July 1914 was the month that changed the world. On 28 June 1914, Archduke Franz Ferdinand was assassinated, and just five weeks later the Great Powers of Europe were at war. But how did it all happen? Historian Gordon Martel, author of The Month That Changed The World: July 1914, has been blogging regularly for us over the past few weeks, giving us a week-by-week and day-by-day account of the events that led up to the First World War.

By Gordon Martel

At 7 a.m. Monday morning the reply of the Belgian government was handed to the German minister in Brussels. The German note had made ‘a deep and painful impression’ on the government. France had given them a formal declaration that it would not violate Belgian neutrality, and, if it were to do so, ‘the Belgian army would offer the most vigorous resistance to the invader’. Belgium had always been faithful to its international obligations and had left nothing undone ‘to maintain and enforce respect’ for its neutrality. The attack on Belgian independence which Germany was now threatening ‘constitutes a flagrant violation of international law’. No strategic interest could justify this. ‘The Belgian Government, if they were to accept the proposals submitted to them, would sacrifice the honour of the nation and betray at the same time their duties towards Europe.’

When the British cabinet reconvened later that morning at 11 a.m. there were now four ministers prepared to resign over the issue of British intervention. Their discussion lasted for three hours, at the end of which they agreed on the line to be taken by Sir Edward Grey when he addressed the House of Commons at 3 p.m. ‘The Cabinet was very moving. Most of us could hardly speak at all for emotion.’

Grey began his address to the House by explaining that the present crisis differed from that of Morocco in 1912. That had been a dispute which involved France primarily, to whom Britain had promised diplomatic support, and had done so publicly. The situation they faced now had originated as a dispute between Austria and Serbia – one in which France had become engaged because it was obligated by honour to do so as a result of its alliance with Russia. But this obligation did not apply to Britain. ‘We are not parties to the Franco-Russian Alliance. We do not even know the terms of that Alliance.’

But, because of their now-established friendship, the French had concentrated their fleet in the Mediterranean because they were secure in the knowledge that they need not fear for the safety of their northern and western coasts. Those coasts were now absolutely undefended. ‘My own feeling is that if a foreign fleet engaged in a war which France had not sought, and in which she had not been the aggressor, came down the English Channel and bombarded and battered the undefended coasts of France, we could not stand aside and see this going on practically within sight of our eyes, with our arms folded, looking on dispassionately, doing nothing!’ The government felt strongly that France was entitled to know ‘and to know at once!’ whether in the event of an attack on her coasts it could depend on British support. Thus, he had given the government’s assurance of support to the French ambassador yesterday.

There was another, more immediate consideration: what should Britain do in the event of a violation of Belgian neutrality? He warned the House that if Belgium’s independence were to go, that of Holland would follow. And what…

‘If France is beaten in a struggle of life and death, beaten to her knees, loses her position as a great Power, becomes subordinate to the will and power of one greater than herself’? If Britain chose to stand aside and ‘run away from those obligations of honour and interest as regards the Belgian Treaty, I doubt whether, whatever material force we might have at the end, it would be of very much value…’

‘I do not believe for a moment, that at the end of this war, even if we stood aside and remained aside, we should be in a position, a material position, to use our force decisively to undo what had happened in the course of the war, to prevent the whole of the West of Europe opposite to us—if that had been the result of the war—falling under the domination of a single Power, and I am quite sure that our moral position would be such as to have lost us all respect.’

While Grey was speaking in the House the king and queen were driving along the Mall to Buckingham Palace in an open carriage, cheered by large crowds. In Berlin the Russian ambassador was being attacked by a mob wielding sticks, while the German chancellor was sending instructions to the ambassador in Paris to inform the French government that Germany considered itself to now be ‘in a state of war’ with France. At 6 p.m. the declaration was handed in at Paris:

‘The German administrative and military authorities have established a certain number of flagrantly hostile acts committed on German territory by French military aviators. Several of these have openly violated the neutrality of Belgium by flying over the territory of that country; one has attempted to destroy buildings near Wesel; others have been seen in the district of the Eifel, one has thrown bombs on the railway near Karlsruhe and Nuremberg.’

The French president welcomed the declaration. It came as a relief, Poincaré said, given that war was by this time inevitable.

‘It is a hundred times better that we were not led to declare war ourselves, even on account of repeated violations of our frontier…. If we had been forced to declare war ourselves, the Russian alliance would have become a subject of controversy in France, national [élan?] would have been broken, and Italy may have been forced by the provisions of the Triple Alliance to take sides against us.’

When the British cabinet met again briefly in the evening they had before them the text of the German ultimatum to Belgium and the Belgian reply to it. They agreed to insist that the German government withdraw the ultimatum. After the meeting Grey told the French ambassador that if Germany refused ‘it will be war’.

Gordon Martel is a leading authority on war, empire, and diplomacy in the modern age. His numerous publications include studies of the origins of the first and second world wars, modern imperialism, and the nature of diplomacy. A founding editor of The International History Review, he has taught at a number of Canadian universities, and has been a visiting professor or fellow in England, Ireland and Australia. Editor-in-chief of the five-volume Encyclopedia of War, he is also joint editor of the longstanding Seminar Studies in History series. His new book is The Month That Changed The World: July 1914.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only history articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

The post The month that changed the world: Monday, 3 August 1914 appeared first on OUPblog.

By Tony Hope

Science and morality are often seen as poles apart. Doesn’t science deal with facts, and morality with, well, opinions? Isn’t science about empirical evidence, and morality about philosophy? In my view this is wrong. Science and morality are neighbours. Both are rational enterprises. Both require a combination of conceptual analysis, and empirical evidence. Many, perhaps most moral disagreements hinge on disagreements over evidence and facts, rather than disagreements over moral principle.

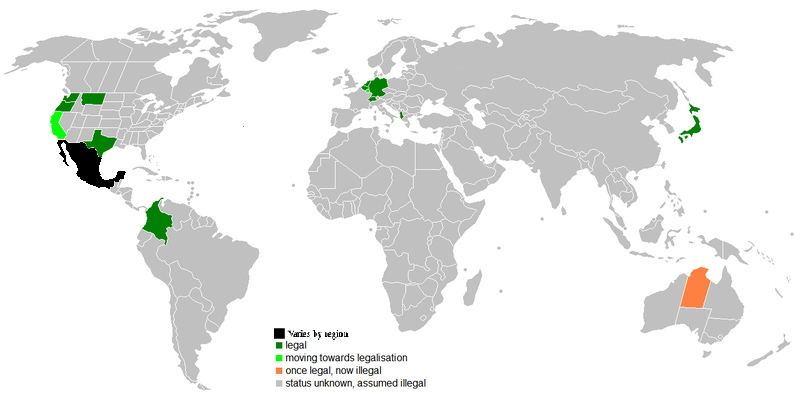

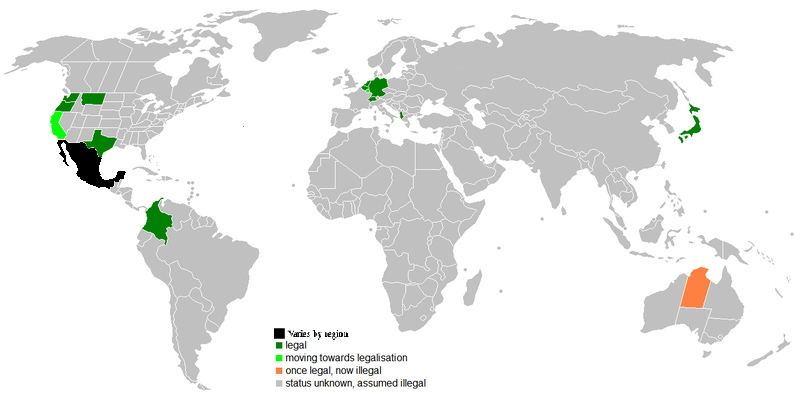

Consider the recent child euthanasia law in Belgium that allows a child to be killed – as a mercy killing – if: (a) the child has a serious and incurable condition with death expected to occur within a brief period; (b) the child is experiencing constant and unbearable suffering; (c) the child requests the euthanasia and has the capacity of discernment – the capacity to understand what he or she is requesting; and, (d) the parents agree to the child’s request for euthanasia. The law excludes children with psychiatric disorders. No one other than the child can make the request.

Is this law immoral? Thought experiments can be useful in testing moral principles. These are like the carefully controlled experiments that have been so useful in science. A lorry driver is trapped in the cab. The lorry is on fire. The driver is on the verge of being burned to death. His life cannot be saved. You are standing by. You have a gun and are an excellent shot and know where to shoot to kill instantaneously. The bullet will be able to penetrate the cab window. The driver begs you to shoot him to avoid a horribly painful death.

Would it be right to carry out the mercy killing? Setting aside legal considerations, I believe that it would be. It seems wrong to allow the driver to suffer horribly for the sake of preserving a moral ideal against killing.

Thought experiments are often criticised for being unrealistic. But this can be a strength. The point of the experiment is to test a principle, and the ways in which it is unrealistic can help identify the factual aspects that are morally relevant. If you and I agree that it would be right to kill the lorry driver then any disagreement over the Belgian law cannot be because of a fundamental disagreement over mercy killing. It is likely to be a disagreement over empirical facts or about how facts integrate with moral principles.

There is a lot of discussion of the Belgian law on the internet. Most of it against. What are the arguments?

Some allow rhetoric to ride roughshod over reason. Take this, for example: “I’m sure the Belgian parliament would agree that minors should not have access to alcohol, should not have access to pornography, should not have access to tobacco, but yet minors for some reason they feel should have access to three grams of phenobarbitone in their veins – it just doesn’t make sense.”

But alcohol, pornography and tobacco are all considered to be against the best interests of children. There is, however, a very significant reason for the ‘three grams of phenobarbitone’: it prevents unnecessary suffering for a dying child. There may be good arguments against euthanasia but using unexamined and poor analogies is just sloppy thinking.

I have more sympathy for personal experience. A mother of two terminally ill daughters wrote in the Catholic Herald: “Through all of their suffering and pain the girls continued to love life and to make the most of it…. I would have done anything out of love for them, but I would never have considered euthanasia.”

But this moving anecdote is no argument against the Belgian law. Indeed, under that law the mother’s refusal of euthanasia would be decisive. It is one thing for a parent to say that I do not believe that euthanasia is in my child’s best interests; it is quite another to say that any parent who thinks euthanasia is in their child’s best interests must be wrong.

To understand a moral position it is useful to state the moral principles and the empirical assumptions on which it is based. So I will state mine.

Moral Principles

- A mercy killing can be in a person’s best interests.

- A person’s competent wishes should have very great weight in what is done to her.

- Parents’ views as to what it right for their children should normally be given significant moral weight.

- Mercy killing, in the situation where a person is suffering and faces a short life anyway, and where the person is requesting it, can be the right thing to do.

Empirical assumptions

- There are some situations in which children with a terminal illness suffer so much that it is in their interests to be dead.

- There are some situations in which the child’s suffering cannot be sufficiently alleviated short of keeping the child permanently unconscious.

- A law can be formulated with sufficient safeguards to prevent euthansia from being carried out in situations when it is not justified.

This last empirical claim is the most difficult to assess. Opponents of child euthanasia may believe such safeguards are not possible: that it is better not to risk sliding down the slippery slope. But the ‘slippery slope argument’ is morally problematic: it is an argument against doing the right thing on some occasions (carrying out a mercy killing when that is right) because of the danger of doing the wrong thing on other occasions (carrying out a killing when that is wrong). I prefer to focus on safeguards against slipping. But empirical evidence could lead me to change my views on child euthanasia. My guess is that for many people who are against the new Belgian law, it is the fear of the slippery slope that is ultimately crucial. Much moral disagreement, when carefully considered, comes down to disagreement over facts. Scientific evidence is a key component of moral argument.

Tony Hope is Emeritus Professor of Medical Ethics at the University of Oxford and the author of Medical Ethics: A Very Short Introduction.

The Very Short Introductions (VSI) series combines a small format with authoritative analysis and big ideas for hundreds of topic areas. Written by our expert authors, these books can change the way you think about the things that interest you and are the perfect introduction to subjects you previously knew nothing about. Grow your knowledge with OUPblog and the VSI series every Friday, subscribe to Very Short Introductions articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS, and like Very Short Introductions on Facebook.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only science and medicine articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Image credit: Legality of Euthanasia throughout the world By Jrockley. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons

The post Morality, science, and Belgium’s child euthanasia law appeared first on OUPblog.

Yesterday, I was flipping through my (very heavy) copy of The Oxford Companion to American Food and Drink, and I found…

…wait for it…

…wait for it…

an entry on BOOYAH! What is booyah? I’m glad you asked.

BOOYAH is a thick mixed stew that demonstrates how American ethnic food can include dishes that would be completely alien in recipe or usage to past generations. Groups of Belgian American Walloons settled around Door County (Green Bay), Wisconsin, in the 1850s, bringing with them a dish of clear bouillon served with rice. The hen of that had been boiled to obtain the bouillon made another meal the next day. Sometime in the 1930s, men took over the dish and turned it into a thick soup full of boned chicken meat and vegetables (and often served with saltines) at the annual Belgian American kermis harvest festival. The pots became larger, the men used a canoe paddle to stir the soup, and “booyah” became the name of the event as well as the central dish.

By the 1980s, booyah was served at church fund-raisers, at a midsummer ethnic festival for visitors, and on Green Bay Packer football weekends. Secret recipes and “booyah kings” have been added to make booyah male-bonding ritual like those surrounding barbecue, chili con carne, burgoo, and Brunswick stew – the latter two soup-stews being highly similar to booyah.

It is possible that booyah has features of other Belgian soups, such as hochepot. It often happens that American ethnic dishes begin to accumulate features of several old-country dishes. It also may be that booyah is not descended from Belgian bouillon at all. Around Saint Cloud, Minnesota, Polish Americans believe that “bouja” is an old Polish soup, and men make it as much as Belgian Americans do in Door County, Wisconsin, but flavored with pickling spices. An early published recipe (1940) describes “boolyaw” as a French Canadian dish from the hunting camps of Michigan. A more recent Wisconsin cookbook called it an old German recipe. The dish has gone from a thin soup made by women at home to a thick stew made by men for communal events. An Italian American might mistake booyah for minestrone, yet Belgian Americans in Wisconsin believe it is named for Godfrey of Bouillon, a leader of the First Crusade. The fruit tarts served for desert at booyah feasts are made by women as much as they were in Eastern Belgium in the early nineteenth century.

Mark H. Zanger, author of The American History Cookbook