new posts in all blogs

Viewing: Blog Posts Tagged with: Energic Plot, Most Recent at Top [Help]

Results 1 - 4 of 4

How to use this Page

You are viewing the most recent posts tagged with the words: Energic Plot in the JacketFlap blog reader. What is a tag? Think of a tag as a keyword or category label. Tags can both help you find posts on JacketFlap.com as well as provide an easy way for you to "remember" and classify posts for later recall. Try adding a tag yourself by clicking "Add a tag" below a post's header. Scroll down through the list of Recent Posts in the left column and click on a post title that sounds interesting. You can view all posts from a specific blog by clicking the Blog name in the right column, or you can click a 'More Posts from this Blog' link in any individual post.

By: Ingrid Sundberg,

on 6/12/2013

Blog:

Ingrid's Notes

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

Plot,

Writing Craft,

Story Structure,

The Hero's Journey,

The Universal Story,

Energic Plot,

Classic Plot,

Classic Design,

Goal Oriented Plot,

Mythic Structure,

Add a tag

From my previous posts outlining the major beats of classic design (aka: arch plot, the universal story, mythic structure, the hero’s journey, etc.) you’ve seen that this design is very precise. If done well this “universal story” creates a satisfying story experience where all the pieces seem to fall effortlessly into place. It’s clean. It’s inspiring. It’s tempting to use such a beautiful template to organize our stories as well. And at first glance – why shouldn’t we? After all classic design is touted as:

From my previous posts outlining the major beats of classic design (aka: arch plot, the universal story, mythic structure, the hero’s journey, etc.) you’ve seen that this design is very precise. If done well this “universal story” creates a satisfying story experience where all the pieces seem to fall effortlessly into place. It’s clean. It’s inspiring. It’s tempting to use such a beautiful template to organize our stories as well. And at first glance – why shouldn’t we? After all classic design is touted as:

“… the story of life. Since before time was recorded, it has been transforming simple words into masterpieces … [it] is the undercurrent of every breath you take, every story you tell yourself, and all the stories you write.” –Martha Alderson (The Plot Whisperer)

“Aristotle’s story structure works, and in fact it is the only structure that has ever worked, because it is a mirror of our own views on the universe.” — Lisa Doan (Plot Structure)

In his book Story, Robert McKee has the grace to acknowledge other plots, but goes on to point out that a writer must earn a living at writing, and according to him you can’t do that without arch plot because “classical design is a mirror of the human mind.”

In his book Story, Robert McKee has the grace to acknowledge other plots, but goes on to point out that a writer must earn a living at writing, and according to him you can’t do that without arch plot because “classical design is a mirror of the human mind.”

With these kinds of endorsements why would you ever consider an alternate story structure?

Vermont College of Fine Arts faculty member Shelley Tanaka posed the following question in one of her lectures:

“Is there such a thing as a universal child?”

I’m sure you know the answer to that question. So how can there possibly be such a thing as a universal story? How can there only be one story of life, one view of the universe, or one mirror of the human mind? Katie Bayerl notes in her graduate thesis that “a single narrative structure, no matter how flexible, can’t possibly address the diverse needs of readers.”

And yet we are constantly encouraged to use this one form of design.

In Anatomy of Story, John Truby points out that “one of the great principals of storytelling is that structure doesn’t just carry content; it is content.” And McKee says that: “Our appetite for story is a reflection of [our] … need to grasp the patterns of living … Fiction [is] a vehicle that carries us on our search for reality … story is a metaphor for life … [it] gives life its form.” So, if we seek story as a guide for how to live our lives, and if structure is the content that reveals that guide, then we ought to consider what this one universal story has to say.

Katie Bayerl notes that the hero’s journey plot is “comforting in its familiarity and in its emphasis on an individual’s ability to triumph over adversity … it is the dominant American narrative of progress and individualism. For writer’s who don’t question those belief systems the hero’s journey may feel like the best way to tell a good story. For those with an agenda of empowerment, it may appear like the only option.”

And for Joeseph Campbell (the founder of mythic structure), it turns out he may have had an agenda of empowerment. Bayerl notes that he “became obsessed with the hero’s journey because he was troubled by what he perceived as the despair of his times; he believed that elevating heroic myths would heal the collective psyche. Campbell explains how the hero myth can support healthy psychological growth when people recognize their own problems in the ordeals of the mythic … and are reassured by the stories that give them abundant, time-tested strategies for survival, success, and happiness.” This is exactly what Truby and McKee meant when they said structure can be used as a metaphor for how to live our lives.

And for Joeseph Campbell (the founder of mythic structure), it turns out he may have had an agenda of empowerment. Bayerl notes that he “became obsessed with the hero’s journey because he was troubled by what he perceived as the despair of his times; he believed that elevating heroic myths would heal the collective psyche. Campbell explains how the hero myth can support healthy psychological growth when people recognize their own problems in the ordeals of the mythic … and are reassured by the stories that give them abundant, time-tested strategies for survival, success, and happiness.” This is exactly what Truby and McKee meant when they said structure can be used as a metaphor for how to live our lives.

But what are the psychological implications of this structure?

1) Are Our Lives Defined by Lack of Desire?

By creating a story design that is driven by goals and desires, are we saying this is the only way in which to define our worth and success? Bayerl asks: “Does it mean our lives must always be defined by lack of desire? Are we failures if we cannot independently solve every problem that faces us? Must we all be heroes?”

2) Does it Create a False Sense of Values?

2) Does it Create a False Sense of Values?

When a plot is goal-oriented and revolves around achieving a task (getting the girl, saving the world, winning the race, etc.) does it create a false sense of values? Instead of searching for wisdom, do we put value in the search for an external goal only to find ourselves disappointed?

3) Does it Limit Our Vision to Only One Aspect of Existence?

Diane Lefer quotes Ursula Le Guin in questioning if this structure isn’t a rather “gladiatorial view of fiction” one where we’re “… taught to focus our stories on a central struggle, [and] … by default base all our plots on the clash of opposing forces. We limit our vision to a single aspect of existence and overlook much of the richness and complexity of our lives, just the stuff that makes a work of fiction memorable.”

4) Is it Socially Coercive?

Young adult author Amy Rose Capetta’s lecture on catharsis discusses how a pleasurable catharsis can be the result of Aristotelian structure, but she goes on to introduce Augusto Boal’s opinions on the matter, wherein he suggests that this type of catharsis is socially coercive. Capetta explains that “Boal was convinced that catharsis as it was presented by Aristotle, was not just normative in that it returned the audience to their default emotional state, but that in fact it served a socially normative function, reinforcing and upholding the status quo.”

5) Does it Perpetuate an Untrue American Myth?

5) Does it Perpetuate an Untrue American Myth?

And lastly, Malcolm Gladwell’s non-fiction book Outliers, has pretty much de-bunked the modern American myth that if you set yourself out a goal, and you try hard enough to overcome the obstacles, you’ll succeed. This simply isn’t true. So why do we continually write stories about hero’s overcoming obstacles and succeeding in the end as if it is the natural order of things?

Is it possible that the hero’s journey myth, is just that – a myth. After all, it does initially derive from stories of mythology, and not actual experiences. Not to mention that the popularization of this design is relatively new. Yes, it shows up in ancient works and the classics of western literature. But it’s elevation as the end-all be-all of storytelling started in the 1950’s with Campbell’s research and was greatly escalated by the influence Star Wars on American film. Is it possible that arch plot and mythic structure are the predominant storytelling paradigm of our time and not a universal story?

Am I saying that we shouldn’t use this storytelling plot and structure?

No.

But I think you should ask yourself why you’re using it, and not use it blindly because there’s an implication that it’s the only type of design that exists.

Don’t fret! The coming posts will introduce you to the wide variety of plots and structures that will take you beyond arch plot and mythic structure. Stay tuned and see how many options really are available to you!

WORKS CITED:

Alderson, Martha. The Plot Whisperer: Secrets of Story Structure Any Writer Can Master. New York: Adams Media, 2011.

Bayerl, Katie. “Must We All Be Heroes? Crafting Alternatives to the Hero’s Journey in YA Fiction.” Critical Thesis. Vermont College of Fine Arts, 2009.

Bayerl, Katie. “Must We All Be Heroes? Crafting Alternatives to the Hero’s Journey in YA Fiction.” Graduate Lecture. Vermont College of Fine Arts, Montepelier, VT. July 2009.

Capetta, Amy Rose. “Can’t Fight This Feeling: Figuring out Catharsis and the Right One for Your Story.” Graduate Lecture. Vermont College of Fine Arts, Montepelier, VT. Jan 2012.

Doan, Lisa. “Plot Structure: The Same Old Story Since Time Began?” Critical Essay. Vermont College of Fine Arts, 2006.

Lefer, Diane. “Breaking the Rules of Story Structure.” Words Overflown by Stars. Ed. David Jauss, Cincinnati: Writer’s Digest Books, 2009. 62-69.

McKee, Robert. Story: Substance, Structure, Style and the Principles of Screenwriting. New York: IT Books, 1997.

Tanaka, Shelley. “Books from Away: Considering Children’s Writers from Around the World.” Faculty Lecture. Vermont College of Fine Arts, Montpelier, VT. Jan 2010.

Truby, John. The Anatomy of Story: 22 Steps to Becoming a Master Storyteller. New York: Faber and Faber Inc., 2007.

By: Ingrid Sundberg,

on 6/12/2013

Blog:

Ingrid's Notes

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

Plot,

Writing Craft,

Story Structure,

The Hero's Journey,

The Universal Story,

Energic Plot,

Classic Plot,

Classic Design,

Goal Oriented Plot,

Mythic Structure,

Add a tag

From my previous posts outlining the major beats of classic design (aka: arch plot, the universal story, mythic structure, the hero’s journey, etc.) you’ve seen that this design is very precise. If done well this “universal story” creates a satisfying story experience where all the pieces seem to fall effortlessly into place. It’s clean. It’s inspiring. It’s tempting to use such a beautiful template to organize our stories as well. And at first glance – why shouldn’t we? After all classic design is touted as:

From my previous posts outlining the major beats of classic design (aka: arch plot, the universal story, mythic structure, the hero’s journey, etc.) you’ve seen that this design is very precise. If done well this “universal story” creates a satisfying story experience where all the pieces seem to fall effortlessly into place. It’s clean. It’s inspiring. It’s tempting to use such a beautiful template to organize our stories as well. And at first glance – why shouldn’t we? After all classic design is touted as:

“… the story of life. Since before time was recorded, it has been transforming simple words into masterpieces … [it] is the undercurrent of every breath you take, every story you tell yourself, and all the stories you write.” –Martha Alderson (The Plot Whisperer)

“Aristotle’s story structure works, and in fact it is the only structure that has ever worked, because it is a mirror of our own views on the universe.” — Lisa Doan (Plot Structure)

In his book Story, Robert McKee has the grace to acknowledge other plots, but goes on to point out that a writer must earn a living at writing, and according to him you can’t do that without arch plot because “classical design is a mirror of the human mind.”

In his book Story, Robert McKee has the grace to acknowledge other plots, but goes on to point out that a writer must earn a living at writing, and according to him you can’t do that without arch plot because “classical design is a mirror of the human mind.”

With these kinds of endorsements why would you ever consider an alternate story structure?

Vermont College of Fine Arts faculty member Shelley Tanaka posed the following question in one of her lectures:

“Is there such a thing as a universal child?”

I’m sure you know the answer to that question. So how can there possibly be such a thing as a universal story? How can there only be one story of life, one view of the universe, or one mirror of the human mind? Katie Bayerl notes in her graduate thesis that “a single narrative structure, no matter how flexible, can’t possibly address the diverse needs of readers.”

And yet we are constantly encouraged to use this one form of design.

In Anatomy of Story, John Truby points out that “one of the great principals of storytelling is that structure doesn’t just carry content; it is content.” And McKee says that: “Our appetite for story is a reflection of [our] … need to grasp the patterns of living … Fiction [is] a vehicle that carries us on our search for reality … story is a metaphor for life … [it] gives life its form.” So, if we seek story as a guide for how to live our lives, and if structure is the content that reveals that guide, then we ought to consider what this one universal story has to say.

Katie Bayerl notes that the hero’s journey plot is “comforting in its familiarity and in its emphasis on an individual’s ability to triumph over adversity … it is the dominant American narrative of progress and individualism. For writer’s who don’t question those belief systems the hero’s journey may feel like the best way to tell a good story. For those with an agenda of empowerment, it may appear like the only option.”

And for Joeseph Campbell (the founder of mythic structure), it turns out he may have had an agenda of empowerment. Bayerl notes that he “became obsessed with the hero’s journey because he was troubled by what he perceived as the despair of his times; he believed that elevating heroic myths would heal the collective psyche. Campbell explains how the hero myth can support healthy psychological growth when people recognize their own problems in the ordeals of the mythic … and are reassured by the stories that give them abundant, time-tested strategies for survival, success, and happiness.” This is exactly what Truby and McKee meant when they said structure can be used as a metaphor for how to live our lives.

And for Joeseph Campbell (the founder of mythic structure), it turns out he may have had an agenda of empowerment. Bayerl notes that he “became obsessed with the hero’s journey because he was troubled by what he perceived as the despair of his times; he believed that elevating heroic myths would heal the collective psyche. Campbell explains how the hero myth can support healthy psychological growth when people recognize their own problems in the ordeals of the mythic … and are reassured by the stories that give them abundant, time-tested strategies for survival, success, and happiness.” This is exactly what Truby and McKee meant when they said structure can be used as a metaphor for how to live our lives.

But what are the psychological implications of this structure?

1) Are Our Lives Defined by Lack of Desire?

By creating a story design that is driven by goals and desires, are we saying this is the only way in which to define our worth and success? Bayerl asks: “Does it mean our lives must always be defined by lack of desire? Are we failures if we cannot independently solve every problem that faces us? Must we all be heroes?”

2) Does it Create a False Sense of Values?

2) Does it Create a False Sense of Values?

When a plot is goal-oriented and revolves around achieving a task (getting the girl, saving the world, winning the race, etc.) does it create a false sense of values? Instead of searching for wisdom, do we put value in the search for an external goal only to find ourselves disappointed?

3) Does it Limit Our Vision to Only One Aspect of Existence?

Diane Lefer quotes Ursula Le Guin in questioning if this structure isn’t a rather “gladiatorial view of fiction” one where we’re “… taught to focus our stories on a central struggle, [and] … by default base all our plots on the clash of opposing forces. We limit our vision to a single aspect of existence and overlook much of the richness and complexity of our lives, just the stuff that makes a work of fiction memorable.”

4) Is it Socially Coercive?

Young adult author Amy Rose Capetta’s lecture on catharsis discusses how a pleasurable catharsis can be the result of Aristotelian structure, but she goes on to introduce Augusto Boal’s opinions on the matter, wherein he suggests that this type of catharsis is socially coercive. Capetta explains that “Boal was convinced that catharsis as it was presented by Aristotle, was not just normative in that it returned the audience to their default emotional state, but that in fact it served a socially normative function, reinforcing and upholding the status quo.”

5) Does it Perpetuate an Untrue American Myth?

5) Does it Perpetuate an Untrue American Myth?

And lastly, Malcolm Gladwell’s non-fiction book Outliers, has pretty much de-bunked the modern American myth that if you set yourself out a goal, and you try hard enough to overcome the obstacles, you’ll succeed. This simply isn’t true. So why do we continually write stories about hero’s overcoming obstacles and succeeding in the end as if it is the natural order of things?

Is it possible that the hero’s journey myth, is just that – a myth. After all, it does initially derive from stories of mythology, and not actual experiences. Not to mention that the popularization of this design is relatively new. Yes, it shows up in ancient works and the classics of western literature. But it’s elevation as the end-all be-all of storytelling started in the 1950’s with Campbell’s research and was greatly escalated by the influence Star Wars on American film. Is it possible that arch plot and mythic structure are the predominant storytelling paradigm of our time and not a universal story?

Am I saying that we shouldn’t use this storytelling plot and structure?

No.

But I think you should ask yourself why you’re using it, and not use it blindly because there’s an implication that it’s the only type of design that exists.

Don’t fret! The coming posts will introduce you to the wide variety of plots and structures that will take you beyond arch plot and mythic structure. Stay tuned and see how many options really are available to you!

WORKS CITED:

Alderson, Martha. The Plot Whisperer: Secrets of Story Structure Any Writer Can Master. New York: Adams Media, 2011.

Bayerl, Katie. “Must We All Be Heroes? Crafting Alternatives to the Hero’s Journey in YA Fiction.” Critical Thesis. Vermont College of Fine Arts, 2009.

Bayerl, Katie. “Must We All Be Heroes? Crafting Alternatives to the Hero’s Journey in YA Fiction.” Graduate Lecture. Vermont College of Fine Arts, Montepelier, VT. July 2009.

Capetta, Amy Rose. “Can’t Fight This Feeling: Figuring out Catharsis and the Right One for Your Story.” Graduate Lecture. Vermont College of Fine Arts, Montepelier, VT. Jan 2012.

Doan, Lisa. “Plot Structure: The Same Old Story Since Time Began?” Critical Essay. Vermont College of Fine Arts, 2006.

Lefer, Diane. “Breaking the Rules of Story Structure.” Words Overflown by Stars. Ed. David Jauss, Cincinnati: Writer’s Digest Books, 2009. 62-69.

McKee, Robert. Story: Substance, Structure, Style and the Principles of Screenwriting. New York: IT Books, 1997.

Tanaka, Shelley. “Books from Away: Considering Children’s Writers from Around the World.” Faculty Lecture. Vermont College of Fine Arts, Montpelier, VT. Jan 2010.

Truby, John. The Anatomy of Story: 22 Steps to Becoming a Master Storyteller. New York: Faber and Faber Inc., 2007.

By: Ingrid Sundberg,

on 6/10/2013

Blog:

Ingrid's Notes

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

Classic Design,

Classic Plot Design,

Plot,

Writing Craft,

Structure,

Story Structure,

Plot Structure,

The Hero's Journey,

Energic Plot,

Add a tag

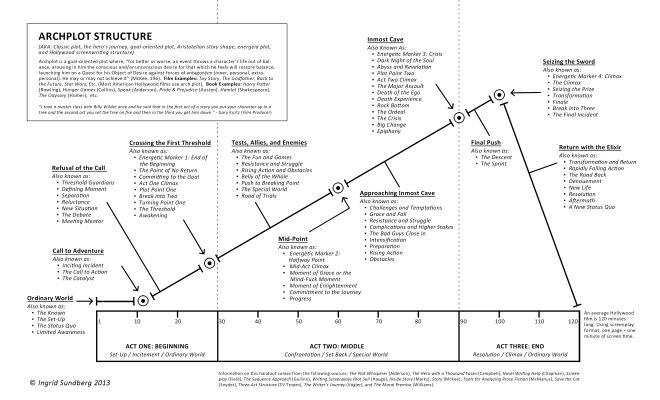

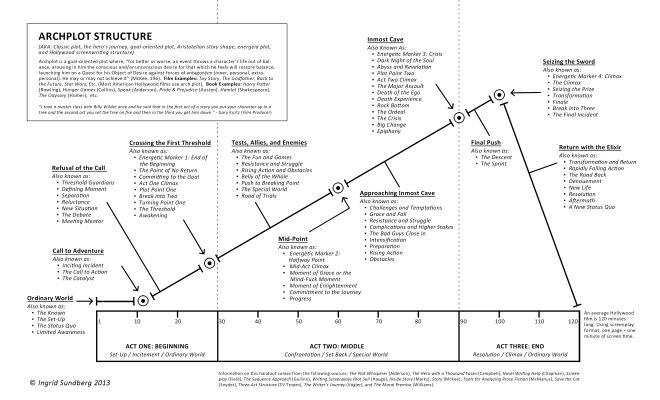

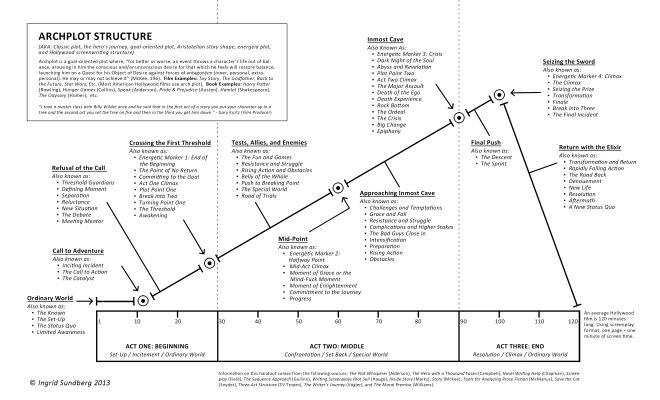

Last week I started off my Organic Architecture series by outlining the eleven major story-beats of classical design. Before I jump into alternative structures and plots I want to make sure we understand arch plot as more than just a template for story. I want to show how this story-frame can be used, and used well.

Today I’m going to breakdown the major beats of classical design using Pixar’s film Toy Story. This film is an excellent example of how arch plot can create a satisfying story experience that moves like a well-oiled machine and every piece has a purpose. Let’s take a look at how the eleven steps outlined in my previous post are put into practice.

ACT ONE:

1) Ordinary World

In the first images of Toy Story we’re introduced to Andy and his favorite toy Sheriff Woody (our protagonist). In the first minutes we establish Woody’s ordinary world, consisting of Andy’s room. At minute four, we get the story hook: the toys come to life. At this point we’re introduced to the major players: Mr. Potato Head, Slinky-dog, Bo-Peep, etc. Relationships are hinted at and we see that Woody is the leader of this clan. The complexity of this world deepens when the first obstacle is introduced, allowing us to see how Woody normally functions in the ordinary world. The obstacle is Andy’s birthday party and a covert toy-style mission to see if there are any new, bigger and brighter, toys to be worried about. This action reveals the emotional core of the film: every toy’s deepest fear is that they will be replaced and Andy will no longer love them. In the first twelve minutes the film has set up the world, how it works, and what’s at stake.

2) The Call to Action

At minute fourteen, Buzz Lightyear shows up on screen. Something new has arrived to disrupt the ordinary world. This is what the hero’s journey calls the call to adventure. In Toy Story the call isn’t an invitation to a quest, but it is a catalyst that disrupts Woody’s status quo. Woody tells himself that this new toy isn’t going to change anything and we enter…

3) The Refusal of the Call

This is the debate section where Woody tries to keep his authority, but is slowly usurped by Buzz.

4) Crossing the First Threshold

Woody’s refusal culminates when his flaws of pride and jealousy cause him to pick a fight with Buzz. Both toys fall out of the car and Andy’s family drives away, leaving Woody and Buzz on the pavement. The two have now become LOST TOYS! This is the moment when Woody and Buzz cross the first threshold and move us into act two. This is the point of no return. Woody and Buzz are no longer in the ordinary world but the special world, which will force them to grow. The energy of the story changes here because the two have a new desire: to get home.

ACT TWO:

5) Tests, Allies, and Enemies

The next seventeen minutes of the film constitutes the fun and games section where our heroes are presented with tests, allies, and enemies. When I went to film school we called this the “trailer section.” It’s where all the gags and jokes used in a film trailer come from. This is the section of the story that fulfills the promise of your premise. Toy Story’s premise is: how do two rival toys find their way home when lost in the real world? Well, they hitch a ride to pizza planet. They get chosen by The Claw and taken home by the evil neighbor Sid. They defend themselves against cannibal toys. Each obstacle gets harder and harder. And it leads us to…

6) The Mid-Point

In the hero’s journey there isn’t actually a mid-point, but in screenwriting it has become very important story beat. It’s where the energy of the film swings up, or swings down. In Toy Story it swings down. Buzz comes upon a TV commercial selling Buzz Lightyear action figures and realizes he is not the Buzz Lightyear, but actually a TOY!

7) Approaching the In-Most Cave

The mid-point also affects Woody and propels the story into the next section. Woody continues to put out fires while Buzz has his existential crisis. This is known as approaching the in-most cave or continued obstacles and intensification.

8) The In-Most Cave

At minute 57, Woody hits rock bottom and reaches the in-most cave or crisis of the story. Both Woody and Buzz are trapped, Woody’s friends have abandoned him, and he can now see that his pride has led him astray.

ACT THREE:

9) The Final Push

Just after the crisis usually comes a change in fate. Sid takes Buzz into the backyard to blow him up and Woody realizes he must save the only friend he has left. This propels us into act three and the final push where Woody devises a rescue plan.

10) Seizes the Sword

Woody enacts his plan in the climax and seizes the sword by saving Buzz’s life!

11) The Return Home

But the return home is still wrought with tension as Woody and Buzz chase down the moving van. Some consider this a second final climax (think horror films where monsters you thought were dead jump out at the last minute). Woody grows by putting his pride aside and works together with Buzz to reunite with Andy. As the film closes Buzz and Woody have returned to the new ordinary world with the wisdom and friendship of their adventure.

This is classic design used well! It creates an emotionally engaging and well-paced story. If you like this story design I highly suggest reading Sheryl Scarborough’s guest post that continues this discussion in regards to three-act structure.

However, despite popular belief, classic design is not the only way to tell a story. My next post will outline the hidden agenda of arch plot and why we need more storytelling options!

By: Ingrid Sundberg,

on 6/10/2013

Blog:

Ingrid's Notes

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

The Hero's Journey,

Energic Plot,

Plot,

Structure,

Story Structure,

Plot Structure,

Classic Design,

Classic Plot Design,

Writing Craft,

Add a tag

Last week I started off my Organic Architecture series by outlining the eleven major story-beats of classical design. Before I jump into alternative structures and plots I want to make sure we understand arch plot as more than just a template for story. I want to show how this story-frame can be used, and used well.

Today I’m going to breakdown the major beats of classical design using Pixar’s film Toy Story. This film is an excellent example of how arch plot can create a satisfying story experience that moves like a well-oiled machine and every piece has a purpose. Let’s take a look at how the eleven steps outlined in my previous post are put into practice.

ACT ONE:

1) Ordinary World

In the first images of Toy Story we’re introduced to Andy and his favorite toy Sheriff Woody (our protagonist). In the first minutes we establish Woody’s ordinary world, consisting of Andy’s room. At minute four, we get the story hook: the toys come to life. At this point we’re introduced to the major players: Mr. Potato Head, Slinky-dog, Bo-Peep, etc. Relationships are hinted at and we see that Woody is the leader of this clan. The complexity of this world deepens when the first obstacle is introduced, allowing us to see how Woody normally functions in the ordinary world. The obstacle is Andy’s birthday party and a covert toy-style mission to see if there are any new, bigger and brighter, toys to be worried about. This action reveals the emotional core of the film: every toy’s deepest fear is that they will be replaced and Andy will no longer love them. In the first twelve minutes the film has set up the world, how it works, and what’s at stake.

2) The Call to Action

At minute fourteen, Buzz Lightyear shows up on screen. Something new has arrived to disrupt the ordinary world. This is what the hero’s journey calls the call to adventure. In Toy Story the call isn’t an invitation to a quest, but it is a catalyst that disrupts Woody’s status quo. Woody tells himself that this new toy isn’t going to change anything and we enter…

3) The Refusal of the Call

This is the debate section where Woody tries to keep his authority, but is slowly usurped by Buzz.

4) Crossing the First Threshold

Woody’s refusal culminates when his flaws of pride and jealousy cause him to pick a fight with Buzz. Both toys fall out of the car and Andy’s family drives away, leaving Woody and Buzz on the pavement. The two have now become LOST TOYS! This is the moment when Woody and Buzz cross the first threshold and move us into act two. This is the point of no return. Woody and Buzz are no longer in the ordinary world but the special world, which will force them to grow. The energy of the story changes here because the two have a new desire: to get home.

ACT TWO:

5) Tests, Allies, and Enemies

The next seventeen minutes of the film constitutes the fun and games section where our heroes are presented with tests, allies, and enemies. When I went to film school we called this the “trailer section.” It’s where all the gags and jokes used in a film trailer come from. This is the section of the story that fulfills the promise of your premise. Toy Story’s premise is: how do two rival toys find their way home when lost in the real world? Well, they hitch a ride to pizza planet. They get chosen by The Claw and taken home by the evil neighbor Sid. They defend themselves against cannibal toys. Each obstacle gets harder and harder. And it leads us to…

6) The Mid-Point

In the hero’s journey there isn’t actually a mid-point, but in screenwriting it has become very important story beat. It’s where the energy of the film swings up, or swings down. In Toy Story it swings down. Buzz comes upon a TV commercial selling Buzz Lightyear action figures and realizes he is not the Buzz Lightyear, but actually a TOY!

7) Approaching the In-Most Cave

The mid-point also affects Woody and propels the story into the next section. Woody continues to put out fires while Buzz has his existential crisis. This is known as approaching the in-most cave or continued obstacles and intensification.

8) The In-Most Cave

At minute 57, Woody hits rock bottom and reaches the in-most cave or crisis of the story. Both Woody and Buzz are trapped, Woody’s friends have abandoned him, and he can now see that his pride has led him astray.

ACT THREE:

9) The Final Push

Just after the crisis usually comes a change in fate. Sid takes Buzz into the backyard to blow him up and Woody realizes he must save the only friend he has left. This propels us into act three and the final push where Woody devises a rescue plan.

10) Seizes the Sword

Woody enacts his plan in the climax and seizes the sword by saving Buzz’s life!

11) The Return Home

But the return home is still wrought with tension as Woody and Buzz chase down the moving van. Some consider this a second final climax (think horror films where monsters you thought were dead jump out at the last minute). Woody grows by putting his pride aside and works together with Buzz to reunite with Andy. As the film closes Buzz and Woody have returned to the new ordinary world with the wisdom and friendship of their adventure.

This is classic design used well! It creates an emotionally engaging and well-paced story. If you like this story design I highly suggest reading Sheryl Scarborough’s guest post that continues this discussion in regards to three-act structure.

However, despite popular belief, classic design is not the only way to tell a story. My next post will outline the hidden agenda of arch plot and why we need more storytelling options!

From my previous posts outlining the major beats of classic design (aka: arch plot, the universal story, mythic structure, the hero’s journey, etc.) you’ve seen that this design is very precise. If done well this “universal story” creates a satisfying story experience where all the pieces seem to fall effortlessly into place. It’s clean. It’s inspiring. It’s tempting to use such a beautiful template to organize our stories as well. And at first glance – why shouldn’t we? After all classic design is touted as:

From my previous posts outlining the major beats of classic design (aka: arch plot, the universal story, mythic structure, the hero’s journey, etc.) you’ve seen that this design is very precise. If done well this “universal story” creates a satisfying story experience where all the pieces seem to fall effortlessly into place. It’s clean. It’s inspiring. It’s tempting to use such a beautiful template to organize our stories as well. And at first glance – why shouldn’t we? After all classic design is touted as: In his book Story, Robert McKee has the grace to acknowledge other plots, but goes on to point out that a writer must earn a living at writing, and according to him you can’t do that without arch plot because “classical design is a mirror of the human mind.”

In his book Story, Robert McKee has the grace to acknowledge other plots, but goes on to point out that a writer must earn a living at writing, and according to him you can’t do that without arch plot because “classical design is a mirror of the human mind.”  And for Joeseph Campbell (the founder of mythic structure), it turns out he may have had an agenda of empowerment. Bayerl notes that he “became obsessed with the hero’s journey because he was troubled by what he perceived as the despair of his times; he believed that elevating heroic myths would heal the collective psyche. Campbell explains how the hero myth can support healthy psychological growth when people recognize their own problems in the ordeals of the mythic … and are reassured by the stories that give them abundant, time-tested strategies for survival, success, and happiness.” This is exactly what Truby and McKee meant when they said structure can be used as a metaphor for how to live our lives.

And for Joeseph Campbell (the founder of mythic structure), it turns out he may have had an agenda of empowerment. Bayerl notes that he “became obsessed with the hero’s journey because he was troubled by what he perceived as the despair of his times; he believed that elevating heroic myths would heal the collective psyche. Campbell explains how the hero myth can support healthy psychological growth when people recognize their own problems in the ordeals of the mythic … and are reassured by the stories that give them abundant, time-tested strategies for survival, success, and happiness.” This is exactly what Truby and McKee meant when they said structure can be used as a metaphor for how to live our lives. 2) Does it Create a False Sense of Values?

2) Does it Create a False Sense of Values? 5) Does it Perpetuate an Untrue American Myth?

5) Does it Perpetuate an Untrue American Myth?

Great information here on plot and structure. Well done.

Wow, Ingrid. This is awesome. I read OUTLIERS, so I totally get what you’re saying. I admit I blindly followed a story model without asking myself why I chose it. But you’ve given me much to think about. Thanks for doing the hard work here.

Great food for thought! Looking forward to your posts on alternative plot structures. That said, I don’t think that the Hero’s Journey necessarily defines a value system. Couldn’t a “goal” be to achieve wisdom and compassion? This is, in fact, the goal of Buddhist practice. When I started learning about the Hero’s Journey, I was amazed to find that “The Life of Milarepa,” who was a realized master in Tibet, followed the Hero’s Journey to a “T.” Life is struggle and hardship no matter which way you slice it and we all work hard at something and we all learn something from that hard work. We don’t necessarily have to “save the world” but we each must accomplish something in order to make our lives worth living. And of course, the process, the struggle itself, is what teaches us, whatever our stated “goals” may be.

Don’t feel bad about blindly following it. I’d done it for years myself and always wondered why the stories I wanted to tell didn’t fit into this “perfect” model. I kept wondering what I was doing wrong!

Cindy, you bring up great points. And yes, I do think I have simplified things a bit in this post. I actually think that much of the hero’s journey was intended to have the hero discover wisdom as the side effect of the journey, and that the goal was the external impetus for growth. But lately, I’m finding that the wisdom part gets second fiddle (or no fiddle) to the search for the goal.

You absolutely could have a story where the goal is to achieve wisdom and compassion. But I’m finding the argument often is that that type of goal is too abstract and intangible. Of course, I personally would love to see what that story would be about!

You’re the bomb, Ingrid. The archetypal hero’s journey is in our blood, in our cells. As consumers of Story we can’t help but shine that light onto our own struggles and retell them in our writing. But here’s a new struggle: transcending the heroic myth. Where do we go for guidance? To extraterrestrials? To utterly alien cultures? I look forward to your next few posts. I think you’ve excavated some exciting questions and I thank you.

I just love this post. I’ve come back to read it several times. Looking forward to more!