new posts in all blogs

Viewing: Blog Posts Tagged with: Lexicography, Most Recent at Top [Help]

Results 1 - 25 of 260

How to use this Page

You are viewing the most recent posts tagged with the words: Lexicography in the JacketFlap blog reader. What is a tag? Think of a tag as a keyword or category label. Tags can both help you find posts on JacketFlap.com as well as provide an easy way for you to "remember" and classify posts for later recall. Try adding a tag yourself by clicking "Add a tag" below a post's header. Scroll down through the list of Recent Posts in the left column and click on a post title that sounds interesting. You can view all posts from a specific blog by clicking the Blog name in the right column, or you can click a 'More Posts from this Blog' link in any individual post.

By: Lauren,

on 11/23/2010

Blog:

OUPblog

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

Editor's Picks,

*Featured,

allan metcalf,

american dialect society,

metcalf,

Lexicography,

okay,

little women,

ok,

word history,

andrew jackson,

etmology,

Add a tag

Some books are amazing, and some are not, and some are OK. (Yes, I can make bad jokes like this all day, and I shall.) Below is a Q&A with author Allan Metcalf about his book OK: The Improbable Story of America’s Greatest Word. Metcalf is also Professor of English at MacMurray College, Executive Secretary of the American Dialect Society, and punnier than I can ever hope to be. -Lauren Appelwick, Blog Editor

Q. Why write a whole book about OK? I mean, it’s just…OK.

A. Ah, but it’s OK the Great: the most successful and influential word ever invented in America. It’s our most important export to languages around the world—best known and most used, though used sometimes in weird ways. It expresses the pragmatic American outlook on life, the American philosophy if you will, in two letters. And in the twenty-first century, inspired by the 1967 book title I’m OK, You’re OK (which is the only famous quotation involving OK), it also has taught us to be tolerant of those who are different from us. On top of all that, its origin almost defies belief (it was a joke misspelling of “all correct”) and its survival after that inauspicious origin was miraculous. And strangely, though we use it all the time, we carefully avoid it when we’re making important documents and speeches. So, wouldn’t you say OK deserves a book?

Q. Then why hasn’t someone written an “OK” book before?

A. Good question. The answer goes back to your first question—it’s just OK. It’s so ordinary, so common nowadays that we use it without thinking. And its meaning is lacking in passion, so it doesn’t seem very interesting. But that’s just what is interesting. OK is a unique way to indicate approval without having to approve. If we want to express enthusiasm when using OK, we have to add something, like an A or an exclamation mark, AOK or OK! The neutrality of OK is incredibly useful, but it doesn’t catch our attention, and so there has been no previous book. Mine is a wake-up call, I hope.

Now although there haven’t been books, there have been articles aplenty about OK. But they mostly deal with the origins of OK, and they are mostly wrong. The true beginning of OK is truly improbable.

Q. OK, so why are so many explanations wrong? And what is the true origin?

A. Very soon after the birth of OK, its origins were deliberately misidentified, and for more than a century etymologists were led astray by that red herring. It was only in the 1960s that a scholar of American English, Allen Walker Read, did the research and published the detailed evidence that shows beyond a doubt—

Q. What?

A. That OK began as a joke in the Boston Morning Post of Saturday, March 23, 1839. As Read demonstrated, the Post’s o.k., which was explained to mystified readers as an abbreviation for “all correct,” was just one of numerous joking abbreviations employed by Boston newspaper editors to enliven their stories, two others being “o.f.m.” for “our first men” and “o.w.” for “all right.”

Q. So how come nobody remembered that explanation?

A. Because other explanations sprang up before OK was a year old.

One explanation was true, as far as it goes. Martin Van Buren was running for reelection as the Democratic candidate for president of the United States. Well, it happens that his hometown was Kinderhook, New York, so in the election year 1840 his supporters began to call

By: Lauren,

on 11/22/2010

Blog:

OUPblog

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

Dennis Baron,

A Better Pencil,

refudiate,

Editor's Picks,

*Featured,

grammar nazi,

grammar police,

grammar,

Lexicography,

Dictionaries,

english,

twitter,

tweet,

Sarah Palin,

Add a tag

By Dennis Baron

Last Spring the New York Times reported that more and more grammar vigilantes are showing up on Twitter to police the typos and grammar mistakes that they find on users’ tweets. According to the Times, the tweet police “see themselves as the guardians of an emerging behavior code: Twetiquette,” and some of them go so far as to write algorithms that seek out tweets gone wrong (John Metcalfe, “The Self-Appointed Twitter Scolds,” April 28, 2010).

Last Spring the New York Times reported that more and more grammar vigilantes are showing up on Twitter to police the typos and grammar mistakes that they find on users’ tweets. According to the Times, the tweet police “see themselves as the guardians of an emerging behavior code: Twetiquette,” and some of them go so far as to write algorithms that seek out tweets gone wrong (John Metcalfe, “The Self-Appointed Twitter Scolds,” April 28, 2010).

Twitter users post “tweets,” short messages no longer than 140 characters (spaces included). That length restriction can lead to beautifully-crafted, allusive, high-compression tweets where every word counts, a sort of digital haiku. But most tweets are not art. Instead, most users use Twitter to tell friends what they’re up to, send notes, and make offhand comments, so they squeeze as much text as possible into that limited space by resorting to abbreviations, acronyms, symbols, and numbers for letters, the kind of shorthand also found, and often criticized, in texting on a mobile phone.

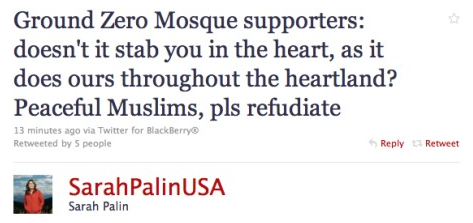

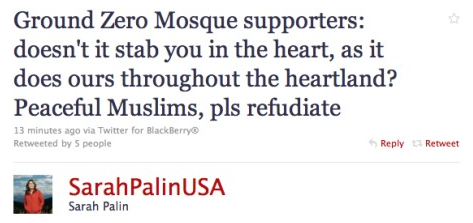

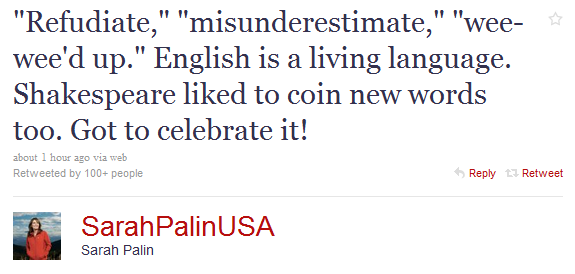

But what the tweet police are looking for are more traditional usage gaffes, like problems with subject-verb agreement, misspellings, or incorrect use of apostrophes. And they don’t like mistakes in word choice, as when Sarah Palin tweeted refudiate, not repudiate, in her objection to the Islamic Cultural Center being built near Ground Zero in lower Manhattan.

Palin is one of the celebrities on Twitter whose posts get a lot of scrutiny from the grammar watchers. But while refudiate was perceived to be an error, it’s not exactly a new word. According to Ammon Shea, it first appeared in 1891, and Ben Zimmer finds it surfacing again in 1925.

The immediate clamor that followed Palin’s use of refudiate in her July 18, 2010, tweet led Palin or someone on her staff to replace the original tweet with the edited version below. However, switching refudiate to refute didn’t placate the language purists, who insisted that she should have said repudiate.

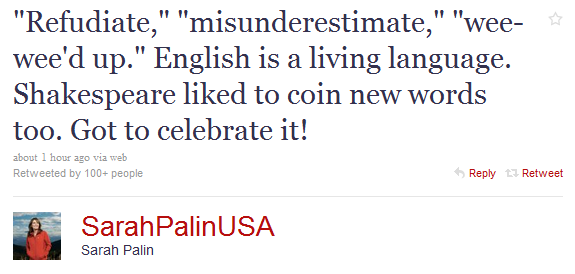

In a tweet later that same day (below), Palin decided to recast her mistake as an experiment in creativity, arguing that word coinage is common in English and suggesting that her use of refudiate was somehow Shakespearean.

As if to prove her point, the editors of the

0 Comments on ” :) when you say that, pardner” – the tweet police are watching as of 1/1/1900

By Anatoly Liberman

Last week I wrote that one day I would reproduce some memorable statements from Skeat’s letters to the editors. This day has arrived. I have several cartons full of paper clippings, the fruit of the loom that has been whirring incessantly for more than twenty years: hundreds of short and long articles about lexicographers, with Skeat occupying a place of honor. A self-educated man in everything that concerned the history of Germanic, he became the greatest expert in Old and Middle English and an incomparable etymologist. In England, only Murray, the editor of the OED, and Henry Sweet were his equals, and in Germany, only Eduard Sievers. Joseph Wright, another autodidact, the editor of the English Dialect Dictionary, was interested in many things outside English philology, but for Skeat English remained the prime object of research all his life. Like most people who learned so much the hard way (that is, on their own), he despised ignorance, especially when it hid behind pretense and pomposity. A professor (though not burdened with too much teaching, especially by modern standards) and a family man (yet in this area he could not compete with Murray, the father of a whole brood of children), he never flinched at the idea of writing an edifying or indignant letter to the editor, for he was a born enlightener. He chose as his perennial target was the inability of his countrymen to understand that etymology is a science rather than mildly intelligent guesswork.

James Murray often asked the readers of popular journals (especially of Notes and Queries) to send him information on the words he was editing, and his letters used to end with one and the same refrain: “But please send me facts, not guesses.” Skeat offered a short “treatise” on this subject:

“As to ‘guesses’, they differ greatly. It is quite one thing for a person to make them without any investigation and in defiance of all known phonetic and philological laws; and quite another thing to offer a suggestion for which it is worth after all available means of obtaining information have been exhausted. It is a curious thing that the worse a guess is the more obstinately it is maintained, the object being to hide ignorance by raising a cloud of dust…. The whole matter lies in a nutshell. If a man is entirely ignorant of botany or chemistry, he leaves those subjects alone. But if a man is entirely ignorant of the principles of philology (which has lately [1877] made enormous advances), he does not leave the subject alone, but considers his ‘opinions’ as good as the most assured results of the most competent scholars. The knowledge of a language is often supposed to carry with it the knowledge of the laws of formation of the language. But this is not in the least the case…. My object has always been the same, viz., to protest against the usual state of things. In course of time the lesson will be learnt that there is really no glory to be got by making elementary blunders, or by suggesting ridiculous emendations even of Shakespeare. I cannot at all acquiesce in the notion that people who talk nonsense must never be reproved for it.”

As an illustration of the principle that there is no glory to be got by making elementary blunders, I will quote Skeat’s pronouncement on the word bower and on his opponent, a certain A.H.: “I submit that Old English should be learnt, like any other subject, by honest hard work, and the sense of old words ought not to be evolved from one’s internal consciousness…. A.H. is merely showing us how little he has really studied the subject….” The abrasive tone of Skeat’s letters made many people wince: after all, no one likes bein

By: Lauren,

on 11/16/2010

Blog:

OUPblog

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

podcast,

Lexicography,

Dictionaries,

itunes,

Sarah Palin,

Word of the Year,

New Oxford American Dictionary,

noad,

refudiate,

christine,

The Oxford Comment,

oxford comment,

lexicographer,

*Featured,

quickcast,

lindberg,

Add a tag

If you haven’t heard – well, how haven’t you heard? “Refudiate” is the New Oxford American Dictionary’s 2010 Word of the Year. (And no, that doesn’t mean “refudiate” has been added to the NOAD or any other Oxford dictionary.) In this quickcast, Michelle and Lauren talk with NOAD Senior Lexicographer Christine Lindberg, and take to the streets to see what people think of this special word – or shall we say word blend?

Subscribe and review this podcast on iTunes!

Music by The Ben Daniels Band.

By: Lauren,

on 11/15/2010

Blog:

OUPblog

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

Reference,

Lexicography,

Dictionaries,

twitter,

Sarah Palin,

glee,

webisode,

Word of the Year,

crowdsourcing,

New Oxford American Dictionary,

retweet,

tea-party,

vuvuzela,

refudiate,

Editor's Picks,

*Featured,

bankster,

double-dip,

gleek,

nom,

top kill,

Add a tag

Editor’s note: I love being right. I really, really love it. In July, I guessed that “refudiate” would be named Word of the Year, and TA-DAH! I was right. What Paul the Octopus was to the FIFA World Cup, I am to WOTY (may he rest in peace). But that’s enough about me because what’s really important is that…

Refudiate

has been named the New Oxford American Dictionary’s 2010 Word of the Year!

refudiate verb used loosely to mean “reject”: she called on them to refudiate the proposal to build a mosque.

[origin — blend of refute and repudiate]

Now, does that mean that “refudiate” has been added to the New Oxford American Dictionary? No it does not. Currently, there are no definite plans to include “refudiate” in the NOAD, the OED, or any of our other dictionaries. If you are interested in the most recent additions to the NOAD, you can read about them here. We have many dictionary programs, and each team of lexicographers carefully tracks the evolution of the English language. If a word becomes common enough (as did last year’s WOTY, unfriend), they will consider adding it to one (or several) of the dictionaries we publish. As for “refudiate,” well, I’m not yet sure that it will be includiated.

Refudiate: A Historical Perspective

An unquestionable buzzword in 2010, the word refudiate instantly evokes the name of Sarah Palin, who tweeted her way into a flurry of media activity when she used the word in certain statements posted on Twitter. Critics pounced on Palin, lampooning what they saw as nonsensical vocabulary and speculating on whether she meant “refute” or “repudiate.”

From a strictly lexical interpretation of the different contexts in which Palin has used “refudiate,” we have concluded that neither “refute” nor “repudiate” seems consistently precise, and that “refudiate” more or less stands on its own, suggesting a general sense of “reject.”

Although Palin is likely to be forever branded with the coinage of “refudiate,” she is by no means the first person to speak or write it—just as Warren G. Harding was not the first to use the word normalcy when he ran his 1920 presidential campaign under the slogan “A return to normalcy.” But Harding was a political celebrity, as Palin is now, and his critics spared no ridicule for his supposedly ignorant mangling of the correct word “normality.”

The Short List

In alphabetical order, here are our top ten finalists for the 2010 Word of the Year selection:

By: Lauren,

on 11/10/2010

Blog:

OUPblog

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

digitalis,

Oxford Etymologist,

Lexicography,

word origins,

english,

anatoly liberman,

etymologies,

foxglove,

*Featured,

plant names,

Add a tag

By Anatoly Liberman

The origin of plant names is one of the most interesting areas of etymology. I have dealt with henbane, hemlock, horehound, and mistletoe and know how thorny the gentlest flowers may be for a language historian. It is certain that horehound has nothing to do with hounds, and I hope to have shown that henbane did not get its name because it is particularly dangerous to hens (which hardly ever peck at it, and even if they did, why should they have been chosen as the poisonous plant’s preferred victims?). On the face of it, the word foxglove makes no sense, because foxes do without gloves and even without hands. The scientific name of foxglove is Digitalis (the best-known variety is Digitalis purpurea), apparently, because it looks like a thimble and can be easily fitted over a finger (Latin digitus “finger”). See more about it below. The puzzling part is fox-. It was such even in Old English (foxes glofa, though the name seems to have been applied to a different plant), so that nothing has been “corrupted,” to use one of the favorite words of 19th-century etymologists, both professional and amateurs.

It is amusing what fierce battles have been fought over the origin of the word foxglove. Walter W. Skeat broke many a spear defending the simplest etymology (foxglove is fox + glove), but neither he nor anyone else has been able to explain how the Anglo-Saxons came by this name: why fox? Regardless of the solution, reading Skeat is always a pleasure, and I will probably devote a post to a selection of quotes from his letters to the editor. With regard to foxglove, he remarked: “…everyone writes on etymology, more especially such as do not understand it.” How true, how very true! Among other things, Skeat produced an impressive list of Old English plant names with obscure references to animals in them, for example, fowl’s bean, cow-slip (not cow’s lip!), ox-heal, catmint, and hound’s fennel. And we know dog rose and wolfsbane, to mention just a few oddities. Each of them needs an explanation, and I think Skeat pooh-poohed the question too hastily. He wrote: “… [to us] such names as fox-glove and hare-bell seem senseless, and many efforts, more ingenious than well directed, have been made to evade the evidence. Yet, it is easily understood. The names are simply childish, and such as children would be pleased with. A child only wants a pretty name, and is glad to connect a plant with a more or less familiar animal. This explains the whole matter, and it is the reverse of scientific to deny a fact merely because we dislike or contemn [sic] it. This is not the way to understand the workings of the human mind, on which true etymology often throws much unexpected light.” Unfortunately, the Anglo-Saxons were not children, and though, like us, they certainly enjoyed playing with language and inventing “pretty names,” those names cannot be written off as silly or irrational. So let me repeat: foxglove does go back to a word that means exactly this (fox-glove), and all attempts to explain it as a “perversion” of some other compound or phrase are misguided, but the reason for endowing the flower with such an incomprehensible name has not been discovered.

The idea to trace foxglove to folk’s (or folks’) glove is relatively recent. It may have gained popularity after the publication of the book English Etymologies by William Henry Fox (!) Talbot (1847). We read the following in it: “In Welsh this flower is called by the beauti

By: Lauren,

on 11/9/2010

Blog:

OUPblog

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

India,

Lexicography,

Featured,

english,

learn english,

Eastern Religion,

hindu,

Dennis Baron,

goddess of english,

national language,

official language,

macaulay,

Current Events,

Add a tag

By Dennis Baron

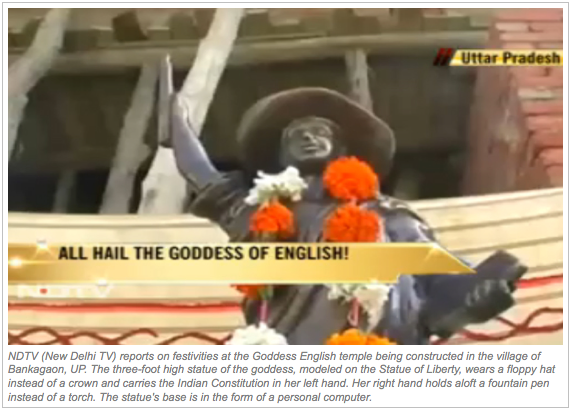

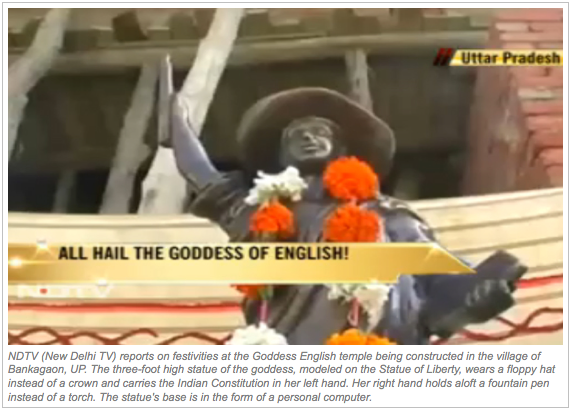

Global English may be about to go celestial. A political activist in India wants the country’s poorest caste to improve its status by worshipping the English language, and to start off he’s building a temple to Goddess English in the obscure village of Bankagaon, near Lakhimpur Khiri in Uttar Pradesh.

Global English may be about to go celestial. A political activist in India wants the country’s poorest caste to improve its status by worshipping the English language, and to start off he’s building a temple to Goddess English in the obscure village of Bankagaon, near Lakhimpur Khiri in Uttar Pradesh.

English started on the long path to deification back in the colonial age, and in many former British colonies English has become both an indispensable tool for survival in the modern world and a bitter reminder of the Raj. In 1835, Thomas Babington Macaulay recommended to fellow members of the India Council that the British create a system of English-language schools in the colony to train an elite class of civil servants, “Indian in blood and colour, but English in tastes, in opinions, in morals and in intellect,” who would help the British rule the subcontinent.

The philologist William Jones, who visited India almost 50 years before Macaulay, had a much more positive view of Indian language and culture. “Oriental” Jones, as he was sometimes called, praised Sanskrit as “more perfect than the Greek, more copious than the Latin, and more exquisitely refined than either,” and he demonstrated that Sanskrit, Latin, and Greek all shared a common Indo-European ancestor. But Macaulay didn’t think much of India’s ancient linguistic heritage, and he told the Council, “A single shelf of a good European library [is] worth the whole native literature of India and Arabia.” Macaulay argued that British support for India’s traditional Arabic and Sanskrit schools gave “artificial encouragement to absurd history, absurd metaphysics, absurd physics, absurd theology.” In their place he recommended English-language schools that would civilize India, as European languages had already civilized Russia: “I cannot doubt that they will do for the Hindoo what they have done for the Tartar.”

Today Indian nationalists shun Macaulay for his condescending, Eurocentric view of language and culture, but the Dalit activist Chandra Bhan Prasad wants millions of India’s Dalits (the former untouchable caste, before caste discrimination was outlawed), to learn English and let their local languages “wither away.”

Prasad celebrates Macaulay’s birthday, Oct. 25, as “English Day.” But to make English more attractive to ordinary Dalits, he’s created Goddess English, whose image is modeled on the Statue of Liberty, though the goddess wears a floppy hat instead of a crown, carries a copy of the Indian Constitution (the days of the Raj being long gone), and holds aloft a fountain pen. Prasad argues that “Universalism [is] central to the soul of Goddess English,” while India’s indigenous languages are both divisive and discriminatory. For him, speaking English is the way for Dalits to exchange their hereditary poverty for high-status jobs in science and IT, which is why his statue of Goddess English stands on a personal computer.

-

0 Comments on All hail goddess English? as of 1/1/1900

By: Lauren,

on 11/3/2010

Blog:

OUPblog

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

Featured,

word origins,

oed,

anatoly liberman,

codger,

word histories,

cadger,

old codger,

codge,

Oxford Etymologist,

Lexicography,

Add a tag

A Whimsical Etymology of a Whimsical Word

By Anatoly Liberman

Old codger is a phrase most speakers of American English still understand (in British English it has much greater currency), but

cadger is either obsolete or dead. Yet the two words are often discussed in concert. A cadger was a traveling vendor, whose duties may have differed from that of a hawker, a peddler (the British spelling is

pedlar), or a badger, but all those people were street dealers of sorts. The

OED defines

cadger so: “a carrier;

esp. a species of itinerant dealer who travels with a horse and cart (or formerly with a pack-horse), collecting butter, eggs, poultry, etc., from remote country farms for disposal in the town, and at the same time supplying the rural districts with small wares from the shops.” This meaning was recorded as early as the middle of the 15

th century. Derogatory senses like “a person prone to mooching” surfaced in books much later. Also late is the verb

cadge “beg,” believed to be a back formation from the noun (like

beg from

beggar). The origin of

cadger is unknown, and I have nothing to say on this subject, except for guessing that it must have been influenced by

badger and citing a very old opinion, according to which in the days of falconry the man who bore the “cadge” or cage (a perch for the hawk) was called

cadger. This etymology has little to recommend it.

The word that inspired the present post is codger “stingy (old) man,” “grumpy elderly man,” or simply “man” (like chap, fellow, or guy). It appeared in books only at the very end of the 18th century, and dictionaries say that it may be a dialectal variant of cadger. This is possible, but, to my mind, unlikely. Other etymologies are not even worth considering: from Engl. cottager, Engl. cogitate, German kotzen “to vomit,” Spanish, Turkish, Irish Gaelic, or (particularly silly) from the phrase coffee dodger. I am surprised no one derived codger from kosher. On January 18, 1890, Notes and Queries published the following letter by the OED’s editor James A.H. Murray, who was at that time working on the letter C: “Todd explains this [the word codger] as ‘contemptuously used for a miser, one who rakes together all he can’, in accordance with his own conjectural derivation from Sp[anish] coger, ‘to gather, get as he can’. Later dictionaries all take this sense from him (Webster with wise expression of doubt), but none of them gave any evidence. I have not heard it so used, nor does any suspicion of such a sense appear in any of the thirty quotations sent in for the word by our readers. Has Todd’s explanation any basis? A schoolboy to whom I have spoken seems to have heard it so used; but he may have confused it with cadger, which many take as the same.” Todd was the editor of Samuel Johnson’s dictionary (1818).

Several people responded to Murray’s query. The luckless schoolboy was derided for his incompetence, and almost everybody insisted that codger, unlike cadger, is a term of endearment, but one letter writer pointed out that in the fifties of the 19th century in Derbyshire (the East Midlands) “codger or rummy codger had been constantly used when alluding to persons of peculiar and eccentric ways, as well of others of doubtful character, or of whom mistrust was felt. A bungler of work was termed a codger, and it was the fate of every little lass who did sewing at school to cadge her work, that is, make an unsightly mess of the stitching. A piece of bad sewing

By: Lauren,

on 10/29/2010

Blog:

OUPblog

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

language,

Lexicography,

Featured,

pet peeve,

LOL,

phrases,

Dennis Baron,

A Better Pencil,

colloqualisms,

literally,

Add a tag

By Dennis Baron

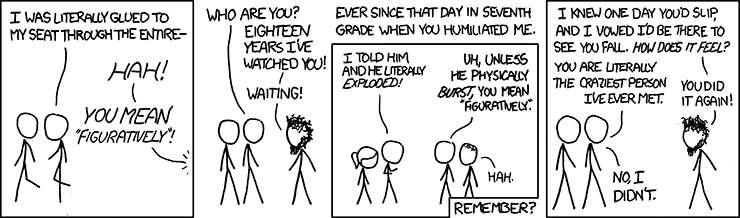

The English language is full of paradoxes, like the fact that “literally” pretty much always means ‘figuratively.’ Other words mean their opposites as well–”scan” means both ‘read closely’ and ’skim.’ “Restive” originally meant ’standing still’ but now it often means ‘antsy.’ “Dust” can mean ‘to sprinkle with dust’ and ‘to remove the dust from something.’ “Oversight” means both looking closely at something and ignoring it. “Sanction” sometimes means ‘forbid,’ sometimes, ‘allow.’ And then there’s “ravel,” which means ‘ravel, or tangle’ as well as its opposite, ‘unravel,’ as when Macbeth evokes “Sleepe that knits up the rauel’d Sleeue of Care.”

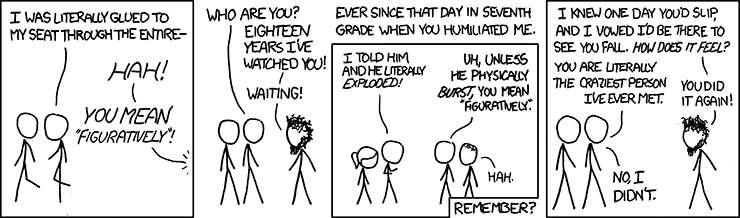

No one objects to these paradoxes. But if you say “I literally jumped out of my skin,” critics will jump on your lack of literacy. Their insistence that literally can only mean, well, ‘literally,’ ignores the fact that word has meant ‘figuratively’ for centuries.

If you’re tempted to correct someone’s figurative use of literally, remember, nobody likes a smartass. (courtesy of XKCD)

The English language is full of paradoxes, like the fact that “literally” pretty much always means “figuratively. Other words mean their opposites as well–”scan” means both ‘read closely’ and ’skim.’ “Restive” originally meant ’standing still’ but now it often means ‘antsy.’ “Dust” can mean ‘to sprinkle with dust’ and ‘to remove the dust from something.’ “Oversight” means both looking closely at something and ignoring it. “Sanction” sometimes means ‘forbid,’ sometimes, ‘allow.’ And then there’s “ravel,” which means ‘ravel, or tangle’ as well as its opposite, ‘unravel,’ as when Macbeth evokes “Sleepe that knits up the rauel’d Sleeue of Care.”

No one objects to these paradoxes. But if you say “I literally jumped out of my skin,” critics will jump on your lack of literacy. Their insistence that literally can only mean, well, ‘literally,’ ignores the fact that word has meant ‘figuratively’ for centuries.

The literal meaning of literally, which enters English around 1584 at a time when the vocabulary was really exploding, is ‘by the letters.’ The word comes from Latin littera, which means ‘letter,’ as in the letters of the alphabet, so writing something out literally meant writing it letter by letter. But by 1646 literally had developed its first extended sense, ‘word for word.’ A literal translation is one done word for word, not letter by letter. And by the 19th century Byron uses literally to mean something even more general, ‘a faithful rendering.’ His poem “Churchill’s Grave, a fact literally rendered” (1813) may be a faithful rendering of what Byron saw when he visited the poet Charles Churchill’s grave, but its use of literally is undeniably figurative. This sense of ‘faithful rendering’ is what people who insist on a literal reading of sacred texts or the constitution mean: it’s a figurative use of literal to mean ‘faithful to the original intent,’ assuming such intent can ever be determined.

Today few people use literally

By: Kirsty,

on 10/28/2010

Blog:

OUPblog

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

english,

oed,

ladder,

catalogue,

Early Bird,

supplement,

elizabeth knowles,

researcher,

how to read a word,

frustrating—occasionally,

bodleian,

knowles,

Reference,

UK,

language,

words,

Lexicography,

Featured,

Add a tag

By Elizabeth Knowles

When I began working for Oxford Dictionaries over thirty years ago, it was as a library researcher for the Supplement to OED. Volume 3, O–Scz, was then in preparation, and the key part of my job was to find earlier examples of the words and phrases for which entries were being written. Armed with a degree in English (Old Norse and Old English a speciality) and a diploma in librarianship, I was one of a group of privileged people given access to the closed stacks of the Bodleian Library. For several years the morning began with an hour or so consulting the (large, leather-bound volumes of the) Bodleian catalogue, followed by descent several floors underground to track down individual titles, or explore shelves of books on particular topics. Inevitably, you ended up sitting on the floor leafing through pages, looking for that particular word. The hunt could sometimes be frustrating—occasionally you reached a point where it was clear that you had exhausted all the obvious routes, and only chance (or possibly six months’ reading) would take you further. But it was never dull, and the excitement of tracking down your quarry was only enhanced by the glimpses you had on the way of background information, or particular contexts in which a word had been used. Serendipity was never far removed.

The purpose, of course, was to supply the lexicographers working on the Supplement with the raw material on which the finished entry in its structured and polished form would be based. Not all the information you gained during the search, therefore, would appear in the finished entry, and some of the contextual information (for example, other names for the same thing at a particular period, or even the use of the word by a particular person) was not necessarily directly relevant. But that did not mean that it often wasn’t interesting and thought-provoking for the researcher.

At the time (the late 1970s) research of this kind was carried out in what we would now call hard copy. Entries in the library catalogue might lead to a three-volume eighteenth-century novel, or the yellowed pages of a nineteenth-century journal or newspaper. It followed, therefore, that someone who wanted to research words in this way needed what I had the luck to have: access to the shelves of a major library. At the end of the first decade of the twenty-first century, all that has changed. We still (of course, and thankfully) have excellent dictionaries which can be our first port of call, and we still have library catalogues to guide us. But these resources, and many others, are now online, allowing us to sit in our own homes and carry out the kind of searches for which I had to spend several hours a day underground. With more and more early printed sources becoming digitally available, we can hope to scan the columns of early newspapers, or search the texts of long-forgotten, once popular novels and memoirs. Specialist websites offer particular guidance in areas such as regional forms of English.

The processes for searching in print and online are at once similar, and crucially different. In both cases, we need to formulate our question precisely: what exactly do we want to know? What clues do we already have? A systematic search by traditional means might be compared with climbing a ladder towards an objective—and occasionally finding that the way up is blocked. There are no further direct steps. Online searching always has the possibility that a search will bring up the key term in association with something (a name, another expression), which can start you off down another path—perhaps the equivalent to stepping across to a parallel ladder which will then take you higher.

There has never been a time at which there have been richer resources for the would-be word hunter to explore, and there are no limits to the questions that can

By: Lauren,

on 10/27/2010

Blog:

OUPblog

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

A-Featured,

Oxford Etymologist,

Lexicography,

word origins,

anatoly liberman,

rum,

pay through the nose,

David Halberstam,

full nine yards,

pizzazz,

Add a tag

By Anatoly Liberman

Introduction. In 1984, old newspapers were regularly rewritten, to conform to the political demands of the day. With the Internet, the past is easy to alter. In a recent post, I mentioned C. Sweet, the man who discovered the origin of the word pedigree, and added (most imprudently) that I know nothing about this person and that he was no relative of the famous Henry Sweet. Stephen Goranson pointed out right away that in Skeat’s article devoted to the subject, C. was expanded to Charles and that Charles Sweet was Henry’s brother. I have the article in my office, which means I, too, at one time read it and knew who C. Sweet was. Grieved and embarrassed, I asked Lauren Appelwick, my kind OUP editor, to expunge the silly phrase. She doctored the text, and I was left holding the bag, but grateful to my friendly correspondent and to the volatility of digital means.

Words and Phrases

Pay through the nose. Stephen Goranson also had some doubts about the explanation of this idiom that I dug up in Notes and Queries and called my attention to an earlier publication. This time he did not catch me off guard. I have the previous note in the same (1898) volume of NQ and two more in my archive. A letter about the origin of pay through the nose appeared in the first issue of that once admirable periodical (1850, p. 421) and contained the following passage: “Paying through the noose gives the idea so exactly, that, as far as the etymology goes, it is explanatory enough. But whether that reading has an historical origin may be another question. It scarcely seems to need one.” Mr. C.W.H., the letter writer, was too optimistic. In October of the same year (p. 348-349), Janus Dousa took up the question and mentioned Odin and his tax. I suggested that the idea of connecting the English idiom with Odin’s tax on the Swedes goes back to Ynglinga saga, but Dousa quotes Jacob Grimm’s book on the legal documents in Old Germanic, which means that the information on the tax became known to the English from Grimm (which makes sense: more people could and still can read German than Old Icelandic). In 1898 (September 17, p. 231), J.H. MacMichael cited the 17th-century phrase bored through the nose “swindled in a transaction.” Bore did mean “cheat, gull” (the earliest citation in the OED is dated 1602; no records of pay through the nose prior to 1666 have been found). However, the connection between bore and nose does not seem to have been steady, and pay through the nose refers to exorbitant payment rather than a fraudulent deal. MacMichael thought that the English idiom “express[ed] payment transacted through an improper channel, as a ‘love’ child is said to come into the world through a side door.” I understand how someone can enter through a side door, but the nose is indeed a most improper channel for paying. The phrase needs a more concrete explanation, and I fail to detect a link between an occasional use of bored through the nose and the well-established combination pay through the nose. The full nine yards. The origin of this phrase has often been investigated. Numerous hypotheses exist, but none is fully convincing.

By: Lauren,

on 10/21/2010

Blog:

OUPblog

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

poodle,

mark peters,

hound,

Nobel Prize,

malcolm gladwell,

nip/tuck,

terrier,

pooches,

terriers,

fx,

james wolcott,

joely richardson,

ocean's eleven,

the sheild,

tv,

Film,

A-Featured,

Lexicography,

Add a tag

By Mark Peters

My newest obsession is Terriers, an FX show created by Ted Griffin (who wrote Ocean’s Eleven) and Shawn Ryan (creator of The Shield, the best TV show ever). This show has deliciously Seinfeldian dialogue, effortless and charming acting, plus plots that are unpredictable and fresh. It’s even heart-wrenching at times, and I didn’t know I had a heart to wrench. This show is wonderful. Of course, no one is watching it.

One reason for the low ratings—suggested by everyone and their schnauzer—is that the title Terriers reveals nothing of what the show is actually about: a former cop and former criminal who have split the difference to become private investigators. That’s true. You won’t find any Wheaton terriers, Jack Russell terriers, or Yorkshire terriers—though a bulldog named Winston is a regular character. But terrier has been describing people as well as pooches for a long time, just like Doberman, pit bull, hound, and especially poodle. As quick as people are to anthropomorphize their dogs, we’re just as fond of poochopomorphizing ourselves. In honor of Terriers, here’s a look at words that have been transmitted from pooches to people.

As for terrier itself, it’s been used literally since the 1400’s and figuratively since the 1500’s. As the owner of a rat terrier, I can vouch for the OED’s definition: “A small, active, intelligent variety of dog, which pursues its quarry (the fox, badger, etc.) into its burrow or earth.” Believe me, if my dog were on the case, I would not want to be a rat, mouse, bunny, Smurf, or mole man. Metaphorical uses from 1622 (“Bonds and bills are but tarriers to catch fools.”) and 1779 (“Hunted…by the terriers of the law.”) show that the title of my new favorite show isn’t breaking any new ground. Terrier-osity, whether found in a dude or dog, is characterized by relentless determination that’s almost creepy: think of a Jack Russell who doesn’t seem aware there’s a world beyond his tennis ball.

As for a dog that is as well-established in language as it is horrible-reputation’d in general, you can’t beat the pit bull. Sarah Palin is synonymous with this breed, but she sure didn’t invent the comparison. A 1987 OED example involved a political hero of Palin’s: “President Reagan accused his Democratic critics in Congress Monday of practicing [sic] ‘pit bull economics’ that would ‘tear America’s future apart’ with reckless fiscal and trade policies.” Later citations mention “pit bull management” and “pit-bull intensity.” FYI, since I am a dog-lover, I have to share this article from Malcolm Gladwell on why pit bulls aren’t as deserving as demonization as you think. As with most dog problems, an idiotic owner is the key ingredient.

The word poodle has been prolific as poodles themselves, who seem to breed with anything that chases a squirrel, and maybe even squirrels themselves. There’s poodle-faker (an old term for a dandy, which feels like an old term itself), poodle parlor (a dog grooming business), and poodle skirt (an unfortunate fad in the fifties). Tony Blair was often described as George W. Bush’s poodle—that meaning of “poodle” is about a hundred years old, and it’s first found here in 1907: “The House of Lords consented… It is the right hon. Gentleman’s poodle. It fetches and carries for him. It barks for him. It bites anybody that he sets it on to.” A similar shade of meaning is used in th

By: Lauren,

on 10/20/2010

Blog:

OUPblog

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

word histories,

brisket,

sandahl,

brjósk,

brechet,

Food and Drink,

Breast,

A-Featured,

Oxford Etymologist,

Lexicography,

word origins,

etymology,

dessert,

anatoly liberman,

sweetbread,

Add a tag

By Anatoly Liberman

It seems reasonable that brisket should in some way be related to breast: after all, brisket is the breast of an animal. But the path leading from one word to the other is neither straight nor narrow. Most probably, it does not even exist. In what follows I am greatly indebted to the Swedish scholar Bertil Sandahl, who published an article on brisket and its cognates in 1964. The Oxford English Dictionary has no citations of brisket prior to 1450, but Sandahl discovered bresket in a document written in 1328-1329, and if his interpretation is correct, the date should be pushed back quite considerably. Before 1535, the favored (possibly, the only) form in English was bruchet(te).

The English word is surrounded with many look-alikes from several languages: Middle French bruchet, brichet, brechet (Modern French bréchet ~ brechet “breastbone”; in French dialects, one often finds -q- instead of -ch-), Breton bruch ~ brusk ~ bresk “breast (of a horse),” along with bruched “breast,” Modern Welsh brysced (later brwysged ~ brysged), and Irish Gaelic brisgein “cartilage (as of the nose).” Then there are German Bries ~ Briesel ~ Brieschen ~ Bröschen “the breast gland of a calf,” Old Norse brjósk “cartilage, gristle,” and several words from the modern Scandinavian languages for “sweetbread” (Swedish bräs, Norwegian bris, and Danish brissel), which, as it seems, belong here too (sweetbread is, of course, not bread: it is the pancreas or thymus, especially of a calf, used as food; -bread in sweetbread is believed to go back to an old word for “flesh”). Many words for “breast” in the languages of the world begin with the grating sound groups br- ~ gr- ~ -khr-, as though to remind us of our breakable, brittle, fragile bones (fraction, fragile, and fragment, all going back to the same Latin root, once began with bhr).

At first blush, brisket, with its pseudo-diminutive suffix, looks like a borrowing from French. But there is a good rule: a word is native in a language in which it has recognizable cognates. To be sure, sometimes no cognates are to be seen or good candidates present themselves in more languages than one, but etymology is not an exact science, and researchers should be thankful for even approximate signposts along the way. In French, bréchet is isolated (and nothing similar has been found in other Romance languages), while in Germanic, brjósk, bris, bräs, and others (see them above) suggest kinship with brisket. Therefore, the opinion prevails that brisket is of Germanic origin. Émile Littré, the author of a great, perennially useful French dictionary, thought that the French word had been borrowed from English during the Hundred Year War (1337-1453), and most modern etymologists tend to agree with him. Then the Celtic words would also be from English (for they too are isolated in their languages), and the etymon of brisket would be either Low (that is, northern) German bröske “sweetbread” or Old Norse brjósk, allied to Old Engl. breosan “break.” The original meaning of brisket may have been “something (easily breakable?) in the breast of a (young?) animal.” If so, contrary to expectation, brisket is not related to breast, for breast appears to have been coined with the sense “capable of swelling,” r

By: Lauren,

on 10/6/2010

Blog:

OUPblog

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

A-Featured,

Oxford Etymologist,

Lexicography,

alcohol,

liquor,

word origins,

etymology,

anatoly liberman,

booze,

drinking,

rum,

Add a tag

By Anatoly Liberman

The idea of this post, as of several others before it, has been suggested by a query from a correspondent. A detailed answer would have exceeded the space permitted for the entire set of monthly gleanings, so here comes an essay on the word rum, written on the first rather than the last Wednesday of October. But before I get to the point, I would like to make a remark on the amnesia that afflicts students of word origins. Etymology is perhaps the only completely anonymous branch of linguistics. When people look up a word, they hardly ever ask who reconstructed its history. Surround seems to be related to round, but it is not. On the other hand, soot does not make us think of sit; yet the two are allied. Obviously, neither conclusion is trivial. Even specialists rarely know the names of the discoverers (for those are hard to trace). Unlike Ohm’s Law or Newton’s laws, etymological knowledge easily becomes faceless common property, a plateau without a single hill to obstruct the view. To be sure, we have great authorities, such as the OED and Skeat, but Murray, Bradley (the OED’s first great editors) and Skeat authored only some of the statements they made. In many cases they depended on the findings of their predecessors. What then was their input? All is either forgotten or falsely ascribed to them. Murray could defend his authorship very well. Skeat, too, in countless letters to the editor, strove (strived: take your pick) for recognition and kept rubbing in the fact that he, rather than somebody else, had elucidated the derivation of this or that word. Rarely, very rarely do dictionaries celebrate individual discovery. Thus, pedigree (which French “lent” to English) means “foot of a crane,” from a three-line mark, like the broad arrow used in denoting succession in pedigrees. This was explained by C. Sweet (no relative of Henry Sweet, the famous philologist and the prototype of Dr. Higgins; I could not find any information on him), and Skeat gave the exact reference to his publication. Something similar, though less spectacular (because the conclusion is still debatable), happened when language historians began to research the history of the noun rum.

The most universal law of etymology is that we cannot explain the origin of a word unless we have a reasonably good idea of what the thing designated by the word means. For quite some time people pointed to India as the land in which rum was first consumed and did not realize that in other European languages rum was a borrowing from English. The misleading French spelling rhum suggested a connection with Greek rheum “stream, flow” (as in rheumatism). According to other old conjectures, rum is derived from aroma or saccharum. India led researchers to Sanskrit roma “water” as the word’s etymon, and this is what many otherwise solid 19th-century dictionaries said. Webster gave the vague, even meaningless reference “American,” but on the whole, the choice appeared to be between East and West Indies. Skeat, in the first edition of his dictionary (1882), suggested Malayan origins (from beram “alcoholic drink,” with the loss of the first syllable) and used his habitual eloquence to boost this hypothesis.

Then The Academy, a periodical that enjoyed well-deserved popularity throughout the forty years of its existence (1869-1910), published the following paragraph. (The Imperial Dictionary [not A Universal Dictionary of the English Language, as Spitzer says] gives it in full, but I suspe

By: Lauren,

on 9/29/2010

Blog:

OUPblog

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

the onion,

A-Featured,

Oxford Etymologist,

Lexicography,

word origins,

anatoly liberman,

sign language,

pronunciation,

word histories,

Add a tag

By Anatoly Liberman

I am looking at the backlog of questions and comments for two months (there were no monthly gleanings at the end of August) and, first of all, want to thank everybody who has read the blog, reinforced my conclusions, disagreed or corrected me, given additional information, and asked questions.

Can American Sign Language (ASL) be viewed as having literacy? Words mean what people make them mean, and perhaps literacy can be understood in senses not familiar to the majority of speakers. The term computer literacy has almost turned literacy into a synonym for skills, and yet literacy presupposes an ability to read and write. Someone who can do neither is illiterate. Oral societies that later introduced a script are sometimes referred to as preliterate. From this point of view, ASL does not look to me as a language having literacy. I am not a specialist in ASL and argue from the position of an outsider. All the deaf and mute Americans I know use English as their medium of written communication, even though they consider ASL their native language.

Is Standard English pronunciation a viable concept? I think it is, even if only to a point. People’s accents differ, but some expectation of a more or less leveled pronunciation (that is, of the opposite of a broad dialect) in great public figures and media personalities probably exists. Jimmy Carter seems to have made an effort to sound less Georgian after he became President. If I am not mistaken, John Kennedy tried to suppress some of the most noticeable features of his Bostonian accent. But perhaps those changes happened under the influence of the new environment. In some countries, the idea of “Standard” has a stronger grip on the public mind than in North America. I have often heard people remarking: “He speaks beautiful French” or “Her Italian is wonderful,” and those remarks referred not only to style and vocabulary but also to the speaker’s delivery. Additionally, some local accents are usually called ugly, though from a linguist’s point of view, an ugly native accent is nonsense.

This brings me to some questions of usage. Discussing lie and lay for the umpteenth time would be even less productive than beating ~ flogging a dead horse. In some areas, the distinction has been lost, and so be it. English has lost so many words in the course of its history that the disappearance of one more will change nothing. So lay back and relax. The same holds for dived/dove, sneaked/snuck, and the rest. I only resent the idea that some tyrants wielding power make freedom loving people distinguish between lie and lay. Editors and teachers should be conservative in their language tastes. In works of fiction, characters are supposed to speak the way they do in real life, but in other situations it may be prudent to lag behind the latest trend as long as several variants coexist.

A curious detail of usage is the word dilemna. Our correspondent asked why several decades ago this form had become current on the East Coast. I confessed that I had never heard about this monster, but later searched the Internet. It turned out that some other people are as ignorant of it as I was, but I discovered that dilemna had invaded the English speaking world from New Zealand to Canada. Some children were even taught to pronounce -mn-. Here is probably a situation that will provoke no disagreement: dilemna is unacceptable. The first suggestion that comes to mind is that someone decided to change the spelling of dilemma under the influence of words like column,

By: Lauren,

on 9/24/2010

Blog:

OUPblog

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

ben daniels band,

benjamin kabak,

charles komanoff,

david barash,

geek out,

gelf magazine,

george goethels,

scott allison,

second avenue sagas,

vincent valk,

podcast,

Sociology,

heroes,

A-Featured,

Lexicography,

A-Editor's Picks,

Psychology,

jeopardy,

geeks,

Jesse Sheidlower,

Naked City,

Sharon Zukin,

mta,

The Oxford Comment,

oxford comment,

naked,

jesse,

sheidlower,

lipton,

barash,

judith,

Add a tag

In the second episode of The Oxford Comment, Lauren Appelwick and Michelle Rafferty celebrate geekdom! They interview a Jeopardy champion, talk sex & attraction with a cockatoo, discover what makes an underdog a hero, and “geek out” with some locals.

Subscribe and review this podcast on iTunes!

Featured in this podcast:

Jesse Sheidlower, Editor-at-Large (North America) of the Oxford English Dictionary, author of The F-Word

* * * * *

Matt Caporaletti, “Advertising Account Supervisor from Westwood, NJ,” Jeopardy champion

* * * * *

David P. Barash and Judith Lipton authors of Payback: Why We Retaliate, Redirect Aggression, and Take Our Revenge

* * * * *

Scott T. Allison and George R. “Al” Goethels, authors of Heroes: What They Do and Why We Need Them. Check out their heroes blog!

By: Lauren,

on 9/17/2010

Blog:

OUPblog

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

phonetics,

humez,

suffix,

phonograph,

short cuts,

alexander humez,

gramophone,

on the dot,

word histories,

diaphone,

zettler,

hypophone,

overloading,

polysemic,

phone,

A-Featured,

Lexicography,

Add a tag

By Alexander Humez

Phone (from Greek φωνή ’sound [of the voice], voice, sound, tone’) shows up in English as a prefix (in, e.g., phonograph), a root form (in, e.g., phonetics), a free-standing word (phone), and as a suffix (in, e.g., gramophone) of which A. F. Brown lists well over a hundred in his monumental Normal and Reverse English Word List, though considering that -phone in the sense of “-speaker of” can be tacked onto the end of any combining root that designates a language (as in Francophone), the list of possibilities is considerably greater.

Urdang, Humez, and Zettler in their Suffixes and Other Word-Final Elements of English distinguish among four senses in which the suffix -phone is used (six for -phonic), an overloading that has occasionally resulted in polysemy, where a word has come to have multiple meanings, whether through semantic evolution (e.g., telephone, which has come some distance from its original meaning, now no longer in use), independent invention (e.g., hypophone, which was coined by two different people to mean two very different things), or different etymological histories (e.g., diaphone, in which the -phone of one has a different immediate derivation from that of the other). Follow THIS LINK for a short list of polysemic words ending in -phone, each of which is accompanied by three examples or definitions, two of which are correct and the other of which is bogus. See if you can identify the phonies.

Alexander Humez is the co-author of Short Cuts: A Guide to Oaths, Ring Tones, Ransom Notes, Famous Last Words, and Other Forms of Minimalist Communication with his brother, Nicholas Humez, and Rob Flynn. The Humez brothers also collaborated on Latin for People, Alpha to Omega, A B C Et Cetera, Zero to Lazy Eight (with Joseph Maguire), and On the Dot. To see Humez’s previous posts, click here.

By: Lauren,

on 8/26/2010

Blog:

OUPblog

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

A-Featured,

Lexicography,

hermaphrodite,

gender equality,

Dennis Baron,

gender politics,

gender-neutral,

grammar rules,

pronoun,

Add a tag

By Dennis Baron

Every once in a while some concerned citizen decides to do something about the fact that English has no gender-neutral pronoun. They either call for such a pronoun to be invented, or they invent one and champion its adoption. Wordsmiths have been coining gender-neutral pronouns for a century and a half, all to no avail. Coiners of these new words insist that the gender-neutral pronoun is indispensable, but users of English stalwartly reject, ridicule, or just ignore their proposals.

Recently, Guardian columnist Lucy Mangan called for a gender-neutral pronoun:

The whole pronouns-must-agree-with-antecedents thing causes me utter agony. Do you know how many paragraphs I’ve had to tear down and rebuild because you can’t say, “Somebody left their cheese in the fridge”, so you say, “Somebody left his/her cheese in the fridge”, but then you need to refer to his/her cheese several times thereafter and your writing ends up looking like an explosion in a pedants’ factory? … I crave a non-risible gender-neutral (not “it”) third person sing pronoun in the way normal women my age crave babies. The Guardian, July 24, 2010, p. 70

English is a language with a vocabulary so large that every word in it seems to have a dozen synonyms, and yet this particular semantic black hole remains unfilled. As Tom Utley complains in the Daily Mail,

It never ceases to infuriate me, for example, that in this cornucopia of a million words, there’s no simple, gender-neutral pronoun standing for ‘he-or-she’.

That means we either have to word our way round the problem by using plurals – which don’t mean quite the same thing – or we’re reduced to the verbose and clunking construction: ‘If an MP steals taxpayers’ money, he or she should be ashamed of himself or herself.’ (‘Themselves’, employed to stand for a singular MP, would, of course, be a grammatical abomination). London Daily Mail, June 13, 2009

The traditional gender agreement rule states that pronouns must agree with the nouns they stand for both in gender and in number. A corollary requires the masculine pronoun when referring to groups comprised of men and women. But critics argue that such generic masculines – for example, “Everyone loves his mother” – actually violate the gender agreement part of the pronoun agreement rule. And they warn that the common practice of using they to avoid generic he violates number agreement: in “Everyone loves their mother,” everyone is singular and their is plural. Only a new pronoun, something like ip, coined in 1884, can save us from the error of the generic masculine or the even worse error of singular “they.”

Such forms as co, xie, per, and en abound in science fiction, where gender is frequently bent, and they pop up with some regularity in online transgender discussion groups, where the traditional masculine and feminine pronouns are out of place. But today’s word coiners seem unaware that gender-neutral English pronouns have been popping up, then disappearing without much trace, since the mid-nineteenth century.

According to an 1884 article in the New-York Commercial Advertiser<

By: Lauren,

on 8/25/2010

Blog:

OUPblog

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

fuck,

f-word,

fogger,

pettifogger,

A-Featured,

Oxford Etymologist,

Lexicography,

Dictionaries,

word origins,

etymology,

anatoly liberman,

Add a tag

By Anatoly Liberman

How did pettifoggers get their name? Again and again we try to discover the origin of old slang, this time going back to the 16th century. Considering how impenetrable modern slang is, we should always be ready to stay with extremely modest conclusions in dealing with the popular speech of past epochs. In this blog, the essays on chestnut, tip, humbug, scoundrel, kybosh, and the much later copasetic and hubba-hubba, among others, have revealed some of the difficulties an etymologist encounters in dealing with such vocabulary.

In regards to the sphere of application, pettifogger belongs with huckster, hawker, and their synonym badger. All of them are obscure, badger being the hardest. Pettifoggers, shysters, and all kinds of hagglers have humble antecedents and usually live up to their names, which tend to be coined by their bearers. At one time it was customary to say that words like hullabaloo are as undignified as the things they designate. Today we call a marked correspondence between words’ meaning and their form iconicity, admire their raciness, and organize international conferences to celebrate their existence. Pettifogger is unlike hullabaloo (to which, incidentally, another post was once devoted), but there is something mildly “iconic” in it: petty refers to smallness, while fogger resembles f—er and thus commands minimal respect. As we will see, the resemblance is not fortuitous.

The Low (= Northern) German or Dutch origin of fogger is certain. The early Modern Dutch form focker was Latinized as foggerus, with -gg- in the middle. German has Focker, Fogger, and Fucker, none having any currency outside dialects. The OED cites them from the Grimms’ multivolume dictionary. (As is known, the OED had to bow to the morals of its time and excluded “unprintable” words, but in the entries where no one would look for them, offensive forms appeared: such is a mention of German fucker, with lower-case f, under fogger, and of windfucker “kestrel.”) Although today Dutch fokken means “to breed cattle,” its predecessor had a much broader semantic spectrum: “cheat; flee; adapt, adjust; beseem; push; collect things secretly”—an odd array of seemingly incompatible senses. Most likely, “push” was the starting point; hence “adjust,” then “adjust properly” (“beseem”). But despite doing things as it beseems or behooves, pushing suggested underhand dealings (“collect things secretly; cheat,” and even “flee,” evidently from acting in a hurry and clandestinely).

There can be little doubt that the English F-word is also a borrowing of a Low German verb whose basic meaning was, however, “move back and forth” rather than “push.” “Deceive” and “copulate” often appear as senses of one and the same verb. Fokken is a member of a large family. All over the Germanic speaking world we find ficken, ficka, fikla (compare Engl. fickle), fackeln, fickfacken, fucken, fuckeln, and so forth, meaning approximately the same: “make quick, short movements; hurry up; run aimlessly back and forth; shilly-shally; cheat (especially in games).” Unlike German, Dutch, and Scandinavian, English had almost no words with the fi(c)k ~ fa(c)k ~ fu(c)k root, so that fogger is rather obviously not native. The same, I believe, is true of several Romance words like Italian ficcare “copulate,” though in the latest dictionaries it is said to be unrelate

Posted on 8/20/2010

Blog:

OUPblog

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

mcdonald's,

Business,

Current Events,

starbucks,

language,

borders,

A-Featured,

Lexicography,

barista,

target,

jargon,

Dennis Baron,

jetblue,

corporate speak,

new york post,

Add a tag

By Dennis Baron

Apparently an English professor was ejected from a Starbucks on Manhattan’s Upper West Side for – she claims – not deploying Starbucks’ mandatory corporate-speak. The story immediately lit up the internet, turning her into an instant celebrity. Just as Steven Slater, the JetBlue flight attendant who couldn’t take it anymore, became the heroic employee who finally bucked the system when he cursed out nasty passengers over the intercom and deployed the emergency slide to make his escape, Lynne Rosenthal was the customer who cared so much about good English that she finally stood up to the coffee giant and got run off the premises by New York’s finest for her troubles. Well, at least that’s what she says happened.

According to the New York Post, Rosenthal, who teaches at Mercy College and has an English Ph.D. from Columbia, ordered a multigrain bagel at Starbucks but “became enraged when the barista at the franchise” asked, “Do you want butter or cheese?” She continued, “I refused to say ‘without butter or cheese.’ When you go to Burger King, you don’t have to list the six things you don’t want. Linguistically, it’s stupid, and I’m a stickler for correct English.” When she refused to answer, she claims that she was told, “You’re not going to get anything unless you say butter or cheese!” And then the cops came.

Stickler for good English she may be, but management countered that the customer then made a scene and hurled obscenities at the barista, and according to the Post, police who were called to the scene insist that no one was ejected from the coffee shop.

I too am a professor of English, and I too hate the corporate speak of  “tall, grande, venti” that has invaded our discourse. But highly-paid consultants, not minimum-wage coffee slingers, created those terms (you won’t find a grande or a venti in Italian coffee bars). Consultants also told “Starbuck’s” to omit the apostrophe from its corporate name and to call its workers baristas, not coffee-jerks.

“tall, grande, venti” that has invaded our discourse. But highly-paid consultants, not minimum-wage coffee slingers, created those terms (you won’t find a grande or a venti in Italian coffee bars). Consultants also told “Starbuck’s” to omit the apostrophe from its corporate name and to call its workers baristas, not coffee-jerks.

My son was a barista (should that be baristo?) at Borders (also no apostrophe, though McDonald’s keeps the symbol, mostly) one summer, and many of my students work in restaurants, bars, and chain retail stores. The language that employees of the big chains use on the job is carefully scripted and choreographed by market researchers, who insist that employees speak certain words and phrases, while others are forbidden, because they think that’s what moves “product.” Scripts even tell workers how and where and when to move and what expression to paste on their faces. Employees who go off-script and use their own words risk demerits, or worse, if they’re caught by managers, grouchy customers, or the ubiquitous secret shoppers who ride the franchise circuit looking for infractions.

I’m no fan of this corporate scripting. Calling customers “guests” and employees “associates” doesn’t mean I can treat Target like a friend’s living room or that the clerks who work there are anything but low-level employees who associate with one another, not with corporate vice presidents. I don’t think this kind of language-enforcement increases sales or

By: Lauren,

on 8/12/2010

Blog:

OUPblog

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

Reference,

penn jillette,

humez,

pictographs,

rebus,

phonograms,

overworked,

i love my dog,

pictogram,

play on words,

short cuts,

visual puzzle,

A-Featured,

Lexicography,

Dictionaries,

Leisure,

Add a tag

By Alexander Humez

Largely gone from the funny pages but alive and well on the rear bumper of the car, the rebus is a visual puzzle that, in its various forms, encapsulates the history of alphabetic writing from ideograms (pictures designating concepts or things) to pictographs (pictures representing specific words or phrases) to phonograms (pictures representing specific sounds or series of sounds). Dictionaries struggle to define the term in such a way as to capture the range of shapes a rebus can take, typically focussing on its pictographic and phonogrammic attributes, forgoing mention of the ideographic. For example, the OED defines rebus as “a. An enigmatical representation of a name, word, or phrase by figures, pictures, arrangement of letters, etc., which suggest the syllables of which it is made up. b. In later use also applied to puzzles in which a punning application of each syllable of a word is given, without pictorial representation.”

The origin of the word is a matter of some debate (nicely summarized by Maxime Préaud in his “Breve histories du rebus francis” and treated at greater length by Card and Margo lin in their Rebus de la Renaissance: Des images quai par lent), but whatever its pedigree, the thing itself has been a popular item since at least the end of the fifteenth century. In his treatise on orthography of 1526 (Champ Fleur), Geoffroi Tory notes the practice of “jokers and young lovers” who make up “devices,” such as a small a inside a large g to signify “Jay grant appetit,” that is, “g grand a petit,” which he decries because, he says, such practices often result in sloppy penmanship and pronunciation. After giving a few more examples of “devices” made up of letters, he goes on to say that there are devices that aren’t made up of “significative letters,” but, rather, are made up of “images which signify the fantasies of their Author, & this is called a Rebus,” of which he describes (but does not depict) some examples.

The simplest rebuses are those consisting only of letters: IOU, the (in)famous title of Marcel Duchamp’s moustached Mona Lisa “l.h.o.o.q.” (Elle a chaud au cul, literally something like ‘Her ass is hot,’ figuratively, ‘She’s horny’), and such staples of modern day texting as CUL8R or French @2m1 (à deux m un, i.e., “à demain” ‘[See you] tomorrow’).

An elaboration of the all-character rebus is exemplified by the following, the first in English, the second in French (cited by Estienne Tabouret des Accords in his Les Bigarrures et Touches du Seigneur des Accords—roughly, ‘Lord des Accord’s Medley of Colors and Dabs’—which appeared in several editions in the late 16 th century):

(“I am overworked and underpaid”) and

(Le sous het en sur pens le

0 Comments on Are you ready for rebuses? as of 1/1/1900

By Anatoly Liberman

Tier, tear (noun), tear (verb), tare, wear, weary, and other weird words

Even the staunchest opponents of spelling reform should feel dismayed at seeing the list in the title of this essay. How is it possible to sustain such chaos, now that sustainable has become the chief buzzword in our vocabulary? Never mind foreigners—they chose to study English and should pay for their decision, but what have native speakers done to deserve this torture? The answer is clear: they are too loyal to a fickle tradition.

Nowadays not only the “public” but also prospective linguists have insufficient exposure to the history of language, while English majors, who are taught to view every text through multiple “lenses” (another great academic buzzword), may graduate without any knowledge of the development of English, for no optical tools have been invented for examining this subject. Even the few graduate students who choose the past stages of language as their main area of expertise and risk staying independent scholars (this means “unemployed”) for the rest of their lives will usually study Old and Middle English but come away with the haziest idea of what happened between the 16th and the 19th century, though it was during the early modern period that the system of English vowels was hit the hardest. This holds not only for the so-called Great Vowel Shift that gave long a, e, i, o and u their present values and drove a wedge between the pronunciation of letter names in English and the rest of Europe. All vowels before r were also caught in this storm

To begin with, er turned into ar. We are dimly aware of this process because we still have Clark, parson, and varsity alongside clerk, person, and university. Providentially, some words like star and far are now spelled with ar, but in the past they too had er. Later, er reemerged in English and stayed unchanged for some time. Our vowels are still called short and long, but these terms are misleading, because the sounds designated by a, e, i, o, and u in mat, pet, bit, not, and us are not simply shorter than those in mate, Pete, bite, note, and use: they are quite different. One gets an idea of short versus long (as in Latin, Italian, Finnish, Swedish, and many other languages), while comparing Engl. wood and wooed. Several pairs of such vowels existed in early English. One more factor played an outstanding role in the history of words like tier and tear. There were two long e’s: closed (approximately as in pet) and mid-open (approximately like e in where), but having greater duration than in those modern words.

Although neither of the two e’s has continued into present day English unchanged, we can guess which stood where while comparing the spelling of meet and meat. To the extent that our erratic spelling reflects an older norm, ee points to closed long e and ea to its more open partner. But in the absence of a recognized standard, many words were not spelled in accordance with their pronunciation. Besides, as far as we can judge, a great deal of vacillation characterized the use of mid-open and closed long e. Apparently, the two vowels we

By Anatoly Liberman

Part 1 appeared long ago and dealt with blackguard, blackleg, and blackmail, three words whose history is unclear despite the seeming transparency of their structure. Were those guards as black as they were painted? Who had black legs, and did anyone ever receive black mail? As I then noted, the etymology of compounds may be evasive. One begins with obvious words (doormat, for example), passes by dormouse with its impenetrable first element, wonders at moonstone (does it have anything to do with the moon?), moonlighting, and moonshine (be it “foolish talk” or “illegally distilled whiskey”), experiences a temporary relief at the sight of roommate, and stops in bewilderment at mushroom. The way from dormouse to mushroom is full of pitfalls. (And shouldn’t pitfall be fallpit? Originally a pitfall was a trapdoor, a snare, a device for catching birds, but then why pit?). So-called disguised, or simplified, compounds, like lord and lady (at one time they consisted of two elements) will not interest us today.

Some compounds are so simple and we learn them so early in life that their incongruity never bothers us. Why is the opposite of sunrise sunset rather than sunsit? Even the OED is not quite sure. Regardless of whether sunset is a combination of two nouns (sun + set) or of a noun with a verb in the subjunctive, we expect sit because the sun “sits down” in the west (no one sets it). Sit and set have often been confused, though the result of the confusion is not as catastrophic as with lie and lay. Recently one could hear on Good Morning, America a responsible person’s advice to an actress to lay low; the speaker may have grown up in the Midwest, but the lie/lay game has also been attested in several British dialects, and from there it was presumably imported to the New World. Drawback, we discover, was first used as a banking term; it referred to a sum paid as duty, which is quite natural: we can still overdraw our account; the meaning “an amount of import duty paid back when goods are exported again” continues into the present. At the end of the 18th century, drawback was used in bookselling with the sense “rebate, discount.” Drawback “a weak point, disadvantage, deficiency” appeared in texts and probably in speech early in the 18th century, and we no longer “hear” its separate parts. Whatever the details of the convoluted history of bedridden (from Old Engl. bedrede), another deceptive compound, a bedridden person is a poor rider, and a bed is not a horse, but we have heard the word too often to react to the incongruous metaphor.

A most curious adjective is beetle-browed “with bushy, shaggy, or prominent eyebrows.” Hardly anyone uses it, but it is probably still recognizable without a dictionary. The word goes back to Middle English, and the question is: “Why beetle?” Some older scholars did not realize that initially brow meant only “eyebrow” (like German Braue), not “forehead,” so the gloss “with a brow overhanging like that of a beetle” can be dismissed (also, an average beetle does not have much of a brow, does it?). Beetle is, etymologically speaking, a “biter” and is thus related to bite and bitter, because a bitter thing “bites.” Middle English had the adjective bitel “biting,” with a suffix, as in fickle, brittle, and nimble. For this reason, Skeat, in the first edition of his dic

Last Spring the New York Times reported that more and more grammar vigilantes are showing up on Twitter to police the typos and grammar mistakes that they find on users’ tweets. According to the Times, the tweet police “see themselves as the guardians of an emerging behavior code: Twetiquette,” and some of them go so far as to write algorithms that seek out tweets gone wrong (John Metcalfe,

Last Spring the New York Times reported that more and more grammar vigilantes are showing up on Twitter to police the typos and grammar mistakes that they find on users’ tweets. According to the Times, the tweet police “see themselves as the guardians of an emerging behavior code: Twetiquette,” and some of them go so far as to write algorithms that seek out tweets gone wrong (John Metcalfe,

“tall, grande, venti” that has invaded our discourse. But highly-paid consultants, not minimum-wage coffee slingers, created those terms (you won’t find a grande or a venti in Italian coffee bars). Consultants also told “Starbuck’s” to omit the apostrophe from its corporate name and to call its workers baristas, not coffee-jerks.