new posts in all blogs

Viewing: Blog Posts Tagged with: pedagogy, Most Recent at Top [Help]

Results 1 - 11 of 11

How to use this Page

You are viewing the most recent posts tagged with the words: pedagogy in the JacketFlap blog reader. What is a tag? Think of a tag as a keyword or category label. Tags can both help you find posts on JacketFlap.com as well as provide an easy way for you to "remember" and classify posts for later recall. Try adding a tag yourself by clicking "Add a tag" below a post's header. Scroll down through the list of Recent Posts in the left column and click on a post title that sounds interesting. You can view all posts from a specific blog by clicking the Blog name in the right column, or you can click a 'More Posts from this Blog' link in any individual post.

I demonstrate hope.

Or the hope for hope. Or just more unanswerable holes.

—Mary Biddinger, "Beatitudes"

(I keep writing and rewriting this post.)

I thought I knew what I felt about the academic controversy du jour (a letter sent by a University of Chicago dean to incoming students, telling them not to expect trigger warnings, that academia is not a safe space, that open discussion requires them to listen to speakers they disagree with, etc.) — but I kept writing and rewriting, conversing and re-conversing with friends, and every time I didn't know more than I knew before.

Overall, I don't think this controversy is about trigger warnings, safe spaces, etc. Overall, I think it is about power and access to power. But then, overall I think most controversies are about power and access to power.

Overall—

The questions around trigger warnings, safe spaces, and campus speakers are complicated, and specific situations must be paid attention to, because universal, general statements are too distorting to be useful.

(I keep writing and rewriting this post.)

Perhaps headings will help:

Academic Freedom

I want academic freedom for everyone at educational institutions: faculty, students, staff. That said, as philosophers have shown for ages, defining what constitutes freedom requires argument, negotiation, even compromise, because one person's freedom may be another person's restriction.

Power

The University of Chicago dean's letter is primarily an expression of power and only secondarily about trigger warnings, safe spaces, and campus speakers. Though vastly more minor, it rhymes with the actions of the Long Island University Brooklyn administration, who locked out all members of the faculty union. Both are signs of things to come. The LIU action was union busting to consolidate administrative power; the UC dean's letter was the deployment of moral panic to consolidate administrative power.

Moral Panic

For the most part, the controversy over trigger warnings, safe spaces, etc. seems to me right now to be a moral panic, and much of the discourse around these things is highly charged not because of the specific policies and actual events — or not only because of the specific policies and actual events — but because of what they stand for in our minds.

Culture War

This moral panic plays into a larger culture war, one not limited to university campuses (indeed, the rise of Donald Trump as a political candidate also seems to me part of that larger war — and "war" is not too strong a word for it).

Tough Love and Hard Reality

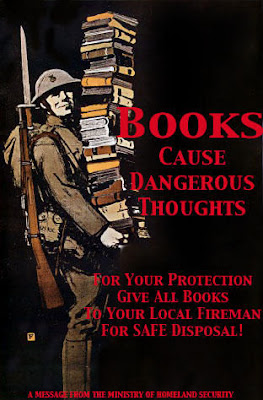

Ever since I was in high school (at the latest) I have vehemently disliked the rhetoric of "tough love pedagogy" and "hard reality" that infuses current discussions of "coddled" students. I said on Twitter that such rhetoric seems to me arrogant, aggressive, and noxiously macho. I have not yet seen someone who advocates such policies and pedagogies do anything to get out of their own comfort zones, for instance by giving away their power and wealth and actively undermining whatever privilege they hold. I would take their position more seriously if they did so.

Comfort/Discomfort

That said, I think it's important to recognize that "comfort" and "discomfort" are broad terms with many meanings, and that students will, indeed, feel a kind of discomfort when encountering material that is new to them, that presents a worldview different from their own, etc. That seems healthy to me and entirely to be desired. (Perhaps we are trying to fit too much into the comfort/discomfort dichotomy. Or perhaps I am trying to restrict it too much.) There must be a way to value the challenging, critical pedagogy of, for instance, Women's Studies courses and Critical Race Theory courses without valorizing the sadism of the arrogant, aggressive, noxiously macho teacher whose primary desire from students is that they worship him as a guru, and whose primary pedagogy is to beat the wrongness out of everyone who steps foot in his classroom.

Perhaps other people's words will help. Here are some readings for homework:

The Ahmed and Nyong'o pieces are foundational; even if we end up disagreeing with them (do we? who "we"?), they help us focus on things that matter. The piece by Kevin Gannon is good at seeing how the "surface veneer of reasonableness" works in the dean's letter, and Gannon is also good at suggesting some of what this moral panic achieves — who benefits and why. Angus Johnston's post is useful for showing some of the complexities of the issues once we start talking about specific instances and policies. Henry Farrell highlights how this controversy is part of the institution of the university. Henry Giroux and the

undercommoners offer radical explosions.

(I keep writing and rewriting this post.

It is full of unanswerable holes.)

My sense of the concept of "moral panic" comes from

Policing the Crisis by Stuart Hall, et al.:

To put it crudely, the "moral panic" appears to us to be one of the principal forms of ideological consciousness by means of which a "silent majority" is won over to the support of increasingly coercive measures on the part of the state, and lends its legitimacy to a "more than usual" exercise of control. ... Their typical [early] form is that of a dramatic event which focuses and triggers a local response and public disquiet. Often as a result of local organising and moral entrepreneurship, the wider powers of the control culture are both alerted (the media play a crucial role here) and mobilised (the police, the courts). The issue is then seen as "symptomatic" of wider, more troubling but less concrete themes. It escalates up the hierarchy of responsibility and control, perhaps provoking an official enquiry or statement, which temporarily appeases the moral campaigners and dissipates the sense of panic. (221-222)

(Sociologists in particular have developed and challenged these ideas, but for my purposes here, this general approach to moral panics is accurate enough.)

There are a variety of fronts and a variety of causes being fought for in the wider culture war that includes (utilizes, benefits from) such panics as the current one (over the University of Chicago dean's letter). It is a war over the purpose and structure of higher education (and of education generally), it is a war over the meaning and implications of history, and it is a war over the meaning and implications of personal and group identities.

Kevin Gannon is onto something when he writes:

I don’t think it’s a coincidence that the backlash against so-called “political correctness” in higher education has intensified in direct variation with the diversification of the academy, areas of scholarship, and -- most significantly -- the student population. Underlying much of the hand-wringing about the state of the academy is a simple desire to have the gatekeepers remain in place.

Add to that: the challenge that

Black Lives Matter and other movements have made to the university status quo.

However, I think Gannon's argument soon falls into one of the traps this moral panic sets. Look where he goes next:

For every ginned-up hypothetical scenario of spoiled brats having a sit-in to protest too many white guys in the lit course, there are very real cases where trigger warnings or safe spaces aren’t absurdities, but pedagogical imperatives. If I’m teaching historical material that describes war crimes like mass rape, shouldn’t I disclose to my students what awaits them in these texts? If I have a student suffering from trauma due to a prior sexual assault, isn’t a timely caution the empathetic and humane thing for me to do? And what does it cost? A student may choose an alternate text I provide, but this material isn’t savagely ripped out of my course to satiate the PC police.

The trap here is the defense of "trigger warnings", because that's not

really what the letter and similar statements are about. People ought to be able to disagree about pedaogy while agreeing that the dean here overstepped his bounds. If a magic wand were waved and all the controversial issues that the letter is ostensibly about were made to disappear into unanimous agreement, the underlying questions of power would still remain.

What we need to look at are what the dean's statements are doing. If this is a moral panic, then it is trying to bring more people over "to the support of increasingly coercive measures on the part of the state" (or, in this case, university administration) and it "lends its legitimacy to a 'more than usual' exercise of control".

The letter is about control: who has it and who gets to assert it. Here, the increasingly coercive measures are not on the part of the state, but of the university administration. The letter is attempting to mandate against certain pedagogical practices and certain behaviors by student groups and individual students. The dean has asserted control. He has asserted the power to speak for the entire university.

I think it is an error to fall into the microargument over "trigger warnings", etc., because the meaningful argument is about who gets to mandate what, who gets to speak for whom, who dictates and who is dictated to. On the issue of this letter, that seems to me an argument for the University of Chicago's faculty, staff, and students to have together. But it points to a larger question of the neoliberal university.

The Neoliberal UniversityOver the last fifteen or twenty years in the United States, we've seen the triumph of a structural shift in universities, one that takes their medieval guild structure and alters it to a more corporate, neoliberal structure where all consequential decisions are the domain of the upper administration, where students become

consumers and teachers

deliver content, where one must

optimize processes and appeal to

external stakeholders and

achieve high performance to

enable success. (I think of it as the Triumph of Business School Logic.) In such a world, all value is numerical and everything can be measured with market reports. (For more on neoliberalism, I tend to refer to Philip Mirowski's

Never Let a Serious Crisis Go to Waste.)

This is not, of course, to say that individual groups, departments, or organizations within universities are themselves purveyors of neoliberal logic. Some are, some aren't. What I'm talking about when I talk about the

neoliberal university is its institutional structures and, especially, the priorities and actions of the administration, which under neoliberalism becomes (or wants to become) more powerful than in earlier structures where the faculty had more influence and control over the university as an institution. Such structures, priorities, and actions may be influenced by various groups outside the administration (the Economics Department, for instance, might have a particular influence on the administration's ideology and the College of Liberal Arts might have little to no influence. Or vice versa). But basically, the neoliberal university is the university not of colleagues and peers and truly shared governance, but of Boss Administrator.

|

| Boss Administrator |

SolidarityThere are contradictions in all this, as a recent

Harvard Magazine article on

"Title IX and the Critique of the Neoliberal University" tries to show, saying: "An obvious response to the narrative critiquing the corporatizing university might then suggest that it’s invoked to protect the interests of the faculty over those of students and other university affiliates."

Such a frame, though, relies on the idea that

the faculty, the students, and

other university affiliates have inherently different interests, and that those interests are in conflict. It seems to me that things are more complicated than that. It seems to me that such a frame is already working within the assumptions of neoliberalism. The frame hides the many areas where the different groups that constitute a university can stand in solidarity — as I think they must if we are to have any hope of building a structure for the modern university that is not neoliberal.

While recent events have highlighted faculty vs. administration, we need to find better ways not only to undo as much of that dichotomy as possible, but to also increase solidarity with students and staff. Staff in particular can get lost in the arguments, and yet at every school I'm familiar with, the staff are the people most essential to the smooth functioning of everyday life. The staff must be included in any consideration of the work of the institution.

The neoliberalization of the university depends on, encourages, and exacerbates conflicts between the interests of

the faculty, the students, and

other university affiliates. They are different groups, yes, and different groups made up of different people, yes, and as such may always be coming at the goals of the institution from different points of view, with different values and different priorities, but that shouldn't destroy the idea of the university as a coalition, a union of differences. The neoliberal university destroys solidarity.

A Personal (and Utopian) Vision of the UniversityI keep writing and rewriting this post because I keep falling into the perhaps unavoidable and perhaps academic habit of pretending to perhaps know what I'm perhaps talking about.

No, that is not what I meant. That is not it at all.

Try this:

I cannot possibly pretend to have all the answers for how to escape the many binds that wrap universities in moral panics, culture wars, neoliberalism, etc. Not just because I am not omniscient. Not just because every institution has different systems and emphases, different quirks and qualms. But because—

(And yet of course injustice is structural and systemic. Of course.)

My own life has been deeply shaped by the binds I'm (perhaps) pretending not to be all bound up in. Institutions I have devoted myself to continue to be warped and bruised (and occasionally polished) by them.

There have been some pretty deep bruises over the last year.

I can't pretend I'm not writing from anger.

I can't pretend I'm not wounded in these culture wars.

And yet somehow I have some sort of hope.

Hope for what?

I'm not sure.

Here are some incomplete thoughts on my personal values and visions for academia, because I am an academic and thus must have a list of personal values and visions for academia, mustn't I? These mostly feel obvious to me, even (embarrassingly) banal, but perhaps articulating them is worthwhile:

I value a diversity of pedagogies and a diversity of course options for students. I think students will gain the most from having available to them teachers who are devoted to the pedagogy of the most traditional of lectures and teachers who are devoted to the pedagogy of the most radical of student liberation and teachers who fall everywhere in between. No teacher is great for all students, no pedagogy is great for all students. Had I the power, I would, for instance, eliminate all requirements for syllabi and simply require that teachers be thoughtful about their pedagogy and that they enter the classroom from a basic standpoint of respect for their students as human beings and as people capable of thought.

Public education should be free and open to the public. Society at large benefits significantly from open access to education. If we can fund trillion-dollar wars, we can fund public education. We simply choose not to. One of the engines driving the neoliberalization of higher ed is the lack of funding from the public. When there isn't enough money to go around, everything gets assessed first by cost. That will destroy all the best aspects of our universities.

Students, faculty, staff, and administration need to be able to find solidarity within mutual goals (and mutual aid). A diversity of disciplines, of epistemologies, of pedagogies, of life experience, etc. makes solidarity both challenging and imperative. The question I fall back on is: What can we do to strengthen our multiplicities?

I want academia to be a refuge for us all. This idea is inevitably solipsistic, because academia has been a refuge for me. How can I find values and visions beyond my own experience? (A university that was a true refuge might be able to show me the way. I think it has sometimes. Sometimes I've been oblivious, pig-headed, scared. But sometimes I've learned other ways. Yes, sometimes.)

Finally

, I yearn for a university where curiosity is celebrated as a kind of pleasure, where knowledge is a value unto itself, and where intellectual passion is perceived as essential to the good life.But What About Trigger Warnings, Etc.?(Oh gawd, I don't want to talk about this.)

What's the issue?

Is this the issue?

This is not

the issue.

It is

an issue. As such, it should be discussed, and it should continue to be discussed, and there should be nuance to the discussion.

(Assignment: Compare the rhetoric of "trigger warnings" and "spoiler warnings".)

(Assignment:

Discuss "entitlement".

What does it mean to be entitled?

Who gets to be entitled?

Explain.)

I don't think "trigger warnings" (or, better:

content notes) should be mandated or prohibited.

I don't think there is any practical way to mandate or prohibit such things without gross violations of academic freedom for everyone involved.

I could be wrong.

I am skeptical. I am wary.

What if, as has happened recently, such proposals come from students?

I think students should propose whatever they want.

Proposals are good. They get us talking about what we value and why.

Students have a big stake in this endeavor of education.

Institutions function through discussion, compromise, experiment.

Students should be encouraged to enter the discussion.

They should be aware that there is often compromise.

They should be encouraged to experiment.

Experiments often fail.

Experiment.

Try again.

Again.

I use content notes myself occasionally when presenting students with material that is particularly graphic or intense (in my judgment) in its sexual and violent content. That just seems polite. I spend a lot of time on the first day of class describing what we'll be doing, reading, and viewing; and later, I usually describe upcoming material to students so they'll have some sense of what they're getting themselves into. But I do that with most material, even the most ordinary and least controversial. It rarely seems pedagogically useful to me for students to go into upcoming work completely ignorant of its content and/or my reason for asking them to give that work their time and attention.

(In terms of whether students have a right to have alternative material if they are concerned about the material's difficulty for reasons of their own experiences or opinions, I generally think not, because they are usually not forced into a course. I say "generally" and "usually" because there are times when requirements, schedules, and such converge to effectively force a student into a particular course, and in that case, yes, more compromise may be necessary, but such situations are rare. I think. I hope.)

Beyond the sort of content notes I use when it feels necessary, my own feelings are (sometimes; often) along the lines of

the anonymous 7 Humanities Professors who wrote an essay a few years ago for Inside Higher Ed.

Yes, I have fears. I fear chilling effects. Yes. I think chilling effects happen. I think they come from all sorts of different directions. I think they are sometimes contradictory. Much depends on individual places, individual policies, even individual people.

A lot of the rhetoric around trigger warnings, safe spaces, etc. can be turned around and used for reactionary, regressive purposes. Jack Halberstam tries to show this in

"Trigger Happy: From Content Warning to Censorship". (I know a lot of people reject Halberstam's ideas. Rejection is fine, but I think dismissal is hasty. Show your work.)

Among the points made by the 7 Humanities Professors, two key ones are:

- "Faculty of color, queer faculty, and faculty teaching in gender/sexuality studies, critical race theory, and the visual/performing arts will likely be disproportionate targets of student complaints about triggering, as the material these faculty members teach is by its nature unsettling and often feels immediate.

- "Untenured and non-tenure-track faculty will feel the least freedom to include complex, potentially disturbing materials on their syllabuses even when these materials may well serve good pedagogical aims, and will be most vulnerable to institutional censure for doing so."

The 7 Humanities Professors go on to worry that the use of trigger warnings will lead to an expectation among students of such things for any material that is even remotely potentially offensive or disturbing, and a backlash against any professor who does not provide such a warning.

I wonder, though: Does that kind of effect need to be inevitable?

(The idea of safe spaces and safe zones was important to the LGBT movement for a while. I remember the sense of comfort — good comfort, necessary comfort — I felt when I saw "Safe Zone" stickers on faculty office doors. "Okay," I would think, "I can engage with this person. They're less likely to reject my humanity." That was comfort. That was refuge. It allowed thought, conversation, and learning to start. I see those stickers less often these days, I assume because there is an assumption that they are no longer necessary, especially as more and more universities have adopted institution-wide anti-discrimination policies. Still, I smile whenever I see one of those stickers, even if it's fading, even if it's on a door no-one uses anymore. There was comfort. There was refuge.)

If there is a synthesis of my ideas here, perhaps it could be this: We must be especially careful and deliberate in what we normalize.

Most faculty are not trained psychologists or psychiatrists, nor should they pretend to be. I think pretending to be a therapist when you have no training in therapy is unethical and potentially extremely dangerous both for the faculty member and their students.

(Don't give in to the guru temptation. Kill the guru in you.)

And yet a lot of teachers are drawn to the profession for reasons that seem to lead them toward wanting to be therapists, and while (perhaps?) on a general level this might not necessarily be a harmful tendency, when teachers perceive of themselves primarily as therapists, they tread into dangerous waters. (I've seen this especially among acting teachers and creative writing teachers, but perhaps it is a common tendency elsewhere, too.) As Nick Mamatas has said,

"Those who can't be a therapist, teach." This tendency should not be encouraged. Compassion, absolutely. Pretending to be a therapist, no.

I am not a therapist. I will not pretend to be a therapist. I am a quasi-expert on certain, very narrow, types of reading and writing. That is all.

There are resources on most campuses for students in crisis, and faculty should be familiar with those resources so they can direct students to them. (If a student's issues are too great for the resources of the university to help with, it makes no sense to me for the university or student to pretend otherwise, and in such cases a university should be able to compassionately and supportively say, "This is not the right place for you. We don't have the resources to help you here." Not doing so risks harming the student more. It is fatal for universities to try to be and do everything for everyone.)

Be Careful What You OssifyFrom the

Susanne Lohmann essay that Henry Farrell links to:

The problems to which the university is a response are hard problems, and there is no free lunch. Institutional solutions are generally second-best in the sense that they constitute the best solution that is feasible in the light of environmental constraints (in which case they are a defense), or they are less than second-best (in which case they are defective).

As a necessary by-product of fulfilling their productive functions, the structures of the university have a tendency to ossify. It is precisely because the powerful incentives and protections afforded by these structures are intertwined with their potential for ossification that it is hard to disentangle where the defects of the university end and its defenses begin.

Perhaps

ossification is a better way of thinking about the ideas I've been circling around here than

normalization, or perhaps they work together.

If ossification is unavoidable, even perhaps (occasionally?) desireable, then:

Be careful what you ossify.

|

| Chagall, "The Concert" |

RefugeThe university must allow refuge.

Refuge must allow the university.

(I keep writing and rewriting this post.)

Freedom from. Freedom to.

Safety from. Safety to.

(Or just more unanswerable holes.)

All pedagogy allows some things and censures others. What does your pedagogy allow? What does it censure? How do you know?

Ripeness Is All

GLOUCESTER: No farther, sir; a man may rot even here.

EDGAR: What, in ill thoughts again? Men must endure

Their going hence, even as their coming hither;

Ripeness is all: come on.

GLOUCESTER: And that's true too.

Exeunt.

By: Lisa Kramer,

on 8/12/2016

Blog:

OUPblog

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

Books,

literacy,

Education,

India,

education policy,

pedagogy,

indian politics,

free education,

Social Sciences,

*Featured,

compulsory education,

indian education,

NFE,

R. V. Vaidyanatha Ayyar,

RTE act,

The Holy Grail: India's Quest for Universal Elementary Education,

universal elementary education,

Add a tag

Two factors contributed to the quantum leap that the idea of district planning made. First was the Total Literacy Campaign which caught the nation’s attention; the success of quite a few districts in becoming ‘totally literate’ imparted a new thrust to UPE because it was realised that that success would be ephemeral if an inadequate schooling system spawned year after year a new brood of illiterates.

The post A commemoration and a counter-revolution in the making appeared first on OUPblog.

Eric Bennett has an MFA from

Iowa, the MFA of MFAs. (He also has a Ph.D. in Lit from Harvard, so he is a man of fine and rare academic pedigree.) Bennett's recent book

Workshops of Empire: Stegner, Engle, and American Creative Writing during the Cold War is largely about the Writers' Workshop at Iowa from roughly 1945 to the early 1980s or so. It melds, often explicitly,

The Cultural Cold War with

The Program Era, adding some archival research as well as Bennett's own feeling that the work of politically committed writers such as Dreiser, Dos Passos, and Steinbeck was marginalized and forgotten by the writing workshop hegemony in favor of individualistic, apolitical writing.

I don't share Bennett's apparent taste in fiction (he seems to consider Dreiser, Dos Passos, Steinbeck, Thomas Wolfe, etc. great writers; I don't), but I sympathize with his sense of some writing workshops' powerful, narrowing effect on American fiction and publishing for at least a few decades. He notes in his conclusion that the hegemonic effect of Iowa and other prominent programs seems to have declined over the last 15 years or so, that Iowa in recent years has certainly become more open to various types of writing, and that even when Iowa's influence was at an apex, there were always other sorts of programs and writers out there — John Barth at Johns Hopkins, Robert Coover at Brown, and Donald Barthelme at the University of Texas are three he mentions, but even that list shows how narrow in other ways the writing programs were for so long: three white hetero guys with significant access to the NY publishing world.

What Bennett most convincingly shows is how the discourse of creative writing within U.S. universities from the beginning of the Cold War through at least to the 1990s created a field of limited, narrow values not only for what constitutes "good writing", but also for what constitutes "a good writer". It's a tale of parallel, and sometimes converging, aesthetics, politics, and pedagogies. Plenty of individual writers and teachers rejected or rebelled against this discourse, but for a long time it did what hegemonies do: it constructed common sense. (That common sense was not only in the workshops — at least some of it made its way out through writing handbooks, and can be seen to this day in pretty much all of the popular handbooks on how to write, including Stephen King's

On Writing.)

Some of the best material in

Workshops of Empire is not its Cold War revelations (most of which are known from previous scholarship) but in its careful limning of the tight connections between particular, now often forgotten, ideas from before the Cold War era and what became acceptable as "good writing" later. The first chapter, on the

"New Humanism", is revelatory, especially in how it draws a genealogy from

Irving Babbitt to Norman Foerster to

Paul Engle and

Wallace Stegner. Bennett tells the story of New Humanism as it relates to New Criticism and subsequently not just the development of workshop aesthetics, but of university English departments in the second half of the 20th century generally, with New Humanism adding a concern for ethical propriety ("the question of the relation of the goodness of the writing to the goodness of the writer") to New Criticism's cold formalism:

Whereas the New Criticism insisted on the irreducible and indivisible integrity of the poem or story — every word counted — the New Humanism focused its attention on the irreducible and indivisible integrity of the humanistic subject. It did so not as a kind of progressive-educational indulgence but in deference to the wholeness of the human person and accompanied by a strict sense of good conduct. (29-30)

This mix was especially appealing to the post-WWII world of anti-Communist liberalism, a world scarred by the horrors of Nazism and Stalinism, and a United States newly poised to inflict its empire of moral righteousness across the world.

For all of Bennett's gestures toward Marxism and anti-imperialism, he seems to share some basic assumptions about the power of literature with the men of the Cold War era he disdains as conservatives. In the book's conclusion, he writes:

It remains an open question just how much criticism some or all American MFA programs deserve for contributing to the impasse of neoliberalism — the collective American disinclination to think outside narrow ideological commitments that exacerbate — or at the very least preempt resistance to — the ugliest aspects of the global economy. Those narrow commitments center, above all, on an individualism, economic and otherwise, vastly more powerful in theory and public rhetoric than in fact. We encourage ourselves to believe that we matter more than we do and to go it alone more than we can. This unquestioned inflation of the personal begs, in my opinion, the kinds of questions that must be asked before any reform or solution to some seriously pressing problems looks likely to be found. (173)

This is almost comically self-important in its idea that MFA programs might (he hopes?) have enough cultural effect that if only they had been more willing to teach students to write like Thomas Wolfe and John Steinbeck, then maybe we could conquer neoliberalism! One moderately popular movie has more cultural effect than piles and piles of books written by even the famous MFA people. If you want to fight neoliberalism, your MFA and your PhD (from Harvard!) aren't likely to do anything, sorry to say. If you want to fight neoliberalism ... well, I don't know. I'm not convinced neoliberalism

can be fought, though we might be able to find

an occasional escape in aesthetics. The idea that Books Do Big Things In The World is one that Bennett shares with his subjects; he'd just prefer they read different books.

As self-justifying delusions go, I suppose there are worse, and all of us who spend our lives amidst writing and reading believe to some extent or another that it's worthwhile, or else we wouldn't do it. But "worthwhile" is far from "world-changing". (Rx: Take a couple

Wallace Shawn plays and call me in the morning.)

Despite this, Bennett's concluding chapter had me raising my fist in solidarity, because no matter what our personal tastes in fiction may be, no matter how much we may disagree about the extent to which writing can influence the world, we agree that writing pedagogy ought to be diverse and historically informed in its approach.

Bennett shows some of the forces that imposed a common shallowness:

There was, in the second wave of programs — the nearly fifty of them founded in the 1960s — little need to critique the canon and smash the icons. To the contrary, the new roster of writing programs could thrive in easy conscience. This was because each new seminar undertook to add to the canon by becoming the canon. The towering greats (Shakespeare, Milton, Whitman, Woolf, whoever) diminished in influence with each passing year, sharing ever more the icon's niche with contemporary writers. In 1945, in 1950, in 1955, prospective poets and novelists looked to the neverable pantheon as their competition. In 1980, in 1990, in 2015, they more often regarded their published teachers or peers as such. (132)

That's polemical, and as such likely hyperbolic, but it suggests some of the ways that some writing programs may have capitalized on the culture of narcissism that has only accelerated via social media and

is now ripe for economic exploitation. I don't think it's a crisis of the canon — moral panics over the Great Western Tradition are academic Trumpism — so much as a crisis of literary-historical knowledge. Aspiring writers who are uninterested in reading anything written before they were born are nincompoops. Understandably and forgiveably so, perhaps (U.S. culture is all about the current whizbang thing, and historical amnesia is central to the American project), but too much writing workshop pedagogy, at least of the recent past, has been geared toward encouraging nincompoopness. As Bennett suggests, this serves the interests of American empire while also serving the interests of the writing world. It domesticates writers and makes them good citizens of the nationalistic endeavor.

Within the context of the book, Bennett's generalizations are mostly earned. What was for me the most exciting chapter shows exactly the process of simplification and erasure he's talking about. That chapter is the final one before the conclusion: "Canonical Bedfellows: Ernest Hemingway and Henry James". Bennett's claim here is straightforward: The consensus for what makes writing "good" that held at least from the late 1940s to the end of the 20th century in typical writing workshops and the most popular writing handbooks was based on teachers' knowledge of Henry James's writing practices and everyone's veneration of Hemingway's stories and novels.

For Bennett, Hemingway became central to early creative writing pedagogy and ideology for three basic reasons: "he fused together a rebellious existential posture with a disciplined relationship to language, helping to reconcile the avant-garde impulse with the classroom", "he offered in his own writing...a set of practices with the luster of high art but the simplicity of any good heuristic", and "he contributed a fictional vision whose philosophical dimensions suited the postwar imperative to purge abstractions from literature" (144). Hemingway popularized and made accessible many of the innovations of more difficult or esoteric writers: a bit of Pound from Pound's Imagist phase, some of Stein's rhythms and diction, Sherwood Anderson's tone, some of the early Joyce's approach to word patterns... ("He was possibly the most derivative

sui generis author ever to write," Bennett says. Snap!) Hemingway's lifestyle was at least as alluring for post-WWII male writers and writing teachers as his writing style: he was macho, war-scarred, nature-besotted in a Romantic but also carnivorous way. He was no effete intellectual. If you go to school, man, go to school with Papa and you'll stay a man.

The effect was galvanizing and long-term:

Stegner believed that no "course in creative writing, whether self administered or offered by a school, could propose a better set of exercises" than this method of Hemingway's. Aspirants through to the present day have adopted Hemingway's manner on the page and in life. One can stop writing mid-sentence in order to return with momentum the following morning; aim to make one's stories the tips of icebergs; and refrain from drinking while writing but aim to drink a lot when not writing and sometimes in fact drink while writing as one suspects with good reason that Hemingway himself did, despite saying he didn't. One can cultivate a world-class bullshit detector, as Hemingway urged. One can eschew adverbs at the drop of a hat. These remain workshop mantras in the twenty-first century. (148)

Clinching the deal, the Hemingway aesthetic allowed writing to be gradeable, and thus helped workshops proliferate:

Hemingway's methods are readily hospitable to group application and communal judgment. A great challenge for the creative writing classroom is how to regulate an activity ... whose premise is the validity and importance of subjective accounts of experience. The notion of personal accuracy has to remain provisionally supreme. On what grounds does a teacher correct student choices? Hemingway offered an answer, taking prose style in a publicly comprehensible direction, one subject to analysis, judgment, and replication. ... One classmate can point to metaphors drawn from a reality too distant from the characters' worldview. Another can strike out those adverbs. (151)

Bennett then points out that the predecessors of the New Critics, the conservative Southern Agrarians, thought they'd found in Hemingway almost their ideal novelist (alas, he wasn't Southern). "The reactionary view of Hemingway," Bennett writes, "became the consensus orthodoxy." Hemingway's concrete details don't offer clear messages, and thus they allowed his work to be "universal" — and universalism was the ultimate goal not only of the Southern Agrarians, but of so many conservatives and liberals after WWII, when art and literature were seen as a means of uniting the world and thus defeating Communism and U.S. enemies. "Universal" didn't mean

actually universal in some equal exchange of ideas and beliefs — it meant imposing American ideals, expectations, and dreams across the globe. (And consequently opening up the world to American business.)

Such a discussion of how Hemingway influenced creative writing programs made me think of other ways complex writing was made appealing to broad audiences — for instance, much of what Bennett writes parallels with some of the ideas in work such as

Creating Faulkner's Reputation by Lawrence H. Schwartz and especially

William Faulkner: The Making of a Modernist, where Daniel Singal

proposes that Faulkner's alcoholism, and one alcohol-induced health crisis in November 1940 especially, turned the last 20 years of Faulkner's life and writing into not only a shadow of its former achievement, but a mirror of the (often conservative) critical consensus that built up around him through the 1940s. Faulkner became teachable, acceptable, "universal" in the eyes of even conservative critics, as well as in Faulkner's own pickled mind, which his famous

Nobel Prize banquet speech so perfectly shows.

(Thus some of my hesitation around Bennett's too easy use of the word "modernist" throughout

Workshop of Empire — the strain of Modernism he's talking about is a sanitized, domesticated, popularized, easy-listening Modernism. It's Hemingway, not Stein. It's late Faulkner, not

Absalom, Absalom!. It's white, macho-male, heterosexual, apolitical. The influence seems clear, but it chafes against my love of a broader, weirder Modernism to see it labeled only as "modernism" generally.)

Then there's Henry James. Not for the students, but the teachers:

As with Hemingway, James performed both an inner and an outer function for the discipline. In his prefaces and other essays, he established theories of modern fiction that legitimated its status as a discipline worthy of the university. Yet in his powers of parsing reality infinitesimally, James became an emblem similar to Hemingway, a practitioner of resolutely anti-Marxian fiction in an era starved for the same. (152)

Reducing the influence and appeal here to simply the anti-Marxian is a tic produced by Bennett's yearning for the return of the Popular Front, because his own evidence shows that the immense influence of Hemingway and James served not only to veer teachers, students, writers, and critics away from any whiff of agit-prop, but that it created an aesthetic not only hostile to Upton Sinclair but to the 19th century Decadents and Symbolists, to much of the Harlem Rennaissance, to most forms of popular literature, and to any writers who might seem too difficult, abstruse, or weird (imagine Samuel Beckett in a typical writing workshop!).

As Bennett makes clear, the

idea of Henry James's writing practice more than any of James's actual texts is what held through the decades. "He did at least five things for the discipline," Bennett says (152-153):

- His Prefaces assert the supremacy of the author, and "the early MFA programs depended above all on a faith that literary meaning could be stable and stabilized; that the author controlled the literary text, guaranteed its significance, and mastered the reader."

- James's approach was one of research and selection, which is highly appealing to research universities. Writing becomes a laboratory, the writer an experimenter who experiments succeed when the proper elements are selected and balanced. "He identified 'selection' as the major undertaking of the artist and perceived in the world a landscape without boundaries from which to do the selecting." Revision is key to the experiment, and revision should be limitless. Revision is virtue.

- James was anti-Romantic in a particular way: "James centered modern fiction on art rather than the artist, helping to shape the doctrines of impersonality so important to criticism from the 1920s through the 1950s. He insulated the aesthetic object from the deleterious encroachments of ego." Thus the object can be critiqued in the workshop, not the creator.

- "James nonetheless kept alive the romantic spirit of creative inspiration and drew a line between those who have it and those who don't." He often sounds mystical in his Prefaces (less so his Notebooks). The craft of writing can be taught, but the art of writing is the realm of genius.

- "James regarded writing as a profession and theorized it as one." The writer is someone who labors over material, and the integrity of the writer is equal to the integrity of the process, which leads to the integrity of the final text.

These ideas took hold and were replicated, passed down not only through workshops, but through numerous handbooks written for aspiring writers.

The effect, ultimately, Bennett asserts, was to stigmatize intellect. Writing must not be a process of thought, but a process of feeling. It must be sensory. "No ideas but in things!" A convenient ideology for times of political turmoil, certainly.

Semester after semester, handbook after handbook, professor after professor, the workshops were where, in the university, the senses were given pride of place, and this began as an ideological imperative. The emphasis on particularity, which remains ubiquitous today, inviolable as common sense, was a matter for debate as recently as 1935. The debate, in the 21st century, is largely over. (171)

I wonder. From writers and students I sense — and this is anecdotal, personal, sensory! — a desire for something more than the old Imagist ways. A desire for thought in fiction. For politics, but not a simple politics of vulgar Marxism. The ubiquity of dystopian fiction signals some of that, perhaps. Dystopian fiction is being written by both the hackiest of hacks and the highest of high lit folks. It shows a desire for imagination, but a particular sort of imagination: an imagination about society. Even at its most

personal, navel-gazing, comforting, and self-justifying, it's still at least trying to wrestle with more than the concrete, more than the story-iceberg.

So, too, the efflorescence of different types of writing programs and different types of teachers throughout the U.S. today suggests that the era of the aesthetic Bennett describes may be, if not over, at least far less hegemonic. Bennett cites its apex as somewhere around 1985, and that seems right to me. (I might bump it to 1988: the last full year of Reagan's presidency and the publication of Raymond Carver's selected stories,

Where I'm Calling From.) The people who graduated from the prestigious programs then went on to become the administrators later, but at this point most of them have retired or are close to retirement. There are still

narrow aesthetics, but there's plenty else going on. Most importantly, writers with quite different backgrounds from the old guard are becoming not just the teachers, but the administrators. Bennett notes that some of the criticism he received for

earlier versions of his ideas pointed to these changes:

I was especially convinced by the testimony of those who argued that the Iowa Writers' Workshop under Lan Samantha Chang's directorship has different from Frank Conroy's iteration of that program, which I attended in the late 1990s and whose atmosphere planted in my heart the suspicion that, for some reason, the field of artistic possibilities was being narrowed exactly where it should be broadest. In the twenty-first century, things have changed both at Iowa and at the many programs beyond Iowa, where few or none of my conclusions might have pertained in the first place. (163)

That's an important caveat there. The present is not the past, but the past contributed to the present, and it's a past that we're only now starting to recover.

There's much more to be investigated, as I'm sure Bennett knows. The role of the

Bread Loaf Writers' Conference and similar institutions would add some more detail to the study; similarly, I think someone needs to write about the intersections of creative writing programs and composition/rhetoric programs in the second half of the twentieth century. (Much more needs to be written about CUNY during

Mina Shaughnessy's time there, for instance, or about

Teachers & Writers.) But the value of Bennett's book is that it shows us that many of the ideas about what makes writing (and writers) "good" can be — should be — historicized. Such ideas aren't timeless and universal, and they didn't come from nowhere. Bennett provides a map to some of the wheres from whence they came.

Earlier this month, just back from a marvelous and productive

MLA Convention in Austin, Texas, I started to write a post in response to an Inside Higher Ed article on

"Selling the English Major", which discusses ways English departments are dealing with the national decline in enrollments in the major. I had ideas about the importance of senior faculty teaching intro courses (including First-Year Composition), the value of getting out of the department now and then, the pragmatic usefulness of making general education courses in the major more topical and appealing, etc.

After writing thousands of words, I realized none of my ideas, many of which are simply derived from things I've observed schools doing, would make much of a difference. There are deeper, systemic problems, problems of culture and history and administration, problems that simply can't be dealt with at the department level. Certainly, at the department level people can be experts at shooting themselves in the foot, but more commonly what I see are pretty good departments having their resources slashed and transferred to science and business departments, and then those pretty good departments are told to do better with less. (And often they do, which only increases the problem, because if they can do so well with half of what they had before, surely they could stand a few more cuts...) I got through thousands of words about all this and then just dissolved into despair.

Then I read a fascinating post from Roger Whitson:

"English as a Division Rather than a Department". It's not really about the idea of increasing enrollment in English programs, though I think some of the suggestions would help with that, but rather with more fundamental questions of what, exactly, this whole discipline even

is. Those are questions I find more exciting than dispiriting, so here are some thoughts on it all, offered with the proviso that these are quick reactions to Whitson's piece and likely have all sorts of holes in them...

The idea of creating a large division and separating it into departments is not one I support, because I think English departments ought to be more, not less, unified, but it nonetheless provides a template for thinking beyond where we are. (I don't think Whitson or Aaron Kashtan, whose proposal on Facebook Whitson built off of, desires a less unified discipline. But without clear mechanisms for encouraging, requiring, and funding interdisciplinarity, the divisions will divide, not multiply.)

The quoted Facebook post in Whitson's piece basically describes the English department at my university, and each of those pieces (literature, composition, linguistics, ESL, English education, creative writing) has some autonomy, more or less. I'm not actually convinced that that autonomy has been entirely healthy, because it's led to resource wars and has discouraged interdisciplinary work (with each little group stuck talking to each other and not talking enough beyond their own area because there's little administrative support for it and, indeed, quite the opposite: the balkanization has, if anything, increased the bureaucracy and given people more busy-work).

English departments need to seek out opportunities for unity and collaboration. I don't see how dividing things even more than they already are would achieve that, unless frequent collaboration were somehow mandated — for instance, one of the best things about

the program I attended for my master's degree at Dartmouth was that it required us to take some team-taught courses, which allowed fascinating interdisciplinary conversations and work. They could do that because they were Dartmouth and had the money to let lots of faculty collaborate. Few schools are willing to budget that way; indeed, at many places the movement is in the other direction: more students taught by fewer faculty.

Nonetheless, though I am skeptical of separating English departments more than they already are, I like some of Whitson's proposals for ways to reconfigure the idea of what we do and who we are and could be. Even the simple act of using these ideas as jumping-off points for (utopian) conversation is useful.

PlanetarityHere's a key point from Whitson: "I propose asking for more diverse hires by illustrating how important marginalized discourses are to the fields we study, while also investing heavily in opportunities for new interdisciplinary collectives and collaborations." (Utopian, but we're here for utopian discussion, not the practicalities of convincing the Powers That Be of the value of such an iconoclastic, and likely expensive, approach...)

This connects to a lot of conversations I observed or was part of at MLA, particularly among people in the Global Anglophone

Forum (where nobody seems to like the term "global anglophone"). Discussions of the

difficulties for scholars of work outside the US/Britosphere were common. At least on the evidence of job ads, it seems departments are, overall, consolidating away from such areas as postcolonial studies and toward broader, more general, and often more US/UK-centric curriculums. The center is reasserting itself curricularly, defining margins as extensions, roping them into its self-conception and nationalistic self-justification. The effect of austerity on humanities departments has been devasting for diversity of any sort.

I like the idea of "Reading and Writing Planetary Englishes" as a replacement for English Lit, ESL, and parts of Rhet/Comp. Heck, I like it as a replacement for English departments generally. It's not perfect, but nothing is, and "English" is such a boring, imposing term for our discipline...

(Where Comparative Literature — "Reading and Writing Planetary Not-Englishes" — fits within that, I don't know, and it's a question mostly unaddressed in Whitson's post and will remain unaddressed here because questions of literature in translation and literature in languages other than English are too big for what I'm up to at the moment. They are necessary questions, however.)

Spivak's idea of "planetarity" ("rather," as she says, "than continental, global, or worldly" [

Death of a Discipline 72]) is well worth debating, and may be especially appealing in these days of seemingly endless discussion of "the anthropocene" — but what exactly "planetarity" means to Spivak is not easy to pin down. (She can be an infuriatingly vague writer.) Here's one of the most concrete statements on it from

Death of a Discipline:

If we imagine ourselves as planetary subjects rather than global agents, planetary creatures rather than global entities, alterity remains underived from us; it is not our dialectical negation, it contains us as much as it flings us away. And thus to think of it is already to transgress, for, in spite of our forays into what we metaphorize, differently, as outer and inner space, what is above and beyond our own reach is not continuous with us as it is not, indeed, specifically discontinuous. We must persistently educate ourselves into this peculiar mindset. (73)

A more comprehensible statement on planetarity appears in Chapter 21 of

An Aesthetic Education in the Era of Globalization, "World Systems and the Creole":

The experimental musician Laurie Anderson, when asked why she chose to be artist-in-residence at the National Aeronautic and Space Administration, put it this way: "I like the scale of space. I like thinkng about human beings and what worms are. We are really worms and specks. I find a certain comfort in that."

She has put it rather aggressively. That is not my intellectual style, but my point is close to hers. You see how very different it is from a sense of being the custodians of our very own planet, for god or for nature, although I have no objection to such a sense of accountability, where our own home is our other, as in self and world. But that is not the planetarity I was talking about. (451)

On the next page, she makes a useful statement: "We cannot read if we do not make a serious linguistic effort to enter the epistemic structures presupposed by a text." (Technically, yes, we

can read [decode dictionary meanings of words] without such effort, but whatever understanding we come to will be narcissistic, solipsistic.)

And then on p.453: "...I have learned the hard way how dangerous it is to confuse the limits of one's knowledge with the limits of what can be known, a common problem in the academy."

Spivak (here and elsewhere) exhorts us to give up on totalizing ideas. She quotes Édouard Glissant on the infinite knowledge necessary to understand cultural histories and interactions: "No matter," Glissant says, "how many studies and references we accumulate (though it is our profession to carry out such things properly), we will never reach the end of such a volume; knowing this in advance makes it possible for us to dwell there. Not knowing the totality does not constitute a weakness."

That could be another motto for our new approach: "Not knowing the totality does not constitute a weakness."

What can be known, then, if not a totality, a thing to be mastered? Our limitations.

What I personally like about transnational, global, planetary, etc. approaches is that their impossibility is obvious and any pretense toward totalized knowledge is going to be laughed at, as it should be.

One point Whitson makes that I disagree with, or at least disagree with the phrasing of, is: "Most undergraduate students in English do not have a good grasp of rhetorical devices (

kairos, chaismus, prosopopoeia) and these would replace 'close reading' (a term that lacks the specificity of the more developed rhetorical tradition) in student learning outcomes and primary classes."

Reading is more than rhetorical analysis. "Close reading" may have a bad reputation, and in some of the ways it's used it deserves that bad reputation, but it remains a useful term for a necessary skill. Especially as we think about ways of communicating what we do to audiences skeptical of the humanities generally, a term like "close reading", which can be understood by people who aren't specialists, seems to me less alienating, and less likely to produce misunderstandings, than "rhetoric". But that may just be my own dislike of the word "rhetoric" and my general feeling that rhetorical analysis is, frankly, dull. (There's a reason I'm not a rhet/comp PhD, despite being at a great school for it.) I wouldn't pull a Whitson and say "We must have no rhetorical analysis and only close reading!" That's silly. There are plenty of reasons to teach rhetorical analysis in introductory and advanced forms. There are also many good reasons to teach and encourage close reading. Making it into an opposition and a zero sum game is counterproductive. After all, rhetorical analysis requires close reading and some close reading requires rhetorical analysis.

In any case, instead of debating rhetorical analysis vs. close reading vs. whatever, what I think we ought to be looking at first is the seemingly simple activity of making meaning from what we read. That unites a lot of approaches with productive questions. (John Ciardi's title

How Does a Poem Mean? has been a guiding, and fruitful, principle of my own reading for a long time.) From there, we can then begin to talk about

interpretive communities, systems of textual analysis, etc: ways of reading, and ways of making sense of texts. Certainly, that includes methods of argument and persuasion. But also much more.

There's much to learn from the field of rhetoric and composition on all that. (In fact, a term from rhet/comp,

discourse communities, can be quite useful here if applied both to the act of reading and the act of writing.) Reading should not — cannot — be the province only of literary scholars. A

recent issue of Pedagogy offers some fascinating articles on teaching reading from a comp/rhet point of view. Further, coming back to Spivak, it seems to me that her work, for all its interdisciplinarity, frequently demonstrates ways that readers have been led astray by not reading closely enough, and her own best work is often in her close readings of texts.

Whitson proceeds to a utopian idea of planetarity (one inherent in Spivak) as a way of broadening ideas of literature beyond the human. This would certainly make room for eco-critics, anthropocene-ists, animal studies folks, etc. This isn't my own interest, and I will admit to quite a lot of skepticism about broadening the idea of "literature" so much that it becomes meaningless, but it's clear that we need such a space within English departments, even for people who think plants write lit. Our departments ought to contain multitudes.

MediaI've taught media courses, and obviously have an interest in, particularly,

cinema. I don't think most such studies belong in English departments, so I am inclined to like the idea of it as a separate department within a general division. While there are plenty of English teachers who teach film and media well, and as an academic field it has some of its origins there, cinema especially seems to me to need people who have significant understanding of visual and dramatic arts. (Just as "new media" [now getting old] folks probably need some understanding of basic computer science.)

Media studies is inherently a site of interdisciplinary work, and that's a good thing. Working side-by-side, people who are trained in visual arts, theatre arts, technologies, etc. can produce new ways of knowing the world.

Something that media studies can do especially well is mix practitioners and analysts. Academia really likes to separate the "practical" people from the "theory" people. This is an unfortunate separation, one that has been detrimental to English departments especially, as literary scholars and writers are too often suspicious of each other. (I'll spare you my rant about how being both a literary scholar and a creative writer is unthinkable in conventional academic English department discourse. Another time.) You'll learn a lot about understanding cinema by taking a film editing class, just as you'll learn a lot about understanding literature by taking a creative writing class. Indeed, I often think the benefit of writing workshops (and their ilk) is not in how they produce better writers, but in how they may enable better readers.

On the other hand, and to argue in some ways against myself, writing and reading teachers ought to be well versed in media, because media mediates our lives and thoughts and reading and writing. To what extent should a department of reading and writing be focused on media, I don't know. Media tends to take over. It's flashy and attracts students. But one thing I fear losing is the

refuge of the English department — the one place where we can escape the flash and fizz of techno-everything, where we can sit and think about a sentence written on an old piece of paper for a while.

EducationI'm less convinced by Whitson's arguments about a division of "Composition Pedagogy and English Education". Why put Composition with English Education and not put some literary study there? Is literary study inherent in "English Education"? Why separate Composition, though? Why not call it "Teaching Reading and Writing"? Perhaps I just misunderstand the goals with this one.

It seems to me that English Education should be some sort of meta-discipline. It doesn't make much sense as a department unto itself in the scheme Whitson sets up, or most schemes, for that matter. Any sort of educational field is very difficult to set up well because it requires students not only to learn the material of their area, but to learn then how to teach that material effectively.

To me, it makes more sense to spread discussion of pedagogy throughout all departments, because one way to learn things is to try to teach them. Ideas about education, and practice at teaching, shouldn't be limited only to people who plan to become teachers, though they may need more intensive training in it.

If we want to be radical about how we restructure the discipline, integrating English Education more fully into the discipline as a whole, rather than separating it out, would be the way to go.

WritingWhitson proposes merging creative and professional writing as one department in the division. This is an interesting idea, but I'm not convinced. Again, my own prejudices are at play: in my heart of hearts, I don't think undergraduates should major in writing. I think there should be writing courses, and there should be lots of writers employed by English departments, but the separation of writing and reading is disastrous at the undergraduate level, leading to too many writers who haven't read nearly enough and don't know how to read anything outside of their narrow, personal comfort zone.

In the late '90s, Tony Kushner scandalized the Association of Theatre in Higher Education's annual conference with

a keynote speech in which he (modestly) proposed that all undergraduate arts majors be abolished. (It was published in the January 1998 issue of

American Theatre magazine.) It's one of my favorite things Kushner has ever written. The whole thing is worth reading, but here's a taste:

And even if your students can tell you what iambic pentameter is and can tell you why anyone who ever sets foot on any stage in the known universe should know the answer to that and should be able to scan a line of pentameter in their sleep, how many think that "materialism" means that you own too many clothes, and "idealism" means that you volunteer to work in a soup kitchen? And why should we care? When I first started teaching at NYU, I also did a class at Columbia College, and none of my students, graduate or undergraduate (and almost all the graduate students were undergraduate arts majors--and for the past 10 years Columbia has had undergraduate arts majors), none of them, at NYU or Columbia, knew what I might mean by the idealism/materialism split in Western thought. I was so alarmed that I called a philosophy teacher friend of mine to ask her if something had happened while I was off in rehearsal, if the idealism/materialism split had become passe. She responded that it had been deconstructed, of course, but it's still useful, especially for any sort of political philosophy. By not having even a nodding acquaintance with the tradition I refer to, I submit that my students are incapable of really understanding anything written for the stage in the West, and for that matter in much of the rest of the world, just as they are incapable of reading Plato, Aristotle, Hegel, Marx, Kristeva, Judith Butler, and a huge amount of literature and poetry. They have, in essence, been excluded from some of the best their civilization has produced, and are terribly susceptible, I would submit, to the worst it has to offer.

What I would hope you might consider doing is tricking your undergraduate arts major students. Let them think they've arrived for vocational training and then pull a switcheroo. Instead of doing improv rehearsals, make them read The Death of Ivan Illych and find some reason why this was necessary in learning improv. They're gullible and adoring; they'll believe you. And then at least you'll know that when you die and go to the judgment seat you can say "But I made 20 kids read Tolstoy!" and this, I believe, will count much to your credit. And if you are anything like me, you'll need all the credits you can cadge together.

Call it the pedagogy of pulling a switcheroo. A good pedagogy, at least sometimes. It doesn't have to be, indeed should not be, limited to Western classics, as Kushner (inadvertently?) implies, and the program he calls for would not be so limited, because the kinds of conversations that he wants students to be able to recognize and join are ones that inevitably became (if they weren't already) transnational, global, even maybe a bit planetary.

So yes, if

I were emperor of universities, I'd abolish undergraduate arts majors, but keep lots of artists as undergraduate teachers. I'd also let the artists teach whatever the heck they wanted. Plenty of writers would be better off teaching innovative classes that aren't the gazillionth writing workshop of their career. Boxing writers into teaching only writing classes is a pernicious practice, one that perpetuates the idea that the creation of literature and the study of literature are separate activities.

But let's come back to Whitson's first proposal: planetarity and the making of textual meaning.

My own inclination is not to separate so much, but to seek out more unities. What unites us? That we study and practice ways of reading and ways of writing. We should encourage more reading in writing classes and more varied types of writing in reading classes. We should toss out our inherited, traditional nationalisms and look at other ways that texts flow around us and around not-us. (Writers do. What good writer was only influenced by texts from one nation?) We should seek out the limits of our knowledge, admit them, challenge them, celebrate them.

Imagination Perhaps what we should think about is imagination. We need more imagination, and we need to educate and promote imagination. So many of the problems of our world stem from failures of imagination — from the

fear of imagination. If you want to be a radical educator, be an educator who inspires students to imagine in better, fuller, deeper ways. The conservative forces of culture and society promote exactly the opposite, because the desire of the status quo is to produce unimaginative (unquestioning, obedient) subjects.

English departments, like arts departments and philosophy departments, are marvelously positioned to encourage imagination. Any student who enters an English class should leave with an expanded imagination. Any student who studies to become an English teacher should be trained in the training of imaginations. We should all be advocates for imagination, activists for its value, its necessity.

One of the best classes I've ever taught was called Writing and the Creative Process. (You can find links to a couple of the syllabi on my

teaching page, though they can't really give a sense of what made the courses work well.) It was a continuously successful course in spite of me. The stakes were low, because it was an introductory course, and yet the learning we all did was sometimes life-changing. This was not my fault, but the fault of having stumbled into a pedagogy that gave itself over entirely to the practice of creativity, which is to say the practice of imagination. Because it was a pre-Creative Writing class, the focus wasn't even on

becoming better writers but rather on

becoming more creative (imaginative) people. That was the key to the success. Becoming a better writer is a nice goal, but becoming a more creative/imaginative person is a vital goal. Were I titling it, I'd have called that course Writing and Creative Process

es, because one of the things I seek to help the students understand is that there is no one process for either writing or for thinking creatively. But no matter. Just by having to think about, talk about, and practice creativity a couple times a week, we made our lives better. I say

we, because I learned as much by teaching that class as the students did; maybe more.

English departments should become departments of writing, reading, and thinking with creative processes.

I began with Spivak, so I'll come back to her, this time from her recent book

Readings:

And today I am insisting that all teachers, including literary criticism teachers, are activists of the imagination. It is not a question of just producing correct descriptions, which should of course be produced, but which can always be disproved; otherwise nobody can write dissertations. There must be, at the same time, the sense of how to train the imagination, so that it can become something other than Narcissus waiting to see his own powerful image in the eyes of the other. (54)

Training — encouraging, energizing — the imagination means a training in aesthetics, in techniques of structure, in ways of valuing form, in how we find and recognize and respond to the beautiful and sublime.

I'm persuaded by Steve Shaviro's arguments in

No Speed Limit about aesthetics as something at least unassimilable by neoliberalism (if not in direct resistance to it): "When I find something to be beautiful, I am 'indifferent' to any uses that thing might have; I am even indifferent to whether the thing in question actually exists or not. This is why aesthetic sensation is the one realm of existence that is not reducible to political economy." (That's just a little sample. See

"Accelerationist Aesthetics" for more elaboration, and the book for the full argument.)

Because the realm of the aesthetic has some ability to sit outside neoliberalism, it is in many ways the most radical realm we can submit ourselves to in the contemporary world, where neoliberalism assimilates so much else.

But training the imagination is not only an aesthetic education, it's also epistemological. Spivak again:

An epistemological performance is how you construct yourself, or anything, as an object of knowledge. I have been consistently asking you to rethink literature as an object of knowledge, as an instrument of imaginative activism. In Capital, Volume 1 (1867), for example, Marx was asking the worker to rethink him/herself, not as a victim of capitalism but as an "agent of production". That is training the imagination in epistemological performance. This is why Gramsci calls Marx's project "epistemological". It is not only epistemological, of course. Epistemological performance is something without which nothing will happen. That does not mean you stop there. Yet, without a training for this kind of shift, nothing survives. (Readings 79-80)

If we're seeking, as Whitson calls us to, to create more diverse (and imaginative) departments of English, then perhaps we can do so by thinking about ways of approaching aesthetics and epistemology. We can be agents of imagination. We don't need nationalisms for that, and we don't need to strengthen divisive organizational structures that have riven many an English department.

We can — we must — imagine better.

A writer recently wrote a blog post about how he's quitting teaching writing. I'm not going to link to it because though it made me want to write this post of my own, I'm not planning either to praise or disparage the post or its author, whom I don't know and whose work I haven't read (though I've heard good things about it). Reading the post, I was simply struck by how different his experience is from my own experience, and I wondered why, and I began to think about what I value in teaching writing, and why I've been doing it in one form or another — mostly to students without much background or interest in writing — for almost twenty years.

I don't know where the quitting teacher works or the circumstances, other than that he was working as an adjunct professor, as I did for five years, and was teaching introductory level classes, as I continue to do now that I'm a PhD student. (And in some ways did back when I was a high school teacher, if we want to consider high school classes as introductory to college.) So, again, this is not about him, because I know nothing about his students' backgrounds, his institution's expectations or requirements, his training, etc. If he doesn't like teaching writing where he's currently employed, he shouldn't do it, for his own sake and for that of his students. It's certainly nothing you're going to get rich from, so really, you're doing no-one any good by staying in a job like that, and you may be doing harm (to yourself and others).

Most of the quitting teacher's complaints boil down to, "I don't like teaching unmotivated students." So it goes. There are, though, lots of different levels of "unmotivated". Flat-out resistant and recalcitrant are the ultimate in unmotivated, and I also really find no joy in working with such students, because I'm not very good at it. I've done it, but have not stayed with jobs where that felt like all there was. One year at a particular high school felt like facing nothing but 100 resistant and recalcitrant students every single day, and though the job paid quite well (and, for reasons I can't fathom, the administration wanted me to stay), I fled quickly. I was useless to most of those students and they were sending me toward a nervous breakdown. I've seen people who work miracles with such students. I wasn't the right person for that job.

But then there are the students who, for whatever reason, just haven't bought in to what you're up to. It's not their thing. I don't blame them. Put me in a math or science class, and that's me. Heck, put me in a Medieval lit class and that's me. But again and again, talented teachers have welcomed me into their world, and because of those teachers, I've been able to find a way to care and to learn about things I didn't initially care about in the least. That's the sort of teacher I aspire to be, and occasionally, for all my fumbling, seem to have succeeded at being.

It's nice to teach courses where everybody arrives on Day 1 with passion for the subject. I've taught such classes a few times. It can be fun. It's certainly more immediately fulfilling than the more common sort of classes where the students are a bit less instrinsically motivated to be there. But I honestly don't care about those advanced/magical classes as much. Such students are going to be fine with or without me. At a teaching seminar I attended 15 years ago, the instructor described such students as the ones for whom it doesn't matter if you're a person or a stalk of asparagus, because they'll do well no matter what. I don't aspire to be a stalk of asparagus.