new posts in all blogs

Viewing: Blog Posts Tagged with: bryant, Most Recent at Top [Help]

Results 1 - 6 of 6

How to use this Page

You are viewing the most recent posts tagged with the words: bryant in the JacketFlap blog reader. What is a tag? Think of a tag as a keyword or category label. Tags can both help you find posts on JacketFlap.com as well as provide an easy way for you to "remember" and classify posts for later recall. Try adding a tag yourself by clicking "Add a tag" below a post's header. Scroll down through the list of Recent Posts in the left column and click on a post title that sounds interesting. You can view all posts from a specific blog by clicking the Blog name in the right column, or you can click a 'More Posts from this Blog' link in any individual post.

By: Alice,

on 8/4/2014

Blog:

OUPblog

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

Books,

Literature,

shakespeare,

ammon,

shea,

OWC,

ammon shea,

charlie,

Oxford World's Classics,

durrell,

king lear,

lear,

bryant,

Bryant Park,

Humanities,

*Featured,

Bryant Park summer reading,

novobatzky,

couresty,

Add a tag

Each summer, Oxford University Press USA and Bryant Park in New York City partner for their summer reading series Word for Word Book Club. The Bryant Park Reading Room offers free copies of book club selections while supply lasts, compliments of Oxford University Press, and guest speakers lead the group in discussion. On Tuesday 5 August 2014, Ammon Shea, author of Reading the OED and Bad English, leads a discussion on Shakespeare’s King Lear.

What was your inspiration for Bad English?

What was your inspiration for Bad English?

I am often guilty of spectacular incompetence when I try to use the English language, and I wanted to find some justification for my poor usage. I am happy to report that we have all been committing unseemly acts with English for many hundreds of years.

Where do you do your best writing?

In library basements, preferably when they are empty of people.

Did you have an “a-ha!” moment that made you want to be a writer?

I hadn’t so much of an ‘a-ha’ moment that made me want to be a writer as I had a series of ‘uh-oh’ moments while doing other things that did not involve writing.

Which author do you wish had been your 7th grade English teacher?

Gerald Durrell

What is your secret talent?

I can distinguish between Sonny Stitt and Charlie Parker, and between Phil Woods and Gene Quill, in under four measures.

What is your favorite book?

Too Loud a Solitude by Bohumil Hrabal.

Who reads your first draft?

My wife reads my first drafts, and, if she is feeling particularly generous, my second and third ones as well.

Do you read your books after they’ve been published?

Not unless I absolutely have to.

Do you prefer writing on a computer or longhand?

I have no marked preference. I will write on whatever is at hand, and this ranges from cellular telephones to antiquated typewriters.

What book are you currently reading? (And is it in print or on an e-Reader?)

Charlie and the Chocolate Factory, with my son, and in print.

What word or punctuation mark are you most guilty of overusing?

I reject the premise of this question.

If you weren’t a writer, what would you be?

Someone who wished he was a writer.

Ammon Shea is the author of Bad English, Reading the OED, The Phone Book, Depraved English (with Peter Novobatzky), and Insulting English (with Peter Novobatzky). He has worked as consulting editor of American dictionaries at Oxford University Press, and as a reader for the North American reading program of the Oxford English Dictionary. He lives in New York City with his wife (a former lexicographer), son (a potential future lexicographer), and two non-lexical dogs.

For over 100 years Oxford World’s Classics has made available the broadest spectrum of literature from around the globe. Each affordable volume reflects Oxford’s commitment to scholarship, providing the most accurate text plus a wealth of other valuable features, including expert introductions by leading authorities, voluminous notes to clarify the text, up-to-date bibliographies for further study, and much more. You can follow Oxford World’s Classics on Twitter and Facebook. Read previous interviews with Word for Word Book Club guest speakers.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only literature articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Image couresty of Jenny Davidson.

The post 10 questions for Ammon Shea appeared first on OUPblog.

By: Julia Callaway,

on 7/15/2014

Blog:

OUPblog

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

Books,

History,

american history,

charity,

America,

marriage,

LGBT,

lgbtq,

gay rights,

bryant,

same-sex marriage,

drake,

Editor's Picks,

*Featured,

sylvia,

Charity and Sylvia: A Same-Sex Marriage in Early America,

Charity Bryant,

Rachel Hope Cleves,

Sylvia Drake,

hurlburt,

sylvia’s,

of charity,

cleves,

Add a tag

By Rachel Hope Cleves

Same-sex marriage is having a moment. The accelerating legalization of same-sex marriage at the state level since the Supreme Court’s June 2013 United States v. Windsor decision, striking down the Defense of Marriage Act, has truly been astonishing. Who is not dumbstruck by the spectacle of legal same-sex marriages performed in a state such as Utah, which criminalized same-sex sexual behavior until 2003? The historical whiplash is dizzying.

Daily headlines announcing the latest changes to the legal landscape of same-sex marriage are feeding public curiosity about the history of such unions, and several of the books that top the “Gay & Lesbian History” bestsellers lists focus on same-sex marriage. However, they tend to focus on the immediate antecedents for today’s legal decisions, rather than the historical roots of the issue.

At first consideration, it may seem anachronistic to describe a same-sex union from the early nineteenth century as a “marriage,” but this is the language that several who knew Charity Bryant (1777-1851) and Sylvia Drake (1784-1868) used at the time. As a young boy growing up in western Vermont during the antebellum era, Hiram Harvey Hurlburt Jr. paid a visit to a tailor shop run by the two women to order a suit of clothes made. Noticing something unusual about the women, Hurlburt asked around town and “heard it mentioned as if Miss Bryant and Miss Drake were married to each other.” Looking back from the vantage of old age, Hurlburt chose to include their story in a handwritten memoir he left to his descendants. Like homespun suits, the women were a relic of frontier Vermont, which was receding swiftly into the distance as the twentieth century surged forward. Once upon a time, Hurlburt recalled for his relatives, two women of unusual character could be known around town as a married couple.

There were many who agreed with Hurlburt. Charity Bryant’s sister-in-law, Sarah Snell Bryant, mother to the beloved antebellum poet and journalist William Cullen Bryant, wrote to the women “I consider you both one as man and wife are one.” The poet himself described his Aunt Sylvia as a “fond wife” to her “husband,” his Aunt Charity. And Charity called Sylvia her “helpmeet,” using one of the most common synonyms for wife in early America.

The evidence that Charity and Sylvia possessed a public reputation as a married couple in their small Vermont town, and among the members of their family, goes a long way to constituting evidence that their union should be labeled as a same-sex marriage and seen as a precedent for today’s struggle. In the legal landscape of the early nineteenth century, “common law” marriages could be verified based on two conditions: a couple’s public reputation as being married, and their sharing of a common residence. Charity and Sylvia fit both those criteria. After they met in the spring of 1807, while Charity was paying a visit to Sylvia’s hometown of Weybridge, Vermont, Charity decided to rent a room in town and invited Sylvia to come live with her. The two commenced their lives together on 3 July 1807, a date that the women regarded as their anniversary forever after. The following year they built their own cottage, initially a twelve-by-twelve foot room, which they moved into on the last day of 1808. They lived there together for the rest of their days, until Charity’s death in 1851 from heart disease. Sylvia lasted another eight years in the cottage, before moving into her older brother’s house for the final years of her life.

The grave of Charity Bryant and Sylvia Drake. Photo by Rachel Hope Cleves. Do not use without permission.

Of course, Charity and Sylvia did not fit one very important criterion for marriage, common-law or statutory: that the union be established between a man and a woman. But then, their transgression of this requirement likened their union to other transgressive marriages of the age: those between couples where one or both spouses were already married, or where one or both spouses were beneath the age of consent at the formation of the union, or where one spouse was legally enslaved. In each of these latter circumstances, courts called on to pass judgment over questions of inheritance or the division of property sometimes recognized the validity of marriages even where the spouses could not legally be married according to statute. Since Charity and Sylvia never argued over property in life, and since their inheritors did not challenge the terms of the women’s wills which split their common property between their families, the courts never had a reason to rule on the legality of the women’s marriage. Ultimately, the question of whether their union constituted a legal marriage in its time cannot be resolved.

Regardless, it is vital that the history of marriage include relationships socially understood to be marriages as well as those relationships that fit the legal definition. Although the legality of same-sex marriage has been the subject of focused attention in the past decade (and the past year especially), we cannot forget that marriage exists first and foremost as a social fact. To limit the definition of marriage entirely to those who fit within its statutory terms would, for example, exclude two and a half centuries of enslaved Americans from the history of marriage. It would confuse law’s prescriptive powers with a description of reality, and give statute even more power than its oversized claims.

Awareness of how hard-fought the last decade’s legalization battle has been makes it difficult to believe that during the early national era two same-sex partners could really and truly be married. However, a close look at Charity and Sylvia’s story compells us to re-examine our beliefs. History is not a progress narrative, we all know. What’s only just become possible now may have also been possible at points in the past. Historians of the early American republic might want to ask why Charity and Sylvia’s marriage was possible in the first decades of the nineteenth century, whether it would have been so forty years later or forty years before, and what their marriage can tell us about the possibilities for sexual revolution and women’s independence in the years following the Revolution. For historians of any age, Charity and Sylvia’s story is a reminder of the unexpected openings and foreclosures that make the past so much more interesting than our assumptions.

Rachel Hope Cleves is Associate Professor of History at the University of Victoria. She is author of Charity and Sylvia: A Same-Sex Marriage in Early America.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only American history articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

The post Same-sex marriage now and then appeared first on OUPblog.

By: Alice,

on 7/7/2014

Blog:

OUPblog

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

summer reading,

rebecca,

OWC,

finn,

Middlemarch,

Oxford World's Classics,

mead,

bryant,

Bryant Park,

Humanities,

george eliot,

huckleberry,

*Featured,

Word for Word Book Club,

My Life in Middlemarch,

Rebecca Mead,

prochnik,

elisabeth,

Books,

Literature,

Add a tag

Each summer, Oxford University Press USA and Bryant Park in New York City partner for their summer reading series Word for Word Book Club. The Bryant Park Reading Room offers free copies of book club selections while supply lasts, compliments of Oxford University Press, and guest speakers lead the group in discussion. On Tuesday 8 July 2014, Rebecca Mead, author of My Life in Middlemarch, leads a discussion on George Eliot’s Middlemarch.

What was your inspiration for choosing Middlemarch?

What was your inspiration for choosing Middlemarch?

I first read Middlemarch at seventeen, and have read it roughly every five years or so since, my emotional response to it evolving at each revisiting. In my forties, I decided to spend more time with the book and to explore the ways in which it seems to have woven itself into my life: hence my own book, My Life In Middlemarch.

Did you have an “a-ha!” moment that made you want to be a writer?

Not exactly, but getting my first story published in a national newspaper at the age of eleven in a contest for young would-be journalists—and getting paid for it—must have been a motivating factor.

Which author do you wish had been your 7th grade English teacher?

The best book I can think of that gets into the mind of a thirteen or fourteen year old is Huckleberry Finn, so please may I have Mark Twain?

What is your secret talent?

I used to be able to charm children with my ability to walk on my hands. Then I had my own child, and ever since my balance hasn’t been what it used to be. Luckily, my son doesn’t require charming.

With what word do you most identify?

“perhaps”

Rebecca Mead is a staff writer for The New Yorker. She is the author of My Life in Middlemarch and One Perfect Day: The Selling of the American Wedding. She lives in Brooklyn.

For over 100 years Oxford World’s Classics has made available the broadest spectrum of literature from around the globe. Each affordable volume reflects Oxford’s commitment to scholarship, providing the most accurate text plus a wealth of other valuable features, including expert introductions by leading authorities, voluminous notes to clarify the text, up-to-date bibliographies for further study, and much more. You can follow Oxford World’s Classics on Twitter and Facebook. Read previous interviews with Word for Word Book Club guest speakers.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only literature articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Image credit: Rebecca Mead. Photo by Elisabeth C. Prochnik. Courtesy of Rebecca Mead.

The post Five questions for Rebecca Mead appeared first on OUPblog.

By: Lauren,

on 5/24/2011

Blog:

OUPblog

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

*Featured,

the pale king,

Matthew Gallaway,

The Metropolis Case,

gallaway,

Seth Colter Walls,

word for word,

30pm,

avenues,

hagar’s,

overusing,

45pm,

free books,

blog,

Literature,

Current Events,

New York City,

book club,

Leisure,

matthew,

Reading Room,

bryant,

Bryant Park,

Add a tag

Have you heard the Word…for Word? Oxford University Press is proud to partner with the Bryant Park Reading Room in support of the Word for Word Book Club. The series kicks off today, with six more Clubs scheduled throughout the summer. Be sure to stop by the Reading Room early for a FREE* copy of the book club selections.

The Bryant Park Blog posed to following questions to resident OUP Law Editor and acclaimed novelist Matthew Gallaway, author of The Metropolis Case, who will lead today’s Word for Word Book Club, along with Seth Colter Walls. This first discussion of the season will focus on The Pale King, the posthumously published novel by David Foster Wallace.

You can meet Matthew Gallaway today, May 24th, at 12:30pm in beautiful Bryant Park. The outdoor Reading Room is just off 42nd St, between 5th and 6th Avenues in New York City. In the event of rain, discussions will relocate to the The General Society of Mechanics and Tradesmen, 20 West 44th Street (between 5th & 6th Avenues).

Where do you do your best writing? In airports.

Where do you do your best writing? In airports.

Did you have an “a-ha!” moment that made you want to be a writer? When I read Against The Grain, by JK Huysmans.

Which author do you wish had been your 7th grade English teacher? Oscar Wilde.

What is your secret talent? I’m very good at growing ferns.

What is your favorite book? In Search of Lost Time, by Marcel Proust.

Who reads your first draft? My partner Stephen.

Do you read your books after they’ve been published? No.

What book are you currently reading? All Aunt Hagar’s Children, by Edward P. Jones

What word or punctuation mark are you most guilty of overusing? The em-dash.

If you weren’t a writer, what would you be? A gardener.

For more information on Matthew and his new book, check out this episode of The Oxford Comment podcast.

*Yes, by “free” we mean free. Actually, truly, really free. Register to reserve your complimentary copy, or take your chances and get there early; books are available on a first-come-first-serve basis.

Word for Word Book Club

Tuesdays , 12:30pm – 1:45pm

May 24, June 14, June 28, July 12, July 26, August 9, August 23

Reading Room

By: Lauren,

on 2/11/2011

Blog:

OUPblog

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

pirates,

Sports,

Technology,

e-books,

Current Events,

Geography,

Leisure,

paula deen,

pirate,

Egypt,

kobe bryant,

black swan,

bryant,

cairo,

linked up,

*Featured,

Trenta,

frak,

clabwag,

cgpgrey,

cockeyed,

kobe,

Add a tag

It’s been a few weeks since I’ve written a Linked Up, but with releasing a new episode of The Oxford Comment, working “frak” into my daily vocabulary, and trying to keep up on developments in Egypt, I’ve not found the time! Hopefully, today’s will make up for it. Have a wonderful weekend everyone!

P.S. I promised our Twitter followers that if they came up with at least 5 good questions about insects I would have an entomologist answer them, so send in yours!

Apparently Kobe Bryant told Pau Gasol he needed to be more “black swan” on the court. [NYMag]

I was shocked by this: “Vodafone Forced to Send Pro-Government Text Messages in Egypt” [RWW]

There is a wonderful new Paula-Deen-as-hipster meme [Clabwag]

I have a lot of colleagues in the UK, so this “everything you ever wanted to know about the UK/GB/England in five minutes” was very helpful. My favorite (favourite?) part: “BFFs 4EVA USA?” [CGPGrey]

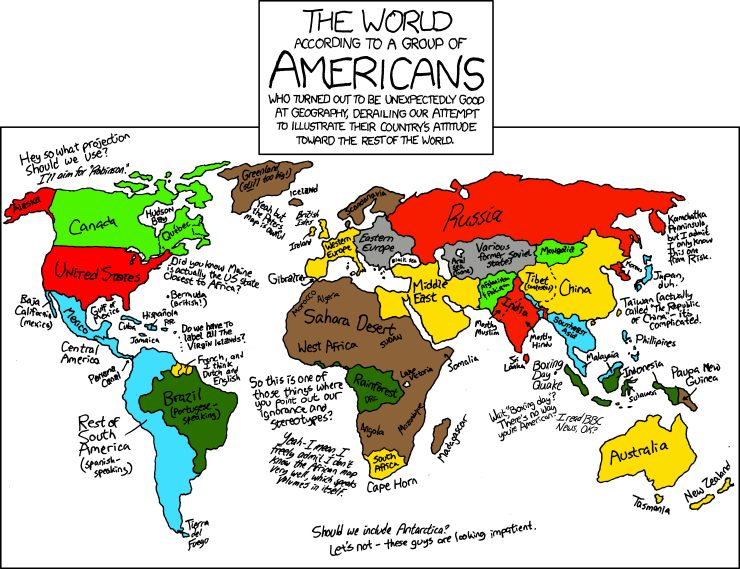

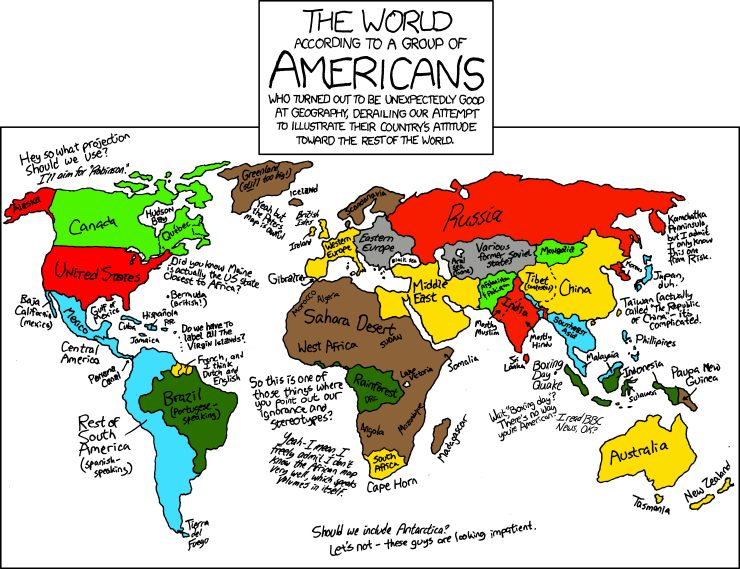

And since we’re on the topic of geography, I might as well present this from XKDC:

Yes, it’s been around for a while, but I think it’s important to remind everyone that you can talk like a pirate on Facebook. [NextWeb]

You got a few minutes to make some fleeting art? Then try this.

If you didn’t see the update to our article “Why the Trenta?” I’m sure you’ll be delighted to learn that Starbucks’ newest size can hold an entire bottle of wine. [Cockeyed]

Oh Apple, you’re so sneaky. [Atlantic]

Protesters are awesome: Egyptian volunteers clean the streets [Good]

And now, an enormous infographic:

By: Rebecca,

on 7/20/2009

Blog:

OUPblog

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

Reading Room,

Bryant,

John R. MacArthur,

MacArthur,

Sawyer,

Harper\ s,

Literature,

Current Events,

Free,

A-Featured,

A-Editor's Picks,

Prose,

Leisure,

OWC,

Bryant Park,

Harper's Magazine,

Reading,

Magazine,

read,

John,

Tom Sawyer,

Mark Twain,

Oxford University Press,

R,

Park,

Tom,

Mark,

lunch,

Room,

Twain,

Add a tag

What are you doing during lunch tomorrow? If it involves sitting at your desk eating a sandwich consider joining us in Bryant Park. Oxford University Press has teamed up with the Bryant Park Reading Room to host a FREE discussion of The Adventures of Tom Sawyer led by John R. MacArthur, publisher of Harper’s Magazine and author, most recently, of You Can’t be President: The Outrageous Barriers to Democracy in America. In the blog post after the break MacArthur introduces us to the relationship between Harper’s and Mark Twain.

So be sure to come to the Bryant Park Reading Room (northern edge of the park), Tuesday, July 21st from 12:30 p.m. to 1:45 p.m. The rain venue (don’t worry we are doing our best no-rain dances) is The General Society of Mechanics and Tradesmen Building, 20 West 44th Street. Sign up in advance and receive a FREE copy of the Oxford World’s Classic, The Adventures of Tom Sawyer (offer is limited while supply lasts).

The histories of Mark Twain, William Dean Howells and Harper’s Magazine are so intimately linked, so important to the fabric of the magazine, that I talk about Twain and Howells around the office as if they were still alive. The other day I told a staff meeting that as long as I was running Harper’s, it would remain a literary magazine that also publishes journalism — not the other way around — because of Howells’s and Twain’s ever-present legacy.

Howells met Twain in 1869, three years after Twain had published his first long narrative in Harper’s, “43 Days in an Open Boat.” As the future literary editor of Harper’s recalled, “At the time of our first meeting…Clemens (as I must call him instead of Mark Twain, which seemed always somehow to mask him from my personal sense) was wearing a sealskin coat, with the fur out, in the satisfaction of a caprice, or the love of strong effect which he was apt to indulge through life.” It’s no coincidence that for our special 150th anniversary issue in 2000, we constructed a cover photo of Twain in his dandy suit facing Tom Wolfe in his dandy suit.

Clemens and Howells became good friends and in 1875 the genius from Hannibal asked Howells to read the manuscript of The Adventures of Tom Sawyer. “I am glad to remember that I thoroughly liked The Adventures of Tom Sawyer,” Howells wrote, “and said so with every possible amplification. Very likely, I also made my suggestions for its improvement; I could not have been a real critic without that; and I have no doubt they were gratefully accepted and, I hope, never acted upon.” Howells was underrating his influence on Twain, who penned over 80 pieces for Harper’s. As a critic and a fine novelist in his own right, Howells was correct — Tom Sawyer is a great American novel. Indeed, not everyone agrees that it’s any less of an achievement than the more widely acclaimed (at least in serious literary circles) Huckleberry Finn. I’m looking forward to talking about the book next week and finding out the answer to a number of questions: for example, precisely how old is Tom Sawyer? I assume the Twain scholars in the audience will enlighten me on this and other matters.

What was your inspiration for Bad English?

What was your inspiration for Bad English?

What was your inspiration for choosing Middlemarch?

What was your inspiration for choosing Middlemarch? Where do you do your best writing? In airports.

Where do you do your best writing? In airports.