new posts in all blogs

Viewing: Blog Posts Tagged with: Reading The OED, Most Recent at Top [Help]

Results 1 - 5 of 5

How to use this Page

You are viewing the most recent posts tagged with the words: Reading The OED in the JacketFlap blog reader. What is a tag? Think of a tag as a keyword or category label. Tags can both help you find posts on JacketFlap.com as well as provide an easy way for you to "remember" and classify posts for later recall. Try adding a tag yourself by clicking "Add a tag" below a post's header. Scroll down through the list of Recent Posts in the left column and click on a post title that sounds interesting. You can view all posts from a specific blog by clicking the Blog name in the right column, or you can click a 'More Posts from this Blog' link in any individual post.

By: LaurenA,

on 10/29/2009

Blog:

OUPblog

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

Reading,

Reference,

the,

Historical,

Oxford,

A-Featured,

Lexicography,

Dictionaries,

of,

English,

oed,

oxford english dictionary,

Dictionary,

Ammon,

Shea,

Thesaurus,

ammon shea,

Reading The OED,

Historical Thesaurus of the Oxford English Dictionary,

HTOED,

Add a tag

Lauren, Publicity Assistant

Ammon Shea is a vocabularian, lexicographer, and the author of Reading the OED: One Man, One Year, 21,730 Pages. In the videos below, he discusses the evolution of terms like “Love Affair” and names of diseases, as traced in the Historical Thesaurus of the Oxford English Dictionary, demonstrating how language changes and reflects cultural histories. Shea also dives into the HTOED to talk about the longest entry, interesting word connections, and comes up with a few surprises. (Do you know what a “strumpetocracy” is?) Watch both videos after the jump. Be sure to check back all week to learn more about the HTOED.

Love, Pregnancy, and Venereal Disease in the Historical Thesaurus

Click here to view the embedded video.

Inside the Historical Thesaurus

Click here to view the embedded video.

By: Rebecca,

on 11/20/2008

Blog:

OUPblog

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

language,

A-Featured,

Lexicography,

Dictionaries,

oed,

dictionary,

ammon shea,

Reading The OED,

reference books,

Add a tag

Ammon Shea recently spent a year of his life reading the OED from start to finish. Over the next few months he will be posting weekly blogs about the insights, gems, and thoughts on language that came from this experience. His book, Reading the OED, has been published by Perigee, so go check it out in your local bookstore. In the post below Ammon reflects on his visit to talk to 5th and 6th graders.

Are we born with a natural fear of reference books or does it have to be taught to us? This was the question on my mind last week as I was visiting my old grammar school to talk to the 5th and 6th grade classes about dictionaries.

I don’t remember who taught me how to use a dictionary, or when it happened, or at what point I began to  feel apprehensive about this use. But I know that for many of the years between when I first learned to spell and when I realized that I’d been misinterpreting the usage label ‘colloquial’ in the dictionary that I had been plagued by feelings of uncertainty whenever I went to consult a reference work. I’ve been trying to come up with a workshop of sorts that will dispel this uncertainty make the dictionary enjoyable for children, and I hoped that talking with the 11 and 12 year olds would help me in this.

feel apprehensive about this use. But I know that for many of the years between when I first learned to spell and when I realized that I’d been misinterpreting the usage label ‘colloquial’ in the dictionary that I had been plagued by feelings of uncertainty whenever I went to consult a reference work. I’ve been trying to come up with a workshop of sorts that will dispel this uncertainty make the dictionary enjoyable for children, and I hoped that talking with the 11 and 12 year olds would help me in this.

The 5th and 6th graders were considerably more engaged, engaging, and educated that I had thought they would be. I suppose it is common for people who have not done much teaching to make mistakes in gauging the educational level of their subjects, but I still was fairly surprised. Especially when I was talking to the 6th graders about how the meanings of certain words shift over time, and asked if any of them know the word maverick. I knew that some of them would know what it meant, but was not prepared for the 11 year old in the back row who piped up with “Well…I know that today maverick means someone who doesn’t follow convention…but wasn’t it originally an eponymous 19th century word from a cattle rancher in the West who refused to brand his livestock?” Suddenly afraid that I was talking to an entire classroom of etymologists specializing in regionalisms I decided to change the subject and asked what their favorite words were.

It appears that this particular group of sixth graders had been eagerly waiting for someone to come by to ask them about their favorite words, as the next ten minutes were taken up with a cacophony on shouted examples: “Wicked!” “Fer-shizzle!!” “Erudite!!!”

Both classes were highly enthusiastic about discussing language, and needed only the slightest provocation from me (as when I asked ‘what’s a word?’) and they would leap into a classroom-wide shouted argument about meaning and context that resembled a scrum of either befuddled or drunk semanticists:

“A word is a thing.”

“A word is not a thing – a word is the title of a thing.”

“But…what about the word ‘the’…is that the title of a thing?”

“Of course ‘the’ is a title…’the’ title – duh.”

“What about word…is word a word?”

“Oh…my…God…you are such an idiot!”

“Yeah, but what does idiot mean?”

I have no way of knowing whether the children to whom I spoke are representative of their age, but it was certain that they have not yet had their irrepressible enjoyment of language scolded out of them, or a fear of dictionaries bred in. They would make up new words constantly (Socko – a taco made with old socks), ask questions that were unencumbered by embarrassment (‘Doesn’t the word dude also mean butt-hair?’), and had no qualms about being excited about the dictionary (as was evidenced by the 5th grade teacher having to yell at the entire class that they had to put away their dictionaries).

There may indeed be some small grain of truth to the definition of ‘dictionary’ that is provided by Ambrose Bierce in his Devil’s Dictionary (‘A malevolent literary device for cramping the growth of a language and making it hard and inelastic’), but if so, it would appear to not take effect for these students until high school at least.

By: Rebecca,

on 10/30/2008

Blog:

OUPblog

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

Oxford,

jesus,

A-Featured,

Lexicography,

Dictionaries,

oed,

dictionary,

ammon shea,

krebs,

Reading The OED,

know…jesus,

owns,

“hmmm…that’s,

“hmmm…what,

“jesus,

lingerie,

Add a tag

Ammon Shea  recently spent a year of his life reading the OED from start to finish. Over the next few months he will be posting weekly blogs about the insights, gems, and thoughts on language that came from this experience. His book, Reading the OED, has been published by Perigee, so go check it out in your local bookstore. In the post below Ammon reflects on his trip to Oxford.

recently spent a year of his life reading the OED from start to finish. Over the next few months he will be posting weekly blogs about the insights, gems, and thoughts on language that came from this experience. His book, Reading the OED, has been published by Perigee, so go check it out in your local bookstore. In the post below Ammon reflects on his trip to Oxford.

The tired old truism about Americans and the English being two people separated by a common language is something I’ve long been aware of, so when I visited Oxford the other week there were very few difficulties in navigating the differences in speech. What I did find confusing was the way that the Oxfordians talk about their colleges – and one college in particular.

I was having dinner with a group of OUP editors (from the UK) and publicists (from New York), and half-way through the meal the principal of one of the local colleges, one Lord Krebs, stopped by and joined us. He was soon engrossed in conversation with the editors at the other end of the table. I was eavesdropping in an unintentional sort of way, and growing increasingly confused.

I think my confusion began when I overheard the following snippet:

“Hmmm…that’s funny, I didn’t know Jesus was Welsh…”

“You didn’t know Jesus was Welsh?”

As I began listening more intently I suddenly was overcome with the fear that these witty and erudite members of Oxford University Press with whom I was so impressed were actually all adherents of some strange evangelical movement.

“One of my duties for Jesus is to look after the real estate, and do you know…Jesus owns a lot of real estate.”

“Jesus owns real estate?”

“Why yes…tons of it.”

“Well, I’d always known that Jesus was well-off, but not rich.”

“I’d have to say that Jesus is stinking rich.”

“Hmmm…what kind of properties are you talking about?”

“Mostly, Jesus owns a lot of farms in Wales, but all kinds of places really. Did you know that Jesus even owns a lingerie store?”

“Jesus owns a lingerie store!?!?”

At this point the participants in the conversation noticed that all the Americans had stopped talking, and were exhibiting the sort of polite yet strained interest that one reserves for things that are unavoidable and potentially quite discomfiting. It turns out that Lord Krebs is the principal of Jesus College of the University of Oxford (“renowned for being one of the friendliest colleges in Oxford” according to its web site), and the locals unsurprisingly refer to the institution by its first name.

I returned to my meal, secure and comforted by the twin bits of knowledge that Jesus (the historical figure) was not selling naughty underwear and that wherever I visit I will always find the local vernacular something that will delightfully confuse me.

ShareThis

By: Rebecca,

on 8/14/2008

Blog:

OUPblog

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

blog,

Health,

Oxford,

words,

A-Featured,

Lexicography,

Dictionaries,

oed,

dictionary,

ammon shea,

Reading The OED,

gossypiboma,

surgeon,

sponge,

wonderfully,

qualified,

maasai,

helpfully,

mulish,

befell,

Add a tag

Ammon Shea  recently spent a year of his life reading the OED from start to finish. Over the next few months he will be posting weekly blogs about the insights, gems, and thoughts on language that came from this experience. His book, Reading the OED, has been published by Perigee, so go check it out in your local bookstore. In the post below Ammon looks for help finding the etymology of the word “gossypiboma”.

recently spent a year of his life reading the OED from start to finish. Over the next few months he will be posting weekly blogs about the insights, gems, and thoughts on language that came from this experience. His book, Reading the OED, has been published by Perigee, so go check it out in your local bookstore. In the post below Ammon looks for help finding the etymology of the word “gossypiboma”.

On the web site that I recently put up I’ve included my email address, along with the exhortation for anyone who cares to write me with any questions they have about obscure words. I am not any more qualified to answer such questions than most people, and I am certainly less qualified than any lexicographer would be, but that doesn’t stop people from asking questions, or me from attempting to answer them. In some cases it’s seemed that someone will write me with a question because they were too lazy to look it up in the dictionary themselves. I’m always happy to drop whatever I’m supposed to be doing to go look something up in a dictionary, so I do not mind these questions at all, even if they accomplish little, aside of helping me waste some time.

However, this morning I received a question from a surgeon that accomplished two things: it confused me greatly and it reinforced the exceptionally negative view I have of doctors. The letter-writer wanted to know more information about the word gossypiboma (which she then helpfully defined as the word for a retained surgical sponge - “a memento that we surgeons sometimes accidentally leave behind to commemorate our presence in some poor patient’s abdomen.”)

According to the letter writer the word has been in use since the 1970s, and has a wonderfully mulish pedigree (from a mixture of Latin and either Swahili or Maasai).

I have not seen it in any dictionaries, and don’t know when it will work its way in. And so I’ve decided to ask the question myself, through this blog, if anyone has any more information about this wonderfully horrible word.

Has anyone seen it in a dictionary? Or has anyone a certain etymology? Or has anyone had a sponge left inside of them and then had the doctors who left it explain that gossypiboma is the term for what just befell them, followed by a scholarly explanation of how the word came about?

ShareThis

By: Rebecca,

on 7/24/2008

Blog:

OUPblog

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

book,

A-Featured,

Lexicography,

Dictionaries,

dictionary,

ammon shea,

Reading The OED,

keeping notes,

note,

blank,

intentions,

oed,

notes,

Add a tag

Ammon Shea  recently spent a year of his life reading the OED from start to finish. Over the next few months he will be posting weekly blogs about the insights, gems, and thoughts on language that came from this experience. His book, Reading the OED, has been published by Perigee, so go check it out in your local bookstore.In the post below Ammon reflects on note-taking.

recently spent a year of his life reading the OED from start to finish. Over the next few months he will be posting weekly blogs about the insights, gems, and thoughts on language that came from this experience. His book, Reading the OED, has been published by Perigee, so go check it out in your local bookstore.In the post below Ammon reflects on note-taking.

Every so often I find myself engaged in some activity that works out much better than I had expected it to. When this happens I inevitably find myself thinking ‘why don’t I remember to do this all the time?’, as though I could irrevocably change my life for the better, if only I took careful notes of what works and what doesn’t, and then scrupulously followed those notes in all my future endeavors.

But just as inevitably I cast aside these intentions, and far too often find myself engaged in some activity that doesn’t work quite so well as I’d hoped. Of late, I’ve been wondering why I don’t keep notes when I read.

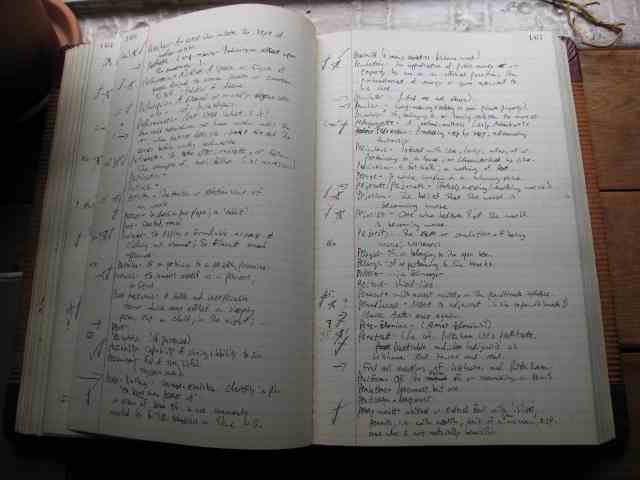

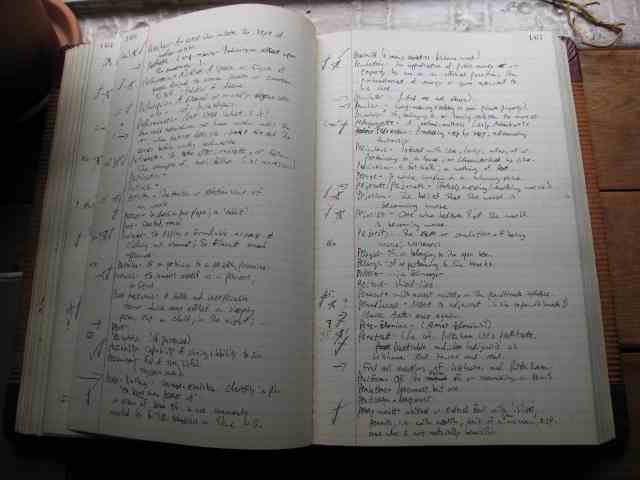

I always keep notes when I read a dictionary; if I don’t I find myself constantly plagued by the feeling that there is a word I can’t remember, somewhere back in the first three letters of the alphabet, and I’ll waste some large portion of a morning going back and fruitlessly searching for it. So when I sat down to read the OED last year I did so with a blank book in which I planned on keeping notes.

Because the OED was a larger dictionary than any other I had read I decided to get a larger book for a  my notes. I found a used book dealer in Massachusetts who had a blank nineteenth century daybook; 500 enormous pages of clean old paper that had been waiting patiently for well over a hundred years for someone to come along and write on them. In it I wrote all the words that I came across that I liked, or the things about which I had questions, or any thoughts that I had about the dictionary as I read it.

my notes. I found a used book dealer in Massachusetts who had a blank nineteenth century daybook; 500 enormous pages of clean old paper that had been waiting patiently for well over a hundred years for someone to come along and write on them. In it I wrote all the words that I came across that I liked, or the things about which I had questions, or any thoughts that I had about the dictionary as I read it.

The book is filled halfway with my scrawls, inkblots, and coffee stains. Sometimes I’ll look through it if I’m looking for some word that slipped out of mind, and sometimes I’ll just pick it up to browse through. It is an extremely condensed and personal version of the OED. While it lacks the majesty and erudition of that work it does do a wonderful job of reminding me why I enjoyed reading it in the first place.

Why don’t I keep notebooks for the other books I read? I’ve tried many different methods of memorializing my books – dog-earing pages that I want to come back to, interleaving sheets of paper with jotted comments, penciling or penning in marginalia. In all cases I have similar results: the beginning of the book is marked with this readerly spoor, but as I progress through the pages the intentions apparently give way to the simple pleasure of reading in the moment, without plans for the future, and the notes and creased pages die off.

Part of me thinks that keeping notes for reading non-reference works is a waste of time. I tell myself that I’ll always remember certain parts of certain books – some writing is so terribly well done that it sears itself into my memory. At least, that’s what I thought, and to prove it to myself this morning I picked up what has long been one of most treasured and well-remembered books, Bohumil Hrabal’s Too Loud a Solitude. It’s a tiny little novel, with an utterly improbable amount of joy and sadness packed into just under a hundred pages. I’ve read it a number of times, and one of the things about it that I remember most clearly is that every single chapter begins with the exact same line: “For thirty-five years now I’ve compacted wastepaper in a hydraulic press…”

Yet when I looked at it this morning I discovered that I was wrong. Many of the chapters begin with some variation of this line, but no two are exactly the same, and some chapters are missing it completely. At first I found this extremely disconcerting - if only I had kept notes when I read this book I never would have spent all these years cherishing a false memory. And then I realized the absurdity of keeping notes for reading a 98 page novella.

My memories of this book are inimitably mine and every bit as real and meaningful as the book itself. The fact that they are graced with the creativity of imprecise recollection gives this book even more of a hold on me. The enjoyment I get from rereading my notes on the OED notwithstanding, I’ll continue to read my books without an eye to the future.

ShareThis

my notes. I found a used book dealer in Massachusetts who had a blank nineteenth century daybook; 500 enormous pages of clean old paper that had been waiting patiently for well over a hundred years for someone to come along and write on them. In it I wrote all the words that I came across that I liked, or the things about which I had questions, or any thoughts that I had about the dictionary as I read it.

my notes. I found a used book dealer in Massachusetts who had a blank nineteenth century daybook; 500 enormous pages of clean old paper that had been waiting patiently for well over a hundred years for someone to come along and write on them. In it I wrote all the words that I came across that I liked, or the things about which I had questions, or any thoughts that I had about the dictionary as I read it.

My daughter graduated this year from St Edmund Hall, Oxford (called Teddy Hall by the Teddies, the students of the college). I couldn’t understand her conversations either: the scout is the cleaner, battels are charges for meals and accommodation, sub fusc is formal dress you have to wear when taking exams, collections are exams.

i still think it odd that the college owns a lingerie store…

what a conversation!

70s comedy moment with Richard O’Sullivan:

-Your tie: is it Christ’s?

-…erm… no, it’s mine.