new posts in all blogs

Viewing: Blog Posts Tagged with: simon winchester, Most Recent at Top [Help]

Results 1 - 6 of 6

How to use this Page

You are viewing the most recent posts tagged with the words: simon winchester in the JacketFlap blog reader. What is a tag? Think of a tag as a keyword or category label. Tags can both help you find posts on JacketFlap.com as well as provide an easy way for you to "remember" and classify posts for later recall. Try adding a tag yourself by clicking "Add a tag" below a post's header. Scroll down through the list of Recent Posts in the left column and click on a post title that sounds interesting. You can view all posts from a specific blog by clicking the Blog name in the right column, or you can click a 'More Posts from this Blog' link in any individual post.

By: Alice,

on 8/31/2012

Blog:

OUPblog

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

Reference,

allison,

Dictionaries,

reflection,

definition,

Francine Prose,

Joshua Ferris,

thesaurus,

simon winchester,

Zadie Smith,

david foster wallace,

synonym,

katherine,

*Featured,

Lexicography & Language,

Allison Wright,

antonym,

Katherine Martin,

Oxford American Writer's Thesaurus,

lacerations,

inveigh,

jkucisvv2w,

dxmrwskbuhu,

0rnuz,

Add a tag

How do you choose the right word? Some just don’t fit what you’re trying to convey, either in the labor of love prose for your creative writing class, or the rogue auto-correct function on your phone.

Can you shed lacerations instead of tears? How is the word barren an attack on women? How do writers such as Joshua Ferris, Francine Prose, David Foster Wallace, Zadie Smith, and Simon Winchester weigh and inveigh against words?

We sat down with Katherine Martin and Allison Wright, editors of the Oxford American Writer’s Thesaurus, to discuss what makes a word distinctive from others and what writers can teach you about language.

Writing Today, the Choice of Words, and the Oxford American Writer’s Thesaurus

Click here to view the embedded video.

Reflections in the Oxford American Writer’s Thesaurus

Click here to view the embedded video.

The Use and Abuse of a Thesaurus

Click here to view the embedded video.

Katherine Martin is Head of US Dictionaries at Oxford University Press. Allison Wright is Editor, US Dictionaries at Oxford University Press.

Much more than a word list, the Oxford American Writer’s Thesaurus is a browsable source of inspiration as well as an authoritative guide to selecting and using vocabulary. This essential guide for writers provides real-life example sentences and a careful selection of the most relevant synonyms, as well as new usage notes, hints for choosing between similar words, a Word Finder section organized by subject, and a comprehensive language guide. The third edition revises and updates this innovative reference, adding hundreds of new words, senses, and phrases to its more than 300,000 synonyms and 10,000 antonyms. New features in this edition include over 200 literary and humorous quotations highlighting notable usages of words, and a revised graphical word toolkit feature showing common word combinations based on evidence in the Oxford Corpus. There is also a new introduction by noted language commentator Ben Zimmer.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only language, lexicography, word, etymology, and dictionary articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

View more about this book on the

By: Kirsty,

on 7/11/2011

Blog:

OUPblog

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

Literature,

Videos,

Oxford,

lewis carroll,

alice,

Alice in Wonderland,

Multimedia,

simon,

Prose,

simon winchester,

winchester,

wonderland,

*Featured,

alice liddell,

charles dodgson,

dodgson,

alice's day,

the alice behind wonderland,

yrrycimi6ls,

d2r2towrqcu,

Add a tag

This past weekend saw Oxford’s annual Alice’s Day take place, featuring lots of Alice in Wonderland themed events and exhibitions. With that in mind, today we bring you two videos of Simon Winchester talking about Charles Dodgson (AKA Lewis Carroll) and both his love of photography and his relationship with Alice Liddell and her family. You can read an excerpt from his book, The Alice Behind Wonderland, here.

Click here to view the embedded video.

Click here to view the embedded video.

Simon Winchester is the author of the bestselling books The Surgeon of Crowthorne, The Meaning of Everything, The Map that Changed the World, Krakatoa, Atlantic, and The Man Who Loved China. In recognition of his accomplished body of work, he was awarded the OBE in 2006. He lives in Massachusettes and in the Western Isles of Scotland.

View more about this book on the

By: Kirsty,

on 4/20/2011

Blog:

OUPblog

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

children,

Literature,

UK,

photography,

lewis carroll,

Alice in Wonderland,

Victorian,

Prose,

simon winchester,

*Featured,

Art & Architecture,

alice behind wonderland,

alice liddell,

alice murdoch,

charles dodgson,

dodgson,

Add a tag

On a summer’s day in 1858, in a garden behind Christ Church, Oxford, Charles Dodgson, AKA Lewis Carroll, photographed six-year-old Alice Liddell, the daughter of the college dean, with a Thomas Ottewill Registered Double Folding Camera, recently purchased in London. In The Alice Behind Wonderland, Simon Winchester uses the resulting image as the vehicle for a brief excursion behind the lens, a focal point on the origins of a classic work of literature. In the short excerpt from the book, below, Winchester writes about the pictures of children he took in the years before he photographed Alice Liddell.

Portraiture was what most interested Dodgson, and one assumes he began making images of people from the moment his skills had developed enough to allow him to assert his independence from [his friend and fellow photographer, Reginald] Southey. His first attempts have not survived—but principally, most scholars think, because he was not satisfied with their quality, and, being a fastidious man, a perfectionist, he wanted his art to be worthy of posterity. There are just two presumed self-portraits from this time—one showing him standing by a table and looking down, which is held today in a library in Surrey, the second in the same pose but looking up, which is in the Morgan Library in New York. Both are catalogued in Dodgson’s curiously blocky hand—and in his signature violet ink. They bear the numbers 15 and 16, suggesting there were many others that were either lost or discarded.

Once the long vacation of 1856 started, Dodgson was able to travel beyond Oxford, and he made the conscious decision to take along his camera, the folding darkroom and its chemicals, and all the other paraphernalia. There is some forensic suggestion—mainly from a paper trail of halfway reasonable portraits, some of his family and others of strangers—that he went first home, to Croft. But the most important photographs from this period were taken when he arrived in the second week of June to stay at the house of his paternal uncle Hassard Hume Dodgson, in Putney.

Like Dodgson’s maternal uncle Skeffington Lutwidge, Hassard Dodgson was a barrister, and the holder of another title of Victorian folderol—the Master of the Common Pleas. He was well connected and comfortably off, and lived in a mighty Victorian redbrick pile beside the Thames, Park Lodge. So Dodgson spent his two early summer weeks that year in an atmosphere of congenial relaxation, traveling occasionally into London to exhibits at the Royal Academy and the Society of Watercolourists, as well as visiting Sir Jonathan Pollock—to whom he would in time be distantly related by marriage. Pollock, who, in addition to being a council member of the newly constituted Photographical Society of London and a mathematician (a student of Fermat’s theorem), was at the time one of England’s leading judges, famous for his role in the interminable case of Wright v. Tatham, which many believe was the eight-year-long inspiration for Jarndyce v. Jarndyce in Dickens’s great novel Bleak House . Dodgson went to see this formidable personage for advice: he returned entirely convinced that portraiture was to be his métier.

During those two June weeks he worked his way with great deliberation and assiduity through the entire range of subjects who lived in or turned up at Uncle Hassard’s home. There was Hassard himself, then his wife, Caroline Hume, and an assortment of nephews and nieces and friends. Most of them were girls, whose names—Lucy, Laura, Charlotte, Amy, Katherine, and Millicent—far outnumbered those for boys.

One picture from that London interlude stands out: the one he took on the afternoon of June 19, 1856, of the four-year-old daughter of a senior civil servant who also served as the

By: Rebecca,

on 12/8/2009

Blog:

OUPblog

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

holiday,

A-Featured,

A-Editor's Picks,

Prose,

simon winchester,

Georges Perec,

09,

Life A User's Manual,

books,

Blogs,

Add a tag

It has become a holiday tradition on the OUPblog to ask our favorite people about their favorite books. This year we asked authors to participate (OUP authors and non-OUP authors). For the next two weeks we will be posting their responses which reflect a wide variety of tastes and interests, in fiction, non-fiction and children’s books. Check back daily for new books to add to your 2010 reading lists. If that isn’t enough to keep you busy next year check out all the great books we have discovered during past holiday seasons: 2006, 2007, 2008 (US), and 2008 (UK).

Today, to kick off our holiday book bonanza is author Simon Winchester. Winchester studied geology at Oxford and has written for Condé Nast Traveler, Smithsonian, and National Geographic. He is the author of A Crack in the Edge of the World, Krakatoa, The Map That Changed the World, The Professor and the Madman, The Fracture Zone, Outposts, Korea, among many other titles. He lives in Massachusetts and in the Western Isles of Scotland.

I am a printer, a weekend amateur, and for good rollicking fun I spend a great deal of time setting type by hand. It is a contemplative calling that, among other things, offers very visible proof of many eternal verities about our language – one of the most obvious being what we all know to be true, but rarely think about: that the letter ‘e’ is by far the most common in the making of our words.

There it sits in the job-case – a great box of little lead ‘e’s, front and center, far outstripping in number and volume any of the other twenty-five letters, and placed in the case just so, because your hand will reach into that particular box time and time again as you set your copy in the composing stick.

It is difficult to think of writing without such a symbol to hand (though that last sentence happens not to sport a single ‘e’). It can be an amusing diversion of time – and a good way of falling asleep, if you can’t – to try to recast famous lines from l

By: Kirsty,

on 10/15/2008

Blog:

OUPblog

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

john simpson,

History,

Reference,

UK,

Current Events,

A-Featured,

Lexicography,

Dictionaries,

Online Resources,

oed,

oxford english dictionary,

ammon shea,

Samuel Johnson,

simon winchester,

Add a tag

By Kirsty McHugh, OUP UK

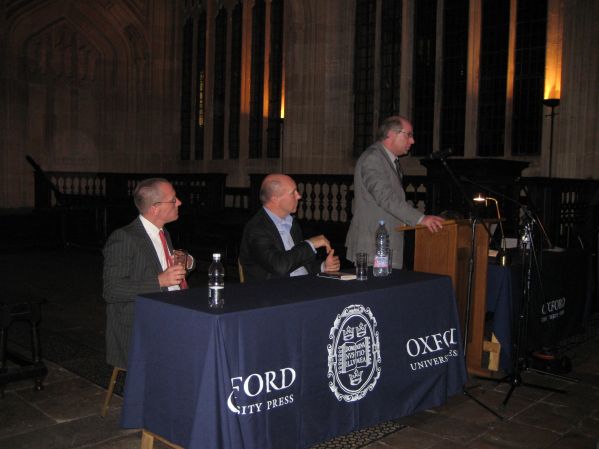

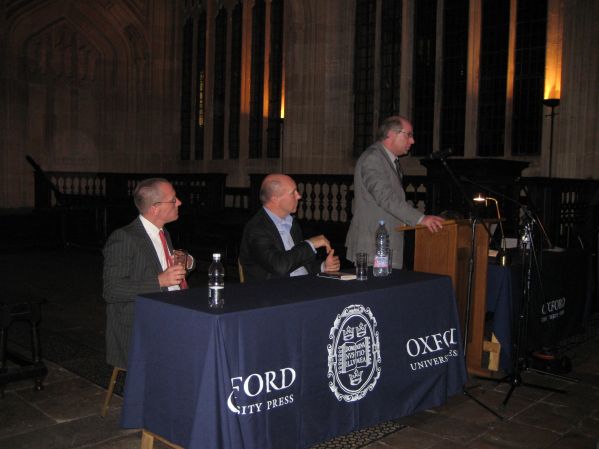

Last night saw the OED 80th Anniversary celebrations culminate in a public panel discussion on  ‘The Oxford English Dictionary: Past, Present, and Future’ at the incredibly beautiful and historic Bodleian Library in Oxford.

‘The Oxford English Dictionary: Past, Present, and Future’ at the incredibly beautiful and historic Bodleian Library in Oxford.

On the panel was OED chief editor John Simpson, historian and author of The Meaning of Everything: The Story of the Oxford English Dictionary Simon Winchester, and Ammon Shea, who wrote Reading the OED and who of course needs no introduction to OUPblog readers.

Simon Winchester opened up proceedings with a history of dictionaries, telling us that 1604 saw the first modern  dictionary as we understand them today. In that case, it was a slim book written by Robert Cawdrey called A table alphabeticall conteyning and teaching the true writing, and vnderstanding of hard vsuall English wordes, borrowed from the Hebrew, Greeke, Latine, or French, &c. With the interpretation thereof by plaine English words, gathered for the benefit & helpe of ladies, gentlewomen, or any other vnskilfull persons. Whereby they may the more easilie and better vnderstand many hard English wordes, vvhich they shall heare or read in scriptures, sermons, or elswhere, and also be made able to vse the same aptly themselues. Snappy, huh?

dictionary as we understand them today. In that case, it was a slim book written by Robert Cawdrey called A table alphabeticall conteyning and teaching the true writing, and vnderstanding of hard vsuall English wordes, borrowed from the Hebrew, Greeke, Latine, or French, &c. With the interpretation thereof by plaine English words, gathered for the benefit & helpe of ladies, gentlewomen, or any other vnskilfull persons. Whereby they may the more easilie and better vnderstand many hard English wordes, vvhich they shall heare or read in scriptures, sermons, or elswhere, and also be made able to vse the same aptly themselues. Snappy, huh?

He then went on to talk about arguably the most famous dictionary (other than the OED obviously!): that by Samuel Johnson. Johnson was known as a bit of a cantankerous fellow, and this sometimes filtered down into his definitions. For example, his famous definition of ‘oats’:

A grain, which in England is generally given to horses, but in Scotland appears to support the people.

I won’t take offence, promise. Then we heard about the famous OED editors of the late 19th and early 20th century: Herbert Coleridge, Frederick Furnivall (who had to leave the job after it was realised that he was more interested in sculling and well-endowed young ladies), and, of course, James Murray.

John Simpson, today’s OED editor, took us through what happens to an entry and the kinds of information that is needed for the Dictionary. He used the example of ‘lifeboat’ and took us through its history from its first appearance in the first edition of the OED , to moving from being hyphenated (life-boat) to a solid word in 1903, up to the latest evidence of its earliest usage, which will be in the updated entry to go online soon.

Then, to finish the evening, Ammon Shea told us all about reading the OED from A-Z in one year. To read more about the many wonderful words he discovered during that year, then do read his past posts for OUPblog. But I couldn’t agree with him more when he said that there is much emotional content within the Oxford English Dictionary: the poignancy of a word that means ‘to no longer own something, but to wish that you still did’, or a word that means ‘the sound of leaves rustling in the wind’. The OED is, as Ammon said, a “remarkable creature of literature”, which is why I am so happy to have been here for the 80th anniversary celebrations.

Here’s to another 80 years, and many, many more.

ShareThis

First, an announcement. Things Mean a Lot is hosting the next Bookworm's Carnival. The theme is fairy tales, so you know I'm all over that. Submission deadline is June 13. Info is here.

This weekend is the 48 Hour Challenge, so I'll be blogging up an over-caffeinated storm. I'm going for the gold.

Also, I get to turn my air-conditioning on this weekend. We try to go as long as possible, but given we're currently in a "heat advisory" and tomorrow's heat index is supposed to be 110? Well, that's why we HAVE a/c, right? Right.

Now, a story. Then a review.

One of the cool things about going to a small liberal arts college with no grad students is the academic stuff they let you get away with. Seriously. End of junior year, my friend Ellie and I decided we wanted to take a class together in the fall. But, she was a physics major and I was history and Chinese... so we designed an independent study that combined all 3 of these things. Yes, our 2 credit class was on Ancient Chinese Astronomy. We even conned a professor into advising us on this!

In the end, it kinda sucked. I had way too much on my plate that semester, and we had an issue with sources. When we put together our bibliography as part of the class proposal, it was long and extensive. But, when class started, we realized we really only had 1 source: Joseph Needham's Science and Civilisation in China. Everything else was just a rehash of Needham's works. Some had better photographs, but usually it was just a simplification or further proof that Needham was right. It all came down to Needham. And given that our library had a complete set of Needham? That's what we read. (Also the Needham? Takes up multiple shelves. It's pretty intense.)

You can understand why I jumped all over

The Man Who Loved China: The Fantastic Story of the Eccentric Scientist Who Unlocked the Mysteries of the Middle Kingdom Simon Winchester

Joseph Needham was a brilliant bio-chemist, a socialist, a Morris Dancer, and he definitely liked the ladies. After falling hopelessly in love with Lu Gwei-djen (who was not a wife, but as theirs was an open marriage, it didn't cause nearly the drama you would expect) he also became a devote Sinophile.

During WWII, he went to Chongqing (where the capital had retreated) as British diplomat--his job was to get Chinese universities the equipment they needed to continue to function. While there, he started his research into how China was the first to discover such things as printing, gun powder, the compass, and paper. That China was the first is common knowledge NOW, but only because of Needham.

A fascinating story, plus it's by Winchester. I've always meant to read his books, but this is the first I actually did. It's completely accessible and engaging. Winchester can certainly tell a story. What I most admire is his ability to make the finer points of history and culture easy to understand without losing any of the accuracy. I often see in mainstream history or children's nonfiction a simplification to the point of no longer being entirely accurate. This is not the case with Winchester's works.

I highly recommend it, and will be giving a copy to Ellie when she visits next weekend.

![]()

Well, I liked your idea of inventing your own course! And in the long run, perhaps you learned more about how sometimes it's easier to take what comes, rather than circumvent the system...

As you are a Chinese major who just finished the Needham book, I'd like to recommend Return to Middle Kingdom by Yuan-tsung Chen. It's as engrossing as reading a historical novel, and is really great for anyone who wants to understand the origin of modern China.