new posts in all blogs

Viewing: Blog Posts Tagged with: oxford english dictionary, Most Recent at Top [Help]

Results 1 - 25 of 56

How to use this Page

You are viewing the most recent posts tagged with the words: oxford english dictionary in the JacketFlap blog reader. What is a tag? Think of a tag as a keyword or category label. Tags can both help you find posts on JacketFlap.com as well as provide an easy way for you to "remember" and classify posts for later recall. Try adding a tag yourself by clicking "Add a tag" below a post's header. Scroll down through the list of Recent Posts in the left column and click on a post title that sounds interesting. You can view all posts from a specific blog by clicking the Blog name in the right column, or you can click a 'More Posts from this Blog' link in any individual post.

By: Carolyn Napolitano,

on 10/20/2016

Blog:

OUPblog

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

Books,

Literature,

Language,

q&a,

fish,

Oxford University Press,

oed,

oxford english dictionary,

etymology,

British,

Linguistics,

lexicographer,

*Featured,

oxford dictionaries,

Peter Gilliver,

Dictionaries & Lexicography,

au naturel,

aumoniere,

chalazion,

The Making of the Oxford English Dictionary,

twiffler,

Add a tag

Peter Gilliver has been an editor of the Oxford English Dictionary since 1987, and is now one of the Dictionary's most experienced lexicographers; he has also contributed to several other dictionaries published by OUP. In addition to his lexicographical work, he has been writing and speaking about the history of the OED for over fifteen years. In this two part Q&A, we learn more about how his passion for lexicography inspired him.

The post Learning about lexicography: A Q&A with Peter Gilliver part 1 appeared first on OUPblog.

By: Cassandra Gill,

on 10/9/2016

Blog:

OUPblog

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

History,

Politics,

Language,

Social Networking,

social media,

America,

oxford english dictionary,

enlightenment,

twitter,

Tweets,

english language,

*Featured,

presidential candidates,

american politics,

Online products,

digital technology,

public officials,

The Independent Reflector,

William Livingston,

Add a tag

A New Yorker once declared that “Twitter” had “struck Terror into a whole Hierarchy.” He had no computer, no cellphone, and no online social media following. He was not a presidential candidate, but he would go on to sign the Constitution of the United States. So who was he? And what did he mean by “Twitter”?

The post Twitter and the Enlightenment in early America appeared first on OUPblog.

By: Carolyn Napolitano,

on 9/2/2016

Blog:

OUPblog

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

Books,

chocolate,

Oxford,

Language,

oxford english dictionary,

British,

Braille,

Linguistics,

cambridge,

*Featured,

james murray,

esperanto,

OxfordWords blog,

Peter Gilliver,

Scriptorium,

Dictionaries & Lexicography,

Arthur Maling,

biplane,

Charles Onions,

The Making of the OED,

Add a tag

The Oxford English Dictionary is the work of people: many thousands of them. In my work on the history of the Dictionary I have found the stories of many of those people endlessly fascinating. Very often an individual will enter the story who cries out to be made the subject of a biography in his or her own right; others, while not quite fascinating enough for that, are still sufficiently interesting that they could be a dangerous distraction to me when I was trying to concentrate on the main task of telling the story of the project itself.

The post Esperanto, chocolate, and biplanes in Braille: the interests of Arthur Maling appeared first on OUPblog.

By: Estefania Ospina,

on 9/1/2016

Blog:

OUPblog

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

oxford english dictionary,

etymology,

Linguistics,

Exotic,

The Oxford Comment,

*Featured,

Audio & Podcasts,

Theatre & Dance,

Online products,

Arts & Humanities,

The Naked Result,

commodities,

exotic dancing,

luxury items,

Luxury: A Rich History,

Redeeming Kamasutra,

Western world,

Books,

History,

Literature,

Language,

India,

Add a tag

The word “exotic” can take on various different meanings and connotations, depending on how it is used. It can serve as an adjective or a noun, to describe a commodity, a person, or even a human activity. No matter its usage, however, the underlying perception is that is refers to something foreign or unknown, a function which can vary greatly in unison with other words, from enriching the luxury status of commodities, to fully sexualizing a literary work of psychology and anthropology, such as the Kamasutra.

In this episode of the Oxford Comment, we sat down with Eleanor Maier, Senior Editor at the Oxford English Dictionary, Giorgio Riello, co-author of Luxury: A Rich History, Wendy Doniger, author of Redeeimg the Kamasutra, Jessica Berson, author of The Naked Result: How Exotic Dance Became Big Business, and Rachel Kuo, contributing writer at everydayfeminism.com, to learn more about the history and usage of the word.

The post Exotic – Episode 38 – The Oxford Comment appeared first on OUPblog.

By: Catherine,

on 4/23/2016

Blog:

OUPblog

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

shambles,

West Germanic,

History,

Language,

chaos,

word origins,

oed,

oxford english dictionary,

etymology,

Linguistics,

Old English,

modern english,

*Featured,

oxford dictionaries,

OxfordWords blog,

Dictionaries & Lexicography,

Add a tag

You just lost your job. Your partner broke up with you. You’re late on rent. Then, you dropped your iPhone in the toilet. “My life’s in shambles!” you shout. Had you so exclaimed, say, in an Anglo-Saxon village over 1,000 years ago, your fellow Old English speakers may have given you a puzzled look. “Your life’s in footstools?” they’d ask. “And what’s an iPhone?”

The post The shambolic life of ‘shambles’ appeared first on OUPblog.

By: Carolyn Napolitano,

on 4/10/2016

Blog:

OUPblog

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

Dictionaries & Lexicography,

Edwin Battistella,

Sorry About That,

Between the Lines with Edwin Battistella,

The Language of Public Apology,

Alfred Hart,

Buffy the Vampire Slayer<,

Measure for Measure,

Neology,

Shakespeare and new words,

Books,

Literature,

shakespeare,

Language,

oed,

oxford english dictionary,

Linguistics,

a midsummer night's dream,

*Featured,

Add a tag

William Shakespeare died four hundred years ago this month and my local library is celebrating the anniversary. It sounds a bit macabre when you put it that way, of course, so they are billing it as a celebration of Shakespeare’s legacy. I took this celebratory occasion to talk with my students about Shakespeare’s linguistic legacy.

The post Shakespeare’s linguistic legacy appeared first on OUPblog.

By: Catherine,

on 4/9/2016

Blog:

OUPblog

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

oed,

oxford english dictionary,

timeline,

english language,

*Featured,

oxford dictionaries,

English Words,

OxfordWords blog,

Dictionaries & Lexicography,

Quizzes & Polls,

history of words,

History,

Language,

Add a tag

Do you know when laugh entered the English language? What about cricket or fair-weather friend? Take the OED Timeline Challenge and find out if you are a lexical brainiac (1975). To play, simply drag the word to the date at which you think it entered the English language.

The post OED timeline challenge: Can you guess when these words entered the English language? appeared first on OUPblog.

By: Catherine,

on 3/26/2016

Blog:

OUPblog

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

Politics,

Language,

Media,

Barack Obama,

terrorism,

oxford english dictionary,

criminal,

*Featured,

oxford dictionaries,

mastermind,

ringleader,

Charlotte Buxton,

OxfordWords blog,

Dictionaries & Lexicography,

The Eustace Diamonds. anthony trollope,

Add a tag

In a speech made after the November terrorist attacks in Paris, President Obama criticized the media’s use of the word mastermind to describe Abdelhamid Abaaoud. “He’s not a mastermind,” he stated. “He found a few other vicious people, got hands on some fairly conventional weapons, and sadly, it turns out that if you’re willing to die you can kill a lot of people.”

The post Word in the news: Mastermind appeared first on OUPblog.

By: Alice,

on 1/25/2016

Blog:

OUPblog

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

Books,

Language,

oxford english dictionary,

Linguistics,

mate,

*Featured,

Australian English,

Bruce Moore,

History of Australian Words,

What's Their Story?,

Australian National Dictionary,

Add a tag

Mate is one of those words that is used widely in Englishes other than Australian English, and yet has a special resonance in Australia. Although it had a very detailed entry in the first edition of the Oxford English Dictionary (the letter M was completed 1904–8), the Australian National Dictionary (AND) included mate in its first edition of 1988, thus marking it as an Australianism.

The post ‘Mate’ in Australian English appeared first on OUPblog.

By: SoniaT,

on 12/9/2015

Blog:

OUPblog

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

Books,

Oxford Etymologist,

oed,

oxford english dictionary,

anatoly liberman,

Linguistics,

*Featured,

Early English Etymology,

Dictionaries & Lexicography,

Word Origins And How We Know Them,

The Oxford Etymologist,

An Analytic Dictionary of English Etymology: An Introduction,

Anatoly Liberman Column,

Blunt in Ormulum,

Bluntisaham,

Definition of Blunt,

Etymology for Everyone,

Etymology of Blunt,

Word Origins of Blunt,

Word With Unknown Origins,

Words with Family Name Origins,

Add a tag

Yes, you understood the title and identified its source correctly: this pseudo-Shakespearean post is meant to keep you interested in the blog “The Oxford Etymologist” and to offer some new ideas on the origin of the highlighted adjective.

The post To whet your almost BLUNTED purpose…Part 1 appeared first on OUPblog.

By: SoniaT,

on 12/3/2015

Blog:

OUPblog

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

The Oxford Comment,

*Featured,

allan metcalf,

Oxford Dictionaries Online,

ODO,

Online products,

Dictionaries & Lexicography,

Oxford University Press Podcast,

From Skedaddle to Selfie,

Christmas Idioms,

Etymology of Christmas,

Holiday Sayings,

How to Spell Chanukah,

Language of the Holidays,

Words of the Generations,

Books,

oed,

oxford english dictionary,

Linguistics,

Add a tag

Say goodbye to endless stuffing: it's time to welcome our most beloved season of wreaths, wrapping paper...and confusion. The questions, as we began delving, were endless. Should we say happy holidays or season's greetings?

The post Season’s greetings – Episode 29 – The Oxford Comment appeared first on OUPblog.

By: SoniaT,

on 9/23/2015

Blog:

OUPblog

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

Books,

Oxford Etymologist,

word origins,

oed,

oxford english dictionary,

anatoly liberman,

Linguistics,

Editor's Picks,

*Featured,

Dictionaries & Lexicography,

Word Origins And How We Know Them,

Celtic etymology,

derivations of baddare,

Elof Hellquist,

etymological dictionary of Swedish,

etymology of baddare,

Frederik A. Tamm,

Scandinavian etymology,

Swedish vocabulary,

Word Etymology,

Add a tag

Not too long ago, I promised to return to the origin of b-d words. Today I’ll deal with Engl. bad and its look-alikes, possibly for the last time—not because everything is now clear (nothing is clear), but because I have said all I could, and even this post originated as an answer to the remarks by our correspondents John Larsson (Denmark) and Olivier van Renswoude (the Netherlands).

The post The B-word and its kin appeared first on OUPblog.

By: SoniaT,

on 9/16/2015

Blog:

OUPblog

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

Books,

apropos whipping the cat,

Common Phrases,

cool as a cucumber,

cut the mustard,

English Etymology,

in the house,

phrase origins,

the word buggy,

Oxford Etymologist,

word origins,

oed,

oxford english dictionary,

anatoly liberman,

Linguistics,

Editor's Picks,

*Featured,

Dictionaries & Lexicography,

Word Origins And How We Know Them,

Add a tag

What is the origin of the now popular phrase in the house, as in “Ladies and gentlemen, Bobby Brown is in the house”? I don’t know, but a short explanation should be added to my response. A good deal depends on the meaning of the question “What is the origin of a certain phrase?” If the querist wonders when the phrase surfaced in writing, the date, given our resources, is usually ascertainable.

The post Wading through an endless field, or, still gleaning appeared first on OUPblog.

By: Carolyn Napolitano,

on 7/12/2015

Blog:

OUPblog

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

Books,

America,

oxford english dictionary,

Linguistics,

*Featured,

Edwin Battistella,

Sorry About That: The Language of Public Apology,

American revolution synonyms,

fourth of July terms,

language of declaration of independence,

language of politics,

language of rebellion,

language of revolutionary war,

political rebellion words,

words of Revolutionary war,

Add a tag

Amid Fourth of July parades and fireworks, I found myself asking this: why do we call this day 'Independence Day' rather than 'Revolution Day?' The short answer,of course, is that on 4 July, we celebrate the signing of the Declaration of Independence, a day that has been commemorated since 1777.

The post Talkin’ about a ‘Revolution’ appeared first on OUPblog.

The Oxford English Dictionary (OED) has announced the addition of approximately 500 new words. Some of the newly added words include twerk, cisgender, FLOTUS, jeggings, and totes.

The Oxford English Dictionary (OED) has announced the addition of approximately 500 new words. Some of the newly added words include twerk, cisgender, FLOTUS, jeggings, and totes.

Click on this link to check out the full list of new words. Katherine Connor Martin, the head of the United States Dictionaries, wrote an article about the newly added words.

Here’s an excerpt from Martin’s piece focusing on the word twerk: ”

The use of twerk to describe a type of dancing which emphasizes the performer’s posterior originated in the early 1990s in the New Orleans ‘bounce’ music scene, but the word itself seems to have its origins more than 170 years before. It was in use in English as a noun by 1820 (originally spelled ‘twirk’), referring to ‘a twisting or jerking movement; a twitch’: ‘Really the Germans do allow themselves such twists & twirks of the pen, that it would puzzle any one’ (Charles Clairmont, Letter, 26 Feb. 1820). Verbal use is first attested just a few decades later, and the ‘twerk’ spelling had come about by 1901. The precise origin of the word is uncertain, but it may be a blend of twist or twitch and jerk, with influence from quirk n.1 at the noun and from work v. in reference to the dance.

(via The Independent)

By: SoniaT,

on 6/27/2015

Blog:

OUPblog

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

oed,

oxford english dictionary,

*Featured,

oxford dictionaries,

Katherine Connor Martin,

OED Update,

twerk dictionary meaning,

twerk etymology,

twerk meaning,

twerk word origins,

twerk word usage,

twerking etymology,

twerking meaning,

Add a tag

When the word twerk burst into the global vocabulary of English a few years ago with reference to a dance involving thrusting movements of the bottom and hips, most accounts of its origin pointed in the same direction, to the New Orleans ‘bounce’ music scene of the 1990s, and in particular to a 1993 recording by DJ Jubilee, ‘Jubilee All’, whose refrain exhorted dancers to ‘twerk, baby, twerk’. However, information in a new entry published in the historical Oxford English Dictionary this month, as part of the June 2015 update, reveals that the word was in fact present in English more than 170 years earlier.

The post Twerking since 1820: an OED antedating appeared first on OUPblog.

By: SoniaT,

on 5/9/2015

Blog:

OUPblog

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

*Featured,

jeremy marshall,

oxford dictionaries,

oxford words,

Online products,

OxfordWords blog,

Earth & Life Sciences,

definition of evolution,

etymology of evolution,

meaning of evolution,

oxford english dictionary,

Linguistics,

Add a tag

It is curious that, although the modern theory of evolution has its source in Charles Darwin’s great book On the Origin of Species (1859), the word evolution does not appear in the original text at all. In fact, Darwin seems deliberately to have avoided using the word evolution, preferring to refer to the process of biological change as ‘transmutation’. Some of the reasons for this, and for continuing confusion about the word evolution in the succeeding century and a half, can be unpacked from the word’s entry in the Oxford English Dictionary (OED).

The post The evolution of the word ‘evolution’ appeared first on OUPblog.

By: Julia Callaway,

on 11/26/2014

Blog:

OUPblog

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

Books,

grammar,

Language,

Oxford Etymologist,

word origins,

spelling,

oed,

oxford english dictionary,

etymology,

anatoly liberman,

monthly gleanings,

*Featured,

james murray,

Dictionaries & Lexicography,

John Vanbrugh,

Word Origins And How We Know Them,

Add a tag

As always, I want to thank those who have commented on the posts and written me letters bypassing the “official channels” (though nothing can be more in- or unofficial than this blog; I distinguish between inofficial and unofficial, to the disapproval of the spellchecker and some editors). I only wish there were more comments and letters. With regard to my “bimonthly” gleanings, I did think of calling them bimestrial but decided that even with my propensity for hard words I could not afford such a monster. Trimestrial and quarterly are another matter. By the way, I would not call fortnightly a quaint Briticism. The noun fortnight is indeed unknown in the United States, but anyone who reads books by British authors will recognize it. It is sennight “seven nights; a week,” as opposed to “fourteen nights; two weeks,” that is truly dead, except to Walter Scott’s few remaining admirers.

The comments on livid were quite helpful, so that perhaps livid with rage does mean “white.” I was also delighted to see Stephen Goranson’s antedating of hully gully. Unfortunately, I do not know this word’s etymology and have little chance of ever discovering it, but I will risk repeating my tentative idea. Wherever the name of this game was coined, it seems to have been “Anglicized,” and in English reduplicating compounds of the Humpty Dumpty, humdrum, and helter-skelter type, those in which the first element begins with an h, the determining part is usually the second, while the first is added for the sake of rhyme. If this rule works for hully gully, the clue to the word’s origin is hidden in gully, with a possible reference to a dupe, a gull, a gullible person; hully is, figuratively speaking, an empty nut. A mere guess, to repeat once again Walter Skeat’s favorite phrase.

The future of spelling reform and realpolitik

Some time ago I promised to return to this theme, and now that the year (one more year!) is coming to an end, I would like to make good on my promise. There would have been no need to keep beating this moribund horse but for a rejoinder by Mr. Steve Bett to my modest proposal for simplifying English spelling. I am afraid that the reformers of our generation won’t be more successful than those who wrote pleading letters to journals in the thirties of the nineteenth century. Perhaps the Congress being planned by the Society will succeed in making powerful elites on both sides of the Atlantic interested in the sorry plight of English spellers. I wish it luck, and in the meantime will touch briefly on the discussion within the Society.

In the past, minimal reformers, Mr. Bett asserts, usually failed to implement the first step. The first step is not an issue as long as we agree that there should be one. Any improvement will be beneficial, for example, doing away with some useless double letters (till ~ until); regularizing doublets like speak ~ speech; abolishing c in scion, scene, scepter ~ scepter, and, less obviously, scent; substituting sk for sc in scathe, scavenger, and the like (by the way, in the United States, skeptic is the norm); accepting (akcepting?) the verbal suffix -ize for -ise and of -or for -our throughout — I can go on and on, but the question is not where to begin but whether we want a gradual or a one-fell-swoop reform. Although I am ready to begin anywhere, I am an advocate of painless medicine and don’t believe in the success of hav, liv, and giv, however silly the present norm may be (those words are too frequent to be tampered with), while til and unskathed will probably meet with little resistance.

I am familiar with several excellent proposals of what may be called phonetic spelling. No one, Mr. Bett assures me, advocates phonetic spelling. “What about phonemic spelling?” he asks. This is mere quibbling. Some dialectologists, especially in Norway, used an extremely elaborate transcription for rendering the pronunciation of their subjects. To read it is a torture. Of course, no one advocates such a system. Speakers deal with phonemes rather than “sounds.” But Mr. Bett writes bás Róman alfàbet shud rèmán ùnchánjd for “base Roman alphabet should remain unchanged.” I am all for alfabet (ph is a nuisance) and with some reservations for shud, but the rest is, in my opinion, untenable. It matters little whether this system is clever, convenient, or easy to remember. If we offer it to the public, we’ll be laughed out of court.

Mr. Bett indicates that publishers are reluctant to introduce changes and that lexicographers are not interested in becoming the standard bearers of the reform. He is right. That is why it is necessary to find a body (The Board of Education? Parliament? Congress?) that has the authority to impose changes. I have made this point many times and hope that the projected Congress will not come away empty-handed. We will fail without influential sponsors, but first of all, the Society needs an agenda, agree to the basic principles of a program, and for at least some time refrain from infighting.

The indefinite pronoun one once again

I was asked whether I am uncomfortable with phrases like to keep oneself to oneself. No, I am not, and I don’t object to the sentence one should mind one’s own business. A colleague of mine has observed that the French and the Germans, with their on and man are better off than those who grapple with one in English. No doubt about it. All this is especially irritating because the indefinite pronoun one seems to owe its existence to French on. However, on and man, can function only as the subject of the sentence. Nothing in the world is perfect.

Our dance around pronouns sometimes assumes grotesque dimensions. In an email, a student informed me that her cousin is sick and she has to take care of them. She does not know, she added, when they will be well enough, to allow her to attend classes. Not that I am inordinately curious, but it is funny that I was protected from knowing whether “they” are a man or a woman. In my archive, I have only one similar example (I quoted it long ago): “If John calls, tell them I’ll soon be back.” Being brainwashed may have unexpected consequences.

Earl and the Herulians

Our faithful correspondent Mr. John Larsson wrote me a letter about the word earl. I have a good deal to say about it. But if he has access to the excellent but now defunct periodical General Linguistics, he will find all he needs in the article on the Herulians and earls by Marvin Taylor in Volume 30 for 1992 (the article begins on p. 109).

The OED: Behind the scenes

Many people realize what a gigantic effort it took to produce the Oxford English Dictionary, but only insiders are aware of how hard it is to do what seems trivial to a non-specialist. Next year we’ll mark the centennial of James A. H. Murray’s death, and I hope that this anniversary will not be ignored the way Skeat’s centennial was in 2012. Today I will cite one example of the OED’s labors in the early stages of work on it. In 1866, Cornelius Payne, Jun. was reading John Vanbrugh’s plays for the projected dictionary, and in Notes and Queries, Series 3, No. X for July 7 he asked the readers to explain several passages he did not understand. Two of them follow. 1) Clarissa: “I wish he would quarrel with me to-day a little, to pass away the time.” Flippanta: “Why, if you please to drop yourself in his way, six to four but he scolds one Rubbers with you.” 2) Sir Francis:…here, John Moody, get us a tankard of good hearty stuff presently. J. Moody: Sir, here’s Norfolk-nog to be had at next door.” Rubber(s) is a well-known card term, and it also means “quarrel.” See rubber, the end of the entry. Norfolk-nog did not make its way into the dictionary because no idiomatic sense is attached to it: the phrase means “nog made and served in Norfolk” (however, the OED did not neglect Norfolk). Such was and still is the price of every step. Read and wonder. And if you have a taste for Restoration drama, read Vanbrugh’s plays: moderately enjoyable but not always fit for the most innocent children (like those surrounding us today).

The post Monthly etymology gleanings for November 2014 appeared first on OUPblog.

By: Julia Callaway,

on 4/19/2014

Blog:

OUPblog

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

Language,

oxford english dictionary,

henry james,

*Featured,

oxford dictionaries,

oxfordwords blog,

Dictionaries & Lexicography,

Jeff Sherwood,

very idiosyncrasy,

intersection between registers and,

phrase green,

and modernist,

its protagonist is,

Add a tag

By Jeff Sherwood

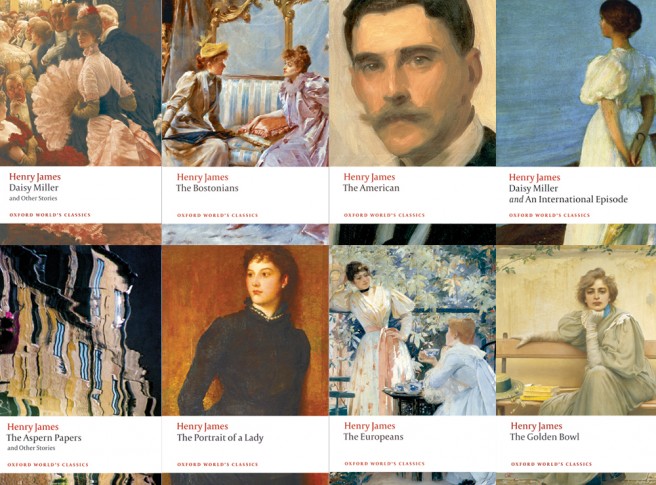

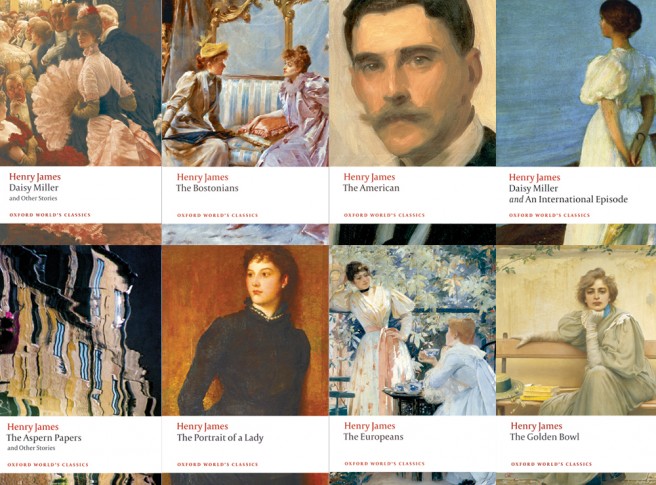

It is virtually impossible for an English-language lexicographer to ignore the long shadow cast by Henry James, that late nineteenth-century writer of fiction, criticism, and travelogues. We can attribute this in the first place to the sheer cosmopolitanism of his prose. James’s writing marks the point of intersection between registers and regions of English that we typically think of as mutually opposed: American and British, Victorian and modernist, intellectual and popular, even the simple good sense of Saxon-Germanicism and the fine silk shades of Franco-Romanticism. Thus, because his writing defies easy categories, it isn’t hard to suppose that James belongs in the back parlor of English-language history, a curiosity of passing interest, but one which, in its very idiosyncrasy, fails to capture the ‘ordinary, everyday’ language.

Henry James in the OED

Nevertheless, the Oxford English Dictionary (OED) cites Henry James over one thousand times, often in entries for common English words like use, turn, come, do, and be. At least one explanation for this preponderance is the fact that, precisely because James’s prose incorporates elements from so many different kinds of English, it is uniquely positioned to exemplify—and even differentiate between—very subtle distinctions of usage and meaning. Thus, at green adj. James’s early novel The American provides a downright crystalline use of the phrase green in earth to mean ‘just buried’: ‘He thought of Valentin de Bellegarde, still green in the earth of his burial.’ By adding the final (semantically superfluous) three words, not only does James clarify the phrase’s context, he accentuates its poetic wordplay; its dependence on the double sense of green both as ‘new’ (sense 7a) and as ‘covered with vegetation’ (sense 2a) in order to conjure the renewal of the earth that is part and parcel of the burial rite. In this case, poeticism, often an obstacle to meaning, is actually the most probable explanation for the collocation’s longevity.

This old thing?

James’s ability to write prose that is both fastidiously discerning and euphemistically elliptical is not accidental, and cannot fail to intrigue someone whose business it is to describe words all day. In fact, despite clearly affectionate attachments to a number of words (presence and relation leap to mind), the one I would nominate as James’s absolute favorite is of great concern for lexicography—the thoroughly common word thing. Meaning quite literally any-thing from the genitals (sense 11 c) to a work of art (sense 13, complete with a James citation), thing is remarkably Jamesian in its ability to denote both the most concretely literal elements of reality and the most rarefied abstractions of human thought. And it is in just this respect that the word presents itself at the heart of perhaps the most naïve yet essential question that the lexicographer must answer: whether any particular meaning associated with a given word is actually ‘a thing.’ At times, this can be quite easy: it is not difficult to evaluate whether the physical object we mean when we say ‘smart phone’ is a ‘thing.’ But in many cases, the ‘thing’ referred to by a word is only conceptual. The existence of what we mean by ‘freedom’, for example, cannot be empirically proven. All we can say for sure is that the frequency and manner in which people use such words strongly suggests that they mean specific ‘things’.

Philosophically speaking, what makes ‘thing’ so interesting is that it straddles the gap between words that refer to physical objects and those that refer to abstract concepts, serving as a kind of verbal ‘junk drawer’ where items from both groups get casually tossed, only to wind up completely tangled and confused. Unsurprisingly, this confusion is just what James chooses to explore in his short story ‘The Real Thing.’ Its protagonist is an illustrator visited by two aristocrats, Major and Mrs. Monarch, who have fallen on hard times. They volunteer themselves as models for the artist, presuming that as bona fide members of society they are more suitable subjects for the aristocratic characters he depicts than the working-class types he typically employs. In fact, of course, the couple is awkward and unnatural, unable to embody the concept of aristocracy despite being literal examples of it.

Defining the tooth fairy

In just the same way, when a particular word is used ‘in the real world’, it will almost never be a perfect example of the concept it refers to. Consequently, it becomes the lexicographer’s job to improve upon ‘the real thing’, to illustrate a word more vividly than the real world can. This is especially clear when the word being defined refers to a fictional character, like the tooth fairy. To give wholesale priority to this term as a lexical object would render a definition like ‘a fairy that takes children’s baby teeth after they fall out and leaves a coin under the child’s pillow.’ This covers how the term is ordinarily used, since in everyday speech we are not in the habit of constantly remarking on the key conceptual detail that the tooth fairy is not real. Nevertheless, a definition that fails to note this misses, paradoxically enough, ‘the real thing.’ Just as Major Monarch doesn’t quite look like ‘the real thing’ he is, sometimes a word used in everyday speech doesn’t quite capture the thing it really is.

Jeff Sherwood is a US Assistant Editor for Oxford Dictionaries. Read more about Henry James with Oxford World’s Classics. A version of this article originally appeared on the OxfordWords blog.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only language articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Image: Montage of Henry James Oxford World’s Classics editions.

The post Henry James, or, on the business of being a thing appeared first on OUPblog.

By: Alice,

on 4/9/2014

Blog:

OUPblog

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

bradley’s,

Books,

Language,

Oxford Etymologist,

oed,

etymology,

anatoly liberman,

*Featured,

Dictionaries & Lexicography,

Henry Bradley,

word origins,

oxford english dictionary,

bradley,

Add a tag

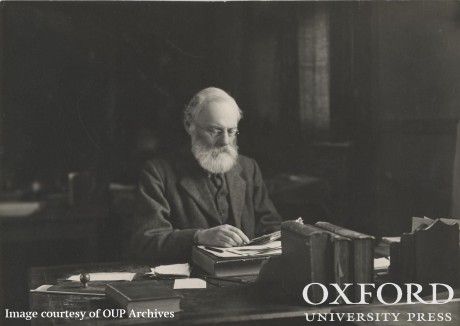

By Anatoly Liberman

At one time I intended to write a series of posts about the scholars who made significant contributions to English etymology but whose names are little known to the general public. Not that any etymologists can vie with politicians, actors, or athletes when it comes to funding and fame, but some of them wrote books and dictionaries and for a while stayed in the public eye. Ernest Weekley authored not only an etymological dictionary (a full and a concise version) but also multiple books on English words that were read and praised widely in the twenties and thirties of the twentieth century. Walter Skeat dominated the etymological scene for decades, and his “Concise Dictionary” graced many a desk on both sides of the Atlantic. James Murray attained glory as the editor of the Oxford English Dictionary. (Curiously, for a long time people, at least in England, used to say that words should be looked up “in Murray,” as we now say “in Skeat” or “in Webster.” Not a trace of this usage is left. “Murray” yielded to the anonymous NED [New English Dictionary] and then to OED, with or without the definite article).

Those tireless researchers deserved the recognition they had. But there also were people who formed a circle of correspondents united by their devotion to some journal: Athenaeum, The Academy, and their likes. Most typically, the same subscribers used to send letters to Notes and Queries year in, year out. As a rule, they are only names to me and probably to most of our contemporaries, but the members of that “club” often knew one another or at least knew who the writers were, and being visible in Notes and Queries amounted to a thin slice of international fame. Having run (for the sake of my bibliography of English etymology) through the entire set of that periodical twice, I learned to appreciate the correspondents’ dedication to scholarship and their erudition. I learned a good deal about their way of life, their libraries, and their antiquarian interests, but not enough to write an entertaining essay devoted to any one of them. That is why my series died after the first effort, a post on Dr. Frank Chance (Dr. means “medical doctor” here), and I still hope that one day Oxford University Press will publish a collection of his excellent short articles on English and French subjects.

To be sure, Henry Bradley is not an obscure figure, but even in his lifetime he was never in the limelight. And yet for many years he was second in command at the OED and, when Murray died, replaced him as NO. 1. In principle, the OED, conceived as a historical dictionary, did not have to provide etymologies. But the Philological Society always wanted origins to be part of the entries. Hensleigh Wedgwood was at one time considered as a prospective Etymologist-in-Chief, but it soon became clear that he would not do: his blind commitment to onomatopoeia and indifference to the latest achievements of historical linguistics disqualified him almost by definition despite his diligence and ingenuity. Skeat may not have aspired for that role. In any case, James Murray decided to do the work himself. That he turned out to be such an astute etymologist was a piece of luck.

Beginning with 1884, Bradley became an active participant in the dictionary. According to Bridges, in January 1888 he sent in the first instalment of his independent editing (531 slips). In the same year he was acknowledged as Joint Editor, responsible for his own sections, in 1896 he moved to Oxford, and from 1915, after the death of Murray in July of that year, he served as Senior Editor. In 1928 Clarendon Press published The Collected Papers of Henry Bradley, With a Memoir by Robert Bridges, and it is from this memoir that I have all the dates. About the move to Oxford, Bridges wrote: “He definitely entered into bondage and sold himself to slave henceforth for the Dictionary.” (How many people still remember the poetry of Robert Bridges?)

James Murray was a jealous man. He might have preferred to go on without a senior assistant, but even he was unable to do all the editing alone. It could not be predicted that Bradley would trace the history of words, inherited and borrowed, so extremely well. Once again luck was on the side of the great dictionary. In 1923, when Bradley died, not much was left to do. Even today, despite a mass of new information, the appearance of indispensable dictionaries and databases (to say nothing of the wonders of technology), as well as the publication of countless works on archeology, every branch of Indo-European, and the structure of the protolanguage and proto-society, the original etymologies in the OED more often than not need revision rather than refutation. This fact testifies to Murray’s and Bradley’s talent and to the reliability of the method they used.

Bradley joined the ictionary after Murray read his review of the first installments of the OED (The Academy, February 16, pp. 105-106, and March 1, pp. 141-142; I am grateful to the OED’s Peter Gilliver for checking and correcting the chronology). Bridges wrote about that review: “…its immediate publication revealed to Dr. Murray a critic who could give him points.” But today, 140 years later, one wonders what impressed Murray so much in Bradley’s remarks and what points “the critic” could give him. Bradley did not conceal his admiration for what he had seen, suggested a few corrections, and expressed the hope that “the work [would] be carried to its conclusion in a manner worthy of this brilliant commencement.” It can be doubted that Murray melted at the sight of the compliments: with two exceptions, everybody praised the first fascicles, and those who did not wrote mean-spirited reports. More probably, he sensed in Bradley someone who had a thorough understanding of his ideas and a knowledgeable potential ally (Bradley’s pre-1883 articles were neither numerous nor earth shattering). If such was the case, he guessed well.

Finding word origins was only one small (even if the trickiest) part of the editors’ duties, but my subject is limited to this single aspect of their activities. The title of Bradley’s posthumous volume, The Collected Papers, should not be mistaken for The Complete Works. Nor was such a full collection needed, though some omissions cause regret. Like Murray, Bradley wrote many short notes (especially often to The Academy, of which long before his move to Oxford he was editor for a year). My database contains sixty-five titles under his name. Here are some of them: “Two Mistakes in Littré’s French Dictionary,” “Obscure Words in Middle English,” “The Etymology of the Word god,” “Dialect and Etymology” (the latter in the Transactions of the Yorkshire Dialect Society; Bradley was born in Manchester, so not in Yorkshire), numerous reviews and equally numerous reports, some of whose titles evoke today unexpected associations, as, for example, “F-words in NED” (the secretive year of 1896, when the F-word could not be included!).

Bradley had edited and revised the only full Middle English dictionary then in use. The modest reference to “obscure words” gives no idea of how well he knew that language. And among The Collected Papers the reader will find, among others, his contributions on Beowulf and “slang” to the Encyclopaedia Britannica, ten essays on place names (one of his favorite subjects), and a whole section of literary studies. Those deal with Old and Middle English, and in several cases his opinion became definitive. Bradley’s tone was usually firm (he made no bones about disagreeing with his colleagues) but courteous. Although he sometimes chose to pity an indefensible opinion, the vituperative spirit of nineteenth-century British journalism did not rub off on him. Nor was he loath to admit that his conclusions might be wrong. Temperamentally, he must have been the very opposite of Murray.

One of Bradley’s papers is of special interest to us, and it was perhaps the most influential one he ever wrote. It deals with the chances of reforming English spelling. I will devote a post to it next week.

Anatoly Liberman is the author of Word Origins And How We Know Them as well as An Analytic Dictionary of English Etymology: An Introduction. His column on word origins, The Oxford Etymologist, appears on the OUPblog each Wednesday. Send your etymology question to him care of [email protected]; he’ll do his best to avoid responding with “origin unknown.” Subscribe to Anatoly Liberman’s weekly etymology articles via email or RSS.

Anatoly Liberman is the author of Word Origins And How We Know Them as well as An Analytic Dictionary of English Etymology: An Introduction. His column on word origins, The Oxford Etymologist, appears on the OUPblog each Wednesday. Send your etymology question to him care of [email protected]; he’ll do his best to avoid responding with “origin unknown.” Subscribe to Anatoly Liberman’s weekly etymology articles via email or RSS.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only language articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

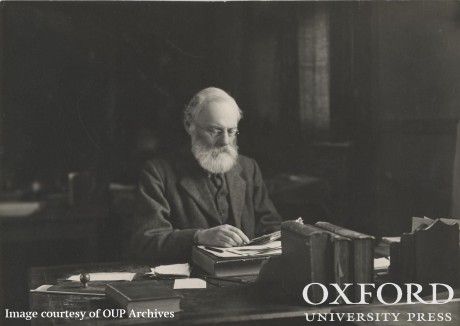

Image credit: Image courtesy of OUP Archives.

The post Unsung heroes of English etymology: Henry Bradley (1845-1923) appeared first on OUPblog.

By: Julia Callaway,

on 4/5/2014

Blog:

OUPblog

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

Language,

oxford english dictionary,

coldplay,

Gwyneth Paltrow,

Canterbury Tales,

Chris Martin,

word histories,

*Featured,

Geoffrey Chaucer,

oxfordwords blog,

Dictionaries & Lexicography,

conscious uncoupling,

Simon Thomas,

uncoupling,

paltrow,

the regiment,

gwyneth,

the oed dates,

site goop,

hoccleve,

the oed defines,

Add a tag

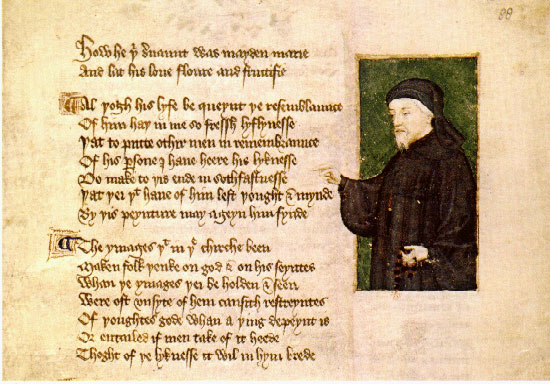

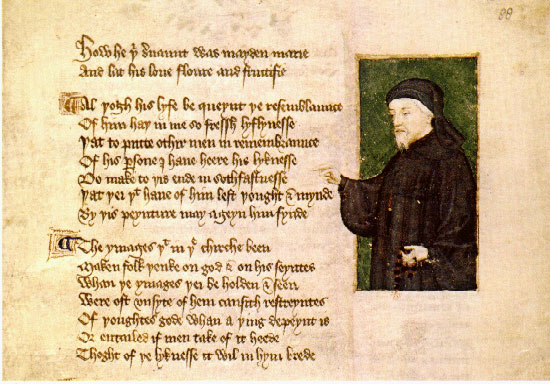

By Simon Thomas

Gwyneth Paltrow and Chris Martin (better known as an Oscar-winning actress and the Grammy-winning lead singer of Coldplay respectively) recently announced that they would be separating. While the news of any separation is sad, we can’t deny that the report also carried some linguistic interest. In the announcement, on Paltrow’s lifestyle site Goop, the pair described the end of their marriage as a “conscious uncoupling.” So … what does that mean?

The phrase was picked up by journalists, commentators, and tweeters around the world. Some called it pretentious, some thought it wise, others simply didn’t know what was going on. Let’s have a look into the Oxford English Dictionary (OED) and see what we can learn about these words.

Conscious is perhaps the less controversial word of the pair. A look through the Oxford Thesaurus of English brings up adjectives like aware, deliberate, intentional, and considered. But did you know that the earliest recorded use of conscious related only to misdeeds? The OED currently dates the word to 1573, with the definition “having awareness of one’s own wrongdoing, affected by a feeling of guilt.” This sense is now confined to literary contexts, but it was only a few decades before the general sense “having knowledge or awareness; able to perceive or experience something” became common. The idea of it being used as an adjective referring to a deliberate action came later, in 1726, according to the OED’s current research.

Portrait of Geoffrey Chaucer by Thomas Hoccleve in the Regiment of Princes

The verb uncouple has an intriguing history. The current earliest evidence in the OED dates to the early fourteenth century, where it means “to release (dogs) from being fastened together in couples; to set free for the chase.” Interestingly, this is found earlier than its opposite (“to tie or fasten (dogs) together in pairs”), currently dated to c.1400 in Sir Gawain and the Green Knight. In c.1386, in the hands of Chaucer and “The Monk’s Tale,” uncouple is given a figurative use:

He maked hym so konnyng and so sowple

That longe tyme it was er tirannye

Or any vice dorste on hym vncowple.

The wider meaning “to unfasten, disconnect, detach” arrives in the early sixteenth century, and that is where things rested for some centuries.

The twentieth century saw another couple of uncouples – one of which is applicable to the Paltrow-Martins, and one of which refers to a very different field. In 1948, a biochemical use is first recorded – which the OED defines “to separate the processes of (phosphorylation) from those of oxidation.” But six years earlier, an American Thesaurus of Slang includes the word as a synonym for “to divorce,” and this forms the earliest example found in the OED sense defined as “to separate at the end of a relationship.” Other instances of uncouple meaning “to split up” can be found in a 1977 Washington Post article and one from the Boston Globe in 1989.

So, despite all the attention given to the term “conscious uncoupling,” people have been uncoupling in exactly the same way as Gwyneth and Chris – and using the same word – since at least 1942. So perhaps not quite as controversial as some commentators suggested.

A version of this article originally appeared on the OxfordWords blog.

Simon Thomas blogs at Stuck-in-a-Book.co.uk.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only language articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Image: Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.

The post Word histories: conscious uncoupling appeared first on OUPblog.

By: Julia Callaway,

on 3/21/2014

Blog:

OUPblog

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

Language,

oxford english dictionary,

French language,

*Featured,

oxfordwords,

Académie Française,

française,

oxfordwords blog,

Dictionaries & Lexicography,

anglicisms,

Dictionnaire de l'Academie Francaise,

Joanna Rubery,

UN French Language Day,

the académiciens,

the académie carry,

the académiciens regularly,

the académie,

and académiciens are,

académie’s,

the dictionnaire,

Add a tag

By Joanna Rubery

It’s official: binge drinking is passé in France. No bad thing, you may think; but while you may now be looking forward to a summer of slow afternoons marinating in traditional Parisian café culture, you won’t be able to sip any fair trade wine, download any emails, or get any cash back – not officially, anyway.

How so? Are the French cheesed off with modern life? Well, not quite: it’s the “Anglo-Saxon” terms themselves that have been given the cold shoulder by certain linguistic authorities in favour of carefully crafted French alternatives. And if you approve of this move, then here’s a toast to a very happy journée internationale de la francophonie on 20 March. But just who are these linguistic authorities, and do French speakers really listen to them?

The Académie française

You may not be aware that 2014 has been dedicated to the “reconquête de la langue française” by the Académie française, that esteemed assembly of academics who can trace their custody of the French language back almost four centuries to pre-revolutionary France. While the recommendations of the académie carry no legal weight, its learned members advise the French government on usage and terminology (advice which is, to their chagrin, not always heeded). The thirty-eight immortels, as they are known (there are currently two vacant fauteuils), maintain that la langue de Molière has been under sustained attack for several generations, from a mixture of poor teaching, poor usage, and – most notoriously – “la montée en puissance de l’anglo-saxon”. Although French can still hold its own as a world language in terms of number of speakers (220 million) and learners (it’s the second most commonly taught language after – well, no prizes for guessing), this frisson of fear is understandable if we cast our eyes back to 1635, when the Académie was formally founded.

At that time, French enjoyed considerable cachet throughout Europe as the medium of communication par excellence for the cultural elite. But in France, where regional languages such as Breton and Picard were widely spoken, the académiciens had the remarkably democratic ambition of pruning and purifying their national tongue in order that it should be clear, elegant, and accessible to all. They nobly undertook to “draw up certain rules for [the] language, and to render it pure, eloquent, and capable of dealing with arts and sciences”. In practical terms, this meant writing a dictionary.

The Académie française, Paris.

Looking up le mot juste

Published nearly 60 years later in 1694, the Dictionnaire de l’Académie française was not the first dictionary of the French language, but it was the first of its kind: a dictionary of “words, rather than things”, which focused on spelling, syntax, register, and above all, “le respect du bon usage”. Intended to advise the honnête homme what (and what not) to say, it has survived three centuries and nine editions to finally appear online as a fascinating record of the evolution of the French language.

You may be tempted to draw parallels between the Dictionnaire de l’Académie française (DAF) and our own Oxford English Dictionary (OED), but in many ways they are fundamentally different. In the English-speaking world, there is no equivalent of the Académie française and its sweeping, egalitarian vision. The OED was conceived (centuries after the DAF) as a practical response to the realization that “existing English language dictionaries were incomplete and deficient” and is generally regarded as a descriptivist dictionary, recording the ways in which words are used, while the DAF is more of a prescriptivist dictionary, recording the ways in which words should be used. While the OED’s entries are liberally sprinkled with literary citations as examples of usage, the DAF has no need for them. And as a historical dictionary, the OED doesn’t ever delete a word from its (digital) pages, whereas the DAF will happily remove words deemed obsolete (and is quite transparent about doing so). Consequently, the OED, with roughly 600,000 headwords, is around ten times bigger than the DAF.

Faux pas in French

However, the digital revolution has allowed both dictionaries to reach out to their readers, albeit in tellingly different ways. While the OED staff appeal to the public for practical help with antedating, the académiciens, faithful to their four-hundred-year-old mission, have pledged to respond to their readers’ questions on usage and grammar in an online forum dedicated to “des esclaircissemens à leurs doutes”.The result, “Dire, Ne Pas Dire”, is a fascinating read, ranging from semantics (can a shaving mirror actually be called a shaving mirror, given that it is not used as a razor?) to politics (a debate over the validity of the trendy English phrase “save the date” on wedding invitations). And it doesn’t take long to see that the Académie’s greatest bête noire by far is the “menace” of the “péril anglais”.

Plus ça change

There may be a sense of déjà-vu here for the académiciens, because grievances over the Anglicization of the French language date back to at least 1788. Some stand firm in their belief that French, with its rich syntax, logical rules, and “impérieuse précision de la pensée”, will eventually triumph again over English, a “divided” language which, in their opinion, risks fragmenting anarchically due its very global nature: “It may well be that, a century from now, English speakers will need translators to be able to understand each other.” Touché.

But many have reached an impasse of despair: the académiciens regularly deplore the “scourges” inflicted on their native tongue by “la langue anglaise qui insidieusement la dévore de l’intérieur” (the English language which is insidiously devouring it from the inside), rendering much French discussion into a kind of “jargon pseudo-anglais” with terms like updater, customiser, and être blacklisté brashly elbowing their way past their French equivalents (mettre à jour, personnaliser, and figurer sur une liste noire respectively). One immortel fears that the increasing use of English is pushing French into a second-class language at home, urging francophones to go on strike.

The Commission générale de terminologie et de néologie

And académiciens are not alone in their attempts to halt the sabotage of the French language: other authorities, with considerably more legal power, are hard at work too. The French government has introduced various pieces of legislation over the past forty years, the most far-reaching being the 1994 Toubon Law which ruled that the French language must be used – although not necessarily exclusively – in a range of everyday contexts. Two years later, the French ministry of culture and communication established the Commission générale de terminologie et de néologie, whose members, supervised by representatives from the Académie, are tasked with creating hundreds of new French words every year to combat the insidious and irresistible onslaught of Anglo-Saxon terminology. French speakers point out that in practice, most of these creations are not well-known and, if they ever leap off the administrative pages of the Journal officiel, rarely survive in the wild. There are, however, a few notable exceptions, such as logiciel and – to an extent – courriel, which have caught on: the English takeover is not quite yet a fait accompli.

It’s worth remembering, too, that language change does not always come from a conservative – or a European – perspective. It was the Québécois who pioneered the feminization of job titles (with “new” versions such as professeure and ingénieure) in the 1970s. Two decades later, the Institut National de la Langue française in France issued a statement giving its citizens carte blanche to choose between this “Canadian” approach and the “double-gender” practice (allowing la professeur for a female teacher, for example). While the Académie française maintain that such “arbitrary feminization” is destroying the internal logic of the language, research among French speakers shows that the “double-gender” approach is gaining in popularity, but also that where there was once clarity, there is now uncertainty over usage.

Perhaps yet more controversially, France has recently outlawed that familiar and – some might argue – quintessentially French title, Mademoiselle, on official documentation: “Madame” should therefore be preferred as the equivalent of “Monsieur” for men, a title which does not make any assumptions about marital status”, states former Prime Minister François Fillon’s ostensibly egalitarian declaration from 2012.

Après moi, le déluge

Meanwhile, the English deluge continues, dragging the French media and universities in its hypnotic wake, both of which are in thrall to a language which – for younger people, at least – just seems infinitely more chic. But the académiciens need not abandon all hope just yet. The immortel Dominique Fernandez has proposed what seems at first like a completely counter-intuitive suggestion: if the French were taught better English to start with, then they could “leave [it] where it ought to be, in the English language, and not in Anglicisms, that hybrid ruse of ignoramuses,” he asserts. Perhaps compulsory English for all will actually bring about an unexpected renaissance of the French language, the language of resistance, in its own home. And if we all end up speaking English instead? Well, c’est la vie.

A version of this article originally appeared on the OxfordWords blog.

Joanna Rubery is an Online Editor at Oxford University Press.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only language articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Image: The Académie française via iStockphoto via OxfordWords blog.

The post Can the Académie française stop the rise of Anglicisms in French? appeared first on OUPblog.

By: Julia Callaway,

on 3/9/2014

Blog:

OUPblog

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

*Featured,

Dictionaries & Lexicography,

History,

Language,

bible,

dictionaries,

America,

British,

oxford english dictionary,

supreme court,

scripture,

oxford dictionaries,

united states constitution,

Oxford Dictionaries Online,

oxfordwords blog,

dictionaries in law,

lynne murphy,

lynneguist,

Add a tag

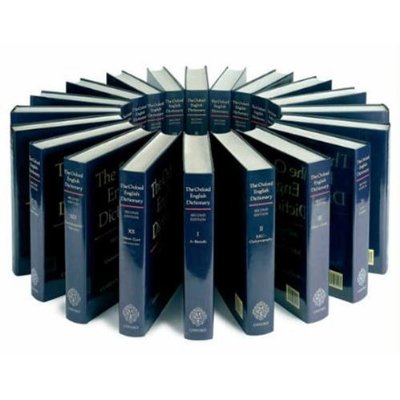

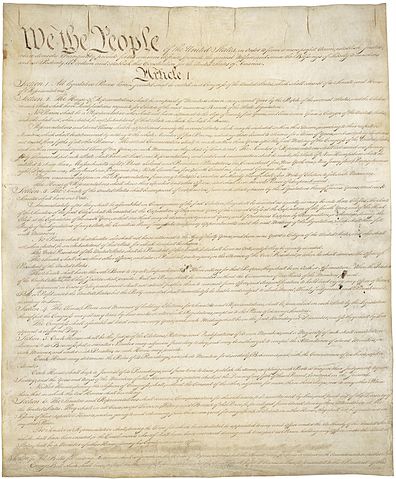

By Lynne Murphy

For 20 years, 14 of those in England, I’ve been giving lectures about the social power afforded to dictionaries, exhorting my students to discard the belief that dictionaries are infallible authorities. The students laugh at my stories about nuns who told me that ain’t couldn’t be a word because it wasn’t in the (school) dictionary and about people who talk about the Dictionary in the same way that they talk about the Bible. But after a while I realized that nearly all the examples in the lecture were, like me, American. At first, I could use the excuse that I’d not been in the UK long enough to encounter good examples of dictionary jingoism. But British examples did not present themselves over the next decade, while American ones kept streaming in. Rather than laughing with recognition, were my students simply laughing with amusement at my ridiculous teachers? Is the notion of dictionary-as-Bible less compelling in a culture where only about 17% of the population consider religion to be important to their lives? (Compare the United States, where 3 in 10 people believe that the Bible provides literal truth.) I’ve started to wonder: how different are British and American attitudes toward dictionaries, and to what extent can those differences be attributed to the two nations’ relationships with the written word?

Our constitutions are a case in point. The United States Constitution is a written document that is extremely difficult to change; the most recent amendment took 202 years to ratify. We didn’t inherit this from the British, whose constitution is uncodified — it’s an aggregation of acts, treaties, and tradition. If you want to freak an American out, tell them that you live in a country where ‘[n]o Act of Parliament can be unconstitutional, for the law of the land knows not the word or the idea’. Americans are generally satisfied that their constitution — which is just about seven times longer than this blog post — is as relevant today as it was when first drafted and last amended. We like it so much that a holiday to celebrate it was instituted in 2004.

Dictionaries and the law

But with such importance placed on the written word of law comes the problem of how to interpret those words. And for a culture where the best word is the written word, a written authority on how to interpret words is sought. Between 2000 and 2010, 295 dictionary definitions were cited in 225 US Supreme Court opinions. In contrast, I could find only four UK Supreme court decisions between 2009 and now that mention dictionaries. American judicial reliance on dictionaries leaves lexicographers and law scholars uneasy; most dictionaries aim to describe common usage, rather than prescribe the best interpretation for a word. Furthermore, dictionaries differ; something as slight as the presence or absence of a the or a usually might have a great impact on a literalist’s interpretation of a law. And yet US Supreme Court dictionary citation has risen by about ten times since the 1960s.

No particular dictionary is America’s Bible—but that doesn’t stop the worship of dictionaries, just as the existence of many Bible translations hasn’t stopped people citing scripture in English. The name Webster is not trademarked, and so several publishers use it on their dictionary titles because of its traditional authority. When asked last summer how a single man, Noah Webster, could have such a profound effect on American English, I missed the chance to say: it wasn’t the man; it was the books — the written word. His “Blue-Backed Speller”, a textbook used in American schools for over 100 years, has been called ‘a secular catechism to the nation-state’. At a time when much was unsure, Webster provided standards (not all of which, it must be said, were accepted) for the new English of a new nation.

American dictionaries, regardless of publisher, have continued in that vein. British lexicography from Johnson’s dictionary to the Oxford English Dictionary (OED) has excelled in recording literary language from a historical viewpoint. In more recent decades British lexicography has taken a more international perspective with serious innovations and industry in dictionaries for learners. American lexicographical innovation, in contrast, has largely been in making dictionaries more user-friendly for the average native speaker.

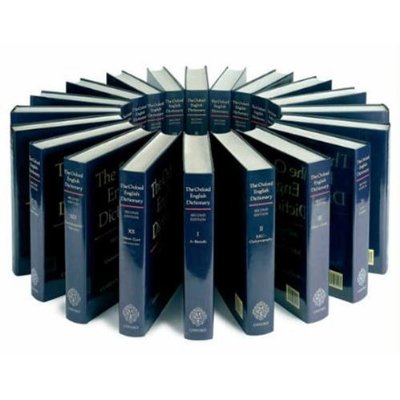

The Oxford English Dictionary, courtesy of Oxford Dictionaries. Do not use without permission.

Local attitudes: marketing dictionaries

By and large, lexicographers on either side of the Atlantic are lovely people who want to describe the language in a way that’s useful to their readers. But a look at the way dictionaries are marketed belies their local histories, the local attitudes toward dictionaries, and assumptions about who is using them. One big general-purpose British dictionary’s cover tells us it is ‘The Language Lover’s Dictionary’. Another is ‘The unrivalled dictionary for word lovers’.

Now compare some hefty American dictionaries, whose covers advertise ‘expert guidance on correct usage’ and ‘The Clearest Advice on Avoiding Offensive Language; The Best Guidance on Grammar and Usage’. One has a badge telling us it is ‘The Official Dictionary of the ASSOCIATED PRESS’. Not one of the British dictionaries comes close to such claims of authority. (The closest is the Oxford tagline ‘The world’s most trusted dictionaries’, which doesn’t make claims about what the dictionary does, but about how it is received.) None of the American dictionary marketers talk about loving words. They think you’re unsure about language and want some help. There may be a story to tell here about social class and dictionaries in the two countries, with the American publishers marketing to the aspirational, and the British ones to the arrived. And maybe it’s aspirationalism and the attendant insecurity that goes with it that makes America the land of the codified rule, the codified meaning. By putting rules and meanings onto paper, we make them available to all. As an American, I kind of like that. As a lexicographer, it worries me that dictionary users don’t always recognize that English is just too big and messy for a dictionary to pin down.

A version of this article originally appeared on the OxfordWords blog.

Lynne Murphy, Reader in Linguistics at the University of Sussex, researches word meaning and use, with special emphasis on antonyms. She blogs at Separated by a Common Language and is on Twitter at @lynneguist.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only language articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

The post How do British and American attitudes to dictionaries differ? appeared first on OUPblog.

By: Alice,

on 2/10/2013

Blog:

OUPblog

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

History,

Biography,

UK,

Dictionaries,

oed,

oxford english dictionary,

lexicographer,

*Featured,

Lexicography & Language,

james murray,

James A. H. Murray,

oxfordwords blog,

Peter Gilliver,

his scriptorium,

scriptorium,

constructed—slips,

Add a tag

Dictionaries never simply spring into being, but represent the work and research of many. Only a select few of the people who have helped create the Oxford English Dictionary, however, can lay claim to the coveted title ‘Editor’. In the first of an occasional series for the OxfordWords blog on the Editors of the OED, Peter Gilliver introduces the most celebrated, Sir James A. H. Murray.

By Peter Gilliver

If ever a lexicographer merited the adjective iconic, it must surely be James Augustus Henry Murray, the first Editor of the Oxford English Dictionary; although what he would have thought about the word being applied to him—in a sense which only came into being long after his death—can only be guessed at, though it seems likely that he would disapprove, given his strongly expressed dislike of the public interest shown in him as a person, rather than in his work. The photograph of him in his Scriptorium in Oxford, wearing his John Knox cap and holding a book and a Dictionary quotation slip, is almost certainly the best-known image of any lexicographer. But there is a lot more to this prodigious man.

If ever a lexicographer merited the adjective iconic, it must surely be James Augustus Henry Murray, the first Editor of the Oxford English Dictionary; although what he would have thought about the word being applied to him—in a sense which only came into being long after his death—can only be guessed at, though it seems likely that he would disapprove, given his strongly expressed dislike of the public interest shown in him as a person, rather than in his work. The photograph of him in his Scriptorium in Oxford, wearing his John Knox cap and holding a book and a Dictionary quotation slip, is almost certainly the best-known image of any lexicographer. But there is a lot more to this prodigious man.

In fact prodigious is another good word for him, for several reasons. He was certainly something of a prodigy as a child, despite his humble background. Born on 7 February 1837 in the Scottish village of Denholm, near Hawick, the son of a tailor, he reputedly knew his alphabet by the time he was eighteen months old, and was soon showing a precocious interest in other languages, including—at the age of 7—Chinese, in the form of a page of the Bible which he laboriously copied out until he could work out the symbols for such words as God and light. Thanks to his voracious appetite for reading, and what he called ‘a sort of mania for learning languages’, he was already a remarkably well-educated boy by the time his formal schooling ended, at the age of 14, with a knowledge of French, German, Italian, Latin, and Greek, and a range of other interests, including botany, geology, and archaeology. After a few years teaching in local schools—he was evidently a born teacher, and was made a headmaster at the age of 21—he moved to London, and took work in a bank. (It was only in 1855, incidentally, that he acquired the full name by which he’s become known: he had been christened plain James Murray, but he adopted two extra initials to stop his correspondence getting mixed up with that of the several other men living in Hawick who shared the name.) He soon began to attend meetings of the London Philological Society, and threw himself into the study of dialect and pronunciation—an interest he had already developed while still in Scotland—and also of the history of English. In 1870 an opening at Mill Hill School, just outside London, enabled him to return to teaching. He began studying for an external London BA degree, which he finished in 1873, the same year as his first big scholarly publication, a study of Scottish dialects which was widely recognized as a pioneering work in its field. Only a year later his linguistic research had earned him his first honorary degree, a doctorate from Edinburgh University: quite an achievement for a self-taught man of 37.

Dr. Murray, Editor

By this time the Philological Society had been trying to collect the materials for a new, and unprecedentedly comprehensive, dictionary of English for over a decade, but the project had gradually lost momentum following the early death of its first Editor, Herbert Coleridge. In 1876 Murray was approached by the London publishers Macmillans about the possibility of editing a dictionary based on the materials collected; the negotiations ultimately came to nothing, but the work which Murray did on this abandoned project was so impressive that when new negotiations were opened with Oxford University Press, and the search for an editor began again, it soon became clear that Murray was the only possible man for the job. After further negotiations, in March 1879 contracts were finally signed, for the compilation of a dictionary that was expected to run to 6,400 pages, in four volumes, and take 10 years to complete—and which Murray planned to edit while continuing to teach at Mill Hill School!

The Dictionary progresses. . .

As we now know, the project would end up taking nearly five times as long as originally planned, and the resulting dictionary ran to over 15,000 pages. Murray soon had to give up his schoolteaching, and moved to Oxford in 1885; even then progress was too slow, and eventually three other Editors were appointed, each with responsibility for different parts of the alphabet. Although for more than three-quarters of the time he worked on the OED there were other Editors working alongside him—he eventually died in 1915—and of course from the beginning he had a staff of assistants helping him, it is without question that he was the Editor of the Dictionary. (He soon had no need of those extra initials: a letter addressed simply to ‘Dr. Murray, Oxford’ would reach him without any difficulty, and he even had notepaper printed giving this as his address.) It was Murray who, in 1879, launched the great ‘Appeal to the English-speaking and English-reading public’ which brought most of the millions of quotation slips from which the Dictionary was mainly constructed—slips sent in from all parts of the English-speaking world, recording English as it was and had been used at all times and in all places. And it was during the early years of the project that all the details of its policy and style had to be settled, and that was Murray’s responsibility; the three later Editors matched their work to his as closely as they could. He was also responsible for more of the 15,000-plus pages of the Dictionary’s first edition than anyone else: the whole of the letters A–D, H–K, O, P, and all but the very end of T, amounting to approximately half of the total.

A dedicated man

What qualities enabled him to achieve this remarkable feat? It hardly needs to be said that he brought an extraordinary combination of linguistic abilities to the task: not just a knowledge of many languages, but the kind of sensitivity to fine nuances in English which all lexicographers need, in an exceptionally highly-developed form. He was also knowledgeable in a wide range of other fields. But one of his most striking qualities was his capacity for hard work, which once again deserves to be called prodigious. Throughout his time working on the Dictionary it was by no means unusual for him to put in 80 or 90 hours a week; he was often working in the Scriptorium by 6 a.m., and often did not leave until 11 p.m. Such a punishing regime would have destroyed the health of a weaker man, but Murray continued to work at this intensity into his seventies.

What qualities enabled him to achieve this remarkable feat? It hardly needs to be said that he brought an extraordinary combination of linguistic abilities to the task: not just a knowledge of many languages, but the kind of sensitivity to fine nuances in English which all lexicographers need, in an exceptionally highly-developed form. He was also knowledgeable in a wide range of other fields. But one of his most striking qualities was his capacity for hard work, which once again deserves to be called prodigious. Throughout his time working on the Dictionary it was by no means unusual for him to put in 80 or 90 hours a week; he was often working in the Scriptorium by 6 a.m., and often did not leave until 11 p.m. Such a punishing regime would have destroyed the health of a weaker man, but Murray continued to work at this intensity into his seventies.

Somehow he managed to combine his work with a vigorous family life; another image of him which deserves to be just as well known as the studious portraits in the Scriptorium is the photograph showing him and his wife surrounded by their eleven children, or the one of him astride a huge ‘sand-monster’ constructed on the beach during one of the family’s holidays in North Wales. He also found time to be an active member of his local community: he was a staunch Congregationalist, regularly preaching at Oxford’s George Street chapel, and an active member of many local societies, and frequently gave lectures about the Dictionary. It is just as well that his conviction of the value of hard work was combined with an iron constitution.

Somehow he managed to combine his work with a vigorous family life; another image of him which deserves to be just as well known as the studious portraits in the Scriptorium is the photograph showing him and his wife surrounded by their eleven children, or the one of him astride a huge ‘sand-monster’ constructed on the beach during one of the family’s holidays in North Wales. He also found time to be an active member of his local community: he was a staunch Congregationalist, regularly preaching at Oxford’s George Street chapel, and an active member of many local societies, and frequently gave lectures about the Dictionary. It is just as well that his conviction of the value of hard work was combined with an iron constitution.

But there is one image which vividly captures another, crucial aspect of this remarkable man, an aspect which arguably underpins his whole approach to life and work. Tellingly, it is not an image of the man himself, but of one of the slips on which the Dictionary was written. The winter of 1896 saw one of Murray’s numerous marathon efforts to complete a section of the Dictionary, in this case the end of the letter D. Very late in the evening of 24 November he was at last able to put the finishing touches to the entry for the word dziggetai (a mule-like mammal found in Mongolia, an animal which Murray would never have seen, and an apt illustration of the Dictionary’s worldwide scope). At 11 o’clock, on the last slip for this word, he wrote: ‘Here endeth Τῷ Θεῷ μόνῳ δόξα.’ The Greek words mean ‘To God alone be the glory’, a phrase which is to be found several times (in various languages) in his writings. For Murray his work on the OED was a God-given vocation. He certainly came to believe that the whole course of his life appeared, in retrospect, to have been designed to prepare him for the work of editing the Dictionary; and perhaps it was only his strong sense of vocation which sustained him through the long years of effort.

A version of this article originally appeared on the OxfordWords blog.

Peter Gilliver is an Associate Editor of the Oxford English Dictionary, and is also writing a history of the OED.

The Oxford English Dictionary (OED) is widely regarded as the accepted authority on the English language. It is an unsurpassed guide to the meaning, history, and pronunciation of 600,000 words — past and present — from across the English-speaking world. Most UK public libraries offer free access to OED Online from your home computer using just your library card number.

Subscribe to the OxfordWords blog via RSS.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only lexicography and language articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

The post ‘Dr. Murray, Oxford’: a remarkable Editor appeared first on OUPblog.

By: Alice,

on 2/9/2013

Blog:

OUPblog

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

Dictionaries,

Multimedia,

oed,

oxford english dictionary,

odnb,

Research Tools,

Oxford Reference,

*Featured,

philip carter,

oxford dictionary of national biography,

oxford dnb,

Oxford Dictionaries Online,

Online Products,

Charlotte Buxton,

National Libraries Day,

Owen Goodyear,

Ruth Langley,

Add a tag