|

| The Death of Captain Miller in Saving Private Ryan |

|

| The Death of Captain Miller in Saving Private Ryan |

The privileged poets of the Great War are those who fought in it—Rosenberg, Owen, Sassoon. This is natural and human, but it is not fair. Kipling is one of the finest poets of the War, but he writes as a parent, a civilian, a survivor—all three of them compromised positions.

The post “Our fathers lied”: Rudyard Kipling as a war poet appeared first on OUPblog.

A couple of months ago I revisited an iconic song by Eric Bogle, finding new breath in Bruce Whatley’s picture book, And the Band Played Waltzing Matilda. Bogle found the words and Whatley the images that profoundly capture all the raw emotion, loss and resilience that epitomises the Great War of 100 years ago. This […]

Add a Comment

By December 1914 the Great War had been raging for nearly five months. If anyone had really believed that it would be ‘all over by Christmas’ then it was clear that they had been cruelly mistaken. Soldiers in the trenches had gained a grudging respect for their opposite numbers. After all, they had managed to fight each other to a standstill.

On Christmas Eve there was a severe frost. From the perspective of the freezing-cold trenches the idea of the season of peace and goodwill seemed surrealistic. Yet parcels and Christmas gifts began to arrive in the trenches and there was a strange atmosphere in the air. Private William Quinton was watching:

We could see what looked like very small coloured lights. What was this? Was it some prearranged signal and the forerunner of an attack? We were very suspicious, when something even stranger happened. The Germans were actually singing! Not very loud, but there was no mistaking it. Suddenly, across the snow-clad No Man’s Land, a strong clear voice rang out, singing the opening lines of “Annie Laurie“. It was sung in perfect English and we were spellbound. To us it seemed that the war had suddenly stopped! Stopped to listen to this song from one of the enemy.

“We tied an empty sandbag up with its string and kicked it about on top – just to keep warm of course. We did not intermingle.”

On Christmas Day itself, in some sectors of the line, there was no doubting the underlying friendly intent. Yet the men that took the initiative in initiating a truce were brave – or foolish – as was witnessed by Sergeant Frederick Brown:

Sergeant Collins stood waist high above the trench waving a box of Woodbines above his head. German soldiers beckoned him over, and Collins got out and walked halfway towards them, in turn beckoning someone to come and take the gift. However, they called out, “Prisoner!” A shot rang out, and he staggered back, shot through the chest. I can still hear his cries, “Oh my God, they have shot me!”

This was not a unique incident. Yet, despite the obvious risks, men were still tempted. Individuals would get off the trench, then dive back in, gradually becoming bolder as Private George Ashurst recalled:

It was grand, you could stretch your legs and run about on the hard surface. We tied an empty sandbag up with its string and kicked it about on top – just to keep warm of course. We did not intermingle. Part way through we were all playing football. It was so pleasant to get out of that trench from between them two walls of clay and walk and run about – it was heaven.

The idea that football matches were played between the British and Germans in No Man’s Land has taken a grip, but the evidence is intangible.

The truce was not planned or controlled – it just happened. Even senior officers recognised that there was little that could be done in this strange state of affairs. Brigadier General Lord Edward Gleichen accepted the truce as a fait accompli, but was keen to ensure that the Germans did not get too close to the ramshackle British trenches:

They came out of their trenches and walked across unarmed, with boxes of cigars and seasonable remarks. What were our men to do? Shoot? You could not shoot unarmed men. Let them come? You could not let them come into your trenches; so the only thing feasible was done – and our men met them half-way and began talking to them. Meanwhile our officers got excellent close views of the German trenches.

Another practical reason for embracing the truce was the opportunity it presented for burying the dead that littered No Man’s Land. Private Henry Williamson was assigned to a burial party:

The Germans started burying their dead which had frozen hard. Little crosses of ration box wood nailed together and marked in indelible pencil. They were putting in German, ‘For Fatherland and Freedom!’ I said to a German, “Excuse me, but how can you be fighting for freedom? You started the war, and we are fighting for freedom!” He said, “Excuse me English comrade, but we are fighting for freedom for our country!”

It should be noted that the truce was by no means universal, particularly where the British were facing Prussian units.

For the vast majority of the participants, the truce was a matter of convenience and maudlin sentiment. It did not mark some deep flowering of the human spirit, or signify political anti-war emotions taking root amongst the ranks. The truce simply enabled them to celebrate Christmas in a freer, more jovial, and, above all, safer environment, while satisfying their rampant curiosity about their enemies.

The truce could not last: it was a break from reality, not the dawn of a peaceful world. The gradual end mirrored the start, for any misunderstandings could cost lives amongst the unwary. For Captain Charles Stockwell it was handled with a consummate courtesy:

At 8.30am I fired three shots in the air and put up a flag with ‘Merry Christmas!’ on it, and I climbed on the parapet. He put up a sheet with, ‘Thank you’ on it, and the German captain appeared on the parapet. We both bowed and saluted and got down into our respective trenches – he fired two shots in the air and the war was on again!

In other sectors, the artillery behind the lines opened up and the bursting shells soon shattered the truce.

War regained its grip on the whole of the British sector. When it came to it, the troops went back to war willingly enough. Many would indeed have rejoiced at the end of the war, but they were still willing to accept orders, still willing to kill Germans. Nothing had changed.

The post The Christmas truce: A sentimental dream appeared first on OUPblog.

As the first year of the World War I centenary continues, here is a selection of classic literature inspired by the conflict. Some of it was written in the years after the war, while some of it was completed as the conflict was in progress. What they all have in common, though, is an unflinchingly expression of the horrors of the First World War for those in the thick of the battles, and those left behind at home.

The Poetry of the First World War, edited by Tim Kendall

The First World War brought forth an extraordinary amount of poetic talent. Their poems have come to express the feelings of a nation about the horrors of war. Some of these poets are widely read and studied to this day, such as Wilfred Owen, Siegfried Sassoon, Rupert Brooke, and Ivor Gurney. However, others are less widely read, and this anthology incorporates that writing with work by civilian and woman poets, along with music hall and trench songs.

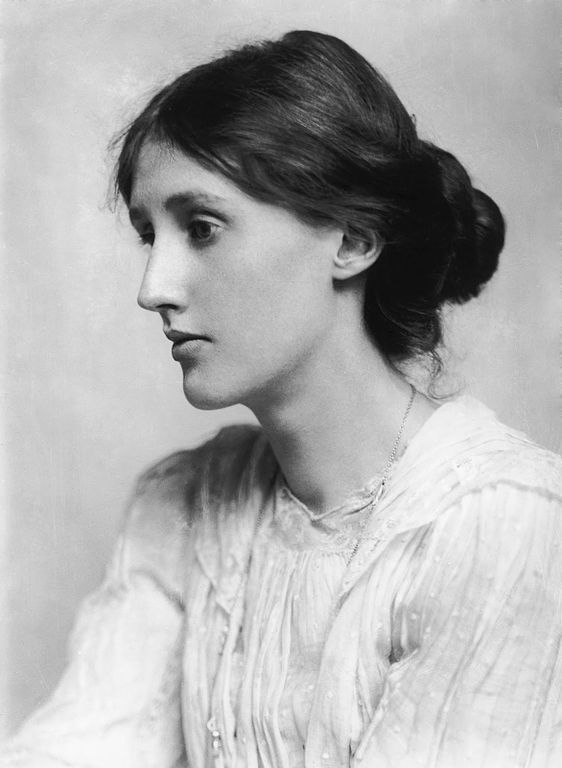

Mrs Dalloway by Virginia Woolf

This, Woolf’s fourth novel, prominently features Septimus Warren Smith, a young man deeply damaged by his time in the First World War. Shellshock causes him to hallucinate – he thinks he hears birds in a park chattering in Greek, for instance – and the psychological toll wrought by war drives him to a profound hatred of himself and the whole human race.

The Good Soldier by Ford Madox Ford

Ford Madox Ford was in the process of writing The Good Soldier when the First World War broke out in 1914. Inevitably this influenced his work, and this novel brilliantly portrays the destruction of a civilized elite as it anticipates the cataclysm of war. It also invokes contemporary concerns about sexuality, psychoanalysis, and the New Woman.

Greenmantle by John Buchan

In Greenmantle – published during the First World War, in 1916 – Richard Hannay travels across Europe as it is being torn apart by war. He is in search of a German plot and an Islamic Messiah, and is in the process joined by three more of Buchan’s heroes: old Boer Scout Peter Pienaar; John S. Blenkiron, an American determined to fight the Kaiser; and Sandy Arbuthnot, Greenmantle himself, who was modelled on Lawrence of Arabia. In this rip-roaring tale Buchan shows his mastery of the thriller and of the Stevensonian romance, and also his enormous knowledge of international politics before and during World War I.

Jacob’s Room by Virginia Woolf

This is Virginia Woolf’s third novel, and was published in 1922. It is an experimental portrait of Jacob Flanders, a young man who is both representative and victim of the social values which led Edwardian society into the First World War. Even his very name indicates his position as the archetypal victim of the war: Flanders is an area of Belgium where many British soldiers were killed and injured during the First World War. Jacob’s Room is an experimental novel, cutting back and forth in time, and never quite allowing the reader full sight of its subject. Rather, Jacob’s story is told through the words and memories of the women in his life.

War Stories and Poems by Rudyard Kipling

Rudyard Kipling may be most commonly remembered for the Just So Stories and The Jungle Book, but he also wrote extensively about war. His only son, John, was unfortunately killed in action in 1915, and Kipling took many years to accept what had happened. Until his death in 1936, he continued searching for his son’s final resting place but even today John has no known grave. Of the poems Kipling wrote in the aftermath of the First World War, perhaps the best known is his tribute to The Irish Guards (1918), the regiment with which his son was serving at the time of his death.

Headline image credit: World War One soldier’s diary pages. Photo by lawcain via iStockphoto.

The post A First World War reading list from Oxford World’s Classics appeared first on OUPblog.

The horror of the First World War produced an extraordinary amount of poetry, both during the conflict and in reflection afterwards. Professor Tim Kendall’s anthology, Poetry of the First World War, brings together work by many of the well-known poets of the time, along with lesser-known writing by civilian and women poets and music hall and trench songs.

This is a poem from that anthology, ‘Song of Amiens’ by T. P. Cameron Wilson. Wilson had been a teacher until war broke out, when he enlisted. He served with the Sherwood Foresters, and was killed during the great German assault of March 1918.

Song of Amiens

Lord! How we laughed in Amiens!

For here were lights and good French drink,

And Marie smiled at everyone,

And Madeleine’s new blouse was pink,

And Petite Jeanne (who always runs)

Served us so charmingly, I think

That we forgot the unsleeping guns.

Lord! How we laughed in Amiens!

Till through the talk there flashed the name

Of some great man we left behind.

And then a sudden silence came,

And even Petite Jeanne (who runs)

Stood still to hear, with eyes aflame,

The distant mutter of the guns.

Ah! How we laughed in Amiens!

For there were useless things to buy,

Simply because Irène, who served,

Had happy laughter in her eye;

And Yvonne, bringing sticky buns,

Cared nothing that the eastern sky

Was lit with flashes from the guns.

And still we laughed in Amiens,

As dead men laughed a week ago.

What cared we if in Delville Wood

The splintered trees saw hell below?

We cared . . . We cared . . . But laughter runs

The cleanest stream a man may know

To rinse him from the taint of guns.

- T. P. Cameron Wilson (1888-1918)

Featured image: 8th August, 1918 by Will Longstaff, Australian official war artist. Depicts a scene during the Battle of Amiens. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

The post Song of Amiens appeared first on OUPblog.

To mark the outbreak of the First World War, this week’s Very Short Introductions blog post is an extract from The First World War: A Very Short Introduction, by Michael Howard. The extract below describes the public reaction to the outbreak of war, the government propaganda in the opening months, and the reasons behind each nation going to war.

The outbreak of war was greeted with enthusiasm in the major cities of all the belligerent powers, but this urban excitement was not necessarily typical of public opinion as a whole. The mood in France in particular was one of stoical resignation – one that probably characterized all agrarian workers who were called up and had to leave their land to be cultivated by women and children. But everywhere peoples were supportive of their governments. This was no ‘limited war’ between princely states. War was now a national affair. For a century past, national self-consciousness had been inculcated by state educational programmes directed to forming loyal and obedient citizens. Indeed, as societies became increasingly secular, the concept of the Nation, with all its military panoply and heritage, acquired a quasi-religious significance. Conscription assisted this indoctrination process but was not essential to it: public opinion in Britain, where conscription was not introduced until 1916, was as keenly nationalistic as anywhere on the Continent. For thinkers saturated in Darwinian theory, war was seen as a test of ‘manhood’ such as soft urban living no longer afforded. Such ‘manhood’ was believed to be essential if nations were to be ‘fit to survive’ in a world where progress was the result, or so they believed, of competition rather than cooperation, between nations as between species. Liberal pacifism remained influential in Western democracies, but it was also widely seen, especially in Germany, as a symptom of moral decadence.

Such sophisticated belligerence made the advent of war welcome to many intellectuals, as well as to members of the old ruling classes, who accepted with enthusiasm their traditional function of leadership in war. Artists, musicians, academics, and writers vied with each other in offering their services to their governments. For artists in particular, Futurists in Italy, Cubists in France, Vorticists in Britain, Expressionists in Germany, war was seen as an aspect of the liberation from an outworn regime that they themselves had been pioneering for a decade past. Workers in urban environments looked forward to finding in it an exciting and, they hoped, a brief respite from the tedium of their everyday lives. In the democracies of Western Europe mass opinion, reinforced by government propaganda, swept along the less enthusiastic. In the less literate and developed societies further east, traditional feudal loyalty, powerfully reinforced by religious sanctions, was equally effective in mass mobilization.

Crowds outside Buckingham Palace cheer King George, Queen Mary and the Prince of Wales following the Declaration of War in August 1914. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.

And it must be remembered that all governments could make out a plausible case. The Austrians were fighting for the preservation of their historic multinational empire against disintegration provoked by their old adversary Russia. The Russians were fighting for the protection of their Slav kith and kin, for the defence of their national honour, and to fulfil their obligations to their ally France. The French were fighting in self-defence against totally unprovoked aggression by their traditional enemy. The British were fighting to uphold the law of nations and to pre-empt the greatest threat they had faced from the Continent since the days of Napoleon. The Germans were fighting on behalf of their one remaining ally, and to repel a Slavic threat from the east that had joined forces with their jealous rivals in the west to stifle their rightful emergence as a World Power. These were the arguments that governments presented to their peoples. But the peoples did not have to be whipped up by government propaganda. It was in a spirit of simple patriotic duty that they joined the colours and went to war.

Writing at the end of the nineteenth century the German military writer Colmar von der Goltz had warned that any future European war would see ‘an exodus of nations’, and he was proved right. In August 1914 the armies of Europe mobilized some six million men and hurled them against their neighbours. German armies invaded France and Belgium. Russian armies invaded Germany. Austrian armies invaded Serbia and Russia. French armies attacked over the frontier into German Alsace-Lorraine. The British sent an expeditionary force to help the French, confidently expecting to reach Berlin by Christmas. Only the Italians, whose obligations under the Triple Alliance covered only a defensive war and ruled out incurring British hostility, prudently waited on events. If ‘the Allies’ (as the Franco-Russo-British alliance became generally known) won, Italy might gain the lands she claimed from Austria; if ‘the Central Powers’ (the Austro-Germans), she might win not only the contested borderlands with France, Nice and Savoy, but French possessions in North Africa to add to the Mediterranean empire she had already begun to acquire at the expense of the Turks. Italy’s policy was guided, as their Prime Minister declared with endearing frankness, by sacro egoismo.

This extract was taken from The First World War: A Very Short Introduction, by Michael Howard. The Very Short Introductions (VSI) series combines a small format with authoritative analysis and big ideas for hundreds of topic areas. Written by our expert authors, these books can change the way you think about the things that interest you and are the perfect introduction to subjects you previously knew nothing about. Grow your knowledge with OUPblog and the VSI series every Friday, subscribe to Very Short Introductions articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS, and like Very Short Introductions on Facebook.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS

Subscribe to only history articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

The post 1914: The opening campaigns appeared first on OUPblog.

July 1914 was the month that changed the world. On 28 June 1914, Archduke Franz Ferdinand was assassinated, and just five weeks later the Great Powers of Europe were at war. But how did it all happen? Historian Gordon Martel, author of The Month That Changed The World: July 1914, is blogging regularly for us over the past few weeks, giving us a week-by-week and day-by-day account of the events that led up to the First World War.

The choice between war and peace hung in the balance on Saturday, 1 August 1914. Austria-Hungary and Russia were proceeding with full mobilization: Austria-Hungary was preparing to mobilize along the Russian frontier in Galicia; Russia was preparing to mobilize along the German frontier in Poland. On Friday evening in Paris the German ambassador had presented the French government with a question: would France remain neutral in the event of a Russo-German war? They were given 18 hours to respond – until 1 p.m. Saturday. In St Petersburg the German ambassador presented the Russian government with another demand: Russia had 12 hours – until noon Saturday – to suspend all war measures against Germany and Austria-Hungary or Germany would mobilize its forces.

But they were also extraordinarily close to peace. Russia and Austria had resumed negotiations in St Petersburg at the behest of Britain, Germany, and France. Austria had declared publicly and repeatedly that it did not intend to seize any Serbian territory and that it would respect the sovereignty and independence of the Serbian monarchy. Russia had declared that it would not object to severe measures against Serbia as long its sovereignty and independence were respected. Surely, when the two of them were agreed on the fundamental principles involved, a settlement was still within reach?

In London the cabinet met at 11 a.m. for 2 1/2 hours. The discussion was devoted exclusively to the crisis. Ministers were badly divided. Winston Churchill was the most bellicose, demanding immediate mobilization. At the other extreme were those who insisted that the government should declare it would not enter the war under any circumstances. According to the prime minister, Asquith, this was ‘the view for the moment of the bulk of the party’. Grey threatened to resign if the cabinet adopted an uncompromising policy of non-intervention.

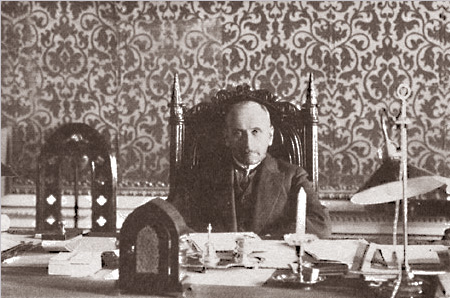

H. H. Asquith, British Prime Minister 1908-1916. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

One cabinet minister proposed a solution to their dilemma: they should put the onus on Germany. Intervention should depend on whether Germany launched a naval attack on the northern coast of France or violated the independence of Belgium. But his suggestion raised more questions: did Britain have the duty, or merely the right, to intervene if Belgian neutrality were violated? If German troops merely ‘passed through’ Belgium in order to attack France, would this constitute a violation of neutrality? The meeting was inconclusive.

In Berlin the Kaiser was approving the note to be handed to Russia later that day, if it failed to respond positively to the demand that it demobilize: ‘His Majesty the Emperor, my August Sovereign, accepts the challenge in the name of the Empire, and considers himself as being in a state of war with Russia’.

An hour after despatching this telegram another arrived in Berlin from the tsar. Nicholas said he understood that, under the circumstances, Germany was obliged to mobilize, but he asked Wilhelm to give him the same guarantee that he had given Wilhelm: ‘that these measures DO NOT mean war’ and that they would continue to negotiate ‘for the benefit of our countries and universal peace dear to our hearts’.

After meeting with the cabinet, Grey continued to believe that peace might be saved if only a little time could be gained before shooting started. He wired Berlin to suggest that mediation between Austria and Russia could now commence. While promising that Britain abstain from any act that might precipitate matters, he refused to promise that it would remain neutral.

But Grey also refused to promise any assistance to France: Germany appeared willing to agree not to attack France if France remained neutral in a war between Russia and Germany. If France was unable to take advantage of this offer ‘it was because she was bound by an alliance to which we were not parties, and of which we did not know the terms’. Although he would not rule out assisting France under any circumstances, France must make its own decision ‘without reckoning on an assistance that we were not now in a position to give’.

The French ambassador was shocked. He refused to transmit to Paris what Grey had told him, proposing instead to tell his government that the British cabinet had yet to make a decision. He complained that France had left its Atlantic coast undefended because of the naval convention with Britain in 1912 and that the British were honour-bound to assist them. His complaint fell on deaf ears. He staggered from Grey’s office into an adjoining room, close to hysteria, ‘his face white’. Immediately after the meeting he met with two influential Unionists, bitterly declaring ‘Honour! Does England know what honour is’? ‘If you stay out and we survive, we shall not move a finger to save you from being crushed by the Germans later.’

Earlier in Paris General Joffre, chief of the general staff, threatened to resign if the government refused to order mobilization. He warned that France had already fallen two days behind Germany in preparing for war. The cabinet, although divided, agreed to distribute mobilization notices that afternoon at 4 p.m. They agreed, however, to maintain the 10-kilometre buffer zone: ‘No patrol, no reconnaissance, no post, no element whatsoever, must go east of the said line. Whoever crosses it will be liable to court martial and it is only in the event of a full-scale attack that it will be possible to transgress this order’.

By 4 p.m. Russia had yet to reply to the German ultimatum that expired at noon. Falkenhayn, the minister of war, persuaded Bethmann Hollweg to go with him to see the Kaiser and ask him to promulgate the order for mobilization. At 5 p.m., at the Berlin Stadtschloss, the mobilization order sat on a table made from the timbers of Nelson’s Victory. As the Kaiser signed it, Falkenhayn declared ‘God bless Your Majesty and your arms, God protect the beloved Fatherland’.

News of the German declaration of war on Russia spread quickly throughout St Petersburg immediately following the meeting between Pourtalès and Sazonov. Vast crowds began to gather on the Nevsky Prospekt; women threw their jewels into collection bins to support the families of the reservists who had been called up. By 11.30 that night around 50,000 people surrounded the British embassy calling out ‘God save the King’, ‘Rule Britannia’, and ‘Bozhe Tsara Khranie’ [God save the Tsar].

Gordon Martel is a leading authority on war, empire, and diplomacy in the modern age. His numerous publications include studies of the origins of the first and second world wars, modern imperialism, and the nature of diplomacy. A founding editor of The International History Review, he has taught at a number of Canadian universities, and has been a visiting professor or fellow in England, Ireland and Australia. Editor-in-chief of the five-volume Encyclopedia of War, he is also joint editor of the longstanding Seminar Studies in History series. His new book is The Month That Changed The World: July 1914.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only history articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

The post The month that changed the world: Saturday, 1 August 1914 appeared first on OUPblog.

July 1914 was the month that changed the world. On 28 June 1914, Archduke Franz Ferdinand was assassinated, and just five weeks later the Great Powers of Europe were at war. But how did it all happen? Historian Gordon Martel, author of The Month That Changed The World: July 1914, is blogging regularly for us over the next few weeks, giving us a week-by-week and day-by-day account of the events that led up to the First World War.

When day dawned on Sunday, 26 July, the sky did not fall. Shells did not rain down on Belgrade. There was no Austrian declaration of war. The morning remained peaceful, if not calm. Most Europeans attended their churches and prepared to enjoy their day of rest. Few said prayers for peace; few believed divine intervention was necessary. Europe had weathered many storms over the last decade. Only pessimists doubted that this one could be weathered as well.

In Austria-Hungary the right of assembly, the secrecy of the mail, of telegrams and telephone conversations, and the freedom of the press were all suspended. Pro-war demonstrations were not only permitted but encouraged: demonstrators filled the Ringstrasse, marched on the Ballhausplatz, gathered around statues of national heroes and sang patriotic songs. That evening the Bürgermeister of Vienna told a cheering crowd that the fate of Europe for centuries to come was about to be decided, praising them as worthy descendants of the men who had fought Napoleon. The Catholic People’s Party newspaper, Alkotmány, declared that ‘History has put the master’s cane in the Monarchy’s hands. We must teach Serbia, we must make justice, we must punish her for her crimes.’

Just how urgent was the situation? In London, Sir Edward Grey had left town on Saturday afternoon to go to his cottage for a day of fly-fishing on Sunday. The Russian ambassadors to Germany, Austria and Paris had yet to return to their posts. The British ambassadors to Germany and Paris were still on vacation. Kaiser Wilhelm was on his annual yachting cruise of the Baltic. Emperor Franz Joseph was at his hunting lodge at Bad Ischl. The French premier and president were visiting Stockholm. The Italian foreign minister was still taking his cure at Fiuggi. The chiefs of the German and Austrian general staffs remained on leave; the chief of the Serbian general staff was relaxing at an Austrian spa.Could calm be maintained? Contradictory evidence seemed to be coming out of St Petersburg. It seemed that some military steps were being initiated – but what these were to be remained uncertain. Sazonov, the Russian foreign minister, met with both the German and Austrian ambassadors on Sunday – and both noted a significant change in his demeanour. He was now ‘much quieter and more conciliatory’. He emphatically insisted that Russia did not desire war and promised to exhaust every means to avoid it. War could be avoided if Austria’s demands stopped short of violating Serbian sovereignty. The German ambassador suggested that Russia and Austria discuss directly a softening of the demands. Sazonov, who agreed immediately to suggest this, was ‘now looking for a way out’. The Germans were assured that only preparatory measures had been undertaken thus far – ‘not a horse and not a reserve had been called to service’.

By late Sunday afternoon, the situation seemed precarious but not hopeless. The German chancellor worried that any preparatory measures adopted by Russia that appeared to be aimed at Germany would force the adoption of counter-measures. This would mean the mobilization of the German army – and mobilization ‘would mean war’. But he continued to hope that the crisis could be ‘localized’ and indicated that he would encourage Vienna to accept Grey’s proposed mediation and/or direct negotiations between Austria and Russia.

By Sunday evening more than 24 hours had passed since the Austrian legation had departed from Belgrade and Austria had severed diplomatic relations with Serbia. Many had assumed that war would follow immediately, but there had been no invasion of Serbia or even a declaration of war. The Austrians, in spite of their apparent firmness in refusing any alteration of the terms or any extension of the deadline, appeared not to know what step to take next, or when additional steps should be taken. When asked, the Austrian chief of staff suggested that any declaration of war ought to be postponed until 12 August. Was Europe really going to hold its breath for two more weeks?

Gordon Martel is a leading authority on war, empire, and diplomacy in the modern age. His numerous publications include studies of the origins of the first and second world wars, modern imperialism, and the nature of diplomacy. A founding editor of The International History Review, he has taught at a number of Canadian universities, and has been a visiting professor or fellow in England, Ireland and Australia. Editor-in-chief of the five-volume Encyclopedia of War, he is also joint editor of the longstanding Seminar Studies in History series. His new book is The Month That Changed The World: July 1914. Read his previous blog posts.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only history articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Image credit: Kaiser Wilhelm, public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

The post The month that changed the world: Sunday, 26 July 1914 appeared first on OUPblog.

July 1914 was the month that changed the world. On 28 June 1914, Archduke Franz Ferdinand was assassinated, and just five weeks later the Great Powers of Europe were at war. But how did it all happen? Historian Gordon Martel, author of The Month That Changed The World: July 1914, is blogging regularly for us over the next few weeks, giving us a week-by-week and day-by-day account of the events that led up to the First World War.

By mid-day Friday heads of state, heads of government, foreign ministers, and ambassadors learned the terms of the Austrian ultimatum. A preamble to the demands asserted that a ‘subversive movement’ to ‘disjoin’ parts of Austria-Hungary had grown ‘under the eyes’ of the Serbian government. This had led to terrorism, murder, and attempted murder. Austria’s investigation of the assassination of the archduke revealed that Serbian military officers and government officials were implicated in the crime.

A list of ten demands followed, the most important of which were: Serbia was to suppress all forms of propaganda aimed at Austria-Hungary; the Narodna odbrana was to be dissolved, along with all other subversive societies; officers and officials who had participated in propaganda were to be dismissed; Austrian officials were to participate in suppressing the subversive movements in Serbia and in a judicial inquiry into the assassination.

When Sazonov saw the terms he concluded that Austria wanted war: ‘You are setting fire to Europe!’ If Serbia were to comply with the demands it would mean the end of its sovereignty. ‘What you want is war, and you have burnt your bridges behind you’. He advised the tsar that Serbia could not possibly comply, that Austria knew this and would not have presented the ultimatum without the promise of Germany’s support. He told the British and French ambassadors that war was imminent unless they acted together.

Sergey Sazonov, public domain via Wikimedia Commons

But would they? With the French president and premier now at sea in the Baltic, and with wireless telegraphy problematic, foreign policy was in the hands of Bienvenu-Martin, the inexperienced minister of justice. He believed that Austria was within its rights to demand the punishment of those implicated in the crime and he shared Germany’s wish to localize the dispute. Serbia could not be expected to agree to demands that impinged upon its sovereignty, but perhaps it could agree to punish those involved in the assassination and to suppress propaganda aimed at Austria-Hungary.

Sir Edward Grey was shocked by the extent of the demands. He had never before seen ‘one State address to another independent State a document of so formidable a character.’ The demand that Austria-Hungary be given the right to appoint officials who would have authority within the frontiers of Serbia could not be consistent with Serbia’s sovereignty. But the British government had no interest in the merits of the dispute between Austria and Serbia; its only concern was the peace of Europe. He proposed that the four ‘disinterested powers’ (Britain, Germany, France and Italy) act together at Vienna and St Petersburg to resolve the dispute. After Grey briefed the cabinet that afternoon, the prime minister concluded that although a ‘real Armaggedon’ was within sight, ‘there seems…no reason why we should be more than spectators’.

Nothing that the Austrians or the Germans heard in London or Paris on Friday caused them to reconsider their course. In fact, their general impression was that the Entente Powers wished to localize the dispute. Even from St Petersburg the German ambassador reported that Sazonov’s reference to Austria’s ‘devouring’ of Serbia meant that Russia would take up arms only if Austria seized Serbian territory and that his wish to ‘Europeanize’ the dispute indicated that Russia’s ‘immediate intervention’ need not be anticipated.

Berchtold made his position clear in Vienna that afternoon: ‘the very existence of Austria-Hungary as a Great Power’ was at stake; Austria-Hungary must give proof of its stature as a Great Power ‘by an outright coup de force’. When the Russian chargé d’affaires asked him how Austria would respond if the time limit were to expire without a satisfactory answer from Serbia, Berchtold replied that the Austrian minister and his staff had been instructed in such circumstances to leave Belgrade and return to Austria. Prince Kudashev, after reflecting on this, exclaimed ‘Alors c’est la guerre!’

Gordon Martel is a leading authority on war, empire, and diplomacy in the modern age. His numerous publications include studies of the origins of the first and second world wars, modern imperialism, and the nature of diplomacy. A founding editor of The International History Review, he has taught at a number of Canadian universities, and has been a visiting professor or fellow in England, Ireland and Australia. Editor-in-chief of the five-volume Encyclopedia of War, he is also joint editor of the longstanding Seminar Studies in History series. His new book is The Month That Changed The World: July 1914.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only history articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

The post The month that changed the world: Friday, 24 July 1914 appeared first on OUPblog.

July 1914 was the month that changed the world. On 28 June 1914, Archduke Franz Ferdinand was assassinated, and just five weeks later the Great Powers of Europe were at war. But how did it all happen? Historian Gordon Martel, author of The Month That Changed The World: July 1914, is blogging regularly for us over the next few weeks, giving us a week-by-week and day-by-day account of the events that led up to the First World War.

The French delegation, led by President Raymond Poincaré and the premier/foreign minister René Viviani, finally arrived in Russia. They boarded the imperial yacht, the Alexandria, while a Russian band played the ‘Marseillaise’ – that revolutionary ode to the destruction of royal and aristocratic privilege. The tsar and his foreign minister welcomed the visitors before they travelled to Peterhof where a spectacular banquet awaited them.

While the leaders of republican France and tsarist Russia were proclaiming their mutual admiration for one another, the Habsburg emperor was approving the terms of the ultimatum to be presented to Serbia three days later. No one was to be forewarned, not even their allies: Italy was to be told on Wednesday only that a note would be presented on Thursday; Germany was not to be given the details of the ultimatum until Friday – along with everyone else.

In London, Sir Edward Grey remained in the dark. He was optimistic; he told the German ambassador on Monday that a peaceful solution would be reached. It was obvious that Austria was going to make demands on Serbia, including guarantees for the future, but Grey believed that everything depended on the form of the demands, whether the Austrians would exercise moderation, and whether the accusations of Serb government complicity were convincing. If Austria kept its demands within ‘reasonable limits’ and if the necessary justification was provided, it ought to be possible to prevent a breach of the peace; ‘that any of them should be dragged into a war by Serbia would be detestable’.

On Tuesday the Germans complained that the Austrians were keeping them in the dark. From Berlin, the Austrian ambassador offered Berchtold his ‘humble opinion’ that the Germans ought to be given the details of the ultimatum immediately. After all, the Kaiser ‘and all the others in high offices’ had loyally promised their support from the first; to treat Germany in the same manner as all the other powers ‘might give offence’. Berchtold agreed to give the German ambassador a copy of the ultimatum that evening; the details should arrive at the Wilhelmstrasse by Wednesday.That same day the French visitors arrived in St Petersburg, where the mayor offered the president bread and salt – according to an old Slavic custom – and Poincaré laid a wreath on the tomb of Alexander III ‘the father’ of the Franco-Russian alliance. In the afternoon they travelled to the Winter Palace for a diplomatic levee. Along the route they were greeted by enthusiastic crowds: ‘The police had arranged it all. At every street corner a group of poor wretches cheered loudly under the eye of a policeman.’ Another spectacular banquet was held that evening, this time at the French embassy.

Perhaps the presence of the French emboldened the Russians. The foreign minister, Sergei Sazonov, warned the German ambassador that he perceived ‘powerful and dangerous influences’ might plunge Austria into war. He blamed the Austrians for the agitation in Bosnia, which arose from their misgovernment of the province. Now there were those who wanted to take advantage of the assassination to annihilate Serbia. But Russia could not look on indifferently while Serbia was humiliated, and Russia was not alone: they were now taking the situation very seriously in Paris and London.

But stern warnings in St Petersburg were not repeated elsewhere. In Vienna the French ambassador believed as late as Wednesday that Russia would not take an active part in the dispute and would try to localize it. The Russian ambassador there was so confident of a peaceful resolution that he left for his vacation that afternoon. The Russian ambassador in Berlin had already left for vacation and had yet to return; the French ambassador there returned on Thursday. The British ambassador was also absent and Grey saw no need to send him back to Berlin.

In Rome however, San Giuliano had no doubt that Austria was carefully drafting demands that could not be accepted by Serbia. He no longer believed that Franz Joseph would act as a moderating influence. The Austrian government was now determined to crush Serbia and seemed to believe that Russia would stand by and allow Serbia to ‘be violated’. Germany, he predicted, ‘would make no effort’ to restrain Austria.

By Thursday, 23 July, twenty-five days had passed since the assassination. Twenty-five days of rumours, speculations, discussions, half-truths, and hypothetical scenarios. Would the Austrian investigation into the crime prove that the instigators were directed from or supported by the government in Belgrade? Would the Serbian government assist in rooting out any individuals or organizations that may have provided assistance to the conspirators? Would Austria’s demands be limited to steps to ensure that the perpetrators would be brought to justice and such outrages be prevented from recurring in the future? Or would the assassination be utilized as a pretext for dismembering, crushing or abolishing the independence of Serbia as a state? Was Germany restraining Austria or goading it to act? Would Russia stand with Serbia in resisting Austrian demands? Would France encourage Russia to respond with restraint or push it forward? Would Italy stick with her alliance partners, stand aside, or join the other side? Could Britain promote a peaceful resolution by refusing to commit to either side in the dispute, or could it hope to counterbalance the Triple Alliance only by acting in partnership with its friends in the entente? At last, at least some of these questions were about to be answered.

At ‘the striking of the clock’ at 6 p.m. on Thursday evening the Austrian note was presented in Belgrade to the prime minister’s deputy, the chain-smoking Lazar Paču, who immediately arranged to see the Russian minister to beg for Russia’s help. Even a quick glance at the demands made in the note convinced the Serbian Crown Prince that he could not possibly accept them. The chief of the general staff and his deputy were recalled from their vacations; all divisional commanders were summoned to their posts; railway authorities were alerted that mobilization might be declared; regiments on the northern frontier were instructed to prepare assembly points for an impending mobilization. What would become the most famous diplomatic crisis in history had finally begun.

Gordon Martel is a leading authority on war, empire, and diplomacy in the modern age. His numerous publications include studies of the origins of the first and second world wars, modern imperialism, and the nature of diplomacy. A founding editor of The International History Review, he has taught at a number of Canadian universities, and has been a visiting professor or fellow in England, Ireland and Australia. Editor-in-chief of the five-volume Encyclopedia of War, he is also joint editor of the longstanding Seminar Studies in History series. His new book is The Month That Changed The World: July 1914. Read his previous blog posts.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only history articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Image credit: Raymond Poincaré, public domain via Wikimedia Commons

The post The month that changed the world: Monday, 20 July to Thursday, 23 July 1914 appeared first on OUPblog.

July 1914 was the month that changed the world. On 28 June 1914, Archduke Franz Ferdinand was assassinated, and just five weeks later the Great Powers of Europe were at war. But how did it all happen? Historian Gordon Martel, author of The Month That Changed The World: July 1914, is blogging regularly for us over the next few weeks, giving us a week-by-week and day-by-day account of the events that led up to the First World War.

Two weeks after the assassination, by Monday, 13 July, Austria’s hopes of pinning the guilt directly on the Serbian government had evaporated. The judge sent to investigate reported that he had been unable to discover any evidence proving its complicity in the plot. Perhaps the Russian foreign minister was right to dismiss the assassination as having been perpetrated by immature young men acting on their own. Any public relations initiative undertaken by Austria to justify making harsh demands on Serbia would have to rely on its failure to live up to the promises it had made five years ago to exist on good terms with Austria-Hungary.

Few anticipated an international crisis. Entente diplomats remained convinced that Germany would restrain Austria, while the British ambassador in Vienna still regarded Berchtold as ‘peacefully inclined’ and believed that it would be difficult to persuade the emperor to sanction an ‘aggressive course of action’. Triple Alliance diplomats found it difficult to envision a robust response from the Entente powers to any Austrian initiative: the cities of western Russia were plagued by devastating strikes; the possibility of civil war in Ulster loomed as a result of the British government’s home rule bill; the French public was already absorbed by the upcoming murder trial of the wife of a cabinet minister.

Austria and Germany tried to maintain an aura of calm. The chief of the Austrian general staff left for his annual vacation on Monday; the minister of war joined him on Wednesday. The chief of the German general staff continued to take the waters at a spa, while the Kaiser was encouraged not to interrupt his Baltic cruise. But behind the scenes they were resolved to act. On Tuesday Tisza assured the German ambassador that he was now ‘firmly convinced’ of the necessity of war: Austria must seize the opportunity to demonstrate its vitality; together with Germany they would now ‘look the future calmly and firmly in the face’. Berchtold explained to Berlin that the presentation of the ultimatum would be have to be delayed: the president and the premier of France would be visiting Russia on the 20-23 of July, and it was not desirable to have them there, in direct contact with the Russian government, when the demands were made. But Berchtold wanted to assure Germany that this did not indicate any ‘hesitation or uncertainty’ in Vienna. The German chancellor was unwavering in his support: he was determined to stand by Austria even if it meant taking ‘a leap into the dark’.

One of the few discordant voices was heard from London, where Prince Lichnowsky was becoming more assertive: he tried to warn Berlin of the consequences of supporting an aggressive Austrian initiative. British opinion had long supported the principle of nationality and their sympathies would ‘turn instantly and impulsively to the Serbs’ if the Austrians resorted to violence. This was not what Berlin wished to hear. Jagow replied that this might be the last opportunity for Austria to deal a death-blow to the ‘menace of a Greater Serbia’. If Austria failed to seize the opportunity its prestige ‘will be finished’, and its status was of vital interest to Germany. He prompted a German businessman to undertake a private mission to London to go around the back of his ambassador.The German chancellor remained hopeful. Bethmann Hollweg believed that Britain and France could be used to restrain Russia from intervening on Serbia’s behalf. But the support of Italy was questionable. In Rome, the Italian foreign minister argued that the Serbian government could not be held responsible for the actions of men who were not even its subjects. Italy could not offer assistance if Austria attempted to suppress the Serbian national struggle by the use of violence – or at least not unless sufficient ‘compensation’ was promised in advance.

From London Lichnowsky continued to insist that a war would neither solve Austria’s Slav problem nor extinguish the Greater Serb movement. There was no hope of detaching Britain from the Entente and Germany faced no imminent danger from Russia. Germany, he complained, was risking everything for ‘mere adventure’.

These warnings fell on deaf ears: instead of reconsidering Germany’s options the chancellor lost his confidence in Lichnowsky. Instead of recognising that Italy would fail to support its allies in a war, the German government pressed Vienna to offer compensation to Italy sufficient to change its mind. By Saturday, the secretary of state was explaining that this was Austria’s last chance for ‘rehabilitation’ and that if it were to fail its standing as a Great Power would disappear forever. The alternative was Russian hegemony in the Balkans – something that Germany could not permit. The greater the determination with which Austria acted, the more likely it was that Russia would remain quiet. Better to act now: in a few years Russia would be prepared to fight, and then ‘she will crush us by the number of her soldiers.’

On Sunday morning the ministers of the Austro-Hungarian common council gathered secretively at Betchtold’s private residence, arriving in unmarked cars. This time there was no controversy. After minimal discussion the terms of the ultimatum to be presented to Serbia were agreed upon. Count Hoyos recorded that the demands were such that no nation ‘that still possessed self- respect and dignity could possibly accept them’. They agreed to present the note containing them in Belgrade between 4 and 5 p.m. on Thursday, the 25th. If Serbia failed to reply positively within 48 hours Austria would begin to mobilize its armed forces.

Gordon Martel is a leading authority on war, empire, and diplomacy in the modern age. His numerous publications include studies of the origins of the first and second world wars, modern imperialism, and the nature of diplomacy. A founding editor of The International History Review, he has taught at a number of Canadian universities, and has been a visiting professor or fellow in England, Ireland and Australia. Editor-in-chief of the five-volume Encyclopedia of War, he is also joint editor of the longstanding Seminar Studies in History series. His new book is The Month That Changed The World: July 1914.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only history articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Image credit: Gottlieb von Jagow, public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

The post The month that changed the world: Monday, 13 July to Sunday, 19 July 1914 appeared first on OUPblog.

July 1914 was the month that changed the world. On 28 June 1914, Archduke Franz Ferdinand was assassinated, and just five weeks later the Great Powers of Europe were at war. But how did it all happen? Historian Gordon Martel, author of The Month That Changed The World: July 1914, is blogging regularly for us over the next few weeks, giving us a week-by-week and day-by-day account of the events that led up to the First World War.

Having assured the Austrians of his support on Sunday, the kaiser on Monday departed on his yacht, the Hohenzollern, for his annual summer cruise of the Baltic. When his chancellor, Theobald von Bethmann Hollweg, met with Count Hoyos and the Austrian ambassador in Berlin that afternoon, he confirmed that Germany would stand by them ‘shoulder-to-shoulder’. He agreed that Russia was attempting to form a ‘Balkan League’ which threatened the interests of the Triple Alliance. He promised to seize the initiative: he would begin negotiations to bring Bulgaria into the alliance and he would advise Romania to stop nationalist agitation there against Austria. He would leave it to the Austrians to decide how to proceed with Serbia, but they ‘may always be certain that Germany will remain at our side as a faithful friend and ally’.

In London the German ambassador, now back from a visit home, arranged to meet with the British foreign secretary, Sir Edward Grey, on Monday afternoon. Prince Lichnowsky aimed to persuade Grey that Germany and Britain should co-operate to ‘localize’ the dispute between Austria and Serbia. Lichnowsky explained that the feeling was growing in Germany that it was better not to restrain Austria, to ‘let the trouble come now, rather than later’ and he reported that Grey understood Austria would have to adopt ‘severe measures’.

On Tuesday the Austrian government met in Vienna to determine precisely how far and how fast they were prepared to move against Serbia. The meeting went on for most of the day. The emperor did not attend; in fact, he left the city that morning to return to his hunting lodge, five hours away, where he would remain for the next three weeks. Berchtold, in the chair, told the assembled ministers that the moment had come to decide whether to render Serbia’s intrigues harmless forever. He assured them that Germany had promised its support in the event of any ‘warlike complications’.

The ministers agreed that vigorous measures were needed. Only the Hungarian minister-president expressed any concern. Tisza insisted that they prepare the diplomatic ground before taking any military action, otherwise they would be discredited in the eyes of Europe. They should begin by presenting Serbia with a list of demands: if these were accepted they would have achieved a splendid diplomatic victory; if they were rejected, he would vote for war. Berchtold and the others disagreed: only by the exertion of force could the fundamental problem of the propaganda for a Greater Serbia emanating from Belgrade be eliminated. The argument went on for hours, but Tisza had the power of a virtual veto: Austria-Hungary could not go to war without his agreement. Reluctantly, the ministers agreed to formulate a set of demands to present to Serbia. These should be so stringent however as to make refusal ‘almost certain’.On Wednesday, 8 July, officials at the Ballhausplatz began working on the draft of an ultimatum to be presented to Serbia. They were in no hurry. The chief of the general Staff, Conrad von Hötzendorff, had determined that, with so many conscript soldiers on leave to assist in the gathering of the harvest, it would be impossible to begin mobilization before 25 July. The ultimatum could not be presented until 22-23 July.

By Thursday in Berlin they were beginning to envision a diplomatic victory for the Triple Alliance. The secretary of state, Gottlieb von Jagow, just returned from his honeymoon, told the Italian ambassador that Austria could not afford to be submissive when confronted by a Serbia ‘sustained or driven on by the provocative support of Russia’. But he did not believe that ‘a really energetic and coherent action’ on their part would lead to a conflict. From London, Prince Lichnowsky reported that Sir Edward Grey had reassured him that he had made no secret agreements with France and Russia that entailed any obligations in the event of a European war. Rather, Britain wished to preserve the ‘absolutely free hand’ that would allow it to act according to its own judgement. Grey appeared confident, cheerful and ‘not pessimistic’ about the situation in the Balkans.

Meeting with the German ambassador in Vienna on Friday, Berchtold sketched some preliminary ideas of what the ultimatum to Serbia might consist of. Perhaps they might demand that an agency of the Austro-Hungarian government be established at Belgrade to monitor the machinations of the ‘Greater Serbia’ movement; perhaps they might insist that some nationalist organizations be dissolved; perhaps they could stipulate that certain army officers be dismissed. He wanted to be sure that the demands went so far that Serbia could not possibly accept them. What did they think in Berlin?

Berlin chose not to think anything. The ambassador was instructed to inform Berchtold that Germany could take no part in formulating the demands. Instead, he was advised to collect evidence that would show the Greater Serbia agitation in Belgrade threatened Austria’s existence.

At the same time the fourth – but secret – member of the Triple Alliance, Romania, was warning that it would not be able to meet its obligations to assist Austria. Romanians, the Hohenzollern king advised, were offended by Hungary’s treatment of its Romanian population: they now regarded Austria, not Russia, as their primary enemy. King Karl did not believe the Serbian government was involved in the assassination and complained that the Austrians seemed to have lost their heads. Berlin should exert its influence on Vienna to extinguish the ‘pusillanimous spirit’ there.

By the end of the week Italy had added its voice to the chorus of restraint. The foreign minister, the Marchese di San Giuliano, insisted that governments of democratic countries (such as Serbia) ‘could not be held accountable for the transgressions of the press’. The Austrians should not be unfair, and he was urging moderation on the Serbians. There seemed every reason to believe that peace would endure: the British ambassador in Vienna thought the government would hesitate to take a step that would produce ‘great international tension’, and the Serbian minister there had assured him that he had no reason to expect a ‘threatening communication’ from Austria.

Gordon Martel is a leading authority on war, empire, and diplomacy in the modern age. His numerous publications include studies of the origins of the first and second world wars, modern imperialism, and the nature of diplomacy. A founding editor of The International History Review, he has taught at a number of Canadian universities, and has been a visiting professor or fellow in England, Ireland and Australia. Editor-in-chief of the five-volume Encyclopedia of War, he is also joint editor of the longstanding Seminar Studies in History series. His new book is The Month That Changed The World: July 1914.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only history articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Image credit: Map highlighting the Triple Alliance. By Nydas. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons

The post The month that changed the world: Monday, 6 July to Sunday, 12 July 1914 appeared first on OUPblog.

July 1914 was the month that changed the world. On 28 June 1914, Archduke Franz Ferdinand was assassinated, and just five weeks later the Great Powers of Europe were at war. But how did it all happen? Historian Gordon Martel, author of The Month That Changed The World: July 1914, is blogging regularly for us over the next few weeks, giving us a week-by-week and day-by-day account of the events that led up to the First World War.

Although it was Sunday, news of the assassination rocketed around the capitals of Europe. By evening Princip and Čabrinović had been arrested, charged, taken to the military prison and put in chains. All of Čabrinović’s family had been rounded up and arrested, along with those they employed in the family café; Ilić was arrested that afternoon. The remaining conspirators fled the city but within days six of the seven had been captured.

On Sunday evening crowds of young Croatian and Muslim men gathered and marched through Sarajevo, singing the Bosnian anthem and shouting ‘Down with the Serbs’. About one hundred of them stoned the Hotel Europa, owned by a prominent Serb and frequented by Serbian intellectuals. The next morning Croat and Muslim leaders held a rally to demonstrate their support for Austrian rule. They sang the national anthem of the monarchy and carried portraits of the emperor. Sporadic demonstrations quickly escalated into full-scale rioting. Crowds began smashing windows of Serbian businesses and institutions, ransacking the Serbian school, stoning the residence of the head of the Serbian Orthodox Church in Sarajevo and besieging the homes of prominent Serbs.

The people of Vienna had remained calm when news of the assassination arrived on Sunday, but by Monday afternoon a crowd gathered at the Serbian legation and police had to be called in. Behind the scenes the chief of Austria-Hungary’s general staff argued that they must ‘draw the sword’ against Serbia. Leading Viennese newspapers however argued against a campaign of revenge. The emperor returned to Vienna from his hunting lodge on Monday, blaming himself for the killings: God was punishing him for permitting Franz Ferdinand’s marriage to Sophie.

By Tuesday the Austro-Hungarian foreign minister, Count Berchtold, was convinced that the conspiracy had been planned in Belgrade. But what would he propose to do? Would he agree to ‘draw the sword’ against Serbia? Or might he be satisfied with Serbian promises to act against those involved in the conspiracy? His choice would rest largely upon the advice he received from his German allies: he could not risk war without German support.

The German ambassador in Vienna preached restraint. Meeting with Berchtold on Tuesday, Heinrich von Tschirschky advised him not to act in haste, to first decide exactly what he wished to achieve and to weigh his options carefully. Neither of their other allies – Italy and Romania – were likely to support an energetic response. In Berlin, a leading official at the Wilhelmstrasse (the German foreign office), confided to the Italian ambassador his fear that the Austrians might adopt ‘severe and provocative’ measures and that Germany would be faced with the task of restraining them.On Wednesday Serbia’s prime minister instructed his representatives to explain that his government had taken steps to suppress anarchic elements within Serbia, and that it would now redouble its vigilance and take the severest measures against them: ‘Serbia will do everything in her power and use all the means at her disposal in order to restrain the feelings of ill-balanced people within her frontiers.’

Might this satisfy the Austrians? Ambassador Tschirschky could not envision them demanding more than that Serbia should cooperate in an investigation into the assassination. At the same time, the Hungarian minister-president, István Tisza, was urging the emperor not to use the assassination as an excuse for a ‘reckoning’ with Serbia: it could be fatal to proceed without proof that the Serbian government had been complicit in the plot.

Few expected Count Berchtold to act decisively. He was widely regarded as intelligent but weak, charming but cautious. No one expected him to undertake anything adventurous, and he now appeared to fulfil these expectations. Before making any crucial decisions Berchtold revised an existing memorandum that advised how to meet the growing threat of Russia in the Balkans and turned it into a plea for German support in Austria’s coercion of Serbia. He then drafted a ‘personal’ letter to be sent from the emperor to the kaiser. On Thursday Franz Joseph wrote the letter in his own hand: the crime committed against his nephew (no mention of the duchess) had resulted directly from the agitation conducted by ‘Russian and Serbian Panslavists’ who were determined to weaken the Triple Alliance and ‘shatter my empire’. The Serbian government aimed to unite all south-Slavs under the Serbian flag, which was a lasting danger ‘to my house and to my countries’.

By Thursday a preliminary police investigation had identified seven principal conspirators. Six of them had been taken into custody. Interrogations of the prisoners already indicated that they could be linked to highly-placed officials in Belgrade. And the Austrian military attaché in Belgrade was sending reports linking the conspiracy to Serbian army officers and to the Narodna Odbrana. The pieces of the puzzle seemed to be fitting into place. That evening the bodies of the archduke and the duchess arrived in Vienna; they were to lie in state at the Hofburg Palace until a requiem mass was said on Saturday. They would then be transported to their final resting-place in the chapel Franz Ferdinand had built for that purpose at his castle in Artstetten.

The politicians and diplomats of the so-called Triple Entente – France, Russia, and Britain – expressed few fears of an impending international crisis in the week following the assassination. When the French cabinet met following the assassination on Tuesday the situation arising from Sarajevo was barely mentioned. The French ambassador in Vienna believed the emperor would restrain those seeking revenge and that Austria was not likely to go beyond making threats. The Russian ambassador agreed: he did not believe that the Austrian government would allow itself to be rushed into a war for which it was not prepared. In London, the permanent under-secretary of state at the Foreign Office doubted that Austria would undertake any ‘serious’ action.

While Entente diplomats were comforting themselves with the thought that Austria would not go beyond words, Berchtold despatched his chef de cabinet, Count Hoyos, to Berlin. He carried with him the emperor’s letter to the kaiser and the long memorandum on the Balkan situation that the foreign minister had revised for the purpose. Hoyos, one of the ‘young rebels’ at the Ballhausplatz (the Austrian foreign office), advocated an aggressive foreign policy as an antidote to the monarchy’s apparent decline. Before leaving for Berlin he told a German journalist that he believed Austria must seize the opportunity to ‘solve’ the Serbian problem. It would be most valuable if Germany promised to ‘cover our rear’.

In Berlin on Sunday 5 July 1914 the Germans seemed prepared to do just that. Although the Kaiser expressed his concern that severe measures against Serbia might lead to serious complications he promised that Austria could rely upon the full support of Germany. He did not believe that the Russians were prepared for war, but even if it came to this he assured the Austrian ambassador that Germany would ‘stand at our side’ and that it would be regrettable if Austria failed to seize the moment ‘which is so favourable to us.’ This would go down in legend as the ‘blank cheque’.

Gordon Martel is a leading authority on war, empire, and diplomacy in the modern age. His numerous publications include studies of the origins of the first and second world wars, modern imperialism, and the nature of diplomacy. A founding editor of The International History Review, he has taught at a number of Canadian universities, and has been a visiting professor or fellow in England, Ireland and Australia. Editor-in-chief of the five-volume Encyclopedia of War, he is also joint editor of the longstanding Seminar Studies in History series. His new book is The Month That Changed The World: July 1914.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only history articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Image credit: Count Leopold Berchtold. By Philip de László. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons

The post The month that changed the world: Monday, 29 June to Sunday, 5 July 1914 appeared first on OUPblog.

July 1914 was the month that changed the world. On 28 June 1914, Archduke Franz Ferdinand was assassinated, and just five weeks later the Great Powers of Europe were at war. But how did it all happen? Historian Gordon Martel, author of The Month That Changed The World: July 1914, is blogging regularly for us over the next few weeks, giving us a week-by-week and day-by-day account of the events that led up to the First World War.

At 10 a.m. that morning the royal party arrived at the railway station. A motorcade consisting of six automobiles was to proceed from there along the Appel Quay to the city hall.The first automobile was to be manned by four special security detectives assigned to guard the archduke, but only one of them managed to take his place; local policemen substituted for the others. The next car was to carry the mayor, Fehim Effendi Čurćić, wearing his red fez, and the chief of police, Dr Edmund Gerde – who had warned the military authorities about the dangerous atmosphere in Sarajevo and had advised against proceeding with the visit.

The archduke and the duchess were seated next to one another in the third car, facing General Potiorek (the military governor of Bosnia) and the owner of the limousine, Count Harrach. The archduke and duchess conducted a brief inspection of the military barracks before setting out for the city hall, where they were to be formally welcomed before proceeding to open the new state museum, designed to display the benefits of Austrian rule.

Seven would-be assassins mingled with the gathering crowds for over an hour before the motorcade arrived. Ilić had assigned one of them, Nedeljko Čabrinović, a place across the street from two others stationed in front of the garden at the Mostar Café, situated near the first bridge on the route, the Čumurja. Ilić and another assassin took their places on the other side of the street; Gavrilo Princip was placed 200 yards further along the route, at the Lateiner bridge. All seven were in place when the royal party arrived at the station that morning.

Ten minutes before the motorcade reached the Čumurja bridge a policeman approached Čabrinović, demanding that he identify himself. He produced a permit that purported to have been issued by the Viennese police and asked the policeman which car was carrying the archduke. ‘The third’ he was told. A few minutes later he took out his grenade, knocked off the detonator cap and threw it at the limousine carrying the archduke and the duchess. Because there was a twelve-second delay between knocking off the cap and the explosion, the grenade hit the limousine, bounced off, rolled under the next car, and exploded. General Potiorek’s aide-de-camp was injured, along with several spectators. The duchess suffered a slight wound to her cheek, where she had been grazed by the grenade’s detonator.Čabrinović swallowed his cyanide capsule and jumped over the embankment into the river. But the cyanide failed and the river had been reduced to a mere trickle in mid-summer. He was captured immediately by a policeman who asked him if he was a Serb. ‘Yes, I am a Serb hero’, he replied.

The procession continued on its way to the splendid new city hall, the neo-Moorish Vijećnica, meant to evoke the Alhambra as part of Austria’s ‘neo-Orientalist’ policy designed to cultivate the support of Bosnia’s Muslims. When the royal party arrived, the mayor began to read the effusive speech he had prepared in their honour – apparently unaware of the near calamity that had just occurred. The archduke interrupted, angrily demanding to know how the mayor could speak of ‘loyalty’ to the crown when a bomb had just been thrown at him. The duchess, playing her accustomed role, managed to calm him down while they waited for a staff officer to arrive with a copy of the archduke’s speech – which was now splattered in blood.

After the speeches and a reception General Potiorek proposed that they either drive back along the Appel Quay at full speed to the station or go straight to his residence, only a few hundred metres away, and where lunch awaited them. But the archduke insisted on first visiting the wounded officer at the military hospital. The duchess insisted on accompanying him: ‘It is in time of danger that you need me.’

The royal couple, along with Potiorek, climbed into a new car, with Count Harrach standing on the footboard to shield the archduke from any other would-be assassins. A first car, with the chief of police and others, was to precede them. In order to reach the hospital the motorcade was forced to retrace its route along the Appel Quay. Princip, who had almost abandoned hopeafter Čabrinović’s arrest, was still waiting near the Lateiner bridge when the two cars unexpectedly appeared in front of him.

The driver of the first car had turned right off the Appel Quay, following the original route to take them to the museum; the driver of the second car followed him. General Potiorek, immediately recognizing the mistake, ordered his driver to stop. The car then began to reverse slowly in order to get back onto the Appel Quay – with Count Harrach now on the opposite side of the car to Princip, who was standing at the corner of Appel Quay and Franz Joseph Street, in front of Schiller’s delicatessen. Seizing the opportunity, Princip stepped out of the crowd. His moment had arrived.

Because it was too difficult to take the grenade out of his coat and knock off the detonator cap, Princip decided to use his revolver instead. A policeman spotted him and tried to intervene, but a friend of Princip’s kicked the policeman in the knee and knocked him off balance. The first shot hit the archduke near the jugular vein; the second hit the duchess in the stomach. ‘Soferl, Soferl!’ Franz Ferdinand cried, ‘Don’t die. Live for our children.’ The duchess was already dead by the time they reached the governor’s residence. The archduke, unconscious when he was carried inside, was also dead within minutes – before either a doctor or a priest could be summoned.

Spectators were attempting to lynch Princip when the police rescued him. He tried to swallow the cyanide capsule, but vomited it up. An Austrian judge, interviewing him almost immediately afterwards, wrote: ‘The young assassin, exhausted by his beating, was unable to utter a word. He was undersized, emaciated, sallow, sharp featured. It was difficult to imagine that so frail looking an individual could have committed so serious a deed.’

Gordon Martel is a leading authority on war, empire, and diplomacy in the modern age. His numerous publications include studies of the origins of the first and second world wars, modern imperialism, and the nature of diplomacy. A founding editor of The International History Review, he has taught at a number of Canadian universities, and has been a visiting professor or fellow in England, Ireland and Australia. Editor-in-chief of the five-volume Encyclopedia of War, he is also joint editor of the longstanding Seminar Studies in History series. His new book is The Month That Changed The World: July 1914.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only history articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Image credit: Princip arrest [public domain]. Via Wikimedia Commons.

The post The month that changed the world: Sunday, 28 June 1914 appeared first on OUPblog.

July 1914 was the month that changed the world. On 28 June 1914, Archduke Franz Ferdinand was assassinated, and just five weeks later the Great Powers of Europe were at war. But how did it all happen? Historian Gordon Martel, author of The Month That Changed The World: July 1914, will be blogging regularly for us over the next few weeks, giving us a week-by-week and day-by-day account of the events that led up to the First World War. His first post focuses on the events of Saturday, 27 June 1914.

The next day was to be a brilliant one, a splendid occasion that would glorify the achievements of Austrian rule in Bosnia-Herzegovina. The Habsburg heir to the thrones of Austria and Hungary, the Archduke Franz Ferdinand, had been eagerly anticipating it for months. He envisioned making a triumphal entry into the city of Sarajevo, attired in his uniform as inspector-general of the Austro-Hungarian army, and accompanied by his wife, the duchess. Sophie would be resplendent in a full-length white dress with red sash tied at the waist, she would hold a parasol to shelter from the sun and a fan to cool her; gloves, furs and a magnificent hat would complete the outfit.

The date of Sunday, 28 June had been chosen carefully: it was the anniversary of the battle of Kosovo in 1389, at which the medieval Serbian kingdom had been extinguished by the victorious Turks. Afterwards, Bosnia and Herzegovina remained provinces of the Ottoman empire for almost 500 years, until occupied by Austro-Hungarian forces in 1878 and then annexed in 1908. Thus, on the occasion of the archduke’s visit, the Serbs of Bosnia were asked to pay homage to a member of the royal family that blocked the way to uniting all Serbs in a Greater Serbia. The location was also provocative: the archducal visit to Sarajevo was preceded by military manoeuvres in the mountains south of the city – not far from the frontier with Serbia.

The Austrians disregarded warnings of trouble. The Serbian minister in Vienna had suggested to the minister responsible for Bosnian affairs that some Serbs might regard the time and place of the visit as a deliberate affront. Perhaps, he warned, some young Serb participating in the Austrian manoeuvres might substitute live ammunition for blanks – and seize the opportunity to fire at the archduke. Politicians and officials on the spot in Sarajevo had advised that the visit be cancelled; the police warned that they could not guarantee the archduke’s safety, particularly given the lengthy route that that the royal couple were scheduled to take along the Miljačka river from the railway station to the city hall.