new posts in all blogs

Viewing: Blog Posts Tagged with: language change, Most Recent at Top [Help]

Results 1 - 4 of 4

How to use this Page

You are viewing the most recent posts tagged with the words: language change in the JacketFlap blog reader. What is a tag? Think of a tag as a keyword or category label. Tags can both help you find posts on JacketFlap.com as well as provide an easy way for you to "remember" and classify posts for later recall. Try adding a tag yourself by clicking "Add a tag" below a post's header. Scroll down through the list of Recent Posts in the left column and click on a post title that sounds interesting. You can view all posts from a specific blog by clicking the Blog name in the right column, or you can click a 'More Posts from this Blog' link in any individual post.

By: Helena Palmer,

on 6/8/2015

Blog:

OUPblog

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

israel,

Linguistics,

english language,

Languages,

language change,

gaelic,

Ancient Languages,

*Featured,

Irish Language,

A History of the Irish Language,

Aidan Doyle,

Dead Languages,

History of Linguistics,

Linguistics Change,

Morphology,

Native Languages,

Books,

Language,

english,

irish,

Hebrew,

Add a tag

In the literature on language death and language renewal, two cases come up again and again: Irish and Hebrew. Mention of the former language is usually attended by a whiff of disapproval. It was abandoned relatively recently by a majority of the Irish people in favour of English, and hence is quoted as an example of a people rejecting their heritage. Hebrew, on the other hand, is presented as a model of linguistic good behaviour: not only was it not rejected by its own people, it was even revived after being dead for more than two thousand years, and is now thriving.

The post Changing languages appeared first on OUPblog.

By: Alice,

on 3/26/2014

Blog:

OUPblog

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

Books,

Language,

Oxford Etymologist,

word origins,

mood,

etymology,

anatoly liberman,

clichés,

language change,

*Featured,

Dictionaries & Lexicography,

Beguines,

Tongue-tied,

words—beggar,

Add a tag

By Anatoly Liberman

Beguines.

The origin of Beguine is bound to remain unknown, if “unknown” means that no answer exists that makes further discussion useless. No doubt, the color gray could give rise to the name. If it were not so, this etymology would not have been offered and defended by many scholars. But, as a rule, such names develop from terms of abuse (see also Stephen Goranson’ comment). I would also like to refer to pattern congruity, though in etymology it is a dangerous tool. The three words—beggar, bugger, and bigot, as well as bicker—sound alike and refer (at least the nouns do) to the same semantic sphere. To be sure, one can string together deceptively similar words that do not belong together and get wrong results. For example, the name of the protagonist in one of the most famous Icelandic sagas is Grettir. Several episodes in the saga (and even the wording) have unmistakable analogs in the Old English poem Beowulf. For this reason, Grettir and Grendel have sometimes been compared. Yet the comparison is not feasible. So to repeat, the question remains open; as usual, we are dealing with probabilities. I only hope that the picture I have drawn is not fanciful. As for the medieval Bulgarians, I think they are called Orthodox in the loosest sense of the word, that is, “not belonging to the Roman Church.” The word Beguine is Old French, and the chance of a German feminine suffix having been appended to it is vanishingly low.

Our cliché-ridden English.

Last month I touched on the buzzwords many people detest. Here (and in the next paragraph) are some more responses that I received and examples I found myself. For the reason unknown to me, I was invited to attend a demonstration of cutting edge hearing instruments. Do I need such devices in any part of my body? But unless you are, like, cutting-edge, innovative, competitive, interdisciplinary, and diverse, how can you assume the position of leadership in your branch and who will need you, you know? I have no idea, but, to quote an unrelated letter to the editor, “let’s you and I frame the discussion.”

Tongue-tied eloquence.

Nature, they say, does not tolerate void. The language of the young is full of empty holes, and it is amazing or, conversely, depressing or pathetic (chose your favorite buzzword) to observe how desperately kids try to fill them. In the capacity as a committee member I have recently looked through several hundred evaluations students at my university, from freshmen to seniors, write at the end of the courses they take (different departments, various majors, most diverse subjects). My colleagues have been praised in many ways, and it is the subtle (another buzzword) choice of epithets that impressed me most. Everybody around turned out to be awesome, just awesome. Those students who were truly overwhelmed and whose vocabulary was more nuanced wrote awesome! and awesome!! Even awesome!!! turned up once. A single fly in this awe-inspiring ointment was the writers’ predilection for calling their instructors “proffesors,” though perhaps, when one is in love, the overall number of letters in a word matters more than their distribution. The next most frequent words in the evaluations were passionate and fun. Students really enjoyed the passion for the subjects we profess and really found some of us to be helpful, especially those who are fun professors ~ proffesors, that is, the numerous “fabulous” teachers “who made it fun” or “super fun,” for, if you provide fun throughout the semester, along with occasional food and constant feedback, the students will really and “definately” miss your course “alot.” Not to be forgotten: If the assignments are clearly “layed out,” you may be called a fantastic dude or the coolest guy ever.

Foreigners complain that the vocabulary of English is almost impossible to master. They don’t realize how much can be said with very few words and that young native speakers of English find the best literature in their language so hard that they can no longer read it. Publishers cater to them and bring out books containing only the vocabulary they are able to understand, so that, to quote a perennial classic, there begins a regular competition for stupidity, with everyone trying to look even more stupid than they really are.

Gleanings in winter

Are toys “us” or “them”?

This question occurred to me when I read the following ad sent by Walter Turner:

“Another very good deed done by *** Service [no comma] which confirms their commitment to help all of us to do their family’s histories and honor them for their rich contributions to our lives.”

Of course we should do all we can to make their (= our) lives meaningful! When in trouble, always say they and their. The following excerpt will confirm the validity of this safety rule (from the Associated Press):

“Some [students] said the police response was excessive, one person said their nose was broken by a beer bottle that someone threw and another said they were ‘teargassed’.”

A good title for a thriller in the spirit of Gogol: A Person and Their Nose. Their (the person’s, the Nose’s, and collectively) problems are many.

The mood of the stories are gloomy.

Under this title, borrowed from a student paper, I occasionally quote examples of the ineradicable rule of American English that says: “Make the verb agree with the noun next to it.” In a story of the missing plane, the Associated Press informs its readers that “[a] string of previous clues have led nowhere.” Let no one tell me that string is a collective noun. Not in this case!

Language change.

I have noted in the past that the use of the agreement as in the mood of the stories are gloomy is so pervasive that one may state the rise of a new norm in American English (I don’t know how “new” it is). This is the way of language change. For example, at a certain moment, the people who have no trouble distinguishing between he and him feel at a loss when it comes to who and whom and begin to say the doctor whom we believe saved the patient. Editors and teachers fight the trend but soon they too forget what is right and what is wrong, and the more advanced (“popular”) usage takes over.

Here is an example of illogical syntax, which, if I am not mistaken, has won the day. “As a pediatrician, your editorial resonated with me,” “As an undergraduate, Prof. X showed me her handout,” and “As a valued ***customer, we have important news for you about….” I can stomach the first sentence (“I am a pediatrician, and the article has resonated with me”), but Nos. 2 and 3 strike me as nonsense: Professor X did not show the writer her handout when she, the professor, was an undergraduate. Nor is the company a valued customer. But as, among other things, means “when,” so that instead of saying “When I was an undergraduate, Professor X… showed me…,” people cut corners and say “As an undergraduate, Processor X….” Fortunately or unfortunately, the world goes its way without caring about teachers’ opinions. Change is natural (otherwise we would still be speaking Proto-Indo-European, which would be a catastrophe for historical linguists), but some sentences are so awkward that hardly anyone will like them: “I am an unwavering advocate of greater student participation in and control of student fees….” Well-meant but ugly.

My winter gleanings are over. I congratulate our readers on the coming of spring. Please send more questions and comments. In spring everybody and everything wakes up.

Anatoly Liberman is the author of Word Origins And How We Know Them as well as An Analytic Dictionary of English Etymology: An Introduction. His column on word origins, The Oxford Etymologist, appears on the OUPblog each Wednesday. Send your etymology question to him care of [email protected]; he’ll do his best to avoid responding with “origin unknown.” Subscribe to Anatoly Liberman’s weekly etymology articles via email or RSS.

Anatoly Liberman is the author of Word Origins And How We Know Them as well as An Analytic Dictionary of English Etymology: An Introduction. His column on word origins, The Oxford Etymologist, appears on the OUPblog each Wednesday. Send your etymology question to him care of [email protected]; he’ll do his best to avoid responding with “origin unknown.” Subscribe to Anatoly Liberman’s weekly etymology articles via email or RSS.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only language articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

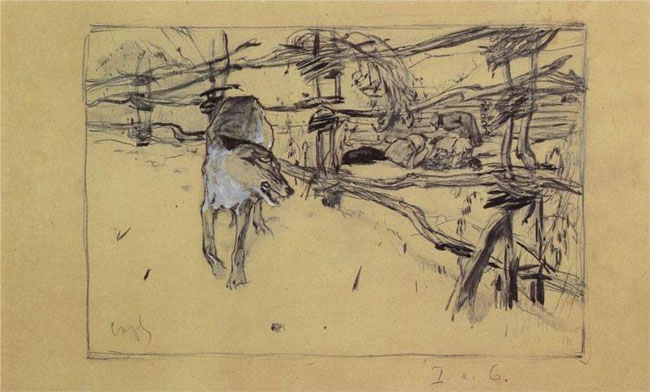

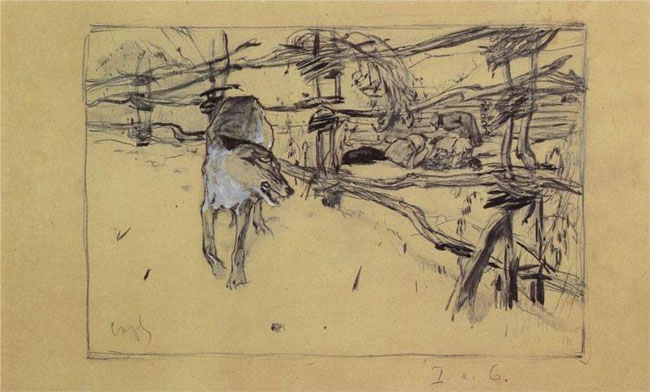

Image credit: The Wolf and the Shepherds by Valentin Serov, 1898. Public domain via Wikipaintings.

The post Monthly etymology gleanings for March 2014 appeared first on OUPblog.

By: Marc,

on 3/4/2009

Blog:

OUPblog

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

Reference,

change,

language,

A-Featured,

Oxford Etymologist,

Lexicography,

Dictionaries,

word,

word origins,

Italian,

etymology,

origins,

language change,

ghetto,

Add a tag

By Anatoly Liberman

Linguists, historians, journalists, and well-meaning amateurs have offered various conjectures on the rise of the word ghetto, none of which has won universal approval. Even the information in our best dictionaries should be treated with caution, for not all of them contain the disclaimer that whatever is said there reflects the opinion of the editor (who has rarely studied the vast literature on the subject) rather than the ultimate truth. The only uncontroversial facts are that the first Jewish ghetto appeared in Venice in 1516 and that in the Pope’s bull of 1562 the enclosure assigned to the Jews in Rome was called ghectus. (In parentheses: the Jews were expelled from England in 1290. Shakespeare wrote The Merchant of Venice around 1594; he never saw a Jew in his life. The drama is based on a widespread folklore plot of outsmarting the devil.)

Before turning to the etymology of ghetto, I would like to answer the question given in the title of this post. We don’t know whether ghetto is a Hebrew, Latin, Italian, or Yiddish word (in order not to complicate matters, I’ll refer to all the varieties of the Jewish language in the Diaspora as Yiddish, in contradistinction to Hebrew). In linguistic reconstruction, it is customary to move from the center of the enquiry to the periphery. Since the first ghetto was built in Venice, we should first look for the word’s origin in some Italian, preferably the Venetian, dialect. If this attempt fails, a Hebrew or Yiddish etymology should be tried. If we again draw blank, we will be bound to explore the vocabulary of some other language that could have influenced the coining of ghetto. Although this is a natural approach to reconstruction, it need not be confused with the natural order of things in language or anywhere in life. If I go from point A to point B, a straight line will be the shortest distance between them. But on my way I may meet a friend and go an extra mile with him, get cold and drop into a bar for a drink, or do any other unpredictable thing. Retracing my route according to the laws of geometry or logic is a dangerous enterprise. We expect an Italian origin of ghetto, but why shouldn’t the Jews have used their own word for the hateful enclosure, or why shouldn’t a foreign name for such a place have been used? After all, the word ghetto entered most European languages, including English, and it is a borrowing in all of them.

Reference books often cite the Hebrew noun get (pronounced approximately like Engl. get) “a bill or letter of divorce.” Allegedly, ghetto goes back to it and stands for “separation.” In the 16th and 17th centuries, the Jews believed that this is how the word came into being. But this connection seems to owe its existence to folk etymology, for a change from “a bill of divorce” to “a place of forced isolation” is hard to imagine. The Yiddish hypothesis makes much of ghectus understood as the Latinized form of gehektes “enclosed.” However, the spelling ghectus has little value for reconstruction. Since Latin ct became tt in Italian (compare Latin perfectus “perfect” and Italian perfetto), it was customary to give medieval Italian words a pseudo-Latin appearance. Finally, one of the oldest conjectures traces ghetto to the Latin neuter Giudaicetum “Jewish.” This etymology is indefensible from a phonetic point of view and from almost every other. The Hebrew-Yiddish search for the origin of ghetto should be abandoned.

While evaluating a dozen or so mutually conflicting theories, one should not be swayed by authority. Some of the least persuasive conjectures stem from the works of distinguished scholars. Such is the derivation of ghetto from Latin Aegyptus. The Jews were often looked upon as foreigners, but it is inconceivable that the Venetians trading with half of the world could have confused the Jews with Egyptians. Later the author of this derivation thought better of his proposal, but it found a safe haven in the most solid German dictionary and reemerged in The Oxford Dictionary of English Etymology, a fact worthy of regret. Nor are the other suggestions, all of which have been given short shrift above, the products of ignorance. The same holds for the etymology that the OED chose for want of a better one, namely, ghetto as being the second half of the Italian word borghetto “little town.” Clipping is ubiquitous in English: doc, math, lab, and their likes are universally used words. A name can lose either its first or its last syllable: Fredrick is Fred for some and Rick for others. Suburbs shrank to burbs. In Italian, ghetto (or Ghetto) “district; street” exists despite the fact that this type of word formation is much less productive, but it has been applied to numerous places unrelated to the segregation of the Jews. It is not specific enough for our purposes. Italian, like French, has two e’s: open and closed (compare the pronunciation of Engl. man and men, though the difference between the Romance vowels is smaller than in English). This difference complicates the relation between ghetto and the suffix -etto. However, the question of phonetics can be passed over here. The Venetian ghetto had a wall built around it. Christian guards closed the gates at a certain hour, so that no one could enter or leave the place. From time to time Old French guect “guard” is pressed into service: the word resembles ghectum, mentioned above, and has been cited as the etymon (source) of ghetto. The supporters of the guet etymology did not explain why a French word was used for the designation of an Italian “institution.” Those are all fruitless guesses. To remain realistic, I think we should agree that the word from which ghetto was derived denoted a certain place. Borghetto does denote a place, but referring to it is a shot in the dark.

In Italian, the first sound of ghetto is identical with g- in Engl. get, and the spelling gh- makes the pronunciation clear. In older documents our word sometimes appears with initial g- and sometimes with gh-, but gratuitous variation is so typical of medieval and early modern texts, that no conclusions can be drawn from the coexistence of ghetto and getto. In all likelihood, the 16th century Italians pronounced ghetto as we do. The Spanish and Portuguese exiles could have used the form jetto. Yet even if they did, this circumstance is of no consequence for the etymology of ghetto. The gh-g difference is the main stumbling block in the etymology that traces ghetto to the Latin verb jactare “to throw (about)”: Latin j- would not have become g-. Jactare has been conjured up because the island where the Jews were made to live at one time supposedly had getti glossed as “foundries,” and ghetto, according to an often-repeated hypothesis, received its name from getto “foundry.” Despite many attempts this hypothesis has been unable to overcome the g- ~ gh- hurdle. Getto was certainly derived from gettare “to cast (metal),” an Italian continuation of jactare, but getto is not ghetto. One also wonders whether any area would have been called “foundry” rather than “foundries.” To make matters worse, there is no certainty that getto ever meant “foundry” in the Venetian dialect. A variant of the getto-ghetto etymology connects ghetto with Old Italian ghetta “protoxide of lead.” The reference is to the verb ghettare “to refine metal by means of ghetta.” The plot thickens without bringing us closer to the denouement.

At a certain moment, I decided that all the etymologies of ghetto are wrong and was pleased to find an ally in Harri Meier, a Romance scholar, who published an article on this question in 1972. He attempted to derive ghetto from Latin vitta “ribbon,” and I liked his suggestion no more than I did those of his predecessors, but I think he was right to abandon foundries, Egyptians, borghetto, and alloys and to look for the etymon in some word meaning “street.” All over Europe, one finds a nook called Jüdische Gass(e) or its translation into the local language, that is, “Jewish Street.” Gasse is a southern German form related to Icelandic and Swedish gata (Norwegian gate, Danish gade) “street”; for the regular ss ~ t alternation compare German Wasser and Engl. water. Gata is an obscure word. Its unquestionable Gothic cognate is gatwo, but the origin of w in it has not been explained (Gothic was recorded in the 4th century). By contrast, the similar-looking Engl. gate (originally, “opening”) should probably be separated from gatwo/gata. The speakers of Old Germanic did not have towns and, consequently, did not have streets. When they needed an equivalent of “street” in Greek or Latin, they resorted to borrowing or chose a native word meaning “area” (public space) or “market.”

Surprisingly, Latin jactare will now return to our narrative. Via French, English has jetty, a derivative of this verb. Enigmatic things happened in its history. All of a sudden it seems to have developed the variant jutty. No one has even tried to explain this change that lacks analogues. The verb jet is of the same origin. It too acquired the variant jut. Jutty is restricted to dialects, but jut out is a respectable form of Standard English. The meaning of jetty also poses problems. We are familiar with jetty “pier,” but in central and northern England it means “a passage between two houses” (per The English Dialect Dictionary by Joseph Wright). In 1882 a certain A. H. G. wrote in Notes and Queries: “In rambling about Warwickshire I found the name jetty locally applied to narrow thoroughfares consisting of ancient houses, just such quarters as Houndsditch [a street in the City of London], and which might be plausibly assigned to Jews in the Middle Ages. The edifices are quite old enough for this ascription, and it may be in the power of some readers of “N. & Q.” to say if jetty is a probable corruption of ghetto, or if it is correctly spelled and used as jetty in this sense.” 126 years after A. H. G.’s query appeared I want to respond to it. I suspect that in some parts of the Romance speaking world a slangy borrowing from Germanic existed, a word traceable to gata and meaning “street,” perhaps even “narrow street,” and that it had some currency in several forms, with initial g-, as in get, and with initial j-, as in jet, with the vowel a and with the vowel e, a common situation in slang. Ghetto will then emerge as an Italian variant of that word. I suspect that from the beginning it had a derogatory meaning (“poor, miserable quarters”), the right place for the exiled Venetian Jews. Folk etymology influenced the word more than once: some people remembered that in old days cannons had been made on the Jewish island, whereas the Jews associated ghetto with separation. If I am right, the regional English sense of jetty is the most ancient; “pier” came later. In history, jutty possibly predated jetty. “It may be in the power of some readers” of this blog to develop my idea or to refute it. Whatever the result, I will be overjoyed if we succeed in making even one step toward demystifying the intractable word ghetto.

Anatoly Liberman is the author of

Word Origins…And How We Know Them as well as

An Analytic Dictionary of English Etymology: An Introduction. His column on word origins,

The Oxford Etymologist, appears here, each Wednesday. Send your etymology question to

[email protected]; he’ll do his best to avoid responding with “origin unknown.”

By: Marc,

on 2/4/2009

Blog:

OUPblog

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

names,

family,

Internet,

Reference,

change,

language,

words,

A-Featured,

Oxford Etymologist,

Lexicography,

Dictionaries,

word,

word origins,

Anatoly,

Liberman,

origins,

anatoly liberman,

texting,

buzzwords,

Americanisms,

disappearing words,

etmology,

family names,

Internet language,

language change,

separate words,

disappearing,

separate,

Add a tag

By Anatoly Liberman

The Internet and language change. The question I received can be summarized in two points. 1) Will texting and the now prevalent habit of abbreviating whole phrases (the most-often cited example is LOL “laugh out loud”) affect language development in a serious way? 2) Will the unprecedented exposure to multiple dialects and cultures that the Internet provides result in some sort of universal language? Linguistic futurology is a thankless enterprise, but my inclination is to answer no to both questions. Every message is functional. Texting, like slang and all kinds of jargon, knows its place and will hardly escape from its cell-phone cage. Some abbreviations may become words, and a statement like she lol’ed when I asked her whether she would go out with me is not unimaginable. Countless acronyms like Texaco, BS, UNO, and snafu clutter our speech; if necessary, English will survive a few more. It is the collapse of reading habits and the general degradation of culture that threaten to reduce our vocabulary to lol’able basics. As to the second part of the question, I would like to point out that the Internet is only one component of globalization. It ignores borders, but new Compuranto, destined to replace our native languages, is not yet in the offing.

Disappearing words. The question runs as follows: “For years I’ve wondered if spell-check is responsible for the disappearance of the word pled (as in he pled guilty vs. the current he pleaded guilty) and similar words that were in common usage until about twenty or so years ago. Other words that seem to have disappeared are knelt, sunk, etc.” I wonder what our readers will say. As far as I can judge, all those words are still around. In student newspapers, which reflect the poorly edited and unbuttoned-up usage of the young, I see almost only pled guilty. If anything, it is pleaded that gave way to pled in the legal phrase, probably under the influence of bled and fled. (I am not sure how many people have gone over to we pled with her but in vain). In American English, sunk seems to be the most common past tense of sink, and once, when I used sank in this blog, I was taken to task and then forgiven, when it turned out that the OED “allows” the principal parts sink—sank—sunk, like shrink—shrank—shrunk. Knelt seems to be the preferred form in British English. In any case, it is felt to be more elevated, though the OED gives both forms (knelt and kneeled) without comment. In a few other cases, American English has also chosen regular weak preterits: thus, burned, learned, spelled rather than burnt, learnt, spelt. Whatever the cause of the variation, it is clearly not the spell-check.

A family name. What is the origin of the family name Witthaus? Both witt- and haus are common elements of German family names. Strangely, Witthaus did not turn up in the most detailed dictionaries of German family names or of American last names of German descent. However, I will venture an etymology. Haus is clear (”house”). Witt- can have several sources, but, most likely, in this name it means “white” (if so, the form is northern German, Dutch, or Frisian). The European ancestors of the Witthaus family must have lived in or near a house painted white.

The origin of separate words. Handicapped. I am copying the information from The Oxford Dictionary of English Etymology, which offers a curtailed version of what can be found in the OED. The word appeared in English texts in the middle of the 17th century and meant a lottery in which one person challenged an article belonging to another, for which he offered something in exchange, an umpire being chosen to decree the respective values. In the 18th century, the phrases handicap match and handicap race surfaced. They designated a match between two horses, in which the umpire decided the extra weight to be carried by the superior horse. Hence applied to the extra weight itself, and so to any disability in a contest. Presumably, from the phrase hand i’ (in) cap, the two parties and the umpire in the original game all depositing forfeit money in a cap or hat. Shampoo. From a Hindi verb meaning “press!” (The original reference was to massage). Meltdown. Amusingly, the earliest recorded form in the OED refers to ice-cream (1937). The word acquired its ominous meaning in connection with accidents in nuclear reactors and spread to other areas; hence the meltdown of the stock market. As our correspondent notes, it has become a buzzword (and therefore should be avoided, except when reactors are meant). Hoi polloi. From Greek. It means “all people, masses.” Sun dog. Judging by the earliest citations in the OED, in the thirties of the 17th century the word was already widely known. However, its origin is said to be “obscure.” I can offer a mildly intelligent guess. Considering the superstitions attending celestial phenomena, two false suns sometimes visible on both sides of the real one could have been thought of as dogs pursuing it. The idea of two wolves following the sun and the moon, both of which try to escape their enemies and constantly move on, occurred to the medieval Scandinavians. Even the names of the wolves, Skoll (Anglicized spelling) and Hati, have come down to us. When the world comes to an end (a situation described in great detail in Scandinavian myths), the wolves catch up with and swallow their prey. As regards sundog, the missing link would be a theological or astronomical treatise that introduced and justified the use of the word. In their absence all guesses are hot air. If it is any consolation, I can say that the origin of dog days and hot dog is not obscure. The etymology of hot dog required years of painstaking research.

A few Americanisms. Conniption. Everybody seems to be in agreement that it is a “fanciful formation.” However, this phrase simply means “an individual coinage.” The question is who coined conniption and under what circumstances. I wonder whether a search for some short-lived popular song or cartoon will yield any results. Such words often come from popular culture. At the moment, we can only say that despite its classical look, conniption, which does not trace to Latin or any Romance language, must have been modeled on such nouns as conscription, constriction, conviction, and so forth. Whether a conniption fit, that is, a fit of rage or hysteria, is “related” to nip is anybody’s guess. Jaywalk. This is an equally opaque word. The verb jaywalk is a back formation on the noun jaywalker, because no other model of derivation produces English compounds made up of a noun followed by a verb. In similar fashion, kidnap is not a sum of kid and nap, but a back formation on kidnapper, another Americanism (from kid and napper “thief”), a cant word, stressed originally, like the verb, on the second element; the reference is to the people, not necessarily children, decoyed and snatched from their homes to work as servants or slaves in the colonies; such servants were often called kids: compare boy in colonial English, busboy, and cowboy, as well as the title of Robert L. Stevenson’s novel Kidnapped). It is also clear that the reference in jaywalker cannot be to the bird. Crows do not fly in a straight line, “kiddies” do not cut corners (kiddy-corner ~ cater-corner), and jays do not walk. Jay is one of the many words for a country bumpkin, along with hick, hillbilly, hayseed, redneck, and others. It has been suggested that people from rural areas (jays) came to town and, ignorant of street lights, crossed busy streets in an erratic way. Those were allegedly jaywalkers. The foundation of this etymology is shaky, since jay has never been a widespread word for a rustic. Other suggestions are even worse, and the literature on the word is all but nonexistent. Jukebox. Also a crux. Several meanings of juke have been attested, one of them being “roadside inn; brothel,” allegedly an Afro-Caribbean word. Juke refers to things disorderly and noisy, and jukeboxes were installed in saloons and other cheap places. Since jukebox originated in Black English, its African etymology is not improbable. But I would like to point out that the sound j often has an expressive function in English, whether it occurs word finally (budge, fudge, grudge, nudge) or word initially (job, jog, jig, jazz). It is perhaps a coincidence, but note that both jaywalker and juke begin with this sound. Haywire. From the use of hay-baling wire in makeshift repairs; hence “erratic, out of control.”

Hunyak. A derogatory term for a person of non-western, usually central or eastern, European background; a recent immigrant, especially an unskilled or uneducated laborer with such a background. The Dictionary of American Regional English (DARE), which has citations for these words going back to 1911, makes a plausible suggestion that hunyak (sometimes capitalized and alternating with honijoker, honyak, etc.) is perhaps a blend of Hun or Hunk “Hungarian” and Polack. There may be no need to posit a blend, for -ack is a common suffix in Slavic; it could have been added to hun-. DARE gives multiple citations of Hunk ~ hunk ~ hunks (with reinforcing -s) ~ Hungy, and so forth. Stupnagel. “Moron.” I risked a conjecture that proved to be correct. First, I rejected any connection with Hitler’s general Fr. von Stupnagel, who was not a fool (the opposite is true) and not a familiar figure in the United States. As with conniption, I suggested that the word had emerged in popular culture (a sketch, a show, or a series of cartoons) and reconstructed a character whose name was made up of stup- (from stupid) and -nagle, from finagle. Mr. Nathan E. J. Carlson, an assistant at DARE, has kindly sent me the information provided by Dr. Leonard Zwilling, that in 1931 a radio program in Buffalo, NY featured two idiots: Stoopnagle (so spelled) and Buddy. In 1933 a film was released with those characters, the first of them becoming Colonel Lemuel Q. Stoopnagle. There must have been a good reason for the change, because Lemuel is the first name of Swift’s Gulliver. I do not know what made the author introduce Stoopnagle, but my etymology (a blend of stupid and finagle) looks good. The author could also have been inspired by the German word Nagel “nail” (compare stud “nail,” with its obscene meaning, and the hero of Farrell’s novel Studs Lonigan) or perhaps wanted one of the characters to be a German, to invite a few cheap laughs. But the word stupnagle almost certainly goes back to that radio program. Judging by what one finds in the Internet, the word, but not its origin, is well-known.

A few comments on comments. Buzzwords. A fellow professor agrees with my negative attitude toward academic clichés like cutting edge and interdisciplinary, for which I am grateful. Those words shape our thought and pretend to disguise our shallowness. No grant can be received without brandishing a cutting edge, as though it were a bare bodkin, and proving one’s interdisciplinary ability to sit between two stools. Every elected official is “proud and humbled,” administrators (a vociferous chorus) rail against “an overblown sense of entitlement” by constantly promoting it, eagle-eyed journalists see the simplest things only through a “lens,” and no ad in the sphere of education will dare avoid the adjective diverse. What a dull new world! When asked about verbs like to Blagojevich, I said that verbs derived from last names seem to be rare. Several correspondents sent me what they believed to be such verbs; however, with one exception, they remembered words having suffixes (like macadamize). The exception is to Bork. Bork, a monosyllable, lends itself naturally to becoming a verb. I was glad to read that my post on Swedish kul, published in the middle of an inclement winter, warmed the cockles of a Swedish teacher’s heart (I pointed out that kul is not a borrowing of English cool), and it was interesting to read another late 19th century example of the superlative degree coolest (cool “impudent”). The correspondent who thinks that the phrase that’s all she wrote has nothing to do with Hazlitt’s time (because the contexts are different) may be right, but the old citation shows that the model for such phrases existed long before World War II.

Note. I received a question about the origin of akimbo. This word needs more than a few lines of discussion. See my post on it next Wednesday.

Anatoly Liberman is the author of

Word Origins…And How We Know Them as well as

An Analytic Dictionary of English Etymology: An Introduction. His column on word origins,

The Oxford Etymologist, appears here, each Wednesday. Send your etymology question to

[email protected]; he’ll do his best to avoid responding with “origin unknown.”

Anatoly Liberman is the author of

Anatoly Liberman is the author of

“Crows do not fly in straight lines . . .” Are you saying that the expression “As the crow flies” doesn’t allude to the black bird? What is your etymology for this expression?

Hunyak. Reading this paragraph reminded me of a word that people of my parents’ generation used in rural Minnesota: hunyucker. I don’t remember it having a racial connection, but it was mildly derogatory. I wonder if the words are related. A Google search for hunyucker only returns references to a band of that name.

An interesting insight on how a “universal language” might develop.

As the “International Year of Languages” comes to an end on 21st February, you may be interested in the contribution, made by the World Esperanto Association, to UNESCO’s campaign for the protection of endangered languages.

The following declaration was made in favour of Esperanto, by UNESCO at its Paris HQ in December 2008. http://portal.unesco.org/culture/en/ev.php-URL_ID=38420&URL_DO=DO_PRINTPAGE&URL_SECTION=201.html

The commitment to the campaign to save endangered languages was made, by the World Esperanto Association at the United Nations’ Geneva HQ in September.

http://uk.youtube.com/watch?v=eR7vD9kChBA&feature=related or http://www.lernu.net

The verbs lynch and boycott are the only ones in common use (that I know of) based on proper names: note that they are no longer capitalized, unlike Bork and Blagojevich. My favorite proper-name-with-suffix verb is the now-forgotten fletcherize, meaning to chew food until thoroughly liquefied, prototypically 28 times.

Two verbs from proper names, which are in vigorous use in the spoken language: to hoover, and to bogart.

Interestingly, bogart seems to have shifted meaning. In the 1970s, it meant to allow something to go to waste,whereas now it’s often used to mean to gather something rapaciously — to hoover it, in fact.