons becomes the new ‘king.’” With this underlying design the story is no longer generically about the mafia or revenge. Through the use of a fairy tale trope the story becomes elevated to one of legend. The fairy tale offers the writer a basic scaffolding for plot structure and there’s opportunity for thematic comparisons between the original story and its re-telling.

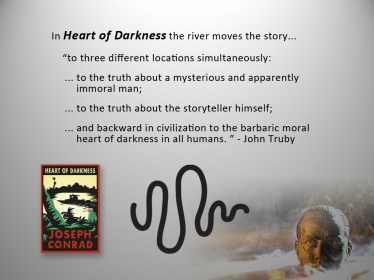

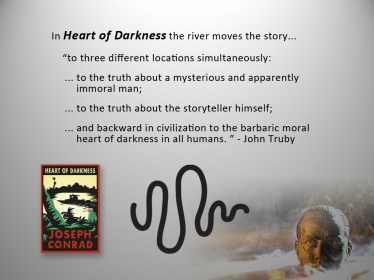

Another example is the use of a traveling metaphor such as a river. In Heart of Darkness, the protagonist, Marlow, is taking a boat ride up the river and progressing deeper and deeper into the jungle. The river is a designing principle for both structure and metaphor, moving the story into “three different locations simultaneously: to the truth about a mysterious and apparently immoral man” who Marlow is going up the river to find, providing plot structure for the external story. “To the truth about the storyteller himself;” a metaphor for the internal emotional story as the protagonist goes deeper into his own psyche. And it moves us “backward in civilization to the barbaric moral heart of darkness in all humans,” the novel’s underlying theme. The traveling metaphor contains the external story, the internal story, and the theme. No wonder this book is a classic.

There is no one way to create a designing principal, there are hundreds of them, and the one that is right for your story only you can find. But I’ve noticed certain “categories” if you will, certain patterns that designing principals sometimes fall under. The execution of each is unique to the themes and characters of each book, but I want to present the list I’ve generated thus far, as a jumping off point. My goal is to further illustrate this concept and to help you think about what might be the designing principal of your book.

There is no one way to create a designing principal, there are hundreds of them, and the one that is right for your story only you can find. But I’ve noticed certain “categories” if you will, certain patterns that designing principals sometimes fall under. The execution of each is unique to the themes and characters of each book, but I want to present the list I’ve generated thus far, as a jumping off point. My goal is to further illustrate this concept and to help you think about what might be the designing principal of your book.

I have six categories that I will discuss in my next posts:

1. A Character’s Mental State

2. Setting and Environment

3. Time

3. Community

4. Fairy Tales, Myth and Parallel Stories

6. Storyteller

Read more about John Truby’s concept of a designing principal on pages 25-29 of The Anatomy of Story.

Thanks for coming back to learn more about alternative plots!

Last week in Part 1, I covered mini-plot, daisy chain plot, cautionary tale plot, and ensemble plot. Today we’re going to continue to push the boundaries of arch plot and the hero’s journey by taking a look at along-for-the-ride plot, symbolic juxtaposition plot, repeated event plot, and repeated action plot. Again, I’ve termed an alternative plot as one that doesn’t have a hero (as defined by the hero’s journey), one that lacks a specific goal, or one that does not use traditional cause-and-effect as its connective tissue.

ALONG FOR THE RIDE PLOT

ALONG FOR THE RIDE PLOT

In the Along for the Ride plot there isn’t an active protagonist. Instead a secondary character drives the action and the protagonist is along for the ride. Often there’s still a change in the protagonist, showing that we don’t always have to be active goal-seekers for an event or person to incite personal growth.

- Book Examples: Looking for Alaska (Green), What I Saw and How I Lied (Blundell), Rebecca (Maurier).

SYMBOLIC JUXTAPOSITION PLOT (Also known as: Thematic Plot, Intellectual Plot, Anti-Plot, Existential Plot)

SYMBOLIC JUXTAPOSITION PLOT (Also known as: Thematic Plot, Intellectual Plot, Anti-Plot, Existential Plot)

In the symbolic juxtaposition plot the reader should be prepared for a more intellectual experience. Instead of traditional cause-and-effect, this plot uses themes, ideas, images, and concepts to connect scenes and sequences with meaning. It’s a more argumentative plot development where X doesn’t cause Y, but X is in a symbolic relationship to Y.

- Film Examples: Life in a Day, The Tree of Life, The Thin Red Line, Chunking Express, Waking Life.

- Book Examples: Einstein’s Dreams (Lightman), Criss Cross (Perkins).

REPEATED EVENT PLOT

REPEATED EVENT PLOT

In classical narrative, the same event is never shown twice. In this plot type, however, one event repeats several times throughout the story, but each re-telling usually offers a new perspective. Multiple characters are used to show that there is more than one version of the truth.

- Film Examples: Vantage Point, Hero, He Loves Me…He Loves Me Not.

REPEATED ACTION PLOT

REPEATED ACTION PLOT

In this plot, a single character repeats an action over and over with the underlying design mantra of “we are going to keep doing this until we get it right.” This plot could be categorized as a goal-oriented plot, as the protagonist may have a goal, and the obstacles are the repetition of a single action with different outcomes. However, I’ve added it here, because it is a deviation from linear goal-oriented plot.

- Film Examples: Run Lola Run, Groundhog Day, The Butterfly Effect, 50 First Dates.

- Book Examples: Before I Fall (Oliver).

Are these the only plot types that exist? Absolutely not! This is simply the list I’ve created thus far in my search for alternative plots. If you know of more alternative plots, I’d love to hear about them!

For further reading on alternative plots, please take a look at:

- Berg, Charles Ramirez. “A Taxonomy of Alternative Plots in Recent Films: Classifying the ‘Tarantino Effect.’” Film Criticism, Vol. 31, Issue 1-2, 5-57, 22 Sept 2006. Ebsco Host. Web. 6 May 2011.

- Pages 44 -66 in: McKee, Robert. Story: Substance, Structure, Style and the Principles of Screenwriting. New York: IT Books, 1997.

- Pages 165 – 194 in: Gardner, John. The Art of Fiction. New York: Vintage Books, 1983.

Coming up next: Alternative structures!

Thanks for coming back to learn more about alternative plots!

Last week in Part 1, I covered mini-plot, daisy chain plot, cautionary tale plot, and ensemble plot. Today we’re going to continue to push the boundaries of arch plot and the hero’s journey by taking a look at along-for-the-ride plot, symbolic juxtaposition plot, repeated event plot, and repeated action plot. Again, I’ve termed an alternative plot as one that doesn’t have a hero (as defined by the hero’s journey), one that lacks a specific goal, or one that does not use traditional cause-and-effect as its connective tissue.

ALONG FOR THE RIDE PLOT

ALONG FOR THE RIDE PLOT

In the Along for the Ride plot there isn’t an active protagonist. Instead a secondary character drives the action and the protagonist is along for the ride. Often there’s still a change in the protagonist, showing that we don’t always have to be active goal-seekers for an event or person to incite personal growth.

- Book Examples: Looking for Alaska (Green), What I Saw and How I Lied (Blundell), Rebecca (Maurier).

SYMBOLIC JUXTAPOSITION PLOT (Also known as: Thematic Plot, Intellectual Plot, Anti-Plot, Existential Plot)

SYMBOLIC JUXTAPOSITION PLOT (Also known as: Thematic Plot, Intellectual Plot, Anti-Plot, Existential Plot)

In the symbolic juxtaposition plot the reader should be prepared for a more intellectual experience. Instead of traditional cause-and-effect, this plot uses themes, ideas, images, and concepts to connect scenes and sequences with meaning. It’s a more argumentative plot development where X doesn’t cause Y, but X is in a symbolic relationship to Y.

- Film Examples: Life in a Day, The Tree of Life, The Thin Red Line, Chunking Express, Waking Life.

- Book Examples: Einstein’s Dreams (Lightman), Criss Cross (Perkins).

REPEATED EVENT PLOT

REPEATED EVENT PLOT

In classical narrative, the same event is never shown twice. In this plot type, however, one event repeats several times throughout the story, but each re-telling usually offers a new perspective. Multiple characters are used to show that there is more than one version of the truth.

- Film Examples: Vantage Point, Hero, He Loves Me…He Loves Me Not.

REPEATED ACTION PLOT

REPEATED ACTION PLOT

In this plot, a single character repeats an action over and over with the underlying design mantra of “we are going to keep doing this until we get it right.” This plot could be categorized as a goal-oriented plot, as the protagonist may have a goal, and the obstacles are the repetition of a single action with different outcomes. However, I’ve added it here, because it is a deviation from linear goal-oriented plot.

- Film Examples: Run Lola Run, Groundhog Day, The Butterfly Effect, 50 First Dates.

- Book Examples: Before I Fall (Oliver).

Are these the only plot types that exist? Absolutely not! This is simply the list I’ve created thus far in my search for alternative plots. If you know of more alternative plots, I’d love to hear about them!

For further reading on alternative plots, please take a look at:

- Berg, Charles Ramirez. “A Taxonomy of Alternative Plots in Recent Films: Classifying the ‘Tarantino Effect.’” Film Criticism, Vol. 31, Issue 1-2, 5-57, 22 Sept 2006. Ebsco Host. Web. 6 May 2011.

- Pages 44 -66 in: McKee, Robert. Story: Substance, Structure, Style and the Principles of Screenwriting. New York: IT Books, 1997.

- Pages 165 – 194 in: Gardner, John. The Art of Fiction. New York: Vintage Books, 1983.

Coming up next: Alternative structures!

Up to this point in my Organic Architecture Series, I’ve been discussing the goal-oriented plot (arch plot) and the limitations of this plot-type. Arch plot functions in such a way that the connective tissue is a desire that moves the plot through its progression.

But are there plots where the cause-and-effect tissue isn’t defined by goals? Or plots that don’t have heroes? Or plots where the main character isn’t active?

YES!

In the next two posts, I’m going to introduce you to the following alternative plots:

- Mini-plot,

- Daisy chain plot,

- Cautionary tale plot

- Ensemble plot

- Along for the ride plot

- Symbolic juxtaposition plot

- Repeated event plot

- Repeated action plot

This list is by no means complete and I’m constantly on the lookout for more!

I’ve defined an alternative plot as one that doesn’t have a hero (as termed by the hero’s journey), one that lacks a specific goal, or one that does not use traditional cause-and-effect as its connective tissue. Let’s look at how a few of these plots are different than the hero’s journey arch plot.

MINI PLOT (Also known as: Emotional Plot)

MINI PLOT (Also known as: Emotional Plot)

Mini plot is a minimalist approach to arch plot in which the writer reduces the elements of classical design. Often these stories are internal and appear to be plot-less, and/or have passive protagonists. However, the cause-and-effect links are often derived from points of emotional growth rather than high-stakes action. Some might argue that this is a “watered down” version of arch plot, because you can still see the same patterns of arch plot arising in mini-plot, but on a smaller more emotional level.

- Film Examples: Tender Mercies, Five Easy Pieces, Wild Strawberries.

DAISY CHAIN PLOT

DAISY CHAIN PLOT

In the daisy chain plot there is no central protagonist with a goal. Instead multiple characters or situations are introduced through the cause-and-effect connective tissue of a physical object that is passed from one character to the next.

- Film Examples: The Red Violin, Twenty Bucks.

- Book Examples: Lethal Passage (Larson).

- Modified Daisy Chain Plots with a Protagonist: The Strange Case of Origami Yoda (Angleberger), Thirteen Reasons Why (Asher).

CAUTIONARY TALE PLOT

CAUTIONARY TALE PLOT

In the cautionary tale plot there isn’t a hero and it is often the antithesis of comforting growth. In both Chris Lynch’s Inexcusable and Todd Strasser’s Give a Boy a Gun, the main character’s commit horrible acts of violence. In this plot, the reader becomes the protagonist who must evaluate the main character, and it is often the reader who ends up changing as a result.

- Book Examples: Inexcusable (Lynch), Jumped (Williams-Garcia), Give a Boy a Gun (Strasser).

ENSEMBLE PLOT (Also known as: Polyphonic Plot)

ENSEMBLE PLOT (Also known as: Polyphonic Plot)

This plot has multiple protagonists in a single location which is “characterized by the interaction of several voices, consciousnesses, or world views, none of which unifies or is superior to the others” (Berg). There can be goals in this plot type, but more often it is a character-driven story in the form of a portrait of a city, group of friends, or community.

- Film Examples: The Big Chill, Nashville, Beautiful Girls.

- Book Examples: Keesha’s House (Frost), Give a Boy a Gun (Strasser), Bronx Masquerade (Grimes), Doing It (Burgess).

Are you starting to see some of the new and exciting options available? Stay tuned. In part 2, I’ll cover: along for the ride plot, symbolic juxtaposition plot, repeated event plot, and repeated action plot.

Up to this point in my Organic Architecture Series, I’ve been discussing the goal-oriented plot (arch plot) and the limitations of this plot-type. Arch plot functions in such a way that the connective tissue is a desire that moves the plot through its progression.

But are there plots where the cause-and-effect tissue isn’t defined by goals? Or plots that don’t have heroes? Or plots where the main character isn’t active?

YES!

In the next two posts, I’m going to introduce you to the following alternative plots:

- Mini-plot,

- Daisy chain plot,

- Cautionary tale plot

- Ensemble plot

- Along for the ride plot

- Symbolic juxtaposition plot

- Repeated event plot

- Repeated action plot

This list is by no means complete and I’m constantly on the lookout for more!

I’ve defined an alternative plot as one that doesn’t have a hero (as termed by the hero’s journey), one that lacks a specific goal, or one that does not use traditional cause-and-effect as its connective tissue. Let’s look at how a few of these plots are different than the hero’s journey arch plot.

MINI PLOT (Also known as: Emotional Plot)

MINI PLOT (Also known as: Emotional Plot)

Mini plot is a minimalist approach to arch plot in which the writer reduces the elements of classical design. Often these stories are internal and appear to be plot-less, and/or have passive protagonists. However, the cause-and-effect links are often derived from points of emotional growth rather than high-stakes action. Some might argue that this is a “watered down” version of arch plot, because you can still see the same patterns of arch plot arising in mini-plot, but on a smaller more emotional level.

- Film Examples: Tender Mercies, Five Easy Pieces, Wild Strawberries.

DAISY CHAIN PLOT

DAISY CHAIN PLOT

In the daisy chain plot there is no central protagonist with a goal. Instead multiple characters or situations are introduced through the cause-and-effect connective tissue of a physical object that is passed from one character to the next.

- Film Examples: The Red Violin, Twenty Bucks.

- Book Examples: Lethal Passage (Larson).

- Modified Daisy Chain Plots with a Protagonist: The Strange Case of Origami Yoda (Angleberger), Thirteen Reasons Why (Asher).

CAUTIONARY TALE PLOT

CAUTIONARY TALE PLOT

In the cautionary tale plot there isn’t a hero and it is often the antithesis of comforting growth. In both Chris Lynch’s Inexcusable and Todd Strasser’s Give a Boy a Gun, the main character’s commit horrible acts of violence. In this plot, the reader becomes the protagonist who must evaluate the main character, and it is often the reader who ends up changing as a result.

- Book Examples: Inexcusable (Lynch), Jumped (Williams-Garcia), Give a Boy a Gun (Strasser).

ENSEMBLE PLOT (Also known as: Polyphonic Plot)

ENSEMBLE PLOT (Also known as: Polyphonic Plot)

This plot has multiple protagonists in a single location which is “characterized by the interaction of several voices, consciousnesses, or world views, none of which unifies or is superior to the others” (Berg). There can be goals in this plot type, but more often it is a character-driven story in the form of a portrait of a city, group of friends, or community.

- Film Examples: The Big Chill, Nashville, Beautiful Girls.

- Book Examples: Keesha’s House (Frost), Give a Boy a Gun (Strasser), Bronx Masquerade (Grimes), Doing It (Burgess).

Are you starting to see some of the new and exciting options available? Stay tuned. In part 2, I’ll cover: along for the ride plot, symbolic juxtaposition plot, repeated event plot, and repeated action plot.

I want to thank everyone for reading my Organic Architecture Series! I realize this was a long series with lots of posts. The following are the links to all the different articles. Feel free to bookmark this page for easy reference!

I want to thank everyone for reading my Organic Architecture Series! I realize this was a long series with lots of posts. The following are the links to all the different articles. Feel free to bookmark this page for easy reference!

[…] First off, Ingrid Sundberg. Ingrid Sundberg is a fellow VCFA alum. She recently posted a fabulous series taken from her thesis on story architecture. If you only saw bits, or missed the whole thing, bookmark this page which includes the links for the entire series. Organic Architecture: Links to the Whole Series […]

Thank you for this marvelous and informative series! Bookmarking this page for future reference!

Thanks for this wrap-up! You did such an awesome job with this!!!

Thank you for this amazing series, Ingrid! I haven’t thanked you often enough, but yours is the one blog I always read.

You are awesome!

Very impressed by what you’ve managed to put together here.