Welcoming Week is a special time of year. Communities across the country will come together to celebrate and raise awareness of immigrants, refugees and new Americans of all kinds. Whether it’s an event at your local art gallery or showing support on social media, the goal is to let anyone new to America know just how much they are valued and welcomed during what is likely a big transition.

And the biggest transitions are happening for the littlest people.

A new country, a new home, maybe even a new language — that would be enough for any kid — but a new school, too? That subject is exactly what author Anne Sibley O’Brien addresses in her book I’m New Here, new to the First Book Marketplace.

Marissa Wasseluk and Roxana Barillas of the First Book team had the pleasure of speaking with Anne about I’m New Here, the experiences of kids new to America, and what kids can do to help create a welcoming atmosphere.

Marissa: So, and I am sure you get this question all the time, but I’m curious — what inspired or motivated you to create I’m New Here?

It’s funny, it’s such a, “where would you start?” kind of question, but I don’t remember if anyone has ever asked me that point blank because I don’t recall ever putting together this answer before. Over the years of working in schools — especially working with Margy Burns Knight with our nonfiction books: Talking Walls; Who Belongs Here and other multi-racial, multicultural, global nonfiction books — I had a lot of encounters, a lot of discussions, a lot of experiences with immigrant students and I was very aware of the kinds of cross-cultural challenges that children and teachers can experience. For instance, Cambodian children show respect by keeping their eyes down and not looking in the eyes of an adult, especially a teacher. In Cambodian culture adults don’t ever touch children’s heads. So you can immediately imagine how those kinds of things would be quite challenging when a Cambodian child comes into a U.S. classroom and suddenly two of those cultural markers are not only gone, but the opposite is what they need to learn.

Somebody might put their hand on your head — it being out of concern and wanting to make a connection — or they might say “I need you to look at me now” and not recognize that that’s cultural inappropriate for a Cambodian child. So growing that kind of awareness of the challenges that immigrant children face — that was the original impetus for the book. Just collecting some of those stories and raising awareness of how many obstacles immigrant children face. From climate to traditions in speaking and in body language, to food, to learning a new language. Not just learning a new language in terms of how you speak and read and write, but also how you interact with people, how social norms work — they just face such enormous challenges. And there were originally six characters so it was trying to cover everything.

Marissa: The characters that are in the book, they cover a child from Guatemala, a child from Korea, and a child from Somalia — did you work with these specific immigrant communities when you were creating this book?

I spoke to individual experts, such as several Somali interpreters and family liaison experts who work for the multi-lingual, multicultural office of the Portland, ME public schools. So I had that kind of expert advice to respond to what I was writing. But the original ideas mostly came from my observations, my interactions with Somali students in the classrooms that I visited. And then with Korean students I met many, many Korean students here in the US and I had my own background to draw on there.

Marissa: Can you tell me a little bit more about these classrooms that you’ve visited? We talk with a lot of educators who work with Title I schools and they often talk about how reserved the English as a second language students can be. There is a silent phase that a lot of kids go through. Have you observed that and have you shared your book with any of these first generation immigrants?

It’s certainly been shared with many. I actually just shared it with a group of students in a summer school program — about seventy students from third to fifth grade who were from East African countries and some Middle Eastern countries. Most of the group were immigrants and I read the book and then we had a discussion about being new and being welcoming. Of all the student groups that I’ve worked with, they were actually the most effusive and had the most to share in that discussion about what it feels like to be new and what you can do to welcome someone.

Marissa: What were some of the suggestions?

They had all kinds of ideas about what you could say and do to make somebody feel like they were at home. You could take them around, go through a list and say, “this is your classroom, this is your teacher, this is your playground, this is your classmate.”

Roxana: You’re taking me back – a few years back I came to the United States when I was twelve from El Salvador, speaking no English. It hits close to home in terms of the importance of the work you are doing, not just for kids who may not always feel like they belong, but also for the kids who can actually help that process be an easier one.

That is wonderful to hear. I was just struck that they had more suggestions than any group I’d worked with, they could hardly be contained. They had so much they wanted to say and I think it’s very fresh in their minds what welcoming looks like and maybe what did or what didn’t happen for them. So the list that they wrote: welcome to my class, say hi, wave, smile, hello, say this is my classroom, these are my friends, do you want to become friends? these are my parents, this is my family, show them around, this is my chair, this is my house, this is your school, this is my teacher, can you read with me? how’s it going? I live here, where do you live? do you need help? welcome to my school.

That is wonderful to hear. I was just struck that they had more suggestions than any group I’d worked with, they could hardly be contained. They had so much they wanted to say and I think it’s very fresh in their minds what welcoming looks like and maybe what did or what didn’t happen for them. So the list that they wrote: welcome to my class, say hi, wave, smile, hello, say this is my classroom, these are my friends, do you want to become friends? these are my parents, this is my family, show them around, this is my chair, this is my house, this is your school, this is my teacher, can you read with me? how’s it going? I live here, where do you live? do you need help? welcome to my school.

It was the specificity of it that I just loved.

And they said what it felt like to be new. These kids went beyond with the details so they said: scared, nervous, confused, happy, sad, lonely, shy, surprised. Which is what I get with any group that I talk to — but then they wrote: don’t know how to write, don’t know everybody, don’t know what to do, don’t know what they’re saying, don’t know what to say, don’t think you fit in, embarrassed, don’t know how to read books, don’t know what to think, don’t know how to play games, don’t know how to respond, don’t know how to use the computer. So that is a really rich, concrete list.

Marissa: What about educators, how have educators responded to your book?

It’s been pretty phenomenal. The book is in its third printing and it’s just a year old. Actually, it went into its third print run in June. That is by far the fastest that any book of mine has taken off, so there seemed to really be a hunger. There are quite a number of books about an individual immigrant’s story, but I think what people are responding to, what they found useful, is that this book is different because it’s a concept book about the experience of being new and being welcoming, and in that way it works. A particular story can make a deep connection even if your experience is quite different, you recognize things that are similar. But to have one book that outlines what the experience is like, it is very good for discussions. I’ve done more teacher conferences and appearances, especially in the TESOL community, than I did before. Normally I do a lot of schools where I talk to students, but in the past year the majority of my appearances have been for teacher conferences.

Marissa: Have any of them come up to you and told you how it’s resonated with them? Have you met any educators who are immigrants themselves?

Yes, definitely! The TESOL community is full of people who have immigrant backgrounds. I shouldn’t say full, but there is quite a healthy percentage of the TESOL community who come from that background themselves. Partly because schools often recruit someone who’s bilingual, so you tend to get a lot of wonderful richness of people’s life experiences. They might be second generation or they might not have come as a child but they definitely make a strong connection to children who have that experience. I remember, in particular, some very moving statements that people made standing in line waiting to have a book signed. Talking about how it was “their story” or people talking about and being reminded of their own students. When I talked about the book they were in tears thinking about their own students.

Marissa: Ideally, how would you like to see your book being used in a classroom or a child’s home?

I think I see it in two ways. First, for a child who has just arrived and who is in a situation where things are strange; to be able to recognize themselves and see that their experience is reflected in something that makes them feel less lonely and that there is hope. Many, many people have gone through this experience and it can be so difficult but you can get through.

And to the children who are not recent immigrants, who have been part of a community for generations; that it would spark empathy for children, for them to imagine what it would be like if they had that experience. Starting with that universal experience of somehow being new somewhere and to recognize, “oh, I remember what that felt like” and imagine if it was not only a new school, but a new country and a new language and a new culture and new food and new religions and on and on and on. Particularly for them to imagine what they could do, concretely, to examine what the new children are doing and to see how hard they are working, the effort that they are making. And also how their classmates are responding so that the outcome is the whole group building a community together.

To learn more about I’m New Here and Anne’s perspective, watch and listen as she discusses the book and her insights into the experiences of immigrant children.

The post Welcoming Week: Q&A with Author Anne Sibley O’Brien appeared first on First Book Blog.

Earlier this month, just back from a marvelous and productive

MLA Convention in Austin, Texas, I started to write a post in response to an Inside Higher Ed article on

"Selling the English Major", which discusses ways English departments are dealing with the national decline in enrollments in the major. I had ideas about the importance of senior faculty teaching intro courses (including First-Year Composition), the value of getting out of the department now and then, the pragmatic usefulness of making general education courses in the major more topical and appealing, etc.

After writing thousands of words, I realized none of my ideas, many of which are simply derived from things I've observed schools doing, would make much of a difference. There are deeper, systemic problems, problems of culture and history and administration, problems that simply can't be dealt with at the department level. Certainly, at the department level people can be experts at shooting themselves in the foot, but more commonly what I see are pretty good departments having their resources slashed and transferred to science and business departments, and then those pretty good departments are told to do better with less. (And often they do, which only increases the problem, because if they can do so well with half of what they had before, surely they could stand a few more cuts...) I got through thousands of words about all this and then just dissolved into despair.

Then I read a fascinating post from Roger Whitson:

"English as a Division Rather than a Department". It's not really about the idea of increasing enrollment in English programs, though I think some of the suggestions would help with that, but rather with more fundamental questions of what, exactly, this whole discipline even

is. Those are questions I find more exciting than dispiriting, so here are some thoughts on it all, offered with the proviso that these are quick reactions to Whitson's piece and likely have all sorts of holes in them...

The idea of creating a large division and separating it into departments is not one I support, because I think English departments ought to be more, not less, unified, but it nonetheless provides a template for thinking beyond where we are. (I don't think Whitson or Aaron Kashtan, whose proposal on Facebook Whitson built off of, desires a less unified discipline. But without clear mechanisms for encouraging, requiring, and funding interdisciplinarity, the divisions will divide, not multiply.)

The quoted Facebook post in Whitson's piece basically describes the English department at my university, and each of those pieces (literature, composition, linguistics, ESL, English education, creative writing) has some autonomy, more or less. I'm not actually convinced that that autonomy has been entirely healthy, because it's led to resource wars and has discouraged interdisciplinary work (with each little group stuck talking to each other and not talking enough beyond their own area because there's little administrative support for it and, indeed, quite the opposite: the balkanization has, if anything, increased the bureaucracy and given people more busy-work).

English departments need to seek out opportunities for unity and collaboration. I don't see how dividing things even more than they already are would achieve that, unless frequent collaboration were somehow mandated — for instance, one of the best things about

the program I attended for my master's degree at Dartmouth was that it required us to take some team-taught courses, which allowed fascinating interdisciplinary conversations and work. They could do that because they were Dartmouth and had the money to let lots of faculty collaborate. Few schools are willing to budget that way; indeed, at many places the movement is in the other direction: more students taught by fewer faculty.

Nonetheless, though I am skeptical of separating English departments more than they already are, I like some of Whitson's proposals for ways to reconfigure the idea of what we do and who we are and could be. Even the simple act of using these ideas as jumping-off points for (utopian) conversation is useful.

PlanetarityHere's a key point from Whitson: "I propose asking for more diverse hires by illustrating how important marginalized discourses are to the fields we study, while also investing heavily in opportunities for new interdisciplinary collectives and collaborations." (Utopian, but we're here for utopian discussion, not the practicalities of convincing the Powers That Be of the value of such an iconoclastic, and likely expensive, approach...)

This connects to a lot of conversations I observed or was part of at MLA, particularly among people in the Global Anglophone

Forum (where nobody seems to like the term "global anglophone"). Discussions of the

difficulties for scholars of work outside the US/Britosphere were common. At least on the evidence of job ads, it seems departments are, overall, consolidating away from such areas as postcolonial studies and toward broader, more general, and often more US/UK-centric curriculums. The center is reasserting itself curricularly, defining margins as extensions, roping them into its self-conception and nationalistic self-justification. The effect of austerity on humanities departments has been devasting for diversity of any sort.

I like the idea of "Reading and Writing Planetary Englishes" as a replacement for English Lit, ESL, and parts of Rhet/Comp. Heck, I like it as a replacement for English departments generally. It's not perfect, but nothing is, and "English" is such a boring, imposing term for our discipline...

(Where Comparative Literature — "Reading and Writing Planetary Not-Englishes" — fits within that, I don't know, and it's a question mostly unaddressed in Whitson's post and will remain unaddressed here because questions of literature in translation and literature in languages other than English are too big for what I'm up to at the moment. They are necessary questions, however.)

Spivak's idea of "planetarity" ("rather," as she says, "than continental, global, or worldly" [

Death of a Discipline 72]) is well worth debating, and may be especially appealing in these days of seemingly endless discussion of "the anthropocene" — but what exactly "planetarity" means to Spivak is not easy to pin down. (She can be an infuriatingly vague writer.) Here's one of the most concrete statements on it from

Death of a Discipline:

If we imagine ourselves as planetary subjects rather than global agents, planetary creatures rather than global entities, alterity remains underived from us; it is not our dialectical negation, it contains us as much as it flings us away. And thus to think of it is already to transgress, for, in spite of our forays into what we metaphorize, differently, as outer and inner space, what is above and beyond our own reach is not continuous with us as it is not, indeed, specifically discontinuous. We must persistently educate ourselves into this peculiar mindset. (73)

A more comprehensible statement on planetarity appears in Chapter 21 of

An Aesthetic Education in the Era of Globalization, "World Systems and the Creole":

The experimental musician Laurie Anderson, when asked why she chose to be artist-in-residence at the National Aeronautic and Space Administration, put it this way: "I like the scale of space. I like thinkng about human beings and what worms are. We are really worms and specks. I find a certain comfort in that."

She has put it rather aggressively. That is not my intellectual style, but my point is close to hers. You see how very different it is from a sense of being the custodians of our very own planet, for god or for nature, although I have no objection to such a sense of accountability, where our own home is our other, as in self and world. But that is not the planetarity I was talking about. (451)

On the next page, she makes a useful statement: "We cannot read if we do not make a serious linguistic effort to enter the epistemic structures presupposed by a text." (Technically, yes, we

can read [decode dictionary meanings of words] without such effort, but whatever understanding we come to will be narcissistic, solipsistic.)

And then on p.453: "...I have learned the hard way how dangerous it is to confuse the limits of one's knowledge with the limits of what can be known, a common problem in the academy."

Spivak (here and elsewhere) exhorts us to give up on totalizing ideas. She quotes Édouard Glissant on the infinite knowledge necessary to understand cultural histories and interactions: "No matter," Glissant says, "how many studies and references we accumulate (though it is our profession to carry out such things properly), we will never reach the end of such a volume; knowing this in advance makes it possible for us to dwell there. Not knowing the totality does not constitute a weakness."

That could be another motto for our new approach: "Not knowing the totality does not constitute a weakness."

What can be known, then, if not a totality, a thing to be mastered? Our limitations.

What I personally like about transnational, global, planetary, etc. approaches is that their impossibility is obvious and any pretense toward totalized knowledge is going to be laughed at, as it should be.

One point Whitson makes that I disagree with, or at least disagree with the phrasing of, is: "Most undergraduate students in English do not have a good grasp of rhetorical devices (

kairos, chaismus, prosopopoeia) and these would replace 'close reading' (a term that lacks the specificity of the more developed rhetorical tradition) in student learning outcomes and primary classes."

Reading is more than rhetorical analysis. "Close reading" may have a bad reputation, and in some of the ways it's used it deserves that bad reputation, but it remains a useful term for a necessary skill. Especially as we think about ways of communicating what we do to audiences skeptical of the humanities generally, a term like "close reading", which can be understood by people who aren't specialists, seems to me less alienating, and less likely to produce misunderstandings, than "rhetoric". But that may just be my own dislike of the word "rhetoric" and my general feeling that rhetorical analysis is, frankly, dull. (There's a reason I'm not a rhet/comp PhD, despite being at a great school for it.) I wouldn't pull a Whitson and say "We must have no rhetorical analysis and only close reading!" That's silly. There are plenty of reasons to teach rhetorical analysis in introductory and advanced forms. There are also many good reasons to teach and encourage close reading. Making it into an opposition and a zero sum game is counterproductive. After all, rhetorical analysis requires close reading and some close reading requires rhetorical analysis.

In any case, instead of debating rhetorical analysis vs. close reading vs. whatever, what I think we ought to be looking at first is the seemingly simple activity of making meaning from what we read. That unites a lot of approaches with productive questions. (John Ciardi's title

How Does a Poem Mean? has been a guiding, and fruitful, principle of my own reading for a long time.) From there, we can then begin to talk about

interpretive communities, systems of textual analysis, etc: ways of reading, and ways of making sense of texts. Certainly, that includes methods of argument and persuasion. But also much more.

There's much to learn from the field of rhetoric and composition on all that. (In fact, a term from rhet/comp,

discourse communities, can be quite useful here if applied both to the act of reading and the act of writing.) Reading should not — cannot — be the province only of literary scholars. A

recent issue of Pedagogy offers some fascinating articles on teaching reading from a comp/rhet point of view. Further, coming back to Spivak, it seems to me that her work, for all its interdisciplinarity, frequently demonstrates ways that readers have been led astray by not reading closely enough, and her own best work is often in her close readings of texts.

Whitson proceeds to a utopian idea of planetarity (one inherent in Spivak) as a way of broadening ideas of literature beyond the human. This would certainly make room for eco-critics, anthropocene-ists, animal studies folks, etc. This isn't my own interest, and I will admit to quite a lot of skepticism about broadening the idea of "literature" so much that it becomes meaningless, but it's clear that we need such a space within English departments, even for people who think plants write lit. Our departments ought to contain multitudes.

MediaI've taught media courses, and obviously have an interest in, particularly,

cinema. I don't think most such studies belong in English departments, so I am inclined to like the idea of it as a separate department within a general division. While there are plenty of English teachers who teach film and media well, and as an academic field it has some of its origins there, cinema especially seems to me to need people who have significant understanding of visual and dramatic arts. (Just as "new media" [now getting old] folks probably need some understanding of basic computer science.)

Media studies is inherently a site of interdisciplinary work, and that's a good thing. Working side-by-side, people who are trained in visual arts, theatre arts, technologies, etc. can produce new ways of knowing the world.

Something that media studies can do especially well is mix practitioners and analysts. Academia really likes to separate the "practical" people from the "theory" people. This is an unfortunate separation, one that has been detrimental to English departments especially, as literary scholars and writers are too often suspicious of each other. (I'll spare you my rant about how being both a literary scholar and a creative writer is unthinkable in conventional academic English department discourse. Another time.) You'll learn a lot about understanding cinema by taking a film editing class, just as you'll learn a lot about understanding literature by taking a creative writing class. Indeed, I often think the benefit of writing workshops (and their ilk) is not in how they produce better writers, but in how they may enable better readers.

On the other hand, and to argue in some ways against myself, writing and reading teachers ought to be well versed in media, because media mediates our lives and thoughts and reading and writing. To what extent should a department of reading and writing be focused on media, I don't know. Media tends to take over. It's flashy and attracts students. But one thing I fear losing is the

refuge of the English department — the one place where we can escape the flash and fizz of techno-everything, where we can sit and think about a sentence written on an old piece of paper for a while.

EducationI'm less convinced by Whitson's arguments about a division of "Composition Pedagogy and English Education". Why put Composition with English Education and not put some literary study there? Is literary study inherent in "English Education"? Why separate Composition, though? Why not call it "Teaching Reading and Writing"? Perhaps I just misunderstand the goals with this one.

It seems to me that English Education should be some sort of meta-discipline. It doesn't make much sense as a department unto itself in the scheme Whitson sets up, or most schemes, for that matter. Any sort of educational field is very difficult to set up well because it requires students not only to learn the material of their area, but to learn then how to teach that material effectively.

To me, it makes more sense to spread discussion of pedagogy throughout all departments, because one way to learn things is to try to teach them. Ideas about education, and practice at teaching, shouldn't be limited only to people who plan to become teachers, though they may need more intensive training in it.

If we want to be radical about how we restructure the discipline, integrating English Education more fully into the discipline as a whole, rather than separating it out, would be the way to go.

WritingWhitson proposes merging creative and professional writing as one department in the division. This is an interesting idea, but I'm not convinced. Again, my own prejudices are at play: in my heart of hearts, I don't think undergraduates should major in writing. I think there should be writing courses, and there should be lots of writers employed by English departments, but the separation of writing and reading is disastrous at the undergraduate level, leading to too many writers who haven't read nearly enough and don't know how to read anything outside of their narrow, personal comfort zone.

In the late '90s, Tony Kushner scandalized the Association of Theatre in Higher Education's annual conference with

a keynote speech in which he (modestly) proposed that all undergraduate arts majors be abolished. (It was published in the January 1998 issue of

American Theatre magazine.) It's one of my favorite things Kushner has ever written. The whole thing is worth reading, but here's a taste:

And even if your students can tell you what iambic pentameter is and can tell you why anyone who ever sets foot on any stage in the known universe should know the answer to that and should be able to scan a line of pentameter in their sleep, how many think that "materialism" means that you own too many clothes, and "idealism" means that you volunteer to work in a soup kitchen? And why should we care? When I first started teaching at NYU, I also did a class at Columbia College, and none of my students, graduate or undergraduate (and almost all the graduate students were undergraduate arts majors--and for the past 10 years Columbia has had undergraduate arts majors), none of them, at NYU or Columbia, knew what I might mean by the idealism/materialism split in Western thought. I was so alarmed that I called a philosophy teacher friend of mine to ask her if something had happened while I was off in rehearsal, if the idealism/materialism split had become passe. She responded that it had been deconstructed, of course, but it's still useful, especially for any sort of political philosophy. By not having even a nodding acquaintance with the tradition I refer to, I submit that my students are incapable of really understanding anything written for the stage in the West, and for that matter in much of the rest of the world, just as they are incapable of reading Plato, Aristotle, Hegel, Marx, Kristeva, Judith Butler, and a huge amount of literature and poetry. They have, in essence, been excluded from some of the best their civilization has produced, and are terribly susceptible, I would submit, to the worst it has to offer.

What I would hope you might consider doing is tricking your undergraduate arts major students. Let them think they've arrived for vocational training and then pull a switcheroo. Instead of doing improv rehearsals, make them read The Death of Ivan Illych and find some reason why this was necessary in learning improv. They're gullible and adoring; they'll believe you. And then at least you'll know that when you die and go to the judgment seat you can say "But I made 20 kids read Tolstoy!" and this, I believe, will count much to your credit. And if you are anything like me, you'll need all the credits you can cadge together.

Call it the pedagogy of pulling a switcheroo. A good pedagogy, at least sometimes. It doesn't have to be, indeed should not be, limited to Western classics, as Kushner (inadvertently?) implies, and the program he calls for would not be so limited, because the kinds of conversations that he wants students to be able to recognize and join are ones that inevitably became (if they weren't already) transnational, global, even maybe a bit planetary.

So yes, if

I were emperor of universities, I'd abolish undergraduate arts majors, but keep lots of artists as undergraduate teachers. I'd also let the artists teach whatever the heck they wanted. Plenty of writers would be better off teaching innovative classes that aren't the gazillionth writing workshop of their career. Boxing writers into teaching only writing classes is a pernicious practice, one that perpetuates the idea that the creation of literature and the study of literature are separate activities.

But let's come back to Whitson's first proposal: planetarity and the making of textual meaning.

My own inclination is not to separate so much, but to seek out more unities. What unites us? That we study and practice ways of reading and ways of writing. We should encourage more reading in writing classes and more varied types of writing in reading classes. We should toss out our inherited, traditional nationalisms and look at other ways that texts flow around us and around not-us. (Writers do. What good writer was only influenced by texts from one nation?) We should seek out the limits of our knowledge, admit them, challenge them, celebrate them.

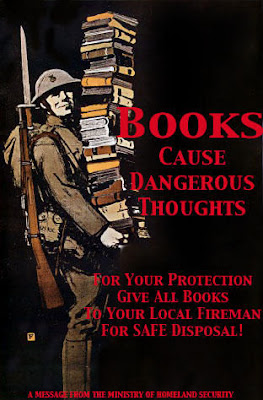

Imagination Perhaps what we should think about is imagination. We need more imagination, and we need to educate and promote imagination. So many of the problems of our world stem from failures of imagination — from the

fear of imagination. If you want to be a radical educator, be an educator who inspires students to imagine in better, fuller, deeper ways. The conservative forces of culture and society promote exactly the opposite, because the desire of the status quo is to produce unimaginative (unquestioning, obedient) subjects.

English departments, like arts departments and philosophy departments, are marvelously positioned to encourage imagination. Any student who enters an English class should leave with an expanded imagination. Any student who studies to become an English teacher should be trained in the training of imaginations. We should all be advocates for imagination, activists for its value, its necessity.

One of the best classes I've ever taught was called Writing and the Creative Process. (You can find links to a couple of the syllabi on my

teaching page, though they can't really give a sense of what made the courses work well.) It was a continuously successful course in spite of me. The stakes were low, because it was an introductory course, and yet the learning we all did was sometimes life-changing. This was not my fault, but the fault of having stumbled into a pedagogy that gave itself over entirely to the practice of creativity, which is to say the practice of imagination. Because it was a pre-Creative Writing class, the focus wasn't even on

becoming better writers but rather on

becoming more creative (imaginative) people. That was the key to the success. Becoming a better writer is a nice goal, but becoming a more creative/imaginative person is a vital goal. Were I titling it, I'd have called that course Writing and Creative Process

es, because one of the things I seek to help the students understand is that there is no one process for either writing or for thinking creatively. But no matter. Just by having to think about, talk about, and practice creativity a couple times a week, we made our lives better. I say

we, because I learned as much by teaching that class as the students did; maybe more.

English departments should become departments of writing, reading, and thinking with creative processes.

I began with Spivak, so I'll come back to her, this time from her recent book

Readings:

And today I am insisting that all teachers, including literary criticism teachers, are activists of the imagination. It is not a question of just producing correct descriptions, which should of course be produced, but which can always be disproved; otherwise nobody can write dissertations. There must be, at the same time, the sense of how to train the imagination, so that it can become something other than Narcissus waiting to see his own powerful image in the eyes of the other. (54)

Training — encouraging, energizing — the imagination means a training in aesthetics, in techniques of structure, in ways of valuing form, in how we find and recognize and respond to the beautiful and sublime.

I'm persuaded by Steve Shaviro's arguments in

No Speed Limit about aesthetics as something at least unassimilable by neoliberalism (if not in direct resistance to it): "When I find something to be beautiful, I am 'indifferent' to any uses that thing might have; I am even indifferent to whether the thing in question actually exists or not. This is why aesthetic sensation is the one realm of existence that is not reducible to political economy." (That's just a little sample. See

"Accelerationist Aesthetics" for more elaboration, and the book for the full argument.)

Because the realm of the aesthetic has some ability to sit outside neoliberalism, it is in many ways the most radical realm we can submit ourselves to in the contemporary world, where neoliberalism assimilates so much else.

But training the imagination is not only an aesthetic education, it's also epistemological. Spivak again:

An epistemological performance is how you construct yourself, or anything, as an object of knowledge. I have been consistently asking you to rethink literature as an object of knowledge, as an instrument of imaginative activism. In Capital, Volume 1 (1867), for example, Marx was asking the worker to rethink him/herself, not as a victim of capitalism but as an "agent of production". That is training the imagination in epistemological performance. This is why Gramsci calls Marx's project "epistemological". It is not only epistemological, of course. Epistemological performance is something without which nothing will happen. That does not mean you stop there. Yet, without a training for this kind of shift, nothing survives. (Readings 79-80)

If we're seeking, as Whitson calls us to, to create more diverse (and imaginative) departments of English, then perhaps we can do so by thinking about ways of approaching aesthetics and epistemology. We can be agents of imagination. We don't need nationalisms for that, and we don't need to strengthen divisive organizational structures that have riven many an English department.

We can — we must — imagine better.

It’s fairly common knowledge that languages, like people, have families. English, for instance, is a member of the Germanic family, with sister languages including Dutch, German, and the Scandinavian languages. Germanic, in turn, is a branch of a larger family, Indo-European, whose other members include the Romance languages (French, Italian, Spanish, and more), Russian, Greek, and Persian.

Being part of a family of course means that you share a common ancestor. For the Romance languages, that mother language is Latin; with the spread and then fall of the Roman empire, Latin split into a number of distinct daughter languages. But what did the Germanic mother language look like? Here there’s a problem, because, although we know that language must have existed, we don’t have any direct record of it.

The earliest Old English written texts date from the 7th century AD, and the earliest Germanic text of any length is a 4th-century translation of the Bible into Gothic, a now-extinct Germanic language. Though impressively old, this text still dates from long after the breakup of the Germanic mother language into its daughters.

How does one go about recovering the features of a language that is dead and gone, and which has left no records of itself in spoken or written form? This is the subject matter of linguistic necromancy – or linguistic reconstruction, as it is more conventionally known.

The enterprise, dubbed “darkest of the dark arts” and “the only means to conjure up the ghosts of vanished centuries” in the epigraph to a chapter of Campbell’s historical linguistics textbook, really got off the ground in the 1900s due to a development of a toolkit of techniques known as the comparative method.

Crucial to the comparative method was a revolutionary empirical finding: the regularity of sound change. Though it has wide-reaching implications, the basic finding is simple to grasp. In a nutshell: it’s sounds that change, not words, and when they change, all words which include those sounds are affected.

Let’s take an example. Lots of English words beginning with a p sound have a German counterpart that begins with pf. Here are some of them:

- English path: German Pfad

- English pepper: German Pfeffer

- English pipe: German Pfeife

- English pan: German Pfanne

- English post: German Pfoste

If the forms of words simply changed at random, these systematic correspondences would be a miraculous coincidence. However, in the light of the regularity of sound change they make perfect sense. Specifically, at some point in the early history of German, the language sounded a lot more like (Old) English. But then the sound p underwent a change to pf at the beginning of words, and all words starting with p were affected.

There’s much more to be said about the regularity of sound change, since it underlies pretty much everything we know about language family groupings. (If you’re interested in finding out more, Guy Deutscher’s book The Unfolding of Language provides an accessible summary.) But for now let’s concentrate on its implications for necromantic purposes, which are immense.

If we want to invoke the words and sounds of a long-dead language like the mother language Proto-Germanic (the ‘proto-’ indicates that the language is reconstructed, rather than directly evidenced in texts), we just need to figure out what changes have happened to the sounds of the daughter languages, and to peel them back one by one like the layers of an onion. Eventually we’ll reach a point where all the daughter languages sound the same; and voilà, we’ve conjured up a proto-language.

There’s more to living languages than just sounds and words though. Living languages have syntax: a structure, a skeleton. By contrast, reconstructed protolanguages tend to look more like ghosts: hauntingly amorphous clouds of words and sounds. There are practical reasons why the reconstruction of proto-syntax has lagged behind. One is simply that our understanding of syntax, in general, has come a long way since the work of the reconstruction pioneers in the 19th century.

Another is that there is nothing quite like the regularity of syntactic change in syntax: how can we tell which syntactic structures correspond to each other across languages? These problems have led some to be sceptical about the possibility of syntactic reconstruction, or at any rate about its fruitfulness. Nevertheless, progress is being made. To take one example, English is a language that doesn’t like to leave out the subject of a sentence. We say “He speaks Swahili” or “It is raining”, not “Speaks Swahili” or “Is raining”. Though most of the modern Germanic languages behave the same, many other languages, like Italian and Japanese, have no such requirement; speakers can include or omit the subject of the sentence as the fancy takes them. Was Proto-Germanic like English, or like Italian or Japanese, in this respect? Doing a bit of necromancy based on the earliest Germanic written records suggests that Proto-Germanic was, like the latter, quite happy to omit the subject, at least under certain circumstances.Of course the issue is more complex than that – Italian and Japanese themselves differ with regard to the circumstances under which subjects can be omitted.

Slowly but surely, though, historical linguists are starting to add skeletons to the reanimated spectres of proto-languages.

The post Linguistic necromancy: a guide for the uninitiated appeared first on OUPblog.

That is wonderful to hear. I was just struck that they had more suggestions than any group I’d worked with, they could hardly be contained. They had so much they wanted to say and I think it’s very fresh in their minds what welcoming looks like and maybe what did or what didn’t happen for them. So the list that they wrote: welcome to my class, say hi, wave, smile, hello, say this is my classroom, these are my friends, do you want to become friends? these are my parents, this is my family, show them around, this is my chair, this is my house, this is your school, this is my teacher, can you read with me? how’s it going? I live here, where do you live? do you need help? welcome to my school.

That is wonderful to hear. I was just struck that they had more suggestions than any group I’d worked with, they could hardly be contained. They had so much they wanted to say and I think it’s very fresh in their minds what welcoming looks like and maybe what did or what didn’t happen for them. So the list that they wrote: welcome to my class, say hi, wave, smile, hello, say this is my classroom, these are my friends, do you want to become friends? these are my parents, this is my family, show them around, this is my chair, this is my house, this is your school, this is my teacher, can you read with me? how’s it going? I live here, where do you live? do you need help? welcome to my school.

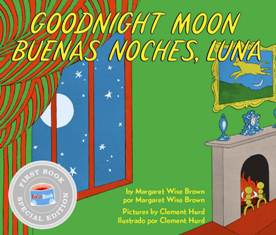

For generations, American families have gathered together to read the cherished children’s book, Goodnight Moon, as part of their bedtime routine. Today, with Harper Collins Children’s Books, we are making the iconic title accessible to millions more families in a bilingual edition for the very first time.

For generations, American families have gathered together to read the cherished children’s book, Goodnight Moon, as part of their bedtime routine. Today, with Harper Collins Children’s Books, we are making the iconic title accessible to millions more families in a bilingual edition for the very first time.

(snaps)