new posts in all blogs

Viewing: Blog Posts Tagged with: ammon shea, Most Recent at Top [Help]

Results 1 - 25 of 30

How to use this Page

You are viewing the most recent posts tagged with the words: ammon shea in the JacketFlap blog reader. What is a tag? Think of a tag as a keyword or category label. Tags can both help you find posts on JacketFlap.com as well as provide an easy way for you to "remember" and classify posts for later recall. Try adding a tag yourself by clicking "Add a tag" below a post's header. Scroll down through the list of Recent Posts in the left column and click on a post title that sounds interesting. You can view all posts from a specific blog by clicking the Blog name in the right column, or you can click a 'More Posts from this Blog' link in any individual post.

By: Alice,

on 8/4/2014

Blog:

OUPblog

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

Books,

Literature,

shakespeare,

ammon,

shea,

OWC,

ammon shea,

charlie,

Oxford World's Classics,

durrell,

king lear,

lear,

bryant,

Bryant Park,

Humanities,

*Featured,

Bryant Park summer reading,

novobatzky,

couresty,

Add a tag

Each summer, Oxford University Press USA and Bryant Park in New York City partner for their summer reading series Word for Word Book Club. The Bryant Park Reading Room offers free copies of book club selections while supply lasts, compliments of Oxford University Press, and guest speakers lead the group in discussion. On Tuesday 5 August 2014, Ammon Shea, author of Reading the OED and Bad English, leads a discussion on Shakespeare’s King Lear.

What was your inspiration for Bad English?

What was your inspiration for Bad English?

I am often guilty of spectacular incompetence when I try to use the English language, and I wanted to find some justification for my poor usage. I am happy to report that we have all been committing unseemly acts with English for many hundreds of years.

Where do you do your best writing?

In library basements, preferably when they are empty of people.

Did you have an “a-ha!” moment that made you want to be a writer?

I hadn’t so much of an ‘a-ha’ moment that made me want to be a writer as I had a series of ‘uh-oh’ moments while doing other things that did not involve writing.

Which author do you wish had been your 7th grade English teacher?

Gerald Durrell

What is your secret talent?

I can distinguish between Sonny Stitt and Charlie Parker, and between Phil Woods and Gene Quill, in under four measures.

What is your favorite book?

Too Loud a Solitude by Bohumil Hrabal.

Who reads your first draft?

My wife reads my first drafts, and, if she is feeling particularly generous, my second and third ones as well.

Do you read your books after they’ve been published?

Not unless I absolutely have to.

Do you prefer writing on a computer or longhand?

I have no marked preference. I will write on whatever is at hand, and this ranges from cellular telephones to antiquated typewriters.

What book are you currently reading? (And is it in print or on an e-Reader?)

Charlie and the Chocolate Factory, with my son, and in print.

What word or punctuation mark are you most guilty of overusing?

I reject the premise of this question.

If you weren’t a writer, what would you be?

Someone who wished he was a writer.

Ammon Shea is the author of Bad English, Reading the OED, The Phone Book, Depraved English (with Peter Novobatzky), and Insulting English (with Peter Novobatzky). He has worked as consulting editor of American dictionaries at Oxford University Press, and as a reader for the North American reading program of the Oxford English Dictionary. He lives in New York City with his wife (a former lexicographer), son (a potential future lexicographer), and two non-lexical dogs.

For over 100 years Oxford World’s Classics has made available the broadest spectrum of literature from around the globe. Each affordable volume reflects Oxford’s commitment to scholarship, providing the most accurate text plus a wealth of other valuable features, including expert introductions by leading authorities, voluminous notes to clarify the text, up-to-date bibliographies for further study, and much more. You can follow Oxford World’s Classics on Twitter and Facebook. Read previous interviews with Word for Word Book Club guest speakers.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only literature articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Image couresty of Jenny Davidson.

The post 10 questions for Ammon Shea appeared first on OUPblog.

By: Rebecca,

on 11/18/2009

Blog:

OUPblog

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

word of the year,

corpus,

unfriend,

NOAD,

language,

A-Featured,

Lexicography,

Dictionaries,

A-Editor's Picks,

english,

oed,

ammon shea,

Add a tag

Ammon Shea is a vocabularian, lexicographer, the author of Reading the OED: One Man, One Year, 21,730 Pages and a frequent OUPblog contributor. In light of our Word of the Year 2009 announcement (WOTY) Ammon has taken a closer look at how WOTY is chosen. In the post below he reveals the process that led to unfriend being chosen as WOTY 2009.

Every year, at about this time, the New Oxford American Dictionary releases its Word of the Year (WOTY), a combination of solid lexicographic practice and a light-hearted look at the changing face of English today. Since there are quite possibly thousands (or at least dozens) of people out there who wonder “where does the Word of the Year come from?” the following is a brief explanation of what this momentous process entails, and what it does not.

You could be forgiven for thinking that the Word of the Year is chosen by a group of unruly lexicographers, drunk on whimsy and an inflated sense of their own power, who are hell-bent on introducing silly words into English. So let’s see what actually happens.

The candidates for WOTY are drawn from three main sources, each of which reflects a particular strength of Oxford University Press and its unrivaled language research program. The first of these is the Oxford English Corpus, a database of over two and a half billion words drawn from current English the world over. The corpus is fully searchable, allowing the editors to find words that have either entered the language or changed meaning significantly enough to warrant attention. The use of the corpus allows tracking of words, and the examination of the shifts that occur in geography, register, and frequency of use.

The second body of candidates to merit consideration for the WOTY is composed of those that have been “catchworded” (catchworded words are those that have been identified as new or unusual usages by one of the vast number of readers who provide citations of word use for the OED and other Oxford Dictionaries). An editor who is responsible for new words in English combines the catchworded items into a digital database, a sort of mini-corpus, in which individual words can be analyzed by frequency, register, and region.

The third source for potential Words of the Year comes from the various editors at OUP, who are continually keeping tabs on the varieties of English and the ways in which these varieties are changing. These words come from the editor’s own reading, or from conversations they’ve had, and from lists of new words that are taken from one of the numerous dictionaries published by OUP.

Once the preliminary list of words has been collected it is sent to a group of perhaps 7 or 8 editors, who commence poking at the words with a sharp stick, weeding out those that aren’t in fact new, or which may new, but not yet widespread enough to be more than a regionalism. The words are all checked to make sure that they do not exist in any current dictionary, and that there is sufficient evidence in the Oxford English Corpus, in various forms of print, and on internet search engines to warrant each one’s inclusion.

This list of words is sent around and winnowed to a short list, which is then itself winnowed to a final list, and from the final list a single word is chosen which has been accorded the honor of being the Word of the Year.

Although the process of picking the WOTY is quite similar to that of introducing a word into a dictionary, this status does not guarantee that the word will be included in any future reference works. The word in question may be quite widespread today and have fallen entirely from use within a few years. The WOTY is not a popularity contest, nor is it simply the word that has been used more than any other over the past year. It is a forward-looking examination of one small aspect of our language, one in which the Oxford lexicographers take a chance on picking the word that they think represents the use of language today, and that will continue to have an influence.

It can be a tricky business, trying to figure out which words will stick ahead of time, and there is no shame in making an educated guess that turns out to not be as accurate several years hence as it seems now. James Murray famously decided to leave the word appendicitis out of the first edition of the Oxford English Dictionary after receiving advice from William Osler (a famous doctor at Oxford) that it was likely not a word that would ever be in widespread use. A short time later the coronation of Edward VII was delayed after he had to undergo an emergency operation for his appendicitis. Although many people wondered why the word was not in the OED, there was no way that Murray could have made the necessary guess to include it.

The WOTY is an attempt to capture some of the breathtaking fluidity of our language, and to look at its semantic change and inventiveness in real time, through the use of solid research, editorial skill, and intuitive guesswork.

By: LaurenA,

on 10/29/2009

Blog:

OUPblog

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

Reading,

Reference,

the,

Historical,

Oxford,

A-Featured,

Lexicography,

Dictionaries,

of,

English,

oed,

oxford english dictionary,

Dictionary,

Ammon,

Shea,

Thesaurus,

ammon shea,

Reading The OED,

Historical Thesaurus of the Oxford English Dictionary,

HTOED,

Add a tag

Lauren, Publicity Assistant

Ammon Shea is a vocabularian, lexicographer, and the author of Reading the OED: One Man, One Year, 21,730 Pages. In the videos below, he discusses the evolution of terms like “Love Affair” and names of diseases, as traced in the Historical Thesaurus of the Oxford English Dictionary, demonstrating how language changes and reflects cultural histories. Shea also dives into the HTOED to talk about the longest entry, interesting word connections, and comes up with a few surprises. (Do you know what a “strumpetocracy” is?) Watch both videos after the jump. Be sure to check back all week to learn more about the HTOED.

Love, Pregnancy, and Venereal Disease in the Historical Thesaurus

Click here to view the embedded video.

Inside the Historical Thesaurus

Click here to view the embedded video.

By: Rebecca,

on 6/4/2009

Blog:

OUPblog

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

Reference,

Education,

conference,

A-Featured,

Lexicography,

Dictionaries,

dictionary,

ammon shea,

hiatus,

Dictionary Society of North America,

Add a tag

Ammon Shea recently spent a year of his life reading the OED from start to finish. His book, Reading the OED, has been published by Perigee, so go check it out in your local bookstore. In the post below Ammon reports on the Dictionary Society of North America Conference.

I spent four days last week sitting in a mildly uncomfortable chair and experiencing the distinct pleasure that comes from listening to people far more knowledgeable than I speak on the subject of dictionaries. It was the biannual meeting of the Dictionary Society of North America, held at Indiana University, in Bloomington, and although I learned an enormous amount, I have to confess that there is one question from my time there that still plagues me – why don’t more people go to conferences?

To be more specific about this query, I mean that I don’t quite understand why more people who are not connected with lexicography, linguistics, or some related field do not attend this meeting. I routinely meet people who say they are enchanted by dictionaries, and have questions about how they work and their history, what better way to indulge one’s interest in a subject than to go where you are surrounded by dozens of experts in a field?

Granted, this is not the typical holiday that comes to mind for most, and I guess that is reasonable. But I did see a few attendees, such as my friend Leonard Frey, whose interest in dictionaries is purely amateur (in the best sense of that word), and who drove up from Memphis with his wife. Their obvious enjoyment was so pure and infectious that it constantly reminded me how lucky I was to attend. Among the highlights:

Kate Wild, of the University of Glasgow, gave a talk on re-assessing Samuel Johnson’s usage labels that forever changed the way I’ll read that dictionary. Grant Barrett demonstrated an impressive and potentially enormously productive use of Amazon Turks in creating a database of user-created definitions. And Sarah Ogilvie showed that scholarship and sustaining audience interest need not be mutually exclusive, in a paper that effectively made the case that, while James Murray was certainly one of the greatest lexicographers in history, he was also prone to inordinate bursts of peevishness and paranoia.

However, the greatest enjoyment came from listening to the editors of the Historical Thesaurus of the OED, especially Christian Kay and Irené Wotherspoon (who between them have close to 80 years experience working on that magnificent project). I’ve mentioned the HTOED before, and feel no compunction to avoid repeating myself. If you have any curiosity about the English language go buy yourself a copy – it is not cheap by any means, but no matter the price it is a bargain. And I can imagine no better advocates for it than Kay and Wotherspoon, who exude intellectual grace and humor like few I’ve ever seen. If they decided to write a book on the history of Popsicle sticks and watch fobs I would run out and buy it.

On a side note, I will be taking a hiatus from this blog for the next three months, while I finish a book. See you all again soon.

By: Rebecca,

on 5/14/2009

Blog:

OUPblog

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

words,

A-Featured,

Dictionaries,

oed,

dictionary,

Prose,

ammon shea,

bhalla,

I'm Not Hanging Noodles on Your Ears,

Add a tag

Ammon Shea recently spent a year of his life reading the OED from start to finish. Over the next few months he will be posting weekly blogs about the insights, gems, and thoughts on language that came from this experience. His book, Reading the OED, has been published by Perigee, so go check it out in your local bookstore. In the post below Ammon looks at I’m Not Hanging Noodles On Your Ears.

I don’t know what the collective noun is for master’s degrees, but I would like to propose that we consider bhalla as a possibility. The reason for this is that I’ve recently had the opportunity to read a delightful book on idioms written by a man named Jag Bhalla, and he has five of them.

This curiously named work, I’m Not Hanging Noodles On Your Ears, is an exploration of over 1,000 idioms in ten languages, collected by Bhalla over the course of what must have been extremely extensive travel. This is not an academic work (and I mean that only in the sense that it is not at all boring), but it is enormously educational.

Hanging Noodles is divided thematically, and the chapter headings were enticing enough to make me immediately want to skip ahead (I think far more writers should follow Bhalla’s example, and use titles such as ‘Give it to someone with cheese’ or ‘Swallowed like a postman’s sock’). Each of these chapters is comprised of an essay on a particular aspect of language, followed by a list of pertinent idioms.

I’ve long thought that books on language and words shared some characteristics with travel books. At their best they have the capacity to be transporting, to make some part of your reading brain feel as though it might be in some other place or time. This book transported me, in the senses that I felt able to travel to other places and also in that I utterly lost several afternoons to reading it. The writing is adroit, the subject fascinating, and the execution impeccable.

The only quibble I have with it is that Bhalla is his habit of being overly deferential to the many other writers whose work he discusses. It’s certainly not the case that I think that David Crystal and Stephen Pinker are undeserving of praise, but too often their names are prefaced panegyrically, which makes Bhalla appear slightly uncertain. He needn’t be – Hanging Noodles is a delightful book, and well worth getting yourself lost in.

By: Rebecca,

on 4/30/2009

Blog:

OUPblog

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

book,

digital,

A-Featured,

future,

Dictionaries,

kindle,

Online Resources,

oed,

ammon shea,

unloved,

libraries,

Add a tag

Ammon Shea recently spent a year of his life reading the OED from start to finish. Over the next few months he will be posting weekly blogs about the insights, gems, and thoughts on language that came from this experience. His book, Reading the OED, has been published by Perigee, so go check it out in your local bookstore. In the post below Ammon looks at the future of the book.

There is a good deal of discussion and arguing going on regarding the apparently perilous state of the physical object known as the book. Some factions view Google’s attempt to scan the world’s libraries as a boon, and others see it as a rather naked power grab that will have dire consequences for authors and their audiences. Some individuals have embraced the Kindle, some have sworn to never sully their eyes on such a thing, and still others have never heard of it. Some are of the opinion that all print that has ever been committed to paper deserves to be preserved, and others point out that we publish more books now than ever before, and surely some of it is not worth saving. I am of varied opinion on all these things.

However, amidst all this rancor and debate, I feel that there is one type of book that is all too often not taken into account, and that is the book about which very few people care. It may seem counter-intuitive, but I believe that it is precisely because so few people care about these books that they should be kept around.

One of my favorite browsing books of late is a volume titled (with an utter lack of irony) Toys That Don’t Care, by Edward M. Swartz, published in 1971. It is an expose of the children’s toy industry, which, by the way, did indeed produce some horrific things for infants to play with back in the 1960’s. Unintentionally hilarious, it details a range of games and toys that clearly exhibit both changing social mores and standards of safety (such as the toy hypodermic needle with the slogan “Hippy-Sippy says I’ll try anything”, and a board game titled “Pieces of Body”).

The book itself is fairly strident, not terribly well written, out of print and extremely out of date. And I’ve noticed that most of the libraries near me that still have a copy have relegated it to the offsite storage facility. It gave me a good deal of enjoyment when I found it on a library shelf, and I hate to think of books such as this falling through the cracks. They are not bad enough to be produced in enormous quantities, and so survive through sheer force of numbers. And they are not good enough to have a team of supporters crying out for their preservation. But this particular absurd book, and many others just as mid-level, and going to be enjoyed by someone, provided that they can be found on a shelf.

And so, undaunted by any actual knowledge of how the library sciences work, and what influences the decision of whether to send a book offsite of not, I have resolved to spend more time searching through the basement shelves of libraries, seeking out those perhaps unworthy and certainly unloved books that are waiting to be found by someone, and to borrow these books, in the vain hope that by keeping them in the system as ‘books that are borrowed’ I can in some way forestall their inevitable relegation to the dustbin of storage.

Ammon Shea recently spent a year of his life reading the OED from start to finish. Over the next few months he will be posting weekly blogs about the insights, gems, and thoughts on language that came from this experience. His book, Reading the OED, has been published by Perigee, so go check it out in your local bookstore. In the post below Ammon looks at how many words are in the English language.

I was contacted recently by a journalist who is writing a story about the claim that the size of the English language is feverishly approaching one million words. This claim has been promulgated with varying degrees of self-righteousness over the past few years by a fellow who seems to be armed with little more than a purported algorithm and an inflated sense of importance. The notion of ‘one million words of English’ has been debunked by others who are far more educated than I (Ben Zimmer, Jesse Sheidlower, Geoffrey Nunberg), so I’ll not waste time in addressing it, except to note that calling it clap-trap would be unfair to the clap.

Yet it does make me wonder – why is it that we are so often interested in putting a number on something as inherently unquantifiable as vocabulary? The journalist who was writing the story was an educated and interesting person, and seemed genuinely curious about the subject. I wish that I’d had better answers for her but I can think of few things about which I have less knowledge than how many words our language has, and how many of them I (or anyone else) might know. I might as well be asked to state how many memories a person has.

I don’t mean to imply that this is not an area that deserves serious study; it obviously does, and there is a great deal of research done by linguists on many types of language acquisition (the phrase ‘vocabulary size’ yields approximately 11,000 results on Google Scholar). But there are so many awkward examples of people trying to come up with a sure-fire measurement for things such as the exact size of an average person’s vocabulary, or the total number of words in a language; the one commonality in these attempts seems to be a marked disparity.

There appears to be a certain degree of difficulty in ascertaining what a word is, at least for purposes of counting (is set one word or hundreds, do regional variants count as additional words, are obsolete terms to be counted?). Similarly, there seems to be no easy way to judge what it means to say that someone ‘knows’ what a word means – do they have to be able to define it, to know how to spell it, or can they pull a Potter Stewart, and simply ‘know it when they see it’?

I was thinking of all this today as I rode my bicycle through New York City traffic, trying to decide whether the word what would be one word or many, and how I would define it if I were so queried. I accomplished nothing except to give myself a headache, a near miss with a large truck, and a resolve to leave the counting of words to professionals, who are smart enough to stay away from algorithms.

By: Rebecca,

on 4/2/2009

Blog:

OUPblog

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

work,

Business,

jobs,

words,

A-Featured,

Dictionaries,

oed,

ammon shea,

intern,

interning,

Add a tag

Ammon Shea recently spent a year of his life reading the OED from start to finish. Over the next few months he will be posting weekly blogs about the insights, gems, and thoughts on language that came from this experience. His book, Reading the OED, has been published by Perigee, so go check it out in your local bookstore. In the post below Ammon looks at the role of interns.

I often spend some portion of the day looking through job listings, as I suspect do many people who are in the habit of attempting to make a living as a writer (or most other things these days). Two things have struck me – that I never get a response to the query letters I send out, and that the meaning of the word intern appears to have broadened somewhat.

Most dictionaries define intern as an advanced student, usually in the fields of medicine or teaching, who is receiving instruction through performing certain tasks under supervision in a workplace. If one were to write a new definition, based on the usage of the word as it appears in craigslist and various other sites, the meaning would perhaps be closer to ‘unpaid worker.’

I am certain that many of the internships advertised are being offered by individuals or institutions who have nothing but the best intentions in mind, and who want naught but to further the careers and opportunities of the youth of today, beset as they are by a difficult job climate. But what of the one I saw this morning that made no mention of such frivolity as ‘mentoring’ or ‘guidance’, and whose responsibilities included providing financial analysis, budget and strategic planning, and developing presentations for senior management, among other things. Is this truly an internship?

Perhaps I’m being naïve about all this, but while I’m sure that some employers have always looked for free or cheap labor I cannot help but think that it is getting worse. Several weeks ago there was an ad looking for an intern who could dress nicely, provide childcare, answer phones, lift some boxes, write and edit stories, and was fluent in French. And if this wasn’t too much to ask for ten dollars a day the writer of the ad further specified that the French must be of the Parisian sort.

There is a literary agency currently taking the rather imaginative angle of presenting their work as a chance to grow – “The position” (which happens to be an unpaid one) “also offers the opportunity to read and evaluate both fiction and non-fiction manuscripts”. I wonder if it also offers the opportunity to sweep hallways and empty trash bins?

This is all beginning to remind me of the scene form The Adventures of Tom Sawyer, in which Tom wriggles out of white-washing a fence by convincing all the boys who pass by that this is a great opportunity for fun. Taking the bait, the neighborhood kids end up offering to pay for the chance to paint the fence, and by the end of the day Tom has a job that has been done for him and has also managed to accumulate a great pile of goods, including, but not limited to, part of an apple, a kite, twelve marbles, a spare key, a bit of chalk, a one-eyed kitten, and “a dead rat and a string to swing it with.”

Which gives me an idea – the next time I send out my query letters looking for work I’ll remember to include the dead rat.

By: Rebecca,

on 3/12/2009

Blog:

OUPblog

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

quirky,

reading death,

Obituaries,

details,

A-Featured,

Media,

oed,

ammon shea,

newspaper,

Add a tag

Ammon Shea recently spent a year of his life reading the OED from start to finish. Over the next few months he will be posting weekly blogs about the insights, gems, and thoughts on language that came from this experience. His book, Reading the OED, has been published by Perigee, so go check it out in your local bookstore. In the post below Ammon shares his love of the obit section.

I am an unabashed fan of trivial information. I suppose this may rightfully be referred to as trivia, but I prefer the adjectival word to the plural noun – trivia has a limited range of meaning (each of which is more or less contemptuous), whereas trivial can refer to things having to do with math, chemistry, mediæval university studies, the place where three roads meet, and a host of other subjects. The trivial does not provide grand explanations for why the world is so, but it tells some small piece of history as a story, and in doing so grabs my attention in a way that great events never seem to. I suppose this is why I enjoy reading obituaries.

I find the obituaries to be by far the most interesting part of the newspaper. Not because I have a morbid fascination with death, but because this is where wonderful little details come out, things that would ordinarily not be classified as news. Yesterday I was reminded of one of my favorite obituaries of recent years, from the New York Times of September 12, 2008, titled “Martin K. Tytell, Typewriter Wizard, Dies at 94”.

It is a long obituary, and justifiably so, for even though it deals with (mostly antique) typewriters, the man it profiles was the foremost expert of this field, and deserves the column inches. It is a fascinating story, full of intrigue (Alger Hiss and the O.S.S.) and descriptions of a man who was entirely devoted to his field. Somewhere near the middle there a nugget of trivia, mentioned almost in passing: “An error he made on a Burmese typewriter, inserting a character upside down, became a standard, even in Burma.” I cannot help but wonder what the typewriter wizard’s feelings were on this – was he chagrinned at his mistake, or satisfied in a quiet fashion that his influence was such as to change a written language?

This has been on my mind of late because a friend has recommended a book on the subject: The Dead Beat, by Marilyn Johnson, a former obituary writer. I’ve not yet had the chance to read it, but it has the twin virtues of featuring a fine, under-written subject and possessing a great opening line: “People have been slipping out of this world in occupational clusters, I’ve noticed, for years.”

I wish that there were more of this in the news. It is not that I want to ignore the ugliness and strife of the world, and I am not calling for more feel-good human-interest stories in the news, but why must the unimportant yet interesting details wait until a person is dead before they can be widely known? It seems odd that death grants the permission to make the whimsical newsworthy.

By: Rebecca,

on 3/5/2009

Blog:

OUPblog

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

Library,

books,

Literature,

Reference,

librarians,

worldcat,

A-Featured,

Dictionaries,

ammon shea,

storage,

offsite,

Add a tag

Ammon Shea recently spent a year of his life reading the OED from start to finish. Over the next few months he will be posting weekly blogs about the insights, gems, and thoughts on language that came from this experience. His book, Reading the OED, has been published by Perigee, so go check it out in your local bookstore. In the post below Ammon discovers the wonder of librarians.

Last week I wrote about some of the frustrations I have with libraries and the burgeoning practice of moving items to offsite storage, and I am afraid that what I wrote may have unintentionally come across as a condemnation of librarians and/or library science. After speaking with some librarians about the subject it seems rather clear that they regard offsite storage, at best, as a necessary evil. And although my evidence is purely anecdotal, I also had an impression that there is some disagreement between library staffers and library administrators as to answer the question of what should be moved offsite when there simply isn’t enough room at the library.

The question of what to send offsite is not one that has an easy answer. I asked at several libraries what the policy was for deciding which items stay and which go offsite and found that there wasn’t a great deal of consistency among them; different facilities base their decisions on different criteria. One thing was fairly consistent, and that was that every one said that the frequency with which an item was used played a large part in the decision.

On the face of it this would seem to be a logical thing – it is far more practical to keep a book that is used frequently than to keep a book that is used once every decade or two. And some libraries, particularly those of academic institutions, have a responsibility to their users to keep more germane materials at hand. But do all libraries have to be practical?

Aside of the fact that by moving obscure items offsite and rendering them unbrowsable you are condemning them to a further self-perpetuating cycle of obscurity, I have another problem with this practice – if all our libraries focus on primarily keeping books that are used frequently there is a risk of homogenization. It may well be impractical, but I am of the opinion that the potential of serendipitous discovery of some delightful and strange old book should play as large a part in deciding what to keep as frequency of usage.

I have a feeling that I am crankier about this than the average person, most likely because I’ve spent the past few months looking for books and periodicals in libraries which have all been sent offsite. And so I’ve spent far more time this year talking with librarians than I have in previous years. This has led to a startling discovery, which is that I know very little about both libraries and librarians.

I’ve long thought of myself as pretty library-savvy, and certainly not the kind of person who needs to spend a good deal of time pestering the librarians with questions. I can remember the flush of satisfaction I felt when I first came across worldcat.org, and thought that I could now effortlessly find any book in any library in the world. It turns out that I was in a fairly advanced state of ignorance, one in which I didn’t even know what I didn’t know.

For instance, worldcat does not have a complete list of all the books in all libraries. It is a magnificent resource, I use it all the time, and it has attained the status of being one of those few things in my life that I feel are indispensable. But it is not complete. My understanding is that libraries have to pay a fee to have all their holdings listed in worldcat, and some smaller or underfunded libraries are either unable or unwilling to do this. Does this mean that their holdings cannot be found? Not at all – they can be found in another catalogue, called the OCLC, but you need a librarian for that.

I receive a great deal of joy from discovering my ignorance, provided that it is concurrent with discovering someone who has the means of enlightening me. And so recently I’ve had a wonderful time finding out how much I don’t know about libraries, courtesy of a number of reference desk librarians. I’m simultaneously delighted to have been made aware of how knowledgeable and helpful these people are and terribly dispirited that I’ve already spent so much time in libraries without availing myself of their help.

Perhaps most of you who read this already know all about the esoteric abilities of the reference librarians, in which case you can scoff at boors like me, whose typical scope of questions ranges from “where are the restrooms?” to “how late are you open?”. But I’m willing to bet that most library patrons are not-so-blissfully unaware of how limited their library experience has been. In the past few months I’ve been given passes to private libraries to which I don’t belong, had books found that I thought no longer existed, had things looked up for me hundreds of miles away, gotten tutorials in how to research far more efficiently, and received answers to dozens of questions that I didn’t even know I had yet.

It reminds me of when I finally realized that the dictionary is so much more than just a book of definitions – reference desk librarians are the etymologists, the orthoepists, and the collectors of citations of the library.

By: Rebecca,

on 2/26/2009

Blog:

OUPblog

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

libary,

Reference,

digital,

A-Featured,

Dictionaries,

dictionary,

ammon shea,

oed,

storage,

periodicals,

Add a tag

Ammon Shea recently spent a year of his life reading the OED from start to finish. Over the next few months he will be posting weekly blogs about the insights, gems, and thoughts on language that came from this experience. His book, Reading the OED, has been published by Perigee, so go check it out in your local bookstore. In the post below Ammon looks at modern libraries.

I spend a good deal of time wandering around in libraries. Some of this time is distinctly productive – I’m looking for something specific. But much of my time is spent simply browsing; engaged in the occasionally vain hopes that I’ll find something of interest, and content in the knowledge that I’ll enjoy myself whether I do or do not.

The inexorable progress of library science, however, seems to not take browsing into consideration much when planning how to improve libraries, and there is an increasing rush to move holdings into ‘offsite storage’, a term that I feel has a decidedly euphemistic ring to it. I’m not particularly interested in having a debate with a horde of tetchy librarians about what is the best way for them to perform an admittedly difficult job, but I had an experience last week that made me think of offsite storage in a new(ish) light.

I pay for a visiting library membership at an Ivy League institution near where I live, and while it is not terribly cheap I certainly consider it money very well spent. Their libraries are beautiful and august things, impeccably maintained, filled with gorgeous books and a staff that is well-informed and helpful. But although they have enormous holdings, they are increasingly moving them to a warehouse in New Jersey. It is not an onerous process to look at something that has been moved offsite – you just fill out a form, and the requested item arrives in a day or two. This is an efficient system for many things, but not for browsing. Browsing does not work in two day intervals. It feels like playing chess by mail, a game that has never appealed to me.

Until recently I’ve not been so upset about this system. But then I found that they didn’t have a periodical I was looking for, and so went up to the library one of the local public colleges to find it, and found that my feelings on offsite storage took a distinct turn towards umbrage.

This library was housed in a huge and unlovely building. My immediate impression upon entering was not good - should an academic institution absolutely have to play music loudly over loudspeakers just outside the library, Iron Man, by Ozzy Osborne and Black Sabbath is an odd choice. My following impressions were in a similar vein – it was filled with students talking loudly on cell phones, there was a blinking fluorescent light in one corridor and a broken fan duct in the next that whined persistently. And there were other delightfully antagonistic touches sprinkled about, such as the two metal triangular shapes protruding from a wall near a water fountain, just high enough to function as seats, which had metal spikes welded onto them, in case anyone had the idea of sitting there.

But all of this was immediately forgotten as soon as I walked down to the basement, where the things I was looking for were kept. The basement stretched on and on, a giant room full of journals, magazines, and periodicals, most of which appeared to have not been looked at for decades. Hundreds of bookshelves covered in dust and groaning under the weight of ignored knowledge. I was suddenly in heaven, albeit a heaven with bad lighting and largely populated with college students talking loudly.

The chances are very great that I will never really need to look through all the issues of The Journal of Calendar Reform or The Transactions of the American Foundrymen’s Association, but I find an indefinable pleasure in coming across them. The run of Crelle’s Journal from the 1820’s to the present is doubly incomprehensible to me, as it is about math and written in German, but it is nonetheless beautiful to look at, with its variegated and marbled covers, and I’m sure that sooner or later someone for whom it is not incomprehensible will come across it there, and be surprised and pleased to find it.

I found the periodical I’d come for, and made copies of it. And I came back to that library the next day and wandered for hours. The volumes are all arranged alphabetically, and I started at A and walked slowly through, looking at every title without taking anything down from the shelves. After an hour of this I had just reached B, so I allowed myself to aimlessly stroll through the stacks, pulling down things whenever they sparked interest. I found lovely illustrations in Aero Magazine from 1937, strange and horrific ways of making recipes with war-time rations in the Journal of Home Economics from 1943, and dozens of other things I’d never thought to look for. I left four hours later, inexplicably happy, covered in dust and bits of knowledge I’ll never understand.

I cannot help but to find it strange that making a physical object inaccessible is now seen as a sign of progress.

By: Rebecca,

on 2/12/2009

Blog:

OUPblog

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

A-Featured,

Lexicography,

Dictionaries,

oed,

dictionary,

Finance,

ammon shea,

word origin,

stimulus,

stimulator,

stimulatrix,

Add a tag

Ammon Shea recently spent a year of his life reading the OED from start to finish. Over the next few months he will be posting weekly blogs about the insights, gems, and thoughts on language that came from this experience. His book, Reading the OED, has been published by Perigee, so go check it out in your local bookstore. In the post below Ammon looks at the word “stimulus”.

I wonder if I am the only one who finds it humorous that the word stimulus is derived from a Latin word that means ‘a goad for driving cattle’ (at least that’s what Skinner’s Origin of Medical Terms says). The OED doesn’t seem to fully agree with Skinner on this, stating in their etymology ‘Originally a mod.L. use (in medical books) of L. stimulus goad, of doubtful origin; perh. f. root *sti- in stilus’.

Is it possible that Henry Alan Skinner foresaw the future use of stimulus as a word that would be tied to our current massive financial package, and thought to include the bit about ‘driving cattle’ in his etymology as a way of expressing his contempt for either the members of congress who will vote for the bill, the bankers who are crying out for its passage, or the public who doesn’t fully understand it (but who incessantly talk about it anyway)? I don’t know what Skinner’s political leanings were, but this seems unlikely, as his book was published in 1949.

No matter what its roots are, no one can deny that the word is really enjoying its time in the limelight. One can hardly begrudge it, as stimulus has not has the most glamorous career in our language. It entered our language in 1684, and its various senses over the centuries have mainly been of the medical or scientific variety – good workmanlike words, but nothing that anyone would get too excited about. It is not the oldest of its family in English - stimulator and stimulatrix, for instance, both appeared some 70 years earlier.

But whether it has a noble pedigree or an exciting definition is beside the point; we are privy to watching a word shift and take on new meaning before our eyes, and that should be interesting enough. For instance, there is only one instance of the phrase stimulus package in the entire OED (it comes, delightfully enough, in the citations for the entry on misgauge). But the New York Times has used this particular phrase over 400 times in the past three months, and I am certain that it is not going away any time soon.

Stimulus will unintentionally be used incorrectly by those people (myself included) who don’t understand exactly what all the billions and trillions of dollars are supposed to do. It will intentionally be used incorrectly by those who want to influence the political fate of the stimulus package. It will be used in ways that are relatively foreign to how it has been used before, in ways that will only be judged correct or incorrect in the future. And possibly some of these new usages and meanings will stick to it, and will be documented in dictionaries to come.

Even if the word is, as the OED claims, of doubtful origin, I am sure that its parents are very proud.

By: Rebecca,

on 12/11/2008

Blog:

OUPblog

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

Library,

History,

book,

language,

A-Featured,

Lexicography,

Dictionaries,

Media,

oed,

best sellers,

ammon shea,

Add a tag

Ammon Shea recently spent a year of his life reading the OED from start to finish. Over the next few months he will be posting weekly blogs about the insights, gems, and thoughts on language that came from this experience. His book, Reading the OED, has been published by Perigee, so go check it out in your local bookstore. In the post below Ammon looks at best sellers throughout history.

months he will be posting weekly blogs about the insights, gems, and thoughts on language that came from this experience. His book, Reading the OED, has been published by Perigee, so go check it out in your local bookstore. In the post below Ammon looks at best sellers throughout history.

With the putative literary recrudescence of Sarah Palin and Joe the Plumber it is quite difficult (perhaps impossible) to make the case that we, as a book-reading people, are becoming more educated. And I have no intention of making that claim, but I have long had the suspicion that no matter how bad things appear now, chances are they used to be similarly bad.

I recently went to the library and looked in the section where they keep the books about the history of best sellers – which sadly enough seem to never quite achieve best-sellerdom themselves. I wanted to have a quick look at what books have apparently so moved the American public of the vaunted past that we bought a great number of them. There are quite a few works dealing with this subject, and most of them are far too trenchant or polemical for my tastes. I was (and remain) far more interested in shoring up some pet theory than in doing actual research. So I passed over books such as 80 Years of Best Sellers (1895-1975), and Making the List – A Cultural History of the American Bestseller.

Then I found a dusty little book from 1947 by Frank Luther Mott, which had the engaging and slightly unseemly title of Golden Multitudes – The Story of Best Sellers in the United States, and it fit the bill perfectly. It had several appendices in the back that gave a nice, succinct account of those books that were ‘best sellers’, and also those that were merely ‘better sellers’.

I turned to the best sellers of yore, searching for clues about our national literary character. And I should add that by yore I mean ‘some time around 100 years ago’, because I thought this was the meaning of the word that would best suit the case that I wanted to make. And as almost always happens when I set out to prove one of my pet theories, I failed.

The best sellers of a hundred years ago cannot hold a candle (or much of anything) to the worst of the bookish excrescences of our day. That’s the bad news. But the good news, in a way, is that these long-ago best sellers seemed to be of an exceedingly ephemeral nature – therefore I think there is no reason to believe that the dreck we publish today will have any more of a half-life than that of its predecessors.

For every title listed that I recognize, such as The Call of the Wild, there are a half dozen more that I’ve never heard of. It is entirely possible that this says more about my own lack of education than it does about the fugacity of our taste, but I have a feeling that there are not so many people today, educated or not, who are sitting about mourning the lack of attention being paid to books such as Freckles (Gene Stratton Porter), Mrs. Wiggles of the Cabbage Patch (Alice Hegan Rice), and Graustark (George Barr McCutcheon). These were all best selling books at the beginning of the twentieth century, at least according to the author of Golden Multitudes.

As I sit here and examine these appendices of the books our nation has loved (or at least purchased in great quantities) over yore and then some, I cannot help but think that there have indeed been some periods more fruitful than others. The 1780’s saw best-sellerhood for Samuel Richardson, Robert Burns, and Alexander Hamilton, all of whom have stood some sort of test of time. And the 1840’s were a fruitful time for Dickens and Dumas, Thackeray and the Brontë sisters, worthies all.

But what of the 1860’s, which saw a proliferation of best sellers by authors with heavily initialized names and largely forgotten books? Mrs. A.D.T. Whitney scored great success with Faith Gartney’s Girlhood in 1863. Not to be outdone, Mrs. E.D.E.N. Southworth one-upped her with a fourth initial, and two-upped her with best sellers, hitting the charts three times in the decade, with The Fatal Marriage, Ishmael, and Self-Raised.

I am going to propose a moratorium on teeth-gnashing about soon to be published books ostensibly written by, or with, failed and minor political figures. If this phenomenon truly bothers you, there are a large number of formerly best selling books that are likely quite good, and are begging for some renewed attention. Pick up a copy of something by A.D.T. Whitney or E.D.E.N. Southworth, and maybe Joe the Plumber’s book won’t even dent your consciousness when it is released.

If you are feeling particularly adventurous your can turn your gaze even further back, to the best seller lists of our country before it was even our country. The author of Golden Multitudes assures me that in the 17th century the book charts were ruled by Michael Wigglesworth. Not only did he have a best seller in 1662 with The Day of Doom, but he followed this up in 1670 with a better seller, title Meat Out of the Eater. Maybe our reading hasn’t declined as much as we think.

By: Rebecca,

on 12/4/2008

Blog:

OUPblog

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

History,

words,

A-Featured,

Lexicography,

Dictionaries,

oed,

dictionary,

ammon shea,

expert,

Add a tag

Ammon Shea recently spent a year of his life reading the OED from start to finish. Over the next few months he will be posting weekly blogs about the insights, gems, and thoughts on language that came from this experience. His book, Reading the OED, has been published by Perigee, so go check it out in your local bookstore. In the post below Ammon wonders what makes an expert?

From time to time someone will find my email address and decide that they want to ask me a question. Usually this question is about obscure words or dictionaries, with an occasional query in some other almost inexplicable direction (I say ‘almost’ because my web site does say ‘email me with questions about obscure English words, or anything else that tickles your fancy’).

I don’t at all mind answering these questions, and usually find them interesting. “Where can I find a facsimile reprint of Johnson’s first dictionary?” “What’s the word for the smell of rain?” “What is a good prefix to read in the dictionary?” But I am confused when people write me questions because they think I am an expert in  some other matter.

some other matter.

The other day a radio broadcaster wrote me, as he had recently done a story on the word ‘handicapped’ and the advocacy group that believed this word was offensive (as they thought it came from ‘cap-in-hand’, referring to a begging cripple), and wanted to have this word removed from parking signs. He had gotten some small aspect wrong in the story of the etymology of handicap, and now he wanted an expert he could speak to about this.

I explained to him that I was not an expert, but I could probably find him one. He apparently thought that a real expert was unnecessary, and so a few minutes later I was speaking with him on the phone, and trying to explain how the advocacy group had fallen victim to a false etymology.

Except that I wasn’t really explaining anything – I was just sitting there reading copies of the OED and of Merriam-Webster’s 11th Collegiate, and telling him what I saw. Which was that the word handicap was first cited in the OED in the middle of the 17th century (I think I got the date a few years wrong), referring to a kind of sport; and that handicapped was not used to refer to physically or mentally impaired people until more than two hundred years later (1891, according to Merriam-Webster). And that there was no evidence to suggest that the origins of the term had anything to do with begging, cap in hand.

I also said something about how it wasn’t necessary for the advocacy group to be correct – they could have got the etymology completely wrong and still be offended. I mentioned some racial epithets that were commonly thought to be of an origin that turned out to be a folk etymology, and they still managed to offend plenty of people quite effectively. The entire episode took perhaps ten minutes, and I doubt that it will have very much of an effect on anyone’s life.

But what exactly is an expert? Is it someone like me, hemming and hawing over an open book, juggling attempts to not spill the morning coffee and find a word or phrase that sounds authoritative? Or am I an anomaly, and are most experts in fact buttressed by decades of learning and scholarship; careful people who would never answer a question by flipping open the nearest book and giving a mumbled recitation of what they see there. Or are experts some mix between these two? If that is the case then I suppose we need further experts to tell them apart.

By: Rebecca,

on 11/20/2008

Blog:

OUPblog

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

language,

A-Featured,

Lexicography,

Dictionaries,

oed,

dictionary,

ammon shea,

Reading The OED,

reference books,

Add a tag

Ammon Shea recently spent a year of his life reading the OED from start to finish. Over the next few months he will be posting weekly blogs about the insights, gems, and thoughts on language that came from this experience. His book, Reading the OED, has been published by Perigee, so go check it out in your local bookstore. In the post below Ammon reflects on his visit to talk to 5th and 6th graders.

Are we born with a natural fear of reference books or does it have to be taught to us? This was the question on my mind last week as I was visiting my old grammar school to talk to the 5th and 6th grade classes about dictionaries.

I don’t remember who taught me how to use a dictionary, or when it happened, or at what point I began to  feel apprehensive about this use. But I know that for many of the years between when I first learned to spell and when I realized that I’d been misinterpreting the usage label ‘colloquial’ in the dictionary that I had been plagued by feelings of uncertainty whenever I went to consult a reference work. I’ve been trying to come up with a workshop of sorts that will dispel this uncertainty make the dictionary enjoyable for children, and I hoped that talking with the 11 and 12 year olds would help me in this.

feel apprehensive about this use. But I know that for many of the years between when I first learned to spell and when I realized that I’d been misinterpreting the usage label ‘colloquial’ in the dictionary that I had been plagued by feelings of uncertainty whenever I went to consult a reference work. I’ve been trying to come up with a workshop of sorts that will dispel this uncertainty make the dictionary enjoyable for children, and I hoped that talking with the 11 and 12 year olds would help me in this.

The 5th and 6th graders were considerably more engaged, engaging, and educated that I had thought they would be. I suppose it is common for people who have not done much teaching to make mistakes in gauging the educational level of their subjects, but I still was fairly surprised. Especially when I was talking to the 6th graders about how the meanings of certain words shift over time, and asked if any of them know the word maverick. I knew that some of them would know what it meant, but was not prepared for the 11 year old in the back row who piped up with “Well…I know that today maverick means someone who doesn’t follow convention…but wasn’t it originally an eponymous 19th century word from a cattle rancher in the West who refused to brand his livestock?” Suddenly afraid that I was talking to an entire classroom of etymologists specializing in regionalisms I decided to change the subject and asked what their favorite words were.

It appears that this particular group of sixth graders had been eagerly waiting for someone to come by to ask them about their favorite words, as the next ten minutes were taken up with a cacophony on shouted examples: “Wicked!” “Fer-shizzle!!” “Erudite!!!”

Both classes were highly enthusiastic about discussing language, and needed only the slightest provocation from me (as when I asked ‘what’s a word?’) and they would leap into a classroom-wide shouted argument about meaning and context that resembled a scrum of either befuddled or drunk semanticists:

“A word is a thing.”

“A word is not a thing – a word is the title of a thing.”

“But…what about the word ‘the’…is that the title of a thing?”

“Of course ‘the’ is a title…’the’ title – duh.”

“What about word…is word a word?”

“Oh…my…God…you are such an idiot!”

“Yeah, but what does idiot mean?”

I have no way of knowing whether the children to whom I spoke are representative of their age, but it was certain that they have not yet had their irrepressible enjoyment of language scolded out of them, or a fear of dictionaries bred in. They would make up new words constantly (Socko – a taco made with old socks), ask questions that were unencumbered by embarrassment (‘Doesn’t the word dude also mean butt-hair?’), and had no qualms about being excited about the dictionary (as was evidenced by the 5th grade teacher having to yell at the entire class that they had to put away their dictionaries).

There may indeed be some small grain of truth to the definition of ‘dictionary’ that is provided by Ambrose Bierce in his Devil’s Dictionary (‘A malevolent literary device for cramping the growth of a language and making it hard and inelastic’), but if so, it would appear to not take effect for these students until high school at least.

By: Rebecca,

on 10/30/2008

Blog:

OUPblog

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

Oxford,

jesus,

A-Featured,

Lexicography,

Dictionaries,

oed,

dictionary,

ammon shea,

krebs,

Reading The OED,

know…jesus,

owns,

“hmmm…that’s,

“hmmm…what,

“jesus,

lingerie,

Add a tag

Ammon Shea  recently spent a year of his life reading the OED from start to finish. Over the next few months he will be posting weekly blogs about the insights, gems, and thoughts on language that came from this experience. His book, Reading the OED, has been published by Perigee, so go check it out in your local bookstore. In the post below Ammon reflects on his trip to Oxford.

recently spent a year of his life reading the OED from start to finish. Over the next few months he will be posting weekly blogs about the insights, gems, and thoughts on language that came from this experience. His book, Reading the OED, has been published by Perigee, so go check it out in your local bookstore. In the post below Ammon reflects on his trip to Oxford.

The tired old truism about Americans and the English being two people separated by a common language is something I’ve long been aware of, so when I visited Oxford the other week there were very few difficulties in navigating the differences in speech. What I did find confusing was the way that the Oxfordians talk about their colleges – and one college in particular.

I was having dinner with a group of OUP editors (from the UK) and publicists (from New York), and half-way through the meal the principal of one of the local colleges, one Lord Krebs, stopped by and joined us. He was soon engrossed in conversation with the editors at the other end of the table. I was eavesdropping in an unintentional sort of way, and growing increasingly confused.

I think my confusion began when I overheard the following snippet:

“Hmmm…that’s funny, I didn’t know Jesus was Welsh…”

“You didn’t know Jesus was Welsh?”

As I began listening more intently I suddenly was overcome with the fear that these witty and erudite members of Oxford University Press with whom I was so impressed were actually all adherents of some strange evangelical movement.

“One of my duties for Jesus is to look after the real estate, and do you know…Jesus owns a lot of real estate.”

“Jesus owns real estate?”

“Why yes…tons of it.”

“Well, I’d always known that Jesus was well-off, but not rich.”

“I’d have to say that Jesus is stinking rich.”

“Hmmm…what kind of properties are you talking about?”

“Mostly, Jesus owns a lot of farms in Wales, but all kinds of places really. Did you know that Jesus even owns a lingerie store?”

“Jesus owns a lingerie store!?!?”

At this point the participants in the conversation noticed that all the Americans had stopped talking, and were exhibiting the sort of polite yet strained interest that one reserves for things that are unavoidable and potentially quite discomfiting. It turns out that Lord Krebs is the principal of Jesus College of the University of Oxford (“renowned for being one of the friendliest colleges in Oxford” according to its web site), and the locals unsurprisingly refer to the institution by its first name.

I returned to my meal, secure and comforted by the twin bits of knowledge that Jesus (the historical figure) was not selling naughty underwear and that wherever I visit I will always find the local vernacular something that will delightfully confuse me.

ShareThis

By: Rebecca,

on 10/23/2008

Blog:

OUPblog

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

ammon shea,

bicycles,

bars,

OED is 80,

cyclists,

similarities,

velocipedists,

claims”,

hague,

Oxford,

cars,

words,

A-Featured,

Lexicography,

Dictionaries,

oed,

dictionary,

Add a tag

Ammon Shea  recently spent a year of his life reading the OED from start to finish. Over the next few months he will be posting weekly blogs about the insights, gems, and thoughts on language that came from this experience. His book, Reading the OED, has been published by Perigee, so go check it out in your local bookstore. In the post below Ammon reflects on his trip to Oxford.

recently spent a year of his life reading the OED from start to finish. Over the next few months he will be posting weekly blogs about the insights, gems, and thoughts on language that came from this experience. His book, Reading the OED, has been published by Perigee, so go check it out in your local bookstore. In the post below Ammon reflects on his trip to Oxford.

I always find it bemusing to travel to a new place, and the things I find most striking are not the overt and major differences between where I’m traveling and where I’m from. I tend to focus on the things that remind me of home, but which are slightly different – and somehow the similarities make it all feel even more foreign, as though I’ve stepped into an altered version of where I’m from.

Oxford is a city full of bicycles and old bars. We have cyclists and bars in New York City, but not in the same way. When exiting the train station in Oxford the first thing I noticed was not the splendid old buildings, or the difference in light, or the cars driving on the other side of the road; the first thing I noticed was the sea of hundreds and hundreds of bicycles parked in a lot next to the street. The only time I’ve ever seen such a profusion of bicycles here was last year, when I saw some news footage of a man in a nearby town who had been stealing bicycles for years, and had managed to accumulate a similar number.

The cyclists in Oxford seem to have much of the casual disregard for safety as do those of my hometown, weaving in and about the cars and pedestrians. But they also signal when they are planning on turning, giving a curious chopping motion of the arm. This never happens in New York, and it took me a day or two before I realized that this arm chop presaged a turn, and was not a widespread neurological disorder that afflicted English velocipedists.

And while there is no shortage of bars in New York, I found it almost unnerving to walk into a drinking establishment that was established several hundred years before the government of the country that I come from. The students lounging about on a Saturday evening looked not so different from those of New York, but the fact that the wall that they were boozily leaning against had held up inebriated youth for five hundred years made it feel markedly askew.

It’s the differences within the similarities that make Oxford feel like such a foreign place to me. Although I should confess that there were occasions this foreign-ness was also made obvious by something which bore absolutely no similarity to what I am used to in America. Such as when I picked up the paper one morning and saw that William Hague had attacked Gordon Brown for what he termed his “hubristic and irresponsible claims”. I am trying to remember the last time I heard a national politician here use a word such as “hubristic” without fear of being tarred with the elitist brush, and I cannot think of when that might be. This is a depressing thought, and I suppose that is why I spend my travels looking at bicycles and bars.

ShareThis

By: Kirsty,

on 10/15/2008

Blog:

OUPblog

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

john simpson,

History,

Reference,

UK,

Current Events,

A-Featured,

Lexicography,

Dictionaries,

Online Resources,

oed,

oxford english dictionary,

ammon shea,

Samuel Johnson,

simon winchester,

Add a tag

By Kirsty McHugh, OUP UK

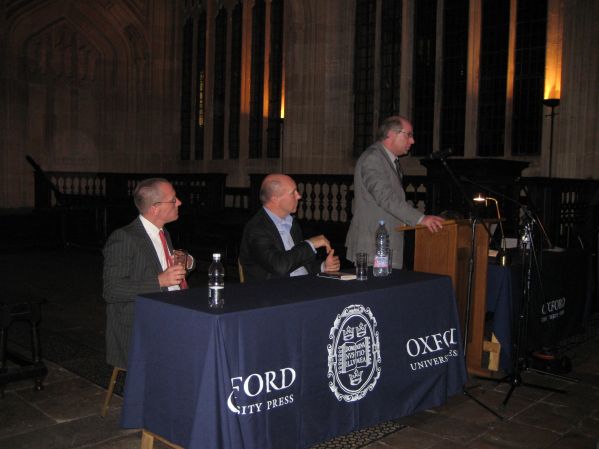

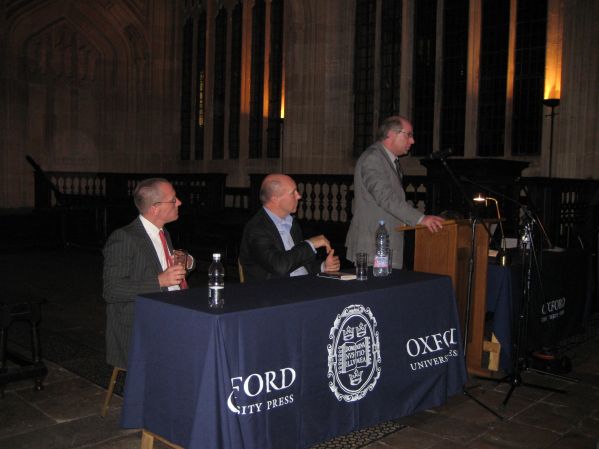

Last night saw the OED 80th Anniversary celebrations culminate in a public panel discussion on  ‘The Oxford English Dictionary: Past, Present, and Future’ at the incredibly beautiful and historic Bodleian Library in Oxford.

‘The Oxford English Dictionary: Past, Present, and Future’ at the incredibly beautiful and historic Bodleian Library in Oxford.

On the panel was OED chief editor John Simpson, historian and author of The Meaning of Everything: The Story of the Oxford English Dictionary Simon Winchester, and Ammon Shea, who wrote Reading the OED and who of course needs no introduction to OUPblog readers.

Simon Winchester opened up proceedings with a history of dictionaries, telling us that 1604 saw the first modern  dictionary as we understand them today. In that case, it was a slim book written by Robert Cawdrey called A table alphabeticall conteyning and teaching the true writing, and vnderstanding of hard vsuall English wordes, borrowed from the Hebrew, Greeke, Latine, or French, &c. With the interpretation thereof by plaine English words, gathered for the benefit & helpe of ladies, gentlewomen, or any other vnskilfull persons. Whereby they may the more easilie and better vnderstand many hard English wordes, vvhich they shall heare or read in scriptures, sermons, or elswhere, and also be made able to vse the same aptly themselues. Snappy, huh?

dictionary as we understand them today. In that case, it was a slim book written by Robert Cawdrey called A table alphabeticall conteyning and teaching the true writing, and vnderstanding of hard vsuall English wordes, borrowed from the Hebrew, Greeke, Latine, or French, &c. With the interpretation thereof by plaine English words, gathered for the benefit & helpe of ladies, gentlewomen, or any other vnskilfull persons. Whereby they may the more easilie and better vnderstand many hard English wordes, vvhich they shall heare or read in scriptures, sermons, or elswhere, and also be made able to vse the same aptly themselues. Snappy, huh?

He then went on to talk about arguably the most famous dictionary (other than the OED obviously!): that by Samuel Johnson. Johnson was known as a bit of a cantankerous fellow, and this sometimes filtered down into his definitions. For example, his famous definition of ‘oats’:

A grain, which in England is generally given to horses, but in Scotland appears to support the people.

I won’t take offence, promise. Then we heard about the famous OED editors of the late 19th and early 20th century: Herbert Coleridge, Frederick Furnivall (who had to leave the job after it was realised that he was more interested in sculling and well-endowed young ladies), and, of course, James Murray.

John Simpson, today’s OED editor, took us through what happens to an entry and the kinds of information that is needed for the Dictionary. He used the example of ‘lifeboat’ and took us through its history from its first appearance in the first edition of the OED , to moving from being hyphenated (life-boat) to a solid word in 1903, up to the latest evidence of its earliest usage, which will be in the updated entry to go online soon.

Then, to finish the evening, Ammon Shea told us all about reading the OED from A-Z in one year. To read more about the many wonderful words he discovered during that year, then do read his past posts for OUPblog. But I couldn’t agree with him more when he said that there is much emotional content within the Oxford English Dictionary: the poignancy of a word that means ‘to no longer own something, but to wish that you still did’, or a word that means ‘the sound of leaves rustling in the wind’. The OED is, as Ammon said, a “remarkable creature of literature”, which is why I am so happy to have been here for the 80th anniversary celebrations.

Here’s to another 80 years, and many, many more.

ShareThis

By: Rebecca,

on 9/18/2008

Blog:

OUPblog

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

oed,

dictionary,

ammon shea,

carly,

clarify,

defecate,

clarifying,

clarified,

fiorina,

impurities,

conspiratorially,

Politics,

A-Featured,

Lexicography,

Dictionaries,

Add a tag

Ammon Shea  recently spent a year of his life reading the OED from start to finish. Over the next few months he will be posting weekly blogs about the insights, gems, and thoughts on language that came from this experience. His book, Reading the OED, has been published by Perigee, so go check it out in your local bookstore. In the post below Ammon looks at the frequent use of the word “clarify”.

recently spent a year of his life reading the OED from start to finish. Over the next few months he will be posting weekly blogs about the insights, gems, and thoughts on language that came from this experience. His book, Reading the OED, has been published by Perigee, so go check it out in your local bookstore. In the post below Ammon looks at the frequent use of the word “clarify”.

All of a sudden there appears to be a whole lot of clarifying going on. The New York Times wrote an editorial yesterday that said of John McCain “On Tuesday, he clarified his remarks” regarding the economy. And the Christian Science Monitor recently wrote an article about a slip of the tongue committed by one of McCain’s advisors, Carly Fiorina, in which she said some inopportune things about who could and couldn’t run her company into the ground as well as she had (“In the next interview she clarified the first remark by stating John McCain couldn’t run a major company either.”).

According to the Scotsman, aides to Sarah Palin “have clarified that a purported visit to Ireland was little more than a refuelling stop at Shannon during her trip to the Middle East.” And a recent article in the Las Vegas Sun tells us that Barack Obama has clarified the comment he’d made to a group in Iowa, “Nobody is suffering more than the Palestinian people.”

If the meaning of a word were entirely defined by how it was used one might be excused for looking through the news of late and thinking that clarify means “To equivocate esp. for political ends; to attempt to change a statement after realizing that it has not has the desired effect.”

I sometimes fall prey to a sneaking suspicion that the rest of the word has got together and had a huddle, in which they’ve all whispered conspiratorially to one another, and have decided that certain words that used to mean one thing will now mean something else entirely, and I am the only one who does not know about this. And the more often I see clarify meaning “Please forget that silly thing I said before and pay attention to this new shiny thing I am saying now” the more I wonder what other words have changed meaning since Monday.

But maybe there’s something else - maybe there is some meaning of clarify of which I am unaware. Perhaps all the politicians and the writers from these newspapers have all just been waxing poetic, or quoting the Tyndale Bible, and it’s been going right over my head. So I turned to the OED and was delighted when I found that the last bit of definition 3B of clarify utterly confirmed these suspicions – “to defecate or fine. Also fig.”

Finally the tail-end of a definition 3B turns out to be terribly important – when these politicians are clarifying they are in fact defecating (in a figurative sense, of course). I was so relieved that things seemed to make more sense that I almost forgot to check the definition of defecate, just in case it too meant some thing other than what I’d thought.

However, I did check on defecate, and of course the first meaning of this word that I thought I knew is “To clear from dregs or impurities; to purify, clarify, refine.” I have now stopped trying to figure out what this word means - but I have decided that if I ever have the need to write a dictionary I’m going to hire a bunch of political operatives to clarify all my definitions when I’m done.

ShareThis

By: Rebecca,

on 9/11/2008

Blog:

OUPblog

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

uppity,

Westmoreland,

caucasian,

racist,

nuance,

“just,

racially,

Politics,

A-Featured,

Lexicography,

Dictionaries,

meaning,

usage,

oed,

dictionary,

Obama,

ammon shea,

senator,

Add a tag

Ammon Shea  recently spent a year of his life reading the OED from start to finish. Over the next few months he will be posting weekly blogs about the insights, gems, and thoughts on language that came from this experience. His book, Reading the OED, has been published by Perigee, so go check it out in your local bookstore. In the post below Ammon looks at the word “uppity”.

recently spent a year of his life reading the OED from start to finish. Over the next few months he will be posting weekly blogs about the insights, gems, and thoughts on language that came from this experience. His book, Reading the OED, has been published by Perigee, so go check it out in your local bookstore. In the post below Ammon looks at the word “uppity”.

Last week a member of the House of Representatives, Lynn Westmoreland of Georgia, created a stir when he used the word uppity in conjunction with Michelle and Barack Obama. As reported in The Hill, a Capitol Hill newspaper, Westmoreland said “Just from what little I’ve seen of her and Mr. Obama, Sen. Obama, they’re a member of an elitist-class individual that thinks they’re uppity.”

The remark has drawn wide-spread coverage, and no small amount of condemnation from people who are of the opinion that uppity is what has been delicately termed ‘a racially-tinged’ word. Westmoreland himself has staked out the rather bold position that it is possible to have lived in the South for some five decades and not be aware of the potentially offensive meaning of this word, and offers his own ostensible ignorance as proof of this.

The question of whether the Representative from Georgia is or is not lying has been written about in many other places, as has the question of what would be the appropriate response from the Senator from Illinois or his wife; so have all the other questions of propriety of social discourse, and I’ll not mention them further. What I find interesting is just how difficult it is to really capture the nuance and breadth of a word such as uppity in the dictionary.

It appears to be widely acknowledged that the word has connotations of racism, at least as it was applied to the Obamas. Indeed, much of the commentary has focused on the fact that it would be surprising (or hard to believe) that Westmoreland did not know that he was using a racist turn of phrase. And yet a brief check of several contemporary general dictionaries (the OED, Merriam-Webster, the Encarta) and we find that none of them include this information in their definitions, or in a usage note.