new posts in all blogs

Viewing: Blog Posts Tagged with: John Truby, Most Recent at Top [Help]

Results 1 - 7 of 7

How to use this Page

You are viewing the most recent posts tagged with the words: John Truby in the JacketFlap blog reader. What is a tag? Think of a tag as a keyword or category label. Tags can both help you find posts on JacketFlap.com as well as provide an easy way for you to "remember" and classify posts for later recall. Try adding a tag yourself by clicking "Add a tag" below a post's header. Scroll down through the list of Recent Posts in the left column and click on a post title that sounds interesting. You can view all posts from a specific blog by clicking the Blog name in the right column, or you can click a 'More Posts from this Blog' link in any individual post.

By:

Cathrin Hagey,

on 3/1/2016

Blog:

The Giant Pie

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

movies,

feminism,

Room,

Huffington Post,

Robert McKee,

heroine's journey,

Emma Donoghue,

John Truby,

My Publications,

Brie Larson,

Jacob Tremblay,

Lenny Abrahamson,

Add a tag

Room (2015) is a movie directed by Lenny Abrahamson, written by Emma Donoghue (based on her award-winning novel), and starring Brie Larson and Jacob Tremblay. It’s about a woman kept prisoner by a rapist in a backyard shed for seven years where she gives birth to a son and raises him for five years before […]

The post The Heroine’s Journey in Room appeared first on Cathrin Hagey.

Too much writing advice is too much. Yet, knowing that doesn’t slow me down from seeking it.

Lately, I’ve been re-examining John Truby’s The Anatomy of Story: 22 Steps To Becoming A Master Storyteller. The guy looks at stories from every possible angle. Among other things, he discusses seven steps of structure that every story needs as it develops over time, in its growth from beginning to end. They are:

-Weakness and need

-Desire

-Opponent

-Plan

-Battle

-Self-revelation

-New equilibrium

These are not something external, such as the three-act structure imposed from the outside. They exist within the story. Truby calls them the nucleus, the DNA of the story. They are based on human action because they are the same steps people must work through to solve problems.

The step I’m currently paused at is an aspect of weakness and need. At the start of a story, the MC must have one or more weaknesses that holds him back from reaching his goal. It should be something so profound, it is ruining his life. This flaw forces a need for the character to overcome the weakness and change or grow in some way. This is a psychological flaw that is hurting no one but the hero. I get that.

Truby says most stories incorporate that. What elevates a so-so story to an excellent one, is a moral flaw. A moral weakness hurts not only the protagonist, but others around him, as well. As an example, he cites the story The Verdict in which the MC, Frank, has a psychological need to overcome his drinking problem and regain his self-respect. His moral flaw is that he uses people for money. In one instance,Frank lies his way into a funeral of strangers, upsetting the family, trying to round up more business.

Okay, I get that, too. And because Truby acknowledges its importance in stories, I give it credence, as well. But how about for an MG character? Do they need to be morally flawed for the story to pop? The stakes are lighter for MG and that’s the nature of it. Experts say there are certain lines not to cross and having the hero be morally corrupt seems like one of them.

But this is John Truby. He really, really knows his stuff. Shouldn’t I listen to him? If Tiger Woods offered tips on your golf swing, seems to me it would be wise not to argue about it. Still, a moral flaw doesn’t feel right for that age level of story.

Looking back over other stories, I can’t think of any MG characters with moral flaws. There must be a few. They have psychological weaknesses to overcome. The strong-willed behavior of Kyra in Carol Lynch Williams’ The Chosen One brings the anger of the prophet down upon her family. That seems like a character strength rather than a flaw and it does raise the stakes for her. Same with Sal in Sharon Creech’s Walk Two Moons. Her denial creates angst with her father, but again, rather than immorality, it seems it’s more a matter of innocence. Both of these works are YA. It could be a YA vs. MG thing. What works for older audiences doesn’t necessarily work for all readers.

Julie Daines posted here a few weeks ago about listening to your gut, your writer’s intuition. That inner voice is telling me to question Truby’s on this. Truby or not Truby, that is the question.

(This article also posted at http://writetimeluck.blogspot.com)

The next project is a rescue. This flat story that has sat in writer purgatory for a few years, waiting for motivation to do something about it, longing for the inspiration to remedy it.

I’m there ready to take it on, its finding the cure that is the problem. Thus, it is back to basics. Characters, stories are about characters. Check. Plot, protagonist wants something, antagonist keeps him from it. Wait, that could be it. I don’t have an antagonist, at least not in the traditional sense.

John Truby (The Anatomy of Story: 22 to Becoming a Master Storyteller) is my go-to guy at a time like this. He says the hero, of course, is important. So, too, is the opponent along with the rest of the cast. Truby focuses not on the main character in isolation, but looks at all the characters as part of an interconnected web. Writer’s Digest this week had a quote by mystery writer Elmore Leonard who says “the main thing I set out to do is tell the point of view of the antagonist as much as the good guy.”

This is all well and fine, but what if your my story doesn’t have a

Hmm. Good points, but I still don’t have a traditional antagonist. There is no detective and no criminal to pursue, my Harry Potter has no Voldemort. My protagonist has only his own shortcomings to trip over. Truby doesn’t directly address such a thing. He does illustrate his points with story examples from movies. The likes of A Streetcar Named Desire, The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn, andTootsie, don’t have traditional antagonists.

Another valuable resource, KM Weiland, discusses an “antagonistic force” and says, “nowhere is it written that your story has to have a bad guy (or girl, as the case may be).” She says there are several non-human antagonists. They include: -Animal - King Kong and Jaws comes to mind

-Self - the age old existential quandary of man as his own worst enemy in which the MC must overcome his own problems before he can deal with the external one

-Setting - survival stories in which the hero goes up against nature. Cast Away is a good example. Weather related tales are an offshoot of this.

-Society - dystopia is the extreme example here, but simpler themes in which the protagonist faces poverty or inequalities of some sort

-Supernatural forces - The Curious Case of Benjamin Button would be of this sort.

-Technology - a lot of sci-fi uses overarching technological forces as antagonists.

Non-human antagonists can be anything that throws obstacles in the way or the hero getting what he or she wants. They could be a thing, an idea, or any inanimate object that the protagonist must overcome to reach the end goal of the story. As long as you have conflict (to have a story is a must) you have an antagonist.

Weiland says one mustn’t limit themselves to just one antagonist and most stories will use a combination of several.

Think Sharnado.

(This article also posted at http://writetimeluck.blogspot.com)

The “next” project is one I’ve been working on forever.

Okay, not forever, but for 30 years or more. It was an MG story conceived, then started, then abandoned (but not forgotten). It was the one that got me into writing. I spent a few years on it and as I sent it out, editors and agents pointed out some glaring issues with it. By then, not only was I into a new project, but had become weary of it and had no more energy to devote to it.

This year I brought it out again, blew off the dust, repackaged it as a YA, and workshopped it at WIFYR. There I was struck by an inner voice, perhaps the ten-year old stuck in my head, that said I’m an MG writer, not a YA. Okay, back to working it for younger readers.

Still, the story is missing something, no matter what audience it reaches.

Imitation of those who do it well seemed like a good strategy, so I’ve been re-reading exemplary MG stories.

In A Clockwork Three, Matthew J. Kirby gives his three main characters something to work for then expertly raises the stakes making it harder for them to achieve it. Sharon Creech’s Walk Two Moons is a richly woven tale about Salamanca, a girl searching for answers to the disappearance of her mother. A supporting cast of characters are among the reason this book resonates. Solveig in Kirby’s Icefall also involves a compelling protagonist who rides on the shoulders of strong supporting characters. The lesson here: stories are about people.

I also revisited John Truby’s The Anatomy of Story. He says writers need to focus not just on the hero, but the whole web of characters that help define him. Most writers start by listing traits of the MC, write a tale about him, then force a change in the end. Truby says this is wrong, that the hero does not act alone in a vacuum. The most important step in developing your MC is to connect and compare them to others. This forces you to distinguish the hero in unique ways. As in life, we are affected not just by our families and co-workers, but by the idiot that cut you off in traffic, the writer that brought you to tears with her prose, or the politician whose ideology you disagree with. How we react defines our character. The heroes in our stories are no less so connected to the web of characters in our stories.

Truby provides a writing exercise to help build your character web. It is worth looking into.

Okay, “next” project. I’ve got my eye on you. I don’t know if you’re going YA or MG, but you are going to have some interesting people carrying you along.

(This article also posted at http://writetimeluck.blogspot.com)

I’m my previous posts I’ve given you a pandora’s box of alternative plots (Alt. Plots Part 1 and Alt. Plots Part 2) as well as alternative structures (Alt. Structures Part 1 and Alt. Structures Part 2). And we ought to take classic design, the hero’s journey, and three act structure and throw them in that box as well.

But how do we use these?

How do we incorporate them into our writing process in a way that is organic? How do we make sure they come naturally from the story itself without becoming a dead-in-the-water template?

John Truby suggests that the best way to do this not through an external structure, but to look inside the work for an inherent designing principal. Truby is a little abstract in his definition of a designing principal, so here’s my cobbled-together version from what he says in the Anatomy of Story:

Does that sound like a bunch of writerly-MFA-mumbo jumbo? Let me give you some examples to help us understand the concept.

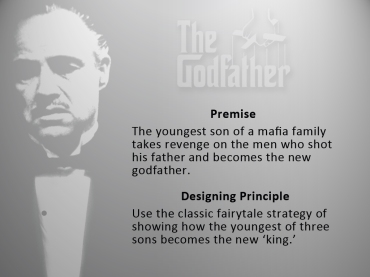

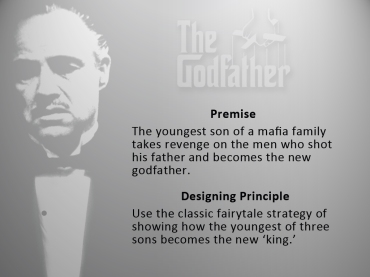

In the film The Godfather, the premise is: The youngest son of a Mafia family takes revenge on the men who shot his father and becomes the new Godfather. The idea of a designing principal is to find something that derives from that premise and those characters which adds a new layer of meaning, giving the story its originality, and acts as a guide for the writing process.

According to Truby, the designing principal of The Godfather is: “Use the classic fairy tale strategy of showing how the youngest of three sons becomes the new ‘king.’” With this underlying design the story is no longer generically about the mafia or revenge. Through the use of a fairy tale trope the story becomes elevated to one of legend. The fairy tale offers the writer a basic scaffolding for plot structure and there’s opportunity for thematic comparisons between the original story and its re-telling.

According to Truby, the designing principal of The Godfather is: “Use the classic fairy tale strategy of showing how the youngest of three sons becomes the new ‘king.’” With this underlying design the story is no longer generically about the mafia or revenge. Through the use of a fairy tale trope the story becomes elevated to one of legend. The fairy tale offers the writer a basic scaffolding for plot structure and there’s opportunity for thematic comparisons between the original story and its re-telling.

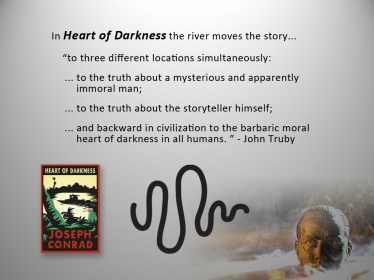

Another example is the use of a traveling metaphor such as a river. In Heart of Darkness, the protagonist, Marlow, is taking a boat ride up the river and progressing deeper and deeper into the jungle. The river is a designing principle for both structure and metaphor, moving the story into “three different locations simultaneously: to the truth about a mysterious and apparently immoral man” who Marlow is going up the river to find, providing plot structure for the external story. “To the truth about the storyteller himself;” a metaphor for the internal emotional story as the protagonist goes deeper into his own psyche. And it moves us “backward in civilization to the barbaric moral heart of darkness in all humans,” the novel’s underlying theme. The traveling metaphor contains the external story, the internal story, and the theme. No wonder this book is a classic.

There is no one way to create a designing principal, there are hundreds of them, and the one that is right for your story only you can find. But I’ve noticed certain “categories” if you will, certain patterns that designing principals sometimes fall under. The execution of each is unique to the themes and characters of each book, but I want to present the list I’ve generated thus far, as a jumping off point. My goal is to further illustrate this concept and to help you think about what might be the designing principal of your book.

There is no one way to create a designing principal, there are hundreds of them, and the one that is right for your story only you can find. But I’ve noticed certain “categories” if you will, certain patterns that designing principals sometimes fall under. The execution of each is unique to the themes and characters of each book, but I want to present the list I’ve generated thus far, as a jumping off point. My goal is to further illustrate this concept and to help you think about what might be the designing principal of your book.

I have six categories that I will discuss in my next posts:

1. A Character’s Mental State

2. Setting and Environment

3. Time

3. Community

4. Fairy Tales, Myth and Parallel Stories

6. Storyteller

Read more about John Truby’s concept of a designing principal on pages 25-29 of The Anatomy of Story.

By: Bruce Luck,

on 2/16/2013

Blog:

Utah Children's Writers

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

SCBWI,

Kathleen Duey,

Cheryl Klein,

Ann Dee Ellis,

Martine Leavitt,

John Truby,

The Anatomy of Story,

WiFYR,

Alane Ferguson,

Mathew Kirby,

Add a tag

I think I’m studying this thing too much. When I first began writing, I wrote carefree, jotting down events as they came to mind. Then I was introduced to WIFYR and became aware that there are formats and procedures and formulae to follow. More and more, I began to research what the experts were saying on writing. Now I’ve got so many “do this, don’t do that” things going on in my head, I’m bound to go against some expert’s opinion with every sentence I write.

Cheryl Klein, Martine Leavitt, Alane Ferguson, Ann Dee Ellis, Mathew Kirby, Kathleen Duey; these are some of the gurus to whose savvy advice I try to adhere. The latest is John Truby. I recently caught up on some back copies of the SCBWI journal when I ran across an article in the November/December issue. It talked about Truby’s book, The Anatomy of Story: 22 Steps to Becoming a Master Storyteller. Silly me. I went out and purchased it.

I’m not sure which of the 22 steps I’m on, as they are not readily laid out in the table of contents. Truby addresses story anatomy from a screenwriter’s perspective but his concepts can be adapted to any fiction writing. I’m on the chapter about story structure. Truby says story structure is how a story develops over time.

He says your MC must have a weakness and a need. The weakness could be the character is arrogant or selfish or a liar and the need is to overcome the weakness. Then there must be desire, which is not the same as need. Desire is what the character wants. It is the driving force in the story and something the reader hopes he attains. Need has to do with a weakness within the character and desire is a goal outside of the character. The hero must, of course meet an opponent. Truby says the opponent does not try to prevent the MC from accomplishing their goal as much as they are in competition for the same thing. In a mystery story, it would seem the protagonist is opposed to the perpetrator of the crime. Under the surface, however, they are both competing for their version of the truth to be believed.

This is where the conflict is with my work-in-progress (my incredibly slow work-in-progress). It’s a middle grade book, so the story is not as intricate. Do kid characters need the complexity of adult characters? I get it that you can’t make them too sterile, too one-sided. Should a middle grade MC be arrogant or a liar?

Likewise, I’m having trouble with the opponent aspect. In my story, there is no real antagonist. There is a mystery the MC is trying to solve, but no person is preventing him.

The experts say do this or do that. My gut tells me different. What’s a poor writer to do?

.jpg?picon=980)

By:

Cheryl Rainfield,

on 4/13/2011

Blog:

Cheryl Rainfield: Avid Reader, Teen Fiction Writer, and Book-a-holic. Focus on Children & Teen Books

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

writing process,

writing method,

writing technique,

john truby,

linda seeger,

michael hauge,

toronto screenwriters conference,

writing tips,

writing advice,

Uncategorized,

Add a tag

I’ve thought for several years now that screenwriting books teach story structure and plot more clearly, practically, and fully than many books for novelists, with more insight and in a way that works (though I’ve also learned a ton from fiction writing techniques–but not so much on structure). So I’m glad I went to the Toronto Screenwriters’ Summit this past weekend with some fellow children’s and YA writers.

I got a lot out of the weekend-long conference. Perhaps because I’ve worked on writing technique for years, and because I think I already have a strong voice in my writing, I found John Truby and Michal Hauge’s speeches that delved into more advanced plot and structure techniques the most helpful.

Linda Seeger emphasized the importance of finding one’s own voice, and of learning as much as you can about your own creative process and doing what works for you–both of which I really agree with. Something I hadn’t thought about in a long time that made me rewrite a part of the manuscript I’m working on now was her talking about choosing the right season for your work–that seasons can be metaphorical. She also recommended several books–her own, of course, since she’s a successful script consultant, including Making a Good Script Great–as well as Experiences In Visual Thinking by Robert McKim and Put Your Mother On the Ceiling by Richard de Mille to learn to think, and thus write, more visually.

I like that she talked about the need to have some unconscious time with your work, or incubation, which I tend to do naturally.

John Truby talked in depth and in great detail about how to structure a story so that it works on a deep level. I highly recommend his book The Anatomy of Story to really understand and successfully structure a book. It makes the whole process easy to understand. He talks about 7 basic steps, and then 22 steps–and all of them made sense to me, including the hero’s weakness and need (weakness: one or more serious flaws that hurt the hero’s life, and needs which are based on that weakness), desire (the hero’s goal–what she wants in the story), the opponent or antagonist (who tries to prevent the hero from reaching her goal and who wants the same goal as the hero but for different reasons), and the self-revelation. (Check out his book for all the steps and much greater detail.)

John also talked about figuring out which genre your story fits in (or which meld of genres), which will change or add to the seven steps. I think here is where novels may differ. I found myself thinking that my novels are drama, with some suspense and some love thrown in–but drama was not one of the genres.

John offered such a wealth of information that I almost couldn’t write fast enough! Though it was like a review for me, since I’ve read his book, it was a great reminder, and I found myself absorbing the information.

Michael Hauge also talked about structure, with some similarities to John Truby, and some differences and different emphasis, so both talks built on and complimented each other. I also couldn’t write fast enough with him! I really liked how Michael said that the one thing we must know to be a good storytelling is how to elicit emotion through our writing. I know that when I’m emotionally involved with a character, I care more about them and I keep reading. Michael said that story structure is built on three basic elements–character, desire, and conflict–as well as an outer, visible journey for the hero, and an inner, invisible journey. I think the inner journey helps bring meaning to a story. Michael also said that conflict is what keeps us interested (and conflict is not or does not have to be physical).

I’m looking forward to your future posts about the six categories. Thanks!

Wow. I saw The Godfather and never thought about the fairy tale aspect. Very intriguing! Makes the story so much richer.