new posts in all blogs

Viewing: Blog Posts Tagged with: Beguines, Most Recent at Top [Help]

Results 1 - 3 of 3

How to use this Page

You are viewing the most recent posts tagged with the words: Beguines in the JacketFlap blog reader. What is a tag? Think of a tag as a keyword or category label. Tags can both help you find posts on JacketFlap.com as well as provide an easy way for you to "remember" and classify posts for later recall. Try adding a tag yourself by clicking "Add a tag" below a post's header. Scroll down through the list of Recent Posts in the left column and click on a post title that sounds interesting. You can view all posts from a specific blog by clicking the Blog name in the right column, or you can click a 'More Posts from this Blog' link in any individual post.

By: Alice,

on 3/26/2014

Blog:

OUPblog

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

Books,

Language,

Oxford Etymologist,

word origins,

mood,

etymology,

anatoly liberman,

clichés,

language change,

*Featured,

Dictionaries & Lexicography,

Beguines,

Tongue-tied,

words—beggar,

Add a tag

By Anatoly Liberman

Beguines.

The origin of Beguine is bound to remain unknown, if “unknown” means that no answer exists that makes further discussion useless. No doubt, the color gray could give rise to the name. If it were not so, this etymology would not have been offered and defended by many scholars. But, as a rule, such names develop from terms of abuse (see also Stephen Goranson’ comment). I would also like to refer to pattern congruity, though in etymology it is a dangerous tool. The three words—beggar, bugger, and bigot, as well as bicker—sound alike and refer (at least the nouns do) to the same semantic sphere. To be sure, one can string together deceptively similar words that do not belong together and get wrong results. For example, the name of the protagonist in one of the most famous Icelandic sagas is Grettir. Several episodes in the saga (and even the wording) have unmistakable analogs in the Old English poem Beowulf. For this reason, Grettir and Grendel have sometimes been compared. Yet the comparison is not feasible. So to repeat, the question remains open; as usual, we are dealing with probabilities. I only hope that the picture I have drawn is not fanciful. As for the medieval Bulgarians, I think they are called Orthodox in the loosest sense of the word, that is, “not belonging to the Roman Church.” The word Beguine is Old French, and the chance of a German feminine suffix having been appended to it is vanishingly low.

Our cliché-ridden English.

Last month I touched on the buzzwords many people detest. Here (and in the next paragraph) are some more responses that I received and examples I found myself. For the reason unknown to me, I was invited to attend a demonstration of cutting edge hearing instruments. Do I need such devices in any part of my body? But unless you are, like, cutting-edge, innovative, competitive, interdisciplinary, and diverse, how can you assume the position of leadership in your branch and who will need you, you know? I have no idea, but, to quote an unrelated letter to the editor, “let’s you and I frame the discussion.”

Tongue-tied eloquence.

Nature, they say, does not tolerate void. The language of the young is full of empty holes, and it is amazing or, conversely, depressing or pathetic (chose your favorite buzzword) to observe how desperately kids try to fill them. In the capacity as a committee member I have recently looked through several hundred evaluations students at my university, from freshmen to seniors, write at the end of the courses they take (different departments, various majors, most diverse subjects). My colleagues have been praised in many ways, and it is the subtle (another buzzword) choice of epithets that impressed me most. Everybody around turned out to be awesome, just awesome. Those students who were truly overwhelmed and whose vocabulary was more nuanced wrote awesome! and awesome!! Even awesome!!! turned up once. A single fly in this awe-inspiring ointment was the writers’ predilection for calling their instructors “proffesors,” though perhaps, when one is in love, the overall number of letters in a word matters more than their distribution. The next most frequent words in the evaluations were passionate and fun. Students really enjoyed the passion for the subjects we profess and really found some of us to be helpful, especially those who are fun professors ~ proffesors, that is, the numerous “fabulous” teachers “who made it fun” or “super fun,” for, if you provide fun throughout the semester, along with occasional food and constant feedback, the students will really and “definately” miss your course “alot.” Not to be forgotten: If the assignments are clearly “layed out,” you may be called a fantastic dude or the coolest guy ever.

Foreigners complain that the vocabulary of English is almost impossible to master. They don’t realize how much can be said with very few words and that young native speakers of English find the best literature in their language so hard that they can no longer read it. Publishers cater to them and bring out books containing only the vocabulary they are able to understand, so that, to quote a perennial classic, there begins a regular competition for stupidity, with everyone trying to look even more stupid than they really are.

Gleanings in winter

Are toys “us” or “them”?

This question occurred to me when I read the following ad sent by Walter Turner:

“Another very good deed done by *** Service [no comma] which confirms their commitment to help all of us to do their family’s histories and honor them for their rich contributions to our lives.”

Of course we should do all we can to make their (= our) lives meaningful! When in trouble, always say they and their. The following excerpt will confirm the validity of this safety rule (from the Associated Press):

“Some [students] said the police response was excessive, one person said their nose was broken by a beer bottle that someone threw and another said they were ‘teargassed’.”

A good title for a thriller in the spirit of Gogol: A Person and Their Nose. Their (the person’s, the Nose’s, and collectively) problems are many.

The mood of the stories are gloomy.

Under this title, borrowed from a student paper, I occasionally quote examples of the ineradicable rule of American English that says: “Make the verb agree with the noun next to it.” In a story of the missing plane, the Associated Press informs its readers that “[a] string of previous clues have led nowhere.” Let no one tell me that string is a collective noun. Not in this case!

Language change.

I have noted in the past that the use of the agreement as in the mood of the stories are gloomy is so pervasive that one may state the rise of a new norm in American English (I don’t know how “new” it is). This is the way of language change. For example, at a certain moment, the people who have no trouble distinguishing between he and him feel at a loss when it comes to who and whom and begin to say the doctor whom we believe saved the patient. Editors and teachers fight the trend but soon they too forget what is right and what is wrong, and the more advanced (“popular”) usage takes over.

Here is an example of illogical syntax, which, if I am not mistaken, has won the day. “As a pediatrician, your editorial resonated with me,” “As an undergraduate, Prof. X showed me her handout,” and “As a valued ***customer, we have important news for you about….” I can stomach the first sentence (“I am a pediatrician, and the article has resonated with me”), but Nos. 2 and 3 strike me as nonsense: Professor X did not show the writer her handout when she, the professor, was an undergraduate. Nor is the company a valued customer. But as, among other things, means “when,” so that instead of saying “When I was an undergraduate, Professor X… showed me…,” people cut corners and say “As an undergraduate, Processor X….” Fortunately or unfortunately, the world goes its way without caring about teachers’ opinions. Change is natural (otherwise we would still be speaking Proto-Indo-European, which would be a catastrophe for historical linguists), but some sentences are so awkward that hardly anyone will like them: “I am an unwavering advocate of greater student participation in and control of student fees….” Well-meant but ugly.

My winter gleanings are over. I congratulate our readers on the coming of spring. Please send more questions and comments. In spring everybody and everything wakes up.

Anatoly Liberman is the author of Word Origins And How We Know Them as well as An Analytic Dictionary of English Etymology: An Introduction. His column on word origins, The Oxford Etymologist, appears on the OUPblog each Wednesday. Send your etymology question to him care of [email protected]; he’ll do his best to avoid responding with “origin unknown.” Subscribe to Anatoly Liberman’s weekly etymology articles via email or RSS.

Anatoly Liberman is the author of Word Origins And How We Know Them as well as An Analytic Dictionary of English Etymology: An Introduction. His column on word origins, The Oxford Etymologist, appears on the OUPblog each Wednesday. Send your etymology question to him care of [email protected]; he’ll do his best to avoid responding with “origin unknown.” Subscribe to Anatoly Liberman’s weekly etymology articles via email or RSS.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only language articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Image credit: The Wolf and the Shepherds by Valentin Serov, 1898. Public domain via Wikipaintings.

The post Monthly etymology gleanings for March 2014 appeared first on OUPblog.

By: Alice,

on 3/19/2014

Blog:

OUPblog

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

Language,

goat,

Oxford Etymologist,

word origins,

etymology,

anatoly liberman,

buggers,

Editor's Picks,

*Featured,

bigots,

Dictionaries & Lexicography,

Beguines,

Beghards,

Albigensians,

Beggars,

Johannes Laurentius Mosheim,

Books,

Add a tag

By Anatoly Liberman

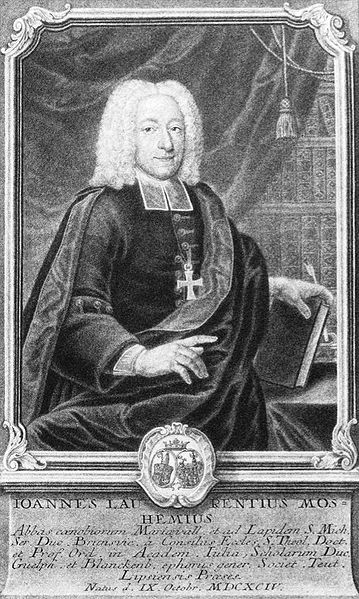

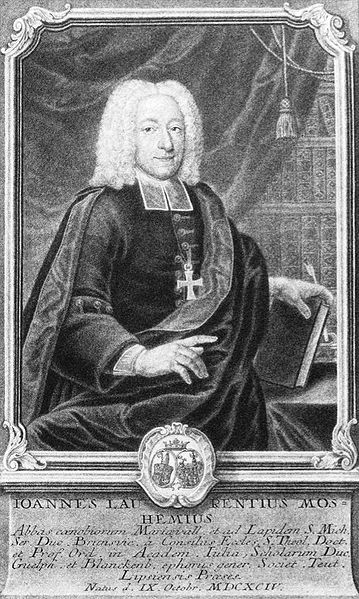

Apart from realizing that each of the three words in question (beggar, bugger, and bigot) needs an individual etymology, we should keep in mind that all of them arose as terms of abuse and sound somewhat alike. The Beguines, Beghards, and Albigensians have already been dealt with. Before going on, perhaps I should say that Johannes Laurentius Mosheim’s book De Beghardis et Beguinabus Commentarius, published by Weidmann in Leipzig, 1790, is still a most useful work to consult. The first chapter (a hundred pages) is devoted to the names Beguina, Beguinus, Begutta, and Beghardus. If I am not mistaken, this commentary, unlike his Ecclesiastic History…, has not been translated into any major European language and is available only in the original Latin.

Mosheim listed the following hypothetical sources on the derivation of Beguine and the rest: bonus-garten “good cultivator;” St. Begga, the founder of a cloister; Lambert le Bègue (the stammerer), the founder of the order; the word beguin occurring in the old dictionaries by Cotgrave and Florio (“skullcap; a kind of coarse gray cloth poor religious men wore”); the Latin adjective benignum “benign” (neuter); the German verb beginnen “begin” (because the beguttæ were about to enter monastic life); the verbs began ~ biggan “worship”; the verb began “to beg,” either as members of the mendicant orders do or perhaps from their earnest prayer to God; and finally, bi Gott. Some of those hypotheses have circulated much later (the bi Gott tale proved to be especially popular) and have been discussed in my posts. Others are too naïve to deserve our attention today, and still others, by modern scholars, will also be known to the readers of this miniseries and of the essay “Nobody wants to be a bigot.” Those interested in the way from “earnest praying” to mocking names may look up the origin of Lollard.

Mosheim listed the following hypothetical sources on the derivation of Beguine and the rest: bonus-garten “good cultivator;” St. Begga, the founder of a cloister; Lambert le Bègue (the stammerer), the founder of the order; the word beguin occurring in the old dictionaries by Cotgrave and Florio (“skullcap; a kind of coarse gray cloth poor religious men wore”); the Latin adjective benignum “benign” (neuter); the German verb beginnen “begin” (because the beguttæ were about to enter monastic life); the verbs began ~ biggan “worship”; the verb began “to beg,” either as members of the mendicant orders do or perhaps from their earnest prayer to God; and finally, bi Gott. Some of those hypotheses have circulated much later (the bi Gott tale proved to be especially popular) and have been discussed in my posts. Others are too naïve to deserve our attention today, and still others, by modern scholars, will also be known to the readers of this miniseries and of the essay “Nobody wants to be a bigot.” Those interested in the way from “earnest praying” to mocking names may look up the origin of Lollard.

The core of the problem is the similarity between the three words: bigot, beggar, and bugger. It can but need not be accidental. In the 2012 post, I made much of Maurice Grammont’s connection between bigot and Albigenses and wondered why such a good idea had escaped lexicographers. Since then I have run into several earlier passing references to this connection, which means that Grammont was not the first to trace bigot to the name of the religious order. Yet I have not seen this etymology in any dictionary. It won’t be too bold to suggest that bugger takes us to Bulgarian in its French guise (possibly confused with a homonymous swearword), bigot to Albigenses, and beggar to Beguine. The semantic root is the same, namely “heretic,” hence “pervert; scoundrel; scum,” with further specification to “fanatic” (bigot), “sodomite” (bugger), and “mendicant” (beggar). But, to repeat, it may not be fortuitous that all three words sound so much alike. The reason for the similarity seems to be the onomatopoeic complex b-g ~ b-k (the hyphen stands for any short vowel).

In various Romance Standard languages and especially dialects one finds words like bécqueter “to peck,” bégayer “to stammer” (a stammerer “pecks” at words, as it were, unable to pronounce them), bégauder “to vomit,” and Old French le gesier begaie “to split.” Part of the scene is dominated by the word for “goat” and nouns, verbs, and adjectives more or less clearly derived from it, including devices resembling the goat (either its frame or two horns). Such are bigue and bique “goat” (even the diminutive bigot “goat” and the adjective bigot “lame, limping” have been recorded); bigorna “bigot” and “lame”; bigorner “to squint.” More troublesome is Italian sbigottire “dismay, bewilder” (s-, as always, goes back to ex-) and French faire bigoter “irritate.” One is reminded of the English idiom to get one’s goat. Did it surface as a bilingual joke among the French or less probably Italian Americans? The few current explanations of this phrase strike me as fanciful. Related to sbigottire are bigollone “simpleton, fool; idler” (contrary to common sense, domestic animals—goats, cows, and rams—often epitomize foolishness, at least in idioms) and, to prove the opposite, bigatto “cunning.”

Still another bigot means “mattock; hoe.” In its vicinity we find biga ~ viga “beam’ (along with Italian biga “chariot”) and a whole world of long, elongated, split in two, and cylindrical objects: bigot (masculine plural) “spaghetti,” bigolini “short hair,” bigo “worm,” bigolo “penis” (of course: is there any verbal sphere without “penis,” or membrum virile, as the well-behaved linguists of the past glossed it?), numerous words denoting “moustache,” and quite possibly French bigoudi “hair curler” (the descendant of curl papers). My sources have been Leo Spitzer, Gerhard Rolfs, and Francesca M. Dovetto, who cite dozens of such words.

Only the names for “goat” seem to be fully transparent from an etymological point of view. Goats are often called big-big and bik-bik, even though for bleating mek and its likes occur more often than b-words. Some paths from “goat” are more easily recoverable than others. But if we stay with the idea that big- attaches itself to “stupid animals,” fools, and idlers, we will realize that, once a derogatory term for “heretic” was coined, it received strong reinforcement from many sound symbolic or sound imitative formations with negative characteristics. In such words vowels vary frequently, so that big-, beg-, and bug- were always at speakers’ “beck and call.” It was easy to humiliate a person by calling him a beggar or a bugger, regardless of the precise sense implied. The inspiration came from France. Very soon the offensive names found a new home in the Dutch-speaking world and from there traveled to England.

The words for “beak” and “pecking” can also be traced to the sound imitative complexes discussed above, which should not surprise us. While dealing with onomatopoeia, one cannot apply the terms “related” and “homonymous.” The complex b-g ~ b-k is almost universal, and its range is impossible to predict. In the Germanic languages, it often refers to swelling, as in Engl. big, bag, and bug. Swollen things burst, make a lot of noise, and frighten people; hence bugaboo, bogey, and the rest. As we have seen, the b-g ~ b-k group is used widely in coining “goat words” and terms of abuse. I would add bicker, the theme of still another recent post, to the b-k list. Its immediate source seems to have been the German, originally perhaps Dutch, word bickel, a gambling term. It would be risky to say definitely what exactly bickel meant, because in the Middle Ages the same word often meant the board game and the die (a classic example is the Latin gloss alea “a die”). Rather probably, bickel is another coinage of French descent, but where exactly it belongs among so many b-g ~ b-k nouns would be hard to tell.

We will now let the curtain fall over the history of religious prejudice, bigotry, persecution, and gambling. It is customary to admire the world of medieval and early modern carnivals. Carnivals certainly existed as a supplement to cruelty and an unbridled gratification of animal instincts. To some very small extent, this world has been subdued, but the evil words we have inherited do not allow us to forget how people lived many centuries ago. There are few windows to the past like etymology.

Anatoly Liberman is the author of Word Origins And How We Know Them as well as An Analytic Dictionary of English Etymology: An Introduction. His column on word origins, The Oxford Etymologist, appears on the OUPblog each Wednesday. Send your etymology question to him care of [email protected]; he’ll do his best to avoid responding with “origin unknown.” Subscribe to Anatoly Liberman’s weekly etymology articles via email or RSS.

Anatoly Liberman is the author of Word Origins And How We Know Them as well as An Analytic Dictionary of English Etymology: An Introduction. His column on word origins, The Oxford Etymologist, appears on the OUPblog each Wednesday. Send your etymology question to him care of [email protected]; he’ll do his best to avoid responding with “origin unknown.” Subscribe to Anatoly Liberman’s weekly etymology articles via email or RSS.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only language articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Image credit: Johann Lorenz von Mosheim (1694-1755), Kupferstich / copper engraving 1735. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

The post Beggars, buggers, and bigots, part 4 appeared first on OUPblog.

By: Alice,

on 3/5/2014

Blog:

OUPblog

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

Language,

Oxford Etymologist,

word origins,

etymology,

anatoly liberman,

beggar,

Books,

*Featured,

Dictionaries & Lexicography,

Beguines,

beguine,

beghards,

mierlo,

albigenses,

Add a tag

By Anatoly Liberman

The final sentence in the essay posted in January was not a statement but a question. We had looked at several hypotheses on the origin of the verb beg and found that none of them carried conviction. It also remained unclear whether beg was a back formation on beggar or whether beggar arose as a noun agent from the verb. Today we will examine the ideas connecting beggar with the religious order of the Beguines.

The order appeared in the thirteenth century and was active for at least three hundred years. Its modern descendants will not interest us here. As the form of the French word Beguine shows, we are dealing with a feminine noun, and, when Latinized, it was also feminine. The order took care of widows, unmarried women, and of the many solitary wives left at home by their crusading husbands. The male counterpart of the Beguines was called Beghards. In the detective story that is now unfolding (and a good etymology is always a thriller), the denouement will come next week. But it is not too early to reveal some facts. The word beggar has been tentatively derived from Beguine. However, there is a problem with this derivation: the Beguines were, at least initially, not a mendicant order — the women worked all day long. It is not even certain that, when beggars swarmed Europe and called themselves (or were called) Beguines, the connection between their occupation and the name was justified. Therefore, assuming that such a connection existed, it seems to have been established after the fact. We have to explore the etymology of the name Beguine, to see whether its inner form could suggest disapproval or perhaps a reference to the practice of asking for alms. The picture I am going to lay out is well-known, but the end result (beggars, buggers, and bigots) will be partly new.

The order appeared in the thirteenth century and was active for at least three hundred years. Its modern descendants will not interest us here. As the form of the French word Beguine shows, we are dealing with a feminine noun, and, when Latinized, it was also feminine. The order took care of widows, unmarried women, and of the many solitary wives left at home by their crusading husbands. The male counterpart of the Beguines was called Beghards. In the detective story that is now unfolding (and a good etymology is always a thriller), the denouement will come next week. But it is not too early to reveal some facts. The word beggar has been tentatively derived from Beguine. However, there is a problem with this derivation: the Beguines were, at least initially, not a mendicant order — the women worked all day long. It is not even certain that, when beggars swarmed Europe and called themselves (or were called) Beguines, the connection between their occupation and the name was justified. Therefore, assuming that such a connection existed, it seems to have been established after the fact. We have to explore the etymology of the name Beguine, to see whether its inner form could suggest disapproval or perhaps a reference to the practice of asking for alms. The picture I am going to lay out is well-known, but the end result (beggars, buggers, and bigots) will be partly new.

One guess traces Beguine to French beige “gray.” This idea has little to recommend it. Even if the Beguines and Beghards wore gray clothes, this color could not be distinctive enough for giving the name to the orders. Monks (and the Beguines/Beghards were not nuns and monks) and many other people preaching moderation and the virtues of early Christianity, quite naturally, did not parade flamboyant apparel. Think of the gray monks, associated with the Benedictines (and, if you are tired of etymology and need a really depressing thriller, reread Chekhov’s “The Black Monk”). To repeat, it is most unlikely that the Beguines were recognized mainly because they wore gray clothes.

The founder of the sisterhood of the Beguines was Lambert le Bègue. French still has the word bègue (être bègue “to stammer”). However, it is not known whether Lambert was a stammerer. The word might refer to an impediment of speech or be an ironic reference to an endless repetition (mumbling) of prayers. Not improbably, people invented the nickname Bègue in retrospect, to provide a link between the name and the order the man founded. Medieval nicknames are tricky, and their origin sometimes poses insurmountable difficulties. Even in the Middle Ages Beguines needed an explanation, and suggestions about its etymology did not go beyond intelligent guessing. References to the color and stuttering, stammering, mumbling resemble exercises in folk etymology.

In my exposition, I am strongly influenced by a series of articles by Jozef van Mierlo, who wrote them between the mid-twenties and the mid-forties of the twentieth century. His conclusions were supported by Jozef Vercoullie, a distinguished historical linguist and the author of the first modern etymological dictionary of Dutch. The names of Van Mierlo and Vercoullie say nothing to non-specialists and little to anyone outside the circle of Germanic etymologists, except of course in the Netherlands, because both scholars wrote only in Dutch (at any rate, I have not seen anything by them in French or German).

Van Mierlo traced the word Beguine to Albigenses. This was not an original idea, but we should return to it because today, as in the past, few people share it. I am not going into a discussion of the Albigensian heresy. Suffice it say that the sect was eventually crushed by the Albigensian Crusades (1209-1229). It should be borne in mind that all the events surrounding the origin of the word beggar happened in the thirteenth century, and we depend on the records whose dating does not shed enough light on linguistic reconstruction. For example, if a word surfaced in texts in the twelve-tens, it does not mean that it was unknown several decades earlier.

In any case, with the destruction of the Albigenses, their name became a term of abuse. The loss of the first syllable in such long words is common, and there are no serious arguments against tracing Beguine to Albigen-. We need to discover the origin and spread of Beguine, to understand why it gave rise to beggar (if it did!). Presumably, bigen-, the stump of Albigen-, circulated widely as an indiscriminate term of abuse (and the more frequent a word, the greater the chance that it will shed syllables). It assumed various forms, and the similarity between Beghard and beggar is strong. But to make the derivation convincing, we should take note of an intermediate step. The (Al)bigenses stood for the most detested heretics. The Beguines and Beghards did not, but they too stayed outside the mainstream and were therefore often singled out for the opprobrium of the population. Religious or any other type of tolerance was not among the most conspicuous virtues of the Middle Ages.

The label derived from “Bigensians” developed in several directions. It could acquire the senses “hypocrite” and “parasite.” This is probably how the Beguines and Beghards became “beggars.” Curiously, even today we sometimes use the word beggar to express contempt, as in poor little beggar. If my story has credence, the events developed so. A word for a certain heresy broadened its sphere and began to express abhorrence, unconnected with religion. That word was Albigenses, known well in France and the Netherlands, from where it spread to England. It lost its first syllable, and the stump began to serve as a vague term of abuse. Among other things, it yielded the French source of beggar, an English innovation. The connection between the religious order and beggar “mendicant” is real but indirect. Given this scenario, beg was a back formation on beggar, but here too the picture may be more complicated than it seems.

To be continued.

Anatoly Liberman is the author of Word Origins And How We Know Them as well as An Analytic Dictionary of English Etymology: An Introduction. His column on word origins, The Oxford Etymologist, appears on the OUPblog each Wednesday. Send your etymology question to him care of [email protected]; he’ll do his best to avoid responding with “origin unknown.” Subscribe to Anatoly Liberman’s weekly etymology articles via email or RSS.

Anatoly Liberman is the author of Word Origins And How We Know Them as well as An Analytic Dictionary of English Etymology: An Introduction. His column on word origins, The Oxford Etymologist, appears on the OUPblog each Wednesday. Send your etymology question to him care of [email protected]; he’ll do his best to avoid responding with “origin unknown.” Subscribe to Anatoly Liberman’s weekly etymology articles via email or RSS.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only language articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Image credit: Picture of a beguine woman, from Des dodes dantz, printed in Lübeck in 1489. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

The post Beggars, buggers, and bigots, part 2 appeared first on OUPblog.

Anatoly Liberman is the author of Word Origins And How We Know Them as well as An Analytic Dictionary of English Etymology: An Introduction. His column on word origins, The Oxford Etymologist, appears on the OUPblog each Wednesday. Send your etymology question to him care of [email protected]; he’ll do his best to avoid responding with “origin unknown.” Subscribe to Anatoly Liberman’s weekly etymology articles via email or RSS.

Mosheim listed the following hypothetical sources on the derivation of Beguine and the rest: bonus-garten “good cultivator;” St. Begga, the founder of a cloister; Lambert le Bègue (the stammerer), the founder of the order; the word beguin occurring in the old dictionaries by Cotgrave and Florio (“skullcap; a kind of coarse gray cloth poor religious men wore”); the Latin adjective benignum “benign” (neuter); the German verb beginnen “begin” (because the beguttæ were about to enter monastic life); the verbs began ~ biggan “worship”; the verb began “to beg,” either as members of the mendicant orders do or perhaps from their earnest prayer to God; and finally, bi Gott. Some of those hypotheses have circulated much later (the bi Gott tale proved to be especially popular) and

Mosheim listed the following hypothetical sources on the derivation of Beguine and the rest: bonus-garten “good cultivator;” St. Begga, the founder of a cloister; Lambert le Bègue (the stammerer), the founder of the order; the word beguin occurring in the old dictionaries by Cotgrave and Florio (“skullcap; a kind of coarse gray cloth poor religious men wore”); the Latin adjective benignum “benign” (neuter); the German verb beginnen “begin” (because the beguttæ were about to enter monastic life); the verbs began ~ biggan “worship”; the verb began “to beg,” either as members of the mendicant orders do or perhaps from their earnest prayer to God; and finally, bi Gott. Some of those hypotheses have circulated much later (the bi Gott tale proved to be especially popular) and  The order appeared in the thirteenth century and was active for at least three hundred years. Its modern descendants will not interest us here. As the form of the French word Beguine shows, we are dealing with a feminine noun, and, when Latinized, it was also feminine. The order took care of widows, unmarried women, and of the many solitary wives left at home by their crusading husbands. The male counterpart of the Beguines was called Beghards. In the detective story that is now unfolding (and a good etymology is always a thriller), the denouement will come next week. But it is not too early to reveal some facts. The word beggar has been tentatively derived from Beguine. However, there is a problem with this derivation: the Beguines were, at least initially, not a mendicant order — the women worked all day long. It is not even certain that, when beggars swarmed Europe and called themselves (or were called) Beguines, the connection between their occupation and the name was justified. Therefore, assuming that such a connection existed, it seems to have been established after the fact. We have to explore the etymology of the name Beguine, to see whether its inner form could suggest disapproval or perhaps a reference to the practice of asking for alms. The picture I am going to lay out is well-known, but the end result (beggars, buggers, and bigots) will be partly new.

The order appeared in the thirteenth century and was active for at least three hundred years. Its modern descendants will not interest us here. As the form of the French word Beguine shows, we are dealing with a feminine noun, and, when Latinized, it was also feminine. The order took care of widows, unmarried women, and of the many solitary wives left at home by their crusading husbands. The male counterpart of the Beguines was called Beghards. In the detective story that is now unfolding (and a good etymology is always a thriller), the denouement will come next week. But it is not too early to reveal some facts. The word beggar has been tentatively derived from Beguine. However, there is a problem with this derivation: the Beguines were, at least initially, not a mendicant order — the women worked all day long. It is not even certain that, when beggars swarmed Europe and called themselves (or were called) Beguines, the connection between their occupation and the name was justified. Therefore, assuming that such a connection existed, it seems to have been established after the fact. We have to explore the etymology of the name Beguine, to see whether its inner form could suggest disapproval or perhaps a reference to the practice of asking for alms. The picture I am going to lay out is well-known, but the end result (beggars, buggers, and bigots) will be partly new.