new posts in all blogs

Viewing: Blog Posts Tagged with: martel, Most Recent at Top [Help]

Results 1 - 5 of 5

How to use this Page

You are viewing the most recent posts tagged with the words: martel in the JacketFlap blog reader. What is a tag? Think of a tag as a keyword or category label. Tags can both help you find posts on JacketFlap.com as well as provide an easy way for you to "remember" and classify posts for later recall. Try adding a tag yourself by clicking "Add a tag" below a post's header. Scroll down through the list of Recent Posts in the left column and click on a post title that sounds interesting. You can view all posts from a specific blog by clicking the Blog name in the right column, or you can click a 'More Posts from this Blog' link in any individual post.

By: PennyF,

on 8/5/2014

Blog:

OUPblog

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

Books,

History,

World,

world war I,

map,

month,

diplomacy,

gordon,

july,

first world war,

1914,

*Featured,

Images & Slideshows,

changed,

Archduke Franz Ferdinand,

gordon martel,

july 1914,

the month that changed the world,

martel,

Gottlieb von Jagow,

Sir Edward Grey,

Raymond Poincaré,

Tsar Nicholas II,

Herbert Asquith,

Kaiser Wilhelm II,

King George V,

contributed,

Add a tag

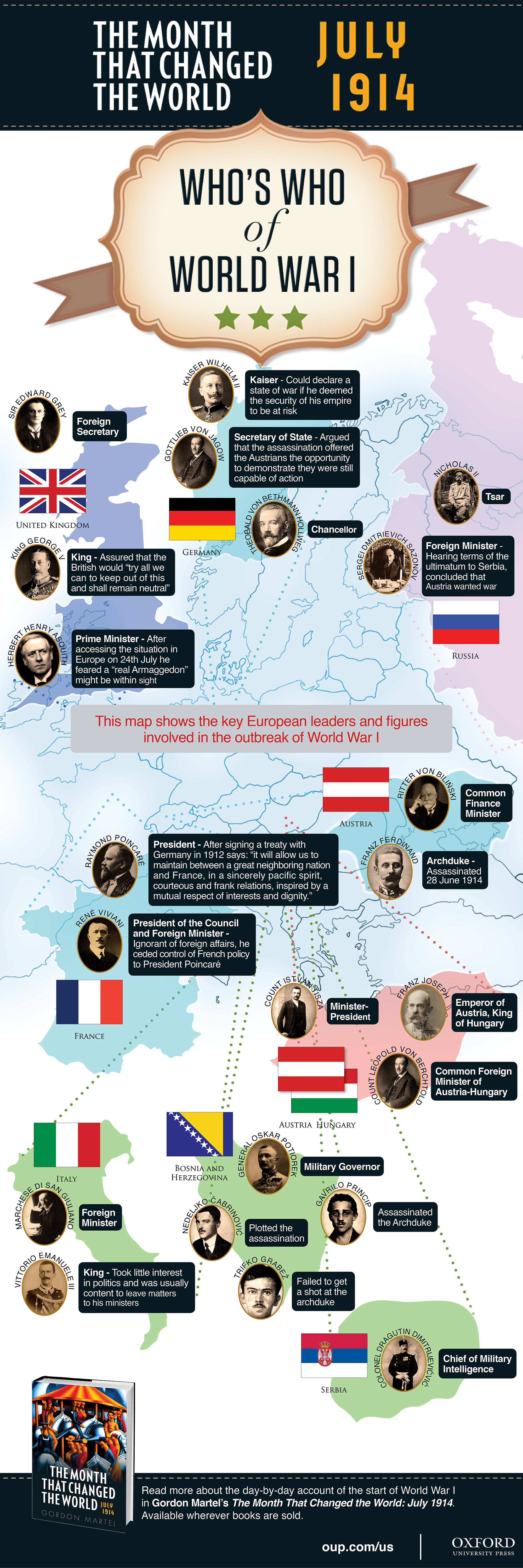

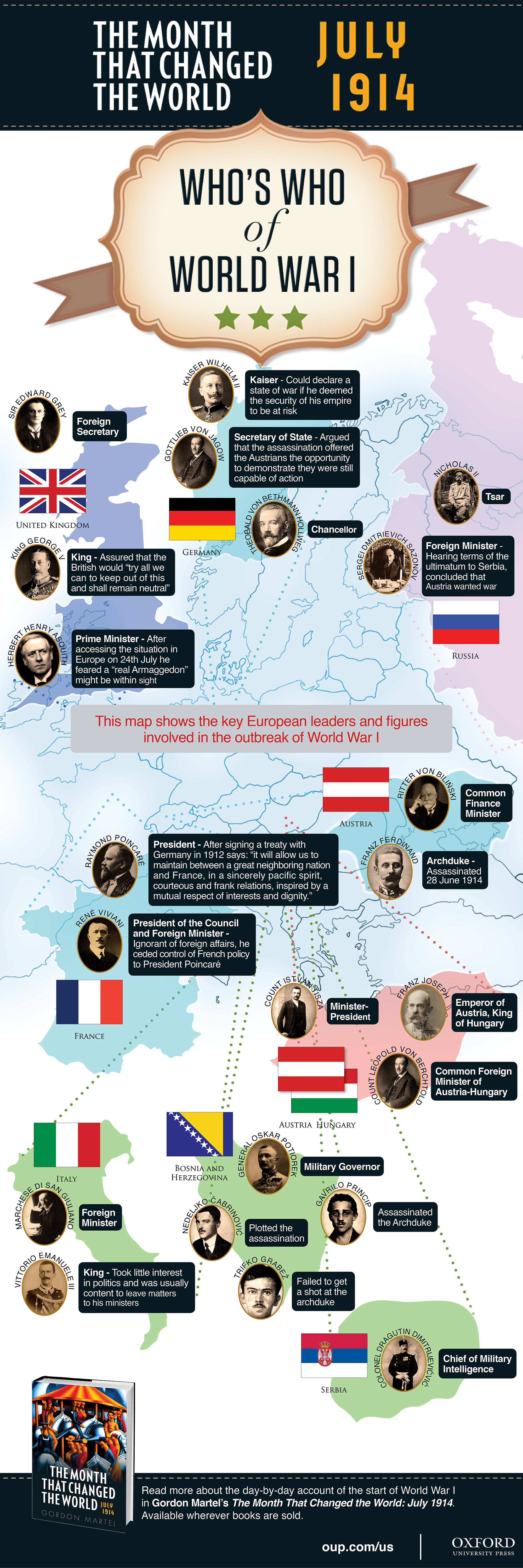

Over the last few weeks, historian Gordon Martel, author of The Month That Changed The World: July 1914, has been blogging regularly for us, giving a week-by-week and day-by-day account of the events leading up to the First World War. July 1914 was the month that changed the world, but who were the people that contributed to that change? We wrap up the series with a Who’s Who of World War I below. Key countries have been highlighted with the corresponding figures and leaders that contributed to the outbreak of war.

Download a jpeg or PDF of the map.

Gordon Martel is a leading authority on war, empire, and diplomacy in the modern age. His numerous publications include studies of the origins of the first and second world wars, modern imperialism, and the nature of diplomacy. A founding editor of The International History Review, he has taught at a number of Canadian universities, and has been a visiting professor or fellow in England, Ireland and Australia. Editor-in-chief of the five-volume Encyclopedia of War, he is also joint editor of the longstanding Seminar Studies in History series. His new book is The Month That Changed The World: July 1914.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only history articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

The post Political map of Who’s Who in World War I [infographic] appeared first on OUPblog.

By: Kirsty,

on 7/26/2014

Blog:

OUPblog

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

Books,

History,

war,

military history,

World,

British,

This Day in History,

Europe,

wwi,

World War One,

first world war,

*Featured,

kaiser,

UKpophistory,

gordon martel,

july 1914,

the month that changed the world,

martel,

the july crisis,

WWI centenary,

Add a tag

July 1914 was the month that changed the world. On 28 June 1914, Archduke Franz Ferdinand was assassinated, and just five weeks later the Great Powers of Europe were at war. But how did it all happen? Historian Gordon Martel, author of The Month That Changed The World: July 1914, is blogging regularly for us over the next few weeks, giving us a week-by-week and day-by-day account of the events that led up to the First World War.

By Gordon Martel

When day dawned on Sunday, 26 July, the sky did not fall. Shells did not rain down on Belgrade. There was no Austrian declaration of war. The morning remained peaceful, if not calm. Most Europeans attended their churches and prepared to enjoy their day of rest. Few said prayers for peace; few believed divine intervention was necessary. Europe had weathered many storms over the last decade. Only pessimists doubted that this one could be weathered as well.

In Austria-Hungary the right of assembly, the secrecy of the mail, of telegrams and telephone conversations, and the freedom of the press were all suspended. Pro-war demonstrations were not only permitted but encouraged: demonstrators filled the Ringstrasse, marched on the Ballhausplatz, gathered around statues of national heroes and sang patriotic songs. That evening the Bürgermeister of Vienna told a cheering crowd that the fate of Europe for centuries to come was about to be decided, praising them as worthy descendants of the men who had fought Napoleon. The Catholic People’s Party newspaper, Alkotmány, declared that ‘History has put the master’s cane in the Monarchy’s hands. We must teach Serbia, we must make justice, we must punish her for her crimes.’

Kaiser Wilhelm

Just how urgent was the situation? In London, Sir Edward Grey had left town on Saturday afternoon to go to his cottage for a day of fly-fishing on Sunday. The Russian ambassadors to Germany, Austria and Paris had yet to return to their posts. The British ambassadors to Germany and Paris were still on vacation. Kaiser Wilhelm was on his annual yachting cruise of the Baltic. Emperor Franz Joseph was at his hunting lodge at Bad Ischl. The French premier and president were visiting Stockholm. The Italian foreign minister was still taking his cure at Fiuggi. The chiefs of the German and Austrian general staffs remained on leave; the chief of the Serbian general staff was relaxing at an Austrian spa.

Could calm be maintained? Contradictory evidence seemed to be coming out of St Petersburg. It seemed that some military steps were being initiated – but what these were to be remained uncertain. Sazonov, the Russian foreign minister, met with both the German and Austrian ambassadors on Sunday – and both noted a significant change in his demeanour. He was now ‘much quieter and more conciliatory’. He emphatically insisted that Russia did not desire war and promised to exhaust every means to avoid it. War could be avoided if Austria’s demands stopped short of violating Serbian sovereignty. The German ambassador suggested that Russia and Austria discuss directly a softening of the demands. Sazonov, who agreed immediately to suggest this, was ‘now looking for a way out’. The Germans were assured that only preparatory measures had been undertaken thus far – ‘not a horse and not a reserve had been called to service’.

By late Sunday afternoon, the situation seemed precarious but not hopeless. The German chancellor worried that any preparatory measures adopted by Russia that appeared to be aimed at Germany would force the adoption of counter-measures. This would mean the mobilization of the German army – and mobilization ‘would mean war’. But he continued to hope that the crisis could be ‘localized’ and indicated that he would encourage Vienna to accept Grey’s proposed mediation and/or direct negotiations between Austria and Russia.

By Sunday evening more than 24 hours had passed since the Austrian legation had departed from Belgrade and Austria had severed diplomatic relations with Serbia. Many had assumed that war would follow immediately, but there had been no invasion of Serbia or even a declaration of war. The Austrians, in spite of their apparent firmness in refusing any alteration of the terms or any extension of the deadline, appeared not to know what step to take next, or when additional steps should be taken. When asked, the Austrian chief of staff suggested that any declaration of war ought to be postponed until 12 August. Was Europe really going to hold its breath for two more weeks?

Gordon Martel is a leading authority on war, empire, and diplomacy in the modern age. His numerous publications include studies of the origins of the first and second world wars, modern imperialism, and the nature of diplomacy. A founding editor of The International History Review, he has taught at a number of Canadian universities, and has been a visiting professor or fellow in England, Ireland and Australia. Editor-in-chief of the five-volume Encyclopedia of War, he is also joint editor of the longstanding Seminar Studies in History series. His new book is The Month That Changed The World: July 1914. Read his previous blog posts.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only history articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Image credit: Kaiser Wilhelm, public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

The post The month that changed the world: Sunday, 26 July 1914 appeared first on OUPblog.

By: Kirsty,

on 7/25/2014

Blog:

OUPblog

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

*Featured,

UKpophistory,

gordon martel,

july 1914,

the month that changed the world,

martel,

the july crisis,

WWI centenary,

ischl,

kaiservilla,

tornadoo,

kaiserville,

Books,

History,

military history,

World,

world war I,

austria,

British,

This Day in History,

Europe,

wwi,

first world war,

serbia,

Add a tag

July 1914 was the month that changed the world. On 28 June 1914, Archduke Franz Ferdinand was assassinated, and just five weeks later the Great Powers of Europe were at war. But how did it all happen? Historian Gordon Martel, author of The Month That Changed The World: July 1914, is blogging regularly for us over the next few weeks, giving us a week-by-week and day-by-day account of the events that led up to the First World War.

By Gordon Martel

Would there be war by the end of the day? It certainly seemed possible: the Serbs had only until 6 p.m. to accept the Austrian demands. Berchtold had instructed the Austrian representative in Belgrade that nothing less than full acceptance of all ten points contained in the ultimatum would be regarded as satisfactory. And no one expected the Serbs to comply with the demands in their entirety – least of all the Austrians.

When the Serbian cabinet met that morning they had received advice from Russia, France, and Britain urging them to be as accommodating as possible. No one indicated that any military assistance might be forthcoming. They began drafting a ‘most conciliatory’ reply to Austria while preparing for war: the royal family prepared to leave Belgrade; the military garrison left the city for a fortified town 60 miles south; the order for general mobilization was signed and drums were beaten outside of cafés, calling up conscripts.

Kaiservilla in Bad Ischl, Austria: the summer residence of Emperor Franz Joseph I. Kaiserville, Bad Ischl, Austria. By Blue tornadoo CC-BY-SA-3.0, via Wikimedia Commons

How would Russia respond? That morning the tsar presided over a meeting of the Russian Grand Council where it was agreed to mobilize the thirteen army corps designated to act against Austria. By afternoon ‘the period preparatory to war’ was initiated and preparations for mobilization began in the military districts of Kiev, Odessa, Moscow, and Kazan.

Simultaneously, Sazonov tried to enlist German support in persuading Austria to extend the deadline beyond 6 p.m., arguing that it was a ‘European matter’ not limited to Austria and Serbia. The Germans refused, arguing that to summon Austria to a European ‘tribunal’ would be humiliating and mean the end of Austria as a Great Power. Sazonov insisted that the Austrians were aiming to establish hegemony in the Balkans: after they devoured Serbia and Bulgaria Russia would face them ‘on the Black Sea’. He tried to persuade Sir Edward Grey that if Britain were to join Russia and France, Germany would then pressure Austria into moderation.

How would Britain respond? Sir Edward Grey gave no indication that Britain would stand shoulder-to-shoulder with the Russians in a conflict over Serbia. His only concern seemed to be to contain the crisis, to keep it a dispute between Austria and Serbia. ‘I do not consider that public opinion here would or ought to sanction our going to war over a Servian quarrel’. But if a war between Austria and Serbia were to occur ‘other issues’ might draw Britain in. In the meantime, there was still an opportunity to avert war if the four disinterested powers ‘held the hand’ of their partners while mediating the dispute. But the report he received from St Petersburg was not encouraging: the British ambassador warned that Russia and France seemed determined to make ‘a strong stand’ even if Britain declined to join them.

When the Austrian minister received the Serb reply at 5:58 on Saturday afternoon, he could see instantly that their submission was not complete. He announced that Austria was breaking off diplomatic relations with Serbia and immediately ordered the staff of the delegation to leave for the railway station. By 6:30 the Austrians were on a train bound for the border.

That evening, in the Kaiservilla at Bad Ischl, Franz Joseph signed the orders for mobilization of thirteen army corps. When the news reached Vienna the people greeted it with the ‘wildest enthusiasm’. Huge crowds began to form, gathering at the Ringstrasse and bursting into patriotic songs. The crowds marched around the city shouting ‘Down with Serbia! Down with Russia’. In front of the German embassy they sang ‘Wacht am Rhein’; police had to protect the Russian embassy against the demonstrators. Surely, it would not be long before the guns began firing.

Gordon Martel is a leading authority on war, empire, and diplomacy in the modern age. His numerous publications include studies of the origins of the first and second world wars, modern imperialism, and the nature of diplomacy. A founding editor of The International History Review, he has taught at a number of Canadian universities, and has been a visiting professor or fellow in England, Ireland and Australia. Editor-in-chief of the five-volume Encyclopedia of War, he is also joint editor of the longstanding Seminar Studies in History series. His new book is The Month That Changed The World: July 1914.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only history articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

The post The month that changed the world: Saturday, 25 July 1914 appeared first on OUPblog.

By: Kirsty,

on 7/24/2014

Blog:

OUPblog

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

Books,

History,

military history,

World,

austria,

British,

This Day in History,

Europe,

wwi,

World War One,

first world war,

hungary,

Serbia,

*Featured,

serbian,

UKpophistory,

gordon martel,

july 1914,

the month that changed the world,

martel,

july crisis,

Berchtold,

Edward Grey,

Austria-Hungary,

Austrian ultimatum,

Sazonov,

sergey,

Add a tag

July 1914 was the month that changed the world. On 28 June 1914, Archduke Franz Ferdinand was assassinated, and just five weeks later the Great Powers of Europe were at war. But how did it all happen? Historian Gordon Martel, author of The Month That Changed The World: July 1914, is blogging regularly for us over the next few weeks, giving us a week-by-week and day-by-day account of the events that led up to the First World War.

By Gordon Martel

By mid-day Friday heads of state, heads of government, foreign ministers, and ambassadors learned the terms of the Austrian ultimatum. A preamble to the demands asserted that a ‘subversive movement’ to ‘disjoin’ parts of Austria-Hungary had grown ‘under the eyes’ of the Serbian government. This had led to terrorism, murder, and attempted murder. Austria’s investigation of the assassination of the archduke revealed that Serbian military officers and government officials were implicated in the crime.

A list of ten demands followed, the most important of which were: Serbia was to suppress all forms of propaganda aimed at Austria-Hungary; the Narodna odbrana was to be dissolved, along with all other subversive societies; officers and officials who had participated in propaganda were to be dismissed; Austrian officials were to participate in suppressing the subversive movements in Serbia and in a judicial inquiry into the assassination.

When Sazonov saw the terms he concluded that Austria wanted war: ‘You are setting fire to Europe!’ If Serbia were to comply with the demands it would mean the end of its sovereignty. ‘What you want is war, and you have burnt your bridges behind you’. He advised the tsar that Serbia could not possibly comply, that Austria knew this and would not have presented the ultimatum without the promise of Germany’s support. He told the British and French ambassadors that war was imminent unless they acted together.

But would they? With the French president and premier now at sea in the Baltic, and with wireless telegraphy problematic, foreign policy was in the hands of Bienvenu-Martin, the inexperienced minister of justice. He believed that Austria was within its rights to demand the punishment of those implicated in the crime and he shared Germany’s wish to localize the dispute. Serbia could not be expected to agree to demands that impinged upon its sovereignty, but perhaps it could agree to punish those involved in the assassination and to suppress propaganda aimed at Austria-Hungary.

Sir Edward Grey was shocked by the extent of the demands. He had never before seen ‘one State address to another independent State a document of so formidable a character.’ The demand that Austria-Hungary be given the right to appoint officials who would have authority within the frontiers of Serbia could not be consistent with Serbia’s sovereignty. But the British government had no interest in the merits of the dispute between Austria and Serbia; its only concern was the peace of Europe. He proposed that the four ‘disinterested powers’ (Britain, Germany, France and Italy) act together at Vienna and St Petersburg to resolve the dispute. After Grey briefed the cabinet that afternoon, the prime minister concluded that although a ‘real Armaggedon’ was within sight, ‘there seems…no reason why we should be more than spectators’.

Nothing that the Austrians or the Germans heard in London or Paris on Friday caused them to reconsider their course. In fact, their general impression was that the Entente Powers wished to localize the dispute. Even from St Petersburg the German ambassador reported that Sazonov’s reference to Austria’s ‘devouring’ of Serbia meant that Russia would take up arms only if Austria seized Serbian territory and that his wish to ‘Europeanize’ the dispute indicated that Russia’s ‘immediate intervention’ need not be anticipated.

Berchtold made his position clear in Vienna that afternoon: ‘the very existence of Austria-Hungary as a Great Power’ was at stake; Austria-Hungary must give proof of its stature as a Great Power ‘by an outright coup de force’. When the Russian chargé d’affaires asked him how Austria would respond if the time limit were to expire without a satisfactory answer from Serbia, Berchtold replied that the Austrian minister and his staff had been instructed in such circumstances to leave Belgrade and return to Austria. Prince Kudashev, after reflecting on this, exclaimed ‘Alors c’est la guerre!’

Gordon Martel is a leading authority on war, empire, and diplomacy in the modern age. His numerous publications include studies of the origins of the first and second world wars, modern imperialism, and the nature of diplomacy. A founding editor of The International History Review, he has taught at a number of Canadian universities, and has been a visiting professor or fellow in England, Ireland and Australia. Editor-in-chief of the five-volume Encyclopedia of War, he is also joint editor of the longstanding Seminar Studies in History series. His new book is The Month That Changed The World: July 1914.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only history articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

The post The month that changed the world: Friday, 24 July 1914 appeared first on OUPblog.

By: PennyF,

on 6/26/2014

Blog:

OUPblog

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

Books,

History,

war,

World,

world war I,

timeline,

month,

British,

Diplomacy,

Europe,

july,

wwi,

first world war,

1914,

empire,

infographic,

*Featured,

Images & Slideshows,

UKpophistory,

Archduke Franz Ferdinand,

gordon martel,

july 1914,

the month that changed the world,

world war I centennial,

martel,

centennial’,

centenary’,

Add a tag

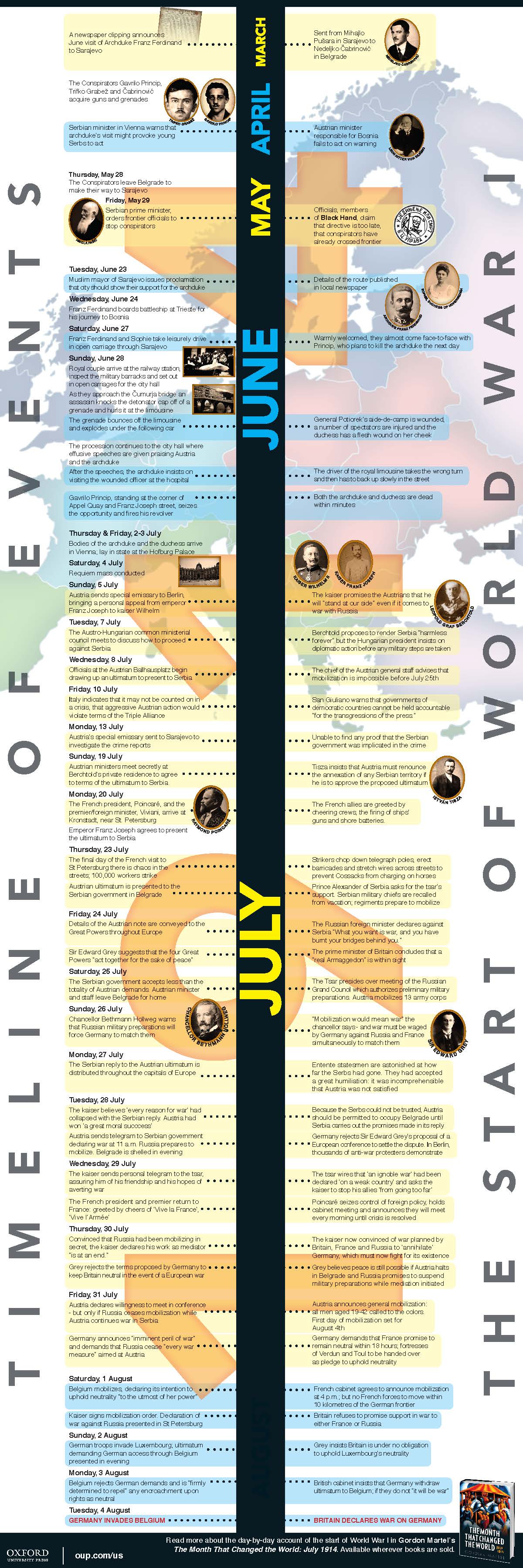

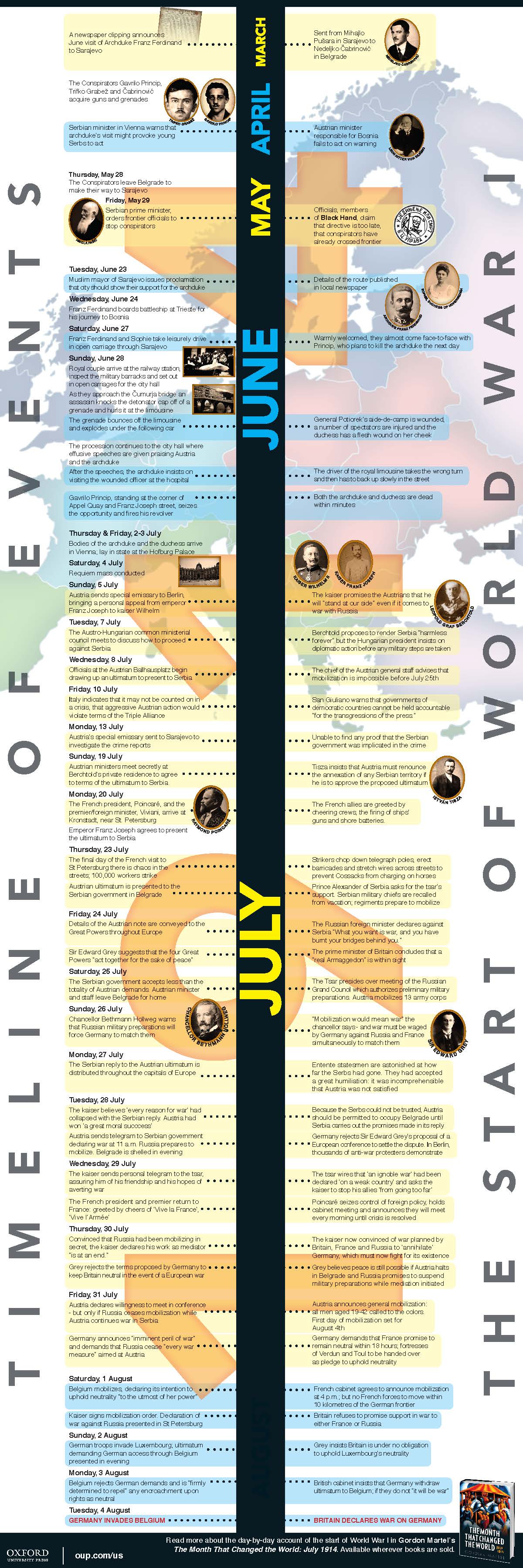

In honor of the centennial of World War I, we’re remembering the momentous period of history that forever changed the world as we know it. July 1914 was the month that changed the world. On 28 June 1914, Archduke Franz Ferdinand was assassinated, and just five weeks later the Great Powers of Europe were at war. But how did it all happen? Historian Gordon Martel, author of The Month That Changed The World: July 1914, will be blogging regularly for us over the next few weeks, giving us a week-by-week and day-by-day account of the events that led up to the First World War. Before we dive in, here’s a timeline that provides an expansive overview of the monumental dates to remember.

Download a jpeg or PDF of the timeline.

Gordon Martel is the author of The Month that Changed the World: July 1914. He is a leading authority on war, empire, and diplomacy in the modern age. His numerous publications include studies of the origins of the first and second world wars, modern imperialism, and the nature of diplomacy. A founding editor of The International History Review, he has taught at a number of Canadian universities, and has been a visiting professor or fellow in England, Ireland and Australia. Editor-in-Chief of the five-volume Encyclopedia of War, he is also Joint Editor of the longstanding Seminar Studies in History series.

Visit the US ‘World War I: Commemorating the Centennial’ page or UK ‘First World War Centenary’ page to discover specially commissioned contributions from our expert authors, free resources from our world-class products, book lists, and exclusive archival materials that provide depth, perspective and insight into the Great War.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only history articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

The post The month that changed the world: a timeline to war appeared first on OUPblog.