new posts in all blogs

Viewing: Blog Posts Tagged with: wwI, Most Recent at Top [Help]

Results 26 - 50 of 63

How to use this Page

You are viewing the most recent posts tagged with the words: wwI in the JacketFlap blog reader. What is a tag? Think of a tag as a keyword or category label. Tags can both help you find posts on JacketFlap.com as well as provide an easy way for you to "remember" and classify posts for later recall. Try adding a tag yourself by clicking "Add a tag" below a post's header. Scroll down through the list of Recent Posts in the left column and click on a post title that sounds interesting. You can view all posts from a specific blog by clicking the Blog name in the right column, or you can click a 'More Posts from this Blog' link in any individual post.

By: Kirsty,

on 7/27/2014

Blog:

OUPblog

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

Europe,

wwi,

first world war,

*Featured,

UKpophistory,

gordon martel,

july 1914,

the month that changed the world,

the july crisis,

WWI centenary,

Books,

History,

military history,

World,

world war I,

British,

This Day in History,

Add a tag

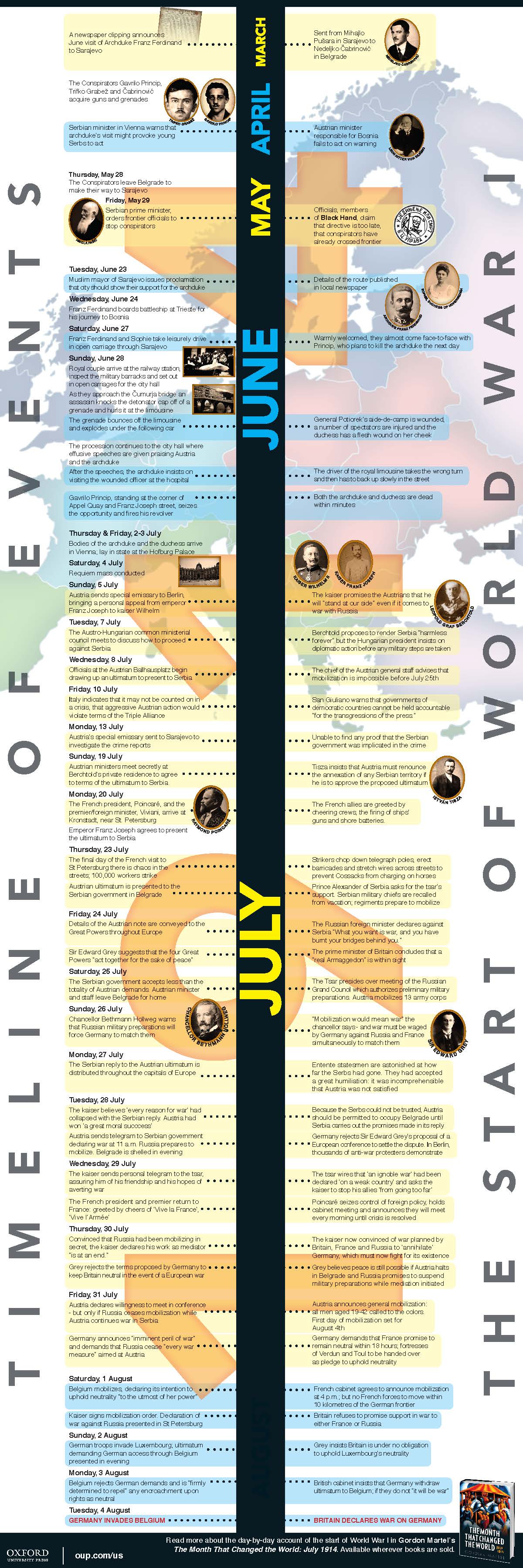

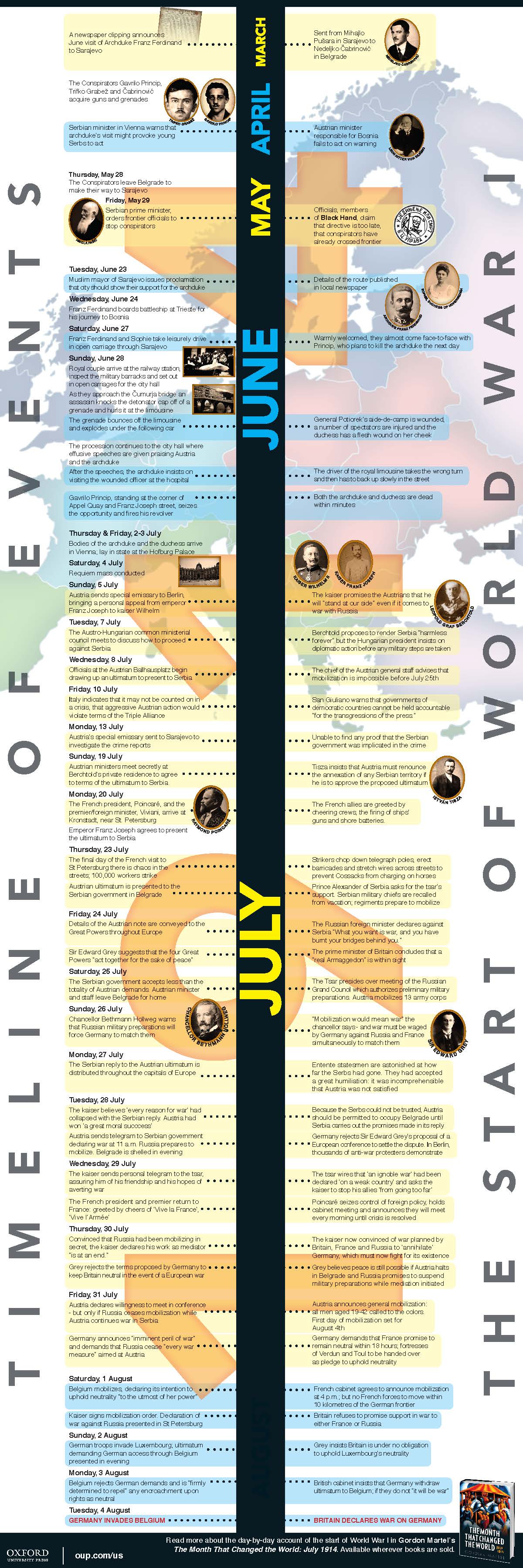

July 1914 was the month that changed the world. On 28 June 1914, Archduke Franz Ferdinand was assassinated, and just five weeks later the Great Powers of Europe were at war. But how did it all happen? Historian Gordon Martel, author of The Month That Changed The World: July 1914, is blogging regularly for us over the next few weeks, giving us a week-by-week and day-by-day account of the events that led up to the First World War.

By Gordon Martel

By the time the diplomats, politicians, and officials arrived at their offices in the morning more than 36 hours had elapsed since the Austrian deadline to Serbia had expired. And yet nothing much had happened as a consequence: the Austrian legation had packed up and left Belgrade; Austria had severed diplomatic relations with Serbia and announced a partial mobilization; but there had been no declaration of war, no shots fired in anger or in error, no wider mobilization of European armies. What action there was occurred behind the scenes, at the Foreign Office, the Ballhausplatz, the Wilhelmstrasse, the Consulta, the Quai d’Orsay, and at the Chorister’s Bridge.

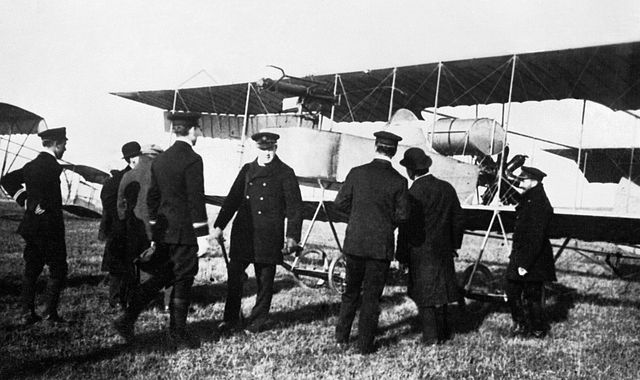

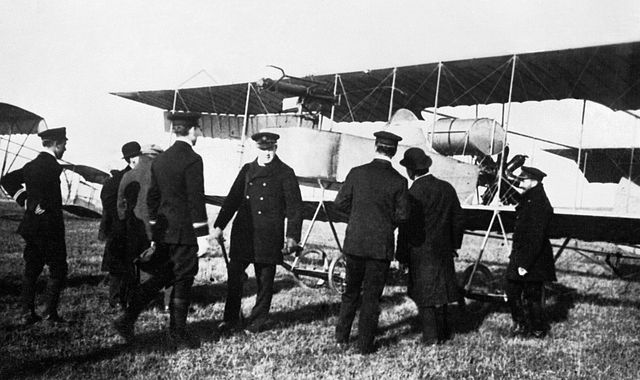

Some tentative, precautionary, steps were taken. In Russia, all lights along the coast of the Black Sea were ordered to be extinguished; the port of Sevastopol was closed to all but Russian warships; flights were banned over the military districts of St Petersburg, Vilna, Warsaw, Kiev, and Odessa. In France, over 100,000 troops stationed in Morocco and Algeria were ordered to metropolitan France; the French president and premier were asked to sail for home immediately. In Britain the cabinet agreed to keep the First and Second fleets together following manoeuvres; Winston Churchill, First Lord of the Admiralty, notified his naval commanders that war between the Triple Alliance and the Triple Entente was ‘by no means impossible’. In Germany all troops were confined to barracks. On the Danube, Hungarian authorities seized two Serbian vessels.

Winston Churchill with the Naval Wing of the Royal Flying Corps, 1914. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

Throughout the day the Serbian reply to the Austrian ultimatum was communicated throughout Europe. Austria appeared to have won great diplomatic victory. Sir Edward Grey thought the Serbs had gone farther to placate the Austrians than he had believed possible: if the Austrians refused to accept the Serbian reply as the foundation for peaceful negotiations it would be ‘absolutely clear’ that they were only seeking an excuse to crush Serbia. If so, Russia was bound to regard it as a direct challenge and the result ‘would be the most frightful war that Europe had ever seen’.

The German chancellor concluded that Serbia had complicated things by accepting almost all of the demands and that Austria was close to accomplishing everything that it wanted. The Kaiser who arrived in Kiel that morning, presided over a meeting in Potsdam at 3 p.m. where he, the chancellor, the chief of the general staff, and several more generals reviewed the situation. No dramatic decisions were taken. General Hans von Plessen, the adjutant general, recorded that they still hoped to localize the war, and that Britain seemed likely to remain neutral: ‘I have the impression that it will all blow over’.

The question of the day, then, was whether Austria would be satisfied with a resounding diplomatic victory. Russia seemed prepared to offer them one. In St Petersburg on Monday Sazonov promised to go ‘to the limit’ in accommodating them if it brought the crisis to a peaceful conclusion. He promised the German ambassador that he would they ‘build a golden bridge’ for the Austrians, that he had ‘no heart’ for the Balkan Slavs, and that he saw no problem with seven of the ten Austrian demands.

In Vienna however, Berchtold dismissed Serbia’s promises as totally worthless. Austria, he promised, would declare war the next day, or by Wednesday at the latest – in spite of the chief of the general staff’s insistence that war operations against Serbia could not begin for two weeks.

Grey was distressed to hear that Austria would treat the Serb reply as if it were a ‘decided refusal’ to comply with Austria’s wishes. The ultimatum was ‘really the greatest humiliation to which an independent State has ever been subjected’ and was surely enough to serve as foundation of a settlement.

By the end of the day on Monday, uncertainty was still widespread. Two separate proposals for reaching a settlement were now on the table: Grey’s renewed suggestion for à quatre discussions in London, and Sazonov’s new suggestion for bilateral discussions with Austria in St Petersburg. Germany had indicated that it was encouraging Austria to consider both suggestions. The German ambassador told Berlin that if Grey’s suggestion succeeded in settling the crisis with Germany’s co-operation, ‘I will guarantee that our relations with Great Britain will remain, for an incalculable time to come, of the same intimate and confidential character that has distinguished them for the last year and a half’. On the other hand, if Germany stood behind Austria and subordinated its good relations with Britain to the special interests of its ally, ‘it would never again be possible to restore those ties which have of late bound us together’.

Gordon Martel is a leading authority on war, empire, and diplomacy in the modern age. His numerous publications include studies of the origins of the first and second world wars, modern imperialism, and the nature of diplomacy. A founding editor of The International History Review, he has taught at a number of Canadian universities, and has been a visiting professor or fellow in England, Ireland and Australia. Editor-in-chief of the five-volume Encyclopedia of War, he is also joint editor of the longstanding Seminar Studies in History series. His new book is The Month That Changed The World: July 1914.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only history articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

The post The month that changed the world: Monday, 27 July 1914 appeared first on OUPblog.

By: Kirsty,

on 7/26/2014

Blog:

OUPblog

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

Books,

History,

war,

military history,

World,

British,

This Day in History,

Europe,

wwi,

World War One,

first world war,

*Featured,

kaiser,

UKpophistory,

gordon martel,

july 1914,

the month that changed the world,

martel,

the july crisis,

WWI centenary,

Add a tag

July 1914 was the month that changed the world. On 28 June 1914, Archduke Franz Ferdinand was assassinated, and just five weeks later the Great Powers of Europe were at war. But how did it all happen? Historian Gordon Martel, author of The Month That Changed The World: July 1914, is blogging regularly for us over the next few weeks, giving us a week-by-week and day-by-day account of the events that led up to the First World War.

By Gordon Martel

When day dawned on Sunday, 26 July, the sky did not fall. Shells did not rain down on Belgrade. There was no Austrian declaration of war. The morning remained peaceful, if not calm. Most Europeans attended their churches and prepared to enjoy their day of rest. Few said prayers for peace; few believed divine intervention was necessary. Europe had weathered many storms over the last decade. Only pessimists doubted that this one could be weathered as well.

In Austria-Hungary the right of assembly, the secrecy of the mail, of telegrams and telephone conversations, and the freedom of the press were all suspended. Pro-war demonstrations were not only permitted but encouraged: demonstrators filled the Ringstrasse, marched on the Ballhausplatz, gathered around statues of national heroes and sang patriotic songs. That evening the Bürgermeister of Vienna told a cheering crowd that the fate of Europe for centuries to come was about to be decided, praising them as worthy descendants of the men who had fought Napoleon. The Catholic People’s Party newspaper, Alkotmány, declared that ‘History has put the master’s cane in the Monarchy’s hands. We must teach Serbia, we must make justice, we must punish her for her crimes.’

Kaiser Wilhelm

Just how urgent was the situation? In London, Sir Edward Grey had left town on Saturday afternoon to go to his cottage for a day of fly-fishing on Sunday. The Russian ambassadors to Germany, Austria and Paris had yet to return to their posts. The British ambassadors to Germany and Paris were still on vacation. Kaiser Wilhelm was on his annual yachting cruise of the Baltic. Emperor Franz Joseph was at his hunting lodge at Bad Ischl. The French premier and president were visiting Stockholm. The Italian foreign minister was still taking his cure at Fiuggi. The chiefs of the German and Austrian general staffs remained on leave; the chief of the Serbian general staff was relaxing at an Austrian spa.

Could calm be maintained? Contradictory evidence seemed to be coming out of St Petersburg. It seemed that some military steps were being initiated – but what these were to be remained uncertain. Sazonov, the Russian foreign minister, met with both the German and Austrian ambassadors on Sunday – and both noted a significant change in his demeanour. He was now ‘much quieter and more conciliatory’. He emphatically insisted that Russia did not desire war and promised to exhaust every means to avoid it. War could be avoided if Austria’s demands stopped short of violating Serbian sovereignty. The German ambassador suggested that Russia and Austria discuss directly a softening of the demands. Sazonov, who agreed immediately to suggest this, was ‘now looking for a way out’. The Germans were assured that only preparatory measures had been undertaken thus far – ‘not a horse and not a reserve had been called to service’.

By late Sunday afternoon, the situation seemed precarious but not hopeless. The German chancellor worried that any preparatory measures adopted by Russia that appeared to be aimed at Germany would force the adoption of counter-measures. This would mean the mobilization of the German army – and mobilization ‘would mean war’. But he continued to hope that the crisis could be ‘localized’ and indicated that he would encourage Vienna to accept Grey’s proposed mediation and/or direct negotiations between Austria and Russia.

By Sunday evening more than 24 hours had passed since the Austrian legation had departed from Belgrade and Austria had severed diplomatic relations with Serbia. Many had assumed that war would follow immediately, but there had been no invasion of Serbia or even a declaration of war. The Austrians, in spite of their apparent firmness in refusing any alteration of the terms or any extension of the deadline, appeared not to know what step to take next, or when additional steps should be taken. When asked, the Austrian chief of staff suggested that any declaration of war ought to be postponed until 12 August. Was Europe really going to hold its breath for two more weeks?

Gordon Martel is a leading authority on war, empire, and diplomacy in the modern age. His numerous publications include studies of the origins of the first and second world wars, modern imperialism, and the nature of diplomacy. A founding editor of The International History Review, he has taught at a number of Canadian universities, and has been a visiting professor or fellow in England, Ireland and Australia. Editor-in-chief of the five-volume Encyclopedia of War, he is also joint editor of the longstanding Seminar Studies in History series. His new book is The Month That Changed The World: July 1914. Read his previous blog posts.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only history articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Image credit: Kaiser Wilhelm, public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

The post The month that changed the world: Sunday, 26 July 1914 appeared first on OUPblog.

By: Kirsty,

on 7/25/2014

Blog:

OUPblog

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

*Featured,

UKpophistory,

gordon martel,

july 1914,

the month that changed the world,

martel,

the july crisis,

WWI centenary,

ischl,

kaiservilla,

tornadoo,

kaiserville,

Books,

History,

military history,

World,

world war I,

austria,

British,

This Day in History,

Europe,

wwi,

first world war,

serbia,

Add a tag

July 1914 was the month that changed the world. On 28 June 1914, Archduke Franz Ferdinand was assassinated, and just five weeks later the Great Powers of Europe were at war. But how did it all happen? Historian Gordon Martel, author of The Month That Changed The World: July 1914, is blogging regularly for us over the next few weeks, giving us a week-by-week and day-by-day account of the events that led up to the First World War.

By Gordon Martel

Would there be war by the end of the day? It certainly seemed possible: the Serbs had only until 6 p.m. to accept the Austrian demands. Berchtold had instructed the Austrian representative in Belgrade that nothing less than full acceptance of all ten points contained in the ultimatum would be regarded as satisfactory. And no one expected the Serbs to comply with the demands in their entirety – least of all the Austrians.

When the Serbian cabinet met that morning they had received advice from Russia, France, and Britain urging them to be as accommodating as possible. No one indicated that any military assistance might be forthcoming. They began drafting a ‘most conciliatory’ reply to Austria while preparing for war: the royal family prepared to leave Belgrade; the military garrison left the city for a fortified town 60 miles south; the order for general mobilization was signed and drums were beaten outside of cafés, calling up conscripts.

Kaiservilla in Bad Ischl, Austria: the summer residence of Emperor Franz Joseph I. Kaiserville, Bad Ischl, Austria. By Blue tornadoo CC-BY-SA-3.0, via Wikimedia Commons

How would Russia respond? That morning the tsar presided over a meeting of the Russian Grand Council where it was agreed to mobilize the thirteen army corps designated to act against Austria. By afternoon ‘the period preparatory to war’ was initiated and preparations for mobilization began in the military districts of Kiev, Odessa, Moscow, and Kazan.

Simultaneously, Sazonov tried to enlist German support in persuading Austria to extend the deadline beyond 6 p.m., arguing that it was a ‘European matter’ not limited to Austria and Serbia. The Germans refused, arguing that to summon Austria to a European ‘tribunal’ would be humiliating and mean the end of Austria as a Great Power. Sazonov insisted that the Austrians were aiming to establish hegemony in the Balkans: after they devoured Serbia and Bulgaria Russia would face them ‘on the Black Sea’. He tried to persuade Sir Edward Grey that if Britain were to join Russia and France, Germany would then pressure Austria into moderation.

How would Britain respond? Sir Edward Grey gave no indication that Britain would stand shoulder-to-shoulder with the Russians in a conflict over Serbia. His only concern seemed to be to contain the crisis, to keep it a dispute between Austria and Serbia. ‘I do not consider that public opinion here would or ought to sanction our going to war over a Servian quarrel’. But if a war between Austria and Serbia were to occur ‘other issues’ might draw Britain in. In the meantime, there was still an opportunity to avert war if the four disinterested powers ‘held the hand’ of their partners while mediating the dispute. But the report he received from St Petersburg was not encouraging: the British ambassador warned that Russia and France seemed determined to make ‘a strong stand’ even if Britain declined to join them.

When the Austrian minister received the Serb reply at 5:58 on Saturday afternoon, he could see instantly that their submission was not complete. He announced that Austria was breaking off diplomatic relations with Serbia and immediately ordered the staff of the delegation to leave for the railway station. By 6:30 the Austrians were on a train bound for the border.

That evening, in the Kaiservilla at Bad Ischl, Franz Joseph signed the orders for mobilization of thirteen army corps. When the news reached Vienna the people greeted it with the ‘wildest enthusiasm’. Huge crowds began to form, gathering at the Ringstrasse and bursting into patriotic songs. The crowds marched around the city shouting ‘Down with Serbia! Down with Russia’. In front of the German embassy they sang ‘Wacht am Rhein’; police had to protect the Russian embassy against the demonstrators. Surely, it would not be long before the guns began firing.

Gordon Martel is a leading authority on war, empire, and diplomacy in the modern age. His numerous publications include studies of the origins of the first and second world wars, modern imperialism, and the nature of diplomacy. A founding editor of The International History Review, he has taught at a number of Canadian universities, and has been a visiting professor or fellow in England, Ireland and Australia. Editor-in-chief of the five-volume Encyclopedia of War, he is also joint editor of the longstanding Seminar Studies in History series. His new book is The Month That Changed The World: July 1914.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only history articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

The post The month that changed the world: Saturday, 25 July 1914 appeared first on OUPblog.

By: Kirsty,

on 7/24/2014

Blog:

OUPblog

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

Books,

History,

military history,

World,

austria,

British,

This Day in History,

Europe,

wwi,

World War One,

first world war,

hungary,

Serbia,

*Featured,

serbian,

UKpophistory,

gordon martel,

july 1914,

the month that changed the world,

martel,

july crisis,

Berchtold,

Edward Grey,

Austria-Hungary,

Austrian ultimatum,

Sazonov,

sergey,

Add a tag

July 1914 was the month that changed the world. On 28 June 1914, Archduke Franz Ferdinand was assassinated, and just five weeks later the Great Powers of Europe were at war. But how did it all happen? Historian Gordon Martel, author of The Month That Changed The World: July 1914, is blogging regularly for us over the next few weeks, giving us a week-by-week and day-by-day account of the events that led up to the First World War.

By Gordon Martel

By mid-day Friday heads of state, heads of government, foreign ministers, and ambassadors learned the terms of the Austrian ultimatum. A preamble to the demands asserted that a ‘subversive movement’ to ‘disjoin’ parts of Austria-Hungary had grown ‘under the eyes’ of the Serbian government. This had led to terrorism, murder, and attempted murder. Austria’s investigation of the assassination of the archduke revealed that Serbian military officers and government officials were implicated in the crime.

A list of ten demands followed, the most important of which were: Serbia was to suppress all forms of propaganda aimed at Austria-Hungary; the Narodna odbrana was to be dissolved, along with all other subversive societies; officers and officials who had participated in propaganda were to be dismissed; Austrian officials were to participate in suppressing the subversive movements in Serbia and in a judicial inquiry into the assassination.

When Sazonov saw the terms he concluded that Austria wanted war: ‘You are setting fire to Europe!’ If Serbia were to comply with the demands it would mean the end of its sovereignty. ‘What you want is war, and you have burnt your bridges behind you’. He advised the tsar that Serbia could not possibly comply, that Austria knew this and would not have presented the ultimatum without the promise of Germany’s support. He told the British and French ambassadors that war was imminent unless they acted together.

But would they? With the French president and premier now at sea in the Baltic, and with wireless telegraphy problematic, foreign policy was in the hands of Bienvenu-Martin, the inexperienced minister of justice. He believed that Austria was within its rights to demand the punishment of those implicated in the crime and he shared Germany’s wish to localize the dispute. Serbia could not be expected to agree to demands that impinged upon its sovereignty, but perhaps it could agree to punish those involved in the assassination and to suppress propaganda aimed at Austria-Hungary.

Sir Edward Grey was shocked by the extent of the demands. He had never before seen ‘one State address to another independent State a document of so formidable a character.’ The demand that Austria-Hungary be given the right to appoint officials who would have authority within the frontiers of Serbia could not be consistent with Serbia’s sovereignty. But the British government had no interest in the merits of the dispute between Austria and Serbia; its only concern was the peace of Europe. He proposed that the four ‘disinterested powers’ (Britain, Germany, France and Italy) act together at Vienna and St Petersburg to resolve the dispute. After Grey briefed the cabinet that afternoon, the prime minister concluded that although a ‘real Armaggedon’ was within sight, ‘there seems…no reason why we should be more than spectators’.

Nothing that the Austrians or the Germans heard in London or Paris on Friday caused them to reconsider their course. In fact, their general impression was that the Entente Powers wished to localize the dispute. Even from St Petersburg the German ambassador reported that Sazonov’s reference to Austria’s ‘devouring’ of Serbia meant that Russia would take up arms only if Austria seized Serbian territory and that his wish to ‘Europeanize’ the dispute indicated that Russia’s ‘immediate intervention’ need not be anticipated.

Berchtold made his position clear in Vienna that afternoon: ‘the very existence of Austria-Hungary as a Great Power’ was at stake; Austria-Hungary must give proof of its stature as a Great Power ‘by an outright coup de force’. When the Russian chargé d’affaires asked him how Austria would respond if the time limit were to expire without a satisfactory answer from Serbia, Berchtold replied that the Austrian minister and his staff had been instructed in such circumstances to leave Belgrade and return to Austria. Prince Kudashev, after reflecting on this, exclaimed ‘Alors c’est la guerre!’

Gordon Martel is a leading authority on war, empire, and diplomacy in the modern age. His numerous publications include studies of the origins of the first and second world wars, modern imperialism, and the nature of diplomacy. A founding editor of The International History Review, he has taught at a number of Canadian universities, and has been a visiting professor or fellow in England, Ireland and Australia. Editor-in-chief of the five-volume Encyclopedia of War, he is also joint editor of the longstanding Seminar Studies in History series. His new book is The Month That Changed The World: July 1914.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only history articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

The post The month that changed the world: Friday, 24 July 1914 appeared first on OUPblog.

By: Kirsty,

on 7/20/2014

Blog:

OUPblog

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

Books,

military history,

first world war,

Edward Grey,

Franz Joseph,

Raymond Poincaré,

René Viviani,

San Giuliano,

History,

World,

British,

This Day in History,

Europe,

wwi,

World War One,

serbia,

*Featured,

UKpophistory,

gordon martel,

july 1914,

the month that changed the world,

july crisis,

Lazar Paču,

Sergei Sazonov,

poincaré,

Add a tag

July 1914 was the month that changed the world. On 28 June 1914, Archduke Franz Ferdinand was assassinated, and just five weeks later the Great Powers of Europe were at war. But how did it all happen? Historian Gordon Martel, author of The Month That Changed The World: July 1914, is blogging regularly for us over the next few weeks, giving us a week-by-week and day-by-day account of the events that led up to the First World War.

By Gordon Martel

The French delegation, led by President Raymond Poincaré and the premier/foreign minister René Viviani, finally arrived in Russia. They boarded the imperial yacht, the Alexandria, while a Russian band played the ‘Marseillaise’ – that revolutionary ode to the destruction of royal and aristocratic privilege. The tsar and his foreign minister welcomed the visitors before they travelled to Peterhof where a spectacular banquet awaited them.

While the leaders of republican France and tsarist Russia were proclaiming their mutual admiration for one another, the Habsburg emperor was approving the terms of the ultimatum to be presented to Serbia three days later. No one was to be forewarned, not even their allies: Italy was to be told on Wednesday only that a note would be presented on Thursday; Germany was not to be given the details of the ultimatum until Friday – along with everyone else.

In London, Sir Edward Grey remained in the dark. He was optimistic; he told the German ambassador on Monday that a peaceful solution would be reached. It was obvious that Austria was going to make demands on Serbia, including guarantees for the future, but Grey believed that everything depended on the form of the demands, whether the Austrians would exercise moderation, and whether the accusations of Serb government complicity were convincing. If Austria kept its demands within ‘reasonable limits’ and if the necessary justification was provided, it ought to be possible to prevent a breach of the peace; ‘that any of them should be dragged into a war by Serbia would be detestable’.

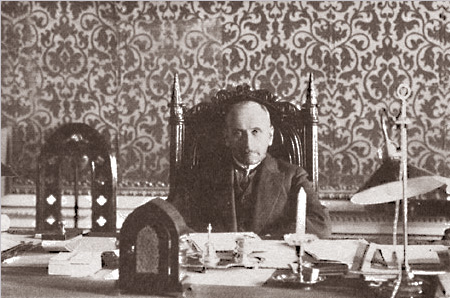

Raymond Poincaré, President of France, public domain

On Tuesday the Germans complained that the Austrians were keeping them in the dark. From Berlin, the Austrian ambassador offered Berchtold his ‘humble opinion’ that the Germans ought to be given the details of the ultimatum immediately. After all, the Kaiser ‘and all the others in high offices’ had loyally promised their support from the first; to treat Germany in the same manner as all the other powers ‘might give offence’. Berchtold agreed to give the German ambassador a copy of the ultimatum that evening; the details should arrive at the Wilhelmstrasse by Wednesday.

That same day the French visitors arrived in St Petersburg, where the mayor offered the president bread and salt – according to an old Slavic custom – and Poincaré laid a wreath on the tomb of Alexander III ‘the father’ of the Franco-Russian alliance. In the afternoon they travelled to the Winter Palace for a diplomatic levee. Along the route they were greeted by enthusiastic crowds: ‘The police had arranged it all. At every street corner a group of poor wretches cheered loudly under the eye of a policeman.’ Another spectacular banquet was held that evening, this time at the French embassy.

Perhaps the presence of the French emboldened the Russians. The foreign minister, Sergei Sazonov, warned the German ambassador that he perceived ‘powerful and dangerous influences’ might plunge Austria into war. He blamed the Austrians for the agitation in Bosnia, which arose from their misgovernment of the province. Now there were those who wanted to take advantage of the assassination to annihilate Serbia. But Russia could not look on indifferently while Serbia was humiliated, and Russia was not alone: they were now taking the situation very seriously in Paris and London.

But stern warnings in St Petersburg were not repeated elsewhere. In Vienna the French ambassador believed as late as Wednesday that Russia would not take an active part in the dispute and would try to localize it. The Russian ambassador there was so confident of a peaceful resolution that he left for his vacation that afternoon. The Russian ambassador in Berlin had already left for vacation and had yet to return; the French ambassador there returned on Thursday. The British ambassador was also absent and Grey saw no need to send him back to Berlin.

In Rome however, San Giuliano had no doubt that Austria was carefully drafting demands that could not be accepted by Serbia. He no longer believed that Franz Joseph would act as a moderating influence. The Austrian government was now determined to crush Serbia and seemed to believe that Russia would stand by and allow Serbia to ‘be violated’. Germany, he predicted, ‘would make no effort’ to restrain Austria.

By Thursday, 23 July, twenty-five days had passed since the assassination. Twenty-five days of rumours, speculations, discussions, half-truths, and hypothetical scenarios. Would the Austrian investigation into the crime prove that the instigators were directed from or supported by the government in Belgrade? Would the Serbian government assist in rooting out any individuals or organizations that may have provided assistance to the conspirators? Would Austria’s demands be limited to steps to ensure that the perpetrators would be brought to justice and such outrages be prevented from recurring in the future? Or would the assassination be utilized as a pretext for dismembering, crushing or abolishing the independence of Serbia as a state? Was Germany restraining Austria or goading it to act? Would Russia stand with Serbia in resisting Austrian demands? Would France encourage Russia to respond with restraint or push it forward? Would Italy stick with her alliance partners, stand aside, or join the other side? Could Britain promote a peaceful resolution by refusing to commit to either side in the dispute, or could it hope to counterbalance the Triple Alliance only by acting in partnership with its friends in the entente? At last, at least some of these questions were about to be answered.

At ‘the striking of the clock’ at 6 p.m. on Thursday evening the Austrian note was presented in Belgrade to the prime minister’s deputy, the chain-smoking Lazar Paču, who immediately arranged to see the Russian minister to beg for Russia’s help. Even a quick glance at the demands made in the note convinced the Serbian Crown Prince that he could not possibly accept them. The chief of the general staff and his deputy were recalled from their vacations; all divisional commanders were summoned to their posts; railway authorities were alerted that mobilization might be declared; regiments on the northern frontier were instructed to prepare assembly points for an impending mobilization. What would become the most famous diplomatic crisis in history had finally begun.

Gordon Martel is a leading authority on war, empire, and diplomacy in the modern age. His numerous publications include studies of the origins of the first and second world wars, modern imperialism, and the nature of diplomacy. A founding editor of The International History Review, he has taught at a number of Canadian universities, and has been a visiting professor or fellow in England, Ireland and Australia. Editor-in-chief of the five-volume Encyclopedia of War, he is also joint editor of the longstanding Seminar Studies in History series. His new book is The Month That Changed The World: July 1914. Read his previous blog posts.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only history articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Image credit: Raymond Poincaré, public domain via Wikimedia Commons

The post The month that changed the world: Monday, 20 July to Thursday, 23 July 1914 appeared first on OUPblog.

By: Kirsty,

on 7/13/2014

Blog:

OUPblog

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

military history,

World,

British,

This Day in History,

Europe,

wwi,

World War One,

first world war,

*Featured,

UKpophistory,

Austro-Hungarian Empire,

gordon martel,

july 1914,

the month that changed the world,

july crisis,

Berchtold,

Triple Alliance,

Lichnowsky,

Tisza,

Triple Entente,

Books,

History,

Add a tag

July 1914 was the month that changed the world. On 28 June 1914, Archduke Franz Ferdinand was assassinated, and just five weeks later the Great Powers of Europe were at war. But how did it all happen? Historian Gordon Martel, author of The Month That Changed The World: July 1914, is blogging regularly for us over the next few weeks, giving us a week-by-week and day-by-day account of the events that led up to the First World War.

By Gordon Martel

Two weeks after the assassination, by Monday, 13 July, Austria’s hopes of pinning the guilt directly on the Serbian government had evaporated. The judge sent to investigate reported that he had been unable to discover any evidence proving its complicity in the plot. Perhaps the Russian foreign minister was right to dismiss the assassination as having been perpetrated by immature young men acting on their own. Any public relations initiative undertaken by Austria to justify making harsh demands on Serbia would have to rely on its failure to live up to the promises it had made five years ago to exist on good terms with Austria-Hungary.

Few anticipated an international crisis. Entente diplomats remained convinced that Germany would restrain Austria, while the British ambassador in Vienna still regarded Berchtold as ‘peacefully inclined’ and believed that it would be difficult to persuade the emperor to sanction an ‘aggressive course of action’. Triple Alliance diplomats found it difficult to envision a robust response from the Entente powers to any Austrian initiative: the cities of western Russia were plagued by devastating strikes; the possibility of civil war in Ulster loomed as a result of the British government’s home rule bill; the French public was already absorbed by the upcoming murder trial of the wife of a cabinet minister.

Austria and Germany tried to maintain an aura of calm. The chief of the Austrian general staff left for his annual vacation on Monday; the minister of war joined him on Wednesday. The chief of the German general staff continued to take the waters at a spa, while the Kaiser was encouraged not to interrupt his Baltic cruise. But behind the scenes they were resolved to act. On Tuesday Tisza assured the German ambassador that he was now ‘firmly convinced’ of the necessity of war: Austria must seize the opportunity to demonstrate its vitality; together with Germany they would now ‘look the future calmly and firmly in the face’. Berchtold explained to Berlin that the presentation of the ultimatum would be have to be delayed: the president and the premier of France would be visiting Russia on the 20-23 of July, and it was not desirable to have them there, in direct contact with the Russian government, when the demands were made. But Berchtold wanted to assure Germany that this did not indicate any ‘hesitation or uncertainty’ in Vienna. The German chancellor was unwavering in his support: he was determined to stand by Austria even if it meant taking ‘a leap into the dark’.

German statesman and diplomat Gottlieb von Jagow

One of the few discordant voices was heard from London, where Prince Lichnowsky was becoming more assertive: he tried to warn Berlin of the consequences of supporting an aggressive Austrian initiative. British opinion had long supported the principle of nationality and their sympathies would ‘turn instantly and impulsively to the Serbs’ if the Austrians resorted to violence. This was not what Berlin wished to hear. Jagow replied that this might be the last opportunity for Austria to deal a death-blow to the ‘menace of a Greater Serbia’. If Austria failed to seize the opportunity its prestige ‘will be finished’, and its status was of vital interest to Germany. He prompted a German businessman to undertake a private mission to London to go around the back of his ambassador.

The German chancellor remained hopeful. Bethmann Hollweg believed that Britain and France could be used to restrain Russia from intervening on Serbia’s behalf. But the support of Italy was questionable. In Rome, the Italian foreign minister argued that the Serbian government could not be held responsible for the actions of men who were not even its subjects. Italy could not offer assistance if Austria attempted to suppress the Serbian national struggle by the use of violence – or at least not unless sufficient ‘compensation’ was promised in advance.

From London Lichnowsky continued to insist that a war would neither solve Austria’s Slav problem nor extinguish the Greater Serb movement. There was no hope of detaching Britain from the Entente and Germany faced no imminent danger from Russia. Germany, he complained, was risking everything for ‘mere adventure’.

These warnings fell on deaf ears: instead of reconsidering Germany’s options the chancellor lost his confidence in Lichnowsky. Instead of recognising that Italy would fail to support its allies in a war, the German government pressed Vienna to offer compensation to Italy sufficient to change its mind. By Saturday, the secretary of state was explaining that this was Austria’s last chance for ‘rehabilitation’ and that if it were to fail its standing as a Great Power would disappear forever. The alternative was Russian hegemony in the Balkans – something that Germany could not permit. The greater the determination with which Austria acted, the more likely it was that Russia would remain quiet. Better to act now: in a few years Russia would be prepared to fight, and then ‘she will crush us by the number of her soldiers.’

On Sunday morning the ministers of the Austro-Hungarian common council gathered secretively at Betchtold’s private residence, arriving in unmarked cars. This time there was no controversy. After minimal discussion the terms of the ultimatum to be presented to Serbia were agreed upon. Count Hoyos recorded that the demands were such that no nation ‘that still possessed self- respect and dignity could possibly accept them’. They agreed to present the note containing them in Belgrade between 4 and 5 p.m. on Thursday, the 25th. If Serbia failed to reply positively within 48 hours Austria would begin to mobilize its armed forces.

Gordon Martel is a leading authority on war, empire, and diplomacy in the modern age. His numerous publications include studies of the origins of the first and second world wars, modern imperialism, and the nature of diplomacy. A founding editor of The International History Review, he has taught at a number of Canadian universities, and has been a visiting professor or fellow in England, Ireland and Australia. Editor-in-chief of the five-volume Encyclopedia of War, he is also joint editor of the longstanding Seminar Studies in History series. His new book is The Month That Changed The World: July 1914.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only history articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Image credit: Gottlieb von Jagow, public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

The post The month that changed the world: Monday, 13 July to Sunday, 19 July 1914 appeared first on OUPblog.

Duffy, Chris, ed. 2014. Above the Dreamless Dead: World War I in Poetry and Comics. New York: First Second.

Duffy, Chris, ed. 2014. Above the Dreamless Dead: World War I in Poetry and Comics. New York: First Second.

(Advance Reader Copy)

Above the Dreamless Dead is an illustrated anthology of poetry by English soldier-poets, who served in WWI. They are known collectively as the "Trench Poets."

Poems by famous writers such as Wilfred Owen and Rudyard Kipling are illustrated by equally talented comic artists, including Hannah Berry and George Pratt. The comic-style renderings (most spanning many pages), offer complementary interpretations of these century-old poems. The benefit of hindsight and perspective give the artists a broader angle in which to work. The result is a very personal, haunting, and moving look at The Great War.

|

This is the "case" for Above the Dreamless Dead.

This, and many other interior photos at 00:01 First Second. |

Look for

Above the Dreamless Dead in September, 2014. Thanks to

First Second, who provided this review copy at my request.

|

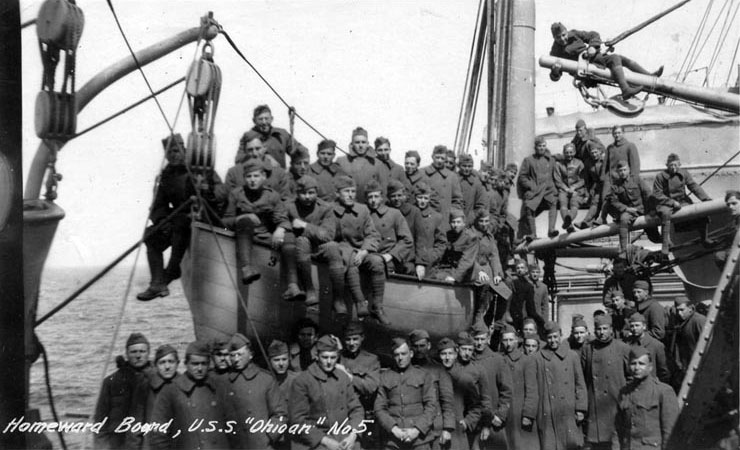

French soldiers of the 87th Regiment, 6th Division,

at Côte 304, (Hill 304), northwest of Verdun, 1916.

Public Domain image. |

Note: Although this is not an anthology for children, it should be of interest to teens and teachers. It could be particularly useful in meeting Common Core State Standards by combining art, poetry, history, and nonfiction.

By: Kirsty,

on 7/6/2014

Blog:

OUPblog

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

Books,

History,

military history,

World,

British,

This Day in History,

Europe,

wwi,

World War One,

first world war,

serbia,

*Featured,

UKpophistory,

gordon martel,

july 1914,

the month that changed the world,

july crisis,

Berchtold,

Conrad von Hötzendorff,

Gottlieb von Jagow,

Sir Edward Grey,

Theobald von Bethmann Hollweg,

Triple Alliance,

Add a tag

July 1914 was the month that changed the world. On 28 June 1914, Archduke Franz Ferdinand was assassinated, and just five weeks later the Great Powers of Europe were at war. But how did it all happen? Historian Gordon Martel, author of The Month That Changed The World: July 1914, is blogging regularly for us over the next few weeks, giving us a week-by-week and day-by-day account of the events that led up to the First World War.

By Gordon Martel

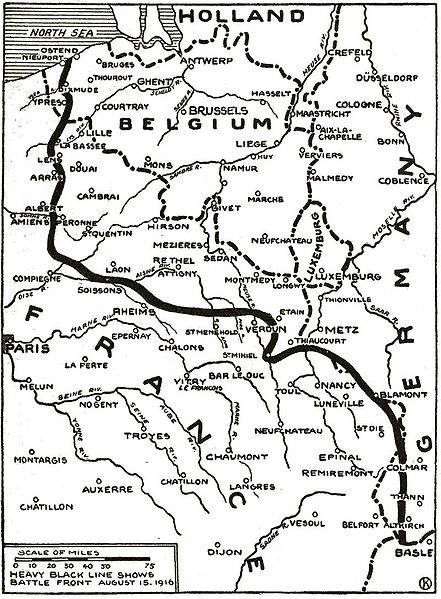

Having assured the Austrians of his support on Sunday, the kaiser on Monday departed on his yacht, the Hohenzollern, for his annual summer cruise of the Baltic. When his chancellor, Theobald von Bethmann Hollweg, met with Count Hoyos and the Austrian ambassador in Berlin that afternoon, he confirmed that Germany would stand by them ‘shoulder-to-shoulder’. He agreed that Russia was attempting to form a ‘Balkan League’ which threatened the interests of the Triple Alliance. He promised to seize the initiative: he would begin negotiations to bring Bulgaria into the alliance and he would advise Romania to stop nationalist agitation there against Austria. He would leave it to the Austrians to decide how to proceed with Serbia, but they ‘may always be certain that Germany will remain at our side as a faithful friend and ally’.

In London the German ambassador, now back from a visit home, arranged to meet with the British foreign secretary, Sir Edward Grey, on Monday afternoon. Prince Lichnowsky aimed to persuade Grey that Germany and Britain should co-operate to ‘localize’ the dispute between Austria and Serbia. Lichnowsky explained that the feeling was growing in Germany that it was better not to restrain Austria, to ‘let the trouble come now, rather than later’ and he reported that Grey understood Austria would have to adopt ‘severe measures’.

On Tuesday the Austrian government met in Vienna to determine precisely how far and how fast they were prepared to move against Serbia. The meeting went on for most of the day. The emperor did not attend; in fact, he left the city that morning to return to his hunting lodge, five hours away, where he would remain for the next three weeks. Berchtold, in the chair, told the assembled ministers that the moment had come to decide whether to render Serbia’s intrigues harmless forever. He assured them that Germany had promised its support in the event of any ‘warlike complications’.

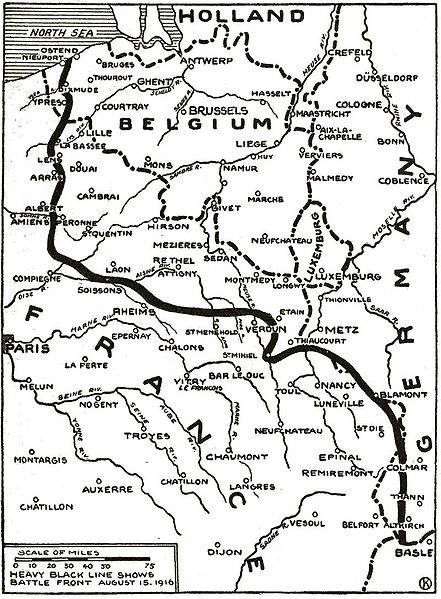

The Triple Alliance

The ministers agreed that vigorous measures were needed. Only the Hungarian minister-president expressed any concern. Tisza insisted that they prepare the diplomatic ground before taking any military action, otherwise they would be discredited in the eyes of Europe. They should begin by presenting Serbia with a list of demands: if these were accepted they would have achieved a splendid diplomatic victory; if they were rejected, he would vote for war. Berchtold and the others disagreed: only by the exertion of force could the fundamental problem of the propaganda for a Greater Serbia emanating from Belgrade be eliminated. The argument went on for hours, but Tisza had the power of a virtual veto: Austria-Hungary could not go to war without his agreement. Reluctantly, the ministers agreed to formulate a set of demands to present to Serbia. These should be so stringent however as to make refusal ‘almost certain’.

On Wednesday, 8 July, officials at the Ballhausplatz began working on the draft of an ultimatum to be presented to Serbia. They were in no hurry. The chief of the general Staff, Conrad von Hötzendorff, had determined that, with so many conscript soldiers on leave to assist in the gathering of the harvest, it would be impossible to begin mobilization before 25 July. The ultimatum could not be presented until 22-23 July.

By Thursday in Berlin they were beginning to envision a diplomatic victory for the Triple Alliance. The secretary of state, Gottlieb von Jagow, just returned from his honeymoon, told the Italian ambassador that Austria could not afford to be submissive when confronted by a Serbia ‘sustained or driven on by the provocative support of Russia’. But he did not believe that ‘a really energetic and coherent action’ on their part would lead to a conflict. From London, Prince Lichnowsky reported that Sir Edward Grey had reassured him that he had made no secret agreements with France and Russia that entailed any obligations in the event of a European war. Rather, Britain wished to preserve the ‘absolutely free hand’ that would allow it to act according to its own judgement. Grey appeared confident, cheerful and ‘not pessimistic’ about the situation in the Balkans.

Meeting with the German ambassador in Vienna on Friday, Berchtold sketched some preliminary ideas of what the ultimatum to Serbia might consist of. Perhaps they might demand that an agency of the Austro-Hungarian government be established at Belgrade to monitor the machinations of the ‘Greater Serbia’ movement; perhaps they might insist that some nationalist organizations be dissolved; perhaps they could stipulate that certain army officers be dismissed. He wanted to be sure that the demands went so far that Serbia could not possibly accept them. What did they think in Berlin?

Berlin chose not to think anything. The ambassador was instructed to inform Berchtold that Germany could take no part in formulating the demands. Instead, he was advised to collect evidence that would show the Greater Serbia agitation in Belgrade threatened Austria’s existence.

At the same time the fourth – but secret – member of the Triple Alliance, Romania, was warning that it would not be able to meet its obligations to assist Austria. Romanians, the Hohenzollern king advised, were offended by Hungary’s treatment of its Romanian population: they now regarded Austria, not Russia, as their primary enemy. King Karl did not believe the Serbian government was involved in the assassination and complained that the Austrians seemed to have lost their heads. Berlin should exert its influence on Vienna to extinguish the ‘pusillanimous spirit’ there.

By the end of the week Italy had added its voice to the chorus of restraint. The foreign minister, the Marchese di San Giuliano, insisted that governments of democratic countries (such as Serbia) ‘could not be held accountable for the transgressions of the press’. The Austrians should not be unfair, and he was urging moderation on the Serbians. There seemed every reason to believe that peace would endure: the British ambassador in Vienna thought the government would hesitate to take a step that would produce ‘great international tension’, and the Serbian minister there had assured him that he had no reason to expect a ‘threatening communication’ from Austria.

Gordon Martel is a leading authority on war, empire, and diplomacy in the modern age. His numerous publications include studies of the origins of the first and second world wars, modern imperialism, and the nature of diplomacy. A founding editor of The International History Review, he has taught at a number of Canadian universities, and has been a visiting professor or fellow in England, Ireland and Australia. Editor-in-chief of the five-volume Encyclopedia of War, he is also joint editor of the longstanding Seminar Studies in History series. His new book is The Month That Changed The World: July 1914.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only history articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Image credit: Map highlighting the Triple Alliance. By Nydas. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons

The post The month that changed the world: Monday, 6 July to Sunday, 12 July 1914 appeared first on OUPblog.

By: DanP,

on 7/3/2014

Blog:

OUPblog

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

wilfred owen,

war poetry,

The Great War,

john balaban,

jon stallworthy,

new oxford book of war poetry,

stallworthy,

adiuzdccgw8,

dexyjf_dppc,

balaban,

ymhsxz5,

wyton,

Books,

History,

Poetry,

WWII,

Videos,

Vietnam War,

thomas hardy,

soldiers,

iraq war,

America,

Multimedia,

British,

wwi,

first world war,

Second World War,

*Featured,

Add a tag

There can be no area of human experience that has generated a wider range of powerful feelings than war. Jon Stallworthy’s celebrated anthology The New Oxford Book of War Poetry spans from Homer’s Iliad, through the First and Second World Wars, the Vietnam War, and the wars fought since. The new edition, published to mark the centenary of the outbreak of the First World War, includes a new introduction and additional poems from David Harsent and Peter Wyton amongst others. In the three videos below Jon Stallworthy discusses the significance and endurance of war poetry. He also talks through his updated selection of poems for the second edition, thirty years after the first.

Jon Stallworthy examines why Britain and America responded very differently through poetry to the outbreak of the Iraq War.

Click here to view the embedded video.

Jon Stallworthy on his favourite war poems, from Thomas Hardy to John Balaban.

Click here to view the embedded video.

As The New Oxford Book of War Poetry enters its second edition, editor Jon Stallworthy talks about his reasons for updating it.

Click here to view the embedded video.

Jon Stallworthy is a poet and Professor Emeritus of English Literature at Oxford University. He is also a Fellow of the British Academy. He is the author of many distinguished works of poetry, criticism, and translation. Among his books are critical studies of Yeats’s poetry, and prize-winning biographies of Louis MacNiece and Wilfred Owen (hailed by Graham Greene as ‘one of the finest biographies of our time’). He has edited and co-edited numerous anthologies, including the second edition of The New Oxford Book of War Poetry.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via

email or

RSS.

Subscribe to only history articles on the OUPblog via

email or

RSS.

The post What can poetry teach us about war? appeared first on OUPblog.

By: Kirsty,

on 6/30/2014

Blog:

OUPblog

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

British,

wwi,

first world war,

UK politics,

margot,

*Featured,

UKpophistory,

eleanor brock,

herbert henry asquith,

margot asquith,

margot asquith's diary. great war,

mark pottle,

michael brock,

asquith,

brock,

lászló,

History,

Biography,

Politics,

Current Affairs,

Add a tag

Margot Asquith was the opinionated and irrepressible wife of Herbert Henry Asquith, the Liberal Prime Minister who led Britain into war on 4 August 1914. With the airs, if not the lineage, of an aristocrat, Margot knew everyone, and spoke as if she knew everything, and with her sharp tongue and strong views could be a political asset, or a liability, almost in the same breath. Her Great War diary is by turns revealing and insightful, funny and poignant, and it offers a remarkable view of events from her vantage point in 10 Downing Street. The diary opens with Margot witnessing the scene in the House of Commons, as the political crisis over Irish Home Rule began to be eclipsed by the even greater crisis of the threat of a European war, in which Britain might become involved…

Friday 24 July 1914

The gallery was packed, Ly Londonderry and the Diehards sitting near Mrs Lowther—myself and Liberal ladies the other side of the gallery. The beautiful, incredibly silly Muriel Beckett and M. Lowther rushed round me, and others, pressing up, said ‘Good Heavens, Margot, what does this mean? How frightfully dangerous! Why, the Irish will be fighting tonight—what does it all mean?’ M. ‘It means your civil war is postponed, and you will, I think, never get it.’ I looked at these women who had been insolent to me all the session, when I added ‘If you read the papers, you’ll find we are on the verge of a European war.’

Redmond told H. that afternoon that if the Government liked to remove every soldier from Ireland, he would bet there would never be one hitch; and that both his volunteers and Carson’s would police Ireland with ease.

War! War!—everyone at dinner discussing how long the war would last. The average opinion was 3 weeks to 3 months. Violet said 4 weeks. H. said nothing, which amazed us! I said it would last a year. I went to tea with Con, and Betty Manners told me she had heard Kitchener at lunch say to Arthur Balfour he was sure it would last over a year.

Wednesday 29 July 1914

Bad news from abroad. I was lying in bed, resting, 7.30 p.m. The strain from hour to hour waiting for telegrams, late at night; standing stunned and unable to read or write; two cabinets a day; crowds through which to pass, cheering Henry wildly—all this contributed to making me tired. H. came into my room. I saw by his face that something momentous had happened. I sat up and looked at him. For once he stood still, and didn’t walk up and down the room (He never sits down when he is talking of important things.)

H. Well! We’ve sent what is called ‘the precautionary telegram’ to every office in the Empire—War, Navy, Post Office, etc., to be ready for war. This is what the Committee of Defence have been discussing and settling for the last two years. It has never been done before, and I am very curious to see what effect it will have. All these wires were sent between 2 and 2.30 marvellously quick. (I never saw Henry so keen outwardly—his face looked quite small and handsome. He sat on the foot of my bed.)

M. (passionately moved, I sat up, and felt 10 feet high.) How thrilling! Oh! Tell me, aren’t you excited, darling?

H. (who generally smiles with his eyebrows slightly turned, quite gravely kissed me, and said) It will be very interesting.

Margot Asquith’s Great War Diary 1914-1916 is selected and edited by Michael Brock and Eleanor Brock. Until his death in April 2014, Michael Brock was a modern historian, educationalist, and Oxford college head; he was Vice-President of Wolfson College; Director of the School of Education at Exeter University; Warden of Nuffield College, Oxford; and Warden of St George’s House, Windsor Castle; he is the author of The Great Reform Act, and co-editor, with Mark Curthoys, of the two nineteenth-century volumes in the History of the University of Oxford. With his wife, Eleanor Brock, a former schoolteacher, he edited the acclaimed OUP edition H. H. Asquith: Letters to Venetia Stanley.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only history articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Image credit: Margot Asquith. By Philip de László. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons

The post Margot Asquith’s Great War diary appeared first on OUPblog.

By: Kirsty,

on 6/29/2014

Blog:

OUPblog

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

wwi,

World War One,

first world war,

*Featured,

UKpophistory,

gordon martel,

july 1914,

the month that changed the world,

july crisis,

Books,

History,

military history,

World,

British,

This Day in History,

Europe,

Add a tag

July 1914 was the month that changed the world. On 28 June 1914, Archduke Franz Ferdinand was assassinated, and just five weeks later the Great Powers of Europe were at war. But how did it all happen? Historian Gordon Martel, author of The Month That Changed The World: July 1914, is blogging regularly for us over the next few weeks, giving us a week-by-week and day-by-day account of the events that led up to the First World War.

By Gordon Martel

Although it was Sunday, news of the assassination rocketed around the capitals of Europe. By evening Princip and Čabrinović had been arrested, charged, taken to the military prison and put in chains. All of Čabrinović’s family had been rounded up and arrested, along with those they employed in the family café; Ilić was arrested that afternoon. The remaining conspirators fled the city but within days six of the seven had been captured.

On Sunday evening crowds of young Croatian and Muslim men gathered and marched through Sarajevo, singing the Bosnian anthem and shouting ‘Down with the Serbs’. About one hundred of them stoned the Hotel Europa, owned by a prominent Serb and frequented by Serbian intellectuals. The next morning Croat and Muslim leaders held a rally to demonstrate their support for Austrian rule. They sang the national anthem of the monarchy and carried portraits of the emperor. Sporadic demonstrations quickly escalated into full-scale rioting. Crowds began smashing windows of Serbian businesses and institutions, ransacking the Serbian school, stoning the residence of the head of the Serbian Orthodox Church in Sarajevo and besieging the homes of prominent Serbs.

The people of Vienna had remained calm when news of the assassination arrived on Sunday, but by Monday afternoon a crowd gathered at the Serbian legation and police had to be called in. Behind the scenes the chief of Austria-Hungary’s general staff argued that they must ‘draw the sword’ against Serbia. Leading Viennese newspapers however argued against a campaign of revenge. The emperor returned to Vienna from his hunting lodge on Monday, blaming himself for the killings: God was punishing him for permitting Franz Ferdinand’s marriage to Sophie.

By Tuesday the Austro-Hungarian foreign minister, Count Berchtold, was convinced that the conspiracy had been planned in Belgrade. But what would he propose to do? Would he agree to ‘draw the sword’ against Serbia? Or might he be satisfied with Serbian promises to act against those involved in the conspiracy? His choice would rest largely upon the advice he received from his German allies: he could not risk war without German support.

Austro-Hungarian foreign minister, Count Berchtold, public domain

The German ambassador in Vienna preached restraint. Meeting with Berchtold on Tuesday, Heinrich von Tschirschky advised him not to act in haste, to first decide exactly what he wished to achieve and to weigh his options carefully. Neither of their other allies – Italy and Romania – were likely to support an energetic response. In Berlin, a leading official at the Wilhelmstrasse (the German foreign office), confided to the Italian ambassador his fear that the Austrians might adopt ‘severe and provocative’ measures and that Germany would be faced with the task of restraining them.

On Wednesday Serbia’s prime minister instructed his representatives to explain that his government had taken steps to suppress anarchic elements within Serbia, and that it would now redouble its vigilance and take the severest measures against them: ‘Serbia will do everything in her power and use all the means at her disposal in order to restrain the feelings of ill-balanced people within her frontiers.’

Might this satisfy the Austrians? Ambassador Tschirschky could not envision them demanding more than that Serbia should cooperate in an investigation into the assassination. At the same time, the Hungarian minister-president, István Tisza, was urging the emperor not to use the assassination as an excuse for a ‘reckoning’ with Serbia: it could be fatal to proceed without proof that the Serbian government had been complicit in the plot.

Few expected Count Berchtold to act decisively. He was widely regarded as intelligent but weak, charming but cautious. No one expected him to undertake anything adventurous, and he now appeared to fulfil these expectations. Before making any crucial decisions Berchtold revised an existing memorandum that advised how to meet the growing threat of Russia in the Balkans and turned it into a plea for German support in Austria’s coercion of Serbia. He then drafted a ‘personal’ letter to be sent from the emperor to the kaiser. On Thursday Franz Joseph wrote the letter in his own hand: the crime committed against his nephew (no mention of the duchess) had resulted directly from the agitation conducted by ‘Russian and Serbian Panslavists’ who were determined to weaken the Triple Alliance and ‘shatter my empire’. The Serbian government aimed to unite all south-Slavs under the Serbian flag, which was a lasting danger ‘to my house and to my countries’.

By Thursday a preliminary police investigation had identified seven principal conspirators. Six of them had been taken into custody. Interrogations of the prisoners already indicated that they could be linked to highly-placed officials in Belgrade. And the Austrian military attaché in Belgrade was sending reports linking the conspiracy to Serbian army officers and to the Narodna Odbrana. The pieces of the puzzle seemed to be fitting into place. That evening the bodies of the archduke and the duchess arrived in Vienna; they were to lie in state at the Hofburg Palace until a requiem mass was said on Saturday. They would then be transported to their final resting-place in the chapel Franz Ferdinand had built for that purpose at his castle in Artstetten.

The politicians and diplomats of the so-called Triple Entente – France, Russia, and Britain – expressed few fears of an impending international crisis in the week following the assassination. When the French cabinet met following the assassination on Tuesday the situation arising from Sarajevo was barely mentioned. The French ambassador in Vienna believed the emperor would restrain those seeking revenge and that Austria was not likely to go beyond making threats. The Russian ambassador agreed: he did not believe that the Austrian government would allow itself to be rushed into a war for which it was not prepared. In London, the permanent under-secretary of state at the Foreign Office doubted that Austria would undertake any ‘serious’ action.

While Entente diplomats were comforting themselves with the thought that Austria would not go beyond words, Berchtold despatched his chef de cabinet, Count Hoyos, to Berlin. He carried with him the emperor’s letter to the kaiser and the long memorandum on the Balkan situation that the foreign minister had revised for the purpose. Hoyos, one of the ‘young rebels’ at the Ballhausplatz (the Austrian foreign office), advocated an aggressive foreign policy as an antidote to the monarchy’s apparent decline. Before leaving for Berlin he told a German journalist that he believed Austria must seize the opportunity to ‘solve’ the Serbian problem. It would be most valuable if Germany promised to ‘cover our rear’.

In Berlin on Sunday 5 July 1914 the Germans seemed prepared to do just that. Although the Kaiser expressed his concern that severe measures against Serbia might lead to serious complications he promised that Austria could rely upon the full support of Germany. He did not believe that the Russians were prepared for war, but even if it came to this he assured the Austrian ambassador that Germany would ‘stand at our side’ and that it would be regrettable if Austria failed to seize the moment ‘which is so favourable to us.’ This would go down in legend as the ‘blank cheque’.

Gordon Martel is a leading authority on war, empire, and diplomacy in the modern age. His numerous publications include studies of the origins of the first and second world wars, modern imperialism, and the nature of diplomacy. A founding editor of The International History Review, he has taught at a number of Canadian universities, and has been a visiting professor or fellow in England, Ireland and Australia. Editor-in-chief of the five-volume Encyclopedia of War, he is also joint editor of the longstanding Seminar Studies in History series. His new book is The Month That Changed The World: July 1914.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only history articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Image credit: Count Leopold Berchtold. By Philip de László. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons

The post The month that changed the world: Monday, 29 June to Sunday, 5 July 1914 appeared first on OUPblog.

By: Kirsty,

on 6/28/2014

Blog:

OUPblog

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

Books,

History,

military history,

World,

This Day in History,

Europe,

wwi,

World War One,

first world war,

assassination,

bosnia,

Serbia,

*Featured,

UKpophistory,

Archduke Franz Ferdinand,

gordon martel,

july 1914,

the month that changed the world,

july crisis,

appel quay,

Count Harrach,

Fehim Effendi Čurćić,

Gavrilo Princip,

General Potiorek,

Nedeljko Čabrinović,

sajajevo,

princip,

appel,

quay,

potiorek,

archduke,

Add a tag

July 1914 was the month that changed the world. On 28 June 1914, Archduke Franz Ferdinand was assassinated, and just five weeks later the Great Powers of Europe were at war. But how did it all happen? Historian Gordon Martel, author of The Month That Changed The World: July 1914, is blogging regularly for us over the next few weeks, giving us a week-by-week and day-by-day account of the events that led up to the First World War.

By Gordon Martel

At 10 a.m. that morning the royal party arrived at the railway station. A motorcade consisting of six automobiles was to proceed from there along the Appel Quay to the city hall.The first automobile was to be manned by four special security detectives assigned to guard the archduke, but only one of them managed to take his place; local policemen substituted for the others. The next car was to carry the mayor, Fehim Effendi Čurćić, wearing his red fez, and the chief of police, Dr Edmund Gerde – who had warned the military authorities about the dangerous atmosphere in Sarajevo and had advised against proceeding with the visit.

The archduke and the duchess were seated next to one another in the third car, facing General Potiorek (the military governor of Bosnia) and the owner of the limousine, Count Harrach. The archduke and duchess conducted a brief inspection of the military barracks before setting out for the city hall, where they were to be formally welcomed before proceeding to open the new state museum, designed to display the benefits of Austrian rule.

Seven would-be assassins mingled with the gathering crowds for over an hour before the motorcade arrived. Ilić had assigned one of them, Nedeljko Čabrinović, a place across the street from two others stationed in front of the garden at the Mostar Café, situated near the first bridge on the route, the Čumurja. Ilić and another assassin took their places on the other side of the street; Gavrilo Princip was placed 200 yards further along the route, at the Lateiner bridge. All seven were in place when the royal party arrived at the station that morning.

The arrest of Gavrilo Princip

Ten minutes before the motorcade reached the Čumurja bridge a policeman approached Čabrinović, demanding that he identify himself. He produced a permit that purported to have been issued by the Viennese police and asked the policeman which car was carrying the archduke. ‘The third’ he was told. A few minutes later he took out his grenade, knocked off the detonator cap and threw it at the limousine carrying the archduke and the duchess. Because there was a twelve-second delay between knocking off the cap and the explosion, the grenade hit the limousine, bounced off, rolled under the next car, and exploded. General Potiorek’s aide-de-camp was injured, along with several spectators. The duchess suffered a slight wound to her cheek, where she had been grazed by the grenade’s detonator.

Čabrinović swallowed his cyanide capsule and jumped over the embankment into the river. But the cyanide failed and the river had been reduced to a mere trickle in mid-summer. He was captured immediately by a policeman who asked him if he was a Serb. ‘Yes, I am a Serb hero’, he replied.

The procession continued on its way to the splendid new city hall, the neo-Moorish Vijećnica, meant to evoke the Alhambra as part of Austria’s ‘neo-Orientalist’ policy designed to cultivate the support of Bosnia’s Muslims. When the royal party arrived, the mayor began to read the effusive speech he had prepared in their honour – apparently unaware of the near calamity that had just occurred. The archduke interrupted, angrily demanding to know how the mayor could speak of ‘loyalty’ to the crown when a bomb had just been thrown at him. The duchess, playing her accustomed role, managed to calm him down while they waited for a staff officer to arrive with a copy of the archduke’s speech – which was now splattered in blood.

After the speeches and a reception General Potiorek proposed that they either drive back along the Appel Quay at full speed to the station or go straight to his residence, only a few hundred metres away, and where lunch awaited them. But the archduke insisted on first visiting the wounded officer at the military hospital. The duchess insisted on accompanying him: ‘It is in time of danger that you need me.’

The royal couple, along with Potiorek, climbed into a new car, with Count Harrach standing on the footboard to shield the archduke from any other would-be assassins. A first car, with the chief of police and others, was to precede them. In order to reach the hospital the motorcade was forced to retrace its route along the Appel Quay. Princip, who had almost abandoned hopeafter Čabrinović’s arrest, was still waiting near the Lateiner bridge when the two cars unexpectedly appeared in front of him.

The driver of the first car had turned right off the Appel Quay, following the original route to take them to the museum; the driver of the second car followed him. General Potiorek, immediately recognizing the mistake, ordered his driver to stop. The car then began to reverse slowly in order to get back onto the Appel Quay – with Count Harrach now on the opposite side of the car to Princip, who was standing at the corner of Appel Quay and Franz Joseph Street, in front of Schiller’s delicatessen. Seizing the opportunity, Princip stepped out of the crowd. His moment had arrived.

Because it was too difficult to take the grenade out of his coat and knock off the detonator cap, Princip decided to use his revolver instead. A policeman spotted him and tried to intervene, but a friend of Princip’s kicked the policeman in the knee and knocked him off balance. The first shot hit the archduke near the jugular vein; the second hit the duchess in the stomach. ‘Soferl, Soferl!’ Franz Ferdinand cried, ‘Don’t die. Live for our children.’ The duchess was already dead by the time they reached the governor’s residence. The archduke, unconscious when he was carried inside, was also dead within minutes – before either a doctor or a priest could be summoned.

Spectators were attempting to lynch Princip when the police rescued him. He tried to swallow the cyanide capsule, but vomited it up. An Austrian judge, interviewing him almost immediately afterwards, wrote: ‘The young assassin, exhausted by his beating, was unable to utter a word. He was undersized, emaciated, sallow, sharp featured. It was difficult to imagine that so frail looking an individual could have committed so serious a deed.’

Gordon Martel is a leading authority on war, empire, and diplomacy in the modern age. His numerous publications include studies of the origins of the first and second world wars, modern imperialism, and the nature of diplomacy. A founding editor of The International History Review, he has taught at a number of Canadian universities, and has been a visiting professor or fellow in England, Ireland and Australia. Editor-in-chief of the five-volume Encyclopedia of War, he is also joint editor of the longstanding Seminar Studies in History series. His new book is The Month That Changed The World: July 1914.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only history articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Image credit: Princip arrest [public domain]. Via Wikimedia Commons.

The post The month that changed the world: Sunday, 28 June 1914 appeared first on OUPblog.

By: Kirsty,

on 6/27/2014

Blog:

OUPblog

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

Serbia,

Sarajevo,

Editor's Picks,

*Featured,

UKpophistory,

Archduke Franz Ferdinand,

gordon martel,

july 1914,

the month that changed the world,

july crisis,

History,

military history,

World,

world war I,

This Day in History,

Europe,

wwi,

World War One,

first world war,

bosnia,

Add a tag

July 1914 was the month that changed the world. On 28 June 1914, Archduke Franz Ferdinand was assassinated, and just five weeks later the Great Powers of Europe were at war. But how did it all happen? Historian Gordon Martel, author of The Month That Changed The World: July 1914, will be blogging regularly for us over the next few weeks, giving us a week-by-week and day-by-day account of the events that led up to the First World War. His first post focuses on the events of Saturday, 27 June 1914.

By Gordon Martel

The next day was to be a brilliant one, a splendid occasion that would glorify the achievements of Austrian rule in Bosnia-Herzegovina. The Habsburg heir to the thrones of Austria and Hungary, the Archduke Franz Ferdinand, had been eagerly anticipating it for months. He envisioned making a triumphal entry into the city of Sarajevo, attired in his uniform as inspector-general of the Austro-Hungarian army, and accompanied by his wife, the duchess. Sophie would be resplendent in a full-length white dress with red sash tied at the waist, she would hold a parasol to shelter from the sun and a fan to cool her; gloves, furs and a magnificent hat would complete the outfit.

The date of Sunday, 28 June had been chosen carefully: it was the anniversary of the battle of Kosovo in 1389, at which the medieval Serbian kingdom had been extinguished by the victorious Turks. Afterwards, Bosnia and Herzegovina remained provinces of the Ottoman empire for almost 500 years, until occupied by Austro-Hungarian forces in 1878 and then annexed in 1908. Thus, on the occasion of the archduke’s visit, the Serbs of Bosnia were asked to pay homage to a member of the royal family that blocked the way to uniting all Serbs in a Greater Serbia. The location was also provocative: the archducal visit to Sarajevo was preceded by military manoeuvres in the mountains south of the city – not far from the frontier with Serbia.

The Austrians disregarded warnings of trouble. The Serbian minister in Vienna had suggested to the minister responsible for Bosnian affairs that some Serbs might regard the time and place of the visit as a deliberate affront. Perhaps, he warned, some young Serb participating in the Austrian manoeuvres might substitute live ammunition for blanks – and seize the opportunity to fire at the archduke. Politicians and officials on the spot in Sarajevo had advised that the visit be cancelled; the police warned that they could not guarantee the archduke’s safety, particularly given the lengthy route that that the royal couple were scheduled to take along the Miljačka river from the railway station to the city hall.

Archduke Franz Ferdinand