new posts in all blogs

Viewing: Blog Posts Tagged with: Law &, Most Recent at Top [Help]

Results 26 - 50 of 143

How to use this Page

You are viewing the most recent posts tagged with the words: Law & in the JacketFlap blog reader. What is a tag? Think of a tag as a keyword or category label. Tags can both help you find posts on JacketFlap.com as well as provide an easy way for you to "remember" and classify posts for later recall. Try adding a tag yourself by clicking "Add a tag" below a post's header. Scroll down through the list of Recent Posts in the left column and click on a post title that sounds interesting. You can view all posts from a specific blog by clicking the Blog name in the right column, or you can click a 'More Posts from this Blog' link in any individual post.

By: AlanaP,

on 1/14/2013

Blog:

OUPblog

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

Law,

Current Affairs,

spy,

Soviet,

*Featured,

Law & Politics,

fourth amendment,

Constance Jordan,

Judith Coplon,

Learned Hand,

Reason and Imagination,

Sixth Amendment,

coplon,

mckeon,

accused,

judith,

hand’s,

district,

nkgb,

gubitchev,

Add a tag

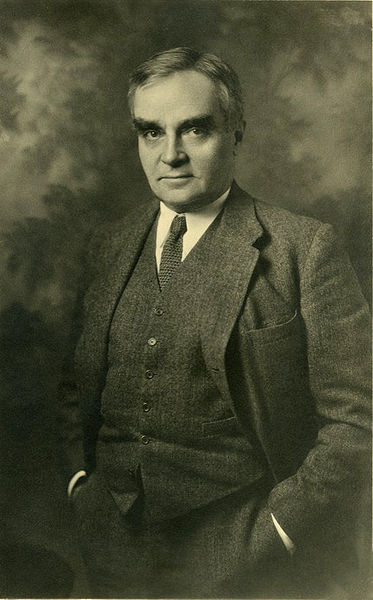

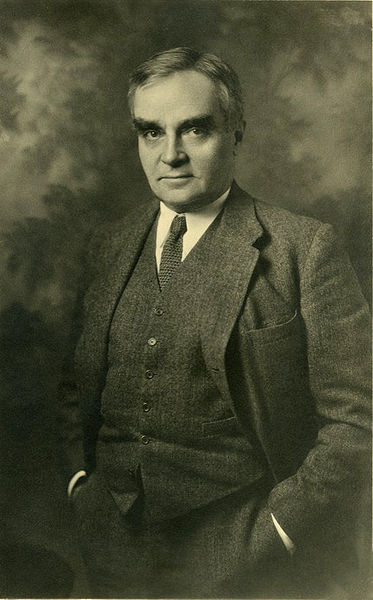

Learned Hand (1872-1961) served on the United States District Court and is commonly thought to be the most influential justice never to serve on the Supreme Court. He corresponded with people in different walks of life, some who were among his friends and acquaintances, others who were strangers to him. In the letter below, Hand writes to Mary McKeon, a New Yorker troubled by Hand’s decision to invalidate the warrantless search and consequent arrest of the Soviet spy, Judith Coplon.

To Mary McKeon

December 28, 1950

Dear Miss McKeon:

I have your letter about the Coplon case and I can understand why you are troubled about the result; and because you were not abusive, I am going to try to explain it to you.

It is a rule — well settled by the decisions of the Supreme Court — that evidence which the Government secures by its own violation of law it may not use against the person whose rights have been invaded. An extreme example of this would be in case a United States marshal were to break into the house of an accused person and seize his papers; the Government would not be allowed to use the papers against the person whose house had been entered. The same thing is true of documents found upon the person of one who is unlawfully arrested as was Judith Coplon. That was one ground for the reversal. The other was that during the trial it became necessary for the Government to depend upon evidence which it was unwilling to let her see. The Constitution provides that a person accused of crime is entitled to have all witnesses, who are called against him, brought into court at the trial.

Thus in these two instances the rights of the accused were violated, which is entirely consistent with her guilt. Perhaps, if you reflect, you will agree that it is not desirable to convict people, even though guilty, if to do so it is necessary to violate those rules on which the liberty of all of us depends.

Truly yours,

Learned Hand

The letter above was excerpted from Reason and Imagination: The Selected Letters of Learned Hand, edited by Constance Jordan, a retired professor of comparative literature and also Hand’s granddaughter. In 1944, Coplon, who worked for the Foreign Agents Registration section, was recruited as a spy by the NKGB, i.e., the People’s Commissariat for State Security. In 1949, FBI agents detained Coplon as she met with Valentin Gubitchev, a KGB official employed by the United Nations, while carrying what she thought were secret U.S. government documents; in actuality, they were fakes, planted in her purse at the order of J. Edgar Hoover. Declared guilty of espionage by the United States District Court for the Southern District of New York in 1949, Coplon appealed to the United States Court of Appeals for the Second Circuit. In United States v. Coplon, in an opinion authored by Hand and announced on December 5th, her conviction was overturned.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only law articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Image credit: Judge Learned Hand circa 1910. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

The post A letter from Learned Hand appeared first on OUPblog.

By: Kirsty,

on 1/14/2013

Blog:

OUPblog

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

bryan fanning,

community development journal,

community participation,

denis dillon,

haringey,

tottenham riots,

councillors,

alan stanton,

Sociology,

london,

Current Affairs,

riots,

regeneration,

Social Sciences,

*Featured,

big society,

Law & Politics,

oxford journals,

tottenham,

Add a tag

By Bryan Fanning and Denis Dillon

The Tottenham riots in the London Borough of Haringey took place in August 2011. We examined three responses to them: reports by North London Citizens, an alliance of 40 mostly faith community institutions including schools, the Tottenham Community Panel established by Haringey Council, and the Riots, Communities and Victims Panel established by Parliament.

The riots coincided with the end of an era of British urban policy when various community-centred regeneration programmes introduced by the previous New Labour Government, were being wound down. One of its flagship initiatives was the New Deal for Communities (NDC), a ten year programme which invested £50 million in each of thirty deprived areas including Tottenham. More recently, David Cameron has promoted the idea of the Big Society with an accompanying rhetoric that blames big government for enfeebling the civic sphere.

Two of the three analyses of the Tottenham riots that we examined shared this perspective. North London Citizens emphasised the need to create new community leaders; the Riots Communities and Victims Panel emphasised an on-going failure of services to engage with communities and vaguely endorses an agenda of neighbourhood-level community empowerment. Cameron’s Big Society agenda envisioned communities and neighbourhoods becoming empowered to take local decisions and solve local problems taking over the running of services and facilities where appropriate. None of the three reports make such recommendations for Tottenham. Rather, they restate in minor key the need for greater responsiveness to communities with no clear ideas about how this might be achieved.

Two of the three analyses of the Tottenham riots that we examined shared this perspective. North London Citizens emphasised the need to create new community leaders; the Riots Communities and Victims Panel emphasised an on-going failure of services to engage with communities and vaguely endorses an agenda of neighbourhood-level community empowerment. Cameron’s Big Society agenda envisioned communities and neighbourhoods becoming empowered to take local decisions and solve local problems taking over the running of services and facilities where appropriate. None of the three reports make such recommendations for Tottenham. Rather, they restate in minor key the need for greater responsiveness to communities with no clear ideas about how this might be achieved.

All three reports emphasised a deficit in community cohesion. All three identified inadequate engagement by local service providers with residents as part of the problem. But Tottenham has been here before. The aftermath of the 1985 riot saw considerable effort to improve, foster and build community cohesion in Tottenham. Many of the buildings that were looted and burned in 2011 had been the focus of regeneration efforts.

We had just completed research on the efficacy of such policies when the riots occurred. Our 2011 book Lessons for the Big Society: planning, regeneration and the politics of community participation (Ashgate, 2011) examined a long history of failed efforts by the local authority to secure such participation. There were many reasons for this. Labour held a political monopoly in Tottenham. Community activism not sponsored by the party was often ignored. The institutional culture of the local authority councillors and officials was often hostile to community participation in decision-making even if official rhetoric claimed otherwise. Well-to-do parts of the borough had articulate well-organised groups capable of putting pressure on officials and councillors. Community groups in Tottenham lacked the skills and cultural capital that worked to win responsiveness from institutional actors.

The kind of community capacity that regeneration programmes in Tottenham sought to introduce appeared feeble compared to the on-going capacity for unsolicited activism found in well-to-do areas – expressed through single issue campaigns, the establishment of long-standing amenity groups and well-organised networks able to compel responsiveness from Council officials and councillors. The New Labour diagnosis was that areas like Tottenham lacked the necessary social capital. But the regeneration programmes it put in place engendered only a limited form of community capacity, and this depended on the life-support of funding that has since ended.

What then for Cameron’s Big Society? Even after decades of community-focused urban renewal in Tottenham, both community-institutional relationships and community cohesion remain weak. However, this does not justify the withdrawal of state support or bucolic expectations that civil society can fill the resulting void with minimal support. The very localities that need community empowerment also need state support the most.

We argue that what might work for Tottenham is an approach that seriously interrogates why past regeneration efforts were unable to empower local communities but at the same time accepts that such empowerment cannot be realised without significant state funding. It would take seriously the scepticism-bordering-on-hostility of the Big Society to local authority officialdom. But what Tottenham needs for the foreseeable future is big government willing to learn from past mistakes.

Professor Bryan Fanning is the Head of the School of Applied Social Science at University College Dublin. Dr Denis Dillon is employed by Community Services Volunteers (CSV) in North London. They are the co-authors of Lessons for the Big Society: planning, regeneration and the politics of community participation (Ashgate, 2011). Their article, The Tottenham riots: the Big Society and the recurring neglect of community participation, appears in Community Development Journal.

Since 1966 the leading international journal in its field, Community Development Journal covers a wide range of topics, reviewing significant developments and providing a forum for cutting-edge debates about theory and practice. It adopts a broad definition of community development to include policy, planning and action as they impact on the life of communities. It publishes critically focused articles which challenge received wisdom, report and discuss innovative practices, and relate issues of community development to questions of social justice, diversity and environmental sustainability.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only current affairs articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Image credit: After the Riot – View from near Scotland Green. Photo by Alan Stanton, 2011. Creative Commons Licence. (via Wikimedia Commons)

The post The Tottenham riots, the Big Society, and the recurring neglect of community participation appeared first on OUPblog.

By: Nicola,

on 1/2/2013

Blog:

OUPblog

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

Economics,

Law,

Constitution,

business,

Current Affairs,

policy,

globalization,

Governance,

oecd,

*Featured,

Law & Politics,

Business & Economics,

constitutionalization,

grahame thompson,

quasi-consitutionalization,

the constitutionalization of the global corporate sphere,

quasi,

rbls,

Add a tag

By Grahame Thompson

Have we seen a potentially new form of global governance quietly emerging over the last decade or so, one that is establishing a surrogate and informal process of the constitutionalization of global economic and political relationships, something that is creeping up on us almost unnoticed? This issue of ‘global constitutionalization’ has become an important topic of analysis over recent years. Its development is most obvious in the case of business and corporate activity but I suggest it has a much wider provenance and is threatening to encompass many other aspects of global governance like human rights, security and warfare, environmental regulation, and more besides. One difficulty in analyzing this trend is to define its characteristics and parameters since it represents a rather loose configuration, one that is not easy to pin down.

Quasi-constitutionalization is a surrogate process of constitutionalization, not a coherent program with a rounded set of outcomes but full of contradictory half-finished currents and projects: an ‘assemblage’ of many disparate advances and often directionless moves – almost an accidental coming together of elements. So it does not amount to a ‘system’ in any conventional sense. This means it marshals together a complex bricolage of resources: material techniques and devices like models, documents, court decisions, legal statutes and treaties; institutional orders like legal apparatuses, bodies and governance organizations; and discursive expertise, theoretical knowledges and instruments. But it is a process nonetheless: it is building norms of conduct, rule-making, and a distribution of powers in a ‘global polity’.

Quasi-constitutionalization is a surrogate process of constitutionalization, not a coherent program with a rounded set of outcomes but full of contradictory half-finished currents and projects: an ‘assemblage’ of many disparate advances and often directionless moves – almost an accidental coming together of elements. So it does not amount to a ‘system’ in any conventional sense. This means it marshals together a complex bricolage of resources: material techniques and devices like models, documents, court decisions, legal statutes and treaties; institutional orders like legal apparatuses, bodies and governance organizations; and discursive expertise, theoretical knowledges and instruments. But it is a process nonetheless: it is building norms of conduct, rule-making, and a distribution of powers in a ‘global polity’.

I call this a quasi-constitutional process because while it resembles a constitution in many respects it is difficult to transpose constitutionality directly into an international environment where there is no single competent authority that might foster or enforce such a constitution.

In turn, this connects to various senses of the juridicalization of international corporate and other affairs, where new or revitalized types of law are increasingly being brought into play as the mechanisms for resolving disputes or organizing governance. This involves new forms of public law, private law, customary law, regulatory and administrative law, all of which are rapidly evolving in the international arena alongside traditional international law. Institutions that embody such a process are the WTO, various agencies of the UN, the OECD, Bilateral Trade and Investment treaties, and a huge number of standard setting and benchmarking organization many of which are private in character but which both claim and exercise a public power at the global level. This is the site of a reinvigorated private law and private authority operating in the international domain. In the case of companies, they are increasingly adopting the language of global corporate citizenship to characterize their activity as civic actors in this evolving quasi-constitutional environment, and they are being addressed as such by bodies like the World Economic Forum and the UN’s Global Compact. Bilateral trade and investment treaties have mushroomed over recent years. Investment treaties are an example of global private administrative law in action.

On the other hand we have the OECD in its capacity as sponsor of socially responsible conduct by multinational companies (Guidelines for Multinational Enterprises) which has become an instrument of global public administrative law. John Ruggie’s recent attempt to introduce a comprehensive regime of human rights into the business world (the UNs Protect, Respect and Remedy Framework) is another case in point of the creeping quasi-constitutionalizing process.

But a major issue of concern is whether quasi-constitutionalization leads to the Rule by Laws (RbLs) rather than the Rule of Law (RoL) in the international system? The RoL may be being given away as RbLs replace a comprehensive system of democratically constituted judicial review, which cannot happen in the case of global quasi-constitutionality.

Thus in this evolving environment, instead of the rule by elected and accountable political officials we are seeing the emergence of rule by lawyers and by aged judges and law professors in international commercial and other matters. These are the actors that are leading the process of institutional rule-making. Public and particularly private elites are making-up the rules as they go along, arbitrarily and on an ad hoc basis. I call this a rule by a new self-appointed Guild of Lawyers on the one hand and a new Clerisy of the Law on the other. In effect, we are giving up any form of democratic legitimacy and accountability with this introduction of global quasi-constitutionalization.

Grahame F. Thompson is Professor of Political Economy at the Copenhagen Business School (Denmark), and Emeritus Professor at the Open University (England). His research and teaching interests have been in international political economy matters, and globalization; with a recent focus on the role of business organization in the context of international economic matters. He is the author of The Constitutionalization of the Global Corporate Sphere? (OUP, 2012).

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only articles on law and politics on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only business and economics articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Image credit: Cover of U.S. Constitution by giftlegacy via iStockphoto.

The post Should we be worried about global quasi-constitutionalization? appeared first on OUPblog.

By: Elvin Lim,

on 12/20/2012

Blog:

OUPblog

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

Newtown,

errant,

vigilance,

tyrannical,

anachronistic,

mourning,

Current Affairs,

MSNBC,

Fox News,

amendment,

NRA,

President Barack Obama,

gun control,

Second Amendment,

Anti-Federalists,

Federalists,

shootings,

Elvin Lim,

anti-intellectual presidency,

*Featured,

Law & Politics,

Add a tag

By Elvin Lim

The tragic shootings in Newtown, CT, have plunged the nation into the foundational debate of American politics.

Over at Fox News, the focus as been on mourning and the tragedy of what happened. As far as the search for solutions go, the focus has been on how to cope, what to say to children, and what to do about better mental health screening. It is consistent with the conservative view that when bad things happen, they happen because of errant individuals, not flawed societies. The focus on mourning indicates the view that when bad things happen, they are the inevitable costs of liberty.

At MSNBC, the focus has been on tragedy as a wake up call, not a thing in itself to simply mourn; on finding legislative and governmental solutions — gun control. This is consistent with the liberal view that when bad things happen, they happen because of flawed societies, not just the result of errant individuals or evil as an abstract entity.

The question of which side is right is an imponderable. Conservatives believe that in the end, our vigilance against tyrannical government is our first civic duty. This was the logic behind the Second Amendment. It comes from a long line of Radical Whig thinking that the Anti-Federalists inherited. That is why Second Amendment purists can reasonably argue that that citizens should continue to have access to (even) semi-automatic guns. They will say that the Second Amendment is not just for hunting; it is for liberty against national armies. Liberals, on the other hand, believe that a government duly constituted by the people need not fear government; and it is citizen-on-citizen violence that we ought to try to prevent. This line of thinking began with Hobbes, who had theorized that we lay down our arms against each other, so that one amongst us alone wields the sword. Later, we called this sovereign the state. The Federalists leaned in this tradition.

Should we fear government more or fellow citizens who have access to guns? Should government or citizens enjoy the presumption of virtue? Who knows. There is no answer on earth that would permanently satisfy both political sides in America, because conservatives believe that most citizens, most of the time, are virtuous, and there is no need to take a legislative sledgehammer to restrict the liberty of a few errant individuals at the expense of everybody else. Liberals, conversely, believe that government and regulatory activity are virtuous and necessary most of the time, and there is little practical cost to most citizens to restrict a liberty (to bear arms) that is rarely, if ever, invoked. Put another way: conservatives focus on the vertical dimension of tyranny; liberals fear most the horizontal effects of mutual self-destruction.

What is a president to do? It depends on which side of the debate he stands. Barack Obama believes that the danger we pose to ourselves exceeds the danger of tyrannical government (for which a right to bear arms was originally codified). The winds of public opinion may be swaying in his direction, and Obama appeared to be ready to mould it when he asked: “Are we really prepared to say that we are powerless in the face of such carnage?”

Here is one neo-Federalist argument that Obama can use, should he take on modern Anti-Federalists. If the Constitution truly were of the people, then it is self-contradictory to speak of vigilance against it. In other words, the Second Amendment is anachronistic. It was written in an era of monarchy, as a bulwark against Kings. To those who claim to be constitutional conservatives, Obama may reasonably ask: either the federal government is not sanctioned by We the People, and therefore we must forever be jealous of it; or, the federal government represents the People and we need not treat it as a distant potentate and overstate our fear of it.

If this is to be the age of renewed faith in government, as it appears to be Obama’s mission, then the President will be more likely to convince Americans to lay down our arms; he will persuade us that our vigilance against government by the people is counter-prouctive and anachronistic. But, to move “forward,” he must first convince the NRA and its ideological compatriots that we can trust our government. Only the greatest of American presidents have succeeded in this most herculean of tasks, for our attachment to the spirit of ’76 cannot be understated.

Elvin Lim is Associate Professor of Government at Wesleyan University and author of The Anti-Intellectual Presidency, which draws on interviews with more than 40 presidential speechwriters to investigate this relentless qualitative decline, over the course of 200 years, in our presidents’ ability to communicate with the public. He also blogs at www.elvinlim.com and his column on politics appears on the OUPblog regularly.

Elvin Lim is Associate Professor of Government at Wesleyan University and author of The Anti-Intellectual Presidency, which draws on interviews with more than 40 presidential speechwriters to investigate this relentless qualitative decline, over the course of 200 years, in our presidents’ ability to communicate with the public. He also blogs at www.elvinlim.com and his column on politics appears on the OUPblog regularly.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only politics and law articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

The post On the Second Amendment: should we fear government or ourselves? appeared first on OUPblog.

By: Alice,

on 12/19/2012

Blog:

OUPblog

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

billionaire,

Edward Zelinsky,

Warren Buffett,

estate,

*Featured,

giving pledge,

charitable,

buffett,

taxation,

Law & Politics,

Business & Economics,

charitable contributions,

Abigail Disney,

estate tax charitable deduction,

federal estate and gift taxes,

fiscal cliff,

Responsible Wealth,

Richard Rockefeller,

deduction,

bequest,

philanthropy,

Current Affairs,

bill gates,

deductible,

Add a tag

By Edward Zelinsky

One widely-discussed possibility for reforming the federal income tax is limiting the deduction for charitable contributions. Whether or not Congress amends the Code to restrict the income tax deduction for charitable contributions, Congress should limit the charitable contribution deduction under the federal estate and gift taxes. Such a limit would balance the need for federal revenues with the desirability of encouraging charitable giving.

On December 11th, the advocacy group Responsible Wealth called for the federal government to tax estates over $4,000,000 at rates starting at 45%. Among those joining this call were heirs to old fortunes such as Abigail Disney and Richard Rockefeller and owners of new wealth such as Bill Gates, Sr. Most notably, Warren Buffett agreed (as he has in the past) with this recent plea for higher estate taxes.

I am a fan of my fellow Nebraskan and agree with him that the federal government should impose estate taxes, particularly on large fortunes. I also admire Mr. Buffett for the Giving Pledge which he has promoted with the younger Mr. Gates. Under that Pledge, wealthy individuals commit to giving at least half of their wealth to philanthropy.

There is, however, considerable tension between the Buffett commitment to federal estate taxation and the Buffett commitment to philanthropy. By virtue of the estate tax charitable deduction, when a wealthy decedent leaves part or all of his estate to charity, no estate tax is paid on these contributed amounts.

It is perfectly plausible to call for estate taxation only for those who don’t distribute their wealth to philanthropy. It is, however, hard to reconcile that position with Responsible Wealth’s advocacy of strong estate taxation. Mr. Gates, Sr., for example, declared that “it would be shameful to leave potential revenue on the table from those most able to pay.” However, that is precisely what happens when large estates go to charity, namely, estate tax revenue which would otherwise flow to the federal government is instead diverted to charity. Such charity may be worthwhile but it does nothing to reduce the federal deficit.

Similarly, Ms. Disney argued that “a weak estate tax” falls “on the backs of the middle class,” presumably because the federal government will respond to reduced estate tax revenues by deficit financing, by raising other taxes on the middle class or by reducing government spending. However, when an estate is distributed to charity free of estate taxation, the government confronts these same choices.

A compromise could preserve the incentive for charitable giving while also generating some estate tax revenues for the federal government: Limit the estate (and gift) tax charitable deduction.

Many, including President Obama, have suggested such limitations on the income tax charitable deduction. If, for example, an individual is in the 35% federal income tax bracket, the President has proposed that the donor receive a deduction as if he or she were in the 28% bracket. In a similar fashion, the estate tax charitable deduction could be curbed, thereby generating some additional revenues for the federal fisc while also keeping a tax-incentive for charitable giving.

Consider, for example, a billionaire who leaves his entire estate of $1,000,000,000 to charity. To simplify the math, let’s assume that this billionaire would pay estate tax at the 40% rate if he did not bequeath all his assets to philanthropy. Because this $1,000,000,000 bequest is fully deductible for federal estate tax purposes, no tax is paid in this example. If this billionaire had not made this charitable bequest but had instead left his money to his children, the federal government would have received estate tax revenues of $400,000,000.

Suppose now that Congress limits the federal estate tax deduction to 70% of the amount donated to charity. In this case, the billionaire would leave a taxable estate of $300,000,000. At a 40% rate, this would require a federal estate tax payment of $120,000,000.

To provide the cash to pay this tax, this billionaire would probably reduce his charitable bequest to retain cash to pay this estate tax. However, at the end of the day, charity would receive the bulk of this billionaire’s assets while the federal government would receive some estate tax.

A limit on the estate tax charitable deduction could be constructed to fall only on relatively larger estates. For example, the first $10 million of charitable bequests could be fully deductible for estate tax purposes and only the amount gifted over that threshold would be deductible in part.

Alternatively, the limit could be phased in as charitable contributions increase. For example, the first $10 million of charitable bequests could be fully deductible for estate tax purposes. Then the next $50 million of philanthropic gifts could be 90% deductible and any further gifts would be 70% deductible for federal estate tax purposes.

The details are less important than the basic policy: By limiting the estate tax charitable deduction, all large estates donated to philanthropy would pay some federal estate tax revenues at a reduced rate. This would balance the need for federal revenues with the encouragement of the kind of charitable bequests quite commendably encouraged by Mr. Buffett and the Giving Pledge.

Edward A. Zelinsky is the Morris and Annie Trachman Professor of Law at the Benjamin N. Cardozo School of Law of Yeshiva University. He is the author of The Origins of the Ownership Society: How The Defined Contribution Paradigm Changed America. His monthly column appears here.

Edward A. Zelinsky is the Morris and Annie Trachman Professor of Law at the Benjamin N. Cardozo School of Law of Yeshiva University. He is the author of The Origins of the Ownership Society: How The Defined Contribution Paradigm Changed America. His monthly column appears here.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only business and economics articles on OUPblog via email or RSS.

Image credit: Macro shot of the seal of the United States on the US one dollar bill. Photo by briancweed, iStockphoto.

The post Limit the estate tax charitable deduction appeared first on OUPblog.

By: Alice,

on 12/19/2012

Blog:

OUPblog

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

Current Affairs,

drug abuse,

Colorado,

marijuana,

washington,

drug policy,

What Everyone Needs To Know,

federal government,

drug trafficking,

federal law,

*Featured,

Law & Politics,

DEA,

WENTK,

Angela Hawken,

Drug Enforcement Agency,

Jonathan P. Caulkins,

Mark A.R. Kleiman,

state law,

Add a tag

By Jonathan P. Caulkins, Angela Hawken, and Mark A.R. Kleiman

As officials in Washington State and Colorado try to decide how to implement the marijuana-legalization laws passed by their voters last month, officials in Washington, DC, are trying to figure out how to respond. Below, a quick guide to what’s at stake.

WHAT DO THE WASHINGTON AND COLORADO LAWS SAY?

Lots of crucial details remain to be determined, but in outline:

In both states, adults may — according to state but not federal law — possess limited amounts of marijuana, effective immediately.

In both states, there are to be licensed (and taxed) growers and sellers, under rules to take effect later this year.

Sales to minors and possession by minors remain illegal.

Colorado, but not Washington, now allows anyone person over the age of 21 to grow up to six marijuana plants (no more than three of them in the flowering stage) in any “enclosed, locked space,” and to store the marijuana so produced at the growing location. That marijuana can be given away (up to an ounce at a time), but not sold.

HOW MUCH OF THIS CAN THE FEDERAL GOVERNMENT PREVENT?

Paradoxically, the regulated activity permitted by these laws is easy to stop, but the unregulated activity is hard to stop.

Although everything allowed by the new state laws remains forbidden by federal law, if thousands of Coloradans start growing six pot plants each in their basements there wouldn’t be enough DEA agents to ferret them out. The same applies to possession for personal use.

On the other hand, the federal government has ample legal authority to shut down the proposed systems of state-licensed production and sale. Once someone formally applies to Colorado or Washington for permission to commit what remains a federal felony, a federal court can enjoin that person from doing any such thing, and such orders are easily enforced. So the federal government could make it impossible to act as a licensed grower or seller in either state.

Moreover, it could do so at any time. The lists of license-holders will always be available, and at any point they could be enjoined from continuing to act under those licenses. That creates a “wait-and-see” option unusual in law enforcement situations; in general, an illicit activity becomes harder to suppress the larger it is and the longer it has been established.

WHAT IMPACT WILL THE LAWS HAVE ON DRUG ABUSE?

It is possible that removing the state-level legal liability for possession and use of marijuana will increase demand, but there is little historical evidence from other jurisdictions that changing user penalties much affects consumption patterns.

There is no historical evidence concerning how legal production and sale might influence consumption, for the simple reason that no modern jurisdiction has ever allowed large-scale commercial production. But commercialization might matter more than mere legality of use. It could affect consumption by making drugs easier to get, by making them cheaper, by improving quality and reliability as perceived by consumers, and by changing attitudes: both consumer attitudes toward the drugs and the attitudes of others about those who use drugs. How great the impacts would be remains to be seen; it would depend in part on yet-to-be-determined details of the Colorado and Washington systems.

Washington’s legislation is designed to keep the price of legally-sold marijuana about the same as the current price of illegal marijuana. Colorado’s system might allow substantially lower prices. Falling prices would be expected to have a significant impact on consumption, especially among very heavy users and users with limited disposable income: the poor and the young.

WHAT EFFECT WILL THE LAWS HAVE ON DRUG TRAFFICKING?

If the laws affect Mexican drug trafficking organizations at all, the impact will be to deprive them of some, but not the bulk, of their revenues. Transnational drug trafficking organizations currently profiting from smuggling marijuana into the US or organizing its production here cannot gain from increased competition.

The open question is how much, if any, revenue they would lose from either falling prices or reduced market share. The oft-cited figure that the big Mexican drug trafficking groups derive 60% of their drug-export revenue from marijuana trafficking has been thoroughly debunked; the true figure is closer to 25%, and that doesn’t count their ill-gotten gains from domestic Mexican drug dealing or from extortion, kidnapping, and theft. So don’t expect Los Zetas to go out of business, whatever happens in Colorado.

Legal marijuana in Washington State is likely to be too expensive to compete on the national market. But prices in Colorado might be low enough to make legal cannabis from Colorado retailers competitive with illicit sellers of wholesale cannabis as a supply for marijuana dealers in other states. To take advantage of that opportunity, out-of-state dealers could organize groups of “smurfs” to buy one ounce each at multiple retail outlets; a provision of the Colorado law forbids the state from collecting the sort of information about buyers that might discourage smurfing. Marijuana prices might fall substantially nationwide, with harmful impacts on drug abuse but beneficial impacts on international trafficking. (The state government could even gain revenue if Colorado became a national source of marijuana.)

The other wild card in the deck is the Colorado “home-grow” provision. Marijuana producers in Colorado will be able to grow the plant without any risk of enforcement action by the state, and also without any registration requirement or taxation, as long as they grow no more than three flowering plants and three plants not yet in flower at any given location. By developing networks of grow locations each below the legal limit, entrepreneurs could create large-scale production operations with a significant cost advantage over states where growing must be concealed from state and local law enforcement agencies.

Only time will tell whether Colorado “home-grown” could compete with California and Canada in the national and international market for high-potency cannabis or with Mexico in the market for “commercial-grade” cannabis. But the risks imposed by local law enforcement, and the costs of concealment to avoid those risks, constitute such a large share of the costs of illegal marijuana growing that avoiding those costs would constitute a very great competitive advantage, and illicit enterprise has proven highly adaptable to changing conditions.

IS THERE A BASIS FOR A BARGAIN?

Maybe. Federal and state authorities share an interest in preventing the development of large interstate sales from Colorado and Washington, and the whole country might gain from learning about the experience of legalization in those two states: as long as the effects of those laws could be mostly contained within those states. The question is whether the federal government might be willing to let Colorado and Washington try allowing in-state sales while working hard to prevent exports, and whether those states, with federal help (and the threat of a federal crackdown on their licensed growers and sellers if Washington and Colorado product started to show up in New York and Texas), could succeed in doing so. If that happens, it would be vital to have mechanisms in place to learn as much as possible from the experiment.

Things will get even more complex if other states decide to join the party.

So buckle your seat belts; this could be a rather bumpy ride.

Mark A.R. Kleiman, Jonathan P. Caulkins, and Angela Hawken are the authors of Drugs and Drug Policy: What Everyone Needs to Know. Mark A.R. Kleiman is Professor of Public Policy at UCLA, editor of The Journal of Drug Policy Analysis, and author of When Brute Force Fails and Against Excess. Jonathan P. Caulkins is Stever Professor of Operations Research and Public Policy at Carnegie Mellon University. Angela Hawken is Associate Professor of Public Policy at Pepperdine University.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only law and politics articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

The post Semi-legal marijuana in Colorado and Washington: what comes next? appeared first on OUPblog.

By: Alice,

on 12/17/2012

Blog:

OUPblog

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

UKpophistory,

1800-1928,

1928-2008,

Cannabis Britannica,

Cannabis Nation,

Control and consumption in Britain,

ganja,

James H. Mills,

trade and prohibition,

History,

UK,

Current Affairs,

empire,

cannabis,

*Featured,

Law & Politics,

Add a tag

By James H. Mills

It was announced on 10 December as an outcome of the recent Commission into cannabis that the UK Government has decided to reorganise its ‘ganja administration’ with the objective of taxing sales of the drug in order to generate revenues and to control the price in order to discourage excessive consumption. The Government will work with partners from the private sector to ensure that products of a consistent quality are available to consumers. A source at one of the cannabis corporations has stated that they are happy to make a full contribution to the Government’s finances, although critics have argued that they deploy a range of strategies to avoid paying tax.

The Home Affairs Committee’s Ninth Report, with the title Drugs: Breaking the Cycle, generated plenty of controversy early in December when the Prime Minister rejected its recommendation that a Royal Commission on Drugs Policy be established. The controversy may well have been a furore had an announcement along the lines of the above been included in its pages. Yet mention in the Committee’s report of state cannabis monopolies, of the legal consumption of the drug, and of permissive control regimes in faraway countries, invite comparisons to a previous period in British history, as does the Prime Minister’s allusion to a Royal Commission. This was a period when the paragraph above would have raised few eyebrows as British tax collectors skimmed off revenues from some of the world’s largest cannabis consuming societies.

The period, of course, is the 1890s. The Commission in question was the Indian Hemp Drugs Commission which was ordered in the House of Commons in 1893 and which reported in 1894. This Commission was the forerunner of the better known Royal Opium Commission which came to its conclusions in 1895. The enquiry into ‘Indian Hemp’, or cannabis, was focused on the colonial administration in India and its handling of the cannabis trade there. Critics of the opium trade had discovered that the Government of India was also making money from cannabis through a tax on the local market there, and seized on this as further evidence of the corruption of British rule. William Caine, one of the most passionate of these critics declared that cannabis was ‘the most horrible intoxicant the world has yet produced’ and started a campaign that forced the inquiry.

What the inquiry revealed was a thriving market for cannabis products in Britain’s colonies in south Asia. These substances had long-been been used for medication and intoxication there, and complex local beliefs about their uses and dangers were well-established before the British arrived. Colonial scientists and doctors proved to be curious about the potential of cannabis, and William O’Shaughnessy, Professor of Chemistry and Medicine in the Medical College of Calcutta, championed its virtues as a wonder-drug in the 1840s. However, the most sustained interest in the substance on the part of the British was from the Excise officials charged with taxing it as by the 1890s revenue from commercial cannabis was in the region of £150000 per annum, or around nine million pounds in today’s money.

Many of these officials worked readily alongside India’s cannabis producers in the trade. One magistrate reported that ‘they are singularly peaceable and law abiding and they are remarkably wealthy and prosperous’ and went on to note that:

The ganja cultivators contributed amongst them Rs. 5000 for the creation of the Higher English School at Naugaon. If a road or a bridge is wanted, instead of waiting for the tardy action of a District Board or committing themselves to the tender mercies of the PWD the cultivators raise a subscription among themselves and the road or bridge is constructed.

Other British officials were more suspicious of these producers however. As early as the 1870s fears were expressed that all manner of strategies were devised by those in the trade to evade the administration’s efforts to tax it. Storing crops away from the eyes of inspectors, claiming that fires had destroyed full storage facilities and clandestine shipments of the drug were all uncovered. Officials regularly swapped stories like the following:

In December, a couple of police constables and a village watchman were, about 9pm, on their way to Bálihar, when they saw two persons crossing the field with something on their heads. On their shouting out, the men dropped their loads and ran off. It was then found that they had dropped 36 ½ kutcha seers of flat hemp. The drug was taken possession of by the constables but the culprits were never traced.

Perhaps because of such episodes the British continued to tighten their grip on commercial cannabis into the twentieth-century and reforms in the wake of the Indian Hemp Drugs Commission included price fixing, government-controlled warehousing of all crops, and licensing of both wholesale and retail transactions. The example of cannabis-taxation in India was followed elsewhere, with colonial administrations as far apart as Burma and Trinidad abandoning initial attempts at prohibition. In fact it emerged in 1939 that the Government in India had been supplying cannabis to markets in both Burma and Trinidad in contravention of the international controls on the drug that had been imposed in 1925 at the Geneva Opium Conference.

While the Home Affairs Committee is right to look to current experiments with control regimes for cannabis in Washington, Colorado and Uruguay, perhaps the stories above are reminders that British history too provides plenty of evidence for assessing ‘the overall costs and benefits of cannabis legalisation’. These stories provide glimpses of a world where cannabis transactions provide state revenues rather than act as drains on resources, where suppliers club together to pay for educational facilities rather than hang around school-gates plying their wares, and where doctors work freely with a useful drug. But they also seem to warn of the moral complexities of state-sponsored markets in psycho-active substances, and of the problems that any control system will face when confronted by those keen to maximise their profits from such drugs.

James H. Mills is Professor of Modern History at the University of Strathclyde and Director of the Strathclyde hub of the Centre for the Social History of Health and Healthcare (CSHHH) Glasgow. Among his publications are Cannabis Nation: Control and consumption in Britain, 1928-2008, (Oxford University Press 2012), Cannabis Britannica: Empire, trade and prohibition, 1800-1928, (Oxford University Press 2003) and (edited with Patricia Barton) Drugs and Empires: Essays in modern imperialism and intoxication, 100-1930, (Palgrave 2007). The extracts above are all taken from his books.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only law and politics articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Image credit: Photograph of cannabis indica foliage bygaspr13 via iStockphoto.

The post Ganja administration appeared first on OUPblog.

By: Alice,

on 12/17/2012

Blog:

OUPblog

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

targeting,

public international law,

armed conflict,

broadcasting services,

fog of war,

International Criminal Tribunal,

International Human Rights Law,

Law of Non-International Armed Conflict,

lawful attacks,

Marie Colvin,

Sandesh Sivakumaran,

targeting journalists,

Tim Hetheringto,

wartime journalists,

sandesh,

sivakumaran,

Current Affairs,

Media,

journalists,

armed forces,

civilians,

pil,

*Featured,

Law & Politics,

Add a tag

By Sandesh Sivakumaran

The last couple of years have been bad for journalists. I’m not referring to phone-hacking, payments to police, and the like, which have occupied much attention in the United Kingdom these last months. Rather, I’m referring to the number of journalists who have been killed in wartime.

Arab news reporters conduct an on-site interview with 4th Civil Affairs Group Public Affairs Officer Maj. M. Naomi Hawkins in front of the Dr. Talib Al-Janabi Hospital in Fallujah, Iraq, on Dec. 2, 2004. The hospital was one stop during a tour for media to different sites where reconstruction efforts are beginning after the November battle with insurgents. Photo by Cpl. Theresa M. Medina, U.S. Marine Corps.

These last two years alone have seen eminent journalists such as

Marie Colvin and

Tim Hetherington killed while reporting on armed conflicts. Just last month, two journalists were killed while reporting in

Syria. Deaths of journalists during conflicts are not new — Robert Capa and Gerda Taro both died while serving as war photographers. Increasingly, though, we are witnessing the targeting of journalists because they are journalists.

Why are journalists targeted?

Journalists play a critical role in wartime — reporting on events, revealing the horrors of war, investigating abuses by the parties. Their role is a particularly important one given the fog of war. It’s often through media reporting that the public takes notice of a situation and the international community is pushed into action. For these very reasons, journalists are not infrequently viewed as a thorn in the side of the government or the armed group. They may be considered unwanted witnesses to what is going on and targeted for their reporting.

How does the law of armed conflict protect journalists?

The law of armed conflict distinguishes between different types of journalists:

- Journalists who work for media outlets or information services of the armed forces.

- Journalists who accompany the armed forces and are authorized to do so, but who aren’t members of the armed forces, e.g., the embedded reporter.

- Journalists who are undertaking professional activities in areas affected by hostilities but who aren’t accompanying the armed forces, e.g., the broadcaster who is presenting from a conflict zone but who isn’t embedded with the troops.

The first category of journalists constitutes members of the armed forces. Accordingly, they don’t benefit from the protections afforded to civilians and their deaths don’t constitute a violation of the law.

The latter two categories of journalists are civilians. Accordingly, they can’t be attacked, unless and for such time as they take a direct part in hostilities. Reporting on events and investigating abuses committed by the parties can never constitute taking a direct part in hostilities, even if the investigations lead to greater support for one side or another.

Journalists may, however, prove to be casualties of lawful attacks. This is a particular risk for journalists who are embedded with troops. The law allows for the targeting of troops and that targeting may result in bystanders or embedded reporters becoming casualties. In order to judge the legality of such an attack, the law utilizes the principle of proportionality, ie we have to weigh up the expected loss of civilian life, injury to civilians, and damage to civilian objects with the concrete and direct military advantage anticipated. Only where the former is excessive when compared to the latter will the attack be unlawful. Although any loss of life is regrettable, the legal test means that deaths don’t necessarily imply that unlawful acts have been committed.

Particular controversies

One particularly controversial area of the law is the targeting of TV and radio stations. Civilian broadcasting services are protected from attack. They may be legitimate targets, however, if they constitute military objectives. In legal terms, this refers to objects that, “by their nature, location, purpose or use make an effective contribution to military action and whose total or partial destruction, capture or neutralization, in the circumstances ruling at the time, offers a definite military advantage.”

This would render dual purpose broadcasters that broadcast civilian programmes and which are used for military communications possible targets. Civilian broadcasters that broadcast propaganda are not generally considered military objectives, as propaganda doesn’t satisfy the test for a military objective. Thus, following NATO’s targeting of the RTS studio in Belgrade during the conflict in Kosovo, the Committee established by the Prosecutor of the International Criminal Tribunal for the former Yugoslavia to Review the NATO Bombing Campaign against the Federal Republic of Yugoslavia noted that, “if the attack on the RTS was justified by reference to its propaganda purpose alone, its legality might well be questioned by some experts in the field of international humanitarian law” (para. 76). Compare that to Radio Mille Collines, the broadcaster that was inciting genocide in Rwanda and which many people consider a legitimate target. The dividing line is a tricky one to draw.

Sandesh Sivakumaran is Associate Professor and Reader in International Law, University of Nottingham. He is the author of The Law of Non-International Armed Conflict (OUP, 2012), co-editor of International Human Rights Law (OUP, 2010) and recipient of the Journal of International Criminal Justice Giorgio La Pira Prize and the Antonio Cassese Prize. He advises and acts as expert for a range of states, inter-governmental organizations, and non-governmental organizations on issues of international law.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only law and politics articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

The post Killing journalists in wartime: a legal analysis appeared first on OUPblog.

By: ChloeF,

on 12/14/2012

Blog:

OUPblog

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

photo,

Sociology,

images,

image,

Current Affairs,

controversy,

death,

Media,

government,

protest,

circulation,

photograph,

dying,

VSI,

demonstration,

conspiracy,

very short Introductions,

caption,

Iran,

martyrdom,

reprint,

neda,

demonstrations,

mistake,

hate mail,

*Featured,

martyrs,

Law & Politics,

Tehran,

VSIs,

inaccuracy,

Jolyon Mitchell,

martyr,

Neda Agha-Soltan,

agha,

soltani,

soltan,

protestor,

Add a tag

Jolyon Mitchell

A protestor holds a picture of a blood spattered Neda Agha-Soltan and another of a woman, Neda Soltani, who was widely misidentified as Neda Agha-Soltan.

It was agonizing, just a few weeks before publication of Martyrdom: A Very Short Introduction, to discover that there was a minor mistake in one of the captions. Especially frustrating, as it was too late to make the necessary correction to the first print run, though it will be repaired when the book is reprinted. New research had revealed the original mistake. The inaccuracy we had been given had circulated the web and had been published by numerous press agencies and journalists too. What precisely was wrong?

To answer this question it is necessary to go back to Iran. During one of the demonstrations in Tehran following the contested re-election of President Ahmadinejad in 2009, a young woman (Neda Agha-Soltan) stepped out of the car for some fresh air. A few moments later she was shot. As she lay on the ground dying her last moments were captured on film. These graphic pictures were then posted online. Within a few days these images had gone global. Soon demonstrators were using her blood-spattered face on posters protesting against the Iranian regime. Even though she had not intended to be a martyr, her death was turned into a martyrdom in Iran and around the world.

Many reports also placed another photo, purportedly of her looking healthy and flourishing, alongside the one of her bloodied face. It turns out that this was not actually her face but an image taken from the Facebook page of another Iranian with a similar name, Neda Soltani. This woman is still alive, but being incorrectly identified as the martyr has radically changed her life. She later described on BBC World Service (Outlook, 2 October 2012) and on BBC Radio 4 (Woman’s Hour, 22 October 2012) how she received hate mail and pressure from the Iranian Ministry of Intelligence to support the claim that the other Neda was never killed. The visual error made it almost impossible for Soltani to stay in her home country. She fled Iran and was recently granted asylum in Germany. Neda Soltani has even written a book, entitled My Stolen Face, about her experience of being mistaken for a martyr.

The caption should therefore read something like: ‘A protestor holds a picture of a blood spattered Neda Agha-Soltan and another of a woman, Neda Soltani, who was widely misidentified as Neda Agha-Soltan.’ This mistake underlines how significant the role is of those who are left behind after a death. Martyrs are made. They are rarely, if ever, born. Communities remember, preserve, and elaborate upon fatal stories, sometimes turning them into martyrdoms. Neda’s actual death was commonly contested. Some members of the Iranian government described it as the result of a foreign conspiracy, while many others saw her as an innocent martyr. For these protestors she represents the tip of an iceberg of individuals who have recently lost their lives, their freedom, or their relatives in Iran. As such her death became the symbol of a wider protest movement.

This was also the case in several North African countries during the so-called Arab Spring. In Tunisia, in Algeria, and in Egypt the death of an individual was put to use soon after their passing. This is by no means a new phenomenon. Ancient, medieval, and early modern martyrdom stories are still retold, even if they were not captured on film. Tales of martyrdom have been regularly reiterated and amplified through a wide range of media. Woodcuts of martyrdoms from the sixteenth century, gruesome paintings from the seventeenth or eighteenth centuries, photographs of executions from the nineteenth century, and fictional or documentary films from the twentieth century all contribute to the making of martyrs. Inevitably, martyrdom stories are elaborated upon. Like a shipwreck at the bottom of the ocean, they collect barnacles of additional detail. These details may be rooted in history,unintentional mistakes, or simply fictional leaps of the imagination. There is an ongoing debate, for example, around Neda’s life and death. Was she a protestor? How old was she when she died? Who killed her? Was she a martyr?

Martyrdoms commonly attract controversy. One person’s ‘martyr’ is another person’s ‘accidental death’ or ‘suicide bomber’ or ‘terrorist’. One community’s ‘heroic saint’ who died a martyr’s death is another’s ‘pseudo-martyr’ who wasted their life for a false set of beliefs. Martyrs can become the subject of political debate as well as religious devotion. The remains of a well-known martyr can be viewed as holy or in some way sacred. At least one Russian czar, two English kings, and a French monarch have all been described after their death as martyrs.

Neda was neither royalty nor politician. She had a relatively ordinary life, but an extraordinary death. Neda is like so many other individuals who are turned into martyrs: it is by their demise that they are often remembered. In this way even the most ordinary individual can become a martyr to the living after their deaths. Preserving their memory becomes a communal practice, taking place on canvas, in stone, and most recently online. Interpretations, elaborations, and mistakes commonly cluster around martyrdom narratives. These memories can be used both to incite violence and to promote peace. How martyrs are made, remembered, and then used remains the responsibility of the living.

Jolyon Mitchell is Professor of Communications, Arts and Religion, Director of the Centre for Theology and Public Issues (CTPI) and Deputy Director of the Institute for the Advanced Study in the Humanities (IASH) at the University of Edinburgh. He is author and editor of a wide range of books including most recently: Promoting Peace, Inciting Violence: The Role of Religion and Media (2012); and Martyrdom: A Very Short Introduction (2012).

The Very Short Introductions (VSI) series combines a small format with authoritative analysis and big ideas for hundreds of topic areas. Written by our expert authors, these books can change the way you think about the things that interest you and are the perfect introduction to subjects you previously knew nothing about. Grow your knowledge with OUPblog and the VSI series every Friday!

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only VSI articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only articles on law and politics on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Image credit: A protestor holds a picture of a blood spattered Neda Agha-Soltan and another of a woman, Neda Soltani, who was widely misidentified as Neda Agha-Soltan, used in full page context of p.49, Martyrdom: A Very Short Introduction, by Jolyon Mitchell. Image courtesy of Getty Images.

The post Making and mistaking martyrs appeared first on OUPblog.

By: Alice,

on 12/10/2012

Blog:

OUPblog

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

Current Affairs,

Geography,

mars,

place of the year,

POTY,

extraterrestrial,

Social Sciences,

Editor's Picks,

*Featured,

Law & Politics,

outer,

Place of the Year 2012,

poty 2012,

Gérardine Goh Escolar,

Max Planck Encyclopedia of Public International Law,

grubby,

Add a tag

By Gérardine Goh Escolar

The relentless heat of the sun waned quickly as it slipped below the horizon. All around, ochre, crimson and scarlet rock glowed, the brief burning embers of a dying day. Clouds of red dust rose from the unseen depths of the dry canyon — Mars? I wish! We were hiking in the Grand Canyon, on vacation in that part of our world so like its red sister. It was 5 August 2012. And what was a space lawyer to do while on vacation in the Grand Canyon that day? Why, attend the Grand Canyon NASA Curiosity event, of course!

Wait, what? Space lawyers? Have they got their grubby hands on Mars now?

Well, quite the contrary, and in a manner of speaking, space law has been working to keep any grubby hands off Mars. In the heady aftermath of the Soviet launch of Sputnik-1 in 1957, nations flocked to the United Nations to discuss — and rapidly agree upon — the basic principles relating to outer space. Just a decade later, the 1967 Outer Space Treaty was concluded, declaring outer space a global commons, and establishing that the “exploration and use of outer space shall be carried on for the benefit and in the interests of all mankind”. Today, more than half of the world’s nations are Parties to the Outer Space Treaty, and its principles have achieved that hallowed status of international law — custom — meaning that they are binding on all States, Party or not.

More specifically, the 1967 Outer Space Treaty affirmed that outer space, including the Moon, planets, and other natural objects in outer space (such as Mars!), were not subject to appropriation, forbidding States from claiming any property rights over them. Enterprising companies and individuals have sought to exploit what they saw as a loophole in the Treaty, laying claim to extraterrestrial land on the Moon, Mars and beyond, and selling acres of this extraterrestrial property for a pretty penny. One company claims to have sold over 300 million acres of the Moon to more than 5 million people in 176 countries since 1980. The price of one Moon acre from this company starts at USD$29.99 (not including a deep 10% discount for the holiday season) — potentially making the owner of said company a very rich man. Other companies have also started a differentiated pricing model: “The Moon on a Budget” – only USD$18.95 per acre if you wouldn’t mind a view of the Sea of Vapours — vs. the “premiere lunar location” of the Sea of Tranquillity for USD$37.50 per acre. The package includes a “beautifully engraved parchment deed, a satellite photograph of the property and an information sheet detailing the geography of your region of the moon.” Land on Mars comes at a premium: starting at USD$26.97 per acre, or a “VIP” deal of USD$151.38 for 10 Mars acres.

Indeed, the USD$18.95 may be a good price for the paper that the “beautifully engraved parchment deed” is printed on. And that is likely all you will get for your money. Although the Treaty does not also explicitly forbid individuals or corporate entities from laying claim to extraterrestrial property, it does make States internationally responsible for space activities carried out by their nationals. Despite these companies’ belief that the Treaty only prohibits States from appropriating extraterrestrial property, it is disingenuous to say that on Mars and any other natural object in outer space, “apart from the laws of the HEAD CHEESE, currently no law exists.” International law does apply to the use and exploration of outer space and natural extraterrestrial bodies, including Mars. And that international law, including the prohibition on the appropriation of extraterrestrial property, applies equally to individuals and corporate entities through the vehicle of State responsibility in international law, and through domestic enforcement procedures.

Now, that’s not to say that the principle of non-appropriation is popular. It has been questioned by a caucus of concerned publicists, worried that it would stifle commercial interest in the exploration of Mars. Some other publicists — myself included — have come up with proposals for “fair trade/eco”-type uses of outer space that they contend should be an exception to the blanket ban. But the law at the moment stands as it is — Mars cannot be owned. Or bought. Or sold. For many private ventures into outer space, that is a “big legal buzzkill.” These days, it seems, NASA may even land a spacecraft on the asteroid you purport to own and refuse to pay parking charges — and the US federal court will actually dismiss your case as without legal merit. What is the world coming to?

On the bright side, international space law has meant that there has been a lot of international cooperation in outer space. This has mostly kept the peace in outer space (no Star Wars!) and has ensured the freedom of the exploration and use of outer space for the benefit of humanity. International space law has also contributed towards keeping the Martian (and outer space) environment pristine. And in a world where we worry about the future of our own blue planet, maybe having international law keep our grubby hands of her sister Red Planet isn’t such a bad idea after all.

Dr. Gérardine Goh Escolar is Associate Legal Officer at the United Nations. She is also Associate Research Fellow at the International Institute of Air and Space Law at Leiden University, and has taught international law and space law at various universities, including the National University of Singapore, the University of Cologne and the University of Bonn. She was formerly legal officer and project manager at a national space agency, as well as counsel for a satellite-geoinformation data company. She is currently working on her fourth book, International Law and Outer Space (Oxford International Law Library, OUP: forthcoming 2014). All opinions and any errors in this post are entirely her own.

The Max Planck Encyclopedia of Public International Law is a comprehensive online resource containing peer-reviewed articles on every aspect of public international law. Written and edited by an incomparable team of over 800 scholars and practitioners, published in partnership with the Max Planck Institute for Comparative Public Law and International Law, and updated through-out the year, this major reference work is essential for anyone researching or teaching international law. Articles on outer space law, free for a limited time, include: “Moon and Celestial Bodies” ; “Astronauts” ; “Outer Space, Liability for Damage” ; and “Spacecraft, Satellites, and Space Objects”.

Oxford University Press’ annual Place of the Year competition, celebrating geographically interesting and inspiring places, coincides with its publication of Atlas of the World – the only atlas published annually — now in its 19th Edition. The Nineteenth Edition includes new census information, dozens of city maps, gorgeous satellite images of Earth, and a geographical glossary, once again offering exceptional value at a reasonable price. Read previous blog posts in our Place of the Year series.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only law and politics articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Image credit: Valles Marineris is a vast canyon system that runs along the Martian equator. Courtesy NASA/JPL-Caltech/USGS. Image has been altered from the original with the addition of a “FOR SALE” sign.

The post Mars, grubby hands, and international law appeared first on OUPblog.

By: Alice,

on 12/9/2012

Blog:

OUPblog

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

Current Affairs,

What Everyone Needs To Know,

*Featured,

tax cuts,

Law & Politics,

Business & Economics,

fical cliff,

Joel Slemrod,

Leonard E. Burman,

tax and spend,

Taxes in America,

WENTK,

slemrod,

Add a tag

With the ongoing negotiations around the fiscal cliff — what taxes can we raise? what can we cut instead? — we’ve pulled a brief excerpt from Taxes in America: What Everyone Needs to Know by Leonard E. Burman and Joel Slemrod. When heated debates over taxation roil Congress and the nation, a better understanding of our tax system is of vital importance.

Taxes have always been an incendiary topic in the United States. A tax revolt launched the nation and the modern day Tea Party invokes the mantle of the early revolutionaries to support their call for low taxes and limited government.

And yet, despite the passion and the fury, most Americans are remarkably clueless about how our tax system works. Surveys indicate that they have no idea about how they are taxed, much less about the overall contours of federal and state tax systems. For instance, in a recent poll a majority of Americans either think that Social Security tax and Medicare tax are part of the federal income tax system or don’t know whether it is or not, and more than six out of ten think that low-income or middle-income people pay the highest percentage of their income in federal taxes. Neither is correct.

Thus, there is a desperate need for a clear, concise explanation of how our tax system works, how it affects people and businesses, and how it might be made better.

Should tax reform and deficit reduction be separated?

One critical point in the current debate about tax reform is whether it should be revenue-neutral. Some argue that it should be so as to follow the successful blueprint laid out in 1986. Also, many advocates of revenue-neutrality object to tax increases on principle. But some counter that our long-run budget problems are so severe that more revenues will be needed and potentially tying tax reform to lessening future debt burdens could be an effective strategy.

We side with those who think more revenue will be needed and that tax reform should be part of a revenue-raising, deficit-reducing plan. The two go together in that raising revenue is less damaging if done with a more efficient tax system. As discussed below, the Bowles-Simpson deficit reduction plan and the proposal by the Bipartisan Policy Center’s Debt Reduction Task Force both followed this approach. They would eliminate many tax expenditures to finance income tax rate cuts, as in 1986, but reserve some of the revenue gains for deficit reduction. The BPC plan cut fewer tax expenditures, but would introduce a new VAT to augment federal revenues.

Are there some sensible tax reform ideas?

Sure. President George W. Bush put together a blue ribbon panel to propose fundamental tax reform, and they came up with two alternative packages that would have each been simpler and more efficient than the existing tax code. One option would have radically simplified the tax code by eliminating many tax expenditures and converting many of the remaining tax deductions to flat credits. One insight of the Bush tax reform panel was that while tax experts view the standard deduction as a simplification—because people who do not itemize don’t need to keep records on charitable contributions, mortgage payments, taxes, and so on—most real people think it’s unfair that high income people can deduct those items while lower income people can’t. The proposal would have dispensed with itemization.

The “simplified income tax” under the Bush panel’s scheme would have reduced the number of tax brackets and cut top rates, eliminated the individual and corporate alternative minimum tax, consolidated savings and education tax breaks to reduce “choice complexity” and confusion, simplified the Earned Income and Child Tax Credits, simplified taxation of Social Security benefits, and simplified business accounting. The alternative “growth and investment” tax plan would have lowered the taxation of capital income compared with current law—somewhat similar to Scandinavian dual income tax systems.

The Bipartisan Policy Center Debt Reduction Task Force contained a tax reform plan aimed at simplifying the tax code enough so that half of households would no longer have to file income taxes. That plan would create a new value-added tax and use the revenue to cut top individual and corporate income tax rates to 27 percent.

President Obama empaneled another commission, commonly called the Bowles-Simpson Commission (after its two heads) with the mandate to reform the tax code and reduce the deficit. (The Bush panel had been instructed to produce a revenue-neutral plan.) The commission failed to achieve the super-majority required to force legislative consideration, but a majority supported the chairmen’s blueprint. Bowles-Simpson would have eliminated even more tax expenditures than the BPC Task Force, allowing substantial tax rate cuts without the need for a new VAT or other revenue source.

Senators Ron Wyden (D-OR) and Dan Coats (R-IN) produced a more incremental tax reform plan, designed to be revenue-neutral and preserve the most popular tax breaks. It would eliminate the AMT and cut the corporate tax rate to 24 percent while capping individual income tax rates at 35 percent. The cost of these provisions would be offset by closing or scaling back various tax expenditures. The proposal would raise tax rates on high income taxpayers’ long-term capital gains and dividends from 15 to 22.75 percent. It would revise the formula the federal government uses to adjust tax parameters for inflation, generally cutting the revenue cost of annual inflation adjustments. The plan would also reduce businesses’ interest deductions. It would consolidate and simplify individual tax breaks for saving and education. The most radical process change is that the plan would require the IRS to prepare pre-filled tax returns for lower-income filers.

Columbia law professor Michael Graetz has an even more sweeping proposal.6 He proposes to raise the income tax exemption level so high that 100 million households would no longer owe income tax. To make up the lost revenue a new 10 to 15 percent VAT would be enacted. Only families with incomes above $100,000 would have to file an income tax return. The plan would also substantially simplify the income tax for those few who continued to file, but the main simplification would be to take most households off the income tax rolls entirely. (However, households would still have to supply information to claim new refundable tax credits aimed at offsetting the regressivity of the VAT.)

Leonard E. Burman and Joel Slemrod are the author of Taxes in America: What Everyone Needs to Know. Leonard E. Burman is Daniel Patrick Moynihan Professor of Public Affairs at Maxwell School of Syracuse University. Joel Slemrod is Professor of Economics in the Department of Economics and the Paul W. McCracken Collegiate Professor of Business Economics and Public Policy in the Stephen M. Ross School of Business, at the University of Michigan.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only business and economics articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Image credit: Macro shot of the seal of the United States on the US one dollar bill. Photo by briancweed, iStockphoto.

The post Tax reform and the fiscal cliff appeared first on OUPblog.

By: ChloeF,

on 12/7/2012

Blog:

OUPblog

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

meta,

Current Affairs,

government,

Power,

market,

organizations,

state,

VSI,

network,

governing,

politicians,

globalization,

very short Introductions,

laws,

institutions,

European Union,

Governance,

rule,

global economy,

*Featured,

Law & Politics,

corporation,

organisations,

VSIs,

Mark Bevir,

meta-governance,

social practices,

“governance”,

schulz,

bevir,

hollowing,

Add a tag

By Mark Bevir