new posts in all blogs

Viewing: Blog Posts Tagged with: VSIs, Most Recent at Top [Help]

Results 1 - 18 of 18

How to use this Page

You are viewing the most recent posts tagged with the words: VSIs in the JacketFlap blog reader. What is a tag? Think of a tag as a keyword or category label. Tags can both help you find posts on JacketFlap.com as well as provide an easy way for you to "remember" and classify posts for later recall. Try adding a tag yourself by clicking "Add a tag" below a post's header. Scroll down through the list of Recent Posts in the left column and click on a post title that sounds interesting. You can view all posts from a specific blog by clicking the Blog name in the right column, or you can click a 'More Posts from this Blog' link in any individual post.

By: KatherineS,

on 7/29/2016

Blog:

OUPblog

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

History,

Politics,

congress,

America,

Jimmy Carter,

Very Short Introductions,

white house,

Lyndon Johnson,

Democrats,

Republicans,

house of representatives,

barry goldwater,

Social Sciences,

*Featured,

donald a. ritchie,

american politics,

VSIs,

United States Senate,

US Congress,

2016 presidential election,

congressional election,

The U.S. Congress: A Very Short Introduction,

VSIs Online,

Add a tag

The primaries, the conventions, and the media have focused so much attention on the presidential candidates that it’s sometime easy to forget all the other federal elections being held this year, for 34 seats in the Senate and 435 in the House (plus five nonvoting delegates). The next president’s chances of success will depend largely on the congressional majorities this election will produce.

The post This year’s other elections appeared first on OUPblog.

By: KatherineS,

on 7/22/2016

Blog:

OUPblog

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

q&a,

VSI,

Very Short Introductions,

Taylor Swift,

*Featured,

VSIs,

Life at Oxford,

staff q&a,

VSI online,

Katie Stileman,

staff interview,

VSI series,

Add a tag

Katie Stileman works as the UK Publicist for Oxford University Press's Very Short Introductions series (VSIs). She tells us a bit about what working for OUP looks like. If she wasn't working on publicity at OUP, she would be doing publicity for Taylor Swift.

The post A Q&A with Katie Stileman, Publicist for the VSI series appeared first on OUPblog.

By: Connie Ngo,

on 3/13/2015

Blog:

OUPblog

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

History,

Biography,

Politics,

american history,

women's history month,

America,

VSI,

very short introduction,

Very Short Introductions,

women's history,

American National Biography,

Editor's Picks,

*Featured,

american politics,

VSIs,

Susan Ware,

VSI online,

American Women's History,

American Women's History: A Very Short Introduction,

Shirley Chisholm,

Add a tag

March is Women’s History Month and as the United States gears up for the 2016 election, I propose we salute a pathbreaking woman candidate for president. No, not Hillary Rodham Clinton, but Shirley Chisholm, who became the first woman and the first African American to seek the nomination of the Democratic Party for president. And yet far too often Shirley Chisholm is seen as just a footnote or a curiosity, rather than as a serious political contender who demonstrated that a candidate who was black or female or both belonged in the national spotlight.

The post Unbossed, unbought, and unheralded appeared first on OUPblog.

By: PennyF,

on 4/11/2014

Blog:

OUPblog

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

Literature,

writing,

Technology,

National Library Week,

contemporary fiction,

VSI,

Very Short Introductions,

Humanities,

*Featured,

VSIs,

Robert Eaglestone,

‘techne’,

eaglestone,

Add a tag

In honor of the beginning of National Library Week this Sunday, 13 April 2014, we’re sharing this interesting excerpt from Contemporary Fiction: A Very Short Introduction. As technology continues to evolve, the way we access books and information is changing, and libraries are continuously working to keep up-to-date with the latest resources available. Here, Robert Eaglestone presents the idea of the seemingly simple act of writing as a form of technology.

The essential thing about technology is that, despite our iPhones and computers and digital cameras and constant change, it is not new at all. In fact, human civilization over the longest possible time grew up not just hand in hand with technology but because of technology. Technology isn’t just something added to ‘being human’ the way we might acquire another gadget: the essence of technology is in the creation of tools, technology in the creation of farming and in buildings, cities, roads, and machines. (p. 87) And perhaps the most important form of technology is right here in front of you, you’re looking at it right now, this second: writing. It too—these very letters here, now—is, of course, a technology. Writing is a ‘machine’ to supplement both the fallible and limited nature of our memory (it stores information over time) and our bodies over space (it carries information over distances). So it’s not so much that we humans made technology: technology also made us. As we write, so writing makes us. It is technology that allows us history, as a recorded past and so a present, and so, perhaps a future. So to think about technology, and changes in technology, is to think about the very core of what we, as a species, are and about how we are changing. As we change technology, we change ourselves. And all novels, because they are a form of technology, implicitly or explicitly, do this.

The word ‘technology’ comes from the Greek word ‘techne’: techne is the skill of the craftsman or woman at building things (ships, tables, tapestries) but also, interestingly, the skill of crafting art and poetry. ‘Techne’ is the skill of seeing how, say, these pieces of wood would make a good table if sanded and used in just that way, or seeing the shape of David in the block of marble, or in hearing how these phrases will best represent the sadness you imagine Queen Hecuba feels in mourning her husband and sons. It’s also the skill, in our age, of working out how best to use resources to eliminate a disease globally, or to deliver high-quality education. But ‘techne’ has become more than just skill: it is a whole way of thinking about the world. In this ‘technological thinking’, everything in the world is turned into a potential resource for use, everything is a tool for doing something. Rocks become sources of ore; trees become potential timber for carpentry or pulp for paper; the wind itself is captured by a windmill or, in a more contemporary idiom, ‘farmed’ in a wind farm. Companies have departments of ‘human resources’. Even an undeveloped piece of natural land, purposely left undisturbed by buildings and agriculture, becomes a ‘wilderness park’, a ‘machine’ in which to relax and recharge (p. 88) oneself from the strains of everyday life. Great works of literature are turned into a resource through which to measure people, by exams or in quizzes. This is the point of the old saw, ‘To a man with a hammer, everything looks like a nail’: to a technological way of thinking, everything looks like a resource to be used (just as to a carpenter, all trees look like potential timber; to a university academic, all fiction is a source of exam questions). More than this, the modern networks which use these resources are bigger and more complex. Where once the windmill ground the miller’s corn to make bread, now a huge global food system moves food resources about internationally: understanding and using these networks are a career in themselves. This technological thinking, rather than the tools it produces, is a taken-for-granted ‘framework’ in which we come to see and understand everything. Although many people have made this sort of observation about the world, the influential and contentious German philosopher Martin Heidegger, from whom much of the above is drawn, made it most keenly.

Is this a bad thing? It certainly sounds as if it might be. Who wants, after all, to be seen only as a ‘human resource’? It’s precisely technological thinking that has put the world at risk of total destruction. On the other hand, technology has offered so much to so many: in curing illness and alleviating pain, for example. The question is too big to answer in these simple terms of ‘bad’ or ‘good’. However, contemporary fiction seems very negative about technology, positing dystopias and awful ends for humanity. However, I want to suggest that contemporary fiction doesn’t find the world utterly without hope, precisely because of technology.

Robert Eaglestone is Professor of Contemporary Literature and Thought at Royal Holloway, University of London. He is Deputy Director (and formerly Director) of the Holocaust Research Centre. His research interests are in contemporary literature and literary theory, contemporary philosophy, and on Holocaust and genocide studies. He is the author of Contemporary Fiction: A Very Short Introduction and Doing English: A Guide for Literature Students (third revised edition) (Routledge, 2009).

The Very Short Introductions (VSI) series combines a small format with authoritative analysis and big ideas for hundreds of topic areas. Written by our expert authors, these books can change the way you think about the things that interest you and are the perfect introduction to subjects you previously knew nothing about. Grow your knowledge with OUPblog and the VSI series every Friday, subscribe to Very Short Introductions articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS, and like Very Short Introductions on Facebook.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only literature articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

The post Writing as technology appeared first on OUPblog.

By: ChloeF,

on 2/22/2013

Blog:

OUPblog

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

Current Affairs,

South Korea,

Korea,

VSI,

Asia,

missile,

bomb,

North Korea,

nuclear,

nuclear weapons,

Korean War,

korea’s,

nuclear program,

*Featured,

regime,

VSIs,

missiles,

ballistic missiles,

ICBM,

Intercontinental Ballistic Missiles,

Joseph M. Siracusa,

Joseph Siracusa,

nucelar,

Pyongyang,

very short introductons,

weaponry,

pyongyang’s,

Add a tag

By Joseph M. Siracusa

Any discussion of North Korea’s nuclear program should begin with an understanding of the limited information available regarding its development. North Korea has been very effective in denying external observers any significant information on its nuclear program. As a result, the outside world has had little direct evidence of the North Korean efforts and has mainly relied on indirect inferences, leaving substantial uncertainties.

Moreover, because its nuclear weapons program wasn’t self-contained, it has been especially difficult to determine how much external assistance arrived and from where, and to assess the program’s overall sophistication.

That said, what is known is that Pyongyang has tested three nuclear devices: in 2006, 2009, and, of course most recently, on 12 February 2013. They have all had varying degrees of success, and North Korea has put considerable effort into developing and testing missiles as possible delivery vehicles.

February’s detonation of a “smaller and light” nuclear device — presumably, part of the plan to build a small atomic weapon to mount on a long-range missile — was the first test carried out by Kim Jong Eun, the young, third-generation leader, following in the footsteps of his father and grandfather. And while it always intriguing to speculate on who is running the show in North Korea, the finger generallyseems to point to the military.

Many foreign observers have come to believe the otherwise desperate, hungry population (and failing regime?) that make up North Korea’s secretive police state is best symbolized by its nuclear and missile programs. Which gives rise to the basic question: what, then, is Pyongyang’s motivation for its nuclear and missile programs? Is it, as Victor Cha once asked, for swords, shields, or badges?

In other words, are the programs intended to provide offensive weapons, defensive weapons, or symbols of status? In spite of prolonged diplomatic negotiations with Pyongyang officials over the past two decades, the question of motivation remains elusive.

Pyongyang’s interest in obtaining nuclear weaponry, beginning around the mid-1950s, has apparently stemmed in part from what it perceived as the US’s nuclear threats and concerns about the nuclear umbrella that protects South Korea. These threats, in turn, have pervaded North Korean strategic thought and action since the Korean War.

These actions may be gauged as offensive or defensive, but Pyongyang officials were at one point fearful of South Korea’s nuclear ambitions and later uncertain about the US emphasis on tactical nuclear weapons and its nuclear “first use” policy in defense of the South. These nuclear-armed additions included 280mm artillery shells, rockets, cruise missiles, and mines.

Against this backdrop, all of North Korea’s nuclear activities tend to focus on a single goal: preservation of the regime. Possessing nuclear weapons would diminish the US’s threat to the nation’s independence, but it could also reduce Pyongyang’s dependence upon China for its security.

Against this backdrop, all of North Korea’s nuclear activities tend to focus on a single goal: preservation of the regime. Possessing nuclear weapons would diminish the US’s threat to the nation’s independence, but it could also reduce Pyongyang’s dependence upon China for its security.

North Korean officials, too, may feel that a small nuclear force offers some insurance against South Korea’s dynamic economic growth and its eventual conventional military superiority.

Pyongyang undoubtedly views its burgeoning nuclear arsenal as a symbol of the regime’s legitimacy and status, which would assist in keeping the Stalinist dynasty in power. Additionally enhanced status would, of course, assist in gaining diplomatic leverage.

Although the North Koreans have boasted about their nuclear deterrent’s ability to hold the US and it allies at bay, it is fairly clear that North Korea has vastly overstated its ability to strike, in part because of the limited amount of fissile material available to Pyongyang and also because of its inability to field a credible delivery option for its nuclear weapons.

The North Koreans have launched long-range ballistic missiles in 1998, 2006, 2009, and 2012, with limited success. By comparison, the US test fires its new missiles scores of times to ensure that they are operationally effective. North Korea would need many more tests of all the systems, independently and together, at a much higher rate than one every few years, to have confidence the missile would even leave the launch pad, let alone approach a target with sufficient accuracy to destroy it.

This was dramatically demonstrated on 13 April 2012, by the failure of the much-hyped effort to employ a three-stage missile, which would send a satellite into space. If the missile was, as Washington and Tokyo believed, a disguised test of an ICBM, the fact that it crashed into the sea shortly after launch illustrated that North Korea’s development and testing of missiles as possible delivery vehicles had miles to go.

Joseph M. Siracusa is Professor in Human Security and International Diplomacy and Associate Dean of International Studies, at the Royal Melbourne Institute of Technology, Melbourne, Australia. Among his numerous books are included: Nuclear Weapons: A Very Short Introduction (2008) and A Global History of the Nuclear Arms Race: Weapons, Strategy, and Politics, 2 vols., with Richard Dean Burns (2013).

The Very Short Introductions (VSI) series combines a small format with authoritative analysis and big ideas for hundreds of topic areas. Written by our expert authors, these books can change the way you think about the things that interest you and are the perfect introduction to subjects you previously knew nothing about. Grow your knowledge with OUPblog and the VSI series every Friday!

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only VSI articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS

Image credit: North Korea Theater Missile Threats, By Institute for National Strategic Studies (INSS.) Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

The post North Korea and the bomb appeared first on OUPblog.

By: ChloeF,

on 2/15/2013

Blog:

OUPblog

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

VSI,

leadership,

pope,

very short introduction,

figure,

mother teresa,

catholic,

cardinal,

vatican,

Pope Benedict XVI,

Pope Benedict,

catholicism,

Humanities,

sistine chapel,

*Featured,

benedict,

Pope John Paul II,

VSIs,

Joseph Ratzinger,

abdicate,

Father Gerald O'Collins,

Gerald O'Collins,

St Peter's,

Religion,

Christians,

Current Affairs,

church,

global,

christian,

Dalai Lama,

Add a tag

By Gerald O’Collins, SJ

“Pope Benedict is 78 years of age. Father O’Collins, do you think he’ll resign at 80?” “Brian,” I said, “give him a chance. He hasn’t even started yet.” It was the afternoon of 19 April 2005, and I was high above St Peter’s Square standing on the BBC World TV platform with Brian Hanrahan. The senior cardinal deacon had just announced from the balcony of St Peter’s to a hundred thousand people gathered in the square: “Habemus Papam.” Cardinal Joseph Ratzinger had been elected pope.

Less than an hour earlier, white smoke pouring from a chimney poking up from the Sistine Chapel let the world know that the cardinal electors had chosen a successor to Pope John Paul II. The bells of Rome were supposed to ring out the news at once. But it took a quarter of an hour for them to chime in. When Hanrahan asked me why the bells hadn’t come in on cue, I pointed the finger at local inefficiency: “We’re in Italy, Brian.”

I was wrong. The keys to t he telephone that should have let someone contact the bellringers were in the pocket of the dean of the college of cardinals, Joseph Ratzinger. He had gone into a change room to put on his white papal attire, and didn’t hand over the keys until he came out dressed as pope.

he telephone that should have let someone contact the bellringers were in the pocket of the dean of the college of cardinals, Joseph Ratzinger. He had gone into a change room to put on his white papal attire, and didn’t hand over the keys until he came out dressed as pope.

One of the oldest cardinals ever to be elected pope, after less than eight years in office Benedict XVI has now bravely decided to retire or, to use the “correct” word, abdicate. His declining health has made him surrender his role as Bishop of Rome, successor of St Peter, and visible head of the Catholic Christendom. He no longer has the stamina to give the Church the leadership it deserves and needs.

Years ago an Irish lady, after watching Benedict’s predecessor in action, said to me: “He popes well.” You didn’t need to be a specialized Vatican watcher to notice how John Paul II and Benedict “poped” very differently.

A charismatic, photogenic, and media-savvy leader, John Paul II proved a global, political figure who did as much as anyone to end European Communism. He more or less died on camera, with thousands of young people holding candles as they prayed and wept for their papal friend dying in his dimly lit apartment above St Peter’s Square.

Now Benedict’s papacy ends very differently. He will not be laid out for several million people to file past his open coffin. His fisherman’s ring will not be ceremoniously broken. There will be no official nine days of mourning or funeral service attended by world leaders and followed on television or radio by several billion people. He will not be lifted high above the crowd like a Viking king, as his coffin is carried for burial into the Basilica of St Peter’s. The first pope to use a pacemaker will quietly walk off the world stage.

In my latest book, an introduction to Catholicism, I naturally included a (smiling) picture of Pope Benedict. But he pales in comparison with the photos of John Paul II anointing and blessing the sick on a 1982 visit to the UK; meeting the Dalai Lama before going to pray for world peace in Assisi; in a prison cell visiting Mehmet Ali Agca, who had tried to assassinate him in May 1981; and hugging Mother Teresa of Calcutta after visiting one of her homes for the destitute and dying.

In my latest book, an introduction to Catholicism, I naturally included a (smiling) picture of Pope Benedict. But he pales in comparison with the photos of John Paul II anointing and blessing the sick on a 1982 visit to the UK; meeting the Dalai Lama before going to pray for world peace in Assisi; in a prison cell visiting Mehmet Ali Agca, who had tried to assassinate him in May 1981; and hugging Mother Teresa of Calcutta after visiting one of her homes for the destitute and dying.

Yet the bibliography of that introduction contains no book written by John Paul II either before or after he became pope. But it does contain the enduring classic by Joseph Ratzinger, Introduction to Christianity (originally published 1967). Both as pope and earlier, it was through the force of his ideas rather than the force of his personality that Benedict XVI exercised his leadership.

The public relations record of Pope Benedict was far from perfect. He will be remembered for quoting some dismissive remarks about Islam made by a Byzantine emperor. That 2006 speech in Regensburg led to riots and worse in the Muslim world. Many have forgotten his visit later that year to the Blue Mosque in Istanbul when he turned towards Mecca and joined his hosts in silent prayer.

Catholics and other Christians around the world hope now for a forward-looking pope who can offer fresh leadership and deal quickly with some crying needs like the ordination of married men and the return to the local churches of the decision-making that some Vatican offices have arrogated to themselves.

When he speaks at midday from his apartment to the people gathered in St Peter’s Square on 24 February, the last Sunday before his resignation kicks in, Pope Benedict will be making his final public appearance before the people of Rome. A vast crowd will have streamed in from the city and suburbs to thank him with their thunderous applause. They cherished the clear, straightforward language of his sermons and homilies, and admire him for what will prove the defining moment of his papacy—his courageous decision to resign and pass the baton to a much younger person.

Gerald O’Collins received his Ph.D. in 1968 at the University of Cambridge, where he was a research fellow at Pembroke College. From 1973-2006, he taught at the Gregorian University (Rome) where he was also dean of the theology faculty (1985-91). Alone or with others, he has published fifty books, including Catholicism: A Very Short Introduction and The Second Vatican Council on Other Religions. As well as receiving over the years numerous honorary doctorates and other awards, in 2006 he was created a Companion of the General Division of the Order of Australia (AC), the highest civil honour granted through the Australian government. Currently he is a research professor of theology at St Mary’s University College,Twickenham (UK).

The Very Short Introductions (VSI) series combines a small format with authoritative analysis and big ideas for hundreds of topic areas. Written by our expert authors, these books can change the way you think about the things that interest you and are the perfect introduction to subjects you previously knew nothing about. Grow your knowledge with OUPblog and the VSI series every Friday!

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only VSI articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only religion articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Image Credits: Pope Benedict XVI during general audition By Tadeusz Górny, public domain via Wikimedia Commons; Church of the Carmine, Martina Franca, Apulia, Italy. Statues of Mother Teresa and Pope John Paul II By Tango7174, creative commons licence via Wikimedia Commons

The post The abdication of Pope Benedict XVI appeared first on OUPblog.

By: ChloeF,

on 2/8/2013

Blog:

OUPblog

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

History,

African American Studies,

African,

VSI,

Values,

society,

marijuana,

jamaica,

very short Introductions,

heritage,

divine,

*Featured,

Rastafari,

western values,

VSIs,

downpression,

ecological backlash,

Ennis B. Edmonds,

Rasta,

Rastafarian,

rastas,

Add a tag

By Ennis B. Edmonds

Recently, I was discussing my academic interest with an acquaintance from my elementary school days. On revealing that I have researched and written about the Rastafarian movement, I was greeted with a look of incredulity. He followed this look with a question: “How has Rastafari assisted anyone to progress in life?” My friend assured me he was aware that prominent and accomplished Rastas exist in Jamaica, however he was convinced that Rastafari did not contribute to the social and economic mobility of most of its adherents. Sensing that my friend was espousing a notion of progress based on rising social status and increasing economic resources — reflecting his own journey from a peasant farming family to an elementary school teacher to a highly regarded principal of a number of schools to an educational officer at present — I pointed out that Rastafari rejects this conventional notion of progress, especially when it is for a few at the exclusion of the many. Pointing out that I had no understanding of Rastafari until I started researching it, I left hoping that next time he engages in a conversation on Rastafari, he will do so with greater understanding and appreciation.

Unfortunately, my acquaintance’s attitude towards Rastafari is widely shared by those who judge progress and personal worth by social mobility and increasing material resources within a Western cultural f ramework. Conversely, Rastafari has articulated a trenchant critique of Western values and institutions, asserting that they are based on exploitation and oppression of both humans and the environment. Western values and institutions have sown seeds of discord, distrust, and conflict that translate into social disharmony and all the social ills that plague contemporary societies. The rapacious exploitation of natural resources in pursuit of profit have violated sound ecological principles and will ultimately trigger an ecological backlash (are we already experiencing this in changing weather patterns?). In this respect, Rastafari is an implicit call for us to examine the foundation on which our political, economic, and cultural institutions and values are constructed. Are they designed to cater to the interest of the whole human family or the interest of those who monopolize and manipulate power? Are they informed by a desire to live in harmony with other humans and nature or by a desire to dominate both?

ramework. Conversely, Rastafari has articulated a trenchant critique of Western values and institutions, asserting that they are based on exploitation and oppression of both humans and the environment. Western values and institutions have sown seeds of discord, distrust, and conflict that translate into social disharmony and all the social ills that plague contemporary societies. The rapacious exploitation of natural resources in pursuit of profit have violated sound ecological principles and will ultimately trigger an ecological backlash (are we already experiencing this in changing weather patterns?). In this respect, Rastafari is an implicit call for us to examine the foundation on which our political, economic, and cultural institutions and values are constructed. Are they designed to cater to the interest of the whole human family or the interest of those who monopolize and manipulate power? Are they informed by a desire to live in harmony with other humans and nature or by a desire to dominate both?

But Rastafari is much more than a critique of Western society; it is a fashioning of an identity grounded in a sense of the human relationship to the Divine and to the African heritage of most of its adherents. Thus for Rastas, the Divine is not just some transcendent, ethereal being, but an essential essence in all humans and a cosmic presence that pervades the universe. To be Rasta is to be awakened to one’s innate divine essence and to strive to live one’s life in harmony with the divine principles that govern the world, instead of living like “baldheads” (non-Rastas) who are sometimes driven to excess in their pursuit of ego-satisfaction. On a more cultural level, Rastafari seeks to cultivate for its adherents an identity and a lifestyle based on a re-appropriation on an African past. Rejecting the slave and post-slavery identity foisted upon them by colonial powers, early Rastas and their successors turned to their African heritage to reconstitute their cultural selves. Despite the derogation of Africa and the denigration of Africans in colonial discourse, Rastas proudly affirm themselves as Africans and posit that an African sense of spirituality that embraces communality and living in harmony with the forces of nature is not only in line with divine principles, but also makes for a more harmonious relationship among humans and a more sustainable future for the earth.

Many of us approach Rastafari from a sense of curiosity inspired by the dramatic imagery that dreadlocks present, rumours we have heard about the copious use of ganja (marijuana) by its adherents, or the realization that the enchanting rhythms and conscious lyrics of reggae are Rasta-inspired. However, a closer look will make us realize that Rastafari presents us with a perspective that can help us ask questions about the mainstream values and institutions of Western society and beyond. Do these values and institutions promote freedom, justice, harmony, opportunity, and sustainability? Long before the Arab Spring and the Occupy Movement, Rastafari has been criticizing the “downpression,” inequities, and unsustainability of the political and economic structures of the world. How about how we regard our human selves? Are we just cogs in the wheel of an economic machine? Or do we have intrinsic value that is enhanced by living in harmony with other humans and our natural environment? You need not embrace Rastafari to appreciate Marley’s lyrics from “Survival”:

Click here to view the embedded video.

“In this age of technological inhumanity/Scientific atrocity/Atomic misphilosophy/Nuclear misenergy/It’s a world that forces lifelong insecurity.” Part of the liner notes from the album of the same name points the way out of this state of affairs: “But to live as one, equal in the eyes of the Almighty.”

Ennis B. Edmonds is Assistant Professor of African-American Religions and American Religions at Kenyon College, Ohio. His areas of expertise are African Diaspora Religions, Religion in America, and Sociology of Religion. His research has focused primarily on Rastafari, leading to Rastafari: From Outcasts to Culture Bearers and Rastafari: A Very Short Introduction.

The Very Short Introductions (VSI) series combines a small format with authoritative analysis and big ideas for hundreds of topic areas. Written by our expert authors, these books can change the way you think about the things that interest you and are the perfect introduction to subjects you previously knew nothing about. Grow your knowledge with OUPblog and the VSI series every Friday and like Very Short Introductions on Facebook.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only VSI articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Image credit: Judah Lion, By Weweje [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons

The post Appreciating the perspective of Rastafari appeared first on OUPblog.

By: ChloeF,

on 2/1/2013

Blog:

OUPblog

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

film,

Video,

films,

students,

submissions,

Media,

Multimedia,

competition,

guardian,

VSI,

the guardian,

very short introduction,

chloe,

very short Introductions,

longlist,

film competition,

*Featured,

TV & Film,

VSIs,

entrants,

Guardian competition,

very short film,

VSI competition,

YouTuve,

longlisted,

on guardian,

Add a tag

The Very Short Film competition was launched in partnership with The Guardian in October 2012. The longlisted entries are now available for the public vote which will produce four finalists. After a live final in March, the winner will receive £9000 towards their university education.

By Chloe Foster

After more than three months of students carefully planning and creating their entries, the Very Short Film competition has closed and the longlisted submissions have been announced.

The competition asked entrants to create a short film which would inform and inspire us. Students were free to base their entry on any subject they were passionate about. There was just one rule: films could be no longer than 60 seconds in length.

We certainly had many who managed to do this. The standard of films was impressive. How were we to whittle down the entries and choose just 12 for the longlist?

We received a real range of films from a variety of ages, characters and subjects — everything from scuba diving to the economic state of the housing market. It was great to see a mixture of academic subjects and topics of personal interest.

It must be said that the quality of the filmmaking itself was very high in some entries. However not all of these could be put through to the longlist; although artistic and clever, they didn’t inform us in the way our criteria specified.

When choosing the longlisted entries, judges looked for students who were clearly on top of their subject. We were most impressed by films that conveyed a topic’s key information in a concise way, were delivered with passion and verve, and left us wanting to find out more. By the end of our selection process, we felt that each of the films had taught us something new or made us think about a subject in a way we hadn’t before.

The sheer amount of information filmmakers managed to convey was astounding. As the Very Short Introductions editor Andrea Keegan says: “I thought condensing a large topic into 35,000 words, as we do in the Very Short Introductions books was difficult enough, but I think that this challenge was even harder. I was very impressed with the quality and variety of videos which were submitted.

“Ranging from artistic to zany, I learned a lot, and had lots of fun watching them. The longlist represents both a wide range of subjects — from the history of film to quantum locking — and a huge range in the approaches taken to get the subjects across in just one minute.”

We hope the entrants enjoyed thinking about and creating their films as much as we enjoyed watching them. We asked a few of the longlisted students what they made of the experience. Mahshad Torkan, studying at the London School of Film, tackled the political power of film: “I am very thankful for this amazing opportunity that has allowed me to reflect my values and beliefs and share my dreams with other people. I believe that the future is not something we enter, the future is something we create.”

Maia Krall Fry is reading geology at St Andrews: “It seemed highly important to discuss a topic that has really captured my curiosity and sense of adventure. I strongly believe that knowledge of the history of the earth should be accessible to everyone.”

Matt Burnett, who is studying for an MSc in biological and bioprocess engineering at Sheffield, used his film to explore the challenges of creating cost-effective therapeutic drugs: “I felt that in a minute it would be very hard to explain my research in enough detail just using speech, and it would be difficult to demonstrate or act out. I simplify difficult concepts for myself by drawing diagrams, often spending a lot of time on them. For me it is the most enjoyable part of learning, and so I thought it would be fun to draw an animated video. If I get the chance to do it again I think I’d use lots of colours.”

So, what are you waiting for? Take a look at the 12 films and pick your favourite of these amazingly creative and intelligent entries.

Chloe Foster is from the Very Short Introductions team at Oxford University Press. This article originally appeared on guardian.co.uk.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only VSI articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

The post A Very Short Film competition appeared first on OUPblog.

By: ChloeF,

on 1/25/2013

Blog:

OUPblog

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

History,

UK,

tradition,

art,

historical,

Military,

glasgow,

VSI,

Europe,

very short Introductions,

european,

Duke of Wellington,

wellington,

*Featured,

Art & Architecture,

Napoleonic Wars,

VSIs,

Carlo Marochetti,

Gallery of Modern Art,

Glaswegian,

Iron Duke,

Mike Rapport,

traffic cone,

napoleonic,

marochetti,

glasgow’s,

Add a tag

By Mike Rapport

The Duke of Wellington always has a traffic cone on his head. At least, he does when he is in Glasgow. Let me explain: outside the city’s Gallery of Modern Art on Queen Street, there is an equestrian statue of the celebrated general of the Napoleonic Wars. It was sculpted in 1840-4 by the Franco-Italian artist, Carlo Marochetti (1805-1867), who in his day was a dominant figure in the world of commemorative sculpture. Amongst his works is the statue of Richard the Lionheart, who has sat on his mount and held aloft his sword outside the Houses of Parliament since 1860.

Yet Glasgow’s lofty monument has been a magnet for pranksters – ever since the 1980s, according to the BBC – who regularly scale the pedestal, Copenhagen’s (the horse’s) flanks and then, clinging onto the Iron Duke himself, crown him with an orange traffic cone. This has caused some controversy: the police warn that the acts of intrepid, late-night climbers (who, to be frank, may also have enjoyed the hospitality of the local hostelries) is an act of vandalism and is downright dangerous. The government-funded agency that oversees the care of the country’s historic buildings, Historic Scotland, acknowledges that embellishing Wellington with a modern piece of traffic paraphernalia is now a ‘longstanding tradition’, but emphasises that the statue is A-listed and so needs to be protected from damage – and there has indeed been damage: on different occasions, the general has lost a spur and his sword. Others argue that the ‘coning’ of Wellington is a worthy expression of the people’s sense of humour and that it is as much a part of the cityscape as its historic buildings and monuments. And indeed the statue has become iconic – not because it is a likeness of the Duke of Wellington, but because the general has a cone on his head: postcards proudly depicting this symbol of Glaswegian humour are easy to find.

This controversy sprang to mind when I was first putting together a proposal for writing a Very Short Introduction on the Napoleonic Wars. One of the reviewers very helpfully suggested that the book might consider a chapter on the conflict in historical memory and commemoration. When I came to write this, the final chapter, I considered opening it with an account of the ‘coning’ of the Duke of Wellington, but in the end I felt that such irreverence and jocularity sat rather uneasily with the content of the rest of the book, which tells a tale of aggression, international collapse, and human suffering. Yet the fact that the Duke still sits, as ever, with a garish point on his head – gravity making it lean at a jaunty angle – did make me wonder about how far the Napoleonic Wars (including, by extension, the French Revolutionary Wars from which they emerged – collectively the wars lasted from 1792 to 1815) have left a legacy that is embedded, visibly or otherwise, in our European cityscapes.

This might well be more obvious on the continent than in the British Isles, since there was a direct impact as armies rampaged across Europe – and there were therefore more sites clearly associated with Napoleonic conquest, European resistance to it, and later commemoration of the conflict. In Paris, the very same Marochetti was responsible for one of the reliefs on the Arc de Triomphe in Paris, the one depicting the Battle of Jemappes (one of the French Revolution’s early victories over the Austrians in 1792). The Arc was completed under the July Monarchy (1830-48), which worked hard to appropriate the Napoleonic legacy for its own political purposes. The same regime nearly awarded Marochetti the commission to create Napoleon’s tomb in the Church of the Invalides when his body was repatriated from Saint Helena. The sculptor, in fact, was producing models for this work as he was busy on Glasgow’s Wellington statue (giving the latter a pedigree that surely reinforces Historic Scotland’s mild-mannered point). Yet British towns and cities are also embedded with places that are connected with the French Wars – as barracks, as headquarters, as places of exile and refuge, as naval dockyards, as depots for PoWs, as sites of popular mobilization. Sometimes the associations are long-forgotten, sometimes they are commemorated. The conflict is remembered in the monuments that ask us not to forget the carnage and in the individuals who are commemorated in stone and bronze. These may, like Glasgow’s Iron Duke, have become so much part of our urban environment that they are almost unnoticed unless they have a cone on their head, but the traces and memory of the French Wars in Britain’s towns and cities… now there’s a project!

Dr Mike Rapport is Senior Lecturer in the Department of History at the University of Stirling. He is the author of Nationality and Citizenship in Revolutionary France: The Treatment of Foreigners 1789-1799 (OUP, 2000), The Shape of the World: Britain, France and the Struggle for Empire (Atlantic, 2006), 1848, Year of Revolution (Little, Brown, 2008), and The Napoleonic Wars: A Very Short Introduction (OUP, 2013).

The Very Short Introductions (VSI) series combines a small format with authoritative analysis and big ideas for hundreds of topic areas. Written by our expert authors, these books can change the way you think about the things that interest you and are the perfect introduction to subjects you previously knew nothing about. Grow your knowledge with OUPblog and the VSI series every Friday!

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only VSI articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only history articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Image credit: Statue of Wellington, mounted. Outside the Gallery of Modern Art, Queen Street, Glasgow, Scotland [Author: Green Lane, Creative Commons Licence via Wikimedia Commons]

The post The legacy of the Napoleonic Wars appeared first on OUPblog.

By: ChloeF,

on 12/28/2012

Blog:

OUPblog

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

Poetry,

Literature,

environment,

poem,

popular culture,

VSI,

very short Introductions,

William Wordsworth,

Sierra Club,

Humanities,

romanticism,

*Featured,

Environmental & Life Sciences,

environmental movement,

VSIs,

Oxford Index,

Michael Ferber,

modern science,

Nationa Trust,

Romantics,

transcendentalist,

perry–castañeda,

Add a tag

By Michael Ferber

William Wordsworth

The Very Short Introductions are indeed very short, so I had to cut a chapter out of my volume that would have discussed the aftermath or legacy of Romanticism today, two hundred years after Romanticism’s days of glory. In that chapter I would have pointed out the obvious fact that those who still love poetry look at the Romantic era as poetry’s high point in every European country. Think of Wordsworth, Keats, Shelley, Pushkin, Mickiewicz, Leopardi, Lamartine, Hugo, and Nerval. Those who still love “classical” music fill the concert halls to listen to Beethoven, Schumann, Chopin, Berlioz, and Wagner; and those who still love traditional painting flock to look at Constable, Turner, Friedrich, and Delacroix. These poets and artists are still “alive”: their works are central to the culture from which millions of people still draw nourishment. I can scarcely imagine how miserable I would feel if I knew I could never again listen to Beethoven or read a poem by Keats.

But more interesting, I think, is the afterlife of the Romantics in more popular culture. Take William Blake, for instance. Almost a century after he died, Charles Parry set Blake’s sixteen-line poem “And did those feet in ancient time / Walk upon England’s mountains green” to a memorable hymn tune. It was first intended for a patriotic rally during World War I, but it was soon taken up by the women’s suffrage movement and the labour movement because of its moving evocation of a once and future Jerusalem in “England’s green and pleasant land.” It is now England’s second national anthem, and is sung in America too: a Connecticut friend of mine always sings “in New England’s green and pleasant land.” It also inspired the title and the music of the 1981 movie Chariots of Fire. Emerson, Lake and Palmer have recorded an acid-rock version of the hymn in Brain Salad Surgery (1973) and Billy Bragg made a more restrained but eloquent one in 1990. In 1948 William Blake “appeared” to Allen Ginsberg in a hallucination, and thus takes much of the credit (or blame) for the Beat poet’s immense poetic works. I often see Blake’s “Proverbs of Hell” as grafitti on walls or as slogans on bumper stickers. When I was an underpaid teaching assistant I joined a picket line carrying a sign I had made: “The tygers of wrath are wiser than the horses of instruction.” Even as a well-broken-in horse of instruction today I still see much truth in that proverb.

A major legacy of Romanticism is the environmental movement. John Muir (1838-1914), the great pioneer of the wilderness preservation movement, and founder of the Sierra Club, combined a Romantic sensibility with an outlook based on the Bible. He absorbed Burns from his native Scotland, Wordsworth, Coleridge, and Shelley from England, and Emerson and Thoreau from his adopted America. Thoreau himself, who was close to the Transcendentalist group, which grew in large part out of German and British Romanticism, was the first great nature writer in America; his Walden is still required reading not only in universities but among those who are devoted to conservation and sustainability. Wordsworth himself, of course, deserves some credit for his role in preserving the Lake District; he is sometimes called the grandfather of the National Trust of the UK

It is true that the environmental movement owes much to modern science, and most modern scientists no longer consider Romanticism a useful source of concepts. However it is also true that without something of the Romantic sensibility, especially the feeling of connectedness to nature or rootedness in the earth, it would not be much of a movement. “Organic” metaphors were common among the Romantics, notably the idea that nature is not a mechanism but a living organism and that in an open and imaginative state of mind we can, as Wordsworth put it, “see into the life of things,”. It seems to me that the holistic and ecological outlook owes much to this spirit. Aldo Leopold (1887-1948), famous for his best-selling Sand County Almanac with its “land ethic,” writes of the “biotic community” and the importance of “thinking like a mountain” to understand the complex interrelationships of humans and nature. And what could be more holistic than the “Gaia” theory of James Lovelock (born in 1919), according to which the whole earth acts like one huge organism or ecological unit?

“Romantic” is often a pejorative term, used to dismiss unrealistic, escapist, woolly, or dreamy ideas. But it now seems likely that if we don’t soon become a little more Romantic, the earth will dismiss us.

Michael Ferber is Professor of English and Humanities and English Graduate Director at the University of New Hampshire. He is the author of several books including Romanticism: A Very Short Introduction.

The Very Short Introductions (VSI) series combines a small format with authoritative analysis and big ideas for hundreds of topic areas. Written by our expert authors, these books can change the way you think about the things that interest you and are the perfect introduction to subjects you previously knew nothing about. Grow your knowledge with OUPblog and the VSI series every Friday!

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only VSI articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only literature articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Image Credit: A portrait of William Wordsworth from Portrait Gallery of the Perry–Castañeda Library of the University of Texas at Austin [public domain via Wikimedia Commons]

The post Romanticism: a legacy appeared first on OUPblog.

By: Alice,

on 12/21/2012

Blog:

OUPblog

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

Literature,

On the Road,

VSI,

very short introduction,

jack kerouac,

beat generation,

Allen Ginsberg,

Humanities,

*Featured,

TV & Film,

Arts & Leisure,

Walter Salles,

VSIs,

David Sterritt,

Jose Rivera,

the beats,

William S. Burroughs,

kerouac,

Add a tag

By David Sterritt

Jack Kerouac, the novelist and poet who gave the Beat Generation its name, died 43 years ago on 21 October 1969 at the age of 47. This Friday, the long-delayed movie version of Kerouac’s autobiographical novel about crisscrossing the United States with his hipster friend Neal Cassady in the 1940s, On the Road releases. When the novel was published in 1957, six years after he finished writing it, Kerouac dreamed up his own screen adaptation, hoping to play himself (called Sal Paradise in the novel) opposite Marlon Brando as Dean Moriarty, the Cassady character. He wrote to Brando but Brando didn’t write back, so the dream production remained a dream. Now that it’s reaching the screen with Sam Riley and Garrett Hedlund as Sal and Dean, we can only guess what Kerouac would have made of it.

On the Road remains Kerouac’s most widely acclaimed novel, partly for its literary merits — boundless energy, quicksilver prose, an almost mystical view of the American landscape — and partly because of the legendary way he created it, typing it on a 120-foot scroll so he wouldn’t have to interrupt the flow of words by changing paper. Kerouac wrote many other works, including several novels, a great deal of poetry, two books about Buddhism, a compendium of his nightly dreams, and a play that inspired the 1959 movie Pull My Daisy, a mostly playful glance at the mercurial Beat lifestyle. But his most prolific period was limited to the 1950s, when he wrote nearly of his significant works.

Weighed down and ultimately defeated by alcoholism and depression, Kerouac produced little of note after 1960 except the novels Big Sur and Vanity of Duluoz: An Adventurous Education, 1935-46, published in 1962 and 1968 respectively. He felt badly misunderstood by the American public, and although he was right, he was also to blame. His footloose characters and propulsive writing style had convinced admirers and detractors alike that being Beat meant disdaining the ordinary social rules — which was true as far as it went, but far less important to Kerouac than the need to be both “beat” and “beatific,” meaning saintly in a literal sense. Appearing on William F. Buckley Jr.’s conservative TV show a year before his death, Kerouac said he rejected the “mutiny” and “insurrection” that the Beats had come to connote; instead he favored “order, tenderness and piety.” By this time, however, the Beats had given way to the flower children as the American gadflies par excellence, and few were interested in the profoundly religious sensibility — oscillating between Catholicism and Buddhism but always deeply felt — of a once-blazing rebel now seen as a soggy old complainer.

Sam Riley and Garrett Hedlund in On the Road. Photo © Gregory Smith. Source: ontheroad-themovie.com

Although the original Beats were a loosely knit crew, its key members were unquestionably Kerouac, fiercely committed to the spontaneous writing he pioneered; Allen Ginsberg, a modernist poet inspired by everything from 19th-century verse to late-night radio patter; and William S. Burroughs, a storyteller with a schizoid style and a hearty appetite for sex, drugs, and metaphysics. Their rebellious values have stayed in the social imagination ever since their early days as friends and fellow travelers, influencing the cyberpunks of the 2000s no less than the hippies of the 60s and the punks of the 70s.

Two ideas united them: a shared rejection of consumerism and regimentation, and a collective desire to purge their lives of spiritually deadening dross. Their rallying cry was a call for remaking consciousness on a deeply inward-looking basis — revitalizing society by revolutionizing thought, rather than the other way around, through cultivation of “the unspeakable visions of the individual,” in Kerouac’s unforgettable phrase. They had different ways of accomplishing this. Kerouac became a self-described “great rememberer redeeming life from darkness” in the many novels he wrote; Ginsberg invented a new variety of incantatory, almost shamanistic verse; Burroughs cut, folded, and shuffled his pages to bypass his ego and extract fresh, outlandish truths. The ultimate goal for them and their followers is what Kerouac called “eyeball kicks,” the jolts of cosmic energy that divide everyday diversions from visionary art.

The new movie version of On the Road was written by Jose Rivera and directed by the respected Brazilian filmmaker Walter Salles, who deserves an Oscar for just getting the picture finished. A number of writers, including major ones like Russell Banks and Michael Herr, have tried and failed to complete satisfactory screenplays during the 33 years that producer Francis Ford Coppola has owned the adaptation rights. Rivera’s effort finally captured the tone that Coppola was looking for, and Salles allowed the actors to improvise at times, which is very much in the Beat spirit. Reviews were mixed when the picture premiered at the Cannes International Film Festival last spring, but its American distributors, IFC Films and Sundance Selects, have expressed their optimism by scheduling its theatrical debut for December 21st, a popular timeslot for films with award possibilities. Kerouac loved movies, and one hopes he would have smiled on this big-screen reincarnation of his profoundly personal tale.

David Sterritt is a film professor at Columbia University and the Maryland Institute College of Art, and professor emeritus at Long Island University. A noted critic, author, and scholar, he is chair of the National Society of Film Critics and chief book critic of Film Quarterly, and was for many years the film critic for The Christian Science Monitor. His books include The Beats: A Very Short Introduction, Mad to Be Saved: The Beats, the ’50s, and Film and Screening the Beats: Media Culture and the Beat Sensibility, and he serves on the editorial board of the Journal of Beat Studies. His writings have appeared in the New York Times, Huffington Post, Journal of American History, Journal of Aesthetics and Art Criticism, Beliefnet, Chronicle of Higher Education, and many other publications. Sterritt has appeared as a guest on CBS Morning News, Nightline, Charlie Rose, CNN Live Today, Countdown with Keith Olbermann and The O’Reilly Factor, among many other television and radio shows.

The Very Short Introductions (VSI) series combines a small format with authoritative analysis and big ideas for hundreds of topic areas. Written by our expert authors, these books can change the way you think about the things that interest you and are the perfect introduction to subjects you previously knew nothing about. Grow your knowledge with OUPblog and the VSI series every Friday!

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only film and television articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only literature articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only VSI articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Image credit: Sam Riley and Garrett Hedlund in On the Road. Photo © Gregory Smith. Source: ontheroad-themovie.com. Used for the purposes of illustration.

The post Jack Kerouac: On and Off the Road appeared first on OUPblog.

By: ChloeF,

on 12/14/2012

Blog:

OUPblog

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

photo,

Sociology,

images,

image,

Current Affairs,

controversy,

death,

Media,

government,

protest,

circulation,

photograph,

dying,

VSI,

demonstration,

conspiracy,

very short Introductions,

caption,

Iran,

martyrdom,

reprint,

neda,

demonstrations,

mistake,

hate mail,

*Featured,

martyrs,

Law & Politics,

Tehran,

VSIs,

inaccuracy,

Jolyon Mitchell,

martyr,

Neda Agha-Soltan,

agha,

soltani,

soltan,

protestor,

Add a tag

Jolyon Mitchell

A protestor holds a picture of a blood spattered Neda Agha-Soltan and another of a woman, Neda Soltani, who was widely misidentified as Neda Agha-Soltan.

It was agonizing, just a few weeks before publication of Martyrdom: A Very Short Introduction, to discover that there was a minor mistake in one of the captions. Especially frustrating, as it was too late to make the necessary correction to the first print run, though it will be repaired when the book is reprinted. New research had revealed the original mistake. The inaccuracy we had been given had circulated the web and had been published by numerous press agencies and journalists too. What precisely was wrong?

To answer this question it is necessary to go back to Iran. During one of the demonstrations in Tehran following the contested re-election of President Ahmadinejad in 2009, a young woman (Neda Agha-Soltan) stepped out of the car for some fresh air. A few moments later she was shot. As she lay on the ground dying her last moments were captured on film. These graphic pictures were then posted online. Within a few days these images had gone global. Soon demonstrators were using her blood-spattered face on posters protesting against the Iranian regime. Even though she had not intended to be a martyr, her death was turned into a martyrdom in Iran and around the world.

Many reports also placed another photo, purportedly of her looking healthy and flourishing, alongside the one of her bloodied face. It turns out that this was not actually her face but an image taken from the Facebook page of another Iranian with a similar name, Neda Soltani. This woman is still alive, but being incorrectly identified as the martyr has radically changed her life. She later described on BBC World Service (Outlook, 2 October 2012) and on BBC Radio 4 (Woman’s Hour, 22 October 2012) how she received hate mail and pressure from the Iranian Ministry of Intelligence to support the claim that the other Neda was never killed. The visual error made it almost impossible for Soltani to stay in her home country. She fled Iran and was recently granted asylum in Germany. Neda Soltani has even written a book, entitled My Stolen Face, about her experience of being mistaken for a martyr.

The caption should therefore read something like: ‘A protestor holds a picture of a blood spattered Neda Agha-Soltan and another of a woman, Neda Soltani, who was widely misidentified as Neda Agha-Soltan.’ This mistake underlines how significant the role is of those who are left behind after a death. Martyrs are made. They are rarely, if ever, born. Communities remember, preserve, and elaborate upon fatal stories, sometimes turning them into martyrdoms. Neda’s actual death was commonly contested. Some members of the Iranian government described it as the result of a foreign conspiracy, while many others saw her as an innocent martyr. For these protestors she represents the tip of an iceberg of individuals who have recently lost their lives, their freedom, or their relatives in Iran. As such her death became the symbol of a wider protest movement.

This was also the case in several North African countries during the so-called Arab Spring. In Tunisia, in Algeria, and in Egypt the death of an individual was put to use soon after their passing. This is by no means a new phenomenon. Ancient, medieval, and early modern martyrdom stories are still retold, even if they were not captured on film. Tales of martyrdom have been regularly reiterated and amplified through a wide range of media. Woodcuts of martyrdoms from the sixteenth century, gruesome paintings from the seventeenth or eighteenth centuries, photographs of executions from the nineteenth century, and fictional or documentary films from the twentieth century all contribute to the making of martyrs. Inevitably, martyrdom stories are elaborated upon. Like a shipwreck at the bottom of the ocean, they collect barnacles of additional detail. These details may be rooted in history,unintentional mistakes, or simply fictional leaps of the imagination. There is an ongoing debate, for example, around Neda’s life and death. Was she a protestor? How old was she when she died? Who killed her? Was she a martyr?

Martyrdoms commonly attract controversy. One person’s ‘martyr’ is another person’s ‘accidental death’ or ‘suicide bomber’ or ‘terrorist’. One community’s ‘heroic saint’ who died a martyr’s death is another’s ‘pseudo-martyr’ who wasted their life for a false set of beliefs. Martyrs can become the subject of political debate as well as religious devotion. The remains of a well-known martyr can be viewed as holy or in some way sacred. At least one Russian czar, two English kings, and a French monarch have all been described after their death as martyrs.

Neda was neither royalty nor politician. She had a relatively ordinary life, but an extraordinary death. Neda is like so many other individuals who are turned into martyrs: it is by their demise that they are often remembered. In this way even the most ordinary individual can become a martyr to the living after their deaths. Preserving their memory becomes a communal practice, taking place on canvas, in stone, and most recently online. Interpretations, elaborations, and mistakes commonly cluster around martyrdom narratives. These memories can be used both to incite violence and to promote peace. How martyrs are made, remembered, and then used remains the responsibility of the living.

Jolyon Mitchell is Professor of Communications, Arts and Religion, Director of the Centre for Theology and Public Issues (CTPI) and Deputy Director of the Institute for the Advanced Study in the Humanities (IASH) at the University of Edinburgh. He is author and editor of a wide range of books including most recently: Promoting Peace, Inciting Violence: The Role of Religion and Media (2012); and Martyrdom: A Very Short Introduction (2012).

The Very Short Introductions (VSI) series combines a small format with authoritative analysis and big ideas for hundreds of topic areas. Written by our expert authors, these books can change the way you think about the things that interest you and are the perfect introduction to subjects you previously knew nothing about. Grow your knowledge with OUPblog and the VSI series every Friday!

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only VSI articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only articles on law and politics on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Image credit: A protestor holds a picture of a blood spattered Neda Agha-Soltan and another of a woman, Neda Soltani, who was widely misidentified as Neda Agha-Soltan, used in full page context of p.49, Martyrdom: A Very Short Introduction, by Jolyon Mitchell. Image courtesy of Getty Images.

The post Making and mistaking martyrs appeared first on OUPblog.

By: AlanaP,

on 12/7/2012

Blog:

OUPblog

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

science fiction,

Literature,

Geography,

mars,

VSI,

Seed,

very short Introductions,

wells,

place of the year,

Humanities,

Atlas of the World,

POTY,

War of the Worlds,

Social Sciences,

*Featured,

VSIs,

david seed,

Add a tag

By David Seed

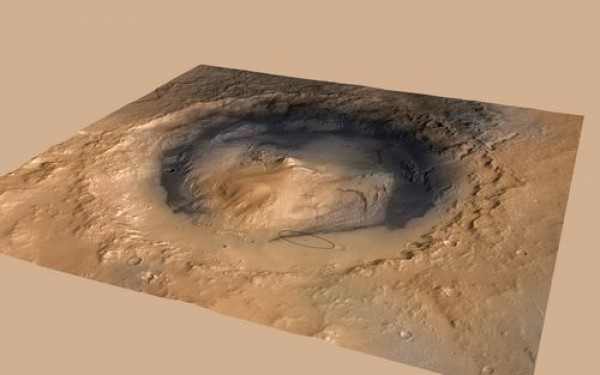

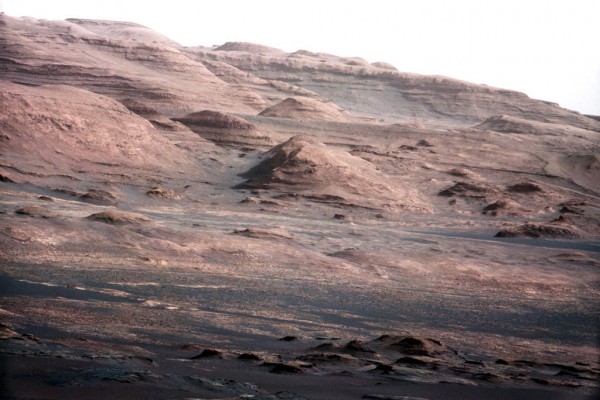

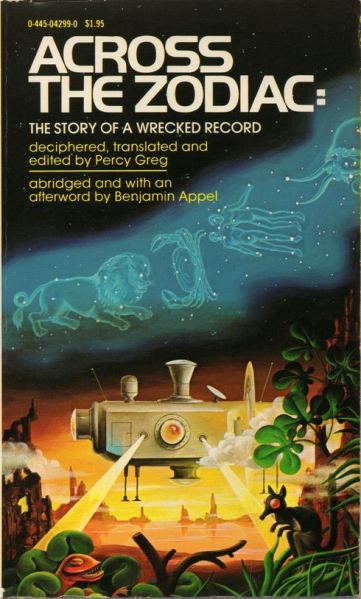

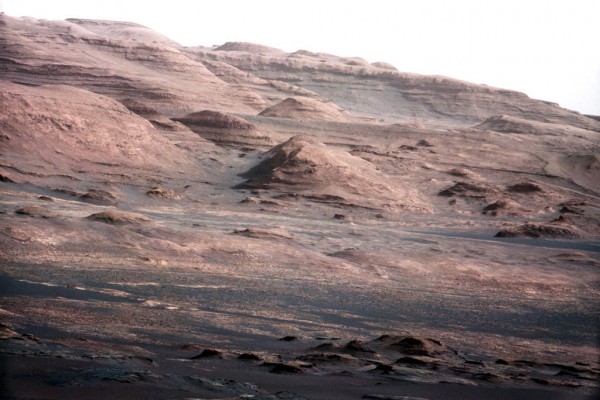

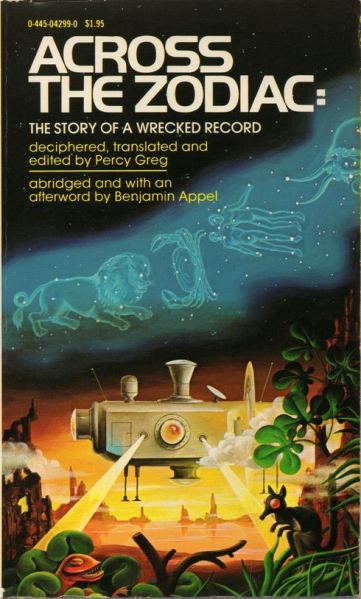

Although there had been interest in Mars earlier, towards the end of the nineteenth century there was a sudden surge of novels describing travel to the red planet. One of the earliest was Percy Greg’s Across the Zodiac (1880) which set the pattern for early Mars fiction by framing its story as a manuscript found in a battered metal container. Greg obviously assumed that his readers would find the story incredible and sets up the discovery of the ‘record’, as he calls it, by a traveler to the USA to distance himself from the extraordinary events within the novel. The space traveler is an amateur scientist who has stumbled across a force in Nature he calls ‘apergy’ which conveniently makes it possible for him to travel to Mars in his spaceship. When he arrives there, he discovers that the planet is inhabited. Since then, the conviction that beings like ourselves live on Mars has constantly fed writings about the planet. The American astronomer Percival Lowell was one of the strongest advocates of the idea in his 1908 book Mars as the Abode of Life and in other pieces, some of which were read by the young H.G. Wells. Mars had the obvious attraction of opening up new sensational subjects. Greg’s astronaut modestly describes his story as the ‘most stupendous adventure’ in human history. It also resembled a colony.

Although there had been interest in Mars earlier, towards the end of the nineteenth century there was a sudden surge of novels describing travel to the red planet. One of the earliest was Percy Greg’s Across the Zodiac (1880) which set the pattern for early Mars fiction by framing its story as a manuscript found in a battered metal container. Greg obviously assumed that his readers would find the story incredible and sets up the discovery of the ‘record’, as he calls it, by a traveler to the USA to distance himself from the extraordinary events within the novel. The space traveler is an amateur scientist who has stumbled across a force in Nature he calls ‘apergy’ which conveniently makes it possible for him to travel to Mars in his spaceship. When he arrives there, he discovers that the planet is inhabited. Since then, the conviction that beings like ourselves live on Mars has constantly fed writings about the planet. The American astronomer Percival Lowell was one of the strongest advocates of the idea in his 1908 book Mars as the Abode of Life and in other pieces, some of which were read by the young H.G. Wells. Mars had the obvious attraction of opening up new sensational subjects. Greg’s astronaut modestly describes his story as the ‘most stupendous adventure’ in human history. It also resembled a colony.

It’s no coincidence that the surge of Mars fiction coincided with the peak of empire, so by this logic the red planet is sometimes imagined as a transposed other country. Gustavus W. Pope’s Journey to Mars (1894) describes the voyage of an American spacecraft to a utopian world of sophisticated civilization and technology. The Martians encountered by the travelers are immediately identified as allies and one of the climactic moments in the novel comes when they fly the American flag during a naval parade. The narrator is almost moved beyond words by the spectacle:

My eyes filled with tears of joy when I thought that, the banner of liberty which waves o’er the land of the free and the home of the brave, honoured in every nation and on every sea of Earth’s broad domain, should have been borne through the trackless realms of space, amid that shining galaxy of orbs that wheel around the sun, and UNFOLD ITS BROAD STRIPES AND BRIGHT STARS OVER ANOTHER WORLD!

Pope’s description is unusual in presenting the Martians as so similar to the travelers that they project hardly any sense of the alien and, even more important, seem quite happy for America to take the lead in the course of civilization.

The most famous Mars novel from the turn of the twentieth century, H.G. Wells’ The War of the Worlds (1898), takes the British treatment of the Tasmanians as a notorious example of brutal imperialism and then simply reverses the terms. The invading Martians simply direct against the capital city of the British Empire the same crude logic of empire: we are technologically able to conquer you, so we will do so. What still gives an impressive force to Wells’ narrative is the journalistic care that he took to document the gradual collapse of England. Despite its army and navy, the state is helpless to resist the Martians and they are only defeated by the germs of Earth rather than by its technology.

The most famous Mars novel from the turn of the twentieth century, H.G. Wells’ The War of the Worlds (1898), takes the British treatment of the Tasmanians as a notorious example of brutal imperialism and then simply reverses the terms. The invading Martians simply direct against the capital city of the British Empire the same crude logic of empire: we are technologically able to conquer you, so we will do so. What still gives an impressive force to Wells’ narrative is the journalistic care that he took to document the gradual collapse of England. Despite its army and navy, the state is helpless to resist the Martians and they are only defeated by the germs of Earth rather than by its technology.

Cover of “Edison’s Conquest of Mars”, from 1898. Illustration by G. Y. Kauffman.

This story of collapse did not please the American astronomer Garrett P. Serviss, who immediately wrote a sequel, Edison’s Conquest of Mars. Rather than waiting passively for the Martians to return, as Wells warns they might in his coda, Serviss describes an expedition to conquer them on their home planet. Two steps have to be taken before this can be done. First, the American inventor Edison discovers the secrets of the Martians’ technology and devises a ‘disintegrator’, which will destroy its targets utterly. Secondly, the nations of the world have to chip in to the expedition with large donations. Serviss describes an amazingly unanimous global cooperation: “The United States naturally took the lead, and their leadership was never for a moment questioned abroad.” Put this narrative against the background of the USA taking over former Spanish colonies like Cuba and the Philippines, and Serviss’s narrative can be read as an idealized fantasy of America’s emerging imperial role in the world. Of course no conquest would be worthwhile if it came too easily and Serviss’s Martians aren’t the octopus-like creatures described by Wells, but instead represent human qualities and characteristics taken to inhuman lengths.

Empire was only one way of imagining Mars. It also offered itself as a hypothetical location for utopian speculation. This is how it functions in the Australian Joseph Fraser’s Melbourne and Mars (1889), whose subtitle — The Mysterious Life on Two Planets — indicates the author’s method of comparison. Similarly, Unveiling a Parallel, by Two Women of the West (1893), written by the Americans Alice Ingenfritz Jones and Ella Merchant, describes two alternative societies visited by a traveler from Earth. All Mars fiction tends to take for granted the technology of flight and the vehicle in this novel is an ‘aeroplane’, one of the earliest uses of the term. When the narrator lands on Mars he has no difficulty at all in adjustment or with the language, quite simply because Mars is not treated as an alien place so much as a forum for social change.

The most surprising characteristic of early Mars writing is its sheer variety. Sometimes the planet is imagined as a potential colony, sometimes as an alternative society, or as place for adventure. One of the strangest versions of the planet was given in the American natural scientist Louis Pope Gratacap’s 1903 book, The Certainty of a Future Life on Mars. The narrator’s father is a scientist researching into electricity and astronomy with a strong commitment to spiritualism. After he dies, the narrator starts receiving telegraphic messages from his father describing Mars as an idealized spiritual haven for the dead. It is typical of the period for Gratacap to combine science with religion in narrative that resembles a novel. Before we dismiss the idea of telegraphy here, it is worth remembering that the electrical experimenter Nikola Tesla published articles around 1900 on exactly this possibility of communicating electronically with Mars and other planets.

All the main early works on Mars are available on the web or have been reprinted. They make up a fascinating body of material which helps to explain where our perceptions of the red planet come from.

David Seed is Professor in the School of English, University of Liverpool. He is the author of Science Fiction: A Very Short Introduction.

The Very Short Introductions (VSI) series combines a small format with authoritative analysis and big ideas for hundreds of topic areas. Written by our expert authors, these books can change the way you think about the things that interest you and are the perfect introduction to subjects you previously knew nothing about. Grow your knowledge with OUPblog and the VSI series every Friday!

Oxford University Press’ annual Place of the Year competition, celebrating geographically interesting and inspiring places, coincides with its publication of Atlas of the World — the only atlas published annually — now in its 19th Edition. The Nineteenth Edition includes new census information, dozens of city maps, gorgeous satellite images of Earth, and a geographical glossary, once again offering exceptional value at a reasonable price. Read previous blog posts in our Place of the Year series.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only literature articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Image credit: War of the Worlds’ 1st edition cover.

The post The discovery of Mars in literature appeared first on OUPblog.

By: ChloeF,

on 12/7/2012

Blog:

OUPblog

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

meta,

Current Affairs,

government,

Power,

market,

organizations,

state,

VSI,

network,

governing,

politicians,

globalization,

very short Introductions,

laws,

institutions,

European Union,

Governance,

rule,

global economy,

*Featured,

Law & Politics,

corporation,

organisations,

VSIs,

Mark Bevir,

meta-governance,

social practices,

“governance”,

schulz,

bevir,

hollowing,

Add a tag

By Mark Bevir

Governance, governance everywhere – why has the word “governance” become so common? One reason is that many people believe that the state no longer matters, or at least the state matters far less than it used to. Even politicians often tell us that the state can’t do much. They say they have no choice about many policies. The global economy compels them to introduce austerity programs. The need for competitiveness requires them to contract-out public services, including some prisons in the US.

If the state isn’t ruling through government institutions, then presumably there is a more diffuse form of governance involving various actors. So, “governance” is a broader term than “state” or “government”. Governance refers to all processes of governing, whether undertaken by a government, market, or network, whether over a family, corporation, or territory, and whether by laws, norms, power, or language. Governance focuses not only on the state and its institutions but also on the creation of rule and order in social practices.

Martin Schulz, President of the European Parliament