Earlier this month, just back from a marvelous and productive MLA Convention in Austin, Texas, I started to write a post in response to an Inside Higher Ed article on "Selling the English Major", which discusses ways English departments are dealing with the national decline in enrollments in the major. I had ideas about the importance of senior faculty teaching intro courses (including First-Year Composition), the value of getting out of the department now and then, the pragmatic usefulness of making general education courses in the major more topical and appealing, etc.

After writing thousands of words, I realized none of my ideas, many of which are simply derived from things I've observed schools doing, would make much of a difference. There are deeper, systemic problems, problems of culture and history and administration, problems that simply can't be dealt with at the department level. Certainly, at the department level people can be experts at shooting themselves in the foot, but more commonly what I see are pretty good departments having their resources slashed and transferred to science and business departments, and then those pretty good departments are told to do better with less. (And often they do, which only increases the problem, because if they can do so well with half of what they had before, surely they could stand a few more cuts...) I got through thousands of words about all this and then just dissolved into despair.

Then I read a fascinating post from Roger Whitson: "English as a Division Rather than a Department". It's not really about the idea of increasing enrollment in English programs, though I think some of the suggestions would help with that, but rather with more fundamental questions of what, exactly, this whole discipline even is. Those are questions I find more exciting than dispiriting, so here are some thoughts on it all, offered with the proviso that these are quick reactions to Whitson's piece and likely have all sorts of holes in them...

The idea of creating a large division and separating it into departments is not one I support, because I think English departments ought to be more, not less, unified, but it nonetheless provides a template for thinking beyond where we are. (I don't think Whitson or Aaron Kashtan, whose proposal on Facebook Whitson built off of, desires a less unified discipline. But without clear mechanisms for encouraging, requiring, and funding interdisciplinarity, the divisions will divide, not multiply.)

The quoted Facebook post in Whitson's piece basically describes the English department at my university, and each of those pieces (literature, composition, linguistics, ESL, English education, creative writing) has some autonomy, more or less. I'm not actually convinced that that autonomy has been entirely healthy, because it's led to resource wars and has discouraged interdisciplinary work (with each little group stuck talking to each other and not talking enough beyond their own area because there's little administrative support for it and, indeed, quite the opposite: the balkanization has, if anything, increased the bureaucracy and given people more busy-work).

English departments need to seek out opportunities for unity and collaboration. I don't see how dividing things even more than they already are would achieve that, unless frequent collaboration were somehow mandated — for instance, one of the best things about the program I attended for my master's degree at Dartmouth was that it required us to take some team-taught courses, which allowed fascinating interdisciplinary conversations and work. They could do that because they were Dartmouth and had the money to let lots of faculty collaborate. Few schools are willing to budget that way; indeed, at many places the movement is in the other direction: more students taught by fewer faculty.

Nonetheless, though I am skeptical of separating English departments more than they already are, I like some of Whitson's proposals for ways to reconfigure the idea of what we do and who we are and could be. Even the simple act of using these ideas as jumping-off points for (utopian) conversation is useful.

Planetarity

Here's a key point from Whitson: "I propose asking for more diverse hires by illustrating how important marginalized discourses are to the fields we study, while also investing heavily in opportunities for new interdisciplinary collectives and collaborations." (Utopian, but we're here for utopian discussion, not the practicalities of convincing the Powers That Be of the value of such an iconoclastic, and likely expensive, approach...)

This connects to a lot of conversations I observed or was part of at MLA, particularly among people in the Global Anglophone Forum (where nobody seems to like the term "global anglophone"). Discussions of the difficulties for scholars of work outside the US/Britosphere were common. At least on the evidence of job ads, it seems departments are, overall, consolidating away from such areas as postcolonial studies and toward broader, more general, and often more US/UK-centric curriculums. The center is reasserting itself curricularly, defining margins as extensions, roping them into its self-conception and nationalistic self-justification. The effect of austerity on humanities departments has been devasting for diversity of any sort.

I like the idea of "Reading and Writing Planetary Englishes" as a replacement for English Lit, ESL, and parts of Rhet/Comp. Heck, I like it as a replacement for English departments generally. It's not perfect, but nothing is, and "English" is such a boring, imposing term for our discipline...

(Where Comparative Literature — "Reading and Writing Planetary Not-Englishes" — fits within that, I don't know, and it's a question mostly unaddressed in Whitson's post and will remain unaddressed here because questions of literature in translation and literature in languages other than English are too big for what I'm up to at the moment. They are necessary questions, however.)

Spivak's idea of "planetarity" ("rather," as she says, "than continental, global, or worldly" [Death of a Discipline 72]) is well worth debating, and may be especially appealing in these days of seemingly endless discussion of "the anthropocene" — but what exactly "planetarity" means to Spivak is not easy to pin down. (She can be an infuriatingly vague writer.) Here's one of the most concrete statements on it from Death of a Discipline:

If we imagine ourselves as planetary subjects rather than global agents, planetary creatures rather than global entities, alterity remains underived from us; it is not our dialectical negation, it contains us as much as it flings us away. And thus to think of it is already to transgress, for, in spite of our forays into what we metaphorize, differently, as outer and inner space, what is above and beyond our own reach is not continuous with us as it is not, indeed, specifically discontinuous. We must persistently educate ourselves into this peculiar mindset. (73)A more comprehensible statement on planetarity appears in Chapter 21 of An Aesthetic Education in the Era of Globalization, "World Systems and the Creole":

The experimental musician Laurie Anderson, when asked why she chose to be artist-in-residence at the National Aeronautic and Space Administration, put it this way: "I like the scale of space. I like thinkng about human beings and what worms are. We are really worms and specks. I find a certain comfort in that."On the next page, she makes a useful statement: "We cannot read if we do not make a serious linguistic effort to enter the epistemic structures presupposed by a text." (Technically, yes, we can read [decode dictionary meanings of words] without such effort, but whatever understanding we come to will be narcissistic, solipsistic.)

She has put it rather aggressively. That is not my intellectual style, but my point is close to hers. You see how very different it is from a sense of being the custodians of our very own planet, for god or for nature, although I have no objection to such a sense of accountability, where our own home is our other, as in self and world. But that is not the planetarity I was talking about. (451)

And then on p.453: "...I have learned the hard way how dangerous it is to confuse the limits of one's knowledge with the limits of what can be known, a common problem in the academy."

Spivak (here and elsewhere) exhorts us to give up on totalizing ideas. She quotes Édouard Glissant on the infinite knowledge necessary to understand cultural histories and interactions: "No matter," Glissant says, "how many studies and references we accumulate (though it is our profession to carry out such things properly), we will never reach the end of such a volume; knowing this in advance makes it possible for us to dwell there. Not knowing the totality does not constitute a weakness."

That could be another motto for our new approach: "Not knowing the totality does not constitute a weakness."

What can be known, then, if not a totality, a thing to be mastered? Our limitations.

What I personally like about transnational, global, planetary, etc. approaches is that their impossibility is obvious and any pretense toward totalized knowledge is going to be laughed at, as it should be.

One point Whitson makes that I disagree with, or at least disagree with the phrasing of, is: "Most undergraduate students in English do not have a good grasp of rhetorical devices (kairos, chaismus, prosopopoeia) and these would replace 'close reading' (a term that lacks the specificity of the more developed rhetorical tradition) in student learning outcomes and primary classes."

Reading is more than rhetorical analysis. "Close reading" may have a bad reputation, and in some of the ways it's used it deserves that bad reputation, but it remains a useful term for a necessary skill. Especially as we think about ways of communicating what we do to audiences skeptical of the humanities generally, a term like "close reading", which can be understood by people who aren't specialists, seems to me less alienating, and less likely to produce misunderstandings, than "rhetoric". But that may just be my own dislike of the word "rhetoric" and my general feeling that rhetorical analysis is, frankly, dull. (There's a reason I'm not a rhet/comp PhD, despite being at a great school for it.) I wouldn't pull a Whitson and say "We must have no rhetorical analysis and only close reading!" That's silly. There are plenty of reasons to teach rhetorical analysis in introductory and advanced forms. There are also many good reasons to teach and encourage close reading. Making it into an opposition and a zero sum game is counterproductive. After all, rhetorical analysis requires close reading and some close reading requires rhetorical analysis.

In any case, instead of debating rhetorical analysis vs. close reading vs. whatever, what I think we ought to be looking at first is the seemingly simple activity of making meaning from what we read. That unites a lot of approaches with productive questions. (John Ciardi's title How Does a Poem Mean? has been a guiding, and fruitful, principle of my own reading for a long time.) From there, we can then begin to talk about interpretive communities, systems of textual analysis, etc: ways of reading, and ways of making sense of texts. Certainly, that includes methods of argument and persuasion. But also much more.

There's much to learn from the field of rhetoric and composition on all that. (In fact, a term from rhet/comp, discourse communities, can be quite useful here if applied both to the act of reading and the act of writing.) Reading should not — cannot — be the province only of literary scholars. A recent issue of Pedagogy offers some fascinating articles on teaching reading from a comp/rhet point of view. Further, coming back to Spivak, it seems to me that her work, for all its interdisciplinarity, frequently demonstrates ways that readers have been led astray by not reading closely enough, and her own best work is often in her close readings of texts.

Whitson proceeds to a utopian idea of planetarity (one inherent in Spivak) as a way of broadening ideas of literature beyond the human. This would certainly make room for eco-critics, anthropocene-ists, animal studies folks, etc. This isn't my own interest, and I will admit to quite a lot of skepticism about broadening the idea of "literature" so much that it becomes meaningless, but it's clear that we need such a space within English departments, even for people who think plants write lit. Our departments ought to contain multitudes.

Media

I've taught media courses, and obviously have an interest in, particularly, cinema. I don't think most such studies belong in English departments, so I am inclined to like the idea of it as a separate department within a general division. While there are plenty of English teachers who teach film and media well, and as an academic field it has some of its origins there, cinema especially seems to me to need people who have significant understanding of visual and dramatic arts. (Just as "new media" [now getting old] folks probably need some understanding of basic computer science.)

Media studies is inherently a site of interdisciplinary work, and that's a good thing. Working side-by-side, people who are trained in visual arts, theatre arts, technologies, etc. can produce new ways of knowing the world.

Something that media studies can do especially well is mix practitioners and analysts. Academia really likes to separate the "practical" people from the "theory" people. This is an unfortunate separation, one that has been detrimental to English departments especially, as literary scholars and writers are too often suspicious of each other. (I'll spare you my rant about how being both a literary scholar and a creative writer is unthinkable in conventional academic English department discourse. Another time.) You'll learn a lot about understanding cinema by taking a film editing class, just as you'll learn a lot about understanding literature by taking a creative writing class. Indeed, I often think the benefit of writing workshops (and their ilk) is not in how they produce better writers, but in how they may enable better readers.

On the other hand, and to argue in some ways against myself, writing and reading teachers ought to be well versed in media, because media mediates our lives and thoughts and reading and writing. To what extent should a department of reading and writing be focused on media, I don't know. Media tends to take over. It's flashy and attracts students. But one thing I fear losing is the refuge of the English department — the one place where we can escape the flash and fizz of techno-everything, where we can sit and think about a sentence written on an old piece of paper for a while.

Education

I'm less convinced by Whitson's arguments about a division of "Composition Pedagogy and English Education". Why put Composition with English Education and not put some literary study there? Is literary study inherent in "English Education"? Why separate Composition, though? Why not call it "Teaching Reading and Writing"? Perhaps I just misunderstand the goals with this one.

It seems to me that English Education should be some sort of meta-discipline. It doesn't make much sense as a department unto itself in the scheme Whitson sets up, or most schemes, for that matter. Any sort of educational field is very difficult to set up well because it requires students not only to learn the material of their area, but to learn then how to teach that material effectively.

To me, it makes more sense to spread discussion of pedagogy throughout all departments, because one way to learn things is to try to teach them. Ideas about education, and practice at teaching, shouldn't be limited only to people who plan to become teachers, though they may need more intensive training in it.

If we want to be radical about how we restructure the discipline, integrating English Education more fully into the discipline as a whole, rather than separating it out, would be the way to go.

Writing

Whitson proposes merging creative and professional writing as one department in the division. This is an interesting idea, but I'm not convinced. Again, my own prejudices are at play: in my heart of hearts, I don't think undergraduates should major in writing. I think there should be writing courses, and there should be lots of writers employed by English departments, but the separation of writing and reading is disastrous at the undergraduate level, leading to too many writers who haven't read nearly enough and don't know how to read anything outside of their narrow, personal comfort zone.

In the late '90s, Tony Kushner scandalized the Association of Theatre in Higher Education's annual conference with a keynote speech in which he (modestly) proposed that all undergraduate arts majors be abolished. (It was published in the January 1998 issue of American Theatre magazine.) It's one of my favorite things Kushner has ever written. The whole thing is worth reading, but here's a taste:

And even if your students can tell you what iambic pentameter is and can tell you why anyone who ever sets foot on any stage in the known universe should know the answer to that and should be able to scan a line of pentameter in their sleep, how many think that "materialism" means that you own too many clothes, and "idealism" means that you volunteer to work in a soup kitchen? And why should we care? When I first started teaching at NYU, I also did a class at Columbia College, and none of my students, graduate or undergraduate (and almost all the graduate students were undergraduate arts majors--and for the past 10 years Columbia has had undergraduate arts majors), none of them, at NYU or Columbia, knew what I might mean by the idealism/materialism split in Western thought. I was so alarmed that I called a philosophy teacher friend of mine to ask her if something had happened while I was off in rehearsal, if the idealism/materialism split had become passe. She responded that it had been deconstructed, of course, but it's still useful, especially for any sort of political philosophy. By not having even a nodding acquaintance with the tradition I refer to, I submit that my students are incapable of really understanding anything written for the stage in the West, and for that matter in much of the rest of the world, just as they are incapable of reading Plato, Aristotle, Hegel, Marx, Kristeva, Judith Butler, and a huge amount of literature and poetry. They have, in essence, been excluded from some of the best their civilization has produced, and are terribly susceptible, I would submit, to the worst it has to offer.Call it the pedagogy of pulling a switcheroo. A good pedagogy, at least sometimes. It doesn't have to be, indeed should not be, limited to Western classics, as Kushner (inadvertently?) implies, and the program he calls for would not be so limited, because the kinds of conversations that he wants students to be able to recognize and join are ones that inevitably became (if they weren't already) transnational, global, even maybe a bit planetary.

What I would hope you might consider doing is tricking your undergraduate arts major students. Let them think they've arrived for vocational training and then pull a switcheroo. Instead of doing improv rehearsals, make them read The Death of Ivan Illych and find some reason why this was necessary in learning improv. They're gullible and adoring; they'll believe you. And then at least you'll know that when you die and go to the judgment seat you can say "But I made 20 kids read Tolstoy!" and this, I believe, will count much to your credit. And if you are anything like me, you'll need all the credits you can cadge together.

So yes, if I were emperor of universities, I'd abolish undergraduate arts majors, but keep lots of artists as undergraduate teachers. I'd also let the artists teach whatever the heck they wanted. Plenty of writers would be better off teaching innovative classes that aren't the gazillionth writing workshop of their career. Boxing writers into teaching only writing classes is a pernicious practice, one that perpetuates the idea that the creation of literature and the study of literature are separate activities.

But let's come back to Whitson's first proposal: planetarity and the making of textual meaning.

My own inclination is not to separate so much, but to seek out more unities. What unites us? That we study and practice ways of reading and ways of writing. We should encourage more reading in writing classes and more varied types of writing in reading classes. We should toss out our inherited, traditional nationalisms and look at other ways that texts flow around us and around not-us. (Writers do. What good writer was only influenced by texts from one nation?) We should seek out the limits of our knowledge, admit them, challenge them, celebrate them.

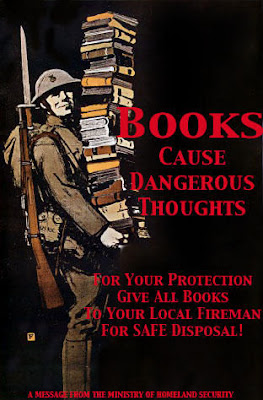

Imagination

Perhaps what we should think about is imagination. We need more imagination, and we need to educate and promote imagination. So many of the problems of our world stem from failures of imagination — from the fear of imagination. If you want to be a radical educator, be an educator who inspires students to imagine in better, fuller, deeper ways. The conservative forces of culture and society promote exactly the opposite, because the desire of the status quo is to produce unimaginative (unquestioning, obedient) subjects.

English departments, like arts departments and philosophy departments, are marvelously positioned to encourage imagination. Any student who enters an English class should leave with an expanded imagination. Any student who studies to become an English teacher should be trained in the training of imaginations. We should all be advocates for imagination, activists for its value, its necessity.

One of the best classes I've ever taught was called Writing and the Creative Process. (You can find links to a couple of the syllabi on my teaching page, though they can't really give a sense of what made the courses work well.) It was a continuously successful course in spite of me. The stakes were low, because it was an introductory course, and yet the learning we all did was sometimes life-changing. This was not my fault, but the fault of having stumbled into a pedagogy that gave itself over entirely to the practice of creativity, which is to say the practice of imagination. Because it was a pre-Creative Writing class, the focus wasn't even on becoming better writers but rather on becoming more creative (imaginative) people. That was the key to the success. Becoming a better writer is a nice goal, but becoming a more creative/imaginative person is a vital goal. Were I titling it, I'd have called that course Writing and Creative Processes, because one of the things I seek to help the students understand is that there is no one process for either writing or for thinking creatively. But no matter. Just by having to think about, talk about, and practice creativity a couple times a week, we made our lives better. I say we, because I learned as much by teaching that class as the students did; maybe more.

English departments should become departments of writing, reading, and thinking with creative processes.

I began with Spivak, so I'll come back to her, this time from her recent book Readings:

And today I am insisting that all teachers, including literary criticism teachers, are activists of the imagination. It is not a question of just producing correct descriptions, which should of course be produced, but which can always be disproved; otherwise nobody can write dissertations. There must be, at the same time, the sense of how to train the imagination, so that it can become something other than Narcissus waiting to see his own powerful image in the eyes of the other. (54)Training — encouraging, energizing — the imagination means a training in aesthetics, in techniques of structure, in ways of valuing form, in how we find and recognize and respond to the beautiful and sublime.

I'm persuaded by Steve Shaviro's arguments in No Speed Limit about aesthetics as something at least unassimilable by neoliberalism (if not in direct resistance to it): "When I find something to be beautiful, I am 'indifferent' to any uses that thing might have; I am even indifferent to whether the thing in question actually exists or not. This is why aesthetic sensation is the one realm of existence that is not reducible to political economy." (That's just a little sample. See "Accelerationist Aesthetics" for more elaboration, and the book for the full argument.)

Because the realm of the aesthetic has some ability to sit outside neoliberalism, it is in many ways the most radical realm we can submit ourselves to in the contemporary world, where neoliberalism assimilates so much else.

But training the imagination is not only an aesthetic education, it's also epistemological. Spivak again:

An epistemological performance is how you construct yourself, or anything, as an object of knowledge. I have been consistently asking you to rethink literature as an object of knowledge, as an instrument of imaginative activism. In Capital, Volume 1 (1867), for example, Marx was asking the worker to rethink him/herself, not as a victim of capitalism but as an "agent of production". That is training the imagination in epistemological performance. This is why Gramsci calls Marx's project "epistemological". It is not only epistemological, of course. Epistemological performance is something without which nothing will happen. That does not mean you stop there. Yet, without a training for this kind of shift, nothing survives. (Readings 79-80)If we're seeking, as Whitson calls us to, to create more diverse (and imaginative) departments of English, then perhaps we can do so by thinking about ways of approaching aesthetics and epistemology. We can be agents of imagination. We don't need nationalisms for that, and we don't need to strengthen divisive organizational structures that have riven many an English department.

We can — we must — imagine better.

0 Comments on Activists of the Imagination: On English as a Department, Division, Discipline as of 1/26/2016 10:58:00 AM

Add a Comment