new posts in all blogs

Viewing: Blog Posts Tagged with: the july crisis, Most Recent at Top [Help]

Results 1 - 6 of 6

How to use this Page

You are viewing the most recent posts tagged with the words: the july crisis in the JacketFlap blog reader. What is a tag? Think of a tag as a keyword or category label. Tags can both help you find posts on JacketFlap.com as well as provide an easy way for you to "remember" and classify posts for later recall. Try adding a tag yourself by clicking "Add a tag" below a post's header. Scroll down through the list of Recent Posts in the left column and click on a post title that sounds interesting. You can view all posts from a specific blog by clicking the Blog name in the right column, or you can click a 'More Posts from this Blog' link in any individual post.

By: Kirsty,

on 8/3/2014

Blog:

OUPblog

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

Books,

History,

World,

Belgium,

world war I,

British,

This Day in History,

Europe,

belgian,

wwi,

first world war,

*Featured,

UKpophistory,

gordon martel,

july 1914,

the month that changed the world,

Sir Edward Grey,

Poincaré,

the july crisis,

declaration of war,

august 1914,

British cabinet,

coasts,

garitan,

brocqueville,

Add a tag

July 1914 was the month that changed the world. On 28 June 1914, Archduke Franz Ferdinand was assassinated, and just five weeks later the Great Powers of Europe were at war. But how did it all happen? Historian Gordon Martel, author of The Month That Changed The World: July 1914, has been blogging regularly for us over the past few weeks, giving us a week-by-week and day-by-day account of the events that led up to the First World War.

By Gordon Martel

At 7 a.m. Monday morning the reply of the Belgian government was handed to the German minister in Brussels. The German note had made ‘a deep and painful impression’ on the government. France had given them a formal declaration that it would not violate Belgian neutrality, and, if it were to do so, ‘the Belgian army would offer the most vigorous resistance to the invader’. Belgium had always been faithful to its international obligations and had left nothing undone ‘to maintain and enforce respect’ for its neutrality. The attack on Belgian independence which Germany was now threatening ‘constitutes a flagrant violation of international law’. No strategic interest could justify this. ‘The Belgian Government, if they were to accept the proposals submitted to them, would sacrifice the honour of the nation and betray at the same time their duties towards Europe.’

When the British cabinet reconvened later that morning at 11 a.m. there were now four ministers prepared to resign over the issue of British intervention. Their discussion lasted for three hours, at the end of which they agreed on the line to be taken by Sir Edward Grey when he addressed the House of Commons at 3 p.m. ‘The Cabinet was very moving. Most of us could hardly speak at all for emotion.’

Grey began his address to the House by explaining that the present crisis differed from that of Morocco in 1912. That had been a dispute which involved France primarily, to whom Britain had promised diplomatic support, and had done so publicly. The situation they faced now had originated as a dispute between Austria and Serbia – one in which France had become engaged because it was obligated by honour to do so as a result of its alliance with Russia. But this obligation did not apply to Britain. ‘We are not parties to the Franco-Russian Alliance. We do not even know the terms of that Alliance.’

But, because of their now-established friendship, the French had concentrated their fleet in the Mediterranean because they were secure in the knowledge that they need not fear for the safety of their northern and western coasts. Those coasts were now absolutely undefended. ‘My own feeling is that if a foreign fleet engaged in a war which France had not sought, and in which she had not been the aggressor, came down the English Channel and bombarded and battered the undefended coasts of France, we could not stand aside and see this going on practically within sight of our eyes, with our arms folded, looking on dispassionately, doing nothing!’ The government felt strongly that France was entitled to know ‘and to know at once!’ whether in the event of an attack on her coasts it could depend on British support. Thus, he had given the government’s assurance of support to the French ambassador yesterday.

There was another, more immediate consideration: what should Britain do in the event of a violation of Belgian neutrality? He warned the House that if Belgium’s independence were to go, that of Holland would follow. And what…

‘If France is beaten in a struggle of life and death, beaten to her knees, loses her position as a great Power, becomes subordinate to the will and power of one greater than herself’? If Britain chose to stand aside and ‘run away from those obligations of honour and interest as regards the Belgian Treaty, I doubt whether, whatever material force we might have at the end, it would be of very much value…’

‘I do not believe for a moment, that at the end of this war, even if we stood aside and remained aside, we should be in a position, a material position, to use our force decisively to undo what had happened in the course of the war, to prevent the whole of the West of Europe opposite to us—if that had been the result of the war—falling under the domination of a single Power, and I am quite sure that our moral position would be such as to have lost us all respect.’

While Grey was speaking in the House the king and queen were driving along the Mall to Buckingham Palace in an open carriage, cheered by large crowds. In Berlin the Russian ambassador was being attacked by a mob wielding sticks, while the German chancellor was sending instructions to the ambassador in Paris to inform the French government that Germany considered itself to now be ‘in a state of war’ with France. At 6 p.m. the declaration was handed in at Paris:

‘The German administrative and military authorities have established a certain number of flagrantly hostile acts committed on German territory by French military aviators. Several of these have openly violated the neutrality of Belgium by flying over the territory of that country; one has attempted to destroy buildings near Wesel; others have been seen in the district of the Eifel, one has thrown bombs on the railway near Karlsruhe and Nuremberg.’

The French president welcomed the declaration. It came as a relief, Poincaré said, given that war was by this time inevitable.

‘It is a hundred times better that we were not led to declare war ourselves, even on account of repeated violations of our frontier…. If we had been forced to declare war ourselves, the Russian alliance would have become a subject of controversy in France, national [élan?] would have been broken, and Italy may have been forced by the provisions of the Triple Alliance to take sides against us.’

When the British cabinet met again briefly in the evening they had before them the text of the German ultimatum to Belgium and the Belgian reply to it. They agreed to insist that the German government withdraw the ultimatum. After the meeting Grey told the French ambassador that if Germany refused ‘it will be war’.

Gordon Martel is a leading authority on war, empire, and diplomacy in the modern age. His numerous publications include studies of the origins of the first and second world wars, modern imperialism, and the nature of diplomacy. A founding editor of The International History Review, he has taught at a number of Canadian universities, and has been a visiting professor or fellow in England, Ireland and Australia. Editor-in-chief of the five-volume Encyclopedia of War, he is also joint editor of the longstanding Seminar Studies in History series. His new book is The Month That Changed The World: July 1914.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only history articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

The post The month that changed the world: Monday, 3 August 1914 appeared first on OUPblog.

By: Kirsty,

on 8/2/2014

Blog:

OUPblog

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

Books,

History,

World,

world war I,

British,

This Day in History,

Europe,

wwi,

first world war,

Lloyd George,

*Featured,

Luxembourg,

UKpophistory,

gordon martel,

july 1914,

the month that changed the world,

Asquith,

Sir Edward Grey,

the july crisis,

Paul Cambon,

Treaty of London of 1867,

Add a tag

July 1914 was the month that changed the world. On 28 June 1914, Archduke Franz Ferdinand was assassinated, and just five weeks later the Great Powers of Europe were at war. But how did it all happen? Historian Gordon Martel, author of The Month That Changed The World: July 1914, has been blogging regularly for us over the past few weeks, giving us a week-by-week and day-by-day account of the events that led up to the First World War.

By Gordon Martel

Confusion was still widespread on the morning of 2 August 1914. On Saturday Germany and France had joined Austria-Hungary and Russia in announcing their general mobilization; by 7 p.m. Germany appeared to be at war with Russia. Still, the only shots fired in anger consisted of the bombs that the Austrians continued to shower on Belgrade. Sir Edward Grey continued to hope that the German and French armies might agree on a standstill behind their frontiers while Russia and Austria proceeded to negotiate a settlement over Serbia. No one was certain what the British would do – especially not the British.

Shortly after dawn Sunday German troops crossed the frontier into the Grand Duchy of Luxembourg. Trains loaded with soldiers crossed the bridge at Wasserbillig and headed to the city of Luxembourg, the capital of the Grand-Duchy. By 8.30 a.m. German troops occupied the railway station in the city centre. Marie-Adélaïde, the grand duchess, protested directly to the kaiser, demanding an explanation and asking him to respect the country’s rights. The chancellor replied that Germany’s military measures should not be regarded as hostile, but only as steps to protect the railways under German management against an attack by the French; he promised full compensation for any damages suffered.

The neutrality of Luxembourg had been guaranteed by the Powers in the Treaty of London of 1867. The prime minister immediately protested the violation at Berlin, Paris, London, and Brussels. When Paul Cambon received the news in London at 7.42 a.m. he requested a meeting with Sir Edward Grey. The French ambassador brought with him a copy of the 1867 treaty – but Grey took the position that the treaty was a ‘collective instrument’, meaning that if Germany chose to violate it, Britain was released from any obligation to uphold it. Disgusted, Cambon declared that the word ‘honour’ might have ‘to be struck out of the British vocabulary’.

The cabinet was scheduled to meet at 10 Downing Street at 11 a.m. Before it convened Lloyd George held a small meeting of his own at the chancellor’s residence next door with five other members of cabinet. They were untroubled by the German invasion of Luxembourg and agreed that, as a group, they would oppose Britain’s entry into the war in Europe. They might reconsider under certain circumstances, however, ‘such as the invasion wholesale of Belgium’.

When they met the cabinet found it almost impossible to decide under what conditions Britain should intervene. Opinions ranged from opposition to intervention under any circumstances to immediate mobilization of the army in anticipation of despatching the British Expeditionary Force to France. Grey revealed his frustration with Germany and Austria-Hungary: they had chosen to play with the most vital interests of civilization and had declined the numerous attempts he had made to find a way out of the crisis. While appearing to negotiate they had continued their march ‘steadily to war’. But the views of the foreign secretary proved unacceptable to the majority of the cabinet. Asquith believed they were on the brink of a split.

After almost three hours of heated debate the cabinet finally agreed to authorize Grey to give the French a qualified assurance. The British government would not permit the Germans to make the English Channel the base for hostile operations against the French.

While the cabinet was meeting in the afternoon a great anti-war demonstration was beginning only a few hundred yards away in Trafalgar Square. Trade unions organized a series of processions, with thousands of workers marching to meet at Nelson’s column from St George’s circus, the East India Docks, Kentish Town, and Westminster Cathedral. Speeches began around 4 p.m. – by which time 10-15,000 had gathered to hear Keir Hardie and other labour leaders, socialists and peace activists. With rain pouring down, at 5 p.m. a resolution in favour of international peace and for solidarity among the workers of the world ‘to use their industrial and political power in order that the nations shall not be involved in the war’ was put to the crowd and deemed to have carried.

If the British cabinet was divided, so however were the people of London. When the crowd began singing ‘The Red Flag’ and the ‘Internationale’ they were matched by anti-socialists and pro-war demonstrators singing ‘God Save the King’ and ‘Rule Britannia’. When a red flag was hoisted, a Union Jack went up in reply. Part of the crowd broke away and marched a few hundred feet to Admiralty Arch where they listened to patriotic speeches. Several thousand marched up the Mall to Buckingham Palace, singing the national anthem and the Marseillaise. The King and the Queen appeared on the balcony to acknowledge the cheering crowd. Later that evening demonstrators gathered in front of the French embassy to show their support.

The anti-war sentiment, which was still strong among labour groups and socialist organizations in Britain, was rapidly dissipating in France. On Sunday morning the Socialist party announced its intention to defend France in the event of war. The newspaper of the syndicalist CGT declared ‘That the name of the old emperor Franz Joseph be cursed’; it denounced the kaiser ‘and the pangermanists’ as responsible for the war. In Germany three large trade unions did a deal with the government: in exchange for promising not to go on strike, the government promised not to ban them. In Russia, organized opposition to war practically disappeared.

Shortly before dinner that evening the British cabinet met once again to decide whether they were prepared to enter the war. The prime minister had received a promise from the leader of the Unionist opposition, Andrew Bonar Law, that his party would support Britain’s entry into the war. Now, if the anti-war sentiment in cabinet led to the resignation of Sir Edward Grey – and most likely of Asquith, Churchill and several others along with him – there loomed the likelihood of a coalition government being formed that would lead Britain into war anyway.

While the British cabinet were meeting in London they were unaware that the German minister at Brussels was presenting an ultimatum to the Belgian government at 7.00 p.m. The note contained in the envelope claimed that the German government had received reliable information that French forces were preparing to march through Belgian territory in order to attack Germany. Germany feared that Belgium would be unable to resist a French invasion. For the sake of Germany’s self-defence it was essential that it anticipate such an attack, which might necessitate German forces entering Belgian territory. Belgium was given until 7 a.m. the next morning – twelve hours – to respond.

Within the hour the prime minister took the German note to the king. They agreed that Belgium could not agree to the demands. The king called his council of ministers to the palace at 9 p.m. where they discussed the situation until midnight. The council agreed unanimously with the position taken by the king and the prime minister. They recessed for an hour, resuming their meeting at 1 a.m. to draft a reply.

Gordon Martel is a leading authority on war, empire, and diplomacy in the modern age. His numerous publications include studies of the origins of the first and second world wars, modern imperialism, and the nature of diplomacy. A founding editor of The International History Review, he has taught at a number of Canadian universities, and has been a visiting professor or fellow in England, Ireland and Australia. Editor-in-chief of the five-volume Encyclopedia of War, he is also joint editor of the longstanding Seminar Studies in History series. His new book is The Month That Changed The World: July 1914.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only history articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

The post The month that changed the world: Sunday, 2 August 1914 appeared first on OUPblog.

By: Kirsty,

on 7/28/2014

Blog:

OUPblog

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

*Featured,

UKpophistory,

gordon martel,

july 1914,

the month that changed the world,

the july crisis,

WWI centenary,

declaration of war,

Kaiser Wilhelm,

austro,

Books,

History,

military history,

World,

world war I,

British,

Diplomacy,

This Day in History,

Europe,

wwi,

belgrade,

first world war,

Add a tag

July 1914 was the month that changed the world. On 28 June 1914, Archduke Franz Ferdinand was assassinated, and just five weeks later the Great Powers of Europe were at war. But how did it all happen? Historian Gordon Martel, author of The Month That Changed The World: July 1914, is blogging regularly for us over the next few weeks, giving us a week-by-week and day-by-day account of the events that led up to the First World War.

By Gordon Martel

Kaiser Wilhelm received a copy of the Serbian reply to the Austrian demands in the morning. Reading it over, he concluded that the Habsburg monarchy had achieved its aims and that the few points Serbia objected to could be settled by negotiation. Their submission represented a humiliating capitulation, and with it ‘every cause for war’ collapsed. A diplomatic solution to the crisis was now clearly within sight. Austria-Hungary would emerge triumphant: the Serbian reply represented ‘a great moral success for Vienna’.

In order to assure Austria’s success, to turn the ‘beautiful promises’ of the Serbs into facts, the Kaiser proposed that Belgrade should be taken and held hostage by Austria. ‘The Serbs,’ he pointed out, ‘are Orientals, and therefore liars, fakers and masters of evasion.’ An occupation of Belgrade would guarantee that the Serbs would carry out their promises while satisfying satisfying the honour of the Austro-Hungarian army. On this basis the Kaiser was willing to ‘mediate’ with Austria in order to preserve European peace.

In Vienna that morning the German ambassador was instructed to explain that Germany could not continue to reject every proposal for mediation. To do so was to risk being seen as the instigator of the war and being held responsible by the whole world for the conflagration that would follow.

Berchtold began to worry that German support was about to evaporate. He responded by getting the emperor to agree to issue a declaration of war on Serbia just before noon. For the first time in history war was declared by the sending of a telegram.

The bombardment of Belgrade by Austro-Hungarian monitor. By Horace Davis. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons

The German chancellor undertook a new initiative to place the responsibility for a European war on Russia: he encouraged Kaiser to write directly to the Tsar, to appeal to his monarchical sensibilities. Such a telegram would ‘throw the clearest light on Russia’s responsibility’. At the same time he rejected Sir Edward Grey’s proposal for a conference in London in favour of ‘mediation efforts’ at St Petersburg, and trusted that his ambassador in London could get Grey ‘to see our point of view’.

At the Foreign Office in London they were skeptical. Officials concluded that the Austrians were determined to find the Serbian reply unsatisfactory, that if Austria demanded absolute compliance with its ultimatum ‘it can only mean that she wants a war’. What Austria was demanding amounted to a protectorate. Grey denied the German complaint that he was proposing an ‘arbitration’ – what he was suggesting was a ‘private and informal discussion’ that might lead to suggestion for settlement. But he agreed to suspend his proposal as long as there was a chance that the ‘bilateral’ Austro-Russian talks might succeed.

The news that Austria-Hungary had declared war on Serbia reached Sazonov in St Petersburg late that afternoon. He immediately arranged to meet with the Tsar at the Peterhof. After their meeting the foreign minister instructed the Russian chief of the general staff to draft two ukazes – one for partial mobilization of the four military districts of Odessa, Kiev, Moscow and Kazan, another for general mobilization. But the Tsar, who remained steadfast in his determination to do nothing that might antagonize Germany, would go no further than authorize a partial mobilization aimed at Austria-Hungary. He did so in spite of the warnings from his military advisers who told him that such a mobilization was impossible: a partial mobilization would result in chaos, make it impossible to prosecute a successful war against Austria-Hungary and render Russia vulnerable in a war with Germany.

A partial mobilization would, however, serve the requirements of Russian diplomacy. Sazonov attempted to placate the Germans by assuring them that the decision to mobilize in only the four districts indicated that Russia had no intention of attacking them. Keeping the door open for negotiations, he decided not to recall the Russian ambassador from Vienna – in spite of Austria’s declaration of war on Serbia. Perhaps there was still time for the bilateral talks in St Petersburg to save the situation.

That night Belgrade was bombarded by Austro-Hungarian artillery: two shells exploded in a school, one at the Grand Hotel, others at cafés and banks. Offices, hotels, and banks had been closed. The city had been left defenceless.

Gordon Martel is a leading authority on war, empire, and diplomacy in the modern age. His numerous publications include studies of the origins of the first and second world wars, modern imperialism, and the nature of diplomacy. A founding editor of The International History Review, he has taught at a number of Canadian universities, and has been a visiting professor or fellow in England, Ireland and Australia. Editor-in-chief of the five-volume Encyclopedia of War, he is also joint editor of the longstanding Seminar Studies in History series. His new book is The Month That Changed The World: July 1914.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only history articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

The post The month that changed the world: Tuesday, 28 July 1914 appeared first on OUPblog.

By: Kirsty,

on 7/27/2014

Blog:

OUPblog

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

Europe,

wwi,

first world war,

*Featured,

UKpophistory,

gordon martel,

july 1914,

the month that changed the world,

the july crisis,

WWI centenary,

Books,

History,

military history,

World,

world war I,

British,

This Day in History,

Add a tag

July 1914 was the month that changed the world. On 28 June 1914, Archduke Franz Ferdinand was assassinated, and just five weeks later the Great Powers of Europe were at war. But how did it all happen? Historian Gordon Martel, author of The Month That Changed The World: July 1914, is blogging regularly for us over the next few weeks, giving us a week-by-week and day-by-day account of the events that led up to the First World War.

By Gordon Martel

By the time the diplomats, politicians, and officials arrived at their offices in the morning more than 36 hours had elapsed since the Austrian deadline to Serbia had expired. And yet nothing much had happened as a consequence: the Austrian legation had packed up and left Belgrade; Austria had severed diplomatic relations with Serbia and announced a partial mobilization; but there had been no declaration of war, no shots fired in anger or in error, no wider mobilization of European armies. What action there was occurred behind the scenes, at the Foreign Office, the Ballhausplatz, the Wilhelmstrasse, the Consulta, the Quai d’Orsay, and at the Chorister’s Bridge.

Some tentative, precautionary, steps were taken. In Russia, all lights along the coast of the Black Sea were ordered to be extinguished; the port of Sevastopol was closed to all but Russian warships; flights were banned over the military districts of St Petersburg, Vilna, Warsaw, Kiev, and Odessa. In France, over 100,000 troops stationed in Morocco and Algeria were ordered to metropolitan France; the French president and premier were asked to sail for home immediately. In Britain the cabinet agreed to keep the First and Second fleets together following manoeuvres; Winston Churchill, First Lord of the Admiralty, notified his naval commanders that war between the Triple Alliance and the Triple Entente was ‘by no means impossible’. In Germany all troops were confined to barracks. On the Danube, Hungarian authorities seized two Serbian vessels.

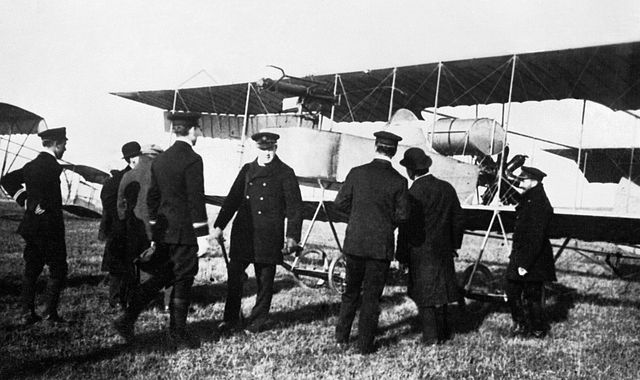

Winston Churchill with the Naval Wing of the Royal Flying Corps, 1914. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

Throughout the day the Serbian reply to the Austrian ultimatum was communicated throughout Europe. Austria appeared to have won great diplomatic victory. Sir Edward Grey thought the Serbs had gone farther to placate the Austrians than he had believed possible: if the Austrians refused to accept the Serbian reply as the foundation for peaceful negotiations it would be ‘absolutely clear’ that they were only seeking an excuse to crush Serbia. If so, Russia was bound to regard it as a direct challenge and the result ‘would be the most frightful war that Europe had ever seen’.

The German chancellor concluded that Serbia had complicated things by accepting almost all of the demands and that Austria was close to accomplishing everything that it wanted. The Kaiser who arrived in Kiel that morning, presided over a meeting in Potsdam at 3 p.m. where he, the chancellor, the chief of the general staff, and several more generals reviewed the situation. No dramatic decisions were taken. General Hans von Plessen, the adjutant general, recorded that they still hoped to localize the war, and that Britain seemed likely to remain neutral: ‘I have the impression that it will all blow over’.

The question of the day, then, was whether Austria would be satisfied with a resounding diplomatic victory. Russia seemed prepared to offer them one. In St Petersburg on Monday Sazonov promised to go ‘to the limit’ in accommodating them if it brought the crisis to a peaceful conclusion. He promised the German ambassador that he would they ‘build a golden bridge’ for the Austrians, that he had ‘no heart’ for the Balkan Slavs, and that he saw no problem with seven of the ten Austrian demands.

In Vienna however, Berchtold dismissed Serbia’s promises as totally worthless. Austria, he promised, would declare war the next day, or by Wednesday at the latest – in spite of the chief of the general staff’s insistence that war operations against Serbia could not begin for two weeks.

Grey was distressed to hear that Austria would treat the Serb reply as if it were a ‘decided refusal’ to comply with Austria’s wishes. The ultimatum was ‘really the greatest humiliation to which an independent State has ever been subjected’ and was surely enough to serve as foundation of a settlement.

By the end of the day on Monday, uncertainty was still widespread. Two separate proposals for reaching a settlement were now on the table: Grey’s renewed suggestion for à quatre discussions in London, and Sazonov’s new suggestion for bilateral discussions with Austria in St Petersburg. Germany had indicated that it was encouraging Austria to consider both suggestions. The German ambassador told Berlin that if Grey’s suggestion succeeded in settling the crisis with Germany’s co-operation, ‘I will guarantee that our relations with Great Britain will remain, for an incalculable time to come, of the same intimate and confidential character that has distinguished them for the last year and a half’. On the other hand, if Germany stood behind Austria and subordinated its good relations with Britain to the special interests of its ally, ‘it would never again be possible to restore those ties which have of late bound us together’.

Gordon Martel is a leading authority on war, empire, and diplomacy in the modern age. His numerous publications include studies of the origins of the first and second world wars, modern imperialism, and the nature of diplomacy. A founding editor of The International History Review, he has taught at a number of Canadian universities, and has been a visiting professor or fellow in England, Ireland and Australia. Editor-in-chief of the five-volume Encyclopedia of War, he is also joint editor of the longstanding Seminar Studies in History series. His new book is The Month That Changed The World: July 1914.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only history articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

The post The month that changed the world: Monday, 27 July 1914 appeared first on OUPblog.

By: Kirsty,

on 7/26/2014

Blog:

OUPblog

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

Books,

History,

war,

military history,

World,

British,

This Day in History,

Europe,

wwi,

World War One,

first world war,

*Featured,

kaiser,

UKpophistory,

gordon martel,

july 1914,

the month that changed the world,

martel,

the july crisis,

WWI centenary,

Add a tag

July 1914 was the month that changed the world. On 28 June 1914, Archduke Franz Ferdinand was assassinated, and just five weeks later the Great Powers of Europe were at war. But how did it all happen? Historian Gordon Martel, author of The Month That Changed The World: July 1914, is blogging regularly for us over the next few weeks, giving us a week-by-week and day-by-day account of the events that led up to the First World War.

By Gordon Martel

When day dawned on Sunday, 26 July, the sky did not fall. Shells did not rain down on Belgrade. There was no Austrian declaration of war. The morning remained peaceful, if not calm. Most Europeans attended their churches and prepared to enjoy their day of rest. Few said prayers for peace; few believed divine intervention was necessary. Europe had weathered many storms over the last decade. Only pessimists doubted that this one could be weathered as well.

In Austria-Hungary the right of assembly, the secrecy of the mail, of telegrams and telephone conversations, and the freedom of the press were all suspended. Pro-war demonstrations were not only permitted but encouraged: demonstrators filled the Ringstrasse, marched on the Ballhausplatz, gathered around statues of national heroes and sang patriotic songs. That evening the Bürgermeister of Vienna told a cheering crowd that the fate of Europe for centuries to come was about to be decided, praising them as worthy descendants of the men who had fought Napoleon. The Catholic People’s Party newspaper, Alkotmány, declared that ‘History has put the master’s cane in the Monarchy’s hands. We must teach Serbia, we must make justice, we must punish her for her crimes.’

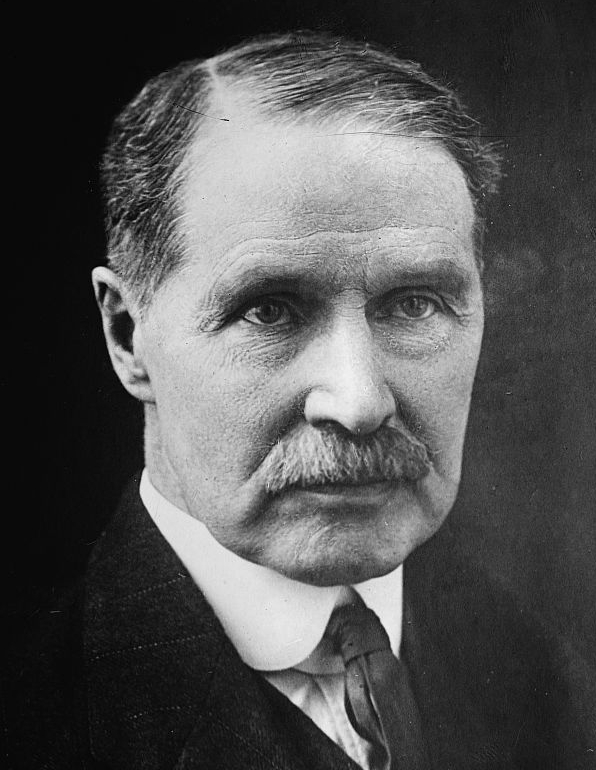

Kaiser Wilhelm

Just how urgent was the situation? In London, Sir Edward Grey had left town on Saturday afternoon to go to his cottage for a day of fly-fishing on Sunday. The Russian ambassadors to Germany, Austria and Paris had yet to return to their posts. The British ambassadors to Germany and Paris were still on vacation. Kaiser Wilhelm was on his annual yachting cruise of the Baltic. Emperor Franz Joseph was at his hunting lodge at Bad Ischl. The French premier and president were visiting Stockholm. The Italian foreign minister was still taking his cure at Fiuggi. The chiefs of the German and Austrian general staffs remained on leave; the chief of the Serbian general staff was relaxing at an Austrian spa.

Could calm be maintained? Contradictory evidence seemed to be coming out of St Petersburg. It seemed that some military steps were being initiated – but what these were to be remained uncertain. Sazonov, the Russian foreign minister, met with both the German and Austrian ambassadors on Sunday – and both noted a significant change in his demeanour. He was now ‘much quieter and more conciliatory’. He emphatically insisted that Russia did not desire war and promised to exhaust every means to avoid it. War could be avoided if Austria’s demands stopped short of violating Serbian sovereignty. The German ambassador suggested that Russia and Austria discuss directly a softening of the demands. Sazonov, who agreed immediately to suggest this, was ‘now looking for a way out’. The Germans were assured that only preparatory measures had been undertaken thus far – ‘not a horse and not a reserve had been called to service’.

By late Sunday afternoon, the situation seemed precarious but not hopeless. The German chancellor worried that any preparatory measures adopted by Russia that appeared to be aimed at Germany would force the adoption of counter-measures. This would mean the mobilization of the German army – and mobilization ‘would mean war’. But he continued to hope that the crisis could be ‘localized’ and indicated that he would encourage Vienna to accept Grey’s proposed mediation and/or direct negotiations between Austria and Russia.

By Sunday evening more than 24 hours had passed since the Austrian legation had departed from Belgrade and Austria had severed diplomatic relations with Serbia. Many had assumed that war would follow immediately, but there had been no invasion of Serbia or even a declaration of war. The Austrians, in spite of their apparent firmness in refusing any alteration of the terms or any extension of the deadline, appeared not to know what step to take next, or when additional steps should be taken. When asked, the Austrian chief of staff suggested that any declaration of war ought to be postponed until 12 August. Was Europe really going to hold its breath for two more weeks?

Gordon Martel is a leading authority on war, empire, and diplomacy in the modern age. His numerous publications include studies of the origins of the first and second world wars, modern imperialism, and the nature of diplomacy. A founding editor of The International History Review, he has taught at a number of Canadian universities, and has been a visiting professor or fellow in England, Ireland and Australia. Editor-in-chief of the five-volume Encyclopedia of War, he is also joint editor of the longstanding Seminar Studies in History series. His new book is The Month That Changed The World: July 1914. Read his previous blog posts.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only history articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Image credit: Kaiser Wilhelm, public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

The post The month that changed the world: Sunday, 26 July 1914 appeared first on OUPblog.

By: Kirsty,

on 7/25/2014

Blog:

OUPblog

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

*Featured,

UKpophistory,

gordon martel,

july 1914,

the month that changed the world,

martel,

the july crisis,

WWI centenary,

ischl,

kaiservilla,

tornadoo,

kaiserville,

Books,

History,

military history,

World,

world war I,

austria,

British,

This Day in History,

Europe,

wwi,

first world war,

serbia,

Add a tag

July 1914 was the month that changed the world. On 28 June 1914, Archduke Franz Ferdinand was assassinated, and just five weeks later the Great Powers of Europe were at war. But how did it all happen? Historian Gordon Martel, author of The Month That Changed The World: July 1914, is blogging regularly for us over the next few weeks, giving us a week-by-week and day-by-day account of the events that led up to the First World War.

By Gordon Martel

Would there be war by the end of the day? It certainly seemed possible: the Serbs had only until 6 p.m. to accept the Austrian demands. Berchtold had instructed the Austrian representative in Belgrade that nothing less than full acceptance of all ten points contained in the ultimatum would be regarded as satisfactory. And no one expected the Serbs to comply with the demands in their entirety – least of all the Austrians.

When the Serbian cabinet met that morning they had received advice from Russia, France, and Britain urging them to be as accommodating as possible. No one indicated that any military assistance might be forthcoming. They began drafting a ‘most conciliatory’ reply to Austria while preparing for war: the royal family prepared to leave Belgrade; the military garrison left the city for a fortified town 60 miles south; the order for general mobilization was signed and drums were beaten outside of cafés, calling up conscripts.

Kaiservilla in Bad Ischl, Austria: the summer residence of Emperor Franz Joseph I. Kaiserville, Bad Ischl, Austria. By Blue tornadoo CC-BY-SA-3.0, via Wikimedia Commons

How would Russia respond? That morning the tsar presided over a meeting of the Russian Grand Council where it was agreed to mobilize the thirteen army corps designated to act against Austria. By afternoon ‘the period preparatory to war’ was initiated and preparations for mobilization began in the military districts of Kiev, Odessa, Moscow, and Kazan.

Simultaneously, Sazonov tried to enlist German support in persuading Austria to extend the deadline beyond 6 p.m., arguing that it was a ‘European matter’ not limited to Austria and Serbia. The Germans refused, arguing that to summon Austria to a European ‘tribunal’ would be humiliating and mean the end of Austria as a Great Power. Sazonov insisted that the Austrians were aiming to establish hegemony in the Balkans: after they devoured Serbia and Bulgaria Russia would face them ‘on the Black Sea’. He tried to persuade Sir Edward Grey that if Britain were to join Russia and France, Germany would then pressure Austria into moderation.

How would Britain respond? Sir Edward Grey gave no indication that Britain would stand shoulder-to-shoulder with the Russians in a conflict over Serbia. His only concern seemed to be to contain the crisis, to keep it a dispute between Austria and Serbia. ‘I do not consider that public opinion here would or ought to sanction our going to war over a Servian quarrel’. But if a war between Austria and Serbia were to occur ‘other issues’ might draw Britain in. In the meantime, there was still an opportunity to avert war if the four disinterested powers ‘held the hand’ of their partners while mediating the dispute. But the report he received from St Petersburg was not encouraging: the British ambassador warned that Russia and France seemed determined to make ‘a strong stand’ even if Britain declined to join them.

When the Austrian minister received the Serb reply at 5:58 on Saturday afternoon, he could see instantly that their submission was not complete. He announced that Austria was breaking off diplomatic relations with Serbia and immediately ordered the staff of the delegation to leave for the railway station. By 6:30 the Austrians were on a train bound for the border.

That evening, in the Kaiservilla at Bad Ischl, Franz Joseph signed the orders for mobilization of thirteen army corps. When the news reached Vienna the people greeted it with the ‘wildest enthusiasm’. Huge crowds began to form, gathering at the Ringstrasse and bursting into patriotic songs. The crowds marched around the city shouting ‘Down with Serbia! Down with Russia’. In front of the German embassy they sang ‘Wacht am Rhein’; police had to protect the Russian embassy against the demonstrators. Surely, it would not be long before the guns began firing.

Gordon Martel is a leading authority on war, empire, and diplomacy in the modern age. His numerous publications include studies of the origins of the first and second world wars, modern imperialism, and the nature of diplomacy. A founding editor of The International History Review, he has taught at a number of Canadian universities, and has been a visiting professor or fellow in England, Ireland and Australia. Editor-in-chief of the five-volume Encyclopedia of War, he is also joint editor of the longstanding Seminar Studies in History series. His new book is The Month That Changed The World: July 1914.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only history articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

The post The month that changed the world: Saturday, 25 July 1914 appeared first on OUPblog.