July 1914 was the month that changed the world. On 28 June 1914, Archduke Franz Ferdinand was assassinated, and just five weeks later the Great Powers of Europe were at war. But how did it all happen? Historian Gordon Martel, author of The Month That Changed The World: July 1914, is blogging regularly for us over the next few weeks, giving us a week-by-week and day-by-day account of the events that led up to the First World War.

By Gordon Martel

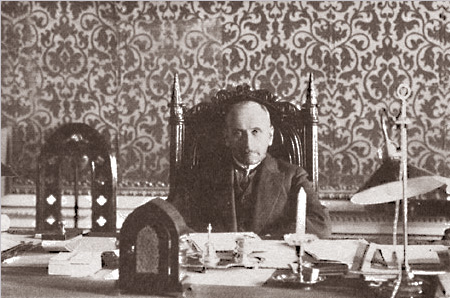

As the day began a diplomatic solution to the crisis appeared to be within sight at last. The German chancellor had insisted that Austria agree to negotiate directly with Russia. While Germany was prepared to fulfill the obligations of its alliance with Austria, it would decline ‘to be drawn wantonly into a world conflagration by Vienna’. Bethmann Hollweg was also promising to support Sir Edward Grey’s proposed conference to mediate the dispute. He told the Austrians that their political prestige and military honour could be satisfied by an occupation of Belgrade. They could enhance their status in the Balkans while strengthening themselves against the Russians through the humiliation of Serbia.

But a third initiative, the direct line of communication between the Kaiser and the Tsar, was running aground. Attempting to reassure Wilhelm, Nicholas explained that the military measures now being undertaken had been decided upon five days ago – and only as a defence against Austria’s preparations. ‘I hope from all my heart that these measures won’t in any way interfere with your part as mediator which I greatly value.’

Theobald von Bethmann Hollweg, Chancellor of the German Empire, 1909-1917. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

The German ambassador in Vienna presented Bethmann’s directive to a ‘pale and silent’ Berchtold over breakfast. Austria, with guarantees of Serbia’s good behaviour in the future as part of the mediation proposal, could attain its aims ‘without unleashing a world war’. To refuse mediation completely ‘was out of the question’.

Berchtold did as he was told. He explained to the Russians that his apparent rejection of mediation talks was an unfortunate misunderstanding and that he was now prepared to discuss ‘amicably and confidentially’ all questions directly affecting their relations. He warned, however, that he would not yield on any of points in the note to Serbia.

At noon, Russia announced that it was initiating a partial mobilization. But the Austrian ambassador assured Vienna that this was a bluff: Sazonov dreaded war ‘as much as his Imperial Master’ and was attempting ‘to deprive us of the fruits of our Serbian campaign without going to Serbia’s aid if possible’.

In Berlin, the chief of the German general staff began to panic. A few hours after the Russian announcement he pleaded with the Austrians to mobilize fully against Russia and to announce this in a public proclamation. The only way to preserve Austria-Hungary was to endure a European war. ‘Germany is with you unconditionally’. Moltke promised that a German mobilization would immediately follow Austria’s.

In St. Petersburg the war minister and the chief of the general staff tried to persuade Nicholas over the telephone that partial mobilization was a mistake. The Tsar refused to budge. When Sazonov met with the Tsar at Peterhof at 3 p.m. he argued that general mobilization was essential; war was almost inevitable because the Germans were resolved to bring it about. They could easily have made the Austrians see reason if they had desired peace. The Tsar gave way. At 5 p.m. the official decree announcing general mobilization was issued.

In Paris the French cabinet was also deciding to take military steps. They agreed that – for the sake of public opinion – they must take care that ‘the Germans put themselves in the wrong’. They would try to avoid the appearance of mobilizing while consenting to at least some of the requests being made by the army. Covering troops could take up their positions along the German frontier from Luxembourg to the Vosges mountains, but were not to approach closer than 10 kilometres. No train transport was to be used, no reservists were to be called up, no horses or vehicles were to be requisitioned. Joffre, the chief of the general staff, was displeased. These measures would make it difficult to execute the offensive thrust of his war plan. Nevertheless, the orders went out at 4.55 p.m.

In London Grey bluntly rejected Bethmann’s neutrality proposal of the day before: ‘that we should bind ourselves to neutrality on such terms cannot for a moment be entertained’. Germany was asking Britain to stand by while French colonies were taken and France was beaten in exchange for Germany’s promise to refrain from taking French territory in Europe. Such a proposal was unacceptable ‘for France could be so crushed as to lose her position as a Great Power, and become subordinate to German policy’. On the other hand, if the current crisis passed and the peace of Europe preserved, Grey promised to endeavour to promote an arrangement by which Germany could be assured ‘that no hostile or aggressive policy would be pursued against her or her allies by France, Russia, and ourselves, jointly or separately’.

Shortly before midnight a telegram from King George arrived at Potsdam. Responding to an earlier telegram from the Kaiser’s brother, the King assured him that the British government was doing its utmost to persuade Russia and France to suspend further military preparations. This seemed possible ‘if Austria will consent to be satisfied with [the] occupation of Belgrade and neighbouring Servian territory as a hostage for [the] satisfactory settlement of her demands’. He urged the Kaiser to use his great influence at Vienna to induce Austria to accept this proposal and prove that Germany and Britain were working together to prevent a catastrophe.

The Kaiser ordered his brother to drive into Berlin immediately to inform Bethmann Hollweg of the news. Heinrich delivered the message to the chancellor at 1.15 a.m. and had returned to Potsdam by 2.20. Wilhelm planned to answer the King on Friday morning. The Kaiser noted, happily, that the suggestions made by the King were the same as those he had proposed to Vienna that evening.

Surely a peaceful resolution was at hand?

Gordon Martel is a leading authority on war, empire, and diplomacy in the modern age. His numerous publications include studies of the origins of the first and second world wars, modern imperialism, and the nature of diplomacy. A founding editor of The International History Review, he has taught at a number of Canadian universities, and has been a visiting professor or fellow in England, Ireland and Australia. Editor-in-chief of the five-volume Encyclopedia of War, he is also joint editor of the longstanding Seminar Studies in History series. His new book is The Month That Changed The World: July 1914.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only history articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

The post The month that changed the world: Thursday, 30 July 1914 appeared first on OUPblog.