new posts in all blogs

Viewing: Blog Posts Tagged with: fdr, Most Recent at Top [Help]

Results 1 - 8 of 8

How to use this Page

You are viewing the most recent posts tagged with the words: fdr in the JacketFlap blog reader. What is a tag? Think of a tag as a keyword or category label. Tags can both help you find posts on JacketFlap.com as well as provide an easy way for you to "remember" and classify posts for later recall. Try adding a tag yourself by clicking "Add a tag" below a post's header. Scroll down through the list of Recent Posts in the left column and click on a post title that sounds interesting. You can view all posts from a specific blog by clicking the Blog name in the right column, or you can click a 'More Posts from this Blog' link in any individual post.

By: Priscilla Yu,

on 12/5/2015

Blog:

OUPblog

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

Books,

Sociology,

mental health,

terrorism,

fear,

fdr,

hippocratic oath,

public health,

Franklin D. Roosevelt,

Barry S. Levy,

Victor W. Sidel,

*Featured,

Health & Medicine,

terrorist attack,

Terrorism and Public Health,

A Balanced Approach to Strengthening Systems and Protecting People Second Edition,

Add a tag

In 1933 in the midst of Great Depression, President Franklin D. Roosevelt, in his first inaugural address, wisely stated, “The only thing we have to fear is fear itself.” That wisdom has as much relevance today as it did during the Depression.

The post “The only thing we have to fear is fear itself” appeared first on OUPblog.

By: Daniella Frangione,

on 9/20/2014

Blog:

OUPblog

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

Books,

History,

Biography,

president,

America,

roosevelt,

great depression,

fdr,

Franklin Delano Roosevelt,

Theodore Roosevelt,

slideshow,

Eleanor Roosevelt,

New Deal,

*Featured,

Images & Slideshows,

Add a tag

The Roosevelts: Two exceptionally influential Presidents of the United States, 5th cousins from two different political parties, and key players in the United States’ involvement in both World Wars. Theodore Roosevelt negotiated an end to the Russo-Japanese War and won the 1906 Nobel Peace Prize. He also campaigned for America’s immersion in the First World War. Almost 25 years later, Franklin Delano Roosevelt came into office during the calamitous aftermath of the Great Depression, yet during his 12-year presidency he contributed to the drop in unemployment rates from 24% when he first took office, to a staggering mere 2% when he left office in 1945. Furthermore, the first lady Eleanor Roosevelt encouraged discussion and implementation of women’s rights, World War II refugees, and civil rights of Asian and African Americans even well-after her husband’s presidency and death. Witness the lives of these illustrious figures through this slideshow, and take a look at the first half of 20th century American history through the lives of the Roosevelts.

-

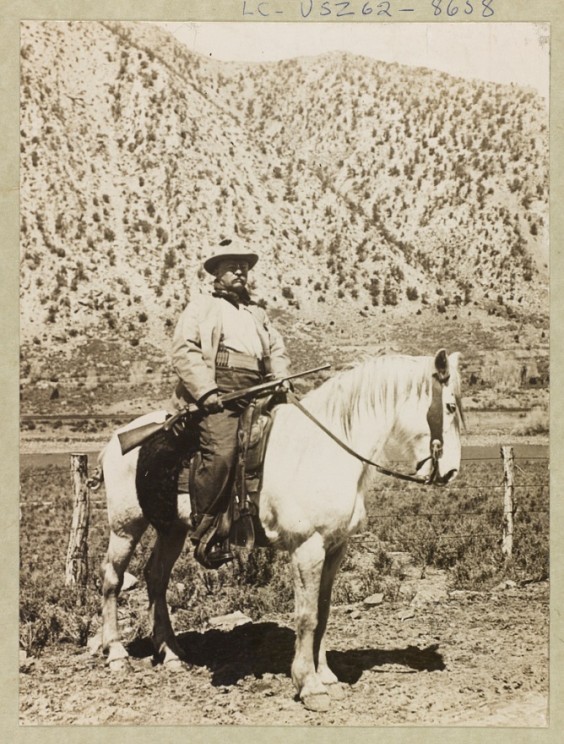

Theodore Roosevelt

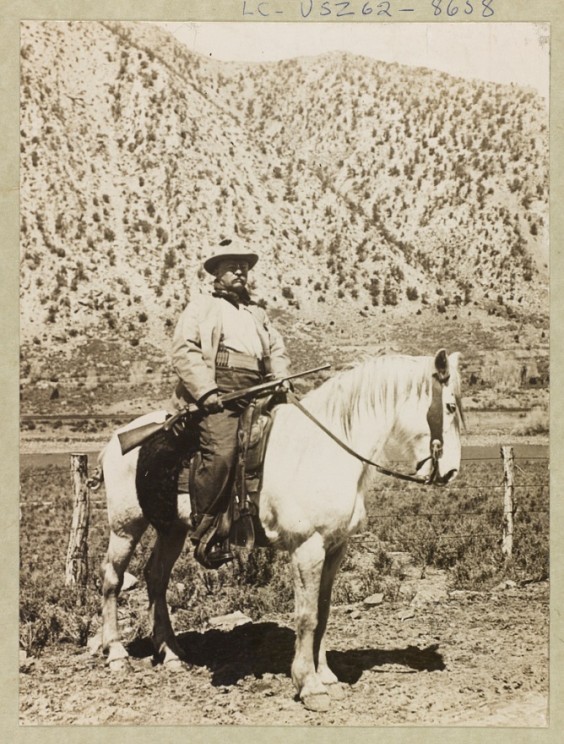

“[Theodore] Roosevelt used his bully pulpit to shape public opinion on many subjects. Conservation of natural resources received special emphasis…. Earlier presidents had done little to protect scenic places and national parks against the wasteful exploitation of the environment…. The president achieved much, creating five national parks, four national game preserves, fifty-one bird reservations, and one hundred and fifty national forests” (Lewis L. Gould, Theodore Roosevelt, 43). Public domain via the Library of Congress

-

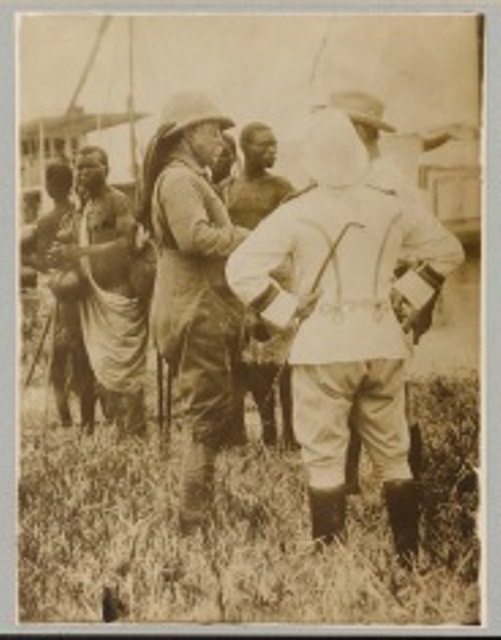

Theodore Roosevelt

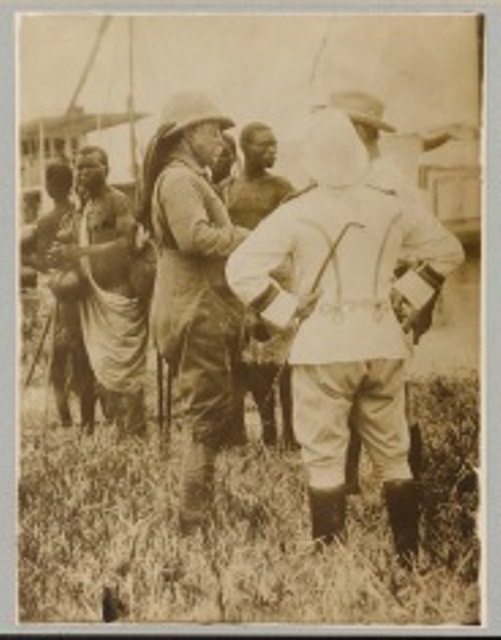

In 1909 and 1910, after finishing his second term as president, Roosevelt traveled to Africa on safari. While abroad, the American public grew increasingly fascinated with Roosevelt and “to satisfy popular demand, [Theodore Roosevelt] recruited a friendly reporter, Warrington Dawson, to recount the progress of the hunt for the press corps. When Roosevelt returned first to Europe and then home in the spring of 1910, it was to intense popular acclaim everywhere.” (Lewis L. Gould, Theodore Roosevelt, 52). TR (center, facing sideways) on safari, 1910. Public domain via the Library of Congress.

-

Theodore Roosevelt and William Howard Taft

“Taft was a first-class lieutenant; but he is only fit to act under orders; and for three years and a half the orders given him have been wrong. Now he has lost his temper and is behaving like a blackguard.” (Theodore Roosevelt to Arthur Lee, dated May 1912, from the Papers of Lord Lee of Fareham.) After leaving office in 1908, Theodore Roosevelt’s relationship with his personally-selected successor, William Howard Taft, soured due to policy differences. Theodore Roosevelt decided to run for an unprecedented third term against President Taft in 1912 as a third-party candidate. Theodore Roosevelt and his newly-founded Progressive Party were ultimately defeated by Democratic candidate Woodrow Wilson in the general election. Theodore Roosevelt and William H. Taft, c. 1909. Public domain via the Library of Congress.

-

Franklin Delano Roosevelt with his mother, Sara

“Franklin grew up in a remarkably cosseted environment, insulated from the normal experiences of most American boys, both by his family’s wealth and by their intense and at times almost suffocating love…. It was a world of extraordinary comfort, security, and serenity, but also one of reticence and reserve.” (Alan Brinkley, Franklin Delano Roosevelt, 4). Franklin Delano Roosevelt with his mother, Sara, 1887. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

-

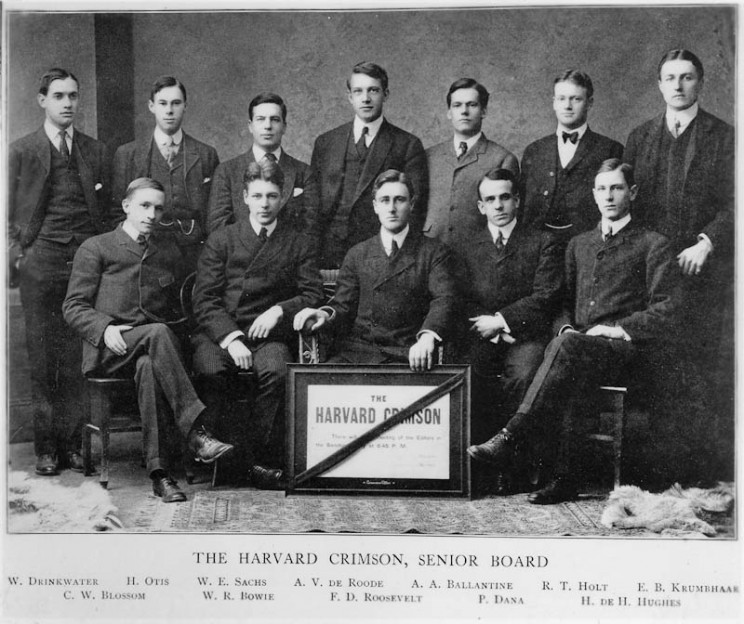

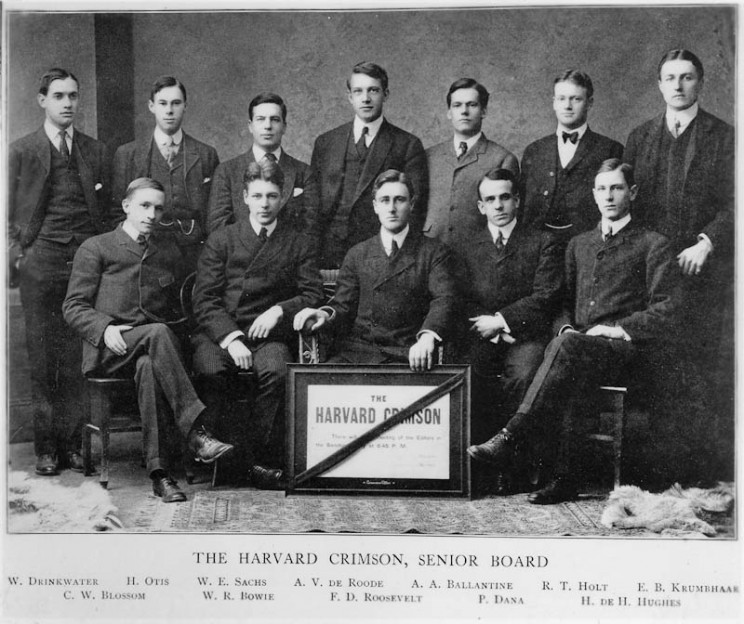

FDR at Harvard

“Entering Harvard College in 1900, [FDR] set out to make up for what he considered his social failures [as a boarding school student at] Groton. He worked hard at making friends, ran for class office, and became president of the school newspaper, the Harvard Crimson, a post that was more a social distinction at the time than a journalistic one. (His own contributions to the newspaper consisted largely of banal editorials calling for greater school spirit.)” (Alan Brinkley, Franklin Delano Roosevelt, 5). FDR as president of the Harvard Crimson, with its Senior Board in 1904. Public domain via the Franklin Delano Roosevelt Library.

-

FDR and Polio

In August of 1921, Roosevelt fell ill after being exposed to the poliomyelitis virus. “He learned to disguise it for pulic purposes by wearing heavy leg braces; supporting himself, first with crutches and later with a cane and the arm of a companion; and using his hips to swing his inert legs forward…So effective was the deception that few Americans knew that Roosevelt could not walk” (Brinkley, Franklin Delano Roosevelt, 18-19). Franklin D. Roosevelt, Fala and Ruthie Bie at Hill Top Cottage in Hyde Park, N.Y . Franklin Delano Roosevelt Library.

-

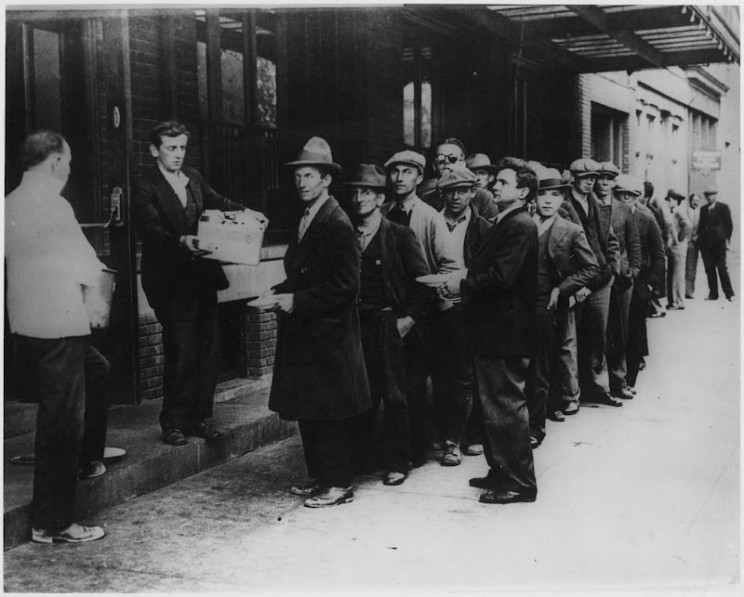

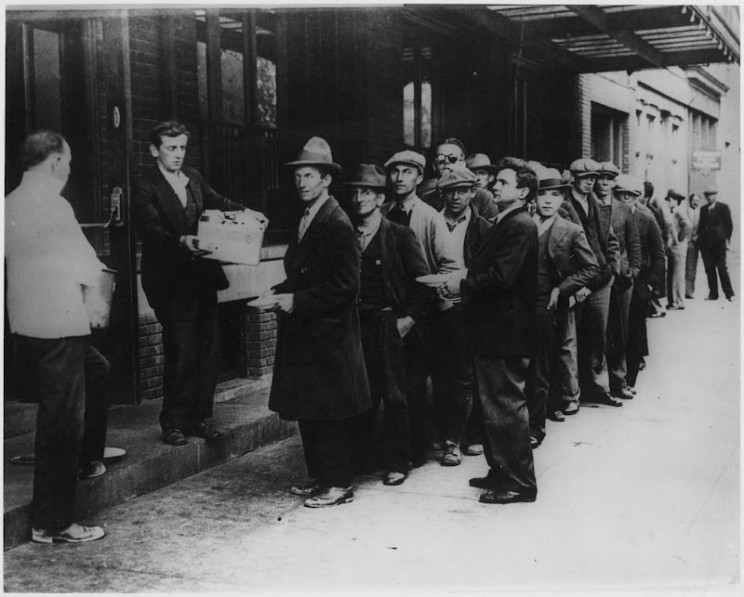

FDR and the Great Depression

Depression breadlines. In the absence of substantial Gov’t relief programs during 1932, free food was distributed with private funds in some urban centers to large numbers of the unemployed. February 1932 Franklin D. Roosevelt Presidential Library & Museum, Photo 69146. Public domain.

-

FDR and the New Deal

“When Franklin Delano Roosevelt took the oath of office as president for the first time on March 4, 1933, every moving part in the machinery of the American economy had evidently broken…. Roosevelt right away began working to repair finance, agriculture, and manufacturing…. The Roosevelt agenda grew by experiment: the parts that worked stuck, no matter their origin. Indeed, the program got its name by just that process: Roosevelt used the phrase “new deal” when accepting the democratic nomination for president, and the press liked it. The “New Deal” said the Roosevelt offered a fresh start, but it promised nothing specific: it worked, so it stuck.” (Rauchway, The Great Depression and the New Deal: A Very Short Introduction, 56). Franklin Roosevelt at desk in Oval Office with group, Washington, D.C. 1933. Library of Congress, Harris & Ewing Collection. Wikimedia Commons.

-

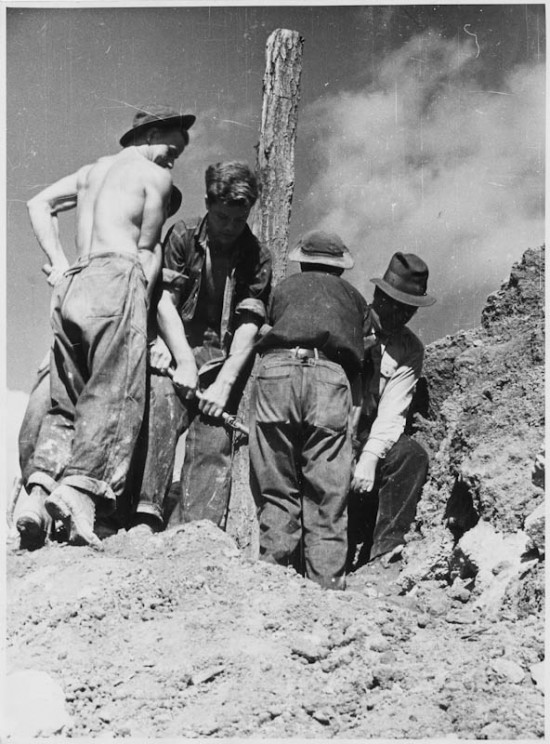

FDR and the New Deal

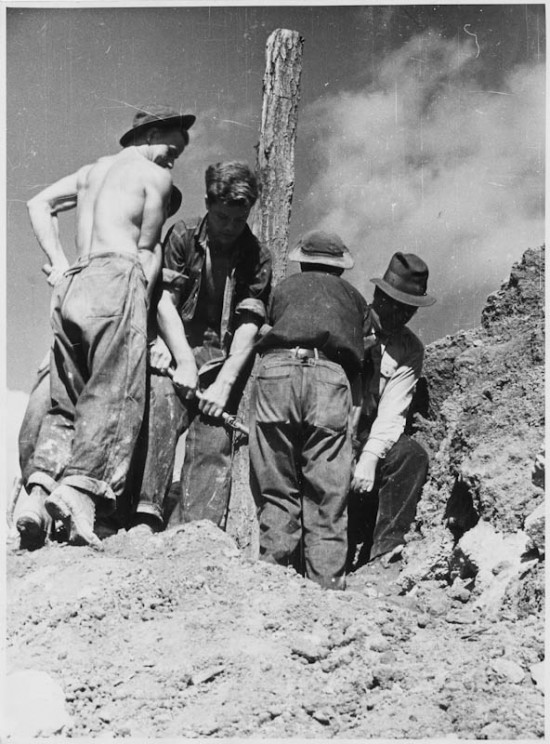

In the beginning of his presidency, Roosevelt proposed a “New Deal.” Over time, it “created state institutions that significantly and permanently expanded the role of federal government in American life, providing at least minimal assistance to the elderly, the poor, and the unemployed; protecting the rights of labor unions; stabilizing the banking system; building low-income housing; regulating financial markets; subsidizing agricultural production…As a result, American political and economic life became much more competitive, with workers, farmers, consumers, and others now able to press their demands upon the government in ways that in the past had usually been available only the corporate world” (Brinkley, Franklin Delano Roosevelt, 61). “CCC boys at work–Prince George Co., Virginia.” Franklin D. Roosevelt Presidential Library & Museum

-

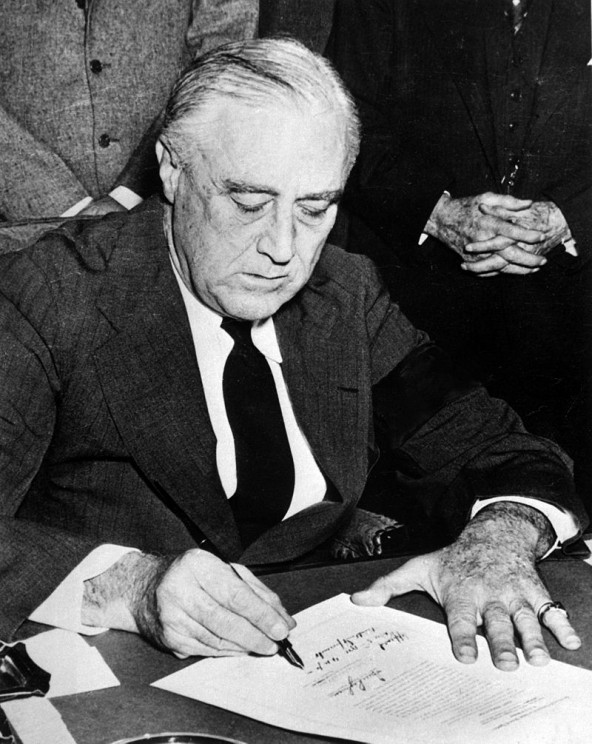

FDR and the Social Security ct

President Roosevelt signed the Social Security Act, at approximately 3:30 pm EST on August 14th, 1935. Standing with Roosevelt are Rep. Robert Doughton (D-NC); Sen. Robert Wagner (D-NY); Rep. John Dingell (D-MI); Rep. Joshua Twing Brooks (D-PA); the Secretary of Labor, Frances Perkins; Sen. Pat Harrison (D-MS); and Rep. David Lewis (D-MD). Library of Congress. Wikimedia Commons.

-

FDR and the Social Security Act

One of the most important pieces of social legislation in American History was The Social Security Act of 1935. The Act was part of Roosevelt’s Second New Deal (from 1935-38). The Social Security Act set up several important programs, including unemployment compensation (funded by employers) and old-age pensions (funded by a Social Security tax paid jointly by employers and employees). It also provided assistance to the disabled (primarily the blind) and the elderly poor (people presumably too old to work). Furthermore, it established Aid to Dependent Children (later called Aid to Families with Dependent Children, or AFDC), which created the model for what most Americans considered “welfare” for over sixty years (Brinkley, Franklin Delano Roosevelt, 51-52). Roosevelt said, “No one can guarantee this country against the dangers of future depressions, but we can reduce those dangers” (Kennedy, Freedom from Fear, 270). This is a poster publicizing Social Security benefits. Public Domain via Franklin D. Roosevelt Library.

-

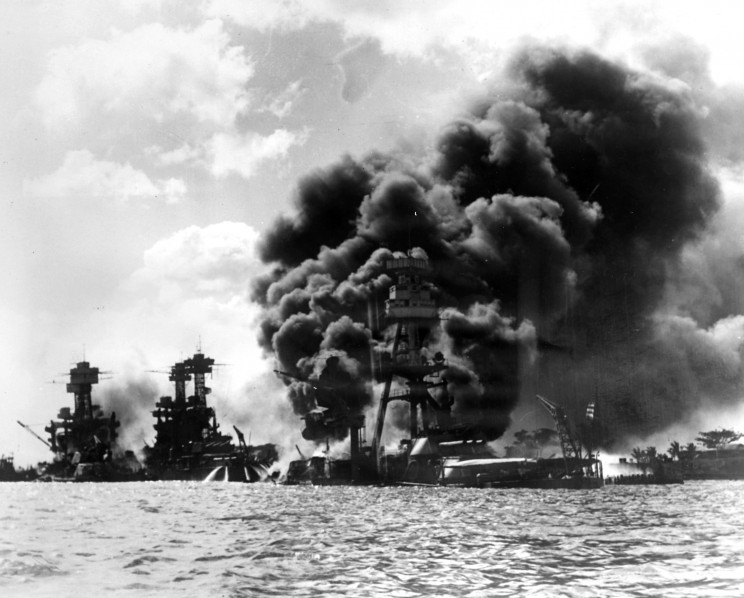

FDR and the Second World War

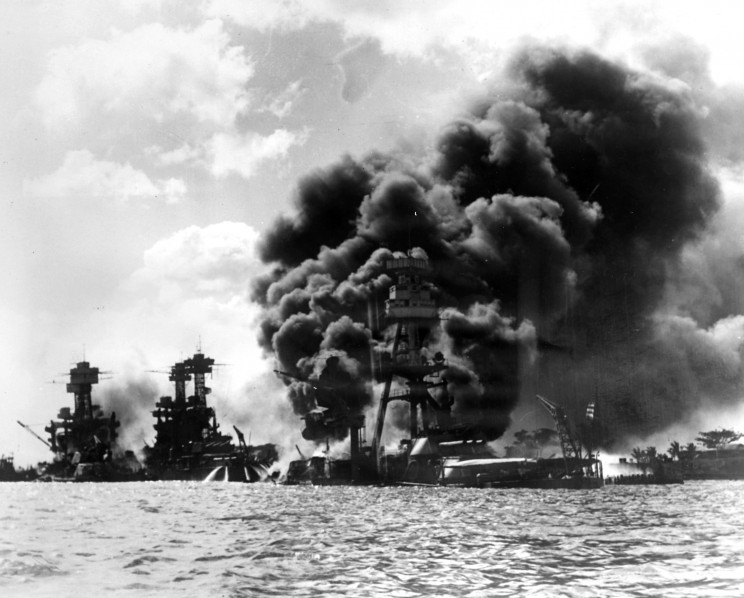

When war finally broke out in Europe in September 1939, Roosevelt continued to insist that the conflict would not involve the United States. Roosevelt declared, “This nation will remain a neutral nation, but I cannot ask that every American remain neutral in thought as well.” Then, on December 7th, 1941, a wave of Japanese bombers struck the American naval base in Pearl Harbor, Hawaii, killing more than 2,000 American servicemen and damaging or destroying dozens of ships and airplanes. Roosevelt called it, “a date which will live in infamy” (Brinkley, Franklin Delano Roosevelt, 68). View looking up “Battleship Row” on 7 December 1941, after the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor. The battleship USS Arizona (BB-39) is in the center, burning furiously. To the left of her are USS Tennessee (BB-43) and the sunken USS West Virginia (BB-48). Official U.S. Navy Photograph. Wikimedia Commons.

-

FDR and the declaration of war

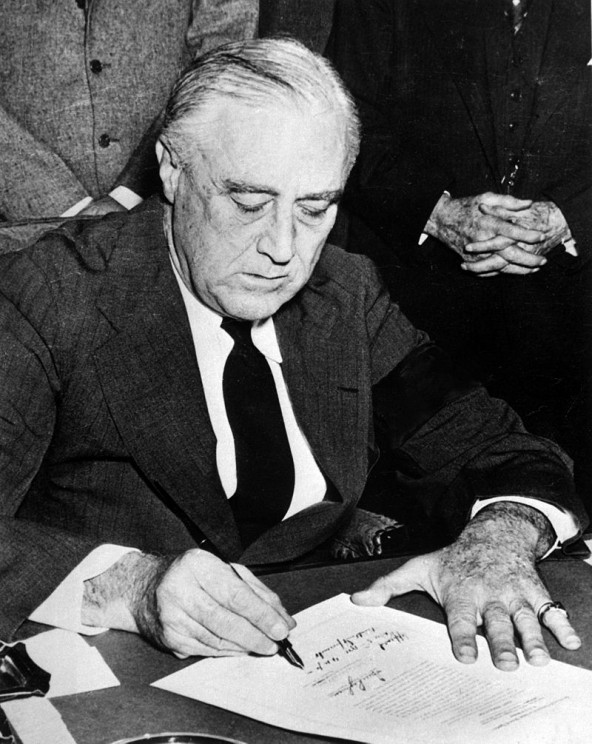

“The Senate and House voted for a declaration of war—the Senate unanimously, and the House by a vote of 388 to 1. Three days later, Germany and Italy, Japan’s European allies, declared war on the United States, and the American Congress quickly and unanimously reciprocated” (Brinkley, Franklin Delano Roosevelt, 75-76). United States President Franklin D. Roosevelt signing the declaration of war against Japan, in the wake of the attack on Pearl Harbor. US National Parks Service via Wikimedia Commons

-

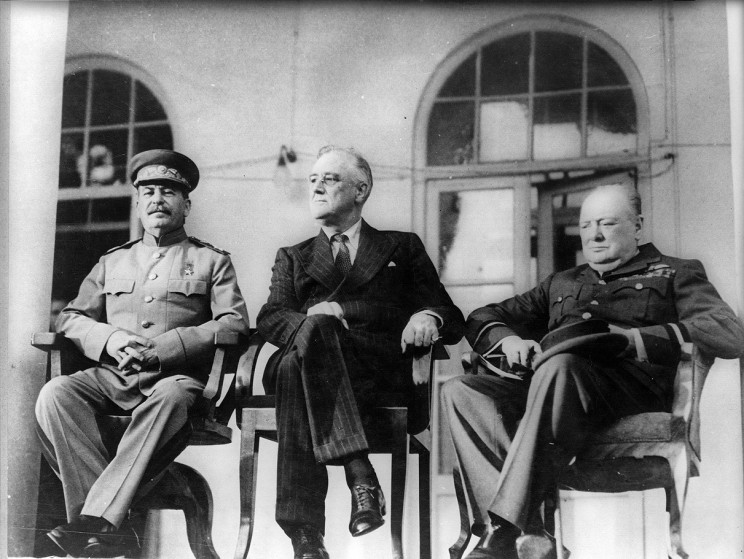

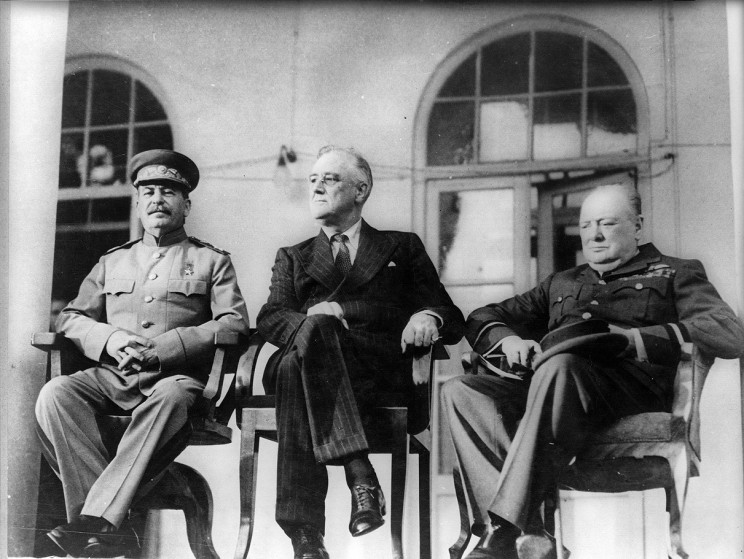

The Big Three

Shown here are ‘The Big Three’: Stalin, U.S. President Franklin D. Roosevelt, and British Prime Minister Winston Churchill at the Tehran Conference, November 1943. At this time, war in eastern Europe had turned decisively in favor of the Soviety Union, which meant that Roosevelt and Churchill now had little leverage over Stalin. Even so, Stalin agreed to enter the Pacific war after the fighting in Europe came to an end. Roosevelt and Churchill promised to launch the long-delayed invasion of France in the spring of 1944 (Brinkley, Franklin Delano Roosevelt, 83). US Signal Corps public domain photo.

-

Eleanor Roosevelt and the Second World War

An outspoken and publicly active First Lady, Eleanor Roosevelt was active both on the homefront and overseas. Her visits drew crowds of people and welcomed her favorably and amiably. This resulted in positive press being written about the Roosevelts across the United States as well as Britain. Eleanor Roosevelt visiting troops in Galapagos Island. US National Archives and Records Administration

-

The Roosevelt Family

Franklin D. Roosevelt and Eleanor Roosevelt with their 13 grandchildren in Washington, D.C. in January of 1945 (Archivist note: This photograph was taken at FDR’s fourth inauguration. This is one of the last family photographs taken before FDR’s death.) Franklin D. Roosevelt Presidential Library & Museum.

-

FDR's death

Franklin Delano Roosevelt died of a stroke in on 12 April 1945. In the decades since his death, his stature as one of the most important leaders of the twentieth century has not diminished. “History will honor this man for many things, however wide the disagreement of many of his countrymen with some of his policies and actions,” the New York Times wrote the day after his death. “It will honor him above all else because he had the vision to see clearly the supreme crisis of our times and the courage to meet that crisis boldly. Men will thank God on their knees, a hundred years from now, that Franklin D. Roosevelt was in the White House” (The New York Times, 13 April 1945). Roosevelt’s funeral procession in Washington in 1945; watched by 300,000 spectators. Library of Congress.

-

Eleanor Roosevelt

The remaining 17 years that Eleanor Roosevelt lived after her husband passed away were years in which she carried out her humanitarian efforts and maintained the integrity of the Roosevelt name. The next President Harry Truman appointed Eleanor as a delegate to the United Nations General Assembly, and less than a year later, she became the first chairperson of the preliminary United Nations Commission on Human Rights. She also chaired the John F. Kennedy administration’s Presidential Commission on the Status of Women. To this day, she is quoted, and referred to with great respect and admiration for her efforts in human rights and politics. Roosevelt speaking at the United Nations in July 1947. Franklin D. Roosevelt Presidential Library and Museum.

Headline image credit: The Roosevelt Family. Library of Congress. The post A visual history of the Roosevelts appeared first on OUPblog.

By: Alice,

on 1/29/2013

Blog:

OUPblog

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

History,

Biography,

US,

hopkins,

roosevelt,

Winston Churchill,

fdr,

Franklin Roosevelt,

Second World War,

Eleanor Roosevelt,

New Deal,

*Featured,

Joseph Stalin,

hopkins’s,

David Roll,

Harry Hopkins,

The Hopkins Touch,

Forging of the Alliance to Defeat Hitler,

33839,

Add a tag

By David Roll

He was a spectral figure in the Franklin Roosevelt administration. Slightly sinister. A ramshackle character, but boyishly attractive. Gaunt, pauper-thin. Full of nervous energy, fueled by caffeine and Lucky Strikes.

Hopkins was an experienced social worker, an in-your-face New Deal reformer. Yet he sought the company of the rich and well born. He was a gambler, a bettor on horses, cards, and the time of day. Between his second and third marriages he dated glamorous women — movie stars, actresses and fashionistas.

It was said that he had a mind like a razor, a tongue like a skinning knife. A New Yorker profile described him as a purveyor of wit and anecdote. He loved to tell the story of the time President Roosevelt wheeled himself into Winston Churchill’s bedroom unannounced. It was when the prime minister was staying at the White House. Churchill had just emerged from his afternoon bath, stark naked and gleaming pink. The president apologized and started to withdraw. “Think nothing of it,” Churchill said. “The Prime Minister has nothing to hide from the President of the United States.” Whether true or not, Hopkins dined out on this story for years.

On the evening of 10 May 1940 — a year and a half before the United States entered the Second World War — Roosevelt and Hopkins had just finished dinner. They were in the Oval Study on the second floor of the White House. As usual, they were gossiping and enjoying each other’s jokes and stories. Hopkins was forty-nine; the president was fifty-seven. They had known one another for a decade; Hopkins had run several of Roosevelt’s New Deal agencies that put millions of Americans to work on public works and infrastructure projects. Franklin and Eleanor Roosevelt had consoled Harry following the death of his second wife, Barbara, in 1937. The first lady was the surrogate mother of Hopkins’s daughter, Diana, age seven. Hopkins had become part of the Roosevelt family. He was Roosevelt’s closest advisor and friend.

The president sensed that Harry was not feeling well. He knew that Hopkins had had more than half of his stomach removed due to cancer and was suffering from malnutrition and weakeness in his legs. Roosevelt insisted that his friend spend the night.

-

Hopkins and Barbara Duncan

http://blog.oup.com/wp-content/uploads/2013/01/hopkinsbarbaraduncan.jpg

Returning to New York after a trip to Europe in the summer of 1934.

-

Hopkins at the 1940 Democratic national convention

http://blog.oup.com/wp-content/uploads/2013/01/hopkins1940demconv.jpg

In Chicago with daughter Diana, age seven. From left to right behind them: John Hertz, founder of the Hertz car rental empire, thoroughbred race horse owner and a close friend of Hopkins; David, Hopkins’ twenty-eight-year-old son; and Edwin Daley

-

Under the fourteen-inch guns of the British battleship Prince of Wales

http://blog.oup.com/wp-content/uploads/2013/01/underguns.jpg

In August 1941, Churchill, Hopkins and British officers discuss the forthcoming meetings with President Roosevelt off the coast of Newfoundland in what became known as the Atlantic Conference.

-

Hopkins conferring with Roosevelt

http://blog.oup.com/wp-content/uploads/2013/01/conferringwroosevelt.jpg

In the Oval Study, June 1942.

-

Rabat, Morocco

http://blog.oup.com/wp-content/uploads/2013/01/morocco.jpg

After visiting American troops in Rabat, Hopkins, General Mark Clark (second from left), Roosevelt, and General George Patton (right) discuss the North Africa campaign during a lunch in the field.

-

Roosevelt celebrating his sixty-first birthday

http://blog.oup.com/wp-content/uploads/2013/01/birthday.jpg

In the roomy cabin of his Boeing Clipper with Admiral Leahy (left), Hopkins and Captain Howard Cone, the Clipper commander (right). They were on the final leg of their return from the Casablanca conference.

-

At the Tehran conference outside the Soviet embassy

http://blog.oup.com/wp-content/uploads/2013/01/tehran.jpg

December 1943, left to right: General George Marshall shaking hands with British Ambassador to the Soviet Union, Archibald Clark Kerr, Hopkins, V. N. Pavlov (Stalin’s interpreter), Joseph Stalin and Vyacheslav Molotov (with mustache).

-

Louise “Louie” Hopkins

http://blog.oup.com/wp-content/uploads/2013/01/louiselouishopkins.jpg

Louise “Louie” Hopkins charmed the Russian officers as she and Harry toured Berlin on their way back from Moscow in June 1945.

Hopkins was the man who came to dinner and never left. For most of the next three-and-one-half years Harry would live in the Lincoln suite a few doors down the hall from the Roosevelts and his daughter would live on the third floor near the Sky Parlor. Without any particular portfolio or title, Hopkins conducted business for the president from a card table and a telephone in his bedroom.

During those years, as the United States was drawn into the maelstrom of the Second World War, Harry Hopkins would devote his life to helping the president prepare for and win the war. He would shortly form a lifelong friendship with Winston Churchill and his wife Clementine. He would even earn a measure of respect and a degree of trust from Joseph Stalin, the brutal dictator of the Soviet Union. He would play a critical role, arguably the critical role, in establishing and preserving America’s alliance with Great Britain and the Soviet Union that won the war.

Harry Hopkins was the pectin and the glue. He understood that victory depended on holding together a three-party coalition: Stalin, Churchill, and Roosevelt. This would be his single-minded focus throughout the war years. Churchill was awed by Hopkins’s ability to focus; he often addressed him as “Lord Root of the Matter.”

Much of Hopkins’s success was due to social savvy, what psychologists call emotional intelligence or practical intelligence. He knew how to read people and situations, and how to use that natural talent to influence decisions and actions. He usually knew when to speak and when to remain silent. Whether it was at a wartime conference, alone with Roosevelt, or a private meeting with Stalin, when Hopkins chose to speak, his words were measured to achieve effect.

At a dinner in London with the leaders of the British press during the Blitz, when Britain stood alone, Hopkins’s words gave the press barons the sense that though America was not yet in the war, she was marching beside them. One of the journalists who was there wrote, “We were happy men all; our confidence and our courage had been stimulated by a contact which Shakespeare, in Henry the V, had a phrase, ‘a little touch of Harry in the night.’”

Hopkins’s touch was not little nor was it light. To Stalin, Hopkins spoke po dushe (according to the soul). Churchill saw Hopkins as a “crumbling lighthouse from which there shown beams that led great fleets to harbour.” To Roosevelt, he gave his life, “asking for nothing except to serve.” They were the “happy few.” And Hopkins had made himself one of them.

David Roll is the author of The Hopkins Touch: Harry Hopkins and the Forging of the Alliance to Defeat Hitler. He is a partner at Steptoe & Johnson LLP and founder of Lex Mundi Pro Bono Foundation, a public interest organization that provides pro bono legal services to social entrepreneurs around the world. He was awarded the Purpose Prize Fellowship by Civic Ventures in 2009.

David Roll is the author of The Hopkins Touch: Harry Hopkins and the Forging of the Alliance to Defeat Hitler. He is a partner at Steptoe & Johnson LLP and founder of Lex Mundi Pro Bono Foundation, a public interest organization that provides pro bono legal services to social entrepreneurs around the world. He was awarded the Purpose Prize Fellowship by Civic Ventures in 2009.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only American history articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

The post Who was Harry Hopkins? appeared first on OUPblog.

By: Alice,

on 9/4/2012

Blog:

OUPblog

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

Current Affairs,

World War II,

Lincoln,

civil war,

Barack Obama,

Vietnam,

gulf war,

George Bush,

fdr,

Nixon,

kissinger,

osama bin laden,

*Featured,

Law & Politics,

Mark Owen,

American Presidency at War,

Andrew Polsky,

Elusive Victories,

Navy SEALs,

No Easy Day,

Add a tag

By Andrew J. Polsky

No Easy Day, the new book by a member of the SEAL team that killed Osama bin Laden on 30 April 2011, has attracted widespread comment, most of it focused on whether bin Laden posed a threat at the time he was gunned down. Another theme in the account by Mark Owen (a pseudonym) is how the team members openly weighed the political ramifications of their actions. As the Huffington Post reports:

Though he praises the president for green-lighting the risky assault, Owen says the SEALS joked that Obama would take credit for their success…. one SEAL joked, “And we’ll get Obama reelected for sure. I can see him now, talking about how he killed bin Laden.”

Owen goes on to comment that he and his peers understood that they were “tools in the toolbox, and when things go well [political leaders] promote it.” It is an observation that invites only one response: Duh.

Of course, a president will bask in the glow of a national security success. The more interesting question, though, is whether it translates into gains for him and/or his party in the next election. The direct political impact of a military victory, a peace agreement, or (as in this case) the elimination of a high-profile adversary tends to be short-lived. That said, events may not be isolated; they also figure in the narratives politicians and parties tell. For Barack Obama and the Democrats in 2012, this secondary effect is the more important one.

Wartime presidents have always been sensitive to the ticking of the political clock. In the summer of 1864, Abraham Lincoln famously fretted that he would lose his reelection bid. Grant’s army stalled at Petersburg after staggering casualties in his Overland campaign; Sherman’s army seemed just as frustrated in the siege of Atlanta; and a small Confederate army led by Jubal Early advanced through the Shenandoah Valley to the very outskirts of Washington. So bleak were the president’s political fortunes that Republicans spoke openly of holding a second convention to choose a different nominee. Only the string of Union victories — at Atlanta, in the Shenandoah Valley, and at Mobile Bay — before the election turned the political tide.

Election timing may tempt a president to shape national security decisions for political advantage. In the Second World War, Franklin Roosevelt was eager to see US troops invade North Africa before November 1942. Partly he was motivated by a desire to see American forces engage the German army to forestall popular demands to redirect resources to the war against Japan, the more hated enemy. But Roosevelt also wanted a major American offensive before the mid-term elections to deflect attention from wartime shortages and labor disputes that fed Republican attacks on his party’s management of the war effort. To his credit, he didn’t insist on a specific pre-election date for Operation Torch, and the invasion finally came a week after the voters had gone to the polls (and inflicted significant losses on his party).

The Vietnam War illustrates the intimate tie between what happens on the battlefield and elections back home. In the wake of the Tet Offensive in early 1968, Lyndon Johnson came within a whisker of losing the New Hampshire Democratic primary, an outcome widely interpreted as a defeat. He soon announced his withdrawal from the presidential race. Four years later, on the eve of the 1972 election, Richard Nixon delivered the ultimate “October surprise”: Secretary of State Henry Kissinger announced that “peace is at hand,” following conclusion of a preliminary agreement with Hanoi’s lead negotiator Le Duc Tho. In fact, however, Kissinger left out a key detail. South Vietnamese President Nguyen Van Thieu balked at the terms and refused to sign. Only after weeks of pressure, threats, and secret promises from Nixon, plus renewed heavy bombing of Hanoi, did Thieu grudgingly accept a new agreement that didn’t differ in its significant provisions from the October version.

But national security success yields ephemeral political gains. After the smashing coalition triumph in the 1991 Gulf War, George H. W. Bush enjoyed strikingly high public approval ratings. Indeed, he was so popular that a number of leading Democrats concluded he was unbeatable and decided not to seek their party’s presidential nomination the following year. But by fall 1992 the victory glow had worn off, and the public focused instead on domestic matters, especially a sluggish economy. Bill Clinton’s notable ability to project empathy played much better than Bush’s detachment.

And so it has been with Osama and Obama. Following the former’s death, the president received the expected bump in the polls. Predictably, though, the gain didn’t persist amid disappointing economic results and showdowns with Congress over the debt ceiling. From the poll results, we might conclude that Owen and his Seal buddies were mistaken about the political impact of their operation.

But there is more to it. Republicans have long enjoyed a political edge on national security, but not this year. The death of Osama bin Laden, coupled with a limited military intervention in Libya that brought down an unpopular dictator and ongoing drone attacks against suspected terrorist groups, has inoculated Barack Obama from charges of being soft on America’s enemies. Add the end of the Iraq War and the gradual withdrawal of forces from Afghanistan and the narrative takes shape: here is a president who understands how to use force efficiently and with minimal risk to American lives. Thus far Mitt Romney’s efforts to sound “tougher” on foreign policy have fallen flat with the voters. That he so rarely brings up national security issues demonstrates how little traction his message has.

None of this guarantees that the president will win a second term. The election, like the one in 1992, will be much more about the economy. But the Seal team operation reminds us that war and politics are never separated.

Andrew Polsky is Professor of Political Science at Hunter College and the CUNY Graduate Center. A former editor of the journal Polity, his most recent book is Elusive Victories: The American Presidency at War. Read Andrew Polsky’s previous blog posts.

Andrew Polsky is Professor of Political Science at Hunter College and the CUNY Graduate Center. A former editor of the journal Polity, his most recent book is Elusive Victories: The American Presidency at War. Read Andrew Polsky’s previous blog posts.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only law and politics articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only American history articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

View more about this book on the

By: Lauren,

on 7/30/2010

Blog:

OUPblog

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

populism,

softened,

Politics,

Al Gore,

American History,

A-Featured,

roosevelt,

Vietnam,

Obama,

Glenn Beck,

fdr,

kerry,

Sarah Palin,

Democrats,

Republicans,

John Kerry,

harvey,

fireside chats,

fireside,

paine,

kaye,

Add a tag

Welcome to the final installment the Politics & Paine series. Harvey Kaye and Elvin Lim are corresponding about Thomas Paine, American politics, and beyond. Read the first post here, and the second post here, and the third post here.

Kaye is the author of the award-winning book, Thomas Paine: Firebrand of Revolution, as well as Thomas Paine and the Promise of America. He is the Ben & Joyce Rosenberg Professor of Social Change & Development and Director, Center for History and Social Change at the University of Wisconsin – Green Bay. Lim is author of The Anti-intellectual Presidency, Assistant Professor of Government at Wesleyan University, and a regular contributor to OUPBlog.

Elvin -

You mention John Kerry’s aversion to invoking democracy. It’s odd that the same John Kerry who spoke before the Senate Foreign Relations Committee back in 1971 on behalf of the “Winter Soldiers” – an organization of antiwar Vietnam vets – could not bring himself to speak openly of Paine in the 2004 campaign. And even more pathetic that Kerry used Reagan’s favorite words from Paine, “We have it in our power…,” when he accepted the Democratic party’s nomination, and yet he did not refer to Paine. Which is to say that Kerry quoted Reagan quoting Paine! Is that plagiarism or flattery? Either way, it amazed me that conservative pundits never made anything of it.

But you ask if I think it’s possible to be both “populist” and “pro-government.” Here I turn to FDR , who did not hesitate to engage popular memory and imagination and mobilize popular energies in favor of recovery, reconstruction, and reform and who most certainly embraced and pursued government action. In a September 1934 Fireside Chat, Roosevelt said: “I believe with Abraham Lincoln, that ‘The legitimate object of government is to do for a community of people whatever they need to have done but cannot do at all or cannot do so well for themselves in their separate and individual capacities.’” And for what it’s worth…FDR was the first president since Jefferson to quote Paine, cite his name, and praise his contributions in a major speech while serving as president (see the Fireside Chat of February 23, 1942 and for audio click here.)

Before we close, I’d just note that in a recent national essay contest sponsored by the Bill of Rights Institute and involving 50,000 high school stude

Alan Brinkley is the Allan Nevins Professor of History at Columbia University,  where he served as provost from 2003 to 2009. His new book, Franklin Delano Roosevelt is a compact biography that elegantly blends FDR’s personal life with his professional one, providing a lens into the president’s struggles with polio and his somewhat distant relationship with the first lady. Below we have excerpted Brinkley’s introduction.

where he served as provost from 2003 to 2009. His new book, Franklin Delano Roosevelt is a compact biography that elegantly blends FDR’s personal life with his professional one, providing a lens into the president’s struggles with polio and his somewhat distant relationship with the first lady. Below we have excerpted Brinkley’s introduction.

Franklin Delano Roosevelt may be the most chronicled man of the twentieth century. He led the United States through the worst economic crisis in the life of the nation and through the greatest and most terrible war in human history. His extraordinary legacy, compiled during dark and dangerous years, remains alive in our own, troubled new century as an inspiring and creative model to many, and as a symbol of excessive government power to many others.

My own awareness of Roosevelt began when I was a child growing up in Washington, D.C., in the 1950s, where the image of FDR was still very much alive. My father, a journalist, had attended some of Roosevelt’s Oval Office press conferences during World War II, and for the rest of his life he remembered them as among the most memorable events of his very eventful life. My mother, a Washington native, never met Roosevelt, but she nevertheless considered him and important figure in her life. I remember her devouring the three volumes of Arthur Schlesinger’s The Age of Roosevelt – which I avidly read as well, years later. Whenever we drove down Pennsylvania Avenue, she would point out the plain granite block in front of the National Archives with the words “Franklin Delano Roosevelt” – and nothing else- inscribed on it. He had requested that it be his only monument in Washington. (Beginning in 1997, it was overshadowed by the elaborate Roosevelt Memorial near the National Mall)

When I was in college, working on a senior thesis, I made my first trip to the Roosevelt Library in Hyde Park, New York – the nation’s oldest presidential library, built during Roosevelt’s lifetime. I was struck by its modesty. It was nothing like the grandiose marble and glass structures of many subsequent presidential sites, but a simple fieldstone structure sprawling across the pasture in front of the house in which Roosevelt had grown up. The house was, and still is, open to the public, and it suggests some of the contradictions in Roosevelt’s life. It was clearly the home of a wealthy and aristocratic family, and thus very different from the homes of the millions of common people who idolized him. It was furnished by his mother in expensive, Parisian style, but on its walls were dozens of framed political cartoons and pictures of political events. And to his mother’s dismay, there were often large gatherings of rumpled politicians, smoking, drinking, and talking loudly. Throughout the rooms and the grounds, there were also ramps, constructed to allow Roosevelt to move around his property in a wheelchair because his lifeless legs – unbeknownst to most of his contemporaries – could no longer carry him. A person of wealth and privilege in his youth, he grew up to be a disabled man who made his way to greatness through will power, empathy, and commitment.

During the years in which I have been a historian, I have written about many people, including some of Roosevelt’s most implacable opponents. But I have found myself drawn again and again to the story of this enigmatic m

By: Rebecca,

on 5/22/2009

Blog:

OUPblog

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

Altschuler,

Blumin,

New Deal,

History,

Law,

Education,

Politics,

Current Events,

American History,

A-Featured,

A-Editor's Picks,

veterans,

memorial day,

G.I. Bill,

fdr,

Add a tag

One of the best tributes to our fallen troops, in my opinion, is taking very good care of their surviving comrades. To celebrate Memorial Day we have excerpted a piece  from the beginning of The G.I. Bill: A New Deal For Veterans, by Glenn C. Altschuler and Stuart M. Blumin which looks at just how beneficial the G.I Bill was not only for troops but for all of America. Altschuler is the Thomas and Dorothy Litwin Professor of American Studies and the Dean of the School of Continuing Education and Summer Sessions at Cornell University. Stuart M. Blumin is Professor Emeritus of American History, Cornell University.

from the beginning of The G.I. Bill: A New Deal For Veterans, by Glenn C. Altschuler and Stuart M. Blumin which looks at just how beneficial the G.I Bill was not only for troops but for all of America. Altschuler is the Thomas and Dorothy Litwin Professor of American Studies and the Dean of the School of Continuing Education and Summer Sessions at Cornell University. Stuart M. Blumin is Professor Emeritus of American History, Cornell University.

In July 1995 President Bill Clinton spoke at a commemorative service in Warm Springs, Georgia, soon after the fiftieth anniversary of the death of Franklin Delano Roosevelt. Looking back on FDR’s long and remarkable presidency, Clinton identified as its “most enduring legacy” an achievement that came neither from the Hundred Days of initial New Deal legislation nor from the structural reforms of the Second New Deal, nor even from FDR’s successful prosecution of World War II. Rather, Clinton pointed to the Servicemen’s Readjustment Act of 1944-The GI Bill- a law passed late in Roosevelt’s presidency, following his initiatives but shaped by many others besides himself.  The GI Bill, Clinton observed, “gave generations of veterans a chance to get an education, to build strong families and good lives, and to build the nation’s strongest economy ever, to change the face of America.” This one piece of legislation, he continued, perhaps with an eye to his own presidential legacy, “helped unleash a prosperity never before known.” It was a New Deal for veterans and, through them, for the postwar nation as a whole.

The GI Bill, Clinton observed, “gave generations of veterans a chance to get an education, to build strong families and good lives, and to build the nation’s strongest economy ever, to change the face of America.” This one piece of legislation, he continued, perhaps with an eye to his own presidential legacy, “helped unleash a prosperity never before known.” It was a New Deal for veterans and, through them, for the postwar nation as a whole.

Fifty years earlier this would have seemed a very strange choice for an FDR encomium, but by the 1990s it was as reasonable as choosing Social Security, the WPA, or victory over the Nazis. When Clinton spoke, praise for the GI Bill was widespread and partook of the increasing respect and nostalgia among the vast majority of Americans for what the journalist Tom Brokaw would soon call “the Greatest Generation”-the young adults (many of them boys and girls who quickly became adults) who, in foxholes and bombers, shipyards and munitions factories, helped rescue the world from fascism. The very large numbers who had served in the military during the war returned to help create a peacetime society of unprecedented prosperity, and it came to be generally understood that the GI Bill was the essential instrument of their successful reintegration into civilian life. Clinton, himself a postwar “baby boomer,” spoke for a generation of Americans who saw the GI Bill as the key to a kingdom of peace and plenty.

Praise for the GI Bill was is by no means restricted to members of FDR’s political party. Bob Michel, a former Republican congressman from Peoria, Illinois, who served as minority leader in the House of Representatives for fourteen years (the longest minority leadership in U.S. history), has described the GI Bill as “a great piece of legislation” that “cut across the economic strata” and made it possible for “many thousands of veterans, including tens of thousands who would not have thought of college,” to get undergraduate degrees. Michel points to the almost universal approval of the bill. “I don’t know of anyone,” he reflects, “who has ever maligned it.” Michel was himself a highly decorated World War II veteran and a beneficiary of the GI Bill. Nonetheless, it is clear that his admiration for this legislation is not just informed by his own good fortune but also reflects the experiences of an entire generation.

Leaders from outside politics have also expressed admiration for the GI Bill, and these include many who do not ordinarily favor forceful government solutions to pressing social issues. Two years before Clinton’s Warm Springs address the widely respected management theorist Peter F. Drucker wrote that future historians might welcome to regard the bill as “the most important event of the 20th century” in that its provisions for government-subsidized college education for World War II veterans “signaled the shift to the knowledge society.” Drucker’s was a sophisticated appraisal of how one public initiative could, even as a largely unintended effect, unleash larger forces that would in turn transform an entire society. His analysis reinforces, too, the popular perception of the bill as a product of bipartisan consensus, when what seemed to matter at the moment of its passage was not Democratic or Republican political advantage but the interests of the veterans and the nation at large. It bears the stamp of neither party. It is an American document, a mid-twentieth-century Bill of Rights. The American Legion, pressing hard from late 1943 for its version of a comprehensive veterans’ bill, originally called it the Bill of Rights for GI Joe and GI Jane.

As is suggested by this language of rights and of GI Joe and Jane, much popular praise for the bill has been more personal than that of public leaders asked or inclined to reflect on its general significance. It was what gave your father or grandmother or some elderly veteran who told you his story the opportunity to realize in his or her own lifetime what could have been only distant dreams while in a foxhole in the Ardennes, in a field hospital in Italy, or in a breadline during the Great Depression. Personal success stories that trace back to the GI Bill abound within families and well beyond, some of them known to us, to be sure, because, like Bob Michel’s, they involved famous people.

The GI Bill-assisted career of William Rehnquist, former chief justice of the Supreme Court, is one such story. Rehnquist had a brief taste of college life at Kenyon College before entering the U.S. Army Air Corps in 1942. When his military service was finished, he used the GI Bill to enroll at Stanford University (he was attracted by the California climate), where he earned bachelor’s and master’s degrees in political science and eventually a law degree. He became a clerk for Supreme Court Justice Robert Jackson, and the rest, as they say, is history. When asked years later how he had chosen his profession, Rehnquist answered, perhaps with tongue in cheek, “The GI Bill paid for an occupation test that told you what you ought to be. They told me to be a lawyer.”

For some months now I have been talking to author and illustrator Cheryl Harness via email. She a wonderfully warm, funny, and clever lady. To try to give you sense of what she is like I am going to be having several 'conversations' with her over the next few weeks.

Cheryl have illustrated numerous books that were written by  other people, and she has both written and illustrated many titles as well. Her National Geographic biographies are both fascinating to read and a joy to look at. Her books include such titles as The Remarkable Benjamin Franklin, Franklin and and Eleanor, and The Remarkable, Rough-Riding Life of Theodore Roosevelt and the Rise of Empire America

other people, and she has both written and illustrated many titles as well. Her National Geographic biographies are both fascinating to read and a joy to look at. Her books include such titles as The Remarkable Benjamin Franklin, Franklin and and Eleanor, and The Remarkable, Rough-Riding Life of Theodore Roosevelt and the Rise of Empire America

Here is my first talk with Cheryl:

Marya: Good morning Cheryl. It is a pleasure to have you here on the TTLG

blog with me. I hope you are having a terrific 2009 so far.

Cheryl: I am indeed; so far so good. The December snow & ice has melted, so for today, at least, there's sure footing and the sky is blue.

Marya: We had a sort of white Christmas, but snow has been almost non-existent since then. This is a little disappointing for me because I love to ski.

Recently you told me that you got to look at the cover of the new book

that you are working on. This book is about Harry Truman. I was

wondering what got you interested in writing about this particular

president.

Cheryl: Well, as you and your readers may or may not know, Independence,

Missouri, is my home town. This is true, too, of our 33rd President. Neither of us were born here - he was born south a ways from here in Lamar, MO, 125 years ago; I in Maywood, CA, when he was the president, in 1951.

I actually saw him only once, in person even though we lived in the same neighborhood. I wasn't curious enough, youth being wasted on the young. I was more interested in drawing pictures and reading Laura Ingalls Wilder books. Anyway, I've been asked more than once, "When are you going to do a book about Harry?" Turned out that the answer was "these past few months."

Marya: When will this book be in bookstores?

Cheryl: The book will be available mid-February, in time for Presidents' Day, but I wouldn't expect to see The Harry Book (The Life of President Truman in Words & Pictures) in bookstores any time soon. I'm self- publishing this. It's something I've never done before and I confess that I am a much better writer and illustrator than I am a businesswoman. I imagine that one who goes to my website will find how he or she can get a copy. Or lots of copies! And I reckon that I'll have a bundle of Harry Books with me when I travel about, school visiting. It's comic book - did I tell you that? NO, I didn't! It's 48 pages' worth of pen & ink detailed pictures & lettering about this truly remarkable fellow. I learned so much about my long-gone neighbor. I wish I hadn't been such a doofus and had met him when I was young and had the chance... ah well.

Marya: You have written about several presidents so far including Teddy

Roosevelt and Abraham Lincoln. Which president interested you the most and why?

Cheryl: Indeed, I should say Mr. Lincoln, this year being the 200th anniversary of the year in which he entered the world - same day, by the way, as Charles Darwin, the naturalist. And truly, I loved learning, writing, and illustrating his inspiring life, but of all the presidents - of all the Americans I've studied Teddy Roosevelt is the most interesting. Not saying I agree with all of his politics, but that TR was a fabulous individual. I love stories of overcoming and considering Abe's poverty- stricken background, FDR's polio, Geo. Washington's steadfastness in the face of truly aweful obstacles, TR's early illness - golly, I could go on and on. These individuals overcame so much. And too, each president represents to me a different chapter in the history of our nation.

Marya: I am also fascinated by Teddy Roosevelt's story. He was smart, funny, very active, and full of energy. And, like FDR, he had to overcome a severe illness. In TR's case it was asthma. In general I love reading biographies and books about history. What is it about history that excites you so much?

Cheryl: It's EVERYTHING! All we've done and hoped and dared. All humankind's accomplishments, our cruel, ridiculous, short-sighted mistakes; our explorations and our digging out of the holes we've dug.

And it's positively thick with role models. Me being such a sissypants, I'm ever drawn to courageous examples down the years. Harriet Quimby totally interests me these days. the first woman to fly across the English Channel, in 1912. Hugely brave & skillful PLUS she was totally beautiful, not that it matters, and she died far too young. a real pioneer. Plus, historical, real-life stories go well with my sort of illustration.

Marya: For those of you who don't know, Cheryl's artwork is full of detail and action, and she is a wizz when it comes to maps. Do you have any plans to branch out into fiction?

Cheryl: I did do that a few years ago in my novel for young readers, Just For You to Know [HarperCollins, 2006] It was set here in Independence, MO, 1963. Harry Truman had a brief, cameo appearance in it. That book was my heart's darling. I've got another book in the works - several really - and one of them might well involve another President. Stay tuned!

Marya: That's right! I remember the book because I reviewed - and loved - it. Here is

my review. I look forward to seeing more works of both fiction and non-fiction with your name on them. Thank you for the chat Cheryl.

Cheryl: You are welcome.

I will be talking to Cheryl some more about her life and her work in the weeks to come. In the meantime do please visit

Cheryl's website to find out more about this wonderful lady.

David Roll is the author of

David Roll is the author of

where he served as provost from 2003 to 2009. His new book,

where he served as provost from 2003 to 2009. His new book,

The GI Bill, Clinton observed, “gave generations of veterans a chance to get an education, to build strong families and good lives, and to build the nation’s strongest economy ever, to change the face of America.” This one piece of legislation, he continued, perhaps with an eye to his own presidential legacy, “helped unleash a prosperity never before known.” It was a New Deal for veterans and, through them, for the postwar nation as a whole.

The GI Bill, Clinton observed, “gave generations of veterans a chance to get an education, to build strong families and good lives, and to build the nation’s strongest economy ever, to change the face of America.” This one piece of legislation, he continued, perhaps with an eye to his own presidential legacy, “helped unleash a prosperity never before known.” It was a New Deal for veterans and, through them, for the postwar nation as a whole.