By Tony Hope

Science and morality are often seen as poles apart. Doesn’t science deal with facts, and morality with, well, opinions? Isn’t science about empirical evidence, and morality about philosophy? In my view this is wrong. Science and morality are neighbours. Both are rational enterprises. Both require a combination of conceptual analysis, and empirical evidence. Many, perhaps most moral disagreements hinge on disagreements over evidence and facts, rather than disagreements over moral principle.

Consider the recent child euthanasia law in Belgium that allows a child to be killed – as a mercy killing – if: (a) the child has a serious and incurable condition with death expected to occur within a brief period; (b) the child is experiencing constant and unbearable suffering; (c) the child requests the euthanasia and has the capacity of discernment – the capacity to understand what he or she is requesting; and, (d) the parents agree to the child’s request for euthanasia. The law excludes children with psychiatric disorders. No one other than the child can make the request.

Is this law immoral? Thought experiments can be useful in testing moral principles. These are like the carefully controlled experiments that have been so useful in science. A lorry driver is trapped in the cab. The lorry is on fire. The driver is on the verge of being burned to death. His life cannot be saved. You are standing by. You have a gun and are an excellent shot and know where to shoot to kill instantaneously. The bullet will be able to penetrate the cab window. The driver begs you to shoot him to avoid a horribly painful death.

Would it be right to carry out the mercy killing? Setting aside legal considerations, I believe that it would be. It seems wrong to allow the driver to suffer horribly for the sake of preserving a moral ideal against killing.

Thought experiments are often criticised for being unrealistic. But this can be a strength. The point of the experiment is to test a principle, and the ways in which it is unrealistic can help identify the factual aspects that are morally relevant. If you and I agree that it would be right to kill the lorry driver then any disagreement over the Belgian law cannot be because of a fundamental disagreement over mercy killing. It is likely to be a disagreement over empirical facts or about how facts integrate with moral principles.

There is a lot of discussion of the Belgian law on the internet. Most of it against. What are the arguments?

Some allow rhetoric to ride roughshod over reason. Take this, for example: “I’m sure the Belgian parliament would agree that minors should not have access to alcohol, should not have access to pornography, should not have access to tobacco, but yet minors for some reason they feel should have access to three grams of phenobarbitone in their veins – it just doesn’t make sense.”

But alcohol, pornography and tobacco are all considered to be against the best interests of children. There is, however, a very significant reason for the ‘three grams of phenobarbitone’: it prevents unnecessary suffering for a dying child. There may be good arguments against euthanasia but using unexamined and poor analogies is just sloppy thinking.

I have more sympathy for personal experience. A mother of two terminally ill daughters wrote in the Catholic Herald: “Through all of their suffering and pain the girls continued to love life and to make the most of it…. I would have done anything out of love for them, but I would never have considered euthanasia.”

But this moving anecdote is no argument against the Belgian law. Indeed, under that law the mother’s refusal of euthanasia would be decisive. It is one thing for a parent to say that I do not believe that euthanasia is in my child’s best interests; it is quite another to say that any parent who thinks euthanasia is in their child’s best interests must be wrong.

To understand a moral position it is useful to state the moral principles and the empirical assumptions on which it is based. So I will state mine.

Moral Principles

- A mercy killing can be in a person’s best interests.

- A person’s competent wishes should have very great weight in what is done to her.

- Parents’ views as to what it right for their children should normally be given significant moral weight.

- Mercy killing, in the situation where a person is suffering and faces a short life anyway, and where the person is requesting it, can be the right thing to do.

Empirical assumptions

- There are some situations in which children with a terminal illness suffer so much that it is in their interests to be dead.

- There are some situations in which the child’s suffering cannot be sufficiently alleviated short of keeping the child permanently unconscious.

- A law can be formulated with sufficient safeguards to prevent euthansia from being carried out in situations when it is not justified.

This last empirical claim is the most difficult to assess. Opponents of child euthanasia may believe such safeguards are not possible: that it is better not to risk sliding down the slippery slope. But the ‘slippery slope argument’ is morally problematic: it is an argument against doing the right thing on some occasions (carrying out a mercy killing when that is right) because of the danger of doing the wrong thing on other occasions (carrying out a killing when that is wrong). I prefer to focus on safeguards against slipping. But empirical evidence could lead me to change my views on child euthanasia. My guess is that for many people who are against the new Belgian law, it is the fear of the slippery slope that is ultimately crucial. Much moral disagreement, when carefully considered, comes down to disagreement over facts. Scientific evidence is a key component of moral argument.

Tony Hope is Emeritus Professor of Medical Ethics at the University of Oxford and the author of Medical Ethics: A Very Short Introduction.

The Very Short Introductions (VSI) series combines a small format with authoritative analysis and big ideas for hundreds of topic areas. Written by our expert authors, these books can change the way you think about the things that interest you and are the perfect introduction to subjects you previously knew nothing about. Grow your knowledge with OUPblog and the VSI series every Friday, subscribe to Very Short Introductions articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS, and like Very Short Introductions on Facebook.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only science and medicine articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

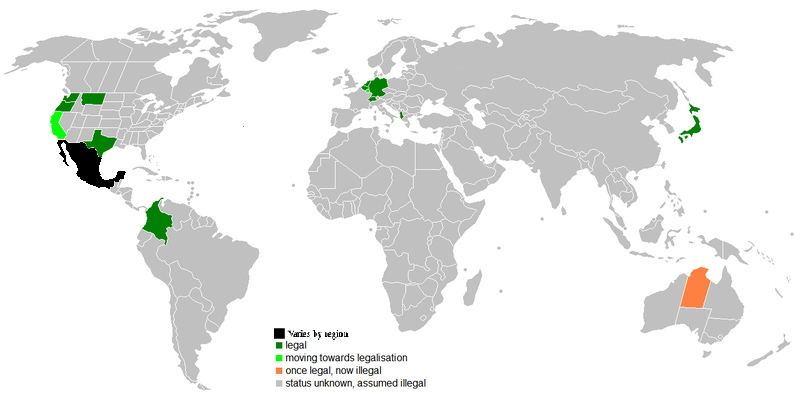

Image credit: Legality of Euthanasia throughout the world By Jrockley. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons

The post Morality, science, and Belgium’s child euthanasia law appeared first on OUPblog.

By Lori Gruen

The decision by the administrators of the Copenhagen Zoo to kill a two-year-old giraffe named Marius by shooting him in the head in February 2014, then autopsy his body in public and feed Marius’ body parts to the lions held captive at the zoo created quite an uproar. When the same zoo then killed the lions (an adult pair and their two cubs) a month later to make room for a more genetically-worthy captive, the uproar became more ferocious.

Animal lovers across the globe were shocked and sickened by these killings and couldn’t understand why this bloodshed was being carried out at a zoo.

The zoo’s justification for killing Marius was that he had genes that were already “well represented” in the captive giraffe population in Europe. The justification for killing the lions was that the zoo was planning to introduce a younger male who was not genetically related to any of the females in the group.

Sacrificing the well-being and even the lives of individual animals in the name of conserving a diverse gene pool is commonplace in zoos. Euthanasia, usually by means less grotesque than a shotgun to the head, is quite common in European zoos. In US zoos, contraception is often used to prevent “over-representation” of certain gene lines. The European zoos’ reason for not using birth control the way most American zoos do is that they believe allowing animals to reproduce provides the animals with the opportunity to engage the fuller range of species typical behaviors, but that also means killing the undesirable offspring. In both European and US zoos, families are broken up and individuals are shipped to other facilities to diversify and manage the captive gene pool.

If this all has a ring of eugenic reasoning, consider what the executive director of the World Association of Zoos and Aquariums, Gerald Dick, had to say: “In Europe, there is a strict attempt to maintain genetically pure animals and not waste space in a zoo for genetically useless specimens.”

A stuffed giraffe, representing Marius, at a protest against zoos and the confinement of animals in Lisbon, 2014

The high-profile slaughter of Marius and the lions that ate his body focus attention on an important debate about the purpose of zoos and more generally the ethics of captivity. Originally, zoos were designed to amuse, amaze, and entertain visitors. As public awareness of the plight of endangered species and their diminishing habitats grew, zoos increasingly saw their roles as conservation and education. But just what is being conserved and what are the educational lessons that zoo-goers take away from their experiences at the zoo?

A recent study suggests that zoo-goers learn about biodiversity by visiting zoos. Critics have suggested that the study is not particularly convincing in linking the small increase in understanding of biodiversity with the complex demands of conservation. Some zoos are committed to direct conservation efforts; the Wildlife Conservation Society (aka the Bronx Zoo) and the Lincoln Park Zoo are just two examples of zoos that have extensive and successful conservation programs. Despite these laudable programs, these WAZA-accredited zoos, like the European zoos, are also in the business of gene management and a central tenet of the current management ethos is to value genetic diversity over individual well-being.

Awe-inspiring animals such as giraffes and gorillas and cheetahs and chimpanzees are not seen as individuals, with distinct perspectives, when viewed, as Dick says, as either useful or useless “specimens.” They are valued, if at all, as representative carriers of their species’ genes.

This distorts our understanding of other animals and our relationships to them. Part of the problem is that zoos are not places in which animals can be seen as dignified. Zoos are designed to satisfy human interests and desires, even though they largely fail at this. A trip to the zoo creates a relationship in which the observer, often a child, has a feeling of dominant distance over the animals being looked at. It is hard to respect and admire a being that is captive in every respect and viewed as a disposable specimen, one who can be killed to satisfy a mission that is hard for the zoo-going public to fully understand, let alone endorse.

Causing death is what zoos do. It is not all that they do, but it is a big part of what happens at zoos, even if this is usually hidden from the public. Zoos are institutions that not only purposely kill animals, they are also places that in holding certain animals captive, shorten their lives. Some animals, such as elephants and orca whales, cannot thrive in captivity and holding them in zoos and aquaria causes them to die prematurely.

Death is a natural part of life, and perhaps we would do well to have a less fearful, more accepting attitude about death. But those who purposefully bring about premature death run the risk of perpetuating the notion that some lives are disposable. It is that very idea that we can use and dispose of other animals as we please that has led to the problems that have zoos and others thinking about conservation in the first place. When institutions of captivity promote the idea that some animals are disposable by killing “genetically useless specimens” like young Marius and the lions, they may very well be undermining the tenuous conservation claims that are meant to justify their existence.

Lori Gruen is Professor of Philosophy, Feminist, Gender, and Sexuality Studies, and Environmental Studies at Wesleyan University where she also coordinates Wesleyan Animal Studies and directs the Ethics in Society Project. She is the author of The Ethics of Captivity.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only philosophy articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Image credit: Sit-in protest in Lisbon. Photo by Mattia Luigi Nappi, 2014. CC-BY-SA-3.0 via Wikimedia Commons

The post Disposable captives appeared first on OUPblog.

Baroness Mary Warnock is a philosopher renowned for her writing on moral issues. Previously a Fellow and Tutor in Philosophy at St Hugh’s College, Oxford, and Mistress of Girton College, Cambridge, she is now an Independent Life Peer in the House of Lords, and a writer and broadcaster. Elisabeth Macdonald has spent her career working in cancer medicine in the UK as well as periods as a Consultant Oncologist in France and in research at Stanford University, California. Their book, Easeful Death: Is There a Case for Assisted Dying?, is publishing in paperback in March, and you can read their previous blog post here. The following is an excerpt about the medical perspective of assisted death.

Doctors in general are of a conservative turn of mind when contemplating decisions involving their patients. Medicine is a discipline in which taking risks with patient welfare is almost never justified and doctors, even those trained to model their care on the latest evidence-based research, are not easily persuaded to change a long established policy. It is not surprising that the contemplation of such profoundly serious changes of practice as assisted suicide and euthanasia has led to controversy, disagreement, and fierce professional debate. Doctors are currently forbidden, like every other citizen, to end human life. There is no legal indulgence conferred by a medical or nursing qualification.

So what attitudes do these professionals express when discussing the interests of patients in grave distress who seek medical aid to end their lives? In medical ethics much discussion centres on the difference between ‘killing’ and ‘letting die’. For many people it seems important to distinguish between killing and letting die and to prohibit the former while authorizing the latter in certain cases. In the past the distinction was sometimes, not very helpfully, referred to as that between ‘active’ and ‘passive’ euthanasia. In recent years, however, the distinction between killing and letting die has become blurred. For example, switching off a respiratory-support machine could be interpreted as actively terminating a patient’s life. Alternatively this act may be seen as withdrawing the artificial means maintaining a life which is already unsustainable by the individual alone. In other words this act discontinues an artificial circulation in a patient who is actually already dead (letting die).

grave distress who seek medical aid to end their lives? In medical ethics much discussion centres on the difference between ‘killing’ and ‘letting die’. For many people it seems important to distinguish between killing and letting die and to prohibit the former while authorizing the latter in certain cases. In the past the distinction was sometimes, not very helpfully, referred to as that between ‘active’ and ‘passive’ euthanasia. In recent years, however, the distinction between killing and letting die has become blurred. For example, switching off a respiratory-support machine could be interpreted as actively terminating a patient’s life. Alternatively this act may be seen as withdrawing the artificial means maintaining a life which is already unsustainable by the individual alone. In other words this act discontinues an artificial circulation in a patient who is actually already dead (letting die).

We would contend that there is no morally relevant difference between killing someone and allowing him to die. A well-known example cited in medical ethics describes two young men, each of whom want their 6-year-old cousin to die in order that they can gain a large inheritance. Smith drowns his cousin while the boy is taking a bath. Jones plans to drown his cousin, but as he enters the bathroom he sees the boy slip and hit his head: Jones stands by doing nothing while the boy drowns.

Smith killed his cousin: Jones merely allowed his cousin to die. Both of these acts are clearly reprehensible but do demonstrate that the distinction between killing and letting die is morally irrelevant. Moreover, someone who starves another person to death is as guilty of murder as someone who poisons that person. The person who allows a fellow human being to die of hunger is as morally guilty as someone who acts to poison him. The difference lies in the more obvious and direct causal implications of the verb ‘to kill’. Killing, like pushing or pulling, kicking or smashing, is manifestly doing something to produce a certain effect. John Stuart Mill insisted that a cause is not necessarily an ‘active intervention’. The failure of the guards to patrol the walls may cause the fall of the city. Yet people may still instinctively feel that failing to do something is less causal than killing them. It is less ‘hands on’. It is after all doing nothing, and may therefore seem to be incapable of producing any effect. Ex nihilo nihil fit. Moreover, ‘to kill’ is a verb that contains a record of its own success. If I kill you, you are dead; whereas if I, say, fail to feed you, there is room for another event to come along either to save or to dispatch you. There is space for what the lawyers call novus actus interveniens.

A case that illustrates the medical abhorrence of active intervention to bring about death was that of a 40-year-old woman known only as Ms B. In 2001 she suffered a burst blood vessel in her neck and became totally paralysed. She was kept alive on a ventilator for a year, her brain unaffected. When the year was up, she asked that she might get someone to switch off the ventilator at a time of her choice, when she felt she had had enough. The hospital authorities refused, and one of the doctors involved was reported as saying: ‘She is asking us to kill her, and this we would not like to do’. Ms B appealed to the courts, and a court was convened round her bed. The judge, Lady Butler-Sloss found that she was suffering from no mental incapacity, and that it would be lawful for the hospital to grant her request. They still repeated that they could not kill her, even if it would be a lawful act. So Ms B was moved to another, less squeamish hospital, where in due course she asked for the ventilator to be switched off and she died.

Thus, doctors are profoundly suspicious of any action which may be classified as killing; and this is partly, we believe, because of the emotive violence contained within the very word ‘killing’. This word carries with it images of battlefields or grisly car accidents. These images are far removed from the scene of calm, caring, easeful, and timely death that is the ideal we would all wish eventually for ourselves.